Abstract

TRPM8, a member of the melastatin subfamily of transient receptor potential (TRP) cation channels, is activated by voltage, low temperatures and cooling compounds. These properties and its restricted expression to small sensory neurons have made it the ion channel with the most advocated role in cold transduction. Recent work suggests that activation of TRPM8 by cold and menthol takes place through shifts in its voltage-activation curve, which cause the channel to open at physiological membrane potentials. By contrast, little is known about the actions of inhibitors on the function of TRPM8. We investigated the chemical and thermal modulation of TRPM8 in transfected HEK293 cells and in cold-sensitive primary sensory neurons. We show that cold-evoked TRPM8 responses are effectively suppressed by inhibitor compounds SKF96365, 4-(3-chloro-pyridin-2-yl)-piperazine-1-carboxylic acid (4-tert-butyl-phenyl)-amide (BCTC) and 1,10-phenanthroline. These antagonists exert their effect by shifting the voltage dependence of TRPM8 activation towards more positive potentials. An opposite shift towards more negative potentials is achieved by the agonist menthol. Functionally, the bidirectional shift in channel gating translates into a change in the apparent temperature threshold of TRPM8-expressing cells. Accordingly, in the presence of the antagonist compounds, the apparent response-threshold temperature of TRPM8 is displaced towards colder temperatures, whereas menthol sensitizes the response, shifting the threshold in the opposite direction. Co-application of agonists and antagonists produces predictable cancellation of these effects, suggesting the convergence on a common molecular process. The potential for half maximal activation of TRPM8 activation by cold was ∼140 mV more negative in native channels compared to recombinant channels, with a much higher open probability at negative membrane potentials in the former. In functional terms, this difference translates into a shift in the apparent temperature threshold for activation towards higher temperatures for native currents. This difference in voltage-dependence readily explains the high threshold temperatures characteristic of many cold thermoreceptors. The modulation of TRPM8 activity by different chemical agents unveils an important flexibility in the temperature–response curve of TRPM8 channels and cold thermoreceptors.

Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels comprise an extensive family of cation-permeable channels found in animals and fungi. More than 30 members have been identified in mammals, with a wide expression profile (Montell et al. 2002; Clapham, 2003). Targeted gene deletions of several TRP channels have revealed some of their key physiological functions, which include pheromone sensory signalling (TRPC2), innocuous heat sensation (TRPV3), osmoregulatory responses (TRPV4), taste transduction (TRPM5) and nociception (TRPV1 and TRPA1) (for references, see original publications by Caterina et al. 2000; Bautista et al. 2006; Kwan et al. 2006; and reviews by Fleig & Penner, 2004; Wissenbach et al. 2004; Desai & Clapham, 2005; Pedersen et al. 2005; Nilius et al. 2007). Many TRP channels have polymodal activation and several are thought to play important roles in somatosensory thermal transduction (reviewed by Jordt et al. 2003; McKemy, 2005; Dhaka et al. 2006).

TRPM8 is a non-selective calcium-permeable TRP channel that is activated by cold and menthol, and is postulated to play a critical role in the transduction of moderate cold stimuli that give rise to cool sensations (McKemy et al. 2002; Peier et al. 2002; Reid, 2005; Voets et al. 2007). TRPM8 has a limited expression profile in the nervous system, restricted to a subpopulation of primary sensory neurons of small diameter in dorsal root and trigeminal ganglia (McKemy et al. 2002; Peier et al. 2002). Most cold-sensitive neurons are excited by both cooling and menthol (Reid & Flonta, 2001; McKemy et al. 2002; Viana et al. 2002; Thut et al. 2003), and also express TRPM8 mRNA transcripts (Nealen et al. 2003). Moreover, many cold-sensitive neurons express a non-selective cation current (Icold) with biophysical and pharmacological properties consistent with the properties of TRPM8-dependent currents in transfected cells (Okazawa et al. 2002; Reid et al. 2002). In addition, TRPM8 has been found in prostate tissue, where its physiological function remains uncertain (Tsavaler et al. 2001; Zhang & Barritt, 2006).

Although TRP channels were originally thought to be voltage independent, it now seems that several of them exhibit weak voltage dependence (Hofmann et al. 2003; Nilius et al. 2003, 2005; Brauchi et al. 2004; Voets et al. 2004). In the case of TRPM8, the voltage dependence manifests as activation upon depolarization to positive transmembrane potentials, and a rapid and voltage-dependent closure at negative potentials (Brauchi et al. 2004; Voets et al. 2004). Cooling shifts the activation curve of TRPM8 towards more negative potentials, and thus increases the probability of channel openings at physiological membrane potentials. A similar shift is induced by the cooling agent menthol, causing the channel to activate at temperatures above 30°C (Voets et al. 2004).

Despite the important physiological functions of TRP channels, knowledge about their biophysical properties is still modest compared to that of other ion channels (Owsianik et al. 2006) and pharmacological tools to study or modulate them are very limited (Desai & Clapham, 2005; Dhaka et al. 2006). A notable exception is the pharmacology of the heat- and vanilloid-activated channel TRPV1, which has expanded significantly in the past few years (Garcia-Martinez et al. 2002; Valenzano et al. 2003; Krause et al. 2005). By contrast, reports on means to regulate TRPM8 activity are scarce and incomplete. Recent studies show that ethanol inhibits TRPM8 function at concentrations of the order of 0.5–3% (Weil et al. 2005; Benedikt et al. 2007). In addition, a number of known TRPV1 antagonists have been tested on heterologously expressed TRPM8 channels, such as the complex between the divalent copper ion and 1,10-phenanthroline (Cu–Phe), capsazepine, 4-(3-chloro-pyridin-2-yl)-piperazine-1-carboxylic acid (4-tert-butyl-phenyl)-amide (BCTC) and the related thio-BCTC and (2R)-4-C3-chloro-2-pyridinyl)-2-methyl- N-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1-piperazinecarboxamide (CTPC), the urea derivative SB-452533 and the cinnamide derivative SB-366791 (Behrendt et al. 2004; Weil et al. 2005; Madrid et al. 2006). With the exception of BCTC and ethanol, studies with these antagonists have been limited to responses evoked by application of menthol at constant room temperature – a mixture of chemical and physiological stimuli – thereby revealing little information about the nature and mechanism of the inhibition. Furthermore, almost nothing is known about the actions of these or other TRPM8 blockers on native thermoreceptors.

In many cases, the lack of specific blockers prevents or impairs a proper functional characterization of the channel in physiological systems. The availability of selective and potent TRPM8 channel antagonists is an essential tool in clarifying the role of different ion channels in thermal responses of intact cold receptors. In addition, modulators of TRPM8 activity have significant therapeutic potential in the treatment of prostate cancer (Zhang & Barritt, 2006). Here, we studied SKF96365, BCTC and 1,10-phenanthroline for their blocking effects on cold-activated TRPM8 responses. BCTC and SKF96365, which exhibited high antagonist potency, were subsequently characterized with respect to their mechanism of inhibition; results suggest a similar but opposite mode of action to that of menthol. The results obtained on recombinant channels were verified on native cold thermoreceptors.

Methods

Cloning of TRPM8 in pcINeo/IRES–GFP

Transfection of HEK293 cells with TRPM8 was carried out using the recombinant bicistronic expression plasmid pcINeo–TRPM8–IRES–GFP, which carries the protein-coding region of rat TRPM8 (accession number, AY072788) and the green fluorescent protein (GFP) coupled by an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) sequence. GFP fluorescence could thus be used to identify TRPM8-expressing cells. The bicistronic vector pcINeo–IRES–GFP was provided by Jan Eggermont (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium) and pcDNA3–TRPM8 was made available by David Julius (University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA). The new construct was verified by automatic sequencing.

Cell culture

HEK293 cells were obtained from the European Collection of Cell Cultures (Salisbury, UK). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics, and plated in 2 cm × 2 cm wells at 4–5 × 105 cells well−1. Next, 20–24 h after plating, the cells were transfected with the TRPM8–IRES–GFP construct by incubating them with a solution containing the plasmid DNA (2 μg well−1) and Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; 3 μl well−1) for 4–6 h. Subsequently, the cells were trypsinized and replated on laminin-coated round coverslips (12 mm diameter) at 8–10 × 104 cells coverslip−1. GFP-positive cells were selected for calcium-imaging or electrophysiology experiments 20–72 h after transfection.

HEK293 cells stably expressing rat TRPM8 channels (CR#1 cells) were kindly provided by Ramón Latorre (Center for Scientific Studies, Valdivia, Chile). They were cultured as described in by Brauchi et al. (2004).

All experimental procedures concerning animals were carried out according to the Spanish Royal Decree 223/1988 and the European Community Council directive 86/609/EEC. Trigeminal ganglion neurons from neonatal mice were cultured as previously described (de la Pena et al. 2005). In brief, newborn Swiss OF1 mice (postnatal day 1–5) were anaesthetized with ether and decapitated. The trigeminal ganglia were isolated and incubated with 1 mg ml−1 collagenase type IA, and cultured in a medium containing 45% DMEM, 45% F-12 and 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen), supplemented with 4 mml-glutamine (Invitrogen), 200 μg ml−1 streptomycin, 125 μg ml−1 penicillin, 17 mm glucose and nerve growth factor (NGF, mouse 7S, 100 ng ml−1, Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain). Cells were plated on poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips and used after 1–3 days in culture.

Calcium imaging

The calcium imaging experiments were conducted with the fluorescent indicator Fura-2. Prior to each experiment, the cells were incubated with 5 μm acetoxymethylester form of Fura-2 (Molecular Probes Europe, the Netherlands) for 45 min at 37°C. Fluorescence measurements were made with a Zeiss Axioskop FS (Germany) upright microscope fitted with an ORCA ER CCD camera (Hamamatsu, Japan). Fura-2 was excited at 340 and 380 nm (excitation time, 200 or 300 ms) with a rapid switching monochromator (TILL Photonics, Germany), and the emitted fluorescence was filtered with a 510 nm long-pass filter. Mean fluorescence intensity ratios (F340/F380) were displayed on-line with Axon Imaging Workbench or Metafluor software (Molecular Devices, PA, USA). The calcium imaging experiments were performed simultaneously with temperature recordings. The bath solution, referred to as ‘control solution’, contained (mm): NaCl 140, KCl 3, CaCl2 2.4, MgCl2 1.3, Hepes 10 and glucose 10, and was adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were performed simultaneously with temperature recordings. Standard patch pipettes (3–5 MΩ) were made of borosilicate glass capillaries (Harvard Apparatus Ltd, UK) and contained (mm): CsCl 140, MgCl2 0.6, EGTA 1 and Hepes 10; 278 mosmol kg−1, pH adjusted to 7.4 with CsOH. In Icold threshold experiments, the internal solution contained (mm): KCl 140, NaCl 6, MgCl2 0.6, EGTA 1, NaATP 1, NaGTP 0.1 and Hepes 10; 282 mosmol kg−1, pH adjusted to 7.4 with KOH). The bath solution used was the same as in the calcium imaging experiments. For whole-cell recordings in trigeminal neurons, patch pipettes had a resisitance of 7–8 MΩ. To measure the activation of Icold in neurons, the bath solution contained (mm): NaCl 140, KCl 3, MgCl2 1.3, CaCl2 0.1, Hepes 10, glucose 10 and TTX 0.5 × 10−3; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The pipette solution contained (mm): CsCl 140, MgCl2 0.6, EGTA 1, Hepes 10, ATPNa2 1 and GTPNa 0.1; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with CsOH. These modifications were necessary to minimize large voltage-dependent currents. Current signals were recorded with an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier (Molecular Devices). Stimulus delivery and data acquisition were performed using pCLAMP9 software (Molecular Devices).

Chemical modulators

The chemical substances studied for their modulatory effect on TRPM8 were the cooling agent l-menthol (Scharlau, Spain), and the antagonists 1,10-phenanthroline (Sigma), SKF96365 (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) and BCTC which was a kind gift from Grünenthal GmbH Aachen (Germany).

Temperature stimulation

Coverslips with cultured cells were placed in a microchamber and continuously perfused with solutions warmed to 32–34°C. The temperature was adjusted with a water-cooled Peltier device placed at the inlet of the chamber, and controlled by a feedback device. Cold sensitivity was investigated with a temperature drop to 15–18°C (see Fig. 1E).

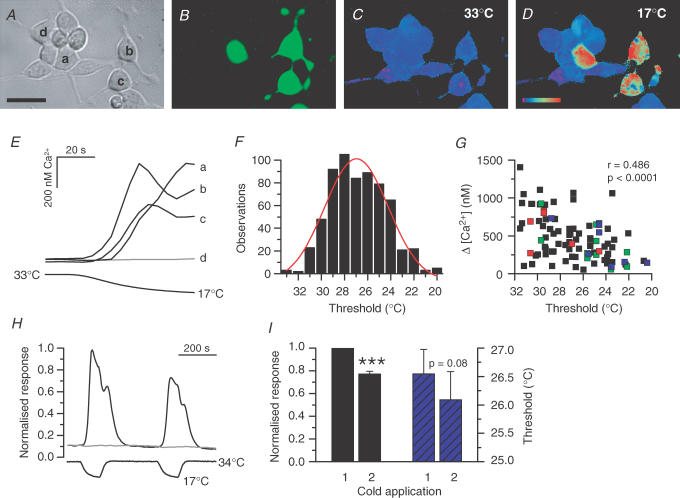

Figure 1. Properties of cold responses in TRPM8-expressing HEK293 cells.

Microscope images of optical field viewed with transmitted light (A), GFP fluorescence (excitation at 470 nm) (B), and Fura-2 fluorescence (ratiometric image from excitation at 340 and 380 nm) at 33°C (C) and 17°C (D). The calibration bar, 30 μm; colour coding, pink to red:, 0–880 nm Ca2+. E, calcium-imaging recording of cold-evoked responses in the three GFP-positive cells visualized above (a, b and c), exhibiting different apparent threshold temperatures. The GFP-negative cell (d) did not respond to cooling. F, histogram of apparent temperature thresholds in individual TRPM8-transfected HEK293 cells in control solution, when the temperature was lowered from 32—33°C: mean, 26.8 ± 0.1°C; n, 641; median, 27.0°C; range, 13°C. The red curve represents the Gaussian fit of the histogram. G, correlation between threshold temperature and calcium increase in 95 cells. The coloured squares indicate data from individual experiments. The statistical significance of the correlation coefficient is indicated with its two-tailed P value. H, calcium-imaging experiment of two subsequent cold applications in control solution. The intracellular Ca2+ response (upper trace) was normalized to the peak value obtained during the first cold application. The response in the GFP-negative cell, which did not respond to cooling, was normalized to the peak value of the GFP-positive cell. I, left: the desensitization of the second cold response averaged 23 ± 2% (n = 39, P < 0.001, Student's paired t test) compared to the first one. Right: the threshold temperature of the second cold response (26.1 ± 0.5°C) was not statistically different from the first one (26.5 ± 0.4°C; n = 35, P = 0.08, Student's paired t test).

Experimental protocols and interpretation of results

During calcium-imaging experiments, the effects of the antagonist compounds were investigated with a protocol, wherein a first cooling stimulus in control solution was followed by a second one in the presence of a blocking agent (see Fig. 2A and B). To account for possible desensitization of the response during subsequent cooling stimuli, the same protocol was carried out in the absence of antagonists (see Fig. 1H). The observed reduction of the second response peak in control solution was taken into account when quantifying the blocking effects of the antagonists by defining an expected maximum response (Max Response) for the second application:

| (1) |

where DS is the desensitization coefficient obtained with the double-pulse protocol. For the dose–inhibition curves, the block was thus obtained from:

| (2) |

where Responseblocker is the response in the presence of antagonist, and fitted to the Hill equation:

| (3) |

where Blockmax is the maximum block, IC50 is the concentration of half-maximal inhibition, c is the blocker concentration and n is the Hill coefficient. The protocol employed to study the effect of menthol on the cold sensitivity of TRPM8 was similar to above except that the baseline temperature of the experiments was adjusted to 39–45°C to reveal information about shifts in the response threshold.

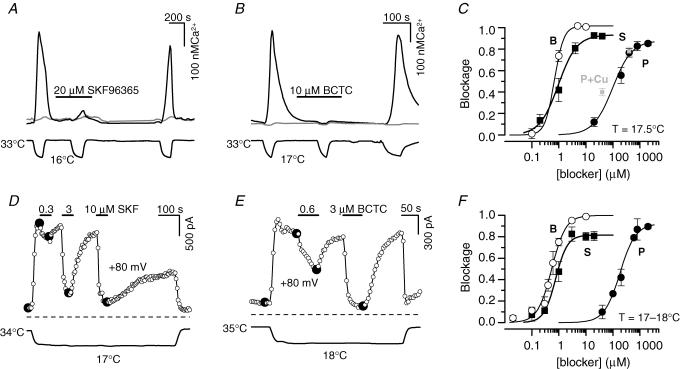

Figure 2. BCTC, SKF96365 and 1,10-phenanthroline block cold-evoked responses in TRPM8-expressing HEK293 cells.

A and B, experimental recordings of the effects of 20 μm SKF96365 and 10 μm BCTC on cold-evoked [Ca2+]i responses in TRPM8-transfected HEK293 cells. Upper trace shows intracellular Ca2+ and lower trace represents bath temperature. The unresponsive cells (grey traces) did not express GFP. C, dose–inhibition curves from calcium-imaging experiments of BCTC (B), SKF96365 (S) and 1,10-phenanthroline (P) at 17.5°C. The solid lines represent the fits to the Hill equation. The fits to the data yielded an IC50 of 0.68 ± 0.06 μm, Blockmax of 1.015 ± 0.009, and a Hill slope n of 2.5 ± 0.6 for BCTC (n = 4–18 cells); IC50 of 1.0 ± 0.2 μm, Blockmax of 0.93 ± 0.02, Hill slope n of 1.3 ± 0.3 for SKF96365 (n = 9–20 cells); IC50 of 100 ± 20 μm, Blockmax of 0.88 ± 0.03, Hill slope n of 1.2 ± 0.2 for 1,10-phenanthroline (n = 8–26 cells). For comparison, blockade obtained with 1,10-phenanthroline in the presence of Cu2+ are shown in grey (P:Cu2+ concentration ratio, 4: 1). D–E, time course of the block caused by various concentrations of SKF96365 and BCTC on cold-evoked whole-cell currents at +80 mV. The dashed lines indicate the zero current level; lower trace is bath temperature. F, dose–inhibition curves of BCTC (B), SKF96365 (S) and 1,10-phenanthroline (P) at temperature (T) of 17–18°C and holding potential of +80 mV. The solid lines represent the fits to the Hill equation, which yielded the parameters IC50 of 0.54 ± 0.04 μm, Blockmax of 1.00 ± 0.01, Hill slope n of 1.7 ± 0.2 (n = 2–8 cells) for BCTC; IC50 of 0.8 ± 0.1 μm, Blockmax of 0.82 ± 0.03, Hill slope n of 2.0 ± 0.4 (n = 2–5 cells) for SKF96365; IC50 of 180 ± 20 μm; Blockmax of 0.92 ± 0.03, Hill slope n of 1.5 ± 0.1 (n = 2–5 cells) for 1,10-phenanthroline (see text for definitions).

We also used whole-cell recordings of cold-induced currents to investigate the action of the different antagonists on TRPM8 channel activity. For dose–inhibition correlations, blocker compounds were briefly applied during an extended cold stimulus (see Fig. 2D and E). Current development was monitored with repetitive (0.2 Hz) injections of 1 s duration voltage ramps from −100 to +100 mV. The current block for the dose–inhibition curves was measured at +80 mV. To compare the effects of blockers on cold-evoked currents in individual cells, data were normalized to the response in control solution using the following equation:

| (4) |

where Responsecontrol is the response in the absence of blocker. Dose–inhibition data were fitted to the Hill equation presented in eqn (3). All current responses were corrected for leak currents, which were measured at 34°C to avoid interference from TRPM8, and temperature-corrected by a factor QΔT according to the following expression (Hille, 2001):

| (5) |

where ΔT is the difference between the baseline temperature (34°C) and the temperature of the cold stimulus. On the basis of control experiments in non-transfected HEK293 cells, the value of Q10 was fixed at 1.5, which is a reasonable value for the conductance of voltage-gated channels (Hille, 2001).

To provide information on shifts in the threshold temperatures, a protocol similar to that used for calcium imaging was used, where responses to cold in the presence and absence of antagonists were recorded at a holding potential of −60 mV. To estimate the shifts in the voltage dependence of activation of TRPM8 in HEK293 cells, current–voltage (I–V) relationships obtained from repetitive (0.2 Hz) voltage ramps (−100 to +200 mV, 525 ms duration) were fitted with a function that combines a linear conductance multiplied by a Boltzmann activation term (Nilius et al. 2006):

| (6) |

where g is the whole-cell conductance, Erev is the reversal potential, V1/2 is the potential for half maximal activation and s is the slope factor. The assumption of a linear conductance is based on the observation by Voets et al. (2004) that open TRPM8 channels exhibit an ohmic I–V dependence. For each cell, fitting was started by analysing a condition with strong channel activation; typically 100 μm menthol at 20°C. The value obtained for the parameter g at this condition was defined as gmax and used as a limit in the fitting of the remaining experimental conditions: g < gmax.Erev was fixed at a value close to the measured reversal potential of the current evoked by menthol and cooling. For trigeminal ganglion neurons, I–V relationships were obtained from voltage ramps (−100 to +200 mV) of 1.5 s duration.

Using voltage ramps instead of steps involves the possibility of not working under steady-state conditions. The benefit of the ramp protocol is, nevertheless, that it is more rapid, thus minimizing the time-dependent rundown of the current. We performed control experiments where we applied voltage ramps at two different speeds (525 ms and 5 s duration) in the same cells. No statistically significant difference was observed between the fitting parameters at the two speeds. However, we do not rule out the possibilty that the absolute values of the parameters may be slightly affected by non-stationary conditions.

Data analysis

Data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean. The apparent threshold temperatures were estimated as the first point at which the measured signal (F340/F380 or current) deviated by at least four times the standard deviation of its baseline. Data were analysed with WinASCD written by Dr Guy Droogmans (ftp://ftp.cc.kuleuven.ac.be/pub/droogmans/winascd.zip) and Origin 7.0 (OriginLab Corporation). Fitting was carried out with the Levenberg–Marquardt method implemented in Origin 7.0 software. In dose–response fits, the standard errors of the mean were used as weights. When comparing two means, statistical significance (P < 0.05) was assessed by Student's two-tailed t test. For multiple comparison of means obtained in the same subjects, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA was performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.00 for Windows (San Diego, CA, USA, http://www.graphpad.com).

Results

Co-transfection with TRPM8 and GFP

Analysis of 25 separate calcium-imaging experiments, with a total of 107 GFP-expressing HEK293 cells, revealed that 88% of these responded to a cold stimulus (Fig. 1A–D). As non-transfected HEK293 cells (Fig. 1B and D) or cells transfected with the empty vector pcINeo/IRES–GFP (data not shown) do not respond to cooling, this was taken as proof of the presence of functional TRPM8 channels in the cells. The time that the cells spent in culture between transfection and experiment seemed to influence the correlation between GFP fluorescence and TRPM8 expression. Cells that were used during days 1 and 2 (i.e. 20–58 h after transfection) exhibited the highest co-expression values: 94% of the GFP-positive cells were also TRPM8-positive at day 1 (n = 34) and 96% at day 2 (n = 55). The lowest percentage (72%, n = 18) was found in cells studied during day 3 (64–82 h) post transfection. A plausible explanation for this finding may be that by day 3, the amount of GFP in the cells reaches a toxic level (Liu et al. 1999).

Cold-evoked responses in TRPM8-transfected HEK293 cells

From electrophysiology experiments, we determined a mean apparent threshold temperature of TRPM8 in HEK293 cells in control solution of 27.6 ± 0.5°C (n = 19), when the temperature was lowered from a base value of 32–33°C at a holding potential of −60 mV. In the calcium-imaging experiments, the apparent threshold temperature was 26.8 ± 0.1°C (n = 641). The threshold distribution in the calcium-imaging experiments exhibited a range of 13°C and a median value of 27.0°C (see Fig. 1F). The wide range of observed thresholds cannot be attributed to experimental error, as cells in the same field exhibited largely different threshold temperatures (see Fig. 1E). The mean Ca2+ elevation was 480 ± 40 nm (n = 95). As seen in Fig. 1G, a low but statistically significant correlation could be established between response threshold and amplitude of Ca2+ increase, the trend being that large calcium responses are more likely to occur in cells with high threshold temperatures.

When two subsequent cooling stimuli were carried out, as shown in Fig. 1H, the amplitude of the second response was found to be 23 ± 2% smaller than the first one (n = 39, P < 0.001, Student's paired t test; Fig. 1I). This mean desensitization of the response was taken into consideration when estimating the blocking effects of drugs, by assigning a desensitization correction (DS, 0.77) to the expected response in eqn (1). Whereas DS affected the response amplitude, it did not affect the threshold temperatures of subsequent cold-evoked responses (Fig. 1I).

SKF96365, BCTC and 1,10-phenanthroline block cold-evoked responses in TRPM8-expressing HEK293 cells

SKF96365 is a non-specific blocker of various calcium-permeable channels, including both receptor-operated and voltage-gated types, as well as those activated by internal calcium store depletion (Merritt et al. 1990). At higher concentrations (IC50, ∼40 μm), SKF96365 has also been reported to block an inwardly rectifying K+ current in endothelial cells (Schwarz et al. 1994). In dorsal root ganglion neurons, a cold-activated current was reduced by almost 70% in the presence of 100 μm SKF96365 (Reid et al. 2002).

We tested the effects of SKF96365 on cold-evoked responses in TRPM8-transfected HEK293 cells. As shown in Fig. 2A, 20 μm SKF96365 produced a robust and reversible inhibition of cold-evoked [Ca2+]i elevation in transfected cells. To quantify the potency of SKF96365 as a TRPM8 channel antagonist, we constructed dose–inhibition curves (Fig. 2C) from the responses at 17.5°C: a temperature at which the average response in control solution had reached its maximum value. Hill fits to these data yielded an IC50 of 1.0 ± 0.2 μm. At the end of each experiment, the cells were left in control solution for 15 min to remove the accumulated antagonist. Washing out the effects of SKF96365 was concentration dependent and amounted to 56–85% of the initial signal, for decreasing concentration of the blocker.

In the whole-cell electrophysiology experiments, various concentrations of SKF96365 (0.1–20 μm) were applied during an extended cooling stimulus (Fig. 2D). Currents were evoked by consecutive voltage ramps from −100 to +100 mV, delivered every 5 s, and Icold at +80 mV was plotted versus time. SKF96365 produced a concentration-dependent, but incomplete inhibition of this current, as seen in Fig. 2D. This effect was highly reversible upon washing: the initial signal recovered by > 80% for concentrations below 10 μm, and > 70% for 10 and 20 μm SKF96365. Figure 2F shows the complete dose–response curve of block of cold-evoked currents by SKF96365 at +80 mV and 17–18°C. The solid line represents the fit to the Hill equation, which yielded an IC50 of 0.8 ± 0.1 μm.

BCTC was recently introduced as an orally bioavailable antagonist agent of the TRPV1 channel, with a high selectivity in an extensive radioligand screen against other ion channels (Valenzano et al. 2003). More recent studies demonstrate that BCTC also readily blocks menthol-evoked (Behrendt et al. 2004; Weil et al. 2005) and cold-evoked responses of TRPM8 (Madrid et al. 2006). We tried to establish BCTC as a reference compound of TRPM8 block, comparing its effects on TRPM8 with those of other drugs. A typical calcium-imaging recording is shown in Fig. 2B. The Hill fit (Fig. 2C) of the blockade at 17.5°C yielded an IC50 of 0.68 ± 0.06 μm and full block at high concentrations. The recovery of the initial signal after a 5 min washing period depended on the BCTC concentration used, varying between 21% and 63% for the highest and lowest concentrations tested. Whole-cell electrophysiology experiments (Fig. 2E), confirmed that BCTC potently blocks TRPM8-mediated cold responses at +80 mV with an IC50 of 0.54 ± 0.04 μm and Blockmax of 1.00 ± 0.01 (Fig. 2F).

Cu–Phe is an oxidizing agent capable of inducing formation of disulphide bridges between appropriately located thiol groups, and has been widely employed in studies of the gating motion of voltage-gated channels (Liu et al. 1996). The Cu–Phe complex is also an antagonist of the TRPV1 channel; however, in this case it acts as an open-channel blocker instead of inducing cysteine cross-linking (Tousova et al. 2004). Meanwhile, both the free 1,10-phenanthroline and its Cu–Phe complex are equally potent open-channel blockers of the human skeletal muscle Na+ channel (Popa & Lerche, 2006).

In our studies, the free 1,10-phenanthroline acted as an antagonist of the TRPM8-mediated cold-evoked responses in HEK293 cells. The dose–response data of 1,10-phenanthroline block from calcium-imaging and whole-cell electrophysiology experiments were fitted to the Hill equation (Fig. 2C and F), and yielded IC50 values of 100 ± 20 and 180 ± 20 μm, respectively. We subsequently investigated the inhibitory capacity of the Cu–Phe complex on cold-evoked TRPM8 responses. In the presence of 100 μm Cu2+ and 400 μm 1,10-phenanthroline, 78 ± 4% (n = 24) of the calcium response was blocked at 17.5°C (Fig. 2C, grey square), a value almost identical to that observed in the presence of 400 μm free 1,10-phenanthroline alone (77 ± 4%, n = 26, P = 0.83, Student's unpaired t test). Thus, in the case of TRPM8, complex formation with the divalent copper ion does not seem to be necessary for 1,10-phenanthroline antagonism. The inhibition in response to free and complexed 1,10-phenanthroline was reversible which strongly indicates that the mechanism of inhibition does not involve cross-linking of cysteines (Liu et al. 1996; Aziz et al. 2002).

Blockade of Icold by BCTC and SKF96365 is voltage dependent

The nature of the antagonism of cold-evoked currents of TRPM8 by BCTC and SKF96365 was studied in more detail with whole-cell electrophysiology. As seen in Fig. 3A and D, cooling of the control bath solution from around 35°C to 18°C activated a current characterized by a reversal potential near 0 mV and strong outward rectification, as reported before for TRPM8 currents (McKemy et al. 2002; Voets et al. 2004). The concentration-dependent inhibition of this current by SKF96365 and BCTC is clearly seen in the I–V plots. More detailed analysis of the I–V curves revealed that blockade of Icold by the two antagonists is voltage dependent. Figure 3B and E shows the blockade induced by concentrations around the IC50 of BCTC and SKF96365 over a wide range of potentials, demonstrating that Icold is strongly blocked at negative potentials by these submaximal concentrations of antagonist, while a significant fraction of the current remains at more positive potentials. The statistical significance of the observed differences in degree of block with potential was assessed using a one-way repeated-measures ANOVA test combined with a post test for a linear trend. The results (BCTC, P < 0.01 for one-way repeated-measures ANOVA and P < 0.001 for linear regression; SKF96365, P < 0.001 for both) indicate that the mean blockade at different potentials is statistically different, and that the voltage dependence of the block is not an artefact caused by random error.

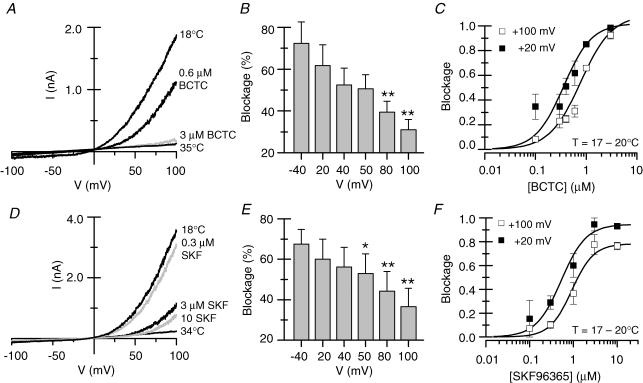

Figure 3. Inhibition of TRPM8 by BCTC and SKF96365 is voltage dependent.

A and D, current–voltage relationships of cold-evoked currents and the effects of various concentrations of BCTC and SKF96365. The antagonists were applied at a temperature of 18°C. The locations of the voltage ramps are marked with large, filled circles in Fig. 2D and E. B, the blockade by 0.6 μm BCTC analysed over various potentials. Dunnett's post hoc test in combination with one-way repeated-measures ANOVA (P < 0.01) was employed to assess statistical significance between the blockade at each of the studied potentials and at –40 mV (**P < 0.01). C, dose–inhibition curves of 0.6 μm BCTC at +20 and +100 mV. Whereas the maximum blockade was unaffected, the IC50 was increased with increasing depolarization. E, the blockade by 1 μm SKF96365 analysed over various potentials. Statistical significance was assessed with Dunnett's post hoc test in combination with one-way repeated-measures ANOVA (P < 0.001) between the blockade at each of the studied potentials and at –40 mV. F, dose–inhibition curves of SKF96365 at +20 and +100 mV. Note that both maximum blockade and IC50 varied as a function of potential.

The I–V data were further employed to construct dose–inhibition curves at different potentials. As the cold-evoked inward current was often very small, analysis at negative potentials was less accurate, and thus the potentials +20 and +100 mV were chosen for illustrative purposes. For BCTC, shown in Fig. 3C, the effect of depolarizing the membrane potential translates to a shift in the dose–inhibition curve towards larger antagonist concentrations. Accordingly, full blockade was reached at all studied potentials, with IC50 values between 0.36 ± 0.04 μm at +20 mV and 0.78 ± 0.08 μm at +100 mV. In the case of SKF96365 (Fig. 3F), together with the shift in the dose–inhibition curve (IC50, 0.5–0.9 μm), membrane depolarization appeared to be coupled to a decline in maximum effect of the antagonist.

The inhibition of the cold-evoked current by 1,10-phenanthroline was also voltage dependent (not shown), exhibiting weaker inhibition at more positive potentials. The effect was quantified for 600 μm 1,10-phenanthroline, which blocked 92 ± 2% of the cold-evoked current at +40 mV, and 70 ± 2% at +100 mV (P < 0.001, Student's paired t test, n = 3).

BCTC and SKF96365 shift the activation curve of TRPM8 towards more positive potentials

The voltage-dependent antagonism by BCTC and SKF96365, together with the fact that both compounds are electroneutral at pH 7.4, led us to think that they are not acting as typical pore blockers driven by the transmembrane voltage (Hille, 2001). Recently it was shown that low temperature and menthol activate TRPM8 channels by producing a shift in the voltage-dependence of activation towards more negative potentials (Voets et al. 2004; Brauchi et al. 2004). We hypothesized that the mechanism of inhibition exerted by the studied TRPM8 antagonists involved an opposite effect on the voltage dependence of activation (i.e. a shift in gating towards more depolarized potentials). Consequently, TRPM8 activation was probed with 525 ms duration voltage ramps from −100 to +200 mV in whole-cell voltage-clamp mode both in CR#1 HEK293 cells stably expressing rat TRPM8 channels (Brauchi et al. 2004) and in transiently transfected HEK293 cells (Fig. 4A, B, D and E).

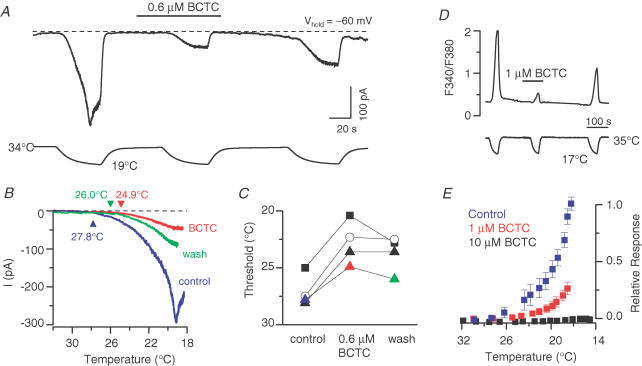

Figure 4. BCTC and SKF96365 shift the activation curve of TRPM8 towards more positive potentials.

A, time course of current development at +160, +80 and −80 mV in a CR#1 HEK293 cell under various experimental conditions. Voltage ramps (−100 to +200 mV) of 525 ms duration were delivered every 5 s and the current traces for the time points marked with filled dots are presented in B. The dashed line indicates the zero current level; lower trace is bath temperature. B, whole-cell ramp I–V relationships corresponding to the different conditions shown in A. The red lines, superimposed on each trace, represent the fit of the current to eqn (6). C, summary histogram of the effects of BCTC on the midpoint of voltage activation (V1/2) of TRPM8 channels (n = 3–22). The data are represented as shifts in V1/2 with respect to the value obtained for cold. Statistical significance was assessed with the unpaired t test and is indicated ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05. D, time course of the blockade caused by SKF96365 on cold-evoked whole-cell currents at +160 and +80 mV. Current traces for the time points marked with filled dots are presented in E. The dashed line indicates the zero current level; lower trace is bath temperature. E, whole-cell ramp I–V relationships corresponding to the experiment shown in D. The red lines represent the fits to eqn (6). F, shifts in V1/2 induced by 3 μm BCTC, 3 μm SKF96365 and 300 μm 1,10-phenanthroline with respect to the value in cold. The average values for V1/2 during cold application in control solution were 156 ± 7 mV (BCTC), 158 ± 6 mV (SKF96365) and 146 ± 5 mV (1,10-phenanthroline). Statistical significance was assessed with one-way ANOVA (P < 0.01) in combination with Dunnett's post hoc test using 3 μm BCTC as the reference, and is indicated **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05.

Figure 4A shows the effects of 3 μm BCTC on currents evoked by cold and/or menthol at −80, +80 and +160 mV. The I–V curves from the same experiment are shown in Fig. 4B. As can be seen, in this cell cooling to 20°C produced a clear augmentation of the outward current at depolarized potentials only, while co-application of the cold stimulus with 100 μm menthol also produced a potentiation of the inward current at negative potentials. Application of 3 μm BCTC in the continuous presence of both agonists (cold and menthol) produced an incomplete inhibition of outward currents but a full inhibition of inward currents. To estimate the midpoint of activation (V1/2), a measure of changes in channel gating, the ramp I–V data obtained in the presence and absence of antagonists were fitted (red lines in Fig. 4B) with eqn (6) described in the Methods, which consists of a Boltzmann activation term combined with a linear conductance. The assumption of a linear conductance was shown to be reasonable by Voets et al. (2004).

A summary of the mean values obtained for the fitting variables under different experimental conditions is shown in Table 1. As reported previously, cooling and menthol produced marked leftward shifts in V1/2 (Voets et al. 2004; Brauchi et al. 2004). By contrast, application of 3 μm BCTC produced a positive shift in V1/2 and a reduction in g but no apparent change in the slope factor s (P > 0.05 when comparing conditions with and without BCTC). For conditions of 33°C, 20°C, 100 μm menthol at 33°C, and 100 μm menthol at 20°C, application of 3 μm BCTC shifted V1/2 by 34 ± 9 mV (n = 6); 67 ± 11 mV (n = 8); 78 ± 6 mV (n = 21), and 97 ± 11 mV (n = 15), respectively (P < 0.05 for all shifts, paired t test). These data indicate that the inhibitory effects of BCTC increase under conditions of high open probability of the TRPM8 channel.

Table 1.

Summary of the effects of temperature, menthol and BCTC on TRPM8 activation in HEK293 cells

| Control 33°C | Cold 20°C | 100 μm menthol 33°C | Cold + 100 μm menthol | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no drug | 3 BCTC | no drug | 1 BCTC | 3 BCTC | no drug | 1 BCTC | 3 BCTC | no drug | 1 BCTC | 3 BCTC | |

| s (mV−1) | 36 ± 2 | 54 ± 8 | 35 ± 1 | 40 ± 3 | 45 ± 4* | 38 ± 2 | 33 ± 3 | 36 ± 1 | 40 ± 2 | 48 ± 5 | 41 ± 1 |

| g (nS) | 38 ± 3 | 25 ± 11 | 52 ± 5 | 48 ± 14 | 19 ± 6‡; | 78 ± 7 | 60 ± 10 | 43 ± 7†; | 86 ± 7 | 64 ± 19 | 56 ± 5†; |

| V1/2 (mV) | 215 ± 4 | 229 ± 11 | 153 ± 5 | 193 ± 19* | 223 ± 10‡; | 89 ± 6 | 112 ± 16 | 172 ± 7‡; | 58 ± 4 | 122 ± 33 | 153 ± 9‡; |

| n | 39 | 6 | 26 | 3 | 8 | 29 | 8 | 21 | 24 | 3 | 15 |

The absolute values of the parameters s, g and V1/2 obtained from the fits of the ramp (−100 to +200 mV) I–V curves to eqn (6) in the Methods. The data are given as means ±s.e.m. and are grouped according to the different experimental conditions (control or agonist) onto which BCTC was applied. To assess statistical significance, unpaired t test was performed between the parameters obtained in the absence (‘no drug’) and presence of BCTC for each antagonist condition, and significance indicated:

P < 0.05

P < 0.001

P < 0.001.

To better illustrate the bidirectional shifts in the voltage activation of TRPM8 induced by BCTC, menthol and temperature, we constructed a summary histogram (Fig. 4C) where the mean V1/2 values of the various experimental conditions are presented relative to the value obtained for cold in the same cells. As can be seen in Fig. 4C, cooling to 20°C alone produced a significantly smaller negative shift than applying 100 μm menthol at 33°C (P < 0.01, n = 12, paired t test). In the presence of both agonists, 3 μm BCTC completely cancelled the effect of 100 μm menthol and restored V1/2 to the value obtained in the presence of cold alone (P = 0.54, n = 14, paired t test). In summary, under the various experimental conditions (see also Table 1), the effect of 1–3 μm BCTC was to produce a significant positive shift in V1/2 with only a modest reduction in g, particularly at lower concentrations of antagonist.

We subsequently studied whether a similar effect on the voltage activation of TRPM8 was induced by SKF96365 and 1,10-phenanthroline. Figure 4D and E shows the time course of whole-cell current development and I–V data of a TRPM8-positive cell where 3 μm SKF96365 was applied during a cold stimulation. As summarized in Fig. 4F, application of 3 μm SKF96365 during cooling induced a positive shift on V1/2 that averaged 24 ± 3 mV (n = 6; P < 0.001, paired t test). For 300 μm 1,10-phenanthroline, the mean value of the shift was 35 ± 5 mV (n = 5, P < 0.01, paired t test).

The functional consequence of the bidirectional shift in channel gating is a displacement in the apparent temperature-response threshold of TRPM8-expressing cells

The observation that the antagonists and menthol shift the activation curve of TRPM8 in opposite directions prompted us to investigate whether the same holds true for the apparent response threshold during a temperature stimulus.

Figure 5A shows the whole-cell current (holding potential, −60 mV) in a TRPM8-expressing cell as the bath temperature was cooled in the absence and presence of 0.6 μm BCTC. Comparing the current responses during the cooling ramp (Fig. 5B), we found that the apparent response threshold was shifted by an average of −4.3 ± 0.5°C (P < 0.01, n = 4, paired t test). The shifts observed in four individual cells are shown in Fig. 5C. The effects of BCTC on apparent TRPM8 response thresholds obtained from calcium-imaging experiments (Fig. 5D) were analysed in terms of relative response curves (Fig. 5E). Briefly, for each cell, the relative response at a temperature T was calculated as the fluorescence response normalized to the expected maximum response of the cell (i.e. the response to cold in control solution corrected with the desensitization coefficient (eqn (1)). The relative responses of the individual cells (n = 16–19 for each condition) were averaged, yielding the curves seen in Fig. 5E. Whereas 10 μm BCTC produced a complete inhibition of the current, lower concentrations of the drug reduced the peak amplitude and shifted the response towards lower temperatures. The control curve was obtained in an identical manner from experiments where the second cooling application was also performed in the absence of drug; this confirmed that the observed shifts in the response curves is not an artefact of applying subsequent cooling applications.

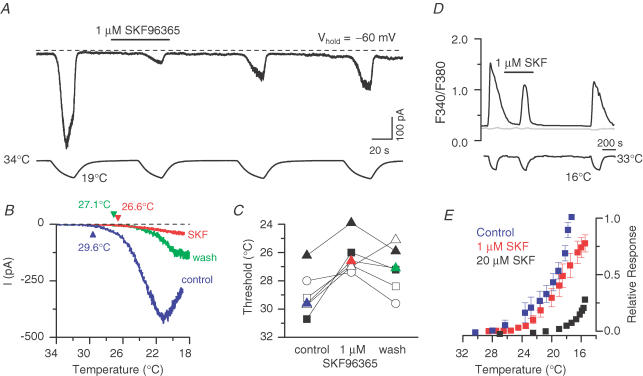

Figure 5. BCTC lowers the response-threshold temperature during cooling.

A, simultaneous recording of whole-cell membrane current (top trace) and bath temperature (bottom trace) during application of three consecutive cooling ramps to a TRPM8-transfected HEK293 cell (holding potential, −60 mV). Application of 0.6 μm BCTC produced a reversible reduction in Icold amplitude. The dashed line indicates the zero current level. B, close-up and superposition of the cold-evoked responses shown in A in the absence and presence of 0.6 μm BCTC. The current traces were corrected to yield a 0 pA baseline; holding potential, −60 mV. C, response-threshold temperatures of four cells during cold applications in control solution, 0.6 μm BCTC and after washing. The coloured symbols correspond to the cell in A and B. D, fluorescence ratiometric (F340/F380) calcium-imaging recording of cold-evoked responses in the absence and presence of 1 μm BCTC. E, relative response versus temperature curves constructed from cooling ramps in the presence of 1 and 10 μm BCTC. For each cell, the relative response at each temperature was calculated as the fluorescence response normalized to the expected maximum response of the cell, defined in eqn (1). The control curve was obtained in an identical manner from experiments where the second cooling application was also performed in the absence of drug. Each data point represents the average of 16–19 cells. For clarity, error bars are omitted where negligibly small.

For SKF96365 we found, similarly, that the apparent response threshold was shifted to lower temperature values in the presence of antagonist. From whole-cell electrophysiology experiments (Fig. 6A and B) we determined an average shift of −2.6 ± 0.5°C (P < 0.01, n = 6, paired t test) for 1 μm SKF96365. The shifts for six individual cells are shown in Fig. 6C. As observed for BCTC, SKF96365 shifted the relative response curves during cooling towards lower temperatures in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6D and E). However, whereas 10 μm BCTC was capable of completely blocking the responses evoked by cooling to 14°C (Fig. 5E), in the presence of 20 μm (Fig. 6E) or 40 μm (not shown) SKF96365, a fraction of the response remained when the cooling was continued below 20°C. Thus, the capacity of SKF93653 to modulate TRPM8 gating seems to be both weaker (requires higher antagonist concentration) and more limited (restricted threshold shift range) than that of BCTC.

Figure 6. SKF96365 shifts the response-threshold temperature towards lower values in a concentration-dependent manner.

A, simultaneous recording of whole-cell membrane current (top trace) and bath temperature (bottom trace) during application of four consecutive cooling ramps to a TRPM8-transfected HEK293 cell (holding potential, −60 mV). Application of 1 μm SKF96365 produced a reversible reduction in Icold amplitude. The dashed line indicates the zero current level. B, superimposed current–temperature relationships in control, in the presence of 1 μm SKF96365, and after washout of the drug. Same traces as in A. Note the marked shift in threshold temperature induced by SKF96365. The current traces were corrected to yield a 0 pA baseline; holding potential, −60 mV. C, response-threshold temperatures of six TPRM8-expressing HEK293 cells during cold applications in control solution, in 1 μm SKF96365 and after washout of the drug. The coloured symbols correspond to the cell in A and B. D, fluorescence ratiometric (F340/F380) calcium-imaging recording of cold-evoked responses in the absence and presence of 1 μm SKF96365. A TRPM8-negative cell in the same field is shown in grey. E, relative response–temperature curves constructed from cooling ramps in the presence of 1 and 20 μm SKF96365. Each data point represents the average of 9–16 cells. For clarity, error bars are omitted where negligibly small.

Expressing the average threshold-temperature shifts as divided by unit concentration, one obtains −7.2 and −2.6°C μm−1 for BCTC and SKF96365, respectively, yielding a ratio of potency of 2.8 in favour of BCTC. It is intriguing that by comparing the shifts in V1/2 induced by the two antagonists (8.1 and 22.4 mV μm−1), one obtains exactly the same ratio, suggesting that the two phenomena are strongly coupled.

These results indicate that, with regard to cold sensing, the main functional effect of the antagonists is a dose-dependent shift in the apparent temperature activation threshold of the cell.

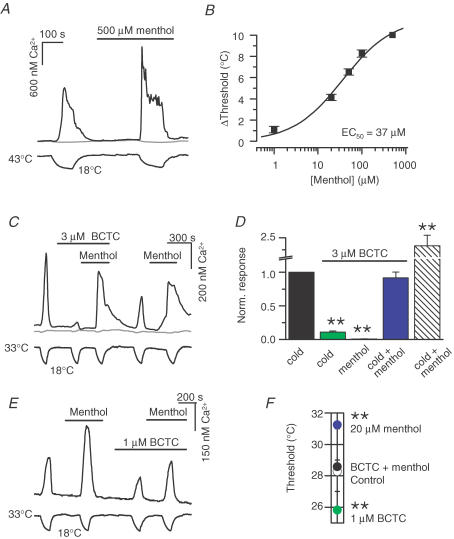

The modulation of cold-evoked responses of TRPM8-expressing cells by menthol and antagonists is additive

Considering the opposite shifts in activation curves and apparent temperature thresholds induced by menthol and the antagonists, we were curious to investigate the effects of joint applications of agonists (thermal and chemical) and antagonists on TRPM8 channel activity. Menthol-evoked responses of TRPM8 have previously been shown to be blocked by BCTC (Behrendt et al. 2004; Weil et al. 2005; Madrid et al. 2006). We confirmed the same to be true for SKF96365 (not shown), with 20 μm of the antagonist blocking 99.5 ± 3% of the calcium response evoked by 100 μm menthol (n = 12, P < 0.001, paired t test). To obtain quantitative information on the menthol-induced shifts in temperature sensitivity of TRPM8, we constructed a dose–threshold shift curve (Fig. 7A and B), which exhibited a maximum threshold shift of 11.6 ± 0.9°C and a half-maximum concentration of 37 ± 9 μm. Remarkably, this EC50 value is very similar to the dose-dependent shift in V1/2 produced by menthol (Voets et al. 2004). The cooling ramps in these experiments were initiated from 39–45°C to allow for the detection of the menthol-modified temperature thresholds in the absence of a baseline response (see Fig. 7A). It should be noted that the briefly applied higher baseline temperature did not modify per se the sensitivity of the channel to temperature changes. This was confirmed by an experiment carried out in control solution, where the thresholds to the first cold application (base temperature 32–33°C) and the second cold application (after 200 s of base temperature 39°C) were not statistically different (n = 5, P = 0.7, paired t test).

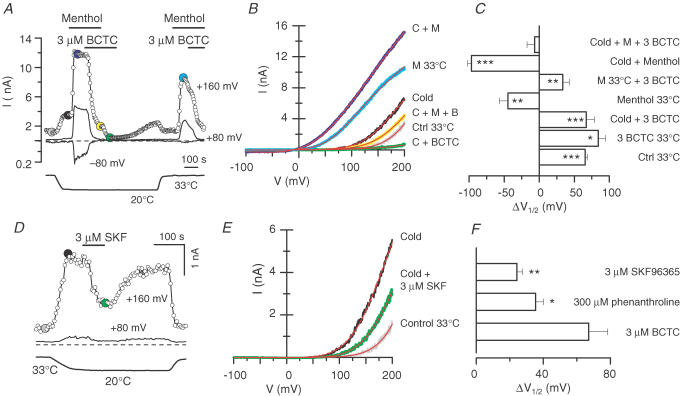

Figure 7. Bidirectional shifts of TRPM8 activity by chemical antagonists and menthol in TRPM8-transfected HEK293 cells.

A, time course of ratiometric [Ca2+]i response in a TRPM8-positive HEK293 cell (black trace) in the absence and presence of 500 μm menthol. The starting temperature was 43–45°C to prevent the ‘spontaneous’ response to menthol at the usual baseline temperature. The grey trace corresponds to a GFP-negative cell. B, correlation between menthol concentration and temperature threshold shift based on experiments shown in A (n = 11–19). The solid line is the fit to the Hill equation. C, experimental recording of the effect of 3 μm BCTC on [Ca2+]i responses to cold and/or 100 μm menthol. Upper trace is intracellular Ca2+ and lower trace is bath temperature. The unresponsive cell (grey trace) did not express GFP. D, summary histogram of effects of 3 μm BCTC on cold- and menthol-evoked changes in [Ca2+]i. Note that BCTC effectively blocks calcium responses to cold (86 ± 2% inhibition, P < 0.01) or 100 μm menthol (100% inhibition, P < 0.01), but not to a combination of the two agonists (92 ± 9% of control response, P > 0.05). Each response was normalized to the amplitude of the nearest preceding cold response in control solution; n = 22. E, experimental recording of the effects of 1 μm BCTC plus 20 μm menthol on cold-evoked responses of TRPM8. Upper trace is intracellular Ca2+ and lower trace is bath temperature. F, average response-threshold temperatures in control solution, 20 μm menthol, 1 μm BCTC and 1 μm BCTC + 20 μm menthol (n = 19). In all panels statistical significance was assessed with Dunnett's post hoc test in combination with one-way repeated-measures ANOVA (P < 0.001 for all) with respect to the response in control solution, and indicated ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05.

Figure 7C demonstrates the experimental calcium-imaging protocol where 3 μm BCTC was applied over stimuli of cold, 100 μm menthol and cold combined with menthol. During analysis, each response was normalized to the response to cold in control solution, yielding the graph shown in Fig. 7D. Although 3 μm BCTC was capable of nearly abolishing the response to cold, and all of the response to menthol at 33°C, the combination of the two agonists restored the response amplitude to the same level as observed for cold in the absence of chemical agents.

We subsequently searched our data for menthol and antagonist concentrations for which matching threshold temperature shifts, but in the opposite direction, had been observed during individual applications, to see whether these shifts could be cancelled out during the combined application of both agents. Figure 7E shows a calcium-imaging experiment, where the joint effects of 1 μm BCTC and 20 μm menthol on apparent response-threshold temperatures were investigated. Notably, analysis of the results (Fig. 7F) revealed that the individually observed shifts (i.e. the opposite shifts produced by menthol and BCTC) indeed cancel each other out when the compounds are co-applied during cooling. Another antagonist with similar cancelling effects when combined with 20 μm menthol was 4 μm SKF96365 (not shown). The fact that simple algebraic operations can explain the opposite effects of agonists (cold and menthol) and antagonists on the TRPM8 temperature-response threshold suggests that a common mechanistic principle underlies the actions of the various modulators.

Bidirectional modulation by menthol and blocking agents on cold-evoked responses are maintained in trigeminal thermoreceptors

We investigated whether similar bidirectional shifts in channel function can be observed in native cold thermoreceptors, the sensory neurons responsible for the transduction and coding of temperature signals in the peripheral nervous system (Hensel, 1981). Cold-sensitive trigeminal ganglion neurons were identified by calcium imaging as previously described (de la Pena et al. 2005). During rapid reductions in bath temperature from a baseline of 34°C to approximately 18°C, cold-sensitive neurons responded with an average [Ca2+]i elevation of 247 ± 44 nm (n = 20) exhibiting a mean apparent threshold of 30.2 ± 0.9°C with a range of 10°C. This threshold temperature is significantly higher than the one we obtained in TRPM8-expressing HEK293 cells (P < 0.001, Student's unpaired t test). All cold-sensitive neurons identified in this particular calcium-imaging screen were also activated by menthol, which suggests they all expressed endogenous TRPM8 channels. We note here that in a previous similar screen with a higher number of neurons, we also identified a cold-sensitive but menthol-insensitive population that represented ∼8% of the total number of cold-sensitive neurons (Madrid et al. 2006).

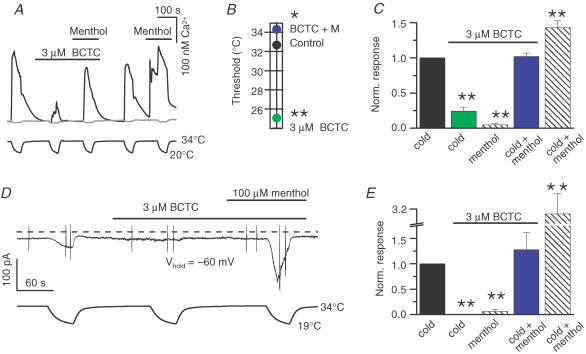

In these neurons, 3 μm BCTC strongly suppressed [Ca2+]i increases evoked by cold and completely abolished the responses to 100 μm menthol at 34°C (Fig. 8A and C). As was the case with recombinant TRPM8 channels, applying a cold stimulus in the presence of both menthol and BCTC provoked [Ca2+]i increases with very similar amplitude to the control response(change in [Ca2+]I, 262 ± 54 nm, P = 0.29, n = 20). As seen previously for heterologously expressed TRPM8, BCTC application shifted the apparent threshold temperatures of the cold-sensitive neurons towards lower values. In 10 neurons, the cold-induced response was completely abolished; in the other 10 cold-sensitive cells, the effect was partial and the threshold was shifted by an average of −7.6 ± 0.6°C (P < 0.01). In addition, co-application of menthol and cold completely reversed the negative shift in threshold temperature produced by BCTC, yielding a mean apparent threshold temperature of 31.9 ± 0.7°C. The mean shifts in threshold temperature for the 10 neurons in which some amount of response remained in the presence of BCTC are shown in Fig. 8B.

Figure 8. Menthol and the antagonists modulate cold-evoked responses in cold-sensitive trigeminal neurons.

A, calcium-imaging recording of the effect of 3 μm BCTC on responses to cold and/or 100 μm menthol. Upper trace is intracellular Ca2+ and lower trace is bath temperature. The grey trace shows the simultaneous response in a cold-insensitive neuron for comparison. Note the full inhibition of the menthol-evoked response at 34°C. B, average response-threshold temperatures of cold-sensitive trigeminal neurons in control solution, 3 μm BCTC and 3 μm BCTC + 100 μm menthol (n = 10). C, 3 μm BCTC effectively blocks calcium responses to cold or 100 μm menthol, but not to a combination of the two agonists. Each response was normalized to the nearest preceding cold response in control solution (n = 20). D, simultaneous recording of whole-cell membrane current (top trace) and bath temperature (bottom trace) during application of three consecutive cooling ramps, showing the effects of 3 μm BCTC and 100 μm menthol on cold responses in a cold-sensitive trigeminal neuron. The holding potential was −60 mV. The dashed line indicates the zero current level and the vertical lines mark clipped current responses to voltage ramps (see Figure 9). E, summary histogram of current responses at −60 mV from experiments shown in D (n = 3–8). In all panels statistical significance was assessed with Dunnett's post hoc test in combination with one-way repeated-measures ANOVA (P < 0.001 for all) with respect to the response in control solution, and indicated ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05.

Finally, the effects of agonists and antagonists on native Icold activation were also investigated. As shown in Fig. 8D, cooling produced a reversible inward current at a holding potential of −60 mV, which exhibited an apparent threshold of 30.9 ± 0.4°C (n = 29). Analysis of the current amplitudes under the various conditions confirmed the observations from the calcium-imaging experiments in both trigeminal neurons and TRPM8-expressing HEK293 cells: 3 μm BCTC effectively inhibited responses to separate applications of cold or 100 μm menthol, but co-application of the two agonists restored the response to the level of the control response (Fig. 8E).

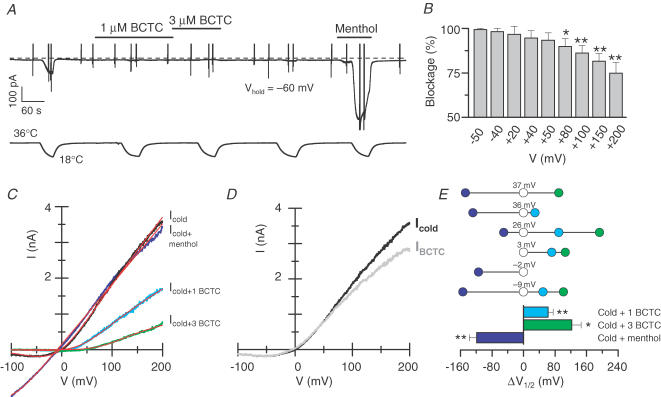

The effects of BCTC on the voltage activation of Icold were further studied with application of −100 to +200 mV ramps from a holding potential of −60 mV (Fig. 9A). An I–V plot of the cold-evoked current in the absence and presence of chemical modulators is shown in Fig. 9C. Icold displays strong outward rectification and reversal close to 0 mV (0.5 ± 1.0 mV; n = 8), which is similar to the properties of current conducted by TRPM8 (ITRPM8) in HEK293 cells. As observed for recombinant TRPM8 channels above, application of a cooling stimulus in the presence of BCTC produced an incomplete inhibition of outward currents but a full inhibition of inward currents in trigeminal neurons. This is illustrated in Fig. 9D, where IBCTC represents the part of Icold that was blocked by 3 μm BCTC (i.e. the difference between traces Icold and of the cold current of trigeminal neurons in the presence of 3μm BCTC (Icold+3 BCTC in Fig. 9C). Note that IBCTC only begins to deviate from Icold at potentials more positive than +70 mV, indicating a complete block by 3 μm BCTC below this value. A similar result was obtained by analysing the blockade of Icold in cold-sensitive trigeminal neurons by 3 μm BCTC over various potentials (Fig. 9B).

Figure 9. BCTC and menthol produce opposite shifts in the voltage activation curve ofIcold in cold-sensitive trigeminal neurons.

A, time course of current development at −60 mV in a cold-sensitive trigeminal neuron during cooling ramps. Voltage ramps (−100 to +200 mV) of 1500 ms duration were applied under the various experimental conditions (they appear as vertical bars in the current trace). B, blockade of Icold in seven cold-sensitive trigeminal neurons by 3 μm BCTC analysed over various membrane potentials. Dunnett's post hoc test in combination with one-way repeated-measures ANOVA (P < 0.001) was employed to assess statistical significance between the blockade at each of the studied potentials and at −50 mV. C, whole-cell ramp I–V relationships of the experiment shown in A at 18°C in the presence and absence of BCTC (1 and 3 μm) and 100 μm menthol. The red lines, superimposed on the recorded I–V relationships, represent the fits of the current to eqn (6). D, the grey trace (IBCTC) represents the part of Icold that was blocked by 3 μm BCTC (Icold−Icold+3 BCTC). Note that IBCTC only begins to deviate from Icold at potentials more positive than +70 mV, indicating a complete block by 3 μm BCTC below this value. E, effects of BCTC and menthol on the midpoint of voltage activation during cooling in six cold-sensitive trigeminal neurons. The data are represented as shifts in V1/2 with respect to the value obtained for cold (the absolute value for each neuron is indicated above the open symbol). Below a summary histogram of the average shifts in V1/2 with respect to cold (n = 4–6). Statistical significance was assessed with the unpaired t test and is indicated ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05.

To estimate V1/2, the ramp I–V data obtained in the presence and absence of antagonists were fitted (red lines in Fig. 9C) with eqn (6). A summary of the mean values obtained for the fitting variables under different experimental conditions is shown in Table 2. Comparing the values in Tables 1 and 2, one can see a notable difference between the mean value of V1/2 measured from native Icold and cold-induced ITRPM8 in transfected cells; V1/2 was significantly more negative in the former (15 versus 153 mV, P < 0.001, unpaired t test). Furthermore, despite the qualitatively similar effect of BCTC on the voltage activation of the cold current in TRPM8-expressing HEK293 cells and cold-sensitive trigeminal neurons, the magnitude of the shift in V1/2 induced by BCTC was significantly larger in the trigeminal neurons: 122 ± 24 (n = 4) versus 67 ± 11 mV (n = 8); P < 0.05 (unpaired t test).

Table 2.

Summary of the effects of menthol and BCTC on Icold activation in cold-sensitive trigeminal neurons

| Cold 20°C | Cold 20°C 1 μm BCTC | Cold 20°C 3 μm BCTC | Cold 20°C 100 μm menthol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| s (mV−1) | 40 ± 5 | 42 ± 5 | 46 ± 8 | 32 ± 9 |

| g (nS) | 19 ± 4 | 19 ± 5 | 5 ± 1* | 23 ± 4 |

| V1/2 (mV) | 15 ± 8 | 76 ± 14† | 137 ± 28* | −101 ± 23† |

| n | 6 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

The absolute values of the parameters s, g and V1/2 obtained from the fits of the ramp (−100 to +200 mV) I–V curves to eqn (6) in the Methods (see text for definitions). The data are given as means ±s.e.m. Statistical significance was assessed with Student's unpaired t test using cold as the reference condition, and is significance indicated:

P < 0.05

P < 0.01.

These results indicate that native cold-sensitive channels with similar biophysical properties to TRPM8 (e.g. similar reversal potential and rectification properties) are activated by temperature at more negative membrane potentials. The native channels are blocked by BCTC in a similar manner to recombinant TRPM8 in terms of amplitude, but the biophysical modulation (shifts in V1/2 and temperature threshold) underlying the inhibition is notably stronger in the trigeminal neurons.

Discussion

At present very little is known about the pharmacological and biophysical properties of TRPM8 channel antagonists (Desai & Clapham, 2005; Dhaka et al. 2006; Voets et al. 2007). This information is essential to better understand the role of TRPM8 channels in temperature transduction at peripheral thermoreceptors (Madrid et al. 2006).

In this study, we provide a thorough characterization of the responses of recombinant TRPM8 channels to their physiological stimulus, cold temperature, and describe in mechanistic terms the effects of substances that increase and decrease the temperature sensitivity of the channel. We identified a common modulatory action of three chemical antagonists (BCTC, SKF96365 and 1,10-phenanthroline) on TRPM8 function that involves marked shifts in their voltage-dependent gating. Furthermore, we describe important differences between the properties of recombinant TRPM8 channels and native currents in trigeminal cold thermoreceptors that underlie their high thermal sensitivity.

Cold-induced responses in TRPM8-expressing HEK293 cells and trigeminal neurons

In our experiments, rat TRPM8-transfected HEK293 cells responded to cooling with apparent threshold temperatures of 26.8°C and 27.6°C as measured by calcium imaging and electrophysiology, respectively. These values, although among the highest reported for heterologously expressed rodent TRPM8 (McKemy et al. 2002; Peier et al. 2002; Andersson et al. 2004), are clearly lower than observed for cold-sensitive trigeminal and dorsal root ganglion neurons (Reid et al. 2002; Viana et al. 2002; Thut et al. 2003; Madrid et al. 2006). Such differences suggest that the cellular environment (e.g. membrane lipid composition and presence of auxiliary subunits) may be an important factor in the modulation of TRPM8 function, and/or that other mechanisms of cold transduction are present in sensory neurons, making them more sensitive to temperature decreases (de la Pena et al. 2005).

BCTC is the most potent antagonist of cold-evoked responses in TRPM8 channels

Arranging the blockers from our study by their IC50 values yielded the following sequence of potency: BCTC > SKF96365 >> 1,10-phenanthroline, with the first two compounds exhibiting concentrations of half-maximum TRPM8 inhibition below or close to 1 μm. Comparison with previously reported values revealed that SKF96365 is a slightly more potent antagonist of TRPM8 than of other TRP channels (e.g. TRPC3 and TRPC6) studied to date (Zhu et al. 1998; Inoue et al. 2001). By contrast, SKF96365 was not an effective blocker of the epithelial calcium channel TRPV5 (Nilius et al. 2001).

Here, 1,10-phenanthroline was equally effective in blocking cold-evoked TRPM8 responses in the presence as in the absence of Cu2+. This finding is in contrast with a previous report on TRPV1, where heat-evoked currents were only blocked in the presence of the Cu–Phe complex (Tousova et al. 2004) suggesting a different mechanism of block for these two TRP channels.

BCTC produced full antagonism of cold-evoked TRPM8 activity in the temperature range studied, with similar IC50 values to those determined using menthol as the stimulus (Behrendt et al. 2004; Weil et al. 2005; Madrid et al. 2006). These IC50 values, although one to two orders of magnitude larger than observed for TRPV1 (Valenzano et al. 2003; Correll et al. 2004), make BCTC the most potent and most effective antagonists of TRPM8 channels to date.

In conclusion, although none of the blockers studied here are specific for TRPM8, the potent and reversible TRPM8 antagonism by BCTC and SKF96365 should make them useful for further functional characterization of thermoreceptor fibres and the role of TRPM8 channels in cold transduction.

Menthol and the blockers act as TRPM8 modulators in opposite directions

TRPM8 is a voltage-dependent channel (Voets et al. 2004; Brauchi et al. 2004; Rohacs et al. 2005). Low temperature, cooling agents (such as menthol) and the inositide phospholipids (such as phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2)) are known to shift the activation curve towards more physiological membrane potentials. However, the mechanisms and sites of action of these stimuli on the TRPM8 protein remain unclear. The voltage and temperature sensors are situated on separate structural domains (Brauchi et al. 2006). Furthermore, the menthol binding site and the cold sensor are structurally separate entities (Bandell et al. 2006). Whether the menthol molecule acts directly on the voltage sensor of TRPM8 or has a separate binding site on the protein remains to be resolved.

In the present work, we identify three new gating modifiers of TRPM8. On basis of the apparent voltage dependence of block and the shifts in the voltage activation of the channel towards more depolarized potentials, BCTC, SKF96365 and 1,10-phenanthroline should be considered negative allosteric modulators of the channel. In agreement with this view, recent reports on the effects of ethanol (albeit at a high concentration) on TRPM8 were also ascribed to a rightward shift in voltage-dependent gating (Benedikt et al. 2007). These agents may become useful tools in the ongoing quest for the molecular determinants of TRPM8 gating and regulation (Chuang et al. 2004; Nilius et al. 2005; Rohacs et al. 2005; Bandell et al. 2006). It is also of interest to find out whether the heat-sensitive TRPV1 channel can be modulated in a similar way by these chemical agents.

The main functional consequence of the dynamic voltage-dependent gating of TRPM8 is a shift in the apparent temperature activation threshold of the cell. Consequently, the studied antagonists exert an opposite effect to cooling and menthol on the thermosensitivity of the channel. Furthermore, the effects induced separately by menthol and the antagonists appear to be additive (i.e. they cancel each other during joint application of the compounds). The above findings raise the question of whether menthol and the antagonists studied here share the same site of action, or act through separate receptors. We find indications suggesting that the antagonists may be acting on different sites from which they exert their competitive, opposite effects on the voltage gating of TRPM8. Because the functional and biophysical effects of the antagonists on cold-evoked responses – shifts in apparent temperature thresholds and V1/2 – take place both in the absence and presence of menthol, and the antagonist-induced shifts in the voltage-dependent activation are in fact stronger during activation by menthol than by cold, it seems likely that the inhibitory effect is independent of the occupation of the menthol-binding site. This issue can only be completely settled with a direct analysis of ligand binding, with ad hoc designed radioactive probes.

The fact that none of the inhibitors acted as a pure pore blocker (i.e. reducing channel activity without affecting channel gating) indicates that some caution should be taken when interpreting the lack of inhibitory actions of these agents on cold-evoked responses at nerve terminals (Madrid et al. 2006): the negative modulatory effects on the native channel may be insufficient to prevent cold-evoked activity. However, when we compared the effects of BCTC on channel gating observed in TRPM8-expressing HEK293 cells and in cold-sensitive trigeminal neurons, we found that the opposite was true: the neurons were, in fact, more sensitive to modulation by BCTC than the HEK293 cells. Together with the fact that in the study by Madrid et al. (2006) the effects of menthol – a more potent agonist of recombinant TRPM8 channels than cold temperature – were fully suppressed at the nerve terminals, the new observations from this work argue for alternative explanations, such as the presence of additional, TRPM8-independent, cold sensors at nerve endings (Viana et al. 2002).

Native Icold channels have distinct properties

The bidirectional modulation of the voltage-dependent activation and the resulting shift in temperature threshold caused by menthol and antagonists is also conserved in cold-sensitive trigeminal neurons expressing native TRPM8 protein subunits. We found a remarkable difference in the V1/2 of TRPM8 activation between native and recombinant channels, with a much higher open probability at negative potentials in the former case. Thus, despite lower values of cold- and menthol-sensitive conductance in neurons (i.e. lower density of TRPM8 channels), their higher open probability gives rise to larger inward currents at physiological membrane potentials. In functional terms, this difference translates into a much higher apparent threshold temperature in native thermoreceptors compared to recombinant TRPM8 channels (see Supplementary Fig. 1). In both cases, response thresholds can be shifted bidirectionally by more than 15°C, directly illustrating the dynamic nature of the apparent temperature threshold of TRPM8 channels. Although our results were obtained with exogenous agents, it is very likely that endogenous modulators of the channel operate upon the same general principles, and in the process give rise to the wide range of threshold temperatures exhibited by recombinant TRPM8 channels in various expression systems (de la Pena et al. 2005) and cold-sensitive thermoreceptors (Reid et al. 2002; Viana et al. 2002; Thut et al. 2003). One such endogenous modulator could be the membrane lipid PIP2, which is known to potentiate the activity of TRPM8 (Liu & Qin, 2005; Rohacs et al. 2005; Benedikt et al. 2007) and that of other TRP channels (Hardie, 2003; Nilius et al. 2006). Notably, PIP2 modulates TRPM8 by shifting the V1/2 of activation of the channels (Rohacs et al. 2005). Additional factors that may contribute to the response plasticity of thermoreceptors are changes in TRPM8 channel density, modulation of TRPM8 by intracellular Ca2+ levels (McKemy et al. 2002; Reid et al. 2002; Rohacs et al. 2005), phosphorylation status of TRPM8 (Premkumar et al. 2005; Abe et al. 2006) and the variable expression of potassium channels acting as temperature-dependent excitability brakes (Viana et al. 2002).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank E. Quintero, A. Miralles and A. Pérez Vegara for excellent technical assistance. The TRPM8 cDNA and pcINeo-IRES-GFP vector were generous gifts from Drs David Julius and Jan Eggermont, respectively. The HEK293 CR#1 cell line was supplied by Dr Ramón Latorre. The authors thank Diego Muñoz for performing some preliminary experiments concerning effects of BCTC. During the course of this work A.m. was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Foreign affairs (MAE)/Spanish Agency for International Cooperation (AECI), the Osk Huttunen Foundation and the Academy of Finland (grant no. 107866), R.m. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship of the Spanish Fundación Marcelino Botín and V.M and M.V. by predoctoral fellowships from the Generalitat Valenciana. The work was also supported by funds from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science: projects SAF2004-01011 to F.V. and BFI2002-03788 to C.B.

Supplementary material

Online supplemental material for this paper can be accessed at:

http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2006.123059/DC1 and http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/suppl/10.1113/jphysiol.2006.123059

References

- Abe J, Hosokawa H, Sawada Y, Matsumura K, Kobayashi S. Ca2+-dependent PKC activation mediates menthol-induced desensitization of transient receptor potential M8. Neurosci Lett. 2006;397:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson DA, Chase HW, Bevan S. TRPM8 activation by menthol, icilin, and cold is differentially modulated by intracellular pH. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5364–5369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0890-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz QH, Partridge CJ, Munsey TS, Sivaprasadarao A. Depolarization induces intersubunit cross-linking in a S4 cysteine mutant of the Shaker potassium channel. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42719–42725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207258200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandell M, Dubin AE, Petrus MJ, Orth A, Mathur J, Hwang SW, Patapoutian A. High-throughput random mutagenesis screen reveals TRPM8 residues specifically required for activation by menthol. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:493–500. doi: 10.1038/nn1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista DM, Jordt SE, Nikai T, Tsuruda PR, Read AJ, Poblete J, Yamoah EN, Basbaum AI, Julius D. TRPA1 mediates the inflammatory actions of environmental irritants and proalgesic agents. Cell. 2006;124:1269–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt HJ, Germann T, Gillen C, Hatt H, Jostock R. Characterization of the mouse cold-menthol receptor TRPM8 and vanilloid receptor type-1 VR1 using a fluorometric imaging plate reader (FLIPR) assay. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:737–745. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedikt J, Teisinger J, Vyklicky L, Vlachova V. Ethanol inhibits cold-menthol receptor TRPM8 by modulating its interaction with membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J Neurochem. 2007;100:211–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauchi S, Orio P, Latorre R. Clues to understanding cold sensation: thermodynamics and electrophysiological analysis of the cold receptor TRPM8. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15494–15499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406773101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauchi S, Orta G, Salazar M, Rosenmann E, Latorre R. A hot-sensing cold receptor: C-terminal domain determines thermosensation in transient receptor potential channels. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4835–4840. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5080-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI, Julius D. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 2000;288:306–313. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang HH, Neuhausser WM, Julius D. The super-cooling agent icilin reveals a mechanism of coincidence detection by a temperature-sensitive TRP channel. Neuron. 2004;43:859–869. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE. TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature. 2003;426:517–524. doi: 10.1038/nature02196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CC, Phelps PT, Anthes JC, Umland S, Greenfeder S. Cloning and pharmacological characterization of mouse TRPV1. Neurosci Lett. 2004;370:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Pena E, Malkia A, Cabedo H, Belmonte C, Viana F. The contribution of TRPM8 channels to cold sensing in mammalian neurones. J Physiol. 2005;567:415–426. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai BN, Clapham DE. TRP channels and mice deficient in TRP channels. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:11–18. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1429-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaka A, Viswanath V, Patapoutian A. TRP ion channels and temperature sensation. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:135–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleig A, Penner R. The TRPM ion channel subfamily: molecular, biophysical and functional features. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:633–639. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Martinez C, Humet M, Planells-Cases R, Gomis A, Caprini M, de la Viana FPE, et al. Attenuation of thermal nociception and hyperalgesia by VR1 blockers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2374–2379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022285899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie RC. Regulation of TRP channels via lipid second messengers. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:735–759. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]