Abstract

Antidromic cortical excitation has been implicated as a contributing mechanism for high-frequency deep brain stimulation (DBS). Here, we examined the reliability of antidromic responses of type 2 corticofugal fibres in rat over a stimulation frequency range compatible to the DBS used in humans. We activated antidromically individual layer V neurones by stimulating their two subcortical axonal branches. We found that antidromic cortical excitation is not as reliable as generally assumed. Whereas the fast conducting branches of a type 2 axon in the highly myelinated brainstem region follow high-frequency stimulation, the slower conducting fibres in the poorly myelinated thalamic region function as low-pass filters. These fibres fail to transmit consecutive antidromic spikes at the beginning of high-frequency stimulation, but are able to maintain a steady low-frequency (6–12 Hz) spike output during the stimulation. In addition, antidromic responses evoked from both branches are rarely present in cortical neurones with a more hyperpolarized membrane potential. Our data indicate that axon-mediated antidromic excitation in the cortex is strongly influenced by the myelo-architecture of the stimulation site and the excitability of individual cortical neurones.

Therapeutic deep brain stimulation (DBS) in the thalamus and basal ganglia, provides lasting symptomatic relief in a number of neurological conditions (Lozano et al. 2002; Benabid et al. 2005; Vidailhet et al. 2005). The original rationale for DBS was that stimulation inhibited the neurones at or near the stimulation electrode thus mimicking the effects of a lesion, although it is now recognized that effects on neuronal firing pattern may be more important (Dostrovsky & Lozano, 2002). Furthermore, it is increasingly becoming clear that axons may be an important and perhaps overlooked element in understanding the mechanism of DBS (McIntyre & Thakor, 2002; Vitek, 2002).

The biophysical and geometric properties of axons render them significantly more excitable than other neural elements (McIntyre & Grill, 1999). Persistent stimulation applied to an axon can evoke repetitive axonal discharges, transmittable to multiple brain regions both chemically, through synaptic transmission, and electrically via antidromic excitation. Regarding the former, recent studies show that simulated DBS, when applied at high frequency, often depresses glutamatergic synaptic transmission resulting in a functional deafferentation and/or de-rhythmicity (Kiss et al. 2002; Anderson et al. 2004, 2006; Iremonger et al. 2006). The role of antidromic excitation, however, remains unclear. Some clinical and experimental observations have implicated cortical antidromic excitation as an important contributing factor in thalamic DBS (Ashby & Rothwell, 2000; Hanajima et al. 2004; Usui et al. 2005) whereas others have not. For example, functional imaging studies reveal haemodynamic signals in response to DBS that appear in brain regions distant from, but connected to, the stimulation site. However, the response pattern and the direction of the evoked responses are not always compatible with the existence of an antidromic mechanism (Ceballos-Baumann et al. 2001; Lozano et al. 2002; Perlmutter et al. 2002; Perlmutter & Mink, 2006). Similarly, at a cellular level, despite the fact that stimulation of the internal or external capsule can evoke antidromic spikes in cortical cells and their dendrites (Koester & Sakmann, 1998; Gulledge & Stuart, 2003; Klueva et al. 2003), the occurrence of such antidromic responses and spike backpropagation can be highly unreliable if stimulation is applied at high frequency and/or within the grey matter or terminal fields consisting of thin branching fibres (Swadlow, 1998; Kelly et al. 2001; Rose & Metherate, 2001; Anderson et al. 2006; Iremonger et al. 2006). Therefore, a better understanding of the functional and anatomical constraints imposed by the underlying axonal networks may help establish the physiological basis of antidromic excitation and its heterogeneity.

The mechanism of axonal spike initiation, conduction and failure has been extensively investigated in invertebrates but less so in the mammalian CNS, mainly because of its small size (Hille, 2001). For several reasons, we were particularly interested in cortical descending axons from the layer V output cells. First, layer V axons provide innervations to many brain regions, including the basal gangalia, thalamus and brainstem, where DBS has been applied (Green et al. 2006; Perlmutter & Mink, 2006; Velasco et al. 2006). Second, the subcortical or type 2 axons of layer V cells have been well characterized. For example, type 2 axons in monkey ventrolateral nucleus of the thalamus (which is a preferred DBS target for tremors (Ilinsky & Kultas-Ilinsky, 2002)) are characterized by a thick trunk that gives off many thin collaterals with large terminal boutons (Kultas-Ilinsky et al. 2003). This typical structure of type 2 axons is also present in many other thalamic nuclei (Levesque et al. 1996; Pare & Smith, 1996; Deschenes et al. 1998; Jones, 2001) and especially prominent in the posterior thalamus (PT) (Rockland, 1996,1998; Guillery & Sherman, 2002; Rouiller & Durif, 2004). Finally, the branching pattern and terminal fields of type 2 axons are considered similar to those of the ascending sensory fibres from the retina or cerebellum, both of which provide driver input to the thalamus (Guillery & Sherman, 2002). Hence, studying layer V axons may reveal important insights into the general physiological basis of antidromic cortical excitation in both motor and sensory corticofugal systems.

Previous in vivo electrophysiological studies of corticothalamic fibres have largely focused on the characterization of axonal conduction speed, laminar profile and waveform distinctions (Swadlow, 1998; Kelly et al. 2001). Little information is available regarding fibre response to sustained high-frequency stimulation and how axonal response can be affected by the stimulation sites or variations in fibre surroundings. Ideally, such a study should be conducted without the interference of anaesthetics or synaptic influences (Swadlow, 1998). It should also allow unambiguous placements of electrical stimulation at different regions along the fibre path because the properties of axons may change as they transverse from grey to white matter or vice versa (Salami et al. 2003). A previous attempt to obtain a slice preparation from rat thalamus that is suitable for studying corticothalamic fibres in the motor system was largely unsuccessful (Iremonger et al. 2006). On the other hand, it has been shown that slices through the PT cut horizontally contain large bundles of descending layer V axons (Cruikshank et al. 2002). In a pilot study using a modified version of this preparation, we have confirmed that the axons in this preparation belong to type 2 axons (Chomiak & Hu, 2004, 2005). They are characterized by the corticotectal branch and a collateral in the PT (Rockland, 1998). Stimulation of the corticotectal branch in the heavily myelinated pretectal area can evoke a fast antidromic cortical excitation in layer V neurones. In the same cell, a slower antidromic response can be elicited from its thalamic collateral in the poorly myelinated region of the PT (Chomiak & Hu, 2004, 2005). In the present study, we referred to these two pathways as PT and brainstem (BrS) fibres, respectively. We now report that high-frequency stimulation of cortical type 2 fibres can produce distinct patterns of antidromic cortical excitation.

Methods

Preparation

All experimental protocols were approved by the University of Calgary Animal Care Committee. Briefly, Sprague-Dawley and Long-Evans rats (150–200 g) were anaesthetized with halothane and decapitated and the brain was removed. The tissue was quickly submerged in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) and then placed on a cold Plexiglass stage. Horizontal sections (425 μm thick) were cut on a vibrotome at ∼25–30 deg relative to the dorsal surface, as reported previously (Cruikshank et al. 2002). Horizontal slices were incubated in aCSF for 1–2 h before recording. Slices were superfused with oxygenated (95% 02–5% CO2) aCSF at 4–6 ml min−1. The aCSF had a final pH of 7.6, an osmolality of 300 ± 3 mosmol kg−1 and contained (mm): NaCl 122, KCl 3, MgCl2 1.3, NaHCO3 25.9, CaCl2 2.5 and glucose 11. The patch electrode solution contained (mm): potassium gluconate 140, KCl 10, Na-Hepes 10, Na-GTP 0.2 and Mg-ATP 4. The pipette solution was adjusted to a final osmolality of 283 ± 3 mosmol kg−1 with potassium gluconate and buffered to pH 7.2 with 1 m KOH. All electrophysiological experiments were performed at 30–32°C. The DC resistance of the patch electrodes was 6–8 MΩ. Signal acquisition and analysis was accomplished with the Clampex 9 data acquisition system (Axon Instruments, CA, USA).

Electrophysiology

Recordings were restricted to layer V of the associational cortex Temporal lobe area 2 (Te2) and caudal Temporal lobe area 3 (Te3) regions (Vaudano et al. 1991). Microstimulation (typically ≤ 100 μA, 50–200 μs) was made through bipolar stimulating electrodes with a separation distance of 500 μm. Both mono- and biphasic stimulation pulses delivered through bipolar electrodes were effective in evoking antidromic action potentials (APs) (Miocinovic & Grill, 2004). Stimulus pulses were controlled by a DS8000 digital stimulus pattern generator (WPI, FL, USA). We limited our stimulus rate to between 0.5 and 100 Hz because this frequency range is clinically beneficial (Ushe et al. 2004, 2006). We also obtained the charge threshold (Qthes) (in coulombs) for axonal spike initiation according to: Qthres=[i(Q/s)·t(s)]thres where t is the stimulus pulse duration and i is the current strength (Davies, 1968; Ranck, 1975). Antidromic latencies were determined by measuring the time interval between the initial stimulation artefact and the onset of the antidromic AP. As spike initiation follows the terminating edge of the stimulus pulse (Davies, 1968; McIntyre & Grill, 1999), the pulse duration was subtracted from the measurements. This method, together with using antidromic spike onset rather than its peak latency, reduces the uncertainties associated with the different stimulus pulse durations needed for different axons (Ranck, 1975). Data are expressed as means ±s.d. The latency values are expressed as geometric mean ± 95% confidence interval because they failed the D'Agostino and Pearson normality test. Statistical comparisons (P values) were derived from ANOVA and post hoc comparisons, except for the charge threshold and latency comparisons for which parametric and non-parametric t tests were used, respectively.

Histology

Slices used for electrophysiological studies were fixed in paraformaldehyde and 4% sucrose overnight at 4°C. Tissue blocks from PT and BrS stimulation sites were removed, immersed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde fixative/0.1 m sodium cacodylate buffer. They were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide/0.1 m sodium cacodylate buffer, thoroughly rinsed and dehydrated with 70% acetone. Tissues were embedded in 1: 1 acetone:resin for 1 h followed by 100% resin for 1 h and then 100% resin overnight. Tissues were then placed in 100% resin for 1 h before placing into moulds with fresh resin, followed by polymerization in a 60°C oven overnight. Thin sections (0.3 μm) were collected on microscopy slides, coverslipped and viewed with brightfield optics. Images were captured through a high-resolution CCD camera. Ultra-thin sections (0.07 μm) were collected on copper mesh grids for transmission electron microscopy. Multiple visual fields of each stimulation site from three different sections (with the dimensions of ∼1 mm × 2 mm) were analysed. Myelinated axonal densities were obtained from a total area of 3700 μm2.

Results

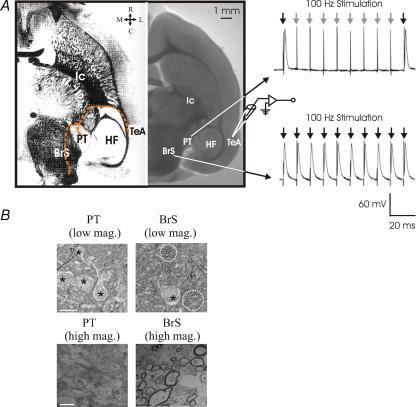

Figure 1 illustrates the slice preparation, and the stimulation and recording sites. Bipolar stimulation electrodes were placed in the PT and BrS in the same slice in a rostral–caudal orientation. Both these structures can be readily identified under differential interference contrast microscopy based on their locations relative to the hippocampus and ventricle wall, and the intensities of light reflection (Fig. 1A). Once a whole-cell recording was obtained, stimulus trains were delivered at different frequencies to the PT or BrS (Fig. 1A, right panel). For the purpose of illustrating the difference in the degree of fibre myelination between the two regions, a previously published photograph of Loyez fibre staining is attached (Kruger et al. 1995) (Fig. 1A, left panel). We have further investigated the myelo-architecture of the PT and BrS using light and electron microscopy. As shown in Fig. 1B, tissue sections obtained from PT neuropile revealed few plexuses of myelinated axons, with an average myelinated axonal density of 0.9 ± 1.1 per 100 μm2. By contrast, in the BrS region there is an abundance of myelinated axons, with an average density of 5.0 ± 2.8 per 100 μm2 (P < 0.001) which appear in multiple plexuses often within a single visual field (Fig. 1B, bottom panels). This axonal distribution pattern is consistent with that obtained using the Golgi staining method (Winer & Morest, 1984) and that observed at the macroscopic level (Kruger et al. 1995).

Figure 1. Myelo-architecture of the PT and BrS.

A, left-hand image is a myelin-stained horizontal section from published atlas by Kruger et al. 1995). The right image is our slice preparation. PT and BrS regions can be readily identified under differential interference contrast microscopy. The orange dashed line indicates the approximate axonal pathways from the temporal lobe (Cruikshank et al. 2002). The right-hand panel illustrates the cortical responses to 100 Hz stimulation in the PT and BrS. Arrowheads indicate stimulation artefact and onset. Black arrowheads indicate successful antidromic APs whereas grey arrowheads indicate failures. PT electrode was placed to the lateral edge of the PT (marked as PT). The BrS electrode was placed medial to the PT (BrS). B, axonal organization of PT and BrS fibres. Top, low magnification view of neuropiles from PT and BrS. Asterisks indicate cell bodies, and dotted circles indicate myelinated neuropile and axonal plexuses. Note the cell density is lower for the BrS site. Bottom, electron microscopy images illustrating numerous myelinated axons in BrS site. Scale bar for A is 10 μm and for B is 1 μm. Ic, internal capsule; HF, hippocampal formation; Te2, temporal lobe recording site; PT, posterior thalamus stimulation site; BrS, brain stem stimulation site.

Responses to different frequencies of antidromic stimulation in PT and BrS fibres

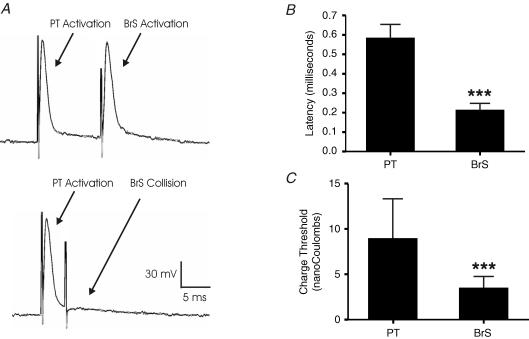

We used conventional criteria including fixed spike latency (jitter, < 0.1 ms; n= 35) and lack of synaptic potentials to identify antidromic spikes, and reciprocal collision test to identify PT and BrS fibres from the same neurone (Fig. 2A). As reported before (Lipski, 1981; Swadlow, 1998), the response following sustained high-frequency stimulation is not a reliable indicator for antidromic response.

Figure 2. Antidromic responses evoked from PT and BrS.

A, a representative example of reciprocal cancellation. Antidromic responses with fixed latencies are evoked by consecutive PT and BrS stimuli. Note that there are no synaptic potentials following the spikes. Shortening the delay between the two stimuli (< 5 ms) causes a failure of BrS stimulus (or vice versa), indicating that both APs arise from collaterals that share the same segment of an axon. B, latencies of antidromic responses. C, charge threshold data for both PT and BrS collaterals. ***P < 0.01.

As shown in Fig. 2A, antidromic excitation from PT and BrS fibres exhibited different features. First, BrS stimulation typically gave rise to reliable antidromic spikes during a 100 Hz stimulus train. By contrast, with stimulation at the PT site a large proportion of antidromic responses failed to occur, often at the beginning of the stimulation. Second, we compared the latencies of spike conduction along each pathway (Fig. 2B). The mean conduction latency along the PT collateral pathway is significantly longer (0.58 ± 0.08 ms; n= 27) than along the BrS collaterals (0.21 ± 0.03 ms; n= 25; P < 0.01). Based on the axonal path–length trajectories of these neurones as reported by Cruikshank et al. (2002), the estimated conduction velocity of each pathway is ∼10 m s−1 for PT and ∼33 m s−1 for BrS.

Finally, as expected, the charge threshold for PT collaterals (8.89 ± 4.96 nC, n= 13) is significantly higher than BrS fibres (3.41 ± 1.49 nC, n= 14, P < 0.01; Fig. 2C). These biophysical characteristics are consistent with the myelo-architectural differences between the two fibre pathways (Fig. 1B).

Axonal filtering of high-frequency stimulation

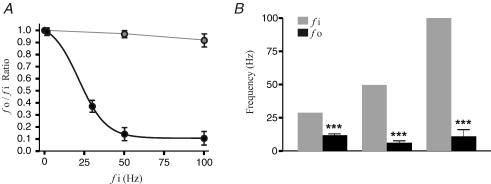

The high proportion of antidromic AP failures from stimulation at the PT site (Fig. 1A) suggests that PT axons do not lead to faithful antidromic cortical excitation as commonly assumed. To further examine this issue, we applied different frequencies of extracellular stimulation to PT axons (Fig. 3). In these tests, the membrane potential (Vm) of cortical neurones was held at more depolarized levels to ensure somatic invasion of antidromic spikes (see below). We found that axonal activation was highly reliable at 1 Hz stimulation, whereas at 30 and 50 Hz there was a significant (P < 0.01) and frequent failure of antidromic APs (Fig. 3A). We also examined whether such failures were related to the length of stimulation or the number of stimulus events. To this end, we recorded AP failure rates during 30, 50 and 100 Hz stimulation (n= 10) while varying the number of stimulus events (i.e. 50, 100, 150 and 200). We found no statistical difference between length of stimulation and AP failure rate (P > 0.05; data not shown). The ratio of axonal output (fo) and input frequency (fi) Next we plotted the ratio of the antidromic activation (fo) to stimulation input (fi) by calculating the number of antidromic APs divided by the number of stimuli to see how axonal output from each pathway was correlated to stimulation frequency (Fig. 3A). A ratio of 1 represents complete stimulus–response coupling, whereas a ratio of 0.1 indicates that there is one AP for every 10 stimuli. We found a fo/fi ratio close to 1 at low stimulation frequencies that decreased rapidly with increasing stimulation frequency. Figure 3A shows are the mean fo/fi (and range) obtained for a given frequency, which drops from about 1.0 for 1 Hz stimulation to 0.1 at 100 Hz stimulation (n= 21). By contrast, fibres activated from the BrS region maintained a fo/fi ratio near 1 for all stimulation frequencies (Fig. 3A). Hence, for PT fibres the average number of antidromic APs decreases with increasing stimulation frequency. This feature is characteristic of an inverse sigmoidal (R2= 1.0) low-pass filter response (Serway et al. 2000), with an average cut-off frequency (fo/fi= 0.5) of 10.8 Hz. Finally, we compared fo obtained for each fi during multiple trials. We found that although the average corresponding fo frequency is significantly reduced (P < 0.01), the inter-trial comparisons revealed no statistical difference in fo (P > 0.05). In other words, once the low-pass cut-off frequency has been reached (∼10.8 Hz; Fig. 3A and B), axonal output is independent of the stimulation frequency, further indicating that the low-pass filtering property is independent of trial numbers, stimulus event sequence and fi.

Figure 3. Low-pass filtering of PT axonal output.

A, the ratio of axonal output (fo) and input frequency (fi) is plotted as a function of fi. A ratio of 1 represents complete coupling between axonal output and extracellular stimulation. B, the average fo for each fi (30, 50 and 100 Hz). Note that 30, 50 and 100 Hz are all above the low-pass cut-off frequency of ∼10 Hz. There is no statistical difference between all output frequencies above the cut-off. For BrS stimulation, there is no statistical difference between different output frequencies. The data for PT are shown in black, and for BrS are shown in grey for A and B. ***P < 0.01.

Somatic gating of antidromic excitation

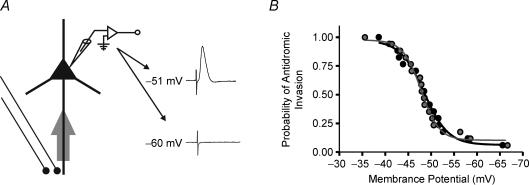

APs initiated from axons can backpropagate into pyramidal cell dendrites and modify synaptic excitability and plasticity (Koester & Sakmann, 1998; Gulledge & Stuart, 2003). Although such backward cortical excitation may have important implications for DBS, its probability of occurrence is uncertain. Therefore, we examined whether the reliability of antidromic spike propagation evoked in PT versus BrS fibres is affected by varying the Vm of the cell (Fig. 4A) (Coombs et al. 1955; Lipski, 1981). We calculated the probabilities of PT and BrS antidromic somatic invasion as a function of Vm and found a sigmoidal dependence of antidromic somatic invasion on Vm (Fig. 4B; R2= 0.985 for both). In all 17 neurones tested, reliable antidromic invasion from each site only took place between −45 and −50 mV (Fig. 4B). This probability of neurons activated (Nactivated) versus total (Ntotal) neurons was reduced to about 20% if neurones were held at a voltage between −63 and −67 mV, suggesting that at normal resting Vm (around −60 mV), the majority of the antidromic spikes can be filtered out at the cell body. This somatic gating was a general phenomenon, found for both the BrS and PT fibre collaterals (Fig. 4B), and was independent of stimulation frequency (n= 15).

Figure 4. Somatic gating of antidromic APs.

A, schematic diagram of recording and stimulation configuration. Two raw traces obtained from the same neurone are shown. One was obtained at the resting membrane potential (Vm; −60 mV, bottom), below the threshold for somatic antidromic invasion, and the other above the threshold Vm (−51 mV, top). B, summary of probabilities of antidromic somatic invasion (Nactivated/Ntotal) as a function of Vm. Data from PT (black) and BrS (grey) are from the same neurones. The data follow a sigmoidal relationship (R2= 0.985) for each stimulation site indicating common axonal trunk sharing of antidromically invading APs. Stimulation was at 0.5 Hz.

Discussion

Axonal response to high-frequency extracellular electrical stimulation has not been systematically examined in the corticofugal system. The main objective of our study was to investigate the physiological and anatomical constraints that may facilitate or limit the occurrence of antidromic responses during simulated DBS in the corticofugal system. Because cortical layer V cells located in motor and sensory cortices share many similarities in terms of their membrane properties, fibre myelination and pattern of axonal branching (Deschenes et al. 1998; Steriade, 2004), the findings reported here are also applicable to other cortical projections.

Experimental design

The first issue that needs to be considered here is the relevance of our experimental design to clinical DBS. Our choice of studying 1–100 Hz stimulation is based on the reports that thalamic DBS in this frequency range elicits a steep inverse-sigmoidal frequency-dependent reduction in hand or shoulder tremors; little additional benefit occurs above 100 Hz (Ushe et al. 2004, 2006). With regard to the stimulation sites, Mason et al. (2000) and Ilinsky & Kultas-Ilinsky (2002) reported that the ventral motor thalamic region of primates is the equivalent target for DBS in humans, where a large number of type 2 corticothalamic axons from the motor cortex are present). These fibres are similar to the layer V axons found in the PT where type 2 axons were first described and later characterized in great detail (Rockland, 1996,1998; Deschenes et al. 1998; Guillery et al. 2001; Rouiller & Durif, 2004). Therefore, although technical hurdles have so far prevented us from directly examining type 2 axons in motor thalamus in vitro, there is no reason to believe the antidromic response of type 2 axons obtained from PT will differ from those in the motor thalamus.

Low-pass filtering of PT axons

The limited capacity of PT fibres to produce high-frequency antidromic APs is an intriguing and potentially important phenomenon. One obvious possibility is that repetitive intrathalamic stimuli and spiking caused an accumulation of extracellular K+ that subsequently blocked the AP via membrane depolarization or a change in membrane excitability (Parnas & Segev, 1979). This possibility, however, seems incompatible with our data for several reasons. First, the observed AP failure and low-pass filtered response appeared almost immediately after the first spike (Fig. 1), instead of evolving during the stimulation. This time course seems too abrupt to be ascribed to K+ build-up in slices (Somjen, 2001). Second, if a K+-mediated mechanism applies, then heavily myelinated axons should be more likely to develop a depolarization blockade because of the presence of the peri-axonal space and circulating currents (Blight, 1985; Blight & Someya, 1985; Richardson et al. 2000; Debanne, 2004). Indeed, we were able to show that myelinated axons and plexuses are conspicuous in the BrS region and these fibres exhibited high-fidelity spike conduction instead of failures.

It is known that the geometric inhomogeneities (e.g. branch points and varicosities) can result in impedance mismatch and capacitance loads between the approaching and conducting branch(es), leading to AP failures (Goldstein & Rall, 1974; Lopez-Aguado et al. 2002). However, impedance mismatch is not the only factor that can cause AP failure. Parnas & Segev (1979) suggested that membrane excitability change at the branch point in response to [K+] increase can also contribute to AP failure. In a recent modelling study of branched myelinated fibres, Zhou & Chiu (2001) showed that temperature, local K+ ion accumulation, width of the peri-axonal space and internodal lengths can all affect the AP transmission from the parent axon to the daughter branch, thus allowing for occasional branch point failures to function as a low-pass filter and signal integrator. On the other hand, experimental work in the rat neocortex has shown that branch point and impedance mismatch may not be necessarily an effective mechanism to block AP conduction (Cox et al. 2000; Huguenard, 2000). Regarding type 2 corticofugal axons, detailed information about the fine structure of branch points remains lacking. Based on published data (Rouiller et al. 1992; Rockland, 1996,1998; Deschenes et al. 1998; Guillery et al. 2001), the difference in axonal diameters between a parent axon and its collateral is likely to be 2- to 3-fold at most branch points. The length of internodal myelin sheath around these branch points is also likely to vary (Waxman, 1972; Deschenes & Landry, 1980) to accommodate en passant synapses and varicosities along the collateral branches. Hence, branch points could be the main anatomical site involved in low-pass filtering.

Another mechanism involved in low-pass axonal filtering may be related to the model of Richardson et al. (2000). Based on the original experimental and theoretical work of Blight, (1985) and Blight & Someya (1985), Richardson et al. (2000) investigated the effects of extracellular electrical stimulation on axons and the role of the myelin sheath in maintaining spike output. They found that APs can faithfully follow high-frequency stimuli in myelinated fibres because the peri-axonal space between the axolemma and the thick myelin sheath allows for a depolarizing after-potential (DAP) to occur after each AP, which in turn facilitates high-frequency output. Removal of the DAP from the model results in a prevailing after-hyperpolarizing potential (AHP), working against high-frequency axonal output, effectively resulting in a low-pass filtered response (Richardson et al. 2000). The AHP may originate from different types of K+ currents (Coetzee et al. 1999; Burke et al. 2001) and/or result from the electrogenic Na+–K+-ATPase (Rang & Ritchie, 1968; Koketsu, 1971). Both the myelo-architectural differences between the BrS and PT sites (Fig. 1B) and the long duration (∼90 ms), opposed to occasional, failure pattern of the PT branch, are more consistent with this model.

Somatic AP gating

Our data show that somatic antidromic spikes are only present in cortical cells that are more depolarized. A similar phenomenon was noticed in spinal motor neurones but was not characterized (Coombs et al. 1955; Lipski, 1981). We estimated that for cortical neurones with a membrane potential below −55 mV, antidromic somatic excitation occurs with less than 50% probability. Under in vivo conditions, therefore, the balance of excitatory and inhibitory input and the functional state of a given cortical neurone will largely decide whether antidromic excitation from subcortical stimulation will take place. Recently, several studies have demonstrated that the AP in cortical layer V pyramidal cells and cerebellar Purkinje cells first initiates at the first node of Ranvier (Stuart et al. 1997; Clark et al. 2005). However, the backward propagation of APs to the soma is controlled by the axon initial segment intervening the node and cell body where a high level of K+ channels and GABAergic innervations are present (Inda et al. 2006). The latter two features may help hyperpolarize the local Vm and serve as an inhibitory mechanism to prevent antidromic spike invasion to the soma. Artificial somatic current injection, on the other hand, can depolarize the initial segment (Shu et al. 2006) and bring its potential closer to the firing threshold.

Functional implications

In a slice model of simulated DBS, Anderson et al. (2004) showed that high-frequency thalamic stimulation can quickly result in transmitter depletion and failure of synaptic transmission in the thalamus. However, they did not obtain the evidence that the abolished synaptic response is not due to axonal conduction failure. The present study shows that conduction failure is unlikely to be a contributing factor because even for thin PT collaterals high-frequency stimulation did not result in a total loss of axonal APs. Instead, it produced low-frequency spike output which was ineffective in inducing transmitter depletion (Anderson et al. 2006) and may contribute to the sustained synaptic depolarization observed in some thalamic cells in that study.

Layer V cortical neurones possess elaborate dendritic arbors that extend throughout the cortical thickness and highly collateralized axonal projections innervating multiple cortical and subcortical targets (Deschenes et al. 1994). As a result, the axonal low-pass filtered response may have two important consequences. First, the large interspike interval (∼90 ms) of the filtered response may permit ‘normal’ communication between cortical layer V neurones and their targets because antidromic–orthodromic collisions will not occur during this 90 ms period. On the other hand, if antidromic excitation is faithful, as in heavily myelinated axons, antidromic–orthodromic collisions would prevent cortical layer V output from reaching its targets. Second, sustained low-frequency antidromic excitation is better at backpropagating throughout the dendritic arbor of layer V neurones than high-frequency antidromic excitation (Gulledge & Stuart, 2003). This may lead to greater Ca2+ influx (Koester & Sakmann, 1998) and retrograde glutamate release (Ali et al. 2001) which may lead to long-term effects on cortical network dynamics. However, this form of backpropagation will be subject to somatic gating which tends to minimize excitation coupling between the axon and dendrite.

The enhancement in haemodynamic response of blood flow is tightly coupled to energy consumption and oxygen supply incurred mostly during AP firing and excitatory synaptic activities (Attwell & Iadecola, 2002; Lennie, 2003). Because APs and their propagation consume a significantly larger mount of energy than synaptic potentials and resting membrane potential, neocortical neurones tend to rely on a sparse coding principle to process information, which requires fewer active neurones and lower (< 20 Hz) firing rate (Lennie, 2003). Under this physiological condition, the large amount of antidromic APs that are evoked by DBS, if unfiltered, could become a significant contributor to the haemodynamic response observed during human functional imaging experiments. Testing this hypothesis may prove to be difficult in reciprocally connected brain structures where an antidromic effect is confounded by orthodromic responses as well as by the excitatory and inhibitory activities generated within the local synaptic network. On the other hand, in certain conditions of DBS an axonal component of a haemodynamic response appears highly likely. One such condition is related to the neural pathways where DBS is thought to inhibit synaptic activities and neuronal firing and yet haemodynamic measurement yields opposite signals. For example, thalamic DBS often induces a strong local haemodynamic response around the stimulation site (Ceballos-Baumann et al. 2001; Perlmutter et al. 2002). This is despite the fact that local synaptic activities are expected to be depressed due to DBS-induced glutamate transmitter depletion (Anderson et al. 2006) and/or inhibition from GABAergic reticular neurones and interneurones (Sherman et al. 1997). Similarly, DBS applied to the subthalamic nucleus in patients with Parkinson's disease also increases thalamic blood flow, in spite of enhanced thalamic inhibition provided by the GABAergic pallidothalamic pathway (Perlmutter & Mink, 2006). We suspect that such ‘paradoxical’ haemodynamic responses incurred during synaptic inhibition may result from enhanced axonal spiking. In the case of local thalamic stimulation, this mechanism may be particularly robust due to the fact that APs can be elicited both anti- and orthodromically from multiple sources of axons, including the corticofugal fibres (both main branches and collaterals) from layers V and VI pyramidal cells, as well as those from the thalamocortical projection neurones and intrathalamic interneurones.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Z. Kiss and T. Anderson for their helpful comments. This study was supported by Canadian Institute of Health Research and Regenerative Medicine Team Grants to B.H.

References

- Ali AB, Rossier J, Staiger JF, Audinat E. Kainate receptors regulate unitary IPSCs elicited in pyramidal cells by fast-spiking interneurons in the neocortex. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2992–2999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-02992.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson T, Hu B, Iremonger K, Kiss ZH. Selective attenuation of afferent synaptic transmission as a mechanism of thalamic deep brain stimulation-induced tremor arrest. J Neurosci. 2006;26:841–850. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3523-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson T, Hu B, Pittman Q, Kiss ZH. Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation: an intracellular study in rat thalamus. J Physiol. 2004;559:301–313. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.064998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby P, Rothwell JC. Neurophysiologic aspects of deep brain stimulation. Neurology. 2000;55:S17–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D, Iadecola C. The neural basis of functional brain imaging signals. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:621–625. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benabid AL, Wallace B, Mitrofanis J, Xia R, Piallat B, Chabardes S, Berger F. A putative generalized model of the effects and mechanism of action of high frequency electrical stimulation of the central nervous system. Acta Neurol Belg. 2005;105:149–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blight AR. Computer simulation of action potentials and afterpotentials in mammalian myelinated axons: the case for a lower resistance myelin sheath. Neuroscience. 1985;15:13–31. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blight AR, Someya S. Depolarizing afterpotentials in myelinated axons of mammalian spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1985;15:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke D, Kiernan MC, Bostock H. Excitability of human axons. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1575–1585. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00595-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos-Baumann AO, Boecker H, Fogel W, Alesch F, Bartenstein P, Conrad B, et al. Thalamic stimulation for essential tremor activates motor and deactivates vestibular cortex. Neurology. 2001;56:1347–1354. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.10.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomiak T, Hu B. Characterization of auditory corticothalamic pathway in vitro. Abstr Soc Neurosci. 2004 Program no. 987.18. [Google Scholar]

- Chomiak T, Hu B. High-frequency extracellular electrical stimulation of a single mammalian axon leads to differential frequency. Abstr Soc Neurosci. 2005 Program no. 180.14. [Google Scholar]

- Clark BA, Monsivais P, Branco T, London M, Hausser M. The site of action potential initiation in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:137–139. doi: 10.1038/nn1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee WA, Amarillo Y, Chiu J, Chow A, Lau D, McCormack T, et al. Molecular diversity of K+ channels. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;868:233–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs JS, Eccles JC, Fatt P. The electrical properties of the motoneurone membrane. J Physiol. 1955;130:291–325. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CL, Denk W, Tank DW, Svoboda K. Action potentials reliably invade axonal arbors of rat neocortical neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9724–9728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.170278697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruikshank SJ, Rose HJ, Metherate R. Auditory thalamocortical synaptic transmission in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:361–384. doi: 10.1152/jn.00549.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PW. Classical electrophysiology. In: Mountcastle VB, editor. Medical Physiology. 12. Vol. 2. St Louis: The CV Mosby Co; 1968. pp. 1073–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D. Information processing in the axon. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:304–316. doi: 10.1038/nrn1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschenes M, Bourassa J, Pinault D. Corticothalamic projections from layer V cells in rat are collaterals of long-range corticofugal axons. Brain Res. 1994;664:215–219. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91974-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschenes M, Landry P. Axonal branch diameter and spacing of nodes in the terminal arborization of identified thalamic and cortical neurons. Brain Res. 1980;191:538–544. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschenes M, Veinante P, Zhang Z-W. The organization of corticothalamic projections: reciprocity versus parity. Brain Res Rev. 1998;28:286–308. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dostrovsky JO, Lozano AM. Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation. Mov Disord. 2002;17(Suppl. 3):S63–S68. doi: 10.1002/mds.10143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein SS, Rall W. Changes of action potential shape and velocity for changing core conductor geometry. Biophys J. 1974;14:731–757. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(74)85947-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AL, Wang S, Owen SL, Paterson DJ, Stein JF, Aziz TZ. Controlling the heart via the brain: a potential new therapy for orthostatic hypotension. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:1176–1183. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000215943.78685.01. discussion 1176–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillery RW, Feig SL, Van Lieshout DP. Connections of higher order visual relays in the thalamus: a study of corticothalamic pathways in cats. J Comp Neurol. 2001;438:66–85. doi: 10.1002/cne.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillery RW, Sherman SM. Thalamic relay functions and their role in corticocortical communication: generalizations from the visual system. Neuron. 2002;33:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulledge AT, Stuart GJ. Action potential initiation and propagation in layer 5 pyramidal neurons of the rat prefrontal cortex: absence of dopamine modulation. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11363–11372. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11363.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanajima R, Ashby P, Lozano AM, Lang AE, Chen R. Single pulse stimulation of the human subthalamic nucleus facilitates the motor cortex at short intervals. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1937–1943. doi: 10.1152/jn.00239.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Huguenard JR. Reliability of axonal propagation: the spike doesn't stop here. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9349–9350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilinsky IA, Kultas-Ilinsky K. Motor thalamic circuits in primates with emphasis on the area targeted in treatment of movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2002;17(Suppl. 3):S9–S14. doi: 10.1002/mds.10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inda MC, DeFelipe J, Munoz A. Voltage-gated ion channels in the axon initial segment of human cortical pyramidal cells and their relationship with chandelier cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2920–2925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511197103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iremonger K, Anderson TR, Hu B, Kiss ZH. Cellular mechanisms preventing sustained activation of cortex during subcortical high frequency stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:613–621. doi: 10.1152/jn.00105.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG. The thalamic matrix and thalamocortical synchrony. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:595–601. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01922-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MK, Carvell GE, Hartings JA, Simons DJ. Axonal conduction properties of antidromically identified neurons in rat barrel cortex. Somatosens Mot Res. 2001;18:202–210. doi: 10.1080/01421590120072196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss ZH, Mooney DM, Renaud L, Hu B. Neuronal response to local electrical stimulation in rat thalamus: physiological implications for mechanisms of deep brain stimulation. Neuroscience. 2002;113:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klueva J, Munsch T, Albrecht D, Pape HC. Synaptic and non-synaptic mechanisms of amygdala recruitment into temporolimbic epileptiform activities. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:2779–2791. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.02984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koester HJ, Sakmann B. Calcium dynamics in single spines during coincident pre- and postsynaptic activity depend on relative timing of back-propagating action potentials and subthreshold excitatory postsynaptic potentials. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9596–9601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koketsu K. The electrogenic sodium pump. Adv Biophys. 1971;2:77–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger L, Saporta S, Swanson LW. Photographic Atlas of the Rat Brain: the Cell and Fiber Architecture Illustrated in Three Planes with Stereotaxic Coordinates. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kultas-Ilinsky K, Sivan-Loukianova E, Ilinsky IA. Reevaluation of the primary motor cortex connections with the thalamus in primates. J Comp Neurol. 2003;457:133–158. doi: 10.1002/cne.10539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennie P. The cost of cortical computation. Curr Biol. 2003;13:493–497. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque M, Charara A, Gagnon S, Parent A, Deschenes M. Corticostriatal projections from layer V cells in rat are collaterals of long-range corticofugal axons. Brain Res. 1996;709:311–315. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipski J. Antidromic activation of neurones as an analytic tool in the study of the central nervous system. J Neurosci Methods. 1981;4:1–32. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(81)90015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Aguado L, Ibarz JM, Varona P, Herreras O. Structural inhomogeneities differentially modulate action currents and population spikes initiated in the axon or dendrites. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2809–2820. doi: 10.1152/jn.00183.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano AM, Dostrovsky J, Chen R, Ashby P. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease: disrupting the disruption. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre CC, Grill WM. Excitation of central nervous system neurons by nonuniform electric fields. Biophys J. 1999;76:878–888. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77251-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre CC, Thakor NV. Uncovering the mechanisms of deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease through functional imaging, neural recording, and neural modeling. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2002;30:249–281. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v30.i456.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason A, Ilinsky IA, Maldonado S, Kultas-Ilinsky K. Thalamic terminal fields of individual axons from the ventral part of the dentate nucleus of the cerebellum in Macaca mulatta. J Comp Neurol. 2000;421:412–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miocinovic S, Grill WM. Sensitivity of temporal excitation properties to the neuronal element activated by extracellular stimulation. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;132:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare D, Smith Y. Thalamic collaterals of corticostriatal axons: their termination field and synaptic targets in cats. J Comp Neurol. 1996;372:551–567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960902)372:4<551::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnas I, Segev I. A mathematical model for conduction of action potentials along bifurcating axons. J Physiol. 1979;295:323–343. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter JS, Mink JW. Deep brain stimulation. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:229–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter JS, Mink JW, Bastian AJ, Zackowski K, Hershey T, Miyawaki E, Koller W, Videen TO. Blood flow responses to deep brain stimulation of thalamus. Neurology. 2002;58:1388–1394. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.9.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranck JB., Jr Which elements are excited in electrical stimulation of mammalian central nervous system: a review. Brain Res. 1975;98:417–440. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rang HP, Ritchie JM. On the electrogenic sodium pump in mammalian non-myelinated nerve fibres and its activation by various external cations. J Physiol. 1968;196:183–221. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson AG, McIntyre CC, Grill WM. Modelling the effects of electric fields on nerve fibres: influence of the myelin sheath. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2000;38:438–446. doi: 10.1007/BF02345014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockland KS. Two types of corticopulvinar terminations: round (type 2) and elongate (type 1) J Comp Neurol. 1996;368:57–87. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960422)368:1<57::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockland KS. Convergence and branching patterns of round, type 2 corticopulvinar axons. J Comp Neurol. 1998;390:515–536. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980126)390:4<515::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose HJ, Metherate R. Thalamic stimulation largely elicits orthodromic, rather than antidromic, cortical activation in an auditory thalamocortical slice. Neuroscience. 2001;106:331–340. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouiller EM, Durif C. The dual pattern of corticothalamic projection of the primary auditory cortex in macaque monkey. Neurosci Lett. 2004;358:49–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouiller EM, Wan XS, Moret V, Liang F. Mapping of c-fos expression elicited by pure tones stimulation in the auditory pathways of the rat, with emphasis on the cochlear nucleus. Neurosci Lett. 1992;144:19–24. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90706-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salami M, Itami C, Tsumoto T, Kimura F. Change of conduction velocity by regional myelination yields constant latency irrespective of distance between thalamus and cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6174–6179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937380100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serway R, Beichner RJ, Jewett JW. Physics for Scientists and Engineers. Philadelphia: Saunders College Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SE, Luo L, Dostrovsky JO. Altered receptive fields and sensory modalities of rat VPL thalamic neurons during spinal strychnine-induced allodynia. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:2296–2308. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.5.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Y, Hasenstaub A, Duque A, Yu Y, McCormick DA. Modulation of intracortical synaptic potentials by presynaptic somatic membrane potential. Nature. 2006;441:761–765. doi: 10.1038/nature04720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somjen GG. Mechanisms of spreading depression and hypoxic spreading depression-like depolarization. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1065–1096. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M. Neocortical cell classes are flexible entities. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:121–134. doi: 10.1038/nrn1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Schiller J, Sakmann B. Action potential initiation and propagation in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 1997;505:617–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.617ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swadlow HA. Neocortical efferent neurons with very slowly conducting axons: strategies for reliable antidromic identification. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;79:131–141. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)00176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushe M, Mink JW, Revilla FJ, Wernle A, Schneider Gibson P, McGee-Minnich L, Hong M, Rich KM, Lyons KE, Pahwa R, Perlmutter JS. Effect of stimulation frequency on tremor suppression in essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1163–1168. doi: 10.1002/mds.20231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushe M, Mink JW, Tabbal SD, Hong M, Schneider Gibson P, Rich KM, Lyons KE, Pahwa R, Perlmutter JS. Postural tremor suppression is dependent on thalamic stimulation frequency. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1290–1292. doi: 10.1002/mds.20926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui N, Maesawa S, Kajita Y, Endo O, Takebayashi S, Yoshida J. Suppression of secondary generalization of limbic seizures by stimulation of subthalamic nucleus in rats. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:1122–1129. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.6.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaudano E, Legg CR, Glickstein M. Afferent and efferent connections of temporal association cortex in the rat: a horseradish peroxidase study. Eur J Neurosci. 1991;3:317–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1991.tb00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco AL, Velasco F, Jimenez F, Velasco M, Castro G, Carrillo-Ruiz JD, Fanghanel G, Boleaga B. Neuromodulation of the centromedian thalamic nuclei in the treatment of generalized seizures and the improvement of the quality of life in patients with Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1203–1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidailhet M, Vercueil L, Houeto JL, Krystkowiak P, Benabid AL, Cornu P, et al. Bilateral deep-brain stimulation of the globus pallidus in primary generalized dystonia. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:459–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitek JL. Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation: excitation or inhibition. Mov Disord. 2002;17(Suppl. 3):S69–S72. doi: 10.1002/mds.10144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman SG. Regional differentiation of the axon: a review with special reference to the concept of the multiplex neuron. Brain Res. 1972;47:269–288. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90639-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA, Morest DK. Axons of the dorsal division of the medial geniculate body of the cat: a study with the rapid Golgi method. J Comp Neurol. 1984;224:344–370. doi: 10.1002/cne.902240304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Chiu SY. Computer model for action potential propagation through branch point in myelinated nerves. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:197–210. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]