Abstract

Our homology molecular model of the open/inactivated state of the Na+ channel pore predicts, based on extensive mutagenesis data, that the local anaesthetic lidocaine docks eccentrically below the selectivity filter, such that physical occlusion is incomplete. Electrostatic field calculations suggest that the drug's positively charged amine produces an electrostatic barrier to permeation. To test the effect of charge at this pore level on permeation in hNaV1.5 we replaced Phe-1759 of domain IVS6, the putative binding site for lidocaine's alkylamino end, with positively and negatively charged residues as well as the neutral cysteine and alanine. These mutations eliminated use-dependent lidocaine block with no effect on tonic/rested state block. Mutant whole cell currents were kinetically similar to wild type (WT). Single channel conductance (γ) was reduced from WT in both F1759K (by 38%) and F1759R (by 18%). The negatively charged mutant F1759E increased γ by 14%, as expected if the charge effect were electrostatic, although F1759D was like WT. None of the charged mutations affected Na+/K+ selectivity. Calculation of difference electrostatic fields in the pore model predicted that lidocaine produced the largest positive electrostatic barrier, followed by lysine and arginine, respectively. Negatively charged glutamate and aspartate both lowered the barrier, with glutamate being more effective. Experimental data were in rank order agreement with the predicted changes in the energy profile. These results demonstrate that permeation rate is sensitive to the inner pore electrostatic field, and they are consistent with creation of an electrostatic barrier to ion permeation by lidocaine's charge.

Local anaesthetic (LA) drugs such as lidocaine interfere with impulse conduction in nerve and muscle by binding to the inner pore of voltage-gated Na+ channels and blocking current (Hille, 2001). The major drug mechanism of action is not resolved, with experimental evidence variously favouring steric block, stabilization of a closed state, or some combination of the two. Extensive site-directed mutagenesis experiments have provided strong evidence that lidocaine-like drugs (LA) bind in the inner pore. S6 segment residues in domains I, III and IV (but not II) have been shown to be important for use-dependent LA block (Ragsdale et al. 1994; Wright et al. 1998; Yarov-Yarovoy et al. 2001; Yarov-Yarovoy et al. 2002). Two residues in domain IV S6 are of particular importance – Phe-1759 (following the heart NaV1.5 isoform numbering, corresponding to Phe-1579 in skeletal NaV1.4 and Phe-1764 in brain NaV1.2) and Tyr-1766 (Tyr-1586 in NaV1.4; Tyr-1771 in NaV1.2), because their alanine mutants exhibit the greatest changes in LA affinity. Open/inactivated state block of the brain isoform NaV1.2 by etidocaine was reduced by 130- and 35-fold for the alanine substitutions of the phenylalanine and tyrosine, respectively (Ragsdale et al. 1994). Cysteine accessibility experiments with methanethiosulphonate (MTS) reagents confirm that these domain IV S6 residues face the pore and are therefore well positioned to interact with LA drugs (Sunami et al. 2004; Dembowski et al. 2006).

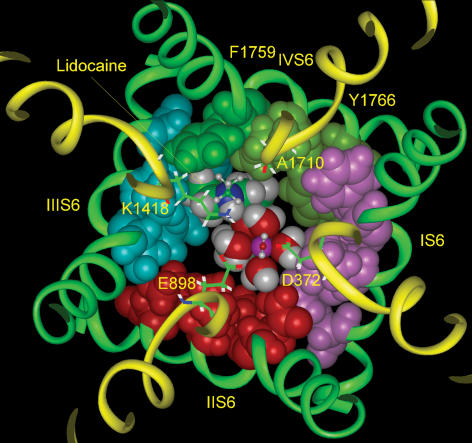

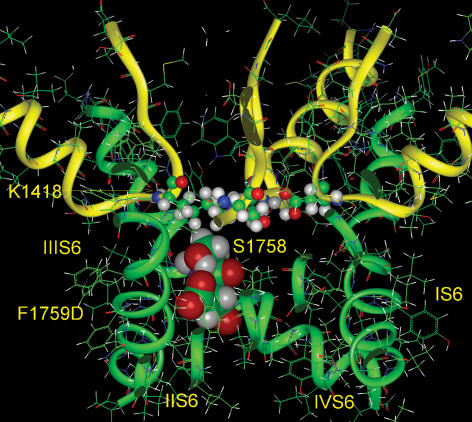

Based on the evidence that LA drugs have a significantly higher affinity for channels in the open/inactivated conformations (Li et al. 1999; Hille, 2001), we recently proposed a molecular model of LA binding in the pore of the open/inactivated Na+ channel. The model used the main chain M2 coordinates of the open MthK channel (Jiang et al. 2002), in combination with an α-helix-turn-β-strand motif for the P-loops (Lipkind & Fozzard, 2000). It incorporated the available mutagenesis information for the LA binding site and compared the docking energies of a series of structurally related LA drugs (Lipkind & Fozzard, 2005). As dictated by mutagenesis data, the alkylamino head of the drug was docked in close association with the phenylalanine of DIV S6 and the drug's aromatic ring docked with the critical tyrosine residue of DIV S6. Lidocaine lies against DIII S6 and DIV S6 and occupies about half of the lumen cross-sectional area at that level, suggesting that the drug may not totally occlude the pore, leaving space for Na+ to pass (Fig. 1). Structurally, LA drugs of the lidocaine class contain a hydrophobic domain and a hydrophilic domain, which includes a tertiary amine that has a pKa between 8 and 9 and is therefore mostly protonated at physiological pH. The model positions the drug's positive charge near the selectivity filter, about 10 Å below the selectivity filter lysine residue in domain III and in an appropriate position to create an electrostatic barrier to Na+ permeation. The calculated electrostatic potential in the channel pore produced by the positive charge on the alkylamine head would be predicted to interrupt sharply the negative electrostatic potential normally generated by the six carboxylates in the Na+ channel's outer vestibule and selectivity filter (Lipkind & Fozzard, 2005).

Figure 1. Lidocaine docked in a model of the Na+ channel pore.

Model coordinates described in Lipkind & Fozzard (2005). Lidocaine docks eccentrically in the open pore of the Na+ channel beneath the DEKA selectivity filter (shown as sticks for clarity and numbered). Lidocaine and the side chains of S6 α-helices facing the inner pore are shown by space-filled images. Domains I, II, III and IV are distinguished by pink, red, blue and green, respectively. The figure also shows a possible location of a hydrated Na+ ion (with octahedral coordination) in its pathway inside the pore between the alkylammonium group of lidocaine and the α-helix of domain II S6. The upper molecule of water and the upper alkyl chain of lidocaine are shown by small balls and sticks for clarity.

The predicted eccentric location of the drug in the channel raises the possibility that LA drugs reduce the pore lumen without completely occluding it and that full interruption of permeation may therefore be achieved by an electrostatic barrier. Electrostatics have recently been shown to play an important role in μ-conotoxin block of NaV1.4, since it does not fully occlude the pore (Chang et al. 1998; Hui et al. 2002). In order to test the electrostatic block hypothesis, we introduced positive and negative charge at position 1759 by replacing phenylalanine with lysine (K), arginine (R), glutamate (E), and aspartate (D), amino acids that would be predicted to alter the electrostatic profile of the channel without creating a steric component. Consistent with electrostatic predictions, mutant channels with positive charges at position 1759 exhibited reduced single channel conductance (γ). Conversely, substitution with the negatively charged glutamate increased γ and aspartate was like WT. None of the charged mutations at 1759 changed the Na+/K+ selectivity ratio. Modelling of the electrostatic field within the channel pore predicted changes in the energy profile that were in the same rank order as the experimental results. We conclude that lidocaine block could result from the combined effect of narrowing of the pore lumen (steric block) and creation of an electrostatic barrier to permeation.

Methods

Site-directed mutagenesis and heterologous expression

The cDNA for the human heart voltage-gated Na+ channel, Nav1.5 (hH1a), was kindly provided by H. Hartmann (University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute, Baltimore, MD, USA) and A. Brown (Chantest Inc., Cleveland, OH, USA) (Hartmann et al. 1994). The background for all mutations was a channel in which the cysteine in the DI, P loop at position 373 was mutated to tyrosine (C373Y). This position controls sensitivity to the guanidinium toxins, tetrodotoxin (TTX) and saxitoxin (STX) (Satin et al. 1992), and is accessible to extracellular MTS reagents that reduce currents (Kirsch et al. 1994). The C373Y mutation exerts minimal effects on channel kinetics (McNulty et al. 2006). Point mutations at 1759 were generated using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA), according the manufacturer's protocols, or a four-primer PCR strategy. Silent restriction enzyme sites were also introduced to allow for identification of positive clones via qualitative restriction enzyme mapping. DNA sequencing was performed to confirm mapping results. The cDNAs were subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA5/FRT and transfected into HEK Flp-In-293 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) cells using the calcium-phosphate, Lipofectamine Plus, or Superfect (Invitrogen) transfection methods. Stable cell lines were created using Hygromycin B (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) or HygroGold (Invivogen, San Diego, CA, USA) selection (100 μg ml−1 for selection, 50 μg ml−1 for maintenance). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin–streptomycin, and selection antibiotic in 60–100 mm Corning (Acton, MA, USA) culture dishes. Whole cell or cell attached voltage clamp was performed on trypsinized cells (0.25% Trypsin-EDTA, Invitrogen) 3–6 days after plating.

Solutions and chemicals

Whole cell voltage clamp was used to measure ionic currents. Channel densities in the various cell lines were too high to allow adequate voltage control of macroscopic ionic currents in physiological (140 mm) extracellular Na+. Therefore, for macroscopic ionic current measurements (excluding the biionic experiments), extracellular Na+ was lowered and replaced with Cs+ in order to keep peak inward currents smaller than 1–3 nA. Bath solution contained (mm): 5–70 NaCl, 135–70 CsCl, 10 Hepes, 2 CaCl2, pH 7.4 with CsOH. A bath to pipette ratio of ∼2: 1 for Na+ concentration was maintained. Pipette solution contained 100 CsF, 10 EGTA, 10 Hepes, and varying concentrations of NaCl and CsCl (summing to 40 mm), depending on the extracellular Na+ concentrations used, pH 7.4 with CsOH. For biionic experiments used to examine the channels' Na+/K+ selectivity, bath solution contained (mm) 140 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 10 Hepes, pH 7.3 with NaOH; pipette solution contained (mm) 100 KF, 40 KCl, 10 Hepes, 10 EGTA, pH 7.3 with KOH. Biionic reversal potentials were also performed using the reverse gradient in which Na+ replaced K+ in the pipette solution and K+ replaced Na+ in the bath.

Single channel measurements were made using the cell attached voltage clamp configuration. Pipette solution contained (mm): 280 NaCl, 10 Hepes, pH 7.4 with NaOH. Bath solution contained (mm): 150 KCl, 10 Hepes, 2 CaCl2, pH 7.4 with KCl. Fenvalerate, a synthetic pyrethroid that stabilizes the open state of Na+ channels (Narahashi, 1985, 1986) without altering single channel conductance (Holloway et al. 1989; Benitah et al. 1997), was added (20 μm) to the pipette solution just before use.

Lidocaine (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in bath solution and applied using either a single chamber bath in which solutions were exchanged using a latching subminiature solenoid valve (The Lee Company, Westbrook, CT, USA) or a multichamber bath in which cells sealed to the patch pipette were lifted and moved from chamber to chamber to measure currents in the absence and presence of drug.

Electrophysiological recordings and analysis

All recordings were made at room temperature (20–25°C) using either the whole cell or cell attached voltage clamp configurations. Patch pipettes for whole cell experiments were pulled from thin-walled borosilicate (World Precision Instruments, Inc, Sarasota, FL, USA) or Fisherbrand microhematocrit (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) glass capillaries using the Flaming/Brown micropipette puller P97 (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA) and had resistances of 0.8–1.3 MΩ when filled with pipette solution. Pipettes for single channel measurements were pulled either from quartz glass using the P2000 laser puller (Sutter Instruments) or from thin-walled borosilicate glass, and then fire-polished with a Narishige (Tokyo, Japan) microforge and coated with SigmaCote (Sigma-Aldrich). Single channel pipettes had resistances of 3–6 MΩ when filled with pipette solution. All recordings were made using an Axopatch 200B feedback amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnydale, CA, USA) with a National Instruments PXI-1002 digital-to-analog converter and LabView 7.0 data acquisition software (National Instruments Corporation, Austin, TX, USA) or with a Digidata 1321 A digital-to-analog converter with pCLAMP 8.2 data acquisition software (Molecular Devices, Sunnydale, CA, USA). Data were filtered at 10 kHz using an 8-pole low pass Bessel filter and sampled at 20 kHz for ionic current measurements and filtered at 5 kHz and sampled at 10 kHz for cell attached patch recordings. Single channel measurements were made using gap-free protocols holding cells at different voltages for > 20 s. Single channel data were analysed using Clampfit 8.2 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) or with locally written programs in MatLab 7.0 (The Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

The details of the voltage protocols for macroscopic ionic current experiments are given in Results and in the figure legends. Na+/K+ selectivity ratios were determined by measuring reversal potentials (Erev) under biionic conditions ([Na+]o: [K+]i or [K+]o: [Na+]i). With Na+ in the bath, reversal potentials were measured by depolarizing cells across a voltage range (+50 to +80 mV in 2 mV increments) near the reversal potential predicted by the Nernst equation. Under these ionic conditions, whole cell currents are not well controlled at potentials far from reversal; therefore, only the small inward and outward currents measured near zero were used to determine Erev and a more positive holding potential (−100 mV) was often used to inactivate a fraction of channels. Under the reverse gradient (with Na+ in the pipette), reversal potentials were measured from tail currents recorded during hyperpolarizations (to −80 through −45 in 1 mV increments) after a brief depolarization (0.5–0.6 ms) to −10 or 0 mV. PK/PNa ratios were determined using the following function:

Ionic current data were capacity-corrected using 8–16 subthreshold responses (voltage steps of 10 or 20 mV) and leak-corrected, based on linear leak resistance calculated at potentials negative to −80 mV or by linear interpolation between the current at the holding potential and 0 mV. Pooled data include only cells with a leak resistance of 500 MΩ or greater for whole cell recordings and 5 GΩ or greater for cell attached patch recordings. Data are reported as means ±s.e.m. Curve fitting and statistical analyses (Student's t test) were performed using MatLab and Origin software (OriginLab Corp, Northampton, MA, USA), and fit parameters are reported as the estimate ± standard error of the estimate. A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Molecular modelling

Modelling was made in the Insight and Discover graphical environment (MSI, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), as previously described (Lipkind & Fozzard, 2000). Calculation of electrostatic potentials inside the Na+ channel pore model used the DelPhi module in Insight II, also as previously described (Khan et al. 2002). The dielectric constants were set to 10 for the protein interior and to 80 for the solvent water. All charges had a value of 1. Electrostatic potentials are given in units of kT/e, where k is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature in kelvins, and e represents the elementary charge. Calculations of volumes of the LA molecules and the space within the inner pore were performed with the Search Compare module.

Results

Mutation of Phe-1759 in NaV1.5 disrupts lidocaine block

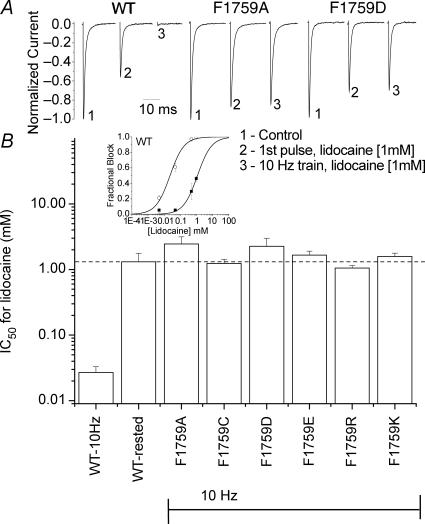

Mutagenesis studies point to the domain IV S6 phenylalanine at 1759 (or equivalent positions in other Na+ channel isoforms) as a critical molecular determinant for local anaesthetic block. An alanine substitution at this position in brain NaV1.2, for example, virtually eliminated use-dependent block by the LA etidocaine (Ragsdale et al. 1994). Similar findings in other isoforms and with other LA drugs have since been reported. We extended these previous findings by examining lidocaine block of NaV1.5 channels in which Phe-1759 was replaced with the positively charged lysine and arginine, the negatively charged aspartate and glutamate, or the neutral alanine and cysteine. Under our experimental conditions, rested state (sometimes called tonic block) was not statistically different between the parent construct and all mutant channels. Use dependent block, as measured with a 10 Hz train of depolarizations, was absent for all mutant channels (Fig. 2). The dose–response relationships were similar for the neutral cysteine and alanine as they were for positively charged mutations, implying that the reduction in block was not simply a result of electrostatic repulsion of the positively charged lidocaine from the inner pore, but rather it was consistent with loss of its binding interaction with phenylalanine.

Figure 2. Lidocaine block of Phe-1759 mutants.

A, representative normalized current traces of WT, F1759A and F1759D channels in the absence and presence of lidocaine. Currents at −10 mV (from Vholding of −140 mV) were first recorded in the absence of lidocaine (1). Lidocaine (1 mm) was then washed on for 3–5 min while cells were held at −140 mV (currents are shown as the fraction of peak current in absence of lidocaine). The decrease in currents elicited with the 1st pulse following the wash (2) reflects block of closed channels by lidocaine. Use-dependent block was assayed as the additional reduction in current in a 10 Hz train (3). To account for the small reduction in current evident in this protocol from the accumulation of inactivated channels in the absence of drug (average for each mutant was < 15%), currents were normalized to the peak steady state current in the 10 Hz train in the absence of drug. WT exhibited large use dependent block; which was entirely absent in the Phe-1759 mutants. B, inset, dose–response curves for WT representing rested state block (▪) and use-dependent block (○) as described in A (n = 3–8 at each concentration). WT channels exhibited a ∼50-fold increase in the apparent affinity when cells were repetitively depolarized. For mutant channels IC50 values after 10 Hz trains were determined by estimating the IC50 from fractional block over the concentration range of 0.1–10 mm lidocaine (IC50= ((1 – fraction blocked) ×[lidocaine]))/fraction blocked) with each cell contributing one estimate. For none of the mutant channels was block significantly different from that of rested state (dashed line). n values: WT, 10 Hz, 18; WT, rested/1st pulse,13; F1759A, 10; F1759C, 4; F1759D, 9; F1759E, 14; F1759R, 5; F1759K, 9.

Mutation of Phe-1759 by positively charged residues

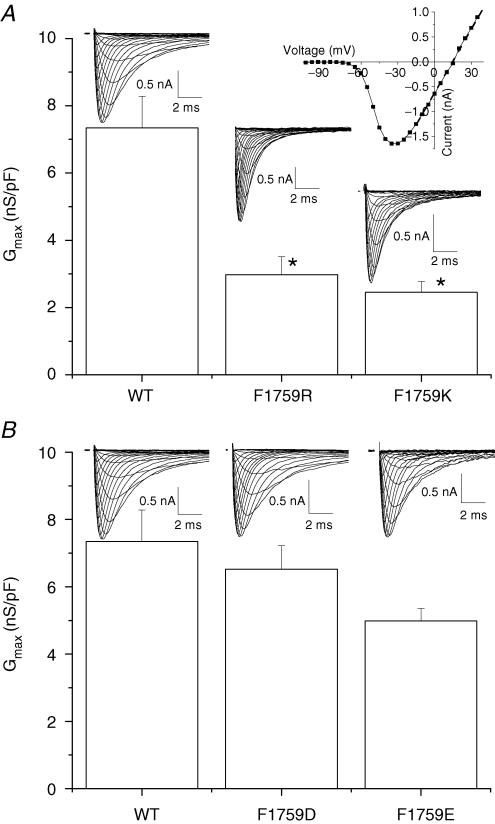

If lidocaine electrostatically interferes with Na+ permeation by virtue of its positive charge lying about 10 Å from the selectivity filter, we should be able to mimic this electrostatic blocking effect of lidocaine by placing a positively charged lysine or arginine at the Phe-1759 position, close to the location of lidocaine's alkylamino group. Consistent with this prediction, mutation of Phe-1759 to either lysine or arginine dramatically reduced maximum macroscopic conductance (Gmax) (Fig. 3A). Macroscopic conductance is a function of the number of channels at the surface, the probability that channels are open, and γ. Since all constructs were stably expressed in HEK Flp-In293 cells, a background in which integration was into a single site, expression levels would not be expected to vary either from day to day as might be the case for transient transfections or because of differences in the characteristics or number of integration site(s). However, differences in channel density could result from differences in folding and trafficking of mutant channels. We therefore directly assessed γ. In order to increase the fidelity of the measurements, channel openings were prolonged with the pyrethroid toxin fenvalerate (20 μm), which has previously been shown not to alter γ (Holloway et al. 1989; Benitah et al. 1997). Substitution of Phe-1759 with lysine or arginine reduced γ 38% (30.5 ± 1.2 pS, n = 4) and 18% (40.6 ± 1.2 pS, n = 4), respectively, compared to WT (49.5 ± 1.1 pS, n = 4) (Fig. 4). The larger changes in Gmax than in γ suggest a change in the probability of being open at the peak of the current or more likely, that there was also a reduction in the number of functional channels in the membrane.

Figure 3. Replacement of Phe-1759 with lysine (K) or arginine (R) reduces macroscopic conductance.

A, currents were recorded using whole cell voltage clamp from a holding potential of −140 mV, stepping from −130 mV to +50 mV every 1–2 s. Maximum macroscopic conductances (Gmax) of individual cells were determined from the slope of the linear region of the current–voltage (I–V) relationships of individual cells and normalized to cell capacitance. Currents through F1759R and F1759K channels were recorded with the following Na+ gradient: 70 mm[Na+]o to 40 [Na+]i. WT currents were measured with 10 mm[Na+]o and 5 mm[Na+]i. All Gmax values were adjusted to the 70/40 Na+ condition. Population data demonstrate that substitution of Phe-1759 with the positively charged residues, lysine or arginine, significantly reduced macroscopic conductance (*P < 0.05). B, maximum macroscopic conductances (Gmax) of channels with replacement of Phe 1759 with aspartate (D) or glutamate (E). Currents through F1759D were recorded with 20 mm[Na+]o and 10 mm[Na+]i. F1759E currents were measured with 10 mm[Na+]o and 5 mm[Na+]i. and again Gmax values were adjusted to the 70/40 Na+ condition. Gmax values for F1759D and F1759E were not significantly different from WT.

Figure 4. Single channel conductance for WT, F1759K and F1759R.

A, representative single channel currents from cell attached patches of WT, F1759K, and F1759R channels, recorded at −100 mV with 280 mm Na+ and 20 μm fenvalerate in the pipette. XY scale bars: all traces are displayed with the same Y scale bar (2 pA); the X scale bars represent 100 ms for the top traces and 50 ms for the bottom traces. B, left, amplitude histograms for selected segments of traces recorded at −100 mV. Marked, baseline corrected segments were analysed in Clampfit 8.2 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and amplitude histograms generated in Origin (OriginLab Corp, Northampton, MA, USA) were fitted with Gaussian distributions using a nonlinear least squares algorithm. Right, averaged amplitudes across patches (n = 4 patches for each channel type) ±s.e.m. are plotted as a function of voltage. Current amplitudes were measured by either directly measuring events in Clampfit 8.2 or through fitting amplitude histograms in Origin. To obtain single channel conductance values, current–voltage relationships from each patch were individually fitted with a linear function. Conductances were then averaged across patches (n = 4 patches for each channel) and are given ±s.e.m. as follows: WT, 49.5 ± 1.1 pS; F1759R, 40.6 ± 1.2 pS; F1759K, 30.5 ± 1.2 pS. Replacement of Phe with lysine and arginine reduced single channel conductance 38% and 18%, respectively.

Replacement of Phe-1759 by negatively charged residues

If the presence of a positive charge at position 1759 reduced the permeation rate via an electrostatic repulsion mechanism, then we might expect a negative charge at the same position to have the opposite effect. On the other hand, our electrostatic modelling predicts a large region of electronegativity created by six carboxylates in the outer pore and selectivity filter in the WT channel (Lipkind & Fozzard, 2005), and therefore, addition of a single unit of negative charge in an already highly electronegative region may have no measurable effect. We tested whether negative charge at 1759 could influence Na+ permeation by measuring whole cell currents and γ in channels mutated to aspartate (F1759D) or glutamate (F1759E). Macroscopic Gmax values for F1759D and F1759E were not statistically different from the WT value (Fig. 3B). γ of F1759E was 57.7 ± 1.2 pS (n = 3), a 14% increase (Fig. 5). On the other hand, γ of F1759D was 46.2 ± 2.3 pS (n = 4), not different from WT. The opposite effect on γ of adding a negative charge with F1759E suggests that the charge effect was the result of a through-space electrostatic field. γ was not altered with alanine or cysteine mutations (49 ± 5, n = 3 and 47 ± 2, n = 2), demonstrating that simply mutating Phe-1759 and removing the aromatic residue alone did not induce a conformational change in the region near the selectivity filter that reduces the permeation rate, but rather the specific addition of a charge near the selectivity filter directly impacted the permeation of Na+ ions.

Figure 5. Single channel conductance for WT, F1759D and F1759E.

A, representative single channel currents from cell attached patches of WT, F1759D, and F1759E channels, recorded at −100 mV with 280 mm Na+ and 20 μm fenvalerate in the pipette. XY scale bars: all traces are displayed with the same Y scale bar (2 pA); the X scale bars represent 100 ms for top traces, 20 ms for bottom left traces, and 50 ms for the bottom middle (F1759D) and right (F1759E) traces. B, left, amplitude histograms for selected segments of traces recorded at −100 mV. Amplitude histograms, generated as described in Fig. 5, were fitted with Gaussian distributions using a nonlinear least squares algorithm. (Right) Averaged amplitudes across patches (n = 4 patches for each channel type) ±s.e.m. are plotted as a function of voltage. Current amplitudes were measured by either directly measuring events in Clampfit 8.2 or through fitting amplitude histograms in Origin. Current–voltage relationships from each patch were individually fitted with a linear function to determine γ. Conductances were then averaged across patches and are given ±s.e.m. as follows: WT, 49.5 ± 1.1 pS (n = 4 patches); F1759D, 46.2 ± 2.3 pS (n = 4 patches); and F1759E, 57.7 ± 1.2 pS (n = 3 patches). Replacement of phenylalanine with aspartate did not affect γ whereas replacement with glutamate increased γ 14%.

Modelling of electrostatic fields

In order to explore the possible mechanism of effects of charge near the selectivity filter on its function, we used the open channel model of Lipkind & Fozzard (2005), which is an approximation of the molecular geometry in the pore. Lidocaine was located eccentrically inside the inner pore and against the α-helices of domains III and IV S6. Figure 1 illustrates this docking, showing the predicted persistent pathway for hydrated Na+ ions (radius ∼3.5 Å) between the aminoalkyl group of lidocaine and domain II S6. Na+ is shown fully hydrated (surrounded by six molecules of water), although in solution Na+ can be surrounded by fewer (4–6) molecules of water (Zhu & Robinson, 1992). At the level of lidocaine's aromatic end the pathway was eccentric extending along domain I S6. The van der Waals volume of lidocaine is ∼212 Å3, and the residual space of the inner pore measured ∼400 Å3. Consequently, lidocaine did not occlude the pore. This model may even have underestimated the inner pore volume, since it has been reported that lysine substitutions in domain II S6 at an equivalent position to phenylalanine failed to affect bupivacaine block (Wang et al. 2001), suggesting that domain II S6 is farther away from the centre of the pore than the other S6 segments. Other commonly used LA molecules of the lidocaine class are structurally similar and about the same volume (e.g. lidocaine is ∼212 Å3 and mepivacaine is ∼217 Å3). None of these and even the larger bupivacaine (∼261 Å3), which has a butyl substituent at its amine instead of mepivacaine's methyl one, would not in this model interfere with the Na+ pathway because they differ in aliphatic substituents which are in touch with the hydrophobic surfaces of domain III and IV (Lipkind & Fozzard, 2005) and therefore do not affect the pathway for Na+ through the residual volume.

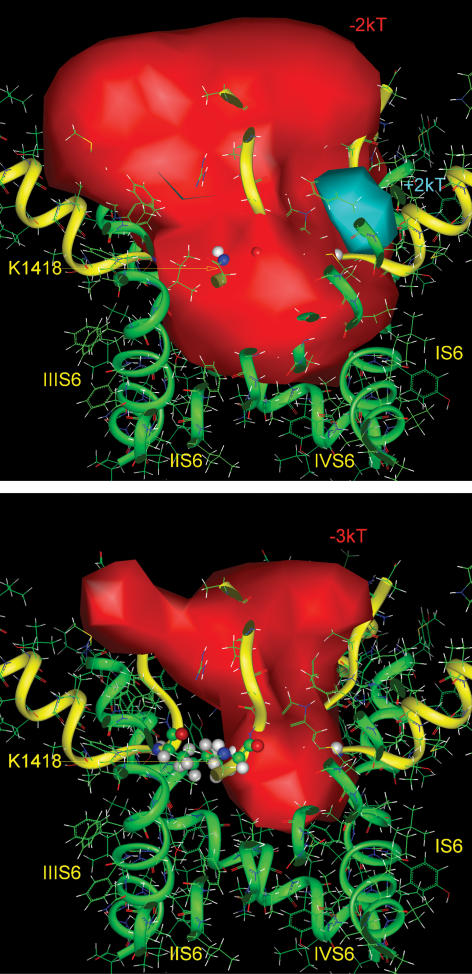

Calculation of the energy of the electrostatic field generated by the negatively charged amino acids in the outer vestibule ring (Glu-375, Glu-891, Asp-1422, and Asp-1713 in NaV1.5) and selectivity ring (Asp-372, Glu-898) demonstrated a strong negative electrostatic field not only in the outer vestibule of the pore, but also extending beneath the selectivity ring (Khan et al. 2002; Lipkind & Fozzard, 2005) (Fig. 6, top), with a strength that was even larger than −3 kT (Fig. 6, bottom). The aminoalkyl charge of lidocaine when bound to Phe-1759, which is predicted to be about as far below the selectivity filter as the external ring of charge is above it, created a positive electrostatic field within the inner pore, which substantially overcame the negative field generated by the carboxylates of the outer vestibule and selectivity ring (Fig. 13 in Lipkind & Fozzard, 2005).

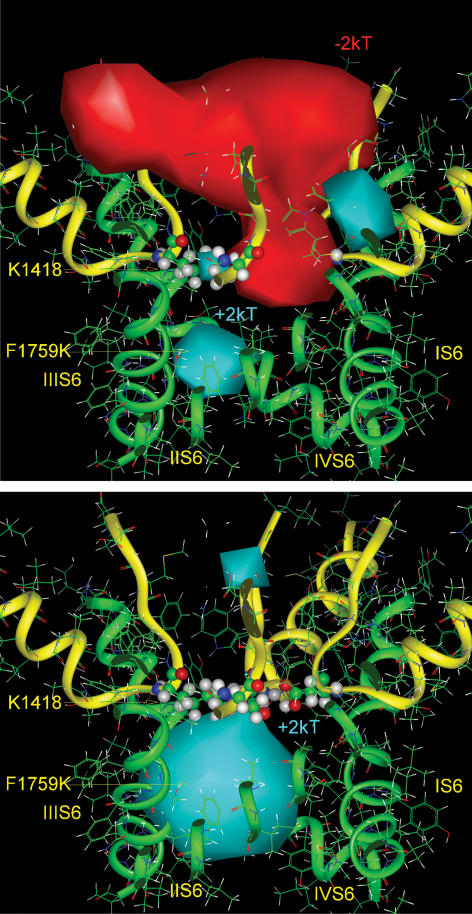

Figure 6. Electrostatic potentials in the pore of the modelled NaV1.5 channel at two energy levels.

Top, the contour of the negative isopotential surface is shown at the level of −2 kT (red solid surface), which fills the volume of both the outer vestibule and the inner pore. Bottom, the contour of the deeper negative isopotential surface is shown at the level of −3 kT which fills the volume of the outer vestibule, through a portion of the selectivity filter. The positive charge of the side chain of lysine (Lys-1418) of the Na+ channel selectivity filter interferes with the negative potential within the proximal region, but the isopotential +3 kT is absent. The channel is shown by side view. The backbones of the pore and the outer vestibule are shown by green and yellow ribbons, respectively. Ball and stick representations are given for the four selectivity filter residues (DEKA motif) of the domains I–IV P loops.

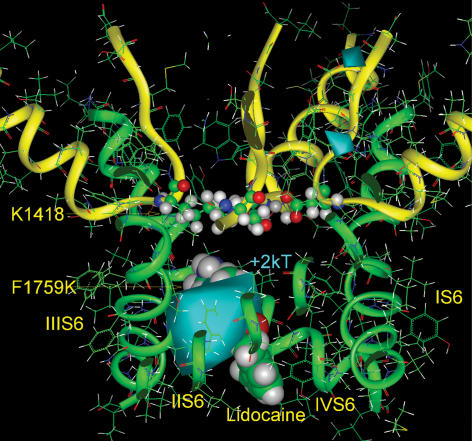

Substitution of lysine (van der Waals volume 120 Å3) or arginine (133 Å3) in the Phe-1759 (125 Å3) position introduced a charge at this level in the pore without impinging on its cross-sectional area, in contrast to the more bulky lidocaine (Fig. 7, top). Similar to lidocaine, the lysine side chain introduced a positive electrostatic potential inside the pore, which also interrupted the negative potential below the selectivity filter. The effect of introducing lysine's charge can be appreciated by calculating the difference electrostatic potential (i.e. subtracting the fields of the mutant F1759K and the WT Na+ channel) (Fig. 7, bottom). The positive electrostatic field was located just below the selectivity filter, where it was in a position to repel Na+ ions and to allow the selectivity filter to function as a trap for Na+ ions. Electrostatic field calculations for F1759R yielded similar results (not shown). The positive fields created by the lysine or arginine substitutions, however, were not the same as that created by the amino group of lidocaine. The alkylamino head and the dimethyl substituted aromatic ring of LAs both partially occlude the inner pore, thereby reducing the amount of nearby water, and interact with the hydrophobic walls of III S6 and IV S6. The combination creates an environment with a relatively low dielectric constant around the LA positive charge, substantially strengthening its positive electrostatic potential. The side chain of Lys-1759, on the other hand, was surrounded by a larger volume of bulk water, which offset its positive field. Lidocaine produced the strongest potential of +5 to +6 kT, compared to the +3 kT of lysine (see also Fig. 11). This is illustrated by the difference electrostatic field between the pore occupied by lidocaine and that of the mutant F1759K (Fig. 8). Consequently, if the electrostatic field of +3 kT created by lysine and arginine substitutions produces block, then the block created by the lidocaine electrostatic field of +5 to +6 kT should be larger by about 3 kT.

Figure 7. Electrostatic potentials in the pore of the F1759K mutant.

Top, the positive charge of the amino head of the side chain of Lys-1759 (presented here by equipotential +2 kT) sharply interrupts the negative electrostatic potential of the outer vestibule (−2 kT, red solid surface) at the level of the selectivity filter (here shown by stick and ball images), hindering Na+ permeation. The channel is shown in side view. The backbones of the pore and the outer vestibule are shown by green and yellow ribbons. Bottom, the difference positive electrostatic potential (+2 kT, blue solid surface) calculated by subtraction of the fields with the F1759K and WT channels, illustrates the field generated only by the side chain of Lys-1759.

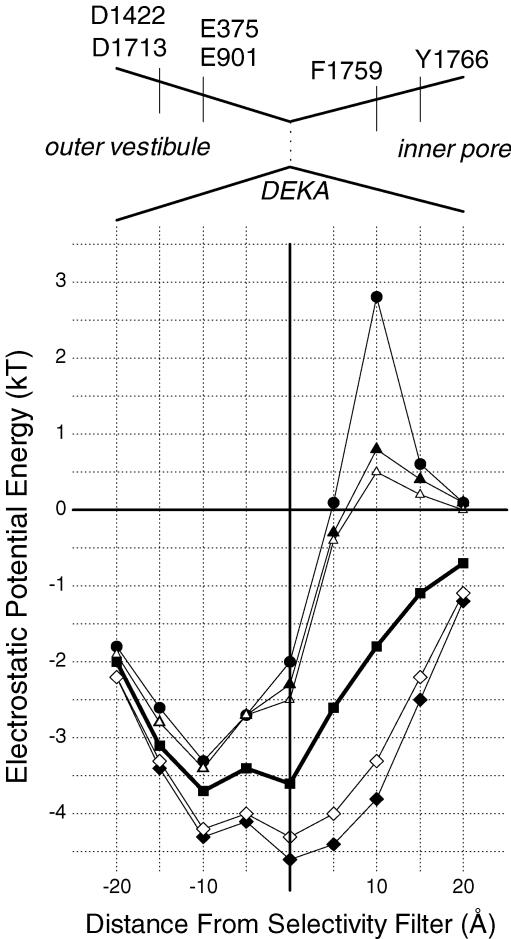

Figure 11. Electrostatic potential energy profiles for Na+ moving along the central axis of the pore for the WT channel (thick line, ▪), for the WT channel with lidocaine bound (•), and channel mutants F1759K (▴), F1759R (▵), F1759E (♦), and F1759D (◊).

Distances are expressed relative to the position of the selectivity filter (DEKA) with the extracellular space to the left (negative values) and the intracellular space to the right (positive values). Diagram above shows a schematic of the pore labelled with location of important amino acid residues.

Figure 8. The difference electrostatic potential between the Na+ channel, blocked by lidocaine, and the F1759K mutant (+2 kT, blue solid surface).

Lidocaine inside of the pore and the side chain of Lys-1759 are shown by space-filled images. The positive electrostatic field introduced by lidocaine is much stronger than that by substitution of Phe-1759 with lysine.

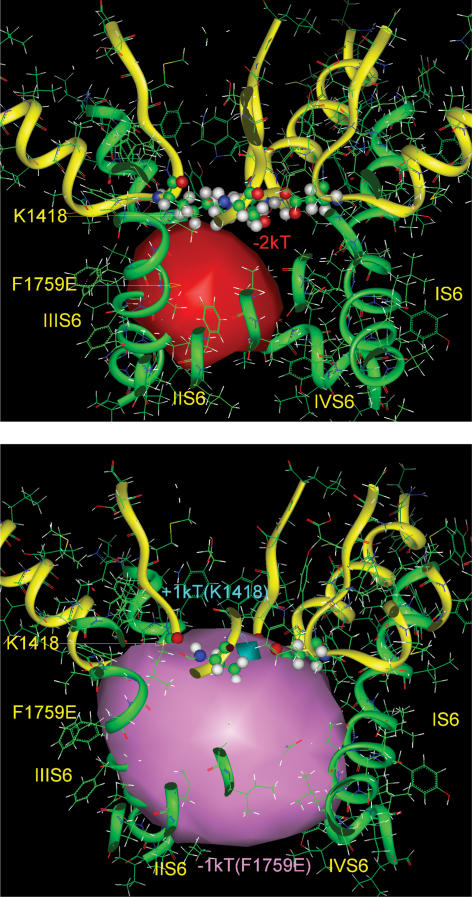

The presence of a negative charge in the model of the mutant channels F1759D and F1759E produced a strengthening of the negative electrostatic field, predicting an enhanced Na+ permeation (Fig. 9, top), which was similar to that predicted and observed with changes in charge in the outer vestibule (Khan et al. 2002). Experimentally, we observed a modest increase in γ for F1759E, while that for F1759D was similar to the WT channel. Interestingly, in the model, the outer vestibule negative electrostatic field, produced largely by the selectivity filter residues Asp-372 and Glu-898, was influenced by the positively charged side chain of Lys-1418 in DIII. The side chain of the amino acid at 1759 was just below the selectivity filter lysine. When glutamic acid was placed at this position, it overcame the weak positive electrostatic potential around Lys-1418, and as a result, it enhanced the negative electrostatic field at the bottom of the outer vestibule (Fig. 9, bottom). Therefore, F1759E was able to produce a modest increase in channel conductance and modulate the negative electrostatic potential of the outer vestibule of the pore. Aspartate has a shorter side chain, and it is also in direct contact with the α-helix backbone. Consequently, the field it generated was projected more into the protein, resulting in a smaller negative field within the pore. In addition, the carboxyl oxygens of aspartate, but not of glutamate, formed a hydrogen bond with the side chain of neighbouring Ser-1758, and its hydroxyl hydrogen screened the negative charge of aspartate (Fig. 10). Either or both of these features could contribute to the lack of effect on γ in the F1759D mutant.

Figure 9. Electrostatic potentials in the pore of the F1759E mutant.

Top, the negative charge of the carboxylate group of the side chain Glu-1759 produced an additional negative electrostatic field inside of the inner pore of the Na+ channel, shown here by the difference negative electrostatic isopotential (−2 kT, red solid surface), calculated by subtraction of the fields with the F1759E and WT Na+ channels. Bottom, the negative electrostatic potential, generated by substitution of Phe-1759 by glutamate (−1 kT, pink solid surface) overcomes the weak positive electrostatic potential produced by Lys-1418 inside of the selectivity filter (+1 kT, blue solid surface) and enhances the negative electrostatic field of the outer vestibule of the Na+ channel.

Figure 10. The mutant F1759D.

The carboxylate group of aspartate at 1759 forms a hydrogen bond with the side chain of neighbouring Ser-1758, screening its negative charge.

An alternative way to illustrate the effect of charge at position 1759 is to calculate the electrostatic potential energy profile for a Na+ ion as it traverses the central axis of the pore (Fig. 11). These values are illustrated according to distance from the selectivity filter plane, which was determined by the DEKA Cα atoms, for WT, the lidocaine-occupied pore, F1759K, F1759R, F1759E and F1759D. The transmembrane electrochemical gradient is not included because its distribution is uncertain. Lidocaine introduced an electrostatic barrier 10 Å below the selectivity filter of about 5 kT, relative to the WT electrostatic potential energy distribution. Positively charged residues at 1759 also raised the barrier, although only about half as much, with lysine being somewhat higher than arginine. Negatively charged residues lowered the barrier with glutamate being more effective than aspartate. When the membrane potential is near zero, then the driving force for Na+ current would be primarily the Na+ chemical gradient, which is typically about −2 kT.

The modelling leads us to favour four ideas: (1) the charges on lidocaine and the Phe-1759 mutations are located in the pore about 10 Å below the selectivity filter lysine, close enough for an electrostatic effect, but not a direct nonbonded interaction; (2) lidocaine reduces the cross-sectional pore area by about half and poses a larger electrostatic barrier to Na+ permeation than the positively charged Phe-1759 mutations by 2–3 kT; (3) the electrostatic effects on the reduction on permeation rate should be lidocaine > F1759K ≥ F1759R; and (4) electrostatic effects on the increase in permeation rate should be F1759E > F1759D. The experimental measurement of change in permeation rate (γ) agreed with this predicted sequence, supporting the idea of a through-space electrostatic field effect.

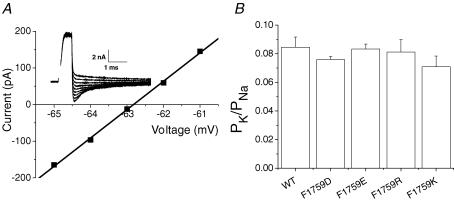

Effect of charged mutations on the Na+/K+ permeability ratio

Selectivity in the Na+ channel is determined mainly by the side chains of the domain II glutamate and the domain III lysine in the DEKA motif (Chiamvimonvat et al. 1996; Favre et al. 1996; Schlief et al. 1996; Tsushima et al. 1997). Because these residues are charged and the side chains are probably flexible, it is plausible that their roles in selectivity might be influenced by the electric field. Indeed, it has been suggested, based on mutagenesis experiments of the outer vestibule and selectivity filter (DEKA) charged residues, that selectivity for Na+ over K+ is achieved by a close interaction that reorients the lysine in the selectivity filter (Favre et al. 1996; Lipkind & Fozzard, 2000). The proximity in the model of the 1759 position to the DIII selectivity filter lysine raised the possibility that the effect of charge on conductance at that site could be secondary to altering the position of the lysine. A particularly sensitive measure of lysine's role in selectivity filter function is the ability to distinguish between Na+ and K+. To test for this possibility we measured reversal potentials for each of the Phe-1759 charged mutants under biionic conditions (140 mm Na+ outside; 140 mm K+ inside or with the reverse gradient) and calculated the PK/PNa permeability ratios. Permeability ratios were not significantly affected by the direction of the gradient or by mutation at Phe-1759 (Fig. 12).

Figure 12. Mutations at Phe-1759 do not alter selectivity.

Na+/K+ selectivity was determined by measuring reversal potentials under biionic conditions (140 mm[Na+]o: 140 mm[K+]i or the reverse gradient, 140 mm[K+]o: 140 mm[Na+]i). With Na+ in the bath and K+ in the pipette, reversal potentials were measured after depolarizing cells from +30 mV to potentials positive to +80 mV at 2 mV increments from a holding potential of −100 mV. With the reverse gradient (140 mm[K+]o: 140 mm[Na+]i), reversal potentials were measured from tail currents recorded during hyperpolarizations (−80 to −45 mV in 1 mV increments) after a brief depolarization (0.5–0.6 s) to −10 mV (A) Representative WT tail currents (inset) and the corresponding current–voltage relationship measured using the reverse gradient (140 mm[K+]o: 140 mm[Na+]i). Two to four data points on either side of the x axis where currents are small and well-controlled were linearly fit to determine the reversal potential. B, permeability ratios (PK/PNa) for Phe-1759 mutants. WT data collected using both gradients yielded the same ratios and were thus pooled. Reversal potentials of the mutant channels were collected under one gradient (140 mm[Na+]o: 140 mm[K+]i). There were no differences in the permeability ratios across Phe-1759 mutants (n values: WT, 12; F1759D, 3; F1759E, 5; F1759R, 3; F1759K, 5).

Discussion

Role of Phe-1759 in LA binding and block

Mutational analyses of Phe-1759 and its equivalent positions in other isoforms have provided strong evidence for its involvement in the binding of local anaesthetics. This phenylalanine was initially proposed as part of the LA binding site in NaV1.2 (Phe-1764) by Ragsdale et al. (1994). They demonstrated that an alanine substitution dramatically reduced use dependent block and further suggested that it was the alkylamino end of the LA molecule that interacted with the phenylalanine. Although suggestive, this result did not prove direct interaction between the phenylalanine and the LA drug. Indeed, evidence has been presented that F1579C (in NaV1.4) did not face the pore lumen (Vedantham & Cannon, 2000). However, Sunami et al. (2004) showed direct interaction between F1579C and inside MTSET, if the channel were kept open long enough for access of the hydrophilic MTS reagent to the site.

Additional mutagenesis data across Na+ channel isoforms also support a direct interaction between this phenylalanine and LA drugs. Mutation of this site in NaV1.3 to serine, alanine, cysteine and isoleucine reduced use-dependent tetracaine block (Li et al. 1999), but mutation to tyrosine or tryptophan preserved tetracaine's effects. In skeletal muscle (NaV1.4), Wright et al. (1998) reported that a lysine mutation at Phe-1579 dramatically reduced block by cocaine, a result that was later confirmed in the cardiac channel (NaV1.5) (Nau et al. 2000) with bupivacaine and in our study here with lidocaine. Similarly, our Cys substitution data are consistent with those of O'Leary & Chahine (2002), in which the same substitution reduced use-dependent cocaine block (O'Leary & Chahine, 2002). Our data demonstrating virtual abolition of use-dependent block by lidocaine with all non-aromatic substitutions at position 1759 further extends the information available for the cardiac isoform. Although direct comparisons between studies are quantitatively limited because of different protocols and drugs used to assay mutational effects, results across data sets are qualitatively consistent, supporting a role of this position in LA binding across isoforms when the channel is in the open/inactivated conformation. These include studies in which the open channel block of permanently charged QX-314 was abolished by the F1579A mutation in NaV1.4 (Kimbrough & Gingrich, 2000), one in which charged flecainide open channel block was abolished by F1759A in NaV1.5 (Liu et al. 2003), as well as previous studies in bilayers with channels isolated from native tissue that implicated the fast mode of block to diethylamide as a surrogate for the charged end of lidocaine (Zamponi & French, 1993). Our molecular model of interaction of the alkylamino end of the LA molecule with Phe-1759 included both van der Waals attraction and electrostatic interaction with the aromatic π electron (Lipkind & Fozzard, 2005). Recently, it was found that LA block was reduced when this phenylalanine was fluorinated (a change that reduces the π electron partial charge) and when an unnatural amino acid with cyclohexane substituted for the aromatic ring (Ahern et al. 2006). It has also been shown that the selectivity filter lysine electrostatically affected LA block and estimated that the alkylamino charge was about 10 Å from this selectivity filter residue (Sunami et al. 1997), the approximately correct distance if LA binds to Phe-1759. In summary, it seems likely that there is indeed a direct interaction between the domain IV S6 phenylalanine and the alkylamino end of the LA molecule.

Effect of charge at position 1759 on permeation

A positive charge in domain IV S6 facing the pore lumen below the selectivity filter reduced whole cell maximal current and γ. Wang et al. (2001) also found that lysine substitution of several domain II S6 residues reduced whole cell currents, although effects on γ were not reported. For the Phe mutants, the reduction in permeation rate accounted for much of the fall in total current, with the remainder probably the result of reduced membrane expression levels of mutant channels.

Although reduction in single channel current secondary to introduction of a positive charge was substantial, it did not recapitulate the complete block produced by lidocaine. Comparison of the calculated electrostatic field effects of lidocaine versus arginine or lysine in our open channel model showed that the lidocaine electrostatic effect would be larger by about 3 kT. The reason for this difference between the positively charged lidocaine and the positively charged mutants is that lidocaine occupies a large space within the open inner pore, reducing the space occupied by water with its higher dielectric constant. From this it is likely that the decrease in γ from the alkylamino positive charge would be significantly larger than we see with mutation of Phe-1759 to lysine or arginine. Lidocaine also partially occluded the pore just below the selectivity filter. The effect of this partial occlusion, independent of any electrostatic block, is not simple to calculate because of the path geometry, but it would be expected to reduce flux by at least half. Lidocaine's electrostatic effect would then be superimposed on this reduction of the cross-sectional area of the pore. This is similar to our study of block in the outer vestibule of the Na+ channel by μ-conotoxin, which occludes about half of the ion pathway but blocks completely because of the positive charge on the side chain of Arg-13 (Chang et al. 1998; Hui et al. 2002).

Introduction of a negative charge by the mutant channel F1759E increased γ, which would be expected if the effect of charge below the selectivity filter were purely electrostatic, although F1759D did not. The reason for this failure is not entirely clear, but the electrostatic energy profile at this position is not predicted to drop below the value at the selectivity filter in WT (Fig. 11). In our model with this mutation introduced, the carboxyl of aspartate is in direct contact with the S6 helix backbone and forms a hydrogen bond with the adjacent Ser-1758, so that its electrostatic field is smaller and is projected more into the protein than into the pore lumen.

When aspartate was introduced into the M2 segment just below the narrow selectivity filter of KIR 3.2, K+ selectivity that had been lost by another mutation was restored (Bichet et al. 2006). In our model the location of the introduced charged residue is just beneath the critical selectivity filter lysine. Several proposals for the mechanism of selective permeation imply that this lysine is displaced when a cation binds to the domain II glutamate, and that the energy of cation displacement of lysine favours Na+ over K+, leading to the selectivity for Na+ (Favre et al. 1996; Lipkind & Fozzard, 2000). Alteration of the electrostatic field around lysine might change the energy required for lysine displacement and thereby would be expected to affect the Na+/K+ selectivity ratio. The failure of our charged mutants to affect this selectivity ratio argues that the electrostatic field does not affect the reaction coordinates between the domain II glutamate, the domain III lysine, and the cation. This is also consistent with the finding that mutation or pH titration of the outer vestibule carboxylates, which alter the electrostatic field in the selectivity filter region, also fail to alter selectivity (Khan et al. 2006).

It must be noted that we used fenvalerate to promote openings and to aid in measuring single channel events. The site of action of fenvalerate is unknown, but modelling based on available mutagenesis data suggests a binding site in a hydrophobic cavity on the intracellular face between domain II and domain III (O'Reilly et al. 2006), not associated with the pore. Two studies report that fenvalerate does not change γ in different Na+ channel isoforms (Holloway et al. 1989; Benitah et al. 1997), and it has previously been used in a mutational study in which a substitution in the outer vestibule was studied (Backx et al. 1992). Because we did not study the channel mutants investigated here in the absence of this agent, we cannot formally exclude the possibility that fenvalerate affected our results, although it seems unlikely since in the presence of fenvalerate several mutations of Phe-1759 did not alter conductance from that of WT, while others decreased it and another increased it.

Assumptions about electrostatic field calculations

Our calculations of pore electrostatic fields and their relationship to the selectivity filter are based on our model, which was derived not from direct structural information but from analogy to the bacterial K+ channel and from many Na+ channel mutational studies. The model is based on the MthK open channel coordinates (Jiang et al. 2002), which are virtually identical to those of the KvAP channel (Lee et al. 2005), rather than the Kv1.2 channel (Long et al. 2005) because the Kv1.2 channel contains a Pro-Val-Pro in S6 that is not present in Na+ channels. The P loops are α-helix-turn-β-strand motifs, which are consistent with the extensive mutational data of residues in that region in several Na+ channel isoforms (Lipkind & Fozzard, 2000). The model's primary value is to guide experiment and to offer insight into possible mechanisms. In addition, there are several assumptions used for the electrostatic calculations that should be noted. Firstly, the protein is assumed to have a homogeneous low dielectric constant, but the correct value is uncertain (Allen et al. 2004). We have used the conservative value of 10, and calculations with lower homogeneous dielectric constant for the protein make relatively little difference (Khan et al. 2002). Secondly, it was assumed for calculation of electrostatic potentials (Gilson & Honig, 1988; Gilson et al. 1988) that the water-filled pore has the dielectric constant of free water (80), but it is no doubt inhomogeneous and lower (Dudley et al. 1995; Sankararamakrishnan et al. 1996; Sansom et al. 1997; Sansom et al. 1998). Consequently, in all of the calculations of electrostatic field and energy profile of the permeating Na+ ion, the estimates were probably underestimated. The possible effect of partial charge generated by the pore α-helices was ignored in our calculations, although this is unlikely to be significant in the open channel model (Jogini & Roux, 2005). All charges were assumed to have a unit value of 1. The assumption of unit charges for the outer vestibule and selectivity filter carboxylates in solutions of physiological pH is likely to be valid because exposure to solutions with alkaline pH produces only a minor increase in current (Khan et al. 2002). The pore model also did not allow adjustment of the side chain orientation of polar and charged residues as a result of the field. Because of these features, the absolute values of electrostatic field are certainly not exact, although the difference calculations would be less influenced by these assumptions.

Role of charge in LA block

The effects of pH and of electric field on LA block from numerous experimental studies have led to the idea that the principal blocking form of LA is its charged form, rather than its neutral one (Hille, 2001). Consistent with this idea, it is the external pH that influences LA block with the effects of pH changes suggesting that the bound LA is almost completely charged at physiological pH (Ritchie & Greengard, 1966; Schwarz et al. 1977). The large negative field that carboxylates in the outer vestibule produce would also be expected to increase the effective proton concentration near the selectivity filter (Khan et al. 2002; Lipkind & Fozzard, 2005). The role of charge in LA block is also supported by experiments using analogues of flecainide, in which a permanently charged derivative preserved use-dependent block and the reduced use-dependent block of more neutral derivatives could be overcome by increasing drug concentration (Liu et al. 2003). The overall impression therefore is that the bound LA is mainly in its charged form, such that it could influence the electrostatic field beneath the selectivity ring. However, several neutral LA drugs also block Na+ channels. The best studied is benzocaine, which is chemically similar to lidocaine but does not contain the alkylamino end. In contrast to lidocaine it produces primarily rested state block with relatively low affinity, and it may therefore not act by the same mechanism as the lidocaine class of LA drugs. Consistent with this idea, our data demonstrate that mutations at Phe-1759 exert little or no effect on rested state/tonic block, a feature that has been reprised in a number of mutational studies that were discussed above. Moreover, mutation of this phenylalanine in NaV1.4, which reduced etidocaine use-dependent block by about 130-fold, only reduced benzocaine block by 2–3-fold (Wang et al. 1998). Before concluding, however, that it is a simple case of charged versus neutral drugs, it should be noted that two neutral benzoate derivatives of benzocaine have been shown to produce significantly more block with repetitive depolarization (Quan et al. 1996), raising the possibility that charge is not absolutely required for the development of use-dependent block. Based on the experiments presented here, charge at position 1759 supports the hypothesis that charged LA drugs alter the electrostatic field within the inner pore in a way that disfavours permeation. If, as predicated by our model of lidocaine binding, physical occlusion of the pore by drug is partial, then electrostatic repulsion is a critical component of the mechanism of LA block.

Acknowledgments

We thank Constance Mlecko and J.R. Liu for their excellent technical assistance and Jack Kyle for producing the constructs. The work was supported by R01HL065661 from the National Institutes of Health (H.A.F. and D.A.H.), T32 HL072742 (M.M.M.), T32 G07839 and the Pritzker Fellowship (G.B.E.), and the Sarnoff Foundation (R.D.S.).

References

- Ahern CA, Eastwood A, Lester H, Dougherty D, Horn R. Investigating cation–pi interactions in the local anesthetic block of voltage gated sodium channels. Biophys J. 2006;22a abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Allen TW, Andersen OS, Roux B. On the importance of atomic fluctuations, protein flexibility, and solvent in ion permeation. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:679–690. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backx PH, Yue DT, Lawrence JH, Marban E, Tomaselli GF. Molecular localization of an ion-binding site within the pore of mammalian sodium channels. Science. 1992;257:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1321496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitah J, Balser JR, Marban E, Tomaselli GF. Proton inhibition of sodium channels: mechanism of gating shifts and reduced conductance. J Membr Biol. 1997;155:121–131. doi: 10.1007/s002329900164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichet D, Grabe M, Jan YN, Jan LY. Electrostatic interactions in the channel cavity as an important determinant of potassium channel selectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14355–14360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606660103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang NS, French RJ, Lipkind GM, Fozzard HA, Dudley S., Jr Predominant interactions between mu-conotoxin Arg-13 and the skeletal muscle Na+ channel localized by mutant cycle analysis. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4407–4419. doi: 10.1021/bi9724927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiamvimonvat N, Perez-Garcia MT, Ranjan R, Marban E, Tomaselli GF. Depth asymmetries of the pore-lining segments of the Na+ channel revealed by cysteine mutagenesis. Neuron. 1996;16:1037–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembowski ET, Lipkind GM, Kyle JW, Fozzard HA, Hanck DA. Orientation and kinetics of Tyr position in Domain IV, S6 control lidocaine affinity in voltage–gated sodium channels. Biophys J. 2006;85a abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley SC, Jr, Todt H, Lipkind G, Fozzard HA. A m-conotoxin-insensitive Na+ channel mutant: possible localization of a binding site at the outer vestibule. Biophys J. 1995;69:1657–1665. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80045-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favre I, Moczydlowski E, Schild L. On the structural basis for ionic selectivity among Na+, K+, and Ca2+ in the voltage-gated sodium channel. Biophys J. 1996;71:3110–3125. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79505-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson MK, Honig B. Calculation of the total electrostatic energy of a macromolecular system: solvation energies, binding energies, and conformational analysis. Proteins. 1988;4:7–18. doi: 10.1002/prot.340040104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson MK, Sharp K, Honig B. Calculating the electrostatic potential of molecules in solution. J Computational Chem. 1988;9:327–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann HA, Tiedeman AA, Chen SF, Brown AM, Kirsch GE. Effects of III–IV linker mutations on human heart Na+ channel inactivation gating. Circ Res. 1994;75:114–122. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway SF, Salgado VL, Wu CH, Narahashi T. Kinetic properties of single sodium channels modified by fenvalerate in mouse neuroblastoma cells. Pflugers Arch. 1989;414:613–621. doi: 10.1007/BF00582125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui K, Lipkind G, Fozzard HA, French RJ. Electrostatic and steric contributions to block of the skeletal muscle sodium channel by μ-conotoxin. J Gen Physiol. 2002;119:45–54. doi: 10.1085/jgp.119.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Lee A, Chen J, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature. 2002;417:515–522. doi: 10.1038/417515a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jogini V, Roux B. Electrostatics of the intracellular vestibule of K+ channels. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:272–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Kyle JW, Hanck DA, Lipkind GM, Fozzard HA. Isoform-dependent interaction of voltage-gated sodium channels with protons. J Physiol. 2006;576:493–501. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.115659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Romantseva L, Lam A, Lipkind G, Fozzard HA. Role of outer ring carboxylates of the rat skeletal muscle sodium channel pore in proton block. J Physiol. 2002;543:71–84. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.021014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrough JT, Gingrich KJ. Quaternary ammonium block of mutant Na+ channels lacking inactivation: features of a transition-intermediate mechanism. J Physiol. 2000;529:93–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00093.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch GE, Alam M, Hartmann HA. Differential effects of sulfhydryl reagents on saxitoxin and tetrodotoxin block of voltage-dependent Na channels. Biophys J. 1994;67:2305–2315. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80716-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Lee A, Chen J, MacKinnon R. Structure of the KvAP voltage-dependent K+ channel and its dependence on the lipid membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15441–15446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507651102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HL, Galue A, Meadows L, Ragsdale DS. A molecular basis for the different local anesthetic affinities of resting versus open and inactivated states of the sodium channel. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55:134–141. doi: 10.1124/mol.55.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkind GM, Fozzard HA. KcsA crystal structure as framework for a molecular model of the Na+ channel pore. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8161–8170. doi: 10.1021/bi000486w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkind GM, Fozzard HA. Molecular modeling of local anesthetic drug binding by voltage-gated sodium channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:1611–1622. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.014803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Atkins J, Kass RS. Common molecular determinants of flecainide and lidocaine block of heart Na+ channels: evidence from experiments with neutral and quaternary flecainide analogues. J Gen Physiol. 2003;121:199–214. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SB, Campbell EB, Mackinnon R. Crystal structure of a mammalian voltage-dependent Shaker family K+ channel. Science. 2005;309:897–903. doi: 10.1126/science.1116269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty MM, Kyle JW, Lipkind GM, Hanck DA. An inner pore residue (Asn406) in the Nav1.5 channel controls slow inactivation and enhances mibefradil block to T-type Ca2+ channel levels. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1514–1523. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.027177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narahashi T. Nerve membrane ionic channels as the primary target of pyrethroids. Neurotoxicology. 1985;6:3–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narahashi T. Toxins that modulate the sodium channel gating mechanism. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;479:133–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb15566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nau C, Wang SY, Strichartz GR, Wang GK. Block of human heart hH1 sodium channels by the enantiomers of bupivacaine. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1022–1033. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200010000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary ME, Chahine M. Cocaine binds to a common site on open and inactivated human heart (Nav1.5) sodium channels. J Physiol. 2002;541:701–716. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.016139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly AO, Khambay BP, Williamson MS, Field LM, Wallace BA, Davies TG. Modelling insecticide-binding sites in the voltage-gated sodium channel. Biochem J. 2006;396:255–263. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan C, Mok WM, Wang GK. Use-dependent inhibition of Na+ currents by benzocaine homologs. Biophys J. 1996;70:194–201. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79563-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale DS, McPhee JC, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of state-dependent block of Na+ channels by local anesthetics. Science. 1994;265:1724–1728. doi: 10.1126/science.8085162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie JM, Greengard P. On the mode of action of local anesthetics. Annu Rev Pharmacol. 1966;6:405–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.06.040166.002201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankararamakrishnan R, Adcock C, Sansom MS. The pore domain of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: molecular modeling, pore dimensions, and electrostatics. Biophys J. 1996;71:1659–1671. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79370-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom MS, Adcock C, Smith GR. Modelling and simulation of ion channels: applications to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J Struct Biol. 1998;121:246–262. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom MS, Smith GR, Adcock C, Biggin PC. The dielectric properties of water within model transbilayer pores. Biophys J. 1997;73:2404–2415. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78269-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satin J, Kyle JW, Chen M, Bell P, Cribbs LL, Fozzard HA, Rogart RB. A mutant of TTX-resistant cardiac sodium channels with TTX-sensitive properties. Science. 1992;256:1202–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlief T, Schonherr R, Imoto K, Heinemann SH. Pore properties of rat brain II sodium channels mutated in the selectivity filter domain. Eur Biophys J. 1996;25:75–91. doi: 10.1007/s002490050020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz W, Palade PT, Hille B. Local anesthetics. Effect of pH on use-dependent block of sodium channels in frog muscle. Biophys J. 1977;20:343–368. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(77)85554-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunami A, Dudley SC, Jr, Fozzard HA. Sodium channel selectivity filter regulates antiarrhythmic drug binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14126–14131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunami A, Tracey A, Glaaser IW, Lipkind GM, Hanck DA, Fozzard HA. Accessibility of mid-segment domain IV, S6 residues of the voltage-gated Na+ channel to methanethiosulfonate reagents. J Physiol. 2004;561:403–413. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.067579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsushima RG, Li RA, Backx PH. Altered ionic selectivity of the sodium channel revealed by cysteine mutations within the pore. J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:463–475. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.4.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedantham V, Cannon SC. Rapid and slow voltage-dependent conformational changes in segment IVS6 of voltage-gated Na+ channels. Biophys J. 2000;78:2943–2958. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76834-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SY, Barile M, Wang GK. Disparate role of Na+ channel D2–S6 residues in batrachotoxin and local anesthetic action. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:1100–1107. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.5.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GK, Quan C, Wang S. A common local anesthetic receptor for benzocaine and etidocaine in voltage-gated μ1 Na+ channels. Pflugers Arch. 1998;435:293–302. doi: 10.1007/s004240050515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright SN, Wang SY, Wang GK. Lysine point mutations in Na+ channel D4–S6 reduce inactivated channel block by local anesthetics. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:733–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarov-Yarovoy V, Brown J, Sharp EM, Clare JJ, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of voltage-dependent gating and binding of pore-blocking drugs in transmembrane segment IIIS6 of the Na+ channel a subunit. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006992200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarov-Yarovoy V, McPhee JC, Idsvoog D, Pate C, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Role of amino acid residues in transmembrane segments IS6 and IIS6 of the Na+ channel a subunit in voltage-dependent gating and drug block. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35393–35401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamponi GW, French RJ. Dissecting lidocaine action: diethylamide and phenol mimic separate modes of lidocaine block of sodium channels from heart and skeletal muscle. Biophys J. 1993;65:2335–2347. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81292-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S-B, Robinson GW. Molecular-dynamics computer simulation of an aqueous NaCl solution: Structure. J Chem Physics. 1992;97:4336–4348. [Google Scholar]