Abstract

In various types of cells mechanical stimulation of the plasma membrane activates phospholipase C (PLC). However, the regulation of ion channels via mechanosensitive degradation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) is not known yet. The mouse B cells express large conductance background K+ channels (LKbg) that are inhibited by PIP2. In inside-out patch clamp studies, the application of MgATP (1 mm) also inhibited LKbg due to the generation of PIP2 by phosphoinositide (PI)-kinases. In the presence of MgATP, membrane stretch induced by negative pipette pressure activated LKbg, which was antagonized by PIP2 (> 1 μm) or higher concentration of MgATP (5 mm). The inhibition by PIP2 was partially reversible. However, the application of methyl-β-cyclodextrin, a cholesterol scavenger disrupting lipid rafts, induced the full recovery of LKbg activity and facilitated the activation by stretch. In cell-attached patches, LKbg were activated by hypotonic swelling of B cells as well as by negative pressure. The mechano-activation of LKbg was blocked by U73122, a PLC inhibitor. Neither actin depolymerization nor the inhibition of lipid phosphatase blocked the mechanical effects. Direct stimulation of PLC by m-3M3FBS or by cross-linking IgM-type B cell receptors activated LKbg. Western blot analysis and confocal microscopy showed that the hypotonic swelling of WEHI-231 induces tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ2 and PIP2 hydrolysis of plasma membrane. The time dependence of PIP2 hydrolysis and LKbg activation were similar. The presence of LKbg and their stretch sensitivity were also proven in fresh isolated mice splenic B cells. From the above results, we propose a novel mechanism of stretch-dependent ion channel activation, namely, that the degradation of PIP2 caused by stretch-activated PLC releases LKbg from the tonic inhibition by PIP2.

Ion channels play critical roles in immunological responses. Although the most widely known players are Ca2+-permeable channels (Gallo et al. 2006), K+ channels provide the electrical driving force required for Ca2+ influx, cell volume regulation, and for apoptotic volume decrease (Beeton & Chandy, 2005). B cells are the principal cellular mediators of specific humoral immune response to infection. In a mouse B cell line (WEHI-231), we previously reported novel voltage-independent, large conductance background-type, K+ (LKbg) channels that are inhibited by phosphatidyl inositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). While LKbg was originally named BKbg (Nam et al. 2004), the acronym was changed to LKbg here to prevent confusion with the calcium-activated K+ channel (BKCa, maxi-K). LKbg channels show low activity in the intact cell membrane while their activity increases spontaneously after excising the membrane (inside-out (i-o) configuration). In i-o patches, LKbg channels are reversibly inhibited by applying MgATP to the cytoplasmic side, and the inhibition was found to be blocked by wortmannin, an inhibitor of phosphoinositide (PI)-kinase. Thus, it has been suggested that the molecular systems that regulate PIP2 levels are tightly associated with LKbg channels (Nam et al. 2004).

PIP2 is increasingly being recognized as a key physiological regulator of ion channel/transporters (Hilgemann et al. 2001; Horowitz et al. 2005; Suh & Hille, 2005). While most PIP2-sensitive ion channels are positively regulated, LKbg channels are inhibited by PIP2 along with TRPV1 and cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channels (Hilgemann et al. 2001; Suh & Hille, 2005). In spite of the conspicuous large conductance (∼300 pS), LKbg-like channels with PIP2 sensitivity have not yet been found in other types of cells, and the molecular identity is still unknown.

Although LKbg were originally termed ‘background’ K+ channels due to their voltage independence, their activity in the intact resting B cells is very low, which is most likely due to the PIP2 generated from the phosphorylation of phosphoinositides (Nam et al. 2004). Therefore, in pilot studies, we explored the activating conditions for LKbg channels. In these trials we found that mechanical stimulation by negative pressure of patch pipette or osmotic swelling of B cells reversibly activates LKbg channels. It has been recently reported that osmotic swelling and shear stress activate tyrosine kinase (Syk) in DT40 B cells (Miah et al. 2004; Qin et al. 1997), and elevate [Ca2+]i in mouse B cells by activating phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ) and non-selective cation channels (Liu et al. 2005; Zhu et al. 2005).

The PLC-mediated hydrolysis of PIP2 by membrane receptor activation is a widely observed regulatory mechanism of PIP2-sensitive ion channels (Suh & Hille, 2005). Considering that membrane stretch is also an activating condition for PLC (Moore et al. 2002; Ruwhof et al. 2001; Zhu et al. 2005; Liu et al. 2005), ion channels regulated by PIP2 might be affected by membrane stretch in a PLC-dependent manner. However, no study has been performed to investigate whether stretch-dependent PLC activation regulates the PIP2-sensitive ion channels. Since cells are exposed to various levels of mechanical stimuli, the elucidation of any such signalling mechanism would provide an intriguing insight into ion channel regulation. In the present study, we propose that the mechanosensitive activation of LKbg channels are mediated by PLC-dependent hydrolysis of PIP2.

Methods

Cells

WEHI-231 cells were grown in 25 mm Hepes RPMI 1640 media (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, USA), 50 μm 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco) at 37°C in 20% O2–5% CO2. Mouse primary B cells were prepared from the spleens of 6-week-old C57BL/6 mice. The animals in this study were procured, maintained, and used in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Seoul National University and Sungkyunkwan University. Mice were first deeply anaesthetized using 100% CO2 in an induction chamber. Following deep anaesthesia, mice were quickly killed by cervical dislocation, and the spleens removed to a small container filled with chilled PBS solution supplemented with 2% (v/v) fetal bovine serum. Spleens were dissociated into a single cell suspension, and B cells were isolated using a Spin-Sep B cell enrichment kit (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). Isolated cells were more than 95% B220-positive by flowcytometric analysis using a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). Isolated splenic B cells were kept in RPMI 1640 culture medium until used, which was within 5 h of isolation.

Electrophysiology

Cells were transferred into a bath mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (IX-70, Olympus, Osaka, Japan). The bath (approximately 0.15 ml) was superfused at 5 ml min−1 and voltage clamp experiments were performed at room temperature (22–25°C). Patch pipettes with a free-tip resistance of about 2.5 MΩ were connected to the head stage of a patch-clamp amplifier (Axopatch-1D, Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). pCLAMP software v.9.2 and Digidata-1322A (Axon) were used to acquire data and apply command pulses. Single channel activities were recorded at 10 kHz in cell-attached (c-a) and inside-out (i-o) configurations. Voltage and current data were low-pass filtered at 2 kHz. Current traces were stored and analysed using Clampfit v.9.2 and Origin v.7.0 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA). Data were analysed to obtain amplitude histograms and total channel activities (npo) where n and po are the observed levels of channel opening and the open probability, respectively. Since the total number of channels (N) varied for patches, a normalized open probability (Po=npo/N) was calculated for patch to patch comparisons. The total numbers of LKbg (N) were confirmed for each experiment by equilibrating i–o patches with MgATP-free solution. Data are represented as means ±s.e.m. Student's t test was used to determine significance at the 0.05 level. In Fig. 8A, one-way ANOVA (Bonferroni) with post hoc comparison was performed.

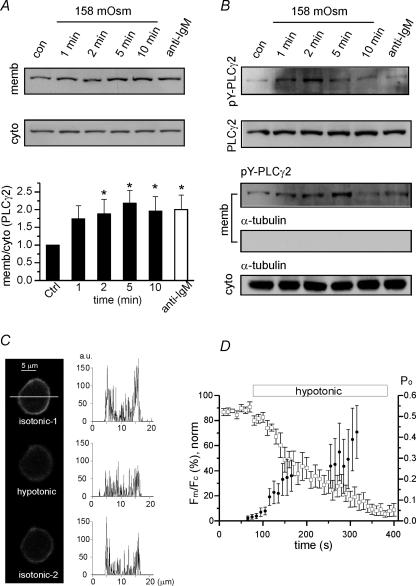

Figure 8. Activation of PLCγ2 and PIP2 hydrolysis by hypotonic swelling of WEHI-231 cells.

A, Western blot analysis of membrane and cytosolic fractions. Increased density ratios (membrane/cytoplasmic) indicate the membrane translocation of PLCγ2. In the lower panel, the ratios obtained under different periods of hypotonicity (158 mosmol kg−1) were normalized to control ratio (n = 5). The density ratio was also increased by B cell receptor (BCR)-ligation (n = 6, open column, anti-IgM Ab 5 μg ml−1, 2 min). *P < 0.05 tested by ANOVA with post hoc comparison (Bonferroni). B, increased tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ2 (pY-PLCγ2) by hypotonic swelling in total cell lysates (upper panel) and membrane fractions (lower panel). Upper panel: anti-PLCγ2 immunoprecipitates from whole-cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-pY-PLCγ2 Ab (top) and anti-PLCγ2 Ab (bottom). Lower panel: Western blotting of membrane fractions with anti-pY-PLCγ2 Ab (top) and anti-α-tubulin Ab (middle). C, representative confocal images of EGFP-PH expressed in WEHI-231 cells in control (upper), hypotonic conditions (158 mosmol kg−1, 2 min, middle), and reverse to isotonic control (290 mosmol kg−1, 3 min, lower). The fluorescence intensity along the horizontal axis (white bar) and the amplitude histograms (right column; a.u., arbitrary units). D, summary of the time-dependent translocation of the fluorescence from membrane (Fm) to cytosol (Fc) under hypotonic conditions (n = 7, □). For each cell, the minimum and maximum ratios (Rmin, Rmax) were obtained and used for the calculation of normalized ratio (Fm/Fc,norm, left vertical axis). Fm/Fc,norm= 100 × (R−Rmin)/(Rmax−Rmin). In the same panel, the time-dependent increase of LKbg channel activity (Po, right vertical axis) were also obtained by hypotonic swelling in c-a patches and the mean values are plotted together (n = 5–13, •). Note that the Po values between 175 and 250 s were omitted to prevent confusion with Fm/Fc.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

WEHI-231 cells were stimulated with hypotonic solution (158 mosmol kg−1; 10 mm Hepes, 80 mm KCl, pH 7.4) for various times. Cells were then harvested and suspended in homogenization buffer (20 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, 5 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 5 mm EGTA, 1 mm phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 10 μg ml−1 leupeptin, 10 mm 2-glycerophosphate, 3 mm Na3VO4, 50 mm NaF), and lysed using a 22-gauge needle. Nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 800 g for 5 min, and supernatants were separated by centrifugation at 30,000 g for 30 min into membrane (pellet) and cytoplasmic (supernatant) fractions. An equal amount of protein from each fraction was resolved by SDS–8% PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-PLCγ2 antibody (Cell Signalling Technologies, MA, USA) followed by HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Upstate Biotech, VA, USA). The intensities of protein bands were quantified using Multi Gauge software (Fuji Film, Japan) and data are expressed as membrane PLCγ2 signal/cytoplasmic PLCγ2 signal ratios. Membrane fractions were immunoprecipitated using anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (Upstate Biotech) overnight at 4°C, and then to protein G agarose for 2 h at 4°C. The samples were then immunoblotted as described above, and the membrane was stripped for 30 min at 50°C in stripping buffer (60 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 100 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS) and re-probed with anti-α-tubulin. When indicated, whole-cell lysates were immunoprecipitated without the subcellular fractionation procedure.

Confocal microscopy of WEHI-231 cells transfected with enhanced green fluorescent protein-coupled plextrin–homology domain of PLCδ1 (PH-EGFP)

WEHI-231 cells were transiently transfected with PH-EGFP (0.5 mg ml−1 from Dr Dong Min Shin, Yonsei University College of Dentistry, Seoul, Korea) using Nucleofector (Amaxa GmbH, Cologne, Germany) according to the manufacturer's manual. Laser scanning confocal microscopy (Olympus, FlowView TM 300, Olympus, Japan) was applied to visualize PH-EGFP (excitation 488 nm) in the periphery of cells under isotonic normal Tyrode solution (290 mosmol kg−1) and hypotonic (174 mosmol kg−1) conditions. Hypotonic solution was made by simple dilution of normal Tyrode solution with distilled water because the removal of sucrose induced optical artifacts. The obtained images were analysed using Igor (Wavematrix, Lake Oswego, OR, USA), public domain software ImageJ (Wayne Rasband, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) and Origin 6.1 (OriginLab Corp.). A specific cross-section at a constant vertical position was chosen for each cell that was analysed.

Experimental solutions and drugs

The pipette solution used for cell-attached (c-a) and inside out (i-o) patch clamps, and the bath solution for c–a contained (mm): 145 KCl, 1 EGTA and 10 Hepes at a pH of 7.4 (titrated with KOH). The bath solution for i-o patch clamps contained (mm): 145 KCl, 1 EGTA, and 10 Hepes at a pH of 7.2 (titrated with KOH). Fluoride-vanadate cocktail (FV solution), an inhibitor of lipid phosphatases, contained (mm): 5 NaF, 0.5 Na3VO4, 140 KCl, 1 EGTA, 10 Hepes at a pH of 7.2 (titrated with KOH). PIP2 was initially purchased as a chloroform solution. The chloroform was evaporated off under a stream of N2 to leave PIP2 residue. Recording solution was mixed with this residue and then sonicated for > 60 min on ice in the dark. PIP2 was purchased from Avanti (Alabaster, AL, USA). XY-14 ([1,1-difluoro-3,4-bis(oleoyloxy)butyl] phosphonate (sodium salt)) was purchased from Echelon (Salt Lake City, UT, USA), and all other chemicals and drugs were purchased from Sigma.

Plasma membrane stretching

Membranes were usually stretched by applying a negative pressure to a patch electrode. Actual pressures applied were calibrated and are presented as mmHg. In some experiments, membrane stretch was achieved by the hypotonic swelling of cells. For this purpose, the concentration of KCl in the bath solution was reduced to 80 mm and the total osmolality was controlled by adding sucrose, except in the confocal microscopy experiment (see above).

Results

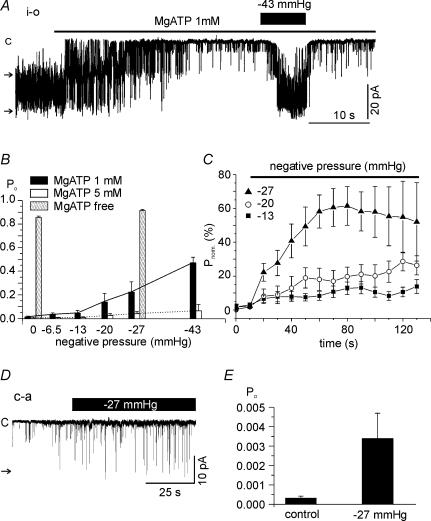

In the i-o configuration, a spontaneous single channel current with an amplitude of close to 20 pA was observed at a holding voltage of −60 mV in about 50% of 850 trials. With symmetrical concentrations of K+ in the pipette and bath solution, the approximate unitary conductance was 320–340 pS. In each experiment, the reversible inhibition of LKbg channels by applying MgATP to the cytoplasmic side was confirmed to identify LKbg channels, as described in our previous study (Nam et al. 2004). With 1 mm MgATP on the cytoplasmic side, membrane stretch by the negative pipette pressure reversibly increased the normalized open probability (Po) of LKbg channels in a pressure-dependent manner (Fig. 1A and B). At 5 mm MgATP, the stretch-sensitivity of LKbg channels was largely suppressed (Fig. 1B), but without MgATP, Po was 0.854 ± 0.01284 and the application of a negative pressure (−27 mmHg) increased Po slightly to 0.914 ± 0.0098 (n = 6). The time dependence of activation (Fig. 1C) showed that quasi-steady-state activation takes about 60 s at −27 mmHg. At lower levels of stretch, the LKbg channel activity increased continuously during the time analysed here. Although higher levels of negative pressure (e.g. −43 mmHg) induced faster activation (Fig. 1A), they were not analysed for the sustained stretch due to the instability of patch membrane. For cell-attached (c-a) patches, the small Po of LKbg channels was increased more than 10-fold (0.00031 ± 0.00012 to 0.00338 ± 0.00131, n = 26) by applying −27 mmHg of negative pressure for 20 s (Fig. 1D and E). The low activity of LKbg channels recorded in the c-a condition was similar to those recorded under i-o conditions with 5 mm MgATP.

Figure 1. Effects of membrane stretch on LKbg channel activity in inside-out (i-o) and cell-attached (c-a) patches.

A, for i-o patches, negative pressure was applied through a pipette after confirming inhibition of LKbg channels by MgATP (1 mm). Throughout the figures, the letter ‘c’ and horizontal arrows indicate the closed and open levels of LKbg channels, respectively. B, summary of normalized open probability (Po) measured at various negative pressures and different MgATP concentrations. C, time course of the increase in Po induced by membrane stretch. Mean values of normalized Po (100 ×Po/Po,max (%); Po,max was obtained under MgATP-free conditions) were plotted every 10 s under continuous negative pipette pressure; −13 (n = 11, ▪), −20 (n = 12, ○) and −27 mmHg (n = 13, ▴). D and E, a representative trace of c-a recording and summary of Po responses to negative pressure (−27 mmHg).

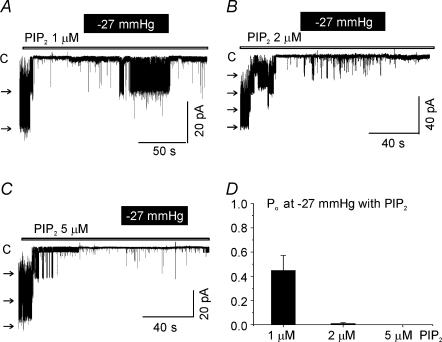

The stretch-induced activation of LKbg channels was reversible. However, after a sustained stretch (> 10 min), the channel activity became non-reversible or only partially reversible in 14 out of 55 patches (Fig. 2A and B). The permanently active LKbg channels in the presence of MgATP were still inhibited by the addition of PIP2 or phosphatidylinositol 4′-monophosphate (PI4P) (Fig. 1E and F). Unlike the potent inhibitory action of PIP2 alone (Fig. 3), the inhibition by PI4P (2 μm) required MgATP (Fig. 2C). Thus, it was supposed that the key substrates for the generation of PIP2, i.e. phosphoinositides, might have been lost or metabolized during stretch of the plasma membrane. Thus, the mechanosensitivity was examined in the presence of exogenous PIP2. A weak activation of LKbg channels by stretch was observed under the relatively low concentration of PIP2 (1 μm) by membrane stretch (−27 mmHg). However, at higher concentrations, the mechanosensitive activation was almost completely blocked (Fig. 3). These results suggested that membrane stretch somehow lowers the concentration of PIP2 in the plasma membrane, which relieves LKbg channels from the tonic inhibition by PIP2.

Figure 2. Irreversible activation of LKbg channels by chronic stretch and PIP2-dependent inhibition.

Representative traces of i-o recording under symmetrical K+ conditions. Time breaks with corresponding durations are indicated in the traces. A and B, by chronic stretch (−20 mmHg, 20 min), the activity of LKbg channels remained increased after relieving the negative pressure in the presence of MgATP. In this state, the addition of PIP2 or PIP (PI4P) inhibited LKbg channels. C, maximum LKbg channel activity was confirmed by excising a membrane patch in the absence of MgATP. The application of PI4P alone did not inhibit LKbg channels, whereas the co-application with MgATP abolished LKbg channel activity.

Figure 3. Weak effects of membrane stretch on LKbg channels under the direct inhibition by PIP2.

A–C, representative traces of i-o recording obtained at different PIP2 concentrations (1, 2 and 5 μm). D, summary of normalized open probabilities (Po) measured under the constant negative pressure (−27 mmHg) at different PIP2 concentrations (n = 3–5).

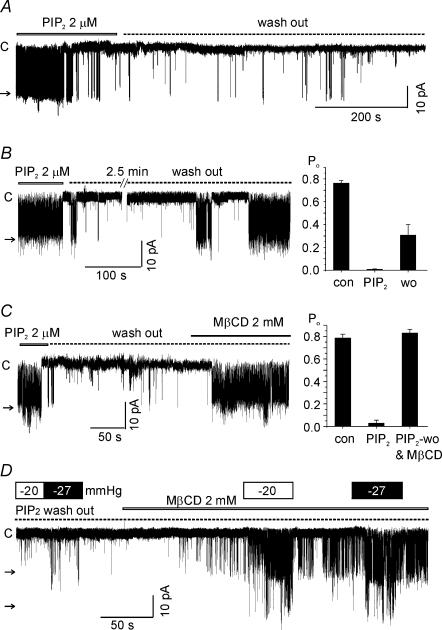

Unlike the effect of MgATP, the inhibition by PIP2 was not spontaneously reversed by washout after a prolonged application (> 1 min after confirming the inhibition of LKbg channels, Fig. 4A). To accomplish a partial recovery from the PIP2 effect, an early washout as soon as confirming the inhibitory effect (< 20 s) was necessary (Fig. 4B). According to the literature PIP2 is concentrated at the inner leaflets of lipid rafts defined as cholesterol- and sphingolipid-rich membrane microdomains (Edidin, 2003; Rodgers et al. 2005). Thus, we tested whether the integrity of lipid raft is crucial for the highly potent and irreversible inhibition of LKbg by PIP2. The application of methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD, 2 mm), a cholesterol scavenger disrupting lipid rafts (Kilsdonk et al. 1995), significantly facilitated the recovery of LKbg channels from the inhibition by PIP2 (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, recovery from PIP2-induced inhibition of LKbg channels by MβCD was prominently accelerated by a combined membrane stretch (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. Effects of MβCD and membrane stretch on recovery from the PIP2-induced inhibition of LKbg channels.

A, by a sustained application of PIP2 (e.g. > 1 min after confirming the inhibition of channels), the LKbg channel activity was not recovered by washout of PIP2 up to 20 min. B, an immediate and prolonged washout of PIP2 (< 20 s after confirming the inhibition) induced a partial recovery of LKbg channel activity. The summarized results are shown as a bar graph (n = 9, right panel). C, recovery of LKbg channels from inhibition by PIP2 was facilitated by adding MβCD (2 mm). Right panel, summary of the mean Po (n = 6). D, membrane stretch (−20 or −27 mmHg) combined with MβCD also facilitated LKbg channel recovery from the previous application of 2 μm PIP2 (dotted line, PIP2 washout). Similar results were obtained in three more cases. All the above experiments were i-o recordings.

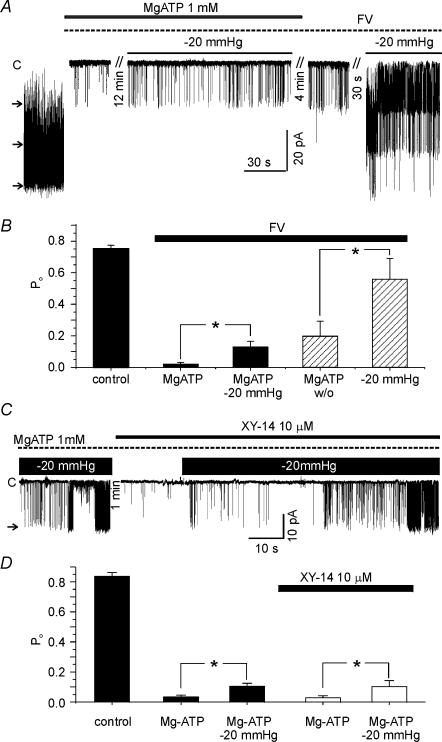

From the above results, we hypothesized that PIP2 in the plasma membrane is decreased by stretch, which would occur via activation of either lipid phosphatase (LPP) or phospholipase C (PLC). To inhibit LPP, a cocktail of fluoride and vanadate (FV solution, see Methods) is widely used (Zhang et al. 1995; Huang et al. 1998). The presence of FV solution did not block the stretch-induced activation of LKbg channels (Fig. 5A and B). Interestingly, the pretreatment with FV solution hampered the recovery of LKbg channels from MgATP-induced inhibition, and the full recovery was attained by membrane stretch (hatched bars in Fig. 5B). This result suggested that dephosphorylation by LPP might be involved in the recovery from MgATP-induced inhibition, and that the membrane stretch circumvented the LPP inhibition. We also tested XY-14, a recently described LPP inhibitor (Smyth et al. 2003). Pretreatment with 10 μm XY-14 did not inhibit the stretch-induced activation of LKbg (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. No significant effect of lipid phosphatase inhibitors on the stretch-induced activation of LKbg channels.

A, after confirming the inhibition of LKbg channels by MgATP (1 mm) in the i-o recording, a cocktail of 10 mm fluoride and 0.5 mm vanadate was applied (FV, dotted line). The membrane stretch (−20 mmHg) increased LKbg channel activity in the presence of FV (n = 9). The recovery from MgATP-induced inhibition was incomplete in the presence of FV whereas the combined stretch of membrane facilitated the recovery of LKbg channel activity (n = 6). B, summary of the above experiments shown as bar graphs. The data of hatched bars were obtained in the absence of MgATP. C, pretreatment with XY-14 (10 μm) did not block the stretch-induced activation of LKbg channels. D, summary of the above experiments shown as bar graphs (n = 6).

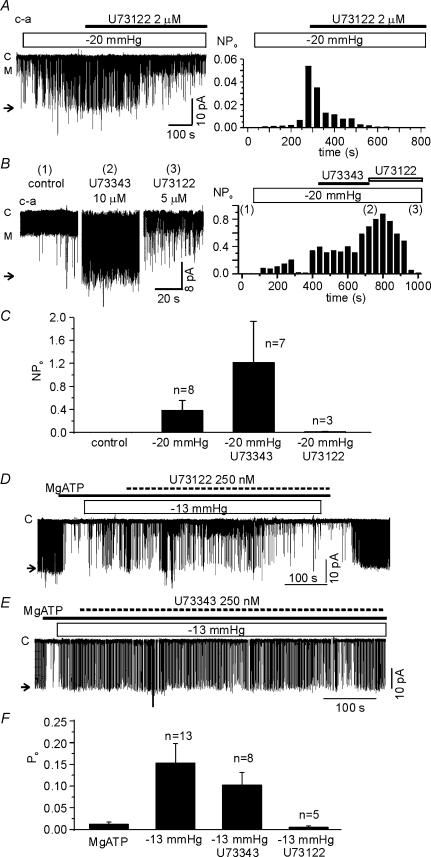

To investigate the role of PLC, U73122 (an inhibitor of PLC) and its negative analogue, U73343, were used. Under c-a conditions, 2 μm U73122 was applied after confirming the activation of LKbg channels by applying negative pressure (−20 mmHg). The stretch-dependent activation of LKbg channels was slowly reversed by U73122, whereas the inactive analogue U73343 (10 μm) had no effect (Fig. 6A and B). Moreover, the effect of U73122 appeared specific to the stretch-dependent activation of LKbg because another type of ion channel with a smaller conductance was unaffected by U73122 (indicated by ‘M’ in Fig. 6A). Under i-o conditions, for unknown reason(s), the combined application of 2 μm U73122 and negative pressure made the patch membranes highly unstable. Therefore, the concentration of U73122 and U73343 was lowered to 0.25 μm, and was applied in the early phase of membrane stretch (Fig. 6C and D). U73122 almost completely suppressed the LKbg channel activity under the sustained negative pressure (−13 mmHg). U73343 showed a weak inhibitory effect, which was, however, much smaller than the effect of U73122. LKbg channels were activated not only by the local stretch using patch pipettes but also by the hypotonic swelling of cells under c-a conditions (Fig. 7). The osmolality of bath solution was controlled by adding or removing sucrose to prevent changes in ionic concentration. The activity of LKbg channels was slowly increased by switching to hypotonic bath solution (158 mosmol kg−1), which was blocked by pretreatment with U73122 but not by U73343 (Fig. 7B–D).

Figure 6. Suppression of the stretch-induced activation of LKbg channels by the PLC inhibitor, U73122.

Effects of U73122 and its negative analogue U73343 were tested in c-a (A–C) and i-o (D–F) configurations. A and B, in the c-a condition, the stretch-induced activation of LKbg channels was slowly reversed by treatment with U73122, but not by its negative analogue U73343. The letter ‘M’ indicates the open level of another type of channel with medium conductance. Right panels are histograms of LKbg channel activity (NPo) reflecting the time-dependent changes. C, summary of the effects of U73122 and U73343 in the c-a patches. The larger activity in the presence of U73343 was due to prolonged stretch to confirm the negative effects of U73343. D, in the i-o recording, the application of U73122 (0.25 μm, 10 min) slowly reversed the stretch-induced activation of LKbg channels (n = 8). E, the prolonged application of U73343 induced a partial reverse of the stretch-induced LKbg channel activation (n = 5). F, summary of the effects of U73122 and U73343 in the i-o patches.

Figure 7. Activation of LKbg channels by hypotonic swelling and its inhibition by U73122.

A, in c-a configuration, the osmolality of the bath solution was changed as indicated in the figure. The letter ‘M’ indicates the open level of another type of channel with medium conductance. B and C, representative traces in the presence of U73122 or U73343. D, summary of the above results. After confirming the hypotonic activation of LKbg channels (158 mosmol kg−1, 2–3 min, n = 11), U73122 (4 μm, n = 6) or U73343 (10 μm, n = 5) was applied for an additional period (5–10 min). The larger activity in the presence of U73343 was due to longer treatment with hypotonic condition than the initial control.

PLCγ2 is known as a major PLC type in B cells (Hempel & DeFranco, 1991; Kim et al. 2004). Western blot analysis showed that the hypotonic swelling (158 mosmol kg−1) induces the membrane translocation of PLCγ2 and tyrosine phosphorylation. Also, the stimulation of membrane IgM-type B cell receptors by cross-linking with antibodies (BCR-ligation) induced similar responses (Fig. 8A and B). After swelling, tyrosine-phosphorylated PLCγ2 (pY-PLCγ2) was highly detected in membrane fractions and in whole-cell lysates. It is notable that an appreciable amount of PLCγ2 and pY-PLCγ2 in the membrane fraction were also detected in the control condition (Fig. 8A and B).

To confirm the hydrolysis of PIP2 by membrane stretch, EGFP-PH-expressing WEHI-231 cells were treated with hypotonic solution (158 mosmol kg−1) and visualized with confocal microscopy. Representative images of the WEHI-231 cell are shown with the histogram of fluorescence intensity along the horizontal axis (Fig. 8C).

In the control condition, fluorescence signal was shown along the plasma membrane which was largely decreased within 2 min of hypotonic swelling. The decreased fluorescence was recovered by perfusion with isotonic solution. In the confocal fluorescence images, the peripheral fluorescence (the amplitudes within peak ± 1 μm) was integrated along the membrane and regarded as membrane fluorescence (Fm). The fluorescence intensity of inner cytosol was also integrated (Fc). The averaged time-dependent changes of fluorescence ratio (Fm/Fc) under the hypotonic conditions demonstrate that it took approximately 100 s for the half-decrease of Fm/Fc (Fig. 8D). Such time dependency was comparable with the mean activation of LKbg channels by hypotonic swelling (Fig. 8D, filled circles).

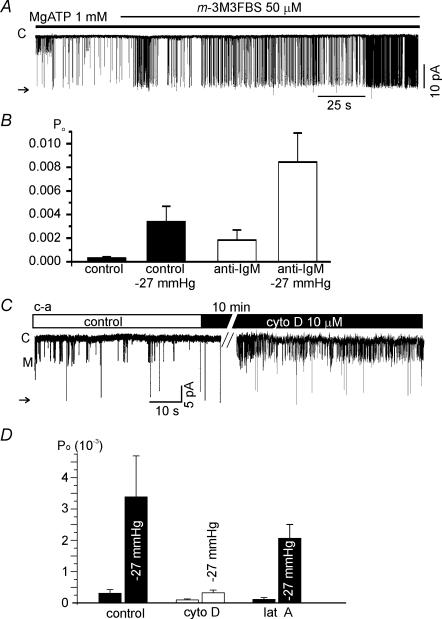

To directly stimulate membrane-bound PLC, m-3M3FBS (a chemical activator of PLC (Bae et al. 2003; Horowitz et al. 2005), was applied to i-o patches after confirming the inhibition of LKbg channels by MgATP. The addition of m-3M3FBS was found to activate LKbg channels (n = 4, Fig. 9A), whereas its negative control analogue, o-3M3FBS, had no effect (n = 3, data not shown). We also tested whether the stimulation of WEHI-231 cells by BCR-ligation modified LKbg channel activity. In the c-a recording of control WEHI-231 cells the Po of LKbg channels was very low (0.00031 ± 0.00012) as mentioned above (Fig. 1D). The Po was increased 11-fold by applying negative pressure (−27 mmHg, 15 s). After chronic BCR-ligation (2.5 μg ml−1 anti-IgM Ab, > 8 h), the basal Po of LKbg channels increased to 0.00183 ± 0.00087, and the same negative pressure further increased the Po to 0.00844 ± 0.00244 (n = 26, Fig. 9B).

Figure 9. Effects of PLC activation and actin depolymerizers on the activity of LKbg channels.

A, a representative trace of i-o recording. The application of m-3M3FBS (50 μm) slowly activated LKbg channels in the presence of MgATP (1 mm). B, summary of the effects of BCR-ligation on LKbg channel activity recorded in the c-a configuration with or without negative pressure (−27 mmHg). C, the acute effect of cytochalasin D (cyto D, 10 μm, 10 min) on the c-a patch. Note that the activity of the medium conductance channel (level M) was increased whereas LKbg was unaffected. D, summary of the chronic effect of cyto D (5 μm, 10 h, n = 10) or of latrunculin A (lat A, 5 μm, 10 h, n = 12) on LKbg channels and their activation by stretch (−27 mmHg).

The role of actin cytoskeleton in the mechanosensitive regulation of LKbg channels was investigated in c-a conditions. The application of 10 μm cytochalasin D (cyto D) for 10 min did not affect the activities of LKbg channels (Fig. 9C). Interestingly, another type of channel with smaller conductance (marked as ‘M’, Fig. 9C) was activated by the short treatment with cyto D, but was not investigated during this study. For a more complete disruption of the actin cytoskeleton, WEHI-231 cells were chronically treated with cyto D (5 μm, 90–120 min) or latrunculin A (lat A, 5 μm, 60–120 min). These treatments did not block the stretch activation of LKbg in c-a patch (Fig. 9D). However, for an unknown reason the overall activity of LKbg channels appeared to decrease after chronic treatment with cyto D but not with lat A (Fig. 9D).

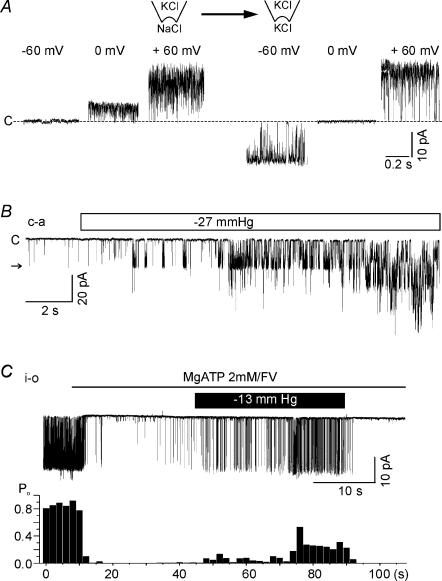

Finally, LKbg channel expression and its stretch sensitivity were also examined in freshly isolated splenic B cells. In the c-a condition using a KCl (145 mm) pipette solution, single-channel currents of large amplitude (ca 20 pA at −60 mV) were observed (21 patches out of 106 trials). In i-o patches, outward current was completely abolished by replacing K+ with isomolar Na+, thus indicating K+ selectivity (Fig. 10A). Like LKbg channels in WEHI-231 cells, Po was initially low but gradually increased on applying negative pressure to membranes (Fig. 8B). The activity of LKbg channels in splenic B cells was also reduced by MgATP (2 mm) on the cytoplasmic side of i-o patches, and was increased by the application of negative pressure through the pipette (−13 mmHg, Fig. 8C).

Figure 10. Functional expression of LKbg channels and their stretch-sensitive activation in mouse splenic B cells.

A, a representative i-o patch experiment demonstrating the K+ selectivity of channels. Large conductance channel activity (20 pA at −60 mV) was completely abolished by replacing K+ with Na+ on the cytoplasmic side. B, in c-a patches, multiple LKbg channels were slowly activated by negative pressure (−27 mmHg). C, in i-o patches, LKbg channel activities were suppressed by MgATP (2 mm), and this was partly reversed by applying negative pressure through the pipette (−13 mmHg).

Discussion

This study shows the mechanosensitive regulation of LKbg in WEHI-231 and freshly isolated splenic B cells of mice. Several hypotheses have been initially proposed to explain the mechanism of the stretch-dependent activation of the PIP2-sensitive LKbg channel: (1) conformation changes of LKbg caused by lateral tension, (2) transmission of force by cytoskeletal structures, (3) stretch-sensitive lipid phosphatases, and (4) stretch-sensitive PLC.

For the first hypothesis, the negligible effect of stretch in the presence of PIP2 (> 2 μm, Fig. 2) suggests that lateral tension per se does not play a key role. In the present study, lipid-derived agents affecting membrane fluidity or thickness were not tested because of concerns that those agents might unavoidably change the local concentration of PIP2 or the integrity of PIP2-rich microdomains. Actually, agents like MβCD were found to induce the activation of LKbg channels, which was supposedly due to the dispersions of PIP2-rich lipid rafts. In relation to the second hypothesis, many types of mechanosensitive channels are affected by cytoskeletal integrity (Hamil & Martinac, 2001; Cho et al. 2002). The cytoskeleton hypothesis is an intriguing idea since PIP2, the key modulator of LKbg channels, provides an anchoring site for actin filaments (Yin & Janmey, 2003). However, in the present study, response to stretch was not blocked by cyto D or lat A (Fig. 9).

TREK2, a cloned mechano-gated background K+ channel, is positively regulated by PIP2, and the electrical charge-dependent interaction between C-terminal peptide and PIP2 in the inner leaflet was proposed as a mechanism of mechanosensitivity (Chemin et al. 2005). In contrast with the positive modulation of TREK2 by PIP2, the stretch sensitivity of LKbg channels was potently abolished by PIP2 (> 2 μm), suggesting that the mechanosensitivity of LKbg channels is dependent on an indirect pathway different from TREK2. A schematic hypothesis was that membrane stretch tilted the equilibrium of PIP2 metabolism to the hydrolytic or dephosphorylating direction (the third and fourth hypotheses), which was drastically reversed by exogenous PIP2. The effects of U73122 and lipid phosphatase inhibitors on the mechano-activation of LKbg channels more specifically indicate the involvement of PLC.

Interestingly, chronic stretching (> 10 min) of excised patches induced the partially irreversible activation of LKbg channels, though this was fully inhibited by combined treatment with PI4P and MgATP (Fig. 2). Since PI4P alone did not inhibit LKbg channels, this suggested that chronic membrane stretching had actually depleted the PI pool through the hydrolysis of PIP2. Under the osmotic stretch of WEHI-231 cells, a substantial decrease of plasmalemmal PIP2 occurred with time courses similar to the activation of LKbg channels (Figs 1 and 8). Therefore, the most likely scenario appears to be that membrane stretch activates PLC, decreases local PIP2, which in turn releases LKbg channels from tonic inhibition by PIP2 (see our schematic model in the online Supplemental material). Although the activation of LKbg channels by PLC-activating agonists increased LKbg channel activity (Fig. 9), we do not show here that such agonists circumvent the LKbg channel activation by osmotic swelling due to their low potency. Further investigation of potent agonists linked with PLC is required to further validate the last hypothesis of the mechanosenstive PLC pathway.

Mechanosensitive PLC activation has been shown in several cell types (Missiaen et al. 1996; Ruwhof et al. 2001; Moore et al. 2002; Zhu et al. 2005). A novel suggestion from our study is that the stretch-dependent PLC activation can also regulate ion channels via changing the level of PIP2. The stretch effects in i-o patches suggest that putative mechanosensitive PLC molecules might be associated with the plasma membrane. In fact, a substantial amount of PLCγ2 was consistently observed in the membrane fraction of untreated WEHI-231 cells (Fig. 8).

Although the local stretch of patch membrane by suction could not be directly compared with the hypotonic inflation of cells, the positive effects on LKbg channels and blocking by PLC inhibitor (U73122) was similarly observed. Also, the hypotonic swelling increased membrane translocation and phosphorylation of PLCγ2. The similar time-dependent changes of PIP2 in the plasma membrane and the activation of LKbg channels (Fig. 8D) further supports the hypothesis that mechanosensitive PLCs play a key role at the whole-cell level as well as the localized stretch. However, since the recorded membrane patches are held by the micropipette, it was questioned how the channels are activated by general swelling of cells. Considering the widespread decrease of plasmalemmal PIP2 by hyposmotic conditions, we guess that the PIP2 in the relatively small patch membrane could be diluted (e.g. lateral diffusion through the membrane inner leaflet). Since the local concentration and movement of PIP2 is still a highly complicated and controversial theme (McLaughlin et al. 2002; Cho et al. 2005), further investigation is required to understand this result.

The c-a recording after BCR-ligation showed the increased activity of LKbg channels and proportional augmentation of stretch effects (Fig. 9). This suggests that the mechanosensitive regulation of K+ channels might have more implication when combined with immunological stimuli. Recent studies by Freedman's group have also demonstrated the phosphorylation of PLCγ and the release of IP3 by hypotonic swelling in the murine splenic B cells (Liu et al. 2005). Moreover, according to the literature, signalling from PLCγ2 in murine B cells leads to the activation of non-selective cation channels (NCS) via an arachidonic acid-dependent signalling pathway (Zhu et al. 2005). Taken together, the activation of LKbg channels and plausible membrane hyperpolarization might provide an electrical driving force for Ca2+ influx via NSC and/or store-operated Ca2+ channels, which might be amplified by mechanical stimuli. The activity of LKbg channels in intact B cells (c-a condition) was considerably lower than the maximum activity observed in i-o patches, which could be due to a relatively high concentration of ATP or some unknown intrinsic factors in the intact cytoplasm. In this respect, a substantial increase in LKbg channel activity in the intact B cells might be induced if the local concentration of ATP is lowered under metabolic inhibition or by the formation of long filopodial projections lacking mitochondria. In B cells, the stimulation of B cell receptors induces the formation of long filopodial projections, called membrane nanotubes (Gupta & DeFranco, 2003; Onfelt et al. 2004). Such conditions might also provide higher sensitivity to mechanical stress originating from the flow of plasma in vivo. To support such speculation, however, the molecular identity and immunohistochemical localization of LKbg channels in the subcellular domain are required.

In conclusion, we propose that the local degradation of PIP2 is accelerated by membrane stretch, which also releases LKbg channels from MgATP-dependent inhibition. As mentioned above, the membrane stretch- and cell volume-dependent PLC activation is being recognized in various types of cells. Although the molecular identification of the LKbg channels and the mechanisms of PLC activation remained to be elucidated, the regulation of PIP2-sensitive ion channels through the mechano-chemical signalling pathway provides a novel mechanism to be pursued for understanding cellular functions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R01-2005-000-10231-0 from the Korea Science & Engineering Foundation and BK21 grant from Ministry of Education and Human Resources.

Supplemental material

Online supplemental material for this paper can be accessed at:

http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2007.128413/DC1 and

http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/suppl/10.1113/jphysiol.2007.128413

References

- Bae YS, Lee TG, Park JC, Hur JH, Kim Y, Heo K, Kwak JY, Suh PG, Ryu SH. Identification of a compound that directly stimulates phospholipase C activity. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1043–1050. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.5.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeton C, Chandy KG. Potassium channels, memory T cells and multiple sclerosis. Neuroscientist. 2005;11:550–562. doi: 10.1177/1073858405278016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemin J, Patel AJ, Duprat F, Lauritzen I, Lazdunski M, Honore E. A phospholipid sensor controls mechanogating of the K+ channel TREK-1. EMBO J. 2005;24:44–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Kim YA, Yoon J-Y, Lee D, Kim JH, Lee SH, Ho W-K. Low mobility of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate underlies receptor specificity of Gq-mediated ion channel regulation in atrial myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15241–15246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408851102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Shin J, Shin CY, Lee SY, Oh U. Mechanosensitive ion channels in cultured sensory neurons of neonatal rats. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1238–1247. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01238.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edidin M. The state of lipid rafts: from model membranes to cells. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2003;32:257–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.142439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo EM, Cante-Barrett K, Crabtree GR. Lymphocyte calcium signaling from membrane to nucleus. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:25–32. doi: 10.1038/ni1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N, DeFranco AL. Visualizing lipid raft dynamics and early signaling events during antigen receptor-mediated B-lymphocyte activation. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:432–444. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-05-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Martinac B. Molecular basis of mechanotransduction in living cells. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:685–740. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempel WM, DeFranco AL. Expression of phospholipase C isozymes by murine B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1991;146:3713–3720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW, Feng S, Nasuhoglu C. The complex and intriguing lives of PIP2 with ion channels and transporters. Sci STKE. 2001;2001:RE19. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.111.re19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LF, Hirdes W, Suh BC, Hilgemann DW, Mackie K, Hille B. Phospholipase C in living cells: activation, inhibition, Ca2+ requirement, and regulation of M current. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:243–262. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CL, Feng S, Hilgemann DW. Direct activation of inward rectifier potassium channels by PIP2 and its stabilization by Gβγ. Nature. 1998;391:803–806. doi: 10.1038/35882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilsdonk EP, Yancey PG, Stoudt GW, Bangerter FW, Johnson WJ, Phillips MC, Rothblat GH. Cellular cholesterol efflux mediated by cyclodextrins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17250–17256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Sekiya F, Poulin B, Bae YS, Rhee SG. Mechanism of B-cell receptor-induced phosphorylation and activation of phospholipase C-γ2. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9986–9999. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.9986-9999.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu QH, Liu X, Wen Z, Hondowicz B, King L, Monroe J, Freedman BD. Distinct calcium channels regulate responses of primary B lymphocytes to B cell receptor engagement and mechanical stimuli. J Immunol. 2005;174:68–79. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S, Wang J, Gambhir A, Murray D. PIP2 and proteins: interactions, organization, and information flow. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:151–175. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.082901.134259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miah SM, Sada K, Tuazon PT, Ling J, Maeno K, Kyo S, Qu X, Tohyama Y, Traugh JA, Yamamura H. Activation of Syk protein tyrosine kinase in response to osmotic stress requires interaction with p21-activated protein kinase Pak2/gamma-PAK. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:71–83. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.71-83.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiaen L, De Smedt H, Parys JB, Sienaert I, Vanlingen S, Droogmans G, Nilius B, Casteels R. Hypotonically induced calcium release from intracellular calcium stores. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4601–4604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.4601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AL, Roe MW, Melnick RF, Lidofsky SD. Calcium mobilization evoked by hepatocellular swelling is linked to activation of phospholipase Cγ. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34030–34035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205945200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam JH, Woo JE, Uhm DY, Kim SJ. Membrane-delimited regulation of novel background K+ channels by MgATP in murine immature B cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20643–20654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onfelt B, Nedvetzki S, Yanagi K, Davis DM. Cutting edge: Membrane nanotubes connect immune cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:1511–1513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S, Minami Y, Hibi M, Kurosaki T, Yamamura H. Syk-dependent and -independent signaling cascades in B cells elicited by osmotic and oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2098–2103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers W, Farris D, Mishra S. Merging complexes: properties of membrane raft assembly during lymphocyte signaling. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruwhof C, van Wamel JT, Noordzij LA, Aydin S, Harper JC, van der Laarse A. Mechanical stress stimulates phospholipase C activity and intracellular calcium ion levels in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Cell Calcium. 2001;29:73–83. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth SS, Sciorra VA, Sigal YJ, Pamuklar Z, Wang Z, Xu Y, Prestwich GD, Morris AJ. Lipid phosphate phosphatases regulate lysophosphatidic acid production and signaling in platelets: studies using chemical inhibitors of lipid phosphate phosphatase activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43214–43223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh BC, Hille B. Regulation of ion channels by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HL, Janmey PA. Phosphoinositide regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:761–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Jefferson AB, Auethavekiat V, Majerus PW. The protein deficient in Lowe syndrome is a phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 5-phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4853–4856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu P, Liu X, Labelle EF, Freedman BD. Mechanisms of hypotonicity-induced calcium signaling and integrin activation by arachidonic acid-derived inflammatory mediators in B cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:4981–4989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.4981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Online supplemental material for this paper can be accessed at:

http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2007.128413/DC1 and

http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/suppl/10.1113/jphysiol.2007.128413