Abstract

Maintenance of dendritic spines, the postsynaptic elements of most glutamatergic synapses in the central nervous system, requires continued activation of AMPA receptors. In organotypic hippocampal slice cultures, chronic blockade of AMPA receptors for 14 days induces a substantial loss of dendritic spines on CA1 pyramidal neurons. Here, using serial section electron microscopy, we show that loss of dendritic spines is paralleled by a significant reduction in synapse density. In contrast, we observed an increased number of asymmetric synapses onto the dendritic shaft, suggesting that spine retraction does not inevitably lead to synapse elimination. Functional analysis of the remaining synapses revealed that hippocampal circuitry compensates for the anatomical loss of synapses by increasing synaptic efficacy. Moreover, we found that the observed morphological and functional changes were associated with altered bidirectional synaptic plasticity. We conclude that continued activation of AMPA receptors is necessary for maintaining structure and function of central glutamatergic synapses.

In the central nervous system, most excitatory synapses occur on spines, which are protrusions of the dendritic tree (Yuste & Bonhoeffer, 2004). Dendritic spines are heterogeneous in shape and have been classified as mushroom, thin and stubby spines, based on the length of their neck and the size of their spine head (Jones & Powell, 1969; Peters & Kaiserman-Abramof, 1970; Harris et al. 1992). Spines undergo actin-dependent shape changes that occur over a large time scale, ranging from seconds (Fischer et al. 1998; Dunaevsky et al. 1999; Korkotian & Segal, 2001) to tens of minutes or even days (Engert & Bonhoeffer, 1999; Maletic-Savatic et al. 1999; Grutzendler et al. 2002; Trachtenberg et al. 2002; Richards et al. 2005).

Time-lapse imaging studies have shown that spines move continuously and rapidly without losing their synaptic contacts (Umeda et al. 2005). This situation may, however, be different when spines retract, as suggested by a study from the mouse barrel cortex showing that spine retraction is associated with synapse elimination (Trachtenberg et al. 2002). Loss of dendritic spines has been reported after sensory deprivation, lesion of synaptic afferents (Valverde, 1971), chronic epilepsy (Muller et al. 1993; Drakew et al. 1996), at low temperatures (Kirov et al. 2004) and following sustained AMPA receptor blockade (McKinney et al. 1999). In the latter study, the effects of a 2 week application of the AMPA receptor antagonist 6-nitro-7-sulphamoylbenzol[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione (NBQX) on dendritic spines were examined in mature hippocampal slice cultures. These experiments clearly showed that activation of AMPA receptors is necessary for the long-term maintenance of spines in CA1 pyramidal cells (McKinney et al. 1999). Using confocal microscopy of fluorescently labelled cells, it was, however, not possible to establish whether the strong reduction in spine number during application of NBQX was accompanied by a loss of synapses or whether the retracting spines retained their synaptic contacts. In the present investigation, we therefore used serial section electron microscopy (ssEM) to determine the total number of synapses and the number of asymmetric synapses on dendritic shafts in control versus NBQX-treated cultures.

In addition to the morphological effects, chronic blockade of glutamate receptors is bound to profoundly influence synaptic functions. Previous studies demonstrated that chronic NMDA receptor blockade during the first 2 weeks of postnatal development markedly increase the frequency of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs), but fails to affect the number of dendritic spines. The increase in synapse number during NMDA receptor blockade is likely to reflect the development of more complex dendritic arbors of CA1 pyramidal cells (Lüthi et al. 2001), as shown by concomitant morphological studies. Interestingly, NMDA receptor blockade profoundly affected synaptic plasticity by lowering the threshold for the induction of long-term potentiation (LTP), but had no effect on the dynamic range of CA3–CA1 synapses (Savic et al. 2003). In view of these data with chronic NMDA receptor blockade, electrophysiological experiments were carried out in the present study to determine the functional consequences of AMPA receptor blockade on the frequency of mEPSCs as well as on the development of synaptic plasticity, in particular LTP and long-term depression (LTD).

The morphological results demonstrate that AMPA receptor blockade induces a significant decrease in the number of spines and synapses and a concomitant increase in the number of asymmetric shaft synapses. Electrophysiological analysis revealed compensatory changes in synaptic function and altered bi-directional synaptic plasticity.

Methods

Organotypic hippocampal slice cultures were prepared as previously described (Gähwiler et al. 1997) following a protocol approved by the Veterinary Department of the Canton of Zurich. Briefly, hippocampi were dissected from 6-day-old Wistar rats, killed by decapitation, and tranverse slices (375 μm thick) were cut and attached to glass coverslips with a drop of thrombin and chicken plasma. Each coverslip and slice was placed in individual sealed test-tubes containing semi-synthetic medium, and maintained on a roller drum in an incubator at 36°C for 2 weeks. The culture medium consisted of 50% Eagle's basal medium with Hanks' salt, 25% balanced salt solution (either Hanks' or Earle's salts), 25% heat-inactivated horse serum, 33.3 mmd-glucose and 0.1 mml-glutamine. Media were purchased from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA, and stock solutions from BioConcept, Allschwil, Switzerland. After 2 weeks, cultures were treated for 2 weeks with 20 μm of the AMPA receptor antagonists NBQX or 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), while sister cultures were kept in control medium. The medium was changed weekly during the first 2 weeks and daily during the next 2 weeks. NBQX and CNQX were obtained from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK).

Reconstruction of dendrites and evaluation of their synaptic contacts

Living CA1 pyramidal cells were impaled with sharp microelectrodes filled with 4% aqueous Lucifer yellow (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Slice cultures were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.025% glutaraldehyde and 15% picric acid in phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.4; 0.1 m) for 2 h at 4°C. After quick freeze–thawing, cultures were incubated with an anti-Lucifer-yellow antibody conjugated with biotin (Molecular Probes) (3 μg ml−1 in 2% horse serum in PBS) for 36 h at 37°C, followed by incubation with an avidin–biotin complex (1:100; Vectastain Elite, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 3 h at room temperature. The immunoreaction was visualized using 0.05% 3,3′;-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and 0.01% hydrogen peroxidase in Tris buffer (pH 7.4). Cultures were osmicated in 1% OsO4 in PB for 30 min, dehydrated in graded alcohols to propylene oxide and embedded in Epon 812 (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland). Flat-embedded slice cultures were examined under the microscope and stratum radiatum areas of injected CA1 pyramidal cells were selected and trimmed. Blocks from these areas were prepared for ultrathin serial sectioning. Dendrites were identified on the basis of their DAB content from ribbons of 70 nm ultrathin sections and imaged, using a digital camera (Gatan 791 multiscan; Gatan, Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA) attached to a EM10C electron microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Images were acquired and processed with the software Digital Micrograph 3.7.4 (Gatan, Inc.), aligned with Adobe Photoshop 7.0.1 (Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA), and all the labelled profiles traced from all the stacks. Finally, synaptic contacts on dendrites were identified and analysed.

Three-dimensional reconstructions of CA1 dendrites were made from aligned serial images, using Reconstruct 1.0.2.1 (Dr J. C. Fiala, Dept. Health Sciences, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA), and rendered with Rhinoceros 3.0 (Robert McNeel & Associates, Seattle, WA, USA). The size of synapses was determined by measuring the diameter of the largest postsynaptic densities (PSDs) in the serial sections of each synapse. However, this is a relative value, because the end-product of our method to detect synapses occludes partially the PSDs. We thus measured the size of the PSDs in those synapses where the diameter of the PSD was clearly detectable. In an additional group, in which the PSD was not clearly visible, we have determined the extension of the synaptic cleft. Spine length was defined as the distance between the synapses and the surface of the dendrites. Statistical comparisons were made using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test.

Electrophysiology

Slice cultures were transferred to a recording chamber mounted on an upright microscope (Axioscope FS, ×40 LD-Achroplan, Zeiss) and were continuously superfused at room temperature with a solution containing (mm): 137 NaCl, 2.7 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 11.6 NaHCO3, 0.4 NaH2PO4, 5.6 glucose, Phenol Red (10 mg l−1), pH 7.4. Before recordings were started slices were superfused for 3 h to completely wash out CNQX.

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were obtained from CA1 pyramidal cells using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA) and pipettes (3–5 MΩ) containing (mm): 140 potassium or caesium gluconate, 10 KCl, 5 Hepes, 1.1 EGTA, 4 MgCl2, 10 phosphocreatine, pH 7.25, 285 mOsM. mEPSCs were recorded in the presence of 0.5 μm TTX 100 μm CPP, 50 μm picrotoxin and 40 μm bicuculline at −70 mV and analysed offline by a computer program (Mini Analysis Program, Synaptosoft, Leonia, CA, USA). The threshold for mEPSC detection was set at 5 pA. To construct cumulative histograms, 100 events were randomly selected from each neuron and pooled. Dual component mEPSCs were recorded in the absence of external magnesium by using a potassium-gluconate-based internal solution containing 10 mm EGTA to prevent induction of synaptic plasticity. The NMDA-receptor-mediated component of dual-component mEPSC waveforms was revealed by subtracting the scaled mean waveform of AMPA-receptor-mediated mEPSCs (recorded in the presence of 100 μm CPP) from the averaged waveform of dual-component mEPSCs (recorded in the absence of glutamal receptor antagonists). At least 100 events (range 100 to >1000) were collected under each experimental condition. The AMPA/NMDA ratio was calculated by using peak amplitudes of the AMPA and NMDA components, respectively.

Field EPSP recordings were obtained by placing a patch-clamp pipette (5 MΩ) filled with 1 m NaCl in CA1 stratum radiatum while stimulating Schaffer-collateral axons using an extracellular stimulation electrode (filled with extracellular medium). A cut was made between CA3 and CA1 to prevent propagation of epileptiform activity. LTP was induced by applying theta burst-patterned stimulation consisting of five trains at 5 Hz composed each of five pulses at 100 Hz. This procedure was repeated twice at an interval of 20 s.

Intracellular recordings were obtained by using an Axoclamp 2A amplifier (Axon Instruments) and sharp microelectrodes (60–80 MΩ) filled with 1 m potassium methylsulphate (pH 7.3). LTD was induced by asynchronous pairing in which the synaptic input was stimulated 800 ms after postsynaptic depolarization (0.5–1.0 nA, 240 ms) (Debanne et al. 1994). Pairing was repeated 100 times at 0.3 Hz.

Evoked potentials were analysed offline using pClamp8 (Axon Instruments). Changes in synaptic strength were quantified for statistical comparisons by normalizing and averaging EPSP slopes during the last 5 min of experiments relative to baseline. All data are reported as means ± s.e.m. Statistical comparisons were made using two-tailed unpaired Student's t test and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

Results

To study the effects of chronic blockade of AMPA receptors on the synaptic morphology of CA1 pyramidal cells, slice cultures prepared from 6-day-old rats were first cultured for 2 weeks in control medium and then exposed to a medium containing NBQX for 2 weeks. At the end of the 4 week period, pyramidal cells were intrasomatically injected with Lucifer yellow and subsequently processed for pre-embedding immunocytochemistry (Fig. 1A, B and D). Three-dimensional reconstructions were obtained from series of EM images of apical tertiary dendrites.

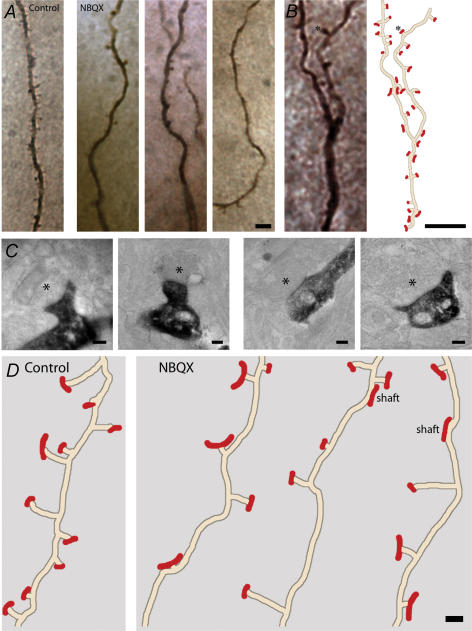

Figure 1. CA1 pyramidal cell dendrites in control and NBQX-treated cultures.

A, pyramidal cells were intrasomatically injected with Lucifer yellow and the preparation was subsequently immunostained. Note the reduction in the number of spines in the three NBQX-treated examples. B, dendrite of a NBQX-treated CA1 pyramidal cell (left), with illustration obtained from ultrathin serial sections (right). Synapses are marked in red. Asterisks point to the same spine in both images. C, electron micrographs of Lucifer yellow-filled dendrites. Protrusions were considered as spines when they extended more than 0.2 μm (first and second images) from the surface of the dendrites; shaft synapses were shorter than 0.2 μm (third and fourth images). Presynaptic elements are marked with asterisks. D, examples of traces from CA1 pyramidal cell dendrites. Synapses are labelled in red and the length of the red mark reflects the size of the PSDs. Note the reduced number of synapses and spines and the increased number of shaft synapses in the NBQX-treated dendrites. Scale bars: A and B, 5 μm; C, 0.2 μm; D, 0.5 μm.

Structures along dendritic trees were identified as synapses if a presynaptic element with an accumulation of synaptic vesicles was found close to an identified postsynaptic element with an asymmetric PSD-like element and if a clear synaptic cleft separated the two opposing membranes. Synaptic contacts were then classified as spine or asymmetric shaft synapses depending on the distance between the emergence of these structures from the dendrites and the corresponding PSDs (Fig. 1C). Protrusions were considered as spines when they extended more than 0.2 μm from the surface of the dendrite; synapses on shorter protrusions were considered to represent shaft synapses. Finally, we determined either the distance between neighbouring spines (interspine distance) and between neighbouring asymmetric synapses (intersynapse distance) or the number of spines/synapses per unit length of dendrite.

Chronic AMPA receptor blockade decreases the number of synapses and dendritic spines on CA1 pyramidal cells

A total of 341.48 μm of tertiary dendrites from 17 segments (average length 20.08 μm) were traced from pyramidal cells (three cells in three cultures) that had been treated with NBQX. In addition, four segments of dendrites from two control cultures (two cells) with a total length of 93.42 μm (average length 23.35 μm) were reconstructed. The analysis of these data revealed a clear reduction in the number of spines (interspine distance: control, 1.07 ± 0.09 μm; NBQX, 2.07 ± 0.16 μm; P < 0.001), thus corroborating the previously described spine loss (McKinney et al. 1999). Additionally, we observed a decrease in the number of synapses in the NBQX-treated cultures (intersynapse distance: control, 1.01 ± 0.08 μm; NBQX, 1.74 ± 0.09 μm; P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A).

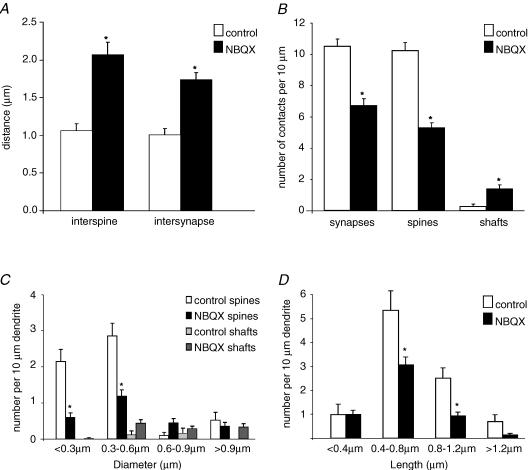

Figure 2. AMPA receptor blockade decreases the number of synapses and spines, and increases the number of shaft synapses and the size of PSDs.

A, NBQX treatment significantly increased interspine and intersynapse distances (P < 0.001). B, the number of synapses and spines per 10 μm dendrite was strongly reduced in NBQX-treated cultures, whereas the number of asymmetric shaft synapses was significantly increased (P < 0.01). C, to determine the effect of NBQX on the size of PSDs, the largest diameter of the PSDs of each synaptic contact was measured and the synapses grouped according to the size of their PSDs (bins of 0.3 μm). Small PSDs were clearly reduced in size by NBQX (up to 0.6 μm, P < 0.001). D, length of spines grouped in 0.4 μm bins. The number of medium (0.4–0.8 μm) and long spines (0.8–1.2 μm) was significantly decreased by NBQX (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively).

Long-term exposure to NBQX increases the number of asymmetrical shaft synapses

The decrease in the number of spines during blockade of AMPA receptors raises the possibility that the retraction of some of the spines results in the generation of shaft synapses. To address this question, we determined the total number of synapses and the number of asymmetrical shaft synapses per 10 μm of tertiary dendrites in control versus NBQX-treated cultures. Interestingly, AMPA receptor blockade increased the number of these shaft synapses fivefold (control, 0.27 ± 0.16; NBQX, 1.43 ± 0.24 shaft synapses per 10 μm dendrite; P < 0.01), corresponding to 18% of all asymmetrical synapses (Fig. 2B). These data suggest that as a result of treatment with NBQX, at least a proportion of spine synapses were transformed into shaft synapses.

Chronic AMPA receptor blockade reduces the size of PSDs and the number of long thin spines

We analysed whether chronic treatment with NBQX had an effect on the size of PSDs on dendritic spines (control, n = 51; NBQX, n = 89). To quantify changes, each reconstructed dendrite was divided into segments of approximately 10 μm and we measured the largest diameter of the PSDs for each synaptic contact from the stack of serial sections. All the synapses were then grouped according to the size of their PSDs (bins of 0.3 μm). The results illustrated in Fig. 2C show that AMPA receptor blockade significantly reduced the number of spine synapses with PSD dimensions up to 0.6 μm (P < 0.001). In addition, the PSD diameter of shaft synapses was not affected.

Since there is a clear correlation between PSD diameter and cleft size, we also measured the extension of synaptic clefts in a second group of synapses (n = 39 for controls, n = 84 in NBQX-treated cultures) where the exact size of the PSDs could not be determined due to occlusion by the end-product of our histological processing. AMPA receptor blockade significantly decreased the number of spine synapses with synaptic cleft diameters <0.3 μm (from 2.16 to 0.72 spine synapses per 10 μm of dendrite; P < 0.004). There was also a reduction of spine synapses with cleft sizes between 0.3 and 0.6 μm (1.66–1.14 spine synapses per 10 μm of dendrite) following application of NBQX, thus supporting the findings obtained with measurements of PSDs.

We also investigated whether chronic AMPA receptor blockade altered the length of spines. For this purpose, spine length was determined and the spines grouped according to their length (in bins of 0.4 μm). NBQX clearly reduced the length of spines (Fig. 2D), with greatest effects on medium (0.4–0.8 μm) (P < 0.01) and relatively long spines (0.8–1.2 μm) (P < 0.001).

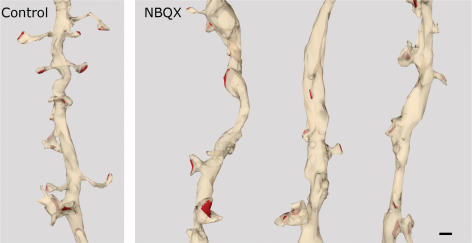

All analyses described above were carried out on traced dendrites from reconstructed volumes of tissue. To corroborate the data, some dendrites were completely three-dimensionally reconstructed with rendering of the traces (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. 3-D reconstructions of CA1 dendrites.

Apical dendrites of CA1 pyramidal cells in control and NBQX-treated cultures were three-dimensionally reconstructed based on the traces used for the quantification. Scale bar, 0.5 μm.

Chronic AMPA receptor blockade increases mEPSC amplitude, but does not alter mEPSC frequency and AMPA/NMDA ratio

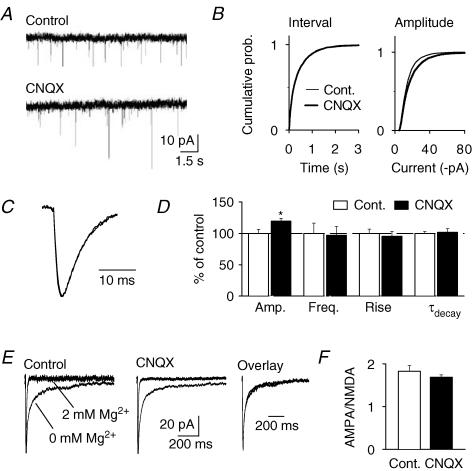

To examine whether the observed loss of synapses along with the increased number of shaft synapses was associated with any alterations in synaptic function, we compared mEPSCs recorded from CA1 pyramidal cells in control slices and in slices subjected to chronic AMPA receptor blockade. Since NBQX could not be completely washed-out from treated cultures, we used the related competitive AMPA receptor antagonist CNQX for these experiments. Even though chronic AMPA receptor blockade induced a marked loss of glutamatergic synapses, the frequency of mEPSCs – a parameter reflecting the number of release sites along with the probability of release – was not reduced in CNQX-treated slices (control, 2.57 ± 0.42 Hz, n = 10; CNQX, 2.50 ± 0.35 Hz, n = 10; P > 0.05) (Fig. 4A and B). In contrast, we found mEPSC amplitude to be slightly increased as compared with control slices (control, −14.3 ± 0.9 pA, n = 10; CNQX, −17.0 ± 0.6 pA, n = 10; P < 0.05) (Fig. 4A and B), with no change in the kinetics (10–90% rise time: control, 1.79 ± 0.12 ms, n = 10; CNQX, 1.71 ± 0.13 ms, n = 10; τdecay: control, 5.57 ± 0.17 ms, n = 10; CNQX, 5.65 ± 0.34 ms, n = 10) (Fig. 4C and D).

Figure 4. AMPA receptor blockade increases mEPSC amplitude but does not alter mEPSC frequency or AMPA/NMDA ratio.

A, sample traces from a control culture (top) and a culture treated with 40 μm CNQX (bottom) for 14 days. B, cumulative distributions of inter-mEPSC intervals (left) and amplitudes (right) containing 100 randomly selected events from each cell (total: 1000 events per group) revealing a small increase in amplitude for CNQX-treated cultures (P < 0.05). C, averaged, scaled and superimposed traces from control and CNQX-treated cultures showing no change in mEPSC kinetics. Traces were obtained by averaging the scaled mean waveforms from each experiment. D, summary graph comparing mEPSCs recorded from control (n = 10) and CNQX-treated slices (n = 10). E, averaged traces of mEPSCs recorded in the presence and in absence of extracellular Mg2+ from control (left) and CNQX-treated slices (middle). Traces were obtained by averaging the scaled mean waveforms from each experiment. Right, superimposed and scaled traces from control and CNQX-treated cultures illustrating identical kinetics of mEPSC waveforms recorded in the absence of extracellular Mg2+. F, summary graph showing equal AMPA/NMDA ratios in control (n = 8) and CNQX-treated slices (n = 7; P > 0.05).

We observed that chronic AMPA receptor blockade leads to a selective loss of synapses with small PSDs. Because at CA3–CA1 synapses the size of dendritic spines and associated PSDs correlates with the number of synaptic AMPA, but not NMDA receptors (Nusser et al. 1998; Takumi et al. 1999; Matsuzaki et al. 2001), we determined the relative contribution of AMPA and NMDA receptors to spontaneous synaptic transmission. We recorded dual-component mEPSCs in the absence of extracellular Mg2+ and measured the amplitude ratio of the AMPA and the NMDA component by acute application of the AMPA receptor antagonist NBQX. The synaptic AMPA/NMDA ratio was unchanged in CNQX-treated slices as compared with control slices (control, 1.83 ± 0.14, n = 8; CNQX, 1.69 ± 0.06, n = 7; P > 0.05) (Fig. 4E and F).

Thus, homeostatic changes in synaptic function appear to compensate for the observed loss in synapse number. The constant AMPA/NMDA ratio at functional synapses suggests that synaptic homeostasis upon chronic AMPA receptor blockade may involve a concerted enhancement in the efficacy of AMPA and NMDA receptor-mediated transmission. Alternatively, chronic AMPA receptor blockade might induce a selective loss of functionally silent synapses.

Absence of LTP and increased LTD after chronic AMPA receptor blockade

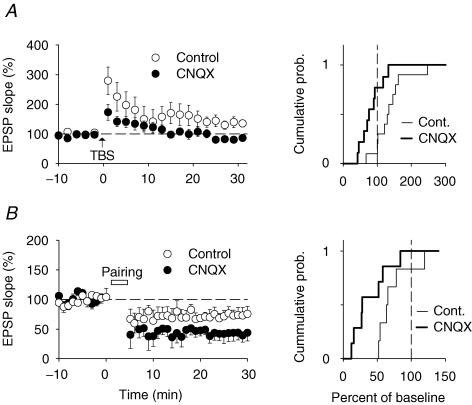

Synaptic glutamate receptor content and dendritic spine geometry are thought to reflect synaptic strength at CA3–CA1 synapses (Matsuzaki et al. 2004). Moreover, induction of synaptic plasticity is a highly cooperative process that most likely depends on synaptic density. To assess whether synaptic plasticity was altered by chronic AMPA receptor blockade, we performed a series of extracellular field recordings in CA1 stratum radiatum while stimulating Schaffer-collateral fibres using an extracellular stimulation electrode. In control slices delivery of a theta-burst-patterned train of stimuli-induced LTP (136 ± 15% of baseline, n = 10; P < 0.05) (Fig. 5A). In contrast, we did not observe any LTP in slices treated with CNQX (81 ± 10% of baseline, n = 9; P > 0.05) (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. CA3–CA1 synapses express decreased LTP and increased LTD after chronic AMPA receptor blockade.

A, left, summary graph illustrating lack of long-term potentiation (LTP) in CNQX-treated slices (n = 9) as compared with control slices (n = 10; P < 0.05). Arrow indicates LTP induction by theta-burst stimulation (TBS). Right, cumulative distribution plot of changes in baseline fEPSP slope after induction of LTP, showing absence of LTP in CNQX-treated slices. B, left, summary graph illustrating increased long-term depression (LTD) induced by asynchronous pairing of pre- and postsynaptic activity in CNQX-treated slices (n = 7) as compared with control slices (n = 6; P < 0.05). Right, cumulative distribution plot of changes in baseline EPSP slope after induction of LTD, showing enhanced LTD in CNQX-treated slices.

Next, we sought to induce LTD using prolonged stimulation of Schaffer-collateral axons at 1 Hz (Dudek & Bear, 1992). Delivery of 900 stimuli at 1 Hz led to a complete disappearance of postsynaptic responses (not shown). Since in organotypic slice cultures it is difficult to reliably control for the number of stimulated axons by monitoring the presynaptic fibre volley, we could not rule out that the disappearance of postsynaptic responses reflected a loss of synapses rather than LTD. We therefore resorted to sharp-microelectrode intracellular recordings and induced LTD by asynchronous pairing of presynaptic stimulation with postsynaptic depolarization steps (Debanne et al. 1994). LTD induced by asynchronous pairing was significantly enhanced in CNQX-treated slices as compared to control slices (control, 72 ± 10% of baseline, n = 6; CNQX, 40 ± 10% of baseline, n = 7; P < 0.05) (Fig. 5B). These experiments demonstrate that chronic AMPA receptor blockade alters bi-directional synaptic plasticity at CA3–CA1 synapses.

Discussion

In the present study we combined electron microscopic and electrophysiological approaches to determine the synaptic modifications that follow long-term blockade of AMPA receptors in hippocampal slice cultures. The morphological experiments provided clear evidence for pruning of dendritic spines in CA1 pyramidal cells, together with a complex modification of the synaptic network. The spine elimination previously observed with confocal microscopy (McKinney et al. 1999) thus has two components: a loss of dendritic spines and their associated synapses, and a fivefold increase in the population of asymmetrical synapses located on dendritic shafts. In addition, analysis of the spine types identified long thin spines as the group most affected by the NBQX treatment. These short-neck spines, which probably represent the fraction of spines that retracts, maintain their synaptic contacts.

Our data show that AMPA receptor blockade results in the loss of a high proportion of spines. Some of them probably retract into the dendrites, thereby losing their synaptic contacts. During recent years, several in vivo studies have investigated the stability of dendritic spines in different brain areas, especially with respect to experience-dependent synaptic plasticity (Grutzendler et al. 2002; Trachtenberg et al. 2002; Holtmaat et al. 2005; Holtmaat et al. 2006). Although the quantitative results differ in the brain areas studied, there is clear evidence that a proportion of spines disappears over periods of days. Two-photon microscopy in combination with ssEM has been used to demonstrate that pruned spines, from apical dendrites of layer 5 pyramidal neurons in the mouse barrel cortex, do not maintain their synaptic contacts (Trachtenberg et al. 2002). That study is consistent with our observations of synapse loss. However, in addition we observed an increase in the number of shaft synapses, which most probably resulted from retraction of short-neck spines which maintain synaptic contacts. Therefore, the structure of these synapses might change from spine to shaft synapse. Interestingly, reappearance of spines was reported to occur at the original dendritic sites after recovery from hypoxia-induced spine loss (Hasbani et al. 2001).

We hypothesize that, to a certain extent, all spine types are affected by AMPA receptor blockade, but the consequences of retraction may vary greatly. The spines with small PSDs and long necks have smaller areas of attachment with presynaptic boutons, and their retraction may result in the loss of the synaptic contact. The different sensitivity of the various spine types to the chronic AMPA receptor blockade is consistent with other properties described as spine-type dependent. Thereby, thin spines are considered to be more plastic structures and to present less mature synapses (Koch & Zador, 1993; Ziv & Smith, 1996; Fiala et al. 1998; Majewska et al. 2000a,b; Yuste et al. 2000; Portera-Cailliau et al. 2003; Wallace & Bear, 2004). Furthermore, they are more motile (Holtmaat et al. 2005) and long-term potentiation, proposed as the cellular basis for learning and memory, produces spine enlargement especially in this type (Matsuzaki et al. 2004). On the other hand, the large mushroom spines are described as being more stable (Trachtenberg et al. 2002; Holtmaat et al. 2005).

Prolonged blockade of synaptic activity induces cell-wide compensatory changes in synaptic strength, a phenomenon referred to as homeostatic plasticity (Turrigiano & Nelson, 2004). At neocortical synapses, homeostatic plasticity is thought to be mediated by postsynaptic mechanisms, such as enhanced accumulation of postsynaptic AMPA receptors (Wierenga et al. 2005). Consistent with this idea we found that chronic AMPA receptor blockade increased mEPSC amplitude, although to a much smaller extent to what has been described in cultured neocortical neurons (Turrigiano et al. 1998). In accordance with previous findings (Watt et al. 2000), we found that synaptic AMPA and NMDA receptors are coregulated leaving the synaptic AMPA/NMDA ratio unaltered. Although our anatomical data clearly demonstrate that chronic AMPA receptor blockade induces a marked loss of synaptic contacts, this had no effect on mEPSC frequency. In principle, this could be explained by an apparent increase in mEPSC frequency in CNQX-treated cultures caused by a more efficient detection of mEPSCs with enlarged amplitudes. However, given that the increase in mEPSC amplitude was very modest, this suggests that hippocampal circuitry has the capacity to compensate, at least in part, for a decrease in synaptic density by adjusting synaptic efficacy, either through an increase in quantal content, or by increasing the relative number of functional postsynaptic elements. Alternatively, loss of synapses might be largely restricted to silent synapses, without any effect on functional, AMPA receptor containing synapses. Given the pronounced loss of small spines, which most likely represent the morphological correlate of postsynaptically silent synapses (Nusser et al. 1998; Takumi et al. 1999), we feel that it is unlikely that the lack of effect on mEPSC frequency can be accounted for by an activation of silent synapses, but may rather involve a preferential loss of silent synapses and/or an increase in quantal content at functional synapses. Indeed, findings from cultured hippocampal neurons indicate that homeostatic plasticity of presynaptic quantal content can be induced by chronic activity blockade (Bacci et al. 2001; Murthy et al. 2001; Thiagarajan et al. 2005).

In addition to homeostatic plasticity of synaptic transmission, we found that chronic AMPA receptor blockade alters bidirectional modifiability of synaptic strength at CA3–CA1 synapses. CNQX-treated slices exhibited a complete absence of LTP and enhanced LTD. Similar to our previous findings with chronic NMDA receptor blockade (Savic et al. 2003), metaplastic changes induced by CNQX seemed to occur without affecting the dynamic range of synaptic plasticity. One possible interpretation of this finding is that chronic AMPA receptor blockade leads to an apparent occlusion of LTP because already potentiated synapses, with larger PSDs and spine heads (Takumi et al. 1999; Matsuzaki et al. 2004) are less affected than smaller and weaker synapses. Consistent with this idea, we found large mushroom-shaped synapses to be more resistant to chronic activity blockade. Alternatively, spine retraction, and the consequent formation of synapses onto the dendritic shaft, might lead to alterations in the compartmentalization and/or mechanisms of Ca2+ signalling necessary for the proper induction of bidirectional plasticity (Yuste et al. 2000; Thiagarajan et al. 2005).

Taken together, our data indicate that chronic blockade of AMPA receptors leads to complex morphological and functional changes in hippocampal circuitry. In a previous study using confocal laser scanning microscopy, we showed that AMPA receptor activation is necessary to maintain dendritic spines. In view of the significant decrease in the number of synapses seen in the present EM investigation in response to chronic application of NBQX, we conclude that activation of AMPA receptors also contributes to the maintenance of synaptic contacts. Loss of synaptic contacts, in turn, can lead to compensatory changes in synaptic transmission and plasticity.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Rietschin, L. Heeb, D. Göckeritz-Dujmovic, L. Spassova and R. Schöb for technical assistance; R. Dürr for helping with the statistical analysis; and U. Gerber for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- Bacci A, Coco S, Pravettoni E, Schenk U, Armano S, Frassoni C, Verderio C, De Camilli P, Matteoli M. Chronic blockade of glutamate receptors enhances presynaptic release and downregulates the interaction between synaptophysin-synaptobrevin-vesicle-associated membrane protein 2. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6588–6596. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06588.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM. Asynchronous pre- and postsynaptic activity induces associative long-term depression in area CA1 of the rat hippocampus in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:1148–1152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakew A, Muller M, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM, Frotscher M. Spine loss in experimental epilepsy: quantitative light and electron microscopic analysis of intracellularly stained CA3 pyramidal cells in hippocampal slice cultures. Neuroscience. 1996;70:31–45. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00379-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek SM, Bear MF. Homosynaptic long-term depression in area CA1 of hippocampus and effects of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4363–4367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunaevsky A, Tashiro A, Majewska A, Mason C, Yuste R. Developmental regulation of spine motility in the mammalian central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13438–13443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engert F, Bonhoeffer T. Dendritic spine changes associated with hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity. Nature. 1999;399:66–70. doi: 10.1038/19978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala JC, Feinberg M, Popov V, Harris KM. Synaptogenesis via dendritic filopodia in developing hippocampal area CA1. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8900–8911. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08900.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M, Kaech S, Knutti D, Matus A. Rapid actin-based plasticity in dendritic spines. Neuron. 1998;20:847–854. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80467-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gähwiler BH, Capogna M, Debanne D, McKinney RA, Thompson SM. Organotypic slice cultures: a technique has come of age. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:471–477. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grutzendler J, Kasthuri N, Gan WB. Long-term dendritic spine stability in the adult cortex. Nature. 2002;420:812–816. doi: 10.1038/nature01276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Jensen FE, Tsao B. Three-dimensional structure of dendritic spines and synapses in rat hippocampus (CA1) at postnatal day 15 and adult ages: implications for the maturation of synaptic physiology and long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2685–2705. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02685.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasbani MJ, Schlief ML, Fisher DA, Goldberg MP. Dendritic spines lost during glutamate receptor activation reemerge at original sites of synaptic contact. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2393–2403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02393.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmaat AJ, Trachtenberg JT, Wilbrecht L, Shepherd GM, Zhang X, Knott GW, Svoboda K. Transient and persistent dendritic spines in the neocortex in vivo. Neuron. 2005;45:279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmaat A, Wilbrecht L, Knott GW, Welker E, Svoboda K. Experience-dependent and cell-type-specific spine growth in the neocortex. Nature. 2006;441:979–983. doi: 10.1038/nature04783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG, Powell TP. Morphological variations in the dendritic spines of the neocortex. J Cell Sci. 1969;5:509–529. doi: 10.1242/jcs.5.2.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirov SA, Petrak LJ, Fiala JC, Harris KM. Dendritic spines disappear with chilling but proliferate excessively upon rewarming of mature hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2004;127:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch C, Zador A. The function of dendritic spines: devices subserving biochemical rather than electrical compartmentalization. J Neurosci. 1993;13:413–422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00413.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkotian E, Segal M. Regulation of dendritic spine motility in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6115–6124. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06115.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüthi A, Schwyzer L, Mateos JM, Gähwiler BH, McKinney RA. NMDA receptor activation limits the number of synaptic connections during hippocampal development. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1102–1107. doi: 10.1038/nn744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewska A, Brown E, Ross J, Yuste R. Mechanisms of calcium decay kinetics in hippocampal spines: role of spine calcium pumps and calcium diffusion through the spine neck in biochemical compartmentalization. J Neurosci. 2000a;20:1722–1734. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01722.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewska A, Tashiro A, Yuste R. Regulation of spine calcium dynamics by rapid spine motility. J Neurosci. 2000b;20:8262–8268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08262.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maletic-Savatic M, Malinow R, Svoboda K. Rapid dendritic morphogenesis in CA1 hippocampal dendrites induced by synaptic activity. Science. 1999;283:1923–1927. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5409.1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki M, Ellis-Davies GC, Nemoto T, Miyashita Y, Iino M, Kasai H. Dendritic spine geometry is critical for AMPA receptor expression in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1086–1092. doi: 10.1038/nn736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki M, Honkura N, Ellis-Davies GC, Kasai H. Structural basis of long-term potentiation in single dendritic spines. Nature. 2004;429:761–766. doi: 10.1038/nature02617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney RA, Capogna M, Durr R, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM. Miniature synaptic events maintain dendritic spines via AMPA receptor activation. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:44–49. doi: 10.1038/4548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M, Gähwiler BH, Rietschin L, Thompson SM. Reversible loss of dendritic spines and altered excitability after chronic epilepsy in hippocampal slice cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:257–261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy VN, Schikorski T, Stevens CF, Zhu Y. Inactivity produces increases in neurotransmitter release and synapse size. Neuron. 2001;32:673–682. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00500-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Lujan R, Laube G, Roberts JD, Molnar E, Somogyi P. Cell type and pathway dependence of synaptic AMPA receptor number and variability in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1998;21:545–559. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80565-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Kaiserman-Abramof IR. The small pyramidal neuron of the rat cerebral cortex. The perikaryon, dendrites and spines. Am J Anat. 1970;127:321–355. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001270402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portera-Cailliau C, Pan DT, Yuste R. Activity-regulated dynamic behavior of early dendritic protrusions: evidence for different types of dendritic filopodia. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7129–7142. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-18-07129.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards DA, Mateos JM, Hugel S, de Paola V, Caroni P, Gähwiler BH, McKinney RA. Glutamate induces the rapid formation of spine head protrusions in hippocampal slice cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6166–6171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501881102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savic N, Lüthi A, Gähwiler BH, McKinney RA. N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor blockade during development lowers long-term potentiation threshold without affecting dynamic range of CA3–CA1 synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5503–5508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0831035100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takumi Y, Ramirez-Leon V, Laake P, Rinvik E, Ottersen OP. Different modes of expression of AMPA and NMDA receptors in hippocampal synapses. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:618–624. doi: 10.1038/10172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiagarajan TC, Lindskog M, Tsien RW. Adaptation to synaptic inactivity in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2005;47:725–737. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachtenberg JT, Chen BE, Knott GW, Feng G, Sanes JR, Welker E, Svoboda K. Long-term in vivo imaging of experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in adult cortex. Nature. 2002;420:788–794. doi: 10.1038/nature01273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG, Leslie KR, Desai NS, Rutherford LC, Nelson SB. Activity-dependent scaling of quantal amplitude in neocortical neurons. Nature. 1998;391:892–896. doi: 10.1038/36103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG, Nelson SB. Homeostatic plasticity in the developing nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:97–107. doi: 10.1038/nrn1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeda T, Ebihara T, Okabe S. Simultaneous observation of stably associated presynaptic varicosities and postsynaptic spines: morphological alterations of CA3–CA1 synapses in hippocampal slice cultures. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:264–274. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde F. Rate and extent of recovery from dark rearing in the visual cortex of the mouse. Brain Res. 1971;33:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace W, Bear MF. A morphological correlate of synaptic scaling in visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6928–6938. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1110-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt AJ, van Rossum MC, MacLeod KM, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Activity coregulates quantal AMPA and NMDA currents at neocortical synapses. Neuron. 2000;26:659–670. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierenga CJ, Ibata K, Turrigiano GG. Postsynaptic expression of homeostatic plasticity at neocortical synapses. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2895–2905. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5217-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuste R, Bonhoeffer T. Genesis of dendritic spines: insights from ultrastructural and imaging studies. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:24–34. doi: 10.1038/nrn1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuste R, Majewska A, Holthoff K. From form to function: calcium compartmentalization in dendritic spines. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:653–659. doi: 10.1038/76609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziv NE, Smith SJ. Evidence for a role of dendritic filopodia in synaptogenesis and spine formation. Neuron. 1996;17:91–102. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]