Abstract

Donors of nitroxyl (HNO), the reduced congener of nitric oxide (NO), exert positive cardiac inotropy/lusitropy in vivo and in vitro, due in part to their enhancement of Ca2+ cycling into and out of the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Here we tested whether the cardiac action of HNO further involves changes in myofilament–calcium interaction. Intact rat trabeculae from the right ventricle were mounted between a force transducer and a motor arm, superfused with Krebs–Henseleit (K-H) solution (pH 7.4, room temperature) and loaded iontophoretically with fura-2 to determine [Ca2+]i. Sarcomere length was set at 2.2–2.3 μm. HNO donated by Angeli's salt (AS; Na2N2O3) dose-dependently increased both twitch force and [Ca2+]i transients (from 50 to 1000 μm). Force increased more than [Ca2+]i transients, especially at higher doses (332 ± 33% versus 221 ± 27%, P < 0.01 at 1000 μm). AS/HNO (250 μm) increased developed force without changing Ca2+ transients at any given [Ca2+]o (0.5–2.0 mm). During steady-state activation, AS/HNO (250 μm) increased maximal Ca2+-activated force (Fmax, 106.8 ± 4.3 versus 86.7 ± 4.2 mN mm−2, n = 7–8, P < 0.01) without affecting Ca2+ required for 50% activation (Ca50, 0.44 ± 0.04 versus 0.52 ± 0.04 μm, not significant) or the Hill coefficient (4.75 ± 0.67 versus 5.02 ± 1.1, not significant). AS/HNO did not alter myofibrillar Mg-ATPase activity, supporting an effect on the myofilaments themselves. The thiol reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT, 5.0 mm) both prevented and reversed HNO action, confirming AS/HNO redox sensitivity. Lastly, NO (from DEA/NO) did not mimic AS/HNO cardiac effects. Thus, in addition to reported changes in Ca2+ cycling, HNO also acts as a cardiac Ca2+ sensitizer, augmenting maximal force without altering actomyosin ATPase activity. This is likely to be due to modulation of myofilament proteins that harbour reactive thiolate groups that are targets of HNO.

While the effects of nitric oxide (NO) on cardiac function have been widely reported, the influence of its one-electron-reduced form, termed nitroxyl (HNO), has only recently been appreciated (Wink et al. 2003; Paolocci et al. 2006). HNO donors exert a positive, load-independent inotropic action in both normal (Paolocci et al. 2001) and failing hearts (Paolocci et al. 2003). HNO cardiotropy is additive to β-agonist effects and not prevented by β-blockade (Paolocci et al. 2003). HNO's in vivo cardiovascular action is distinct from that produced by NO donors or nitrate, in that those have only modest (Preckel et al. 1997) or negligible inotropic effects on resting myocardium (Weyrich et al. 1994), but depress β-stimulated inotropy (Balligand, 1999; Brunner et al. 2001; Brunner & Wolkart, 2003; Sears et al. 2004). Also, unlike that of NO, the action of HNO is significantly blunted or even abolished if the intracellular content of reducing equivalents is increased, supporting the role of targeted thiolate groups in HNO chemistry (Fukuto et al. 2005; Paolocci et al. 2006).

The physiological effects of HNO donors suggest potential use as a novel treatment for cardiac failure, raising the importance of better understanding its cellular and molecular mechanism. HNO potentially stimulates Ca2+ release from ryanodine receptors (RyRs) in cardiac (Tocchetti et al. 2007) and skeletal muscles (Cheong et al. 2005), but also increases sarcoplasmic reticular Ca2+ uptake so that net diastolic calcium remains low. These effects appear to be independent of both cGMP- and cAMP-coupled signalling (Tocchetti et al. 2007).

In addition to changes in Ca2+ handling, HNO may alter contractility by modifying the myofilament protein response to calcium. NO donors (Brunner et al. 2001; Layland et al. 2002) and NO related species such as peroxynitrite (Brunner & Wolkart, 2003) reduce myofilament Ca2+ responsiveness in a cGMP-dependent manner. It is unknown whether HNO has similar or potentially opposite effects that might contribute to its enhancement of force. To test this, we investigated the effect of the HNO donor, Angeli's salt (AS; Na2N2O3), on cardiac force–Ca2+ dependence and excitation–contraction coupling in intact rat ventricular trabeculae. The results show dose-dependent increases in both [Ca2+]i transients and force as well as enhanced myofilament responsiveness to Ca2+.

Methods

Animals

Rats (Sprague–Dawley, 250–300 g, n = 31) were used in these experiments. The care of the animals and the experiment protocol were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Trabecular muscle preparation

The rats were anaesthetized (pentobarbital 100 mg kg−1) via intra-abdominal injection, and the heart was exposed by mid-sternotomy, rapidly excised and placed in a dissection dish. The aorta was cannulated and the heart perfused retrogradely (∼15 mm min−1) with dissecting Krebs–Henseleit (H-K) solution equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The dissecting K-H solution was composed of (mm): NaCl 120, NaHCO3 20, KCl 5, MgCl 1.2, glucose 10, CaCl2 0.5, and 2,3-butanedione monoximine (BDM) 20, pH 7.35–7.45 at room temperature (21–22°C). Trabeculae from the right ventricle of the heart were dissected and mounted between a force transducer and a motor arm. Then, they were superfused with normal K-H solution (KCl, 5 mm) at a rate of ∼10 ml min−1 and stimulated at 0.5 Hz. Dimensions of the muscles (n = 40) were measured with a calibration reticule in the ocular of the dissection microscope (× 40, resolution ∼10 μm):

Force and sarcomere length measurements

Force was measured using a force transducer system (KG7, Scientific Instruments GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) and was expressed in millinewtons per square millimetre of cross-sectional area. Sarcomere length was measured by laser diffraction (Gao et al. 1996a). Briefly, light diffracted by the central region of the muscle was detected by a reticon diode linear array system (RC0100-RG512, EG & G Reticon, Calgary, Canada). The light intensity of the first order of diffraction was integrated, and sarcomere length determined from the median of the light intensity distribution using a custom-made sarcomere length detection system (University of Calgary, Canada). Resting sarcomere length was set at 2.20–2.30 μm throughout the experiments.

Measurement of [Ca2+]i

[Ca2+]i was measured using the free acid form of fura-2 as described in previous studies (Gao et al. 1994, 1998; Backx et al. 1995). Fura-2 potassium salt was microinjected iontophoretically into one cell and allowed to spread throughout the whole muscle (via gap junctions). The tip of the electrode (∼0.2 μm in diameter) was filled with fura-2 salt (1 mm) and the remainder of the electrode was filled with 150 mm KCl. After a successful impalement into a superficial cell in non-stimulated muscle, a hyperpolarizing current of 5–10 nA was passed continuously for ∼15 min. In some muscles, multiple injections (up to 3–4) were applied at different sites, with duration of the injection limited to < 10 min at each site to achieve a good signal-to-noise ratio. As previously established, this loading did not affect force development. Fura-2 epifluorescence was measured by exciting at 380 and 340 nm. Fluorescent light was collected at 510 nm by a photomultiplier tube (R1527, Hamamatsu, Shizuka, Japan). The output of the photomultiplier was collected and digitized. [Ca2+]i was given by the following equation (after subtraction of the autofluorescence):

| (1) |

where R is the observed ratio of fluorescence (340/380), K′d is the apparent dissociation constant, Rmax is the ratio of 340 nm/380 nm at saturating [Ca2+], and Rmin is the ratio of 340 nm/380 nm at zero [Ca2+]. The values of K′d, Rmax and Rmin were determined by in vivo calibrations as previously described (Gao et al. 1994, 1998).

Steady-state activation of trabeculae

Ryanodine (1.0 μm) was used to enable steady-state activation. After 15 min of exposure to ryanodine, different levels of tetanizations were induced briefly (∼4–8 s) by stimulating the muscles at 10 Hz at varied [Ca2+]o (0.5–20 mm). All experiments were performed at room temperature (20–22°C).

Myofibrillar Mg-ATPase activity measurement

Myofibrils were prepared from cardiac ventricle as previously described (Murphy & Solaro, 1990) with careful use of protease inhibitors. Assays were performed using incubation conditions established by varying the total concentration of metals, salts and ligands and maintaining ionic strength using stability constants compiled by Fabiato (1981). Assays were performed at pH 7.0 with 50 mm imidazole, 50 mm KCl and 2 mm MgATP. Inorganic phosphate liberation was measured using a microtitre plate version of the standard assay as described by Rarick et al. (1997). Protein concentration was determined by a variation of the Lowry method (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). In the final assay conditions, myofibrillar protein concentration was diluted in buffer to have a concentration of 0.2 mg ml−1 in the assay, and protein concentration determined once again for final calculations. Mg-ATPase activity was calculated in nanomoles of inorganic phosphate liberated per milligram of myofibrillar protein per minute.

Statistics

Student's t test and one-way ANOVA were used for statistical analysis of the data (Systat, version 10.2.01; Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). A value of P < 0.05 was considered to indicate significant differences between groups. Unless otherwise indicated, pooled data are expressed as means ± s.e.m.

Results

HNO increases force development more than [Ca2+]i transients in intact rat trabeculae

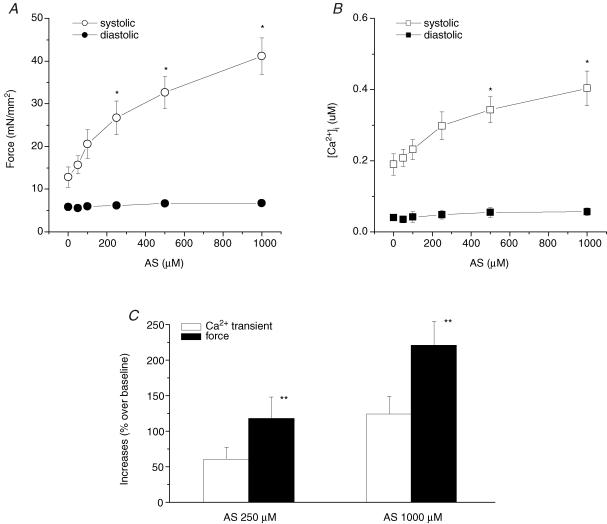

We first determined whether Angeli's salt (AS), a HNO donor, increases [Ca2+]i transients and force development in isolated rat cardiac muscles in a dose-dependent manner. Figure 1 shows representative traces of force development and corresponding [Ca2+]i transients when exposed to AS. The increase in force was not due to changes in alkalization of the K-H buffer since buffer pH was unaltered at all AS/HNO concentrations used (data not shown). Figure 2 shows that systolic force increased as a function of AS concentration without changes in diastolic force. Concomitantly, systolic [Ca2+]i increased without changes in diastolic [Ca2+]i. While both rose, increased systolic force was more pronounced than the rise in systolic [Ca2+]i, supporting an effect on myofilament force augmentation.

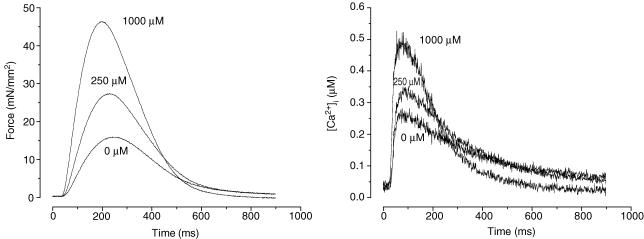

Figure 1. Respresentative tracings of force (left) and [Ca2+]i transients (right) at different doses of Angeli's salt (AS).

Both force development and [Ca2+]i transient increased at higher AS concentrations. Experimental temperature was 22°C. Sarcomere length was set at 2.2–2.3 μm and [Ca2+]o = 1.0 mm.

Figure 2. Pooled data of force development and [Ca2+]i transients at varied concentrations of AS.

Both force (A) and [Ca2+]i transients (B) increased in a dose dependent manner after exposing to AS. The increases in developed force were more than the increases in [Ca2+]i transients (C). AS did not affect neither diastolic force nor diastolic [Ca2+]i levels. Temperature, 22°C; sarcomere length, 2.2–2.3 μm; [Ca2+]o = 1.0 mm; n = 8–9 in each group. *P < 0.01 versus baseline; **P < 0.05 versus increases in [Ca2+]i transients.

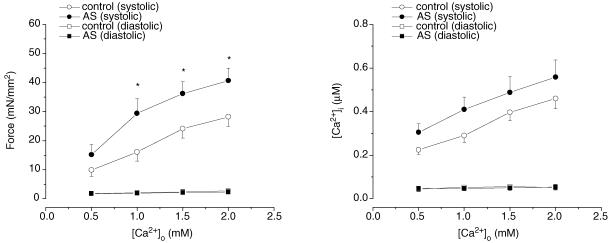

When external Ca2+ was raised, both control and AS-treated muscles ([AS] = 250 μm) developed higher force (Fig. 3). However, force remained significantly higher in AS-treated than control muscles at any given external Ca2+ concentration (P < 0.001). On the other hand, the amplitude of intracellular Ca2+ transients increased ∼50% and was not different between control and AS-treated muscles (P > 0.05). Figure 4 provides summary data for twitch and Ca2+ transient kinetics. The times to peak for force and Ca2+ transient were shortened by 250 μm AS/HNO (P < 0.05). Relaxation rates for both behaviours were also faster (P < 0.05).

Figure 3. Pooled data of force development and [Ca2+]i transients at varied [Ca2+]o in the absence (open symbols) and presence (filled symbols) of AS (250 μm).

Force increased significantly at any given [Ca2+]o in the presence of AS (P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA, n = 7 in each group). There was no difference in increase in [Ca2+]i transients between the two groups (P > 0.05). *P < 0.05 versus corresponding controls.

Figure 4. Dynamics of twitch forces and corresponding [Ca2+]i transients from AS-treated (•) and control (^) muscles at varied [Ca2+]o values.

Multivariate ANOVA showed significant differences in both time to peak and time to half-relaxation between the two groups. n = 5 in each group; P < 0.05.

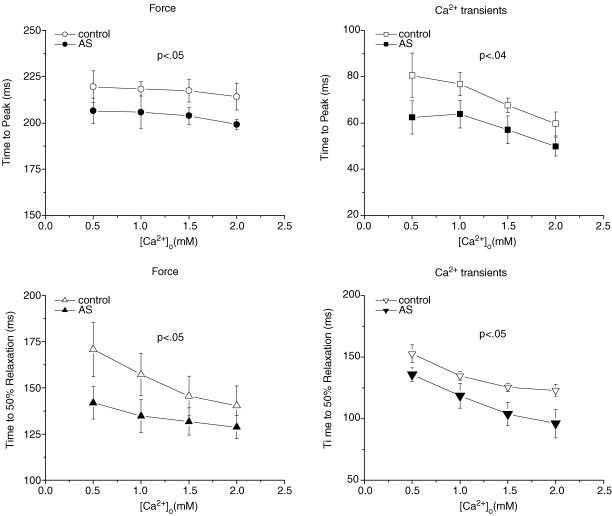

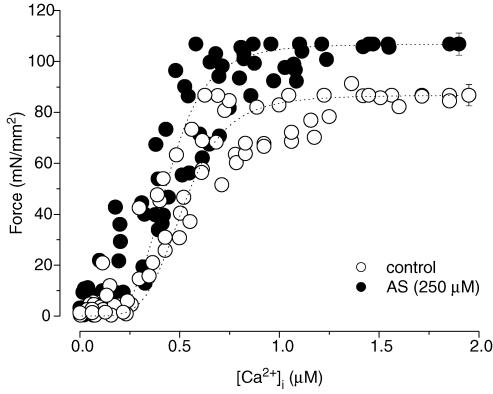

HNO increases muscle responsiveness to Ca2+ in intact rat trabeculae

The preceding analysis was based on transient force and Ca2+ analysis, not with both parameters at equilibrium. To better assess myofilament properties, we tetanized muscles to achieve steady-state myofilament activation over a broad range of [Ca2+]i, and then tested the effect of AS/HNO. Pooled results of this steady-state force–[Ca2+]i analysis are shown in Fig. 5 for controls (n = 7) and preparations exposed to AS (250 μm, n = 8). Data were normalized to their respective maximal values, and plotted against the means of the absolute maximal value for each group. In untreated muscles, maximal Ca2+-activated force was 86.7 ± 4.2 mN mm−2, and the [Ca2+]i required for 50% of activation was 0.52 ± 0.04 μm. Peak force increased in muscles exposed to AS (106.8 ± 4.3 mN mm−2 P < 0.01 versus control), while the [Ca2+]i required for 50% activation was not significantly changed (0.44 ± 0.04 μm; P > 0.05 versus control). The Hill coefficient was not affected in AS-treated muscles (4.75 ± 0.67 versus 5.02 ± 1.10, control muscles, P > 0.05). Hence, the action of AS/HNO was to enhance maximal Ca2+-activated force.

Figure 5. Steady-state force–[Ca2+]i relations in control (^) and AS-treated (•) trabecular muscles.

Varied steady-state activations were achieved by stimulating the muscles at > 10 Hz in the presence of 1 μm ryanodine at varied [Ca2+]o values. n = 7–8 in each group.

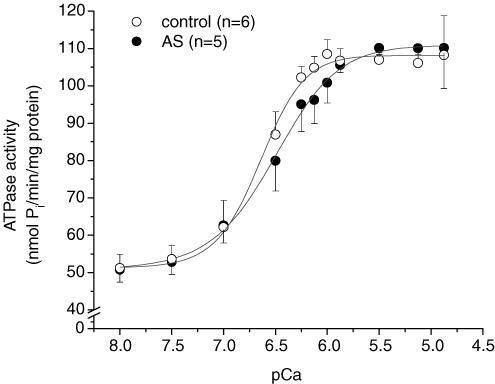

HNO does not affect myofibrillar Mg-ATPase activity

To test whether the positive inotropic action of HNO mainly involved thick/thin filament or regulatory proteins, and to assess the economy of increased Fmax by HNO, we determined Mg-ATPase activity in isolated myofibrils from controls and hearts treated with AS/HNO. The maximal Ca2+-activated Mg-ATPase activity was 110.1 ± 10.8 nmol Pi min−1 (mg protein)−1 in AS-treated hearts (P > 0.1 versus control 108.2 ± 10.5 nmol Pi min−1 (mg protein)−1) (Fig. 6). Thus, AS/HNO increased force development without increasing ATP consumption, supporting improved economy and action most likely targeted to regulatory proteins.

Figure 6. Myofibrillar Mg-ATPase sensitivity to Ca2+.

Isolated rats were either treated with AS (250 μm) for 20 min (•, n = 5) or continuously perfused for 35–40 min (^, n = 6). The Ca2+ for half-maximally activated Mg-ATPase activity (pCa50) was not affected by AS (6.55 ± 0.14 versus 6.70 ± 0.08, control, P = 0.4). See text for details.

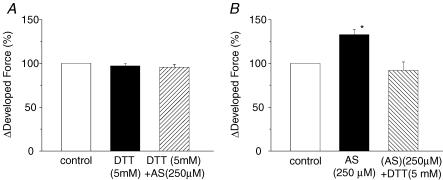

HNO-induced force development is sensitive to intracellular reducing equivalents

Given its thiophilic nature (Fukuto et al. 2005), HNO action is expected to be highly sensitive to redox state and thus amount of intracellular reducing equivalents (Miranda et al. 2003; Wink et al. 2003; Fukuto et al. 2005). We therefore tested whether manipulating intracellular thiol content with DTT (5 mm) before and after treating the muscles with AS influenced the sensitizing effect. DTT had no effect on basal force development; however, it blocked AS (250 μm, n = 4)-induced force augmentation (Fig. 7A). In additional experiments, muscles were first exposed to AS (250 μm) to increase force, and then shortly after stopping AS (force was still elevated), DTT was administered. This avoided direct mixing of AS and DTT in the bath. DTT reversed AS force increase within ∼5–10 min (Fig. 7B). In the absence of DTT, force would remain elevated for over 20 min. Thus, DTT both prevented and reversed the effect of AS on force development.

Figure 7. Effect of DTT on force development in the presence and absence of AS.

DTT (5 mm) not only prevented (A, n = 4) but also reversed (B, n = 3) the effect of AS on force development. [Ca2+]o = 1.0 mm; *P < 0.05 versus control.

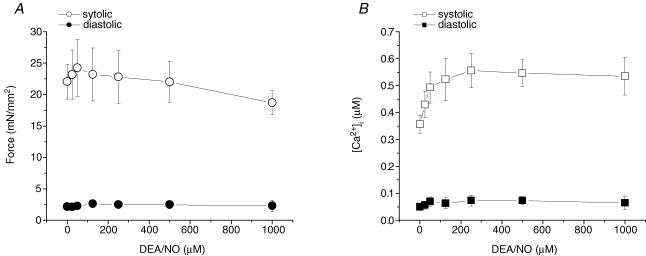

Nitric oxide (from DEA/NO) does not reproduce HNO's effect on force in intact rat trabeculae

HNO and NO have very different effects on in vivo cardiac contractility (Miranda et al. 2003; Wink et al. 2003), but whether similar divergent effects occur at the intact muscle level is unknown. We therefore exposed trabeculae to the NO donor DEA/NO which has an identical half-life to AS (HNO) in physiological buffer at room temperature. DEA/NO only slightly increased twitch force and [Ca2+]i transients up to a dose of 125 μm. At higher contractions (1.0 mm), force decreased slightly with no change in the [Ca2+]i transient. Both diastolic force and [Ca2+]i transient were unaltered (Fig. 8). DEA/NO (125 μm) did not affect the steady-state force–[Ca2+]i relationship (data not shown).

Figure 8. Pooled data of force (A) and [Ca2+]i transients (B) at different concentrations of diethylamine/NO (DEA/NO), a NO donor.

Low doses of DEA/NO (up to 120 μm) increased force and [Ca2+]i transients. In contrast to AS, force decreased at higher concentrations of DEA/NO while [Ca2+]i transients remained unchanged. Temperature, 22°C; sarcomere length, 2.2–2.3 μm; n = 4.

Discussion

This is the first study to show that HNO donated by Angeli's salt exerts a direct dose–response positive inotropic action in isolated, intact cardiac muscle. This involves an increase in both developed force and the peak [Ca2+]i transient, but these changes are disproportionate, underlined by an increase in sensitivity due to a rise in maximal Ca2+- activated force. Fmax increase is energetically favourable because Mg-ATPase activity doesn't change with AS/HNO. In addition, HNO response is very different from that of NO, and is blocked by the reducing agent DTT, supporting strong redox sensitivity.

NO and HNO differ by only a single electron. Yet, HNO is predicted to undergo addition reactions with thiols and ferric proteins (Miranda et al. 2003) whereas NO does not readily do so. NO preferentially targets non-O2-binding cytosolic ferrous soluble guanylyl cyclase (Murad, 1994), whereas thiol proteins or peptides are the major targets for the biological action of HNO (Fukuto et al. 2005). Although cGMP-independent contractile effects of NO have been also described (Chesnais et al. 1999; Sarkar et al. 2000; Paolocci et al. 2000), the majority of NO cardiac actions are linked to cGMP/PKG activation (Layland et al. 2005; Massion et al. 2005). A substantial body of evidence supports the notion that cGMP/PKG activation is a major transduction pathway for NO cardiac regulation (and its oxidized congeners), whereby they depress contractility by myofilament desensitization to Ca2+. Such desensitization is thought to be responsible for accelerated myocardial relaxation. This can be prevented by PKG pharmacological blockade or genetic deletion (Layland et al. 2005), and has been attributed to cTnI phosphorylation at Ser23/24 (Layland et al. 2005). The reactive nitrogen species peroxynitrite also reduces myofilament Ca2+ responsiveness, leading to cardiodepressant effects that are partly mediated by PKG (Brunner & Wolkart, 2003).

HNO responses are very different. This may be due to its inability to interact with guanylyl cyclase and/or primary targeting of critical cysteine residues in the contractile machinery (Paolocci et al. 2006). This chemistry is not likely to be a generalized oxidation process for several reasons. First, muscles exposed to oxygen free radical generating systems (H2O2 + Fe3+ and xanthine oxidase + purine) display reduced force and Ca2+ transients (Gao et al. 1996b). Xanthine oxidase + purine reduces myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity associated with a fall in Fmax and increased Ca50 (Gao et al. 1996b). These changes are likely to reflect the oxidation of several key myofibrillar proteins (Canton et al. 2004). HNO has been postulated to react with select thiolates (−S), highly reactive subpopulations of thiols (−SH) (Fukuto et al. 2005), which would confer both selectivity and reversibility of action. The latter is supported by the present and prior data showing that inotropic (and sensitization) effects are readily reversible with DTT. Studies in isolated SR vesicles from rabbit hearts (Cheong et al. 2005) or murine myocytes (Tocchetti et al. 2007) have found HNO-induced SR Ca2+ release is also fully reversed by DTT. HNO selectivity has also been revealed in a recent study performed in yeast in which it was found to specifically target glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in its active site thiolate residue without altering overall thiol content of the cells (Lopez et al. 2005).

On these grounds, we hypothesize that HNO induces similar selective chemical modifications on cysteine ‘hot-spots’ within the myofilaments. Whether these modifications occur in thick or thin myofilaments is not yet known, though the finding that myofilament actomyosin Mg-ATPase activity was not affected by HNO suggests myosin is an unlikely primary target. However, the finding that HNO increased only maximal Ca2+-activated force strongly supports the view that cross-bridge cycling is involved. Indeed, force development depends not only upon the number of attached cross-bridges but also upon their kinetic behaviour. Cross-bridge turnover rate can profoundly affect force–pCa relations (Brenner, 1993), with increases in the rate of attachment and/or decreases in the rate of detachment enhancing Ca2+-activated force (Brenner, 1984, 1993; Campbell, 1997). Cross-bridge cycling changes by HNO may represent a unique way to augment contraction, and it is likely that this occurs through thiol modifications within the regulatory proteins. Several inotropic agents increase force via binding to (or interacting with) troponins that are key regulators of muscle contraction and force generation. For instance, EMD-57033 increases force by binding to troponin C, resulting in increased myofibrillar ATPase activity (Soergel et al. 2004). Tropomyosin, troponin C, troponin I, and myosin light chain I and II all have potential cysteine(s) for HNO that could in turn underlie the change in sensitivity. Future studies are needed to identify which of these targets is indeed important.

Consistent with data in isolated myocytes, the current study shows that HNO increases the [Ca2+]i transient along with force in intact cardiac muscle. In cardiac myocytes, HNO enhances both Ca2+ uptake and release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, modestly raising the transient without adversely altering diastolic Ca2+ (Tocchetti et al. 2007), and this could explain the observed changes in Ca2+ transient in the current study. These mechanisms would be in addition to the enhancement of force due to greater Ca2+ sensitivity, suggesting a novel and orchestrated action of HNO with the cardiac myofilaments and SR to enhance inotropy and lusitropy at potentially lower energetic cost.

It is worth contrasting the behaviour of HNO to those of other well-studied calcium sensitizers. EMD-57033, which binds to TnC (Pan & Johnson, 1996), is thought to directly modify myosin/actin crossbridge force in the tightly bound configuration, increasing both the sensitivity and peak tension in skinned muscle fibres (Gross et al. 1993). Unlike HNO (cf. Fig. 4), EMD-57033 prolongs systole and does not enhance relaxation rate (Slinker et al. 1997; Senzaki et al. 2000). Levosimendan also targets cTnC (Haikala et al. 1995), but in addition, inhibits phosphodiesterase 3 and activates ATP-sensitive potassium channels (Yokoshiki & Sperelakis, 2003; Szilagyi et al. 2005). It shifts the force–Ca2+ relation leftward at systolic Ca2+ but not at lower Ca2+ concentrations (Levijoki et al. 2000). This latter behaviour appears true of HNO as well, and can be an advantage since sensitization at lower Ca2+ poses the potential risk of adversely effecting diastolic function. Allopurinol, a xanthine oxidase inhibitor, increases maximal Ca2+-activated force in isolated cardiac muscles (Perez et al. 1998). Its mechanism of action for force augmentation is at present unclear but may depend on the balance between oxidative stress and nitric oxide synthase activity (Saavedra et al. 2002). The similarity between HNO and allopurinol in their actions on maximal Ca2+-activated force is intriguing given some chemical properties of HNO. For example, a recent study found that HNO can inhibit xanthine oxidase in a feedback fashion (Saleem & Ohshima, 2004).

One limitation of the study is that AS is not a pure HNO donor, but coreleases both HNO and nitrite (Miranda et al. 2005). Our in vivo (Paolocci et al. 2003) and in vitro studies (Tocchetti et al. 2007) have already shown that nitrite does not stimulate an inotropic response, and in vivo elicits primarily vasodilatation (Paolocci et al. 2003). Still, development of pure HNO donors will help to better dissect the biochemistry and mechanism.

In conclusion, HNO provided by AS augments force development more than intracellular Ca2+ transient in rat cardiac muscle, in part due to an increase in myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. This effect is sensitive to a reducing environment. Further study is needed to identify the primary myofibril molecular target(s) underlying this effect.

Acknowledgments

Angeli's salt (AS, Na2N2O3) was a generous gift of Dr Jon M. Fukuto and Matthew I. Jackson (UCLA). This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (HL44065 to Dr Gao, HL075265 to Dr Paolocci, HL077180 to Dr Kass and HL63038 to Dr Murphy), and the American Heart Association (SDG to Dr Paolocci).

References

- Backx PH, Gao WD, Azan-Backx MD, Marban E. The relationship between contractile force and intracellular [Ca2+] in intact rat cardiac trabeculae. J General Physiol. 1995;105:1–19. doi: 10.1085/jgp.105.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balligand JL. Regulation of cardiac β-adrenergic response by nitric oxide. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;43:607–620. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B. The cross-bridge cycle in muscle. Mechanical, biochemical, and structural studies on single skinned rabbit fibers to characterize cross-bridge kinetics in muscle for correlation with the actomyosin-ATPase in solution. Basic Res Cardiol. 1984;81:1–15. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-11374-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B. Changes in calcium sensitivity at the cross-bridge level. In: Lee JA, Allen DG, editors. Modulation of Cardiac Calcium Sensitivity: A New Approach to Increasing the Strength of the Heart. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 197–214. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner F, Andrew P, Wolkart G, Zechner R, Mayer B. Myocardial contractile function and heart rate in mice with myocyte-specific overexpression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2001;104:3097–3102. doi: 10.1161/hc5001.101966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner F, Wolkart G. Peroxynitrite-induced cardiac depression: role of myofilament desensitization and cGMP pathway. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell K. Rate constant of muscle force redevelopment reflects cooperative activation as well as cross-bridge kinetics. Biophys J. 1997;72:254–262. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78664-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canton M, Neverova I, Menabo R, Van Eyk J, Di Lisa F. Evidence of myofibrillar protein oxidation induced by postischemic reperfusion in isolated rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H870–H877. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00714.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong E, Tumbev V, Abramson J, Salama G, Stoyanovsky DA. Nitroxyl triggers Ca2+ release from skeletal and cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum by oxidizing ryanodine receptors. Cell Calcium. 2005;37:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesnais J-M, Fischmeister R, Méry P-F. Positive and negative inotropic effects of NO donors in atrial and ventricular fibres of the frog heart. J Physiol. 1999;518:449–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0449p.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A. Myoplasmic free calcium concentration reached during the twitch of an intact isolated cardiac cell and during calcium-induced release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of a skinned cardiac cell from the adult rat or rabbit ventricle. J General Physiol. 1981;78:457–497. doi: 10.1085/jgp.78.5.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuto JM, Bartberger MD, Dutton AS, Paolocci N, Wink DA, Houk KN. The physiological chemistry and biological activity of nitroxyl (HNO). The neglected, misunderstood, and enigmatic nitrogen oxide. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:790–801. doi: 10.1021/tx0496800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao WD, Backx PH, Azan-Backx M, Marban E. Myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in intact versus skinned rat ventricular muscle. Circ Res. 1994;74:408–415. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao WD, Liu Y, Mellgren R, Marban E. Intrinsic myofilament alterations underlying the decreased contractility of stunned myocardium. A consequence of Ca2+-dependent proteolysis? Circ Res. 1996a;78:455–465. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao WG, Liu Y, Marban E. Selective effects of oxygen free radicals on excitation-contraction coupling in ventricular muscle. Implications for the mechanism of stunned myocardium. Circulation. 1996b;94:2597–2604. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.10.2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao WG, Perez NG, Marban E. Calcium cycling and contractile activation in intact mouse cardiac muscle. J Physiol. 1998;507:175–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.175bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross T, Lues I, Daut J. A new cardiotonic drug reduces the energy cost of active tension in cardiac muscle. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1993;25:239–244. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1993.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haikala H, Kaivola J, Nissinen E, Wall P, Levijoki J, Linden IB. Cardiac troponin C as a target protein for a novel calcium sensitizing drug, levosimendan. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:1859–1866. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(95)90009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layland J, Li JM, Shah AM. Role of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase in the contractile response to exogenous nitric oxide in rat cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 2002;540:457–467. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.014126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layland J, Solaro RJ, Shah AM. Regulation of cardiac contractile function by troponin I phosphorylation. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levijoki J, Pollesello P, Kaivola J, Tilgmann C, Sorsa T, Annila A, Kilpelainen I, Haikala H. Further evidence for the cardiac troponin C mediated calcium sensitization by levosimendan: structure-response and binding analysis with analogs of levosimendan. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:479–491. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez BE, Rodriguez CE, Pribadi M, Cook NM, Shinyashiki M, Fukuto JM. Inhibition of yeast glycolysis by nitroxyl (HNO): mechanism of HNO toxicity and implications to HNO biology. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;442:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massion PB, Pelat M, Belge C, Balligand JL. Regulation of the mammalian heart function by nitric oxide. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2005;142:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2005.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda KM, Dutton AS, Ridnour LA, Foreman CA, Ford E, Paolocci N, Katori T, Tocchetti CG, Mancardi D, Thomas DD, Espey MG, Houk KN, Fukuto JM, Wink DA. Mechanism of aerobic decomposition of Angeli's salt (sodium trioxodinitrate) at physiological pH. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:722–731. doi: 10.1021/ja045480z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda KM, Paolocci N, Katori T, Thomas DD, Ford E, Bartberger MD, Espey MG, Kass DA, Feelisch M, Fukuto JM, Wink DA. A biochemical rationale for the discrete behavior of nitroxyl and nitric oxide in the cardiovascular system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9196–9201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1430507100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murad F. Regulation of cytosolic guanylyl cyclase by nitric oxide: the NO-cyclic GMP signal transduction system. Adv Pharmacol. 1994;26:19–33. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy AM, Solaro RJ. Developmental difference in the stimulation of cardiac myofibrillar Mg2+-ATPase activity by calmidazolium. Pediatr Res. 1990;28:46–49. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199007000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan BS, Johnson RG., Jr Interaction of cardiotonic thiadiazinone derivatives with cardiac troponin C. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:817–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolocci N, Ekelund UEG, Isoda T, Ozaki M, Vandegaer K, Georgakopoulos D, Harrison R, Kass DA, Hare MJ. Cyclic nucleotide independent positive inotropic effects of nitric oxide donors: potential role for nitrosylation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H1982–H1988. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolocci N, Jackson MI, Lopez BE, Miranda K, Tocchetti CG, Wink DA, Hobbs AJ, Fukuto JM. The pharmacology of nitroxyl (HNO) and its therapeutic potential: Not just the Janus face of NO. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;113:442–458. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolocci N, Katori T, Champion HC, St John ME, Miranda KM, Fukuto JM, Wink DA, Kass DA. Positive inotropic and lusitropic effects of HNO/NO− in failing hearts: independence from beta-adrenergic signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5537–5542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937302100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolocci N, Saavedra WF, Miranda KM, Martignani C, Isoda T, Hare JM, Espey MG, Fukuto JM, Feelisch M, Wink DA, Kass DA. Nitroxyl anion exerts redox-sensitive positive cardiac inotropy in vivo by calcitonin gene-related peptide signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10463–10468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181191198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez NG, Gao WD, Marban E. Novel myofilament Ca2+-sensitizing property of xanthine oxidase inhibitors. Circ Res. 1998;83:423–430. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preckel B, Kojda G, Schlack W, Ebel D, Kottenberg K, Noack E, Thamer V. Inotropic effects of glyceryl trinitrate and spontaneous NO donors in the dog heart. Circulation. 1997;96:2675–2682. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.8.2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rarick HM, Tu XH, Solaro RJ, Martin AF. The C terminus of cardiac troponin I is essential for full inhibitory activity and Ca2+ sensitivity of rat myofibrils. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26887–26892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.26887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra WF, Paolocci N, Zeichner J, Mudrick D, Marban E, Kass DA, Hare JM. Imbalance between xanthine oxidase and nitric oxide synthase signaling pathways underling mechanoenergetic uncoupling in the failing heart. Circ Res. 2002;90:297–304. doi: 10.1161/hh0302.104531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem M, Ohshima H. Xanthine oxidase converts nitric oxide to nitroxyl that inactivates the enzyme. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;315:455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar D, Vallance P, Amirmansour C, Harding SE. Positive inotropic effects of NO donors in isolated guinea-pig and human cardiomyocytes independent of NO species and cyclic nucleotides. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;48:430–439. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears CE, Ashley EA, Casadei B. Nitric oxide control of cardiac function: is neuronal nitric oxide synthase a key component? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:1021–1044. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senzaki H, Isoda T, Paolocci N, Ekelund U, Hare JM, Kass DA. Improved mechanoenergetics and cardiac rest and reserve function of in vivo failing heart by calcium sensitizer EMD-57033. Circulation. 2000;101:1040–1048. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.9.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slinker BK, Green HW, 3rd, Wu Y, Kirkpatrick RD, Campbell KB. Relaxation effect of CGP-48506, EMD-57033, and dobutamine in ejecting and isovolumically beating rabbit hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1997;273:H2708–H2720. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.6.H2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soergal DG, Georgakopoulos D, Stull LB, Kass DA, Murphy AM. Augmented systolic response to the calcium sensitizer EMD-57033 in a transgenic model with troponim I truncation. Am J Physiol. 2004;286:H1785–H1792. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00170.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilagyi S, Pollesello P, Levijoki J, Haikala H, Bak I, Tosaki A, Borbely A, Edes I, Papp Z. Two inotropes with different mechanisms of action: contractile, PDE-inhibitory and direct myofibrillar effects of levosimendan and enoximone. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2005;46:369–376. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000175454.69116.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tocchetti CG, Wang W, Froehlich JP, Huke S, Aon MA, Wilson GM, Di Benedetto G, O'Rourke B, Gao WD, Wink DA, Toscano JP, Zaccolo M, Bers DM, Valdivia HH, Cheng H, Kass DA, Paolocci N. Nitroxyl improves cellular heart function by directly enhancing cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ cycling. Circ Res. 2007;100:96–104. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000253904.53601.c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyrich AS, Ma XL, Buerke M, Murohara T, Armstead VE, Lefer AM, Nicolas JM, Thomas AP, Lefer DJ, Vinten-Johansen J. Physiological concentrations of nitric oxide do not elicit an acute negative inotropic effect in unstimulated cardiac muscle. Circ Res. 1994;75:692–700. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wink DA, Miranda KM, Katori T, Mancardi D, Thomas DD, Ridnour L, Espey MG, Feelisch M, Colton CA, Fukuto JM, Pagliaro P, Kass DA, Paolocci N. Orthogonal properties of the redox siblings nitroxyl and nitric oxide in the cardiovascular system: a novel redox paradigm. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H2264–H2276. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00531.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoshiki H, Sperelakis N. Vasodilating mechanisms of levosimendan. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2003;17:111–113. doi: 10.1023/a:1025379400395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]