Abstract

Back-propagating action potentials (bAPs) are involved in associative synaptic plasticity and the modulation of dendritic excitability. We have used high-speed confocal and two-photon imaging to measure calcium and voltage signals associated with action potential propagation into oblique branches of CA1 pyramidal neurons in adult hippocampal slices. The spatial profile of the bAP-associated Ca2+ influx was biphasic, with an initial increase in the proximity of the branch point followed by a progressive decrease. Voltage imaging in the branches showed that bAP amplitude was initially constant and then steadily declined with distance from the soma. To determine the role of transient K+ channels in this profile, we used external Ba2+ (150 μm) as a channel blocker, after characterizing its effect on A-type K+ channels in the apical trunk. Bath application of Ba2+ significantly reduced the A-type K+ current in outside-out patches and nearly eliminated the distance-dependent decrease in bAP amplitude and its associated Ca2+ signal. Finally, small amplitude bAPs at more distal oblique branch locations could be boosted by simultaneous branch depolarization, such that the paired Ca2+ signal became nearly the same for proximal and distal oblique dendrites. These data suggest that dendritic K+ channels regulate the amplitude of bAPs to create a dendritic Ca2+ signal whose magnitude is inversely related to the electrotonic distance from the soma when bAPs are not associated with a significant amount of localized synaptic input. This distance-dependent Ca2+ signal from bAPs, however, can be amplified and a strong associative signal is produced once the proper correlation between synaptic activation and AP output is achieved. We hypothesize that these two signals may be involved in the regulation of the expression and activity of dendritic voltage- and ligand-gated ion channels.

The densities and properties of several dendritic voltage- and ligand-gated ion channels are known to markedly vary depending upon their physical location within a given neuron (Hoffman et al. 1997; Colbert et al. 1997; Jung et al. 1997; Alvarez et al. 1997; Magee, 1998; Gasparini & Magee, 2002; Smith et al. 2003; Nicholson et al. 2006). While many studies have demonstrated the profound impact that the modulation of these channels can have on single neuron information processing and storage (Hoffman et al. 1997; Magee, 1999; Magee, 2000; Hu et al. 2002), little is known about the cellular-level mechanisms that produce and maintain these channel densities and properties. Furthermore, alterations of these same channels have repeatedly been shown to underlie various forms of short- and long-term synaptic and dendritic plasticity (Heynen et al. 2000; Andrasfalvy & Magee, 2004; Frick et al. 2004; Fan et al. 2005; Magee & Johnston, 2005).

Back-propagating action potentials (bAPs) have been hypothesized to provide both distance-dependent and associative signals that could be involved in the above modulations (Spruston et al. 1995; Colbert & Johnston, 1996). Thus, it is important to determine the details of action potential back-propagation throughout the different regions of dendritic arbors. Direct electrophysiological recordings from the main apical dendrite have shown that the amplitude of the bAP decreases with distance from the soma (Stuart & Sakmann, 1994; Spruston et al. 1995; Stuart et al. 1997; Magee & Johnston, 1997). In CA1 pyramidal neurons, this decrease is largely attributable to a higher density of A-type K+ channels at distal locations within the apical trunk (Hoffman et al. 1997). While a number of studies have explored propagation within the apical trunk, less is known about propagation within the approximately 25 radial oblique dendrite branches (Frick et al. 2003; Losonczy & Magee, 2006). These branches constitute the majority of the apical dendritic area in CA1 neurons (Bannister & Larkman, 1995a) and are estimated to receive ∼80% of apical Schaffer collateral synapses (Bannister & Larkman, 1995b; Megias et al. 2001).

We have used high-speed confocal and two-photon imaging to measure calcium (Oregon Green BAPTA-1, OGB-1) and voltage (JPW 3028, Antic & Zecevic, 1995; Antic et al. 1999) signals associated with bAPs in the oblique branches of CA1 pyramidal neurons in adult slices. We have found that the amplitude of the optical signals associated with the bAPs decreases along the radial oblique branches at a rate that depends on the distance of the branch from the soma. This decrease was countered by the perfusion of Ba2+ (150 μm) or by boosting from local branch depolarization, suggesting that it could be due to a higher density of transient K+ channels in the radial oblique branches. This evidence suggests that bAPs are well suited to provide both distance-dependent and associative signals to the radial oblique dendrites and the synapses located on them.

Methods

Transverse hippocampal slices (400 μm thick) were prepared from 6- to 12-week-old-male Sprague–Dawley rats, Kv4.2 knock-out mice or their littermates, according to methods approved by the LSUHSC, MBL and University of Texas Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. Briefly, rats and mice were anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine (90 and 10 mg kg−1, respectively; additional doses were administered if the toe-pinch reflex persisted), perfused through the ascending aorta with an oxygenated solution just before death and decapitated. The external solution used for recordings contained (mm): NaCl 125, KCl 2.5, NaHCO3 25, NaH2PO4 1.25, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1 and dextrose 25 and was saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 34–36°C (pH 7.4).

Dendrites from CA1 pyramidal cells were visualized using a Zeiss Axioskop fit with differential interference contrast (DIC) optics under infrared illumination. For dendritic (whole-cell and outside-out) recordings, the internal solution contained (mm): potassium methylsulphate 140, Hepes 10, EGTA 0.5, NaCl 4, MgCl2 0.5, Mg2ATP 4, Tris2GTP 0.3, phosphocreatine 14, spermine 0.075 (pH 7.25). Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from apical dendrites (240–270 μm from the soma) were performed using a Dagan BVC-700 amplifier in the active ‘bridge’ mode. Antidromic action potentials were elicited by constant current pulses delivered through a tungsten bipolar electrode placed in the alveus. For these experiments 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-nitro-2,3-dioxo-benzo[f]quinoxaline-7-sulfonamide (NBQX; 1 μm), d(–)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (d-APV; 20 μm) and bicuculline (20 μm) were added to the external solution to block ligand-gated channels. The amplitude of the bAPs was calculated from baseline.

Dendritic outside-out patch recordings were performed at room temperature using an Axopatch 200B amplifier; TTX (0.5 μm) was added to the external solution to block Na+ currents.

For confocal imaging experiments, CA1 pyramidal somata were visualized using a Nikon E600FN (Melville, NY, USA) or an Olympus BX51 (Melville, NY, USA) microscope with infrared illumination and DIC optics, coupled with a swept field confocal system (Prairie Technologies, Middleton WI, USA). A NeuroCCD camera (RedShirt Imaging, Decatur, GA, USA) with an 80 × 80 pixel array was used to acquire the optical signal in response to excitation at 488 (for calcium imaging), 514 or 532 nm (for voltage imaging). Patch pipettes had a resistance of 2–4 mΩ when filled with a solution containing (mm): potassium methylsulphate 120, KCl 20, Hepes 10, NaCl 4, Mg2ATP 4, Tris2GTP 0.3, phosphocreatine 14 (pH 7.25). Somatic action potentials were elicited by brief current steps (2 nA for 2 ms).

Calcium imaging experiments were performed using Oregon Green BAPTA-1 (100 μm, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Changes in [Ca2+]i associated with bAPs were quantified by calculating ΔF/F, where F is the fluorescence intensity before stimulation, after subtracting autofluorescence, and ΔF is the change in fluorescence during neuronal activity (Lasser-Ross et al. 1991). The emission spectra for OGB-1 indicate that fluorescence signals should remain approximately linear for ΔF/F changes ≤150%. Since all of our recordings were within this range, we are comfortable that we are operating within the linear range of this dye. The autofluorescence of the tissue was measured in a region of equal size adjacent to the dye-filled neuron. Sequential frame rate was 0.5–1 kHz.

For voltage imaging experiments, cells were initially stained by free diffusion of the voltage-sensitive styryl dye JPW 3028 (0.2 mg ml−1, purchased from L. Loew, University of Connecticut, Farmington, CT, USA) from the pipette into the cell body. After 20 min of staining, the patch electrode was removed and neurons were incubated for 1–2 h at room temperature to allow the diffusion of the dye to the dendrites. Stained neurons were then re-patched at 34–36°C with an electrode containing a dye-free solution. Neurons were discarded if the resting membrane potential was more positive than −60 mV, because this would indicate that they had been damaged during the filling procedures. Sequential frame rate was 3 kHz. In both cases the ΔF/F measurements were repeated three to five times and averaged. For the oblique branches, the distance reported was calculated as distance of the branch point from the soma + distance of the examined region along the oblique branch.

Boosting experiments were performed using a dual galvanometer based scanning system to simultaneously image local Ca2+ in the dendrites of CA1 neurons and multiphoton photo-release glutamate at multiple dendritic spines (Prairie Technologies). Neurons were filled with OGB-1 and imaged using a 60× objective (Olympus). Ultra-fast, pulsed, laser light at 930 nm (Mira 900F; Coherent, Auburn, CA, USA) was used to excite the OGB-1 following bAP (generated by somatic current injection), glutamate uncaging or a combination of both. Ultra-fast, pulsed 720 nm laser light (Chameleon, Coherent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to photolyse MNI-caged glutamate (MNI-Glu, Tocris Cookson, Ballwin, MO, USA; 10 mm applied via pipette above slice, Gasparini & Magee, 2006; Losonczy & Magee, 2006).

Data are reported as means ± s.e.m. Statistical comparisons were performed by using Student's t test. Means were considered to be significantly different when P < 0.05.

Results

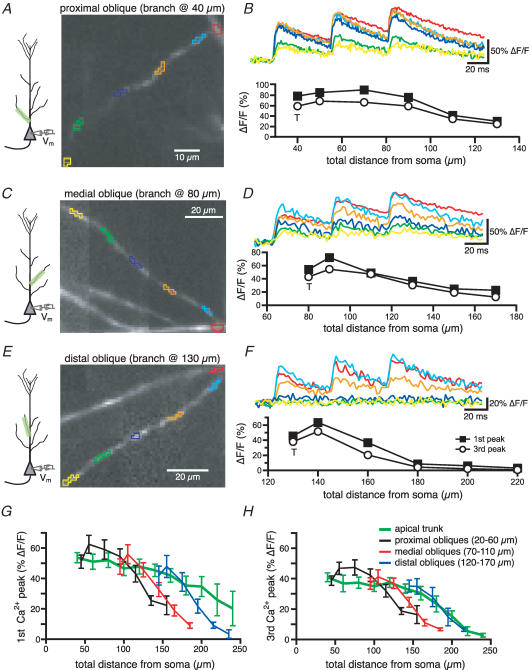

To study the profile of spike back-propagation in radial oblique branches of CA1 pyramidal neurons, we have initially filled neurons with OGB-1 through a somatic patch pipette and characterized the Ca2+ transients associated with bAPs. Figure 1 shows the fluorescence images (left) and the corresponding changes in [Ca2+]i (expressed as ΔF/F, right) associated with a 20 Hz train of three somatic action potentials for different oblique branches emerging at increasing distances from the soma. For the first bAP in a train, the spatial profile of the Ca2+ transients along the oblique branch was biphasic as an initial increase over trunk values (T, probably due to the increase in the surface to volume ratio) was followed by a progressive decrease in the size of the signals as the bAP propagated along the length of a branch (Fig. 1B, D and F). Both the size of the initial increase and its spatial extent decreased with the distance of the branch point from the soma (see the average data in Fig. 1G). Additionally, the decrease in the Ca2+ signal with distance along the length of a branch was more rapid and accentuated for the more distant radial obliques (compare Fig. 1F with 1B). A similar trend was observed for the Ca2+ transients associated with the third spike in the train although the amplitude was generally smaller than that of the first spike at every location. Also, the progressive decrease in Ca2+ transient amplitude during the short train was more pronounced in the distal trunk than in the oblique branches, suggesting that propagation in the distal trunk is relatively more frequency dependent (Fig. 1G and H, Colbert et al. 1997; Jung et al. 1997).

Figure 1. The amplitude of the Ca2+ influx associated with bAP decreases with the distance from the soma in radial oblique branches.

A, CCD image of an OGB-1 filled proximal oblique (branch point at 40 μm). B, Ca2+ influxes generated in response to a 20-Hz-train of three somatic action potentials in the regions of the oblique branches marked by like-coloured boxes in A. Below is the plot of the Ca2+ influx associated with the first and the third spike as a function of the distance from the soma. T is the value of ΔF/F recorded at the trunk in the proximity of the branch point. C and D, same as above for a medial oblique (branch point at 80 μm). E and F, same as A and B for a distal oblique (branch point at 130 μm). The insets in A, C and E show the location of the somatic electrode and the imaged region. G, mean calcium influx associated with the first spike of the train as a function of the total distance from the soma. The ΔF/F values for the oblique branches were binned for proximal (branch point between 20 and 60 μm), medial (branch point between 70 and 110 μm) and distal obliques (emerging between 120 and 170 μm). The values of ΔF/F appeared to decline more steeply for the oblique branches than for the apical dendrites for total distances > 120 μm. H, same as G for the third spike.

The reduction of the amplitude of bAPs in the distal apical dendritic trunks of CA1 neurons is attributed primarily to an increase in the density of transient (A-type) K+ channels at distal locations (Hoffman et al. 1997). To test whether this was also the case for oblique branches, we applied Ba2+ (150 μm) in lieu of the previously used 4-amino-pyridine (4-AP), because the epileptiform activity and calcium plateaus induced by millimolar concentrations of 4-AP interfere with our optical methods (Andreasen & Lambert, 1995; Hoffman et al. 1997; Magee & Carruth, 1999). There are previous reports of a Ba2+-sensitive (200 μm) transient outward K+ current in cardiac myocytes (Li et al. 1998, 2000).

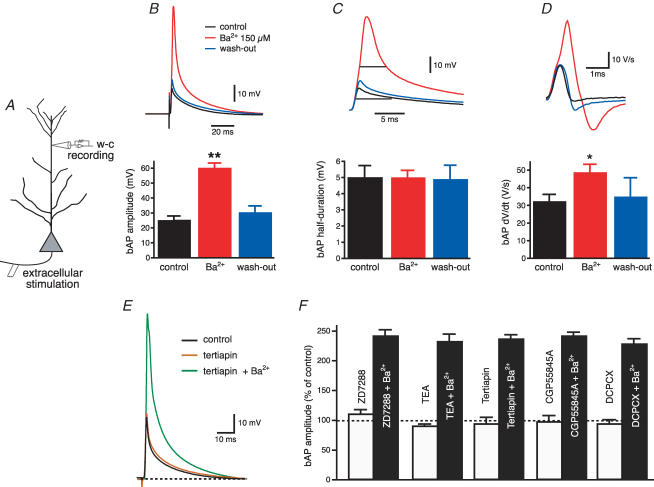

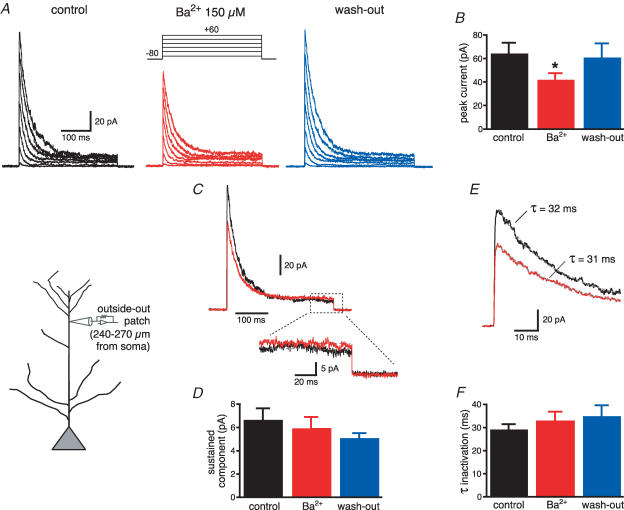

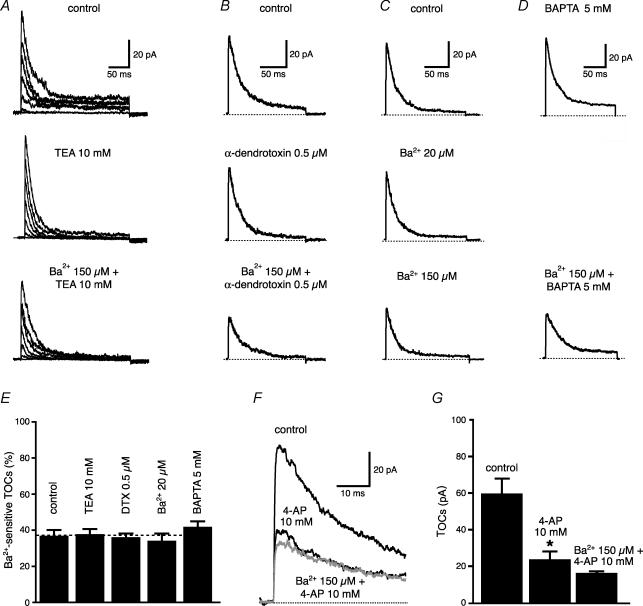

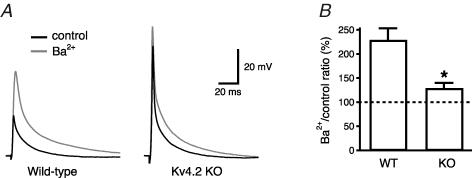

To test for the specificity of Ba2+ (150 μm) block on K+ channels in dendrites, we first antidromically stimulated the axons of CA1 neurons and recorded the amplitude of the bAP with an electrode in current-clamp configuration at a distance of 240–270 μm from the soma (Fig. 2A). This is a region where the bAP amplitude is known to decrease due to the increase in the density of transient K+ channels (Hoffman et al. 1997; Bernard & Johnston, 2003). In these conditions, Ba2+ (150 μm) significantly increased the bAP amplitude (from 25 ± 3 to 60 ± 4 mV, n = 15, P < 0.0001, Fig. 2B) and its maximum rate of rise (from 32 ± 4 to 48 ± 5 V s−1, n = 15, P < 0.01 Fig. 2D). The effect of Ba2+ was fully reversible upon wash-out (30 ± 5 mV, n = 9) and occurred independent of changes in the half-duration of the bAP (control: 5.0 ± 0.8 ms; Ba2+: 5.0 ± 0.9 ms, n = 15, P = 0.47, Fig. 2C). Furthermore, preincubation with blockers of Ih, G-protein-activated inward rectifier K+ channels, delayed-rectifier K+ channels or with antagonists of GABAB and adenosine A receptors did not occlude the effect of Ba2+ on bAP amplitude (Fig. 2E and F). To examine if these effects of Ba2+ (150 μm) on spike back-propagation could be attributed to the block of a transient K+ current such as IA, we performed a set of voltage-clamp experiments in the outside-out patch-clamp configuration. Outside-out patches were pulled from the apical dendrites at the same distance as for the current-clamp experiments (240–270 μm) and K+ currents were activated by 300 ms depolarizing steps at various voltages. Ba2+ (150 μm) significantly reduced the peak of the transient component of the outward current (from 64 ± 9 to 42 ± 5 pA for the step from −80 mV to +60 mV, n = 19, P < 0.01, Fig. 3A and B), without affecting the sustained component, measured at 250–300 ms (from 6 ± 1 to 6 ± 1 pA, P > 0.1, n = 19, Fig. 3C and D). The decrease of the peak current by Ba2+ did not affect the inactivation time constants (from 29 ± 3 to 32 ± 4 ms, P > 0.2, Fig. 3E and F) and was reversible upon wash-out. In addition, the Ba2+ sensitive outward current was insensitive to blockers of delayed rectifiers, Kv1-type, inward-rectifier and Ca2+-activated K+ currents (Fig. 4A–E), but was strongly reduced by 4-AP (10 mm, Fig. 4F and G). Finally, Ba2+ (200 μm) had a significantly (P < 0.01, n = 6) smaller effect on bAP amplitude at similar distances in dendrites from mice lacking the Kv4.2 gene (Fig. 5). There is substantial evidence that the Kv4.2 subunit is largely responsible for the A-type K+ current in these neurons (Yuan & Chen, 2006; Chen et al. 2006).

Figure 2. Ba2+ (150 μm) enhances action potential back-propagation into distal apical dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons.

A, diagram of experimental configuration for whole-cell recordings from distal apical dendrites (240—270 μm from the soma). B, Ba2+ increases the amplitude of back-propagating action potentials elicited by antidromic stimulation of the axons of CA1 pyramidal neurons, without affecting the half-width (C). D, Ba2+ significantly increased the maximal rate of rise of the bAPs recorded from distal apical dendrites. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.0001. E, the G-protein-activated inward-rectifier K+ (GIRK) channel blocker tertiapin (200 nm) has no effect on bAP amplitude, whereas subsequent application of Ba2+ (150 μm) in the presence of tertiapin enhances back-propagation. F, summary bar graph showing that preincubation with Ih blocker (ZD72288, 20 μm, n = 3), delayed rectifier K+ channel blocker (TEA, 10 mm, n = 3), GIRK channel blocker (tertiapin, 200 nm, n = 6), GABAB receptor antagonist (CGP55845A, 1 μm, n = 2) or adenosine A receptor antagonist (DCPCX, 4 μm, n = 3) could not occlude the effect of Ba2+ (150 μm) on AP back-propagation.

Figure 3. Ba2+-sensitive transient outward currents are expressed in distal apical dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons.

A, outside-out patches from distal apical dendrites (see inset) were voltage clamped at −80 mV and depolarized to various potentials in the presence of TTX (0.5 μm) to isolate the activity of K+ channels. Ba2+ (150 μm) partially reduced the peak current (see the average plot in B). C, superimposed traces for the step from −80 to +60 mV to show the effect of Ba2+ (red traces) on the transient and the sustained components (shown expanded below). D, mean data show that Ba2+ does not affect the sustained K+ current. E, expanded traces to show the exponential fitting of the decaying phase for the transient K+ current. F, Ba2+ does not affect the time constant of inactivation of the transient K+ current. *P < 0.01

Figure 4. Ba2+-sensitive TOCs are insensitive to various K+ blockers.

K+ blockers used: TEA 10 mm for delayed-rectifier (n = 9, A), α-dendrotoxin (500 nm) for Kv1-type (n = 6, B), Ba2+ (20 μm) for inward-rectifier (n = 4, C) and intracellular BAPTA 5 mm for Ca2+-sensitive K+ channel (n = 6, D). E, summary plot of the effect of various K+ channel blockers on TOCs. F, when added to 4-AP (10 mm), Ba2+ has almost no effect, suggesting that they block the same outward current. G, summary plot from F (n = 6).

Figure 5. Deletion of the Kv4.2 gene led to significant reduction of the Ba2+ (200 μm) effect on bAP amplitude in the apical dendrites.

A, whole-cell recordings made from approximately 250 μm in apical dendrites of Kv4.2 KO mice and littermate controls. B, the ratio between the bAP amplitude recorded in Ba2+ and in control was significantly (P < 0.01) different for KO mice (128 ± 11%, n = 6) with respect to wild-type littermates (228 ± 23%, n = 6).

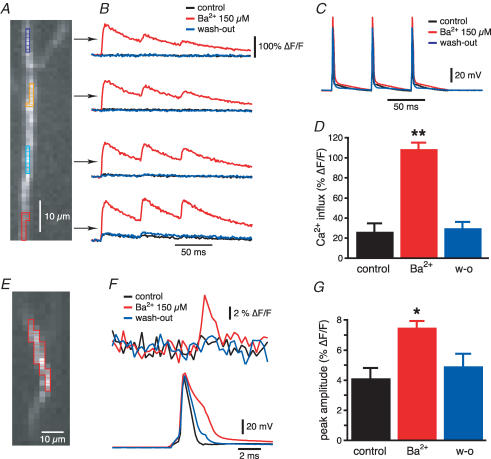

We then compared the effect of Ba2+ (150 μm) on the electrically recorded bAPs (Fig. 2A) with those measured optically using calcium and voltage indicators. Figure 6A shows a region of distal (> 250 μm) apical dendrite from a CA1 pyramidal neuron filled with Oregon Green BAPTA-1. A train of three action potentials at 20 Hz was evoked by 2 ms current injections of 2 nA into the soma (Fig. 6C). In control conditions, only the more proximal locations (∼250 μm from the soma) showed a measurable Ca2+ signal, while for the more distal locations the Ca2+ signal associated with the bAP was not distinguishable from the baseline noise. In agreement with the dendritic electrical recordings (Fig. 2), Ba2+ increased the amplitude of the Ca2+ transients associated with the bAP at every trunk location (Fig. 6B). In particular, Ba2+ (150 μm) increased the Ca2+ transient induced by the first action potential at 250 μm from the soma from 26 ± 9% to 108 ± 7% (n = 5, P < 0.005, Fig. 6D). Ba2+ also caused somatic action potentials to broaden (Fig. 6F), possibly due to a partial block of the Ca2+-activated K+ channels that participate in somatic AP repolarization (Lancaster & Adams, 1986; Storm, 1987; Chiba & Marcus, 2000). These channels, however, do not appear to regulate dendritic AP duration (Poolos & Johnston, 1999).

Figure 6. Optical imaging data from distal apical dendrites are in agreement with electrophysiological bAP recordings.

A, distal portion of the apical dendrite of a CA1 pyramidal neuron filled with Oregon Green BAPTA-1 (100 μm). B, optical recordings of the Ca2+ influx (expressed as ΔF/F) generated in response to the voltage signal in C in the regions of interest marked in A. Ba2+ reversibly increased the amplitude of the Ca2+ signal associated with the bAP. D, average data of the Ba2+-induced increase in the Ca2+ influx in distal apical dendrites at 270 μm from the soma. E, CCD image of a JPW 3028-filled distal apical dendrite. F, voltage signal (above) obtained from the region of interest highlighted in E in response to a somatic action potential (below). G, mean data of the Ba2+-induced increase of the voltage signal in distal apical dendrites at 270 μm. *P < 0.005, **P < 0.0001.

We then directly measured the voltage changes associated with spike back-propagation by using a voltage sensitive dye, JPW 3028 (0.2 mg ml−1, the area highlighted in Fig. 6E was at ∼270 μm from the soma). In this case, only one somatic spike was generated to avoid prolonged light exposure and photo-damage. In control conditions, the voltage signal in the distal trunk was undetectable from the baseline noise, but in the presence of Ba2+ a significant peak was observed with a latency of about 2–3 ms from the somatic spike (Fig. 6F). On average, Ba2+ nearly doubled the voltage signal measured at 250–280 μm from the soma (from 4.1 ± 0.7% to 7.4 ± 0.4%, n = 7, P < 0.05, Fig. 6g), similarly to what was observed with the electrophysiological recordings (see Fig. 2B). These data confirm that these optical imaging methods reliably reproduce the changes in bAP amplitude observed with electrophysiological recordings and can thus be used to investigate the properties of spike back-propagation in radial oblique branches.

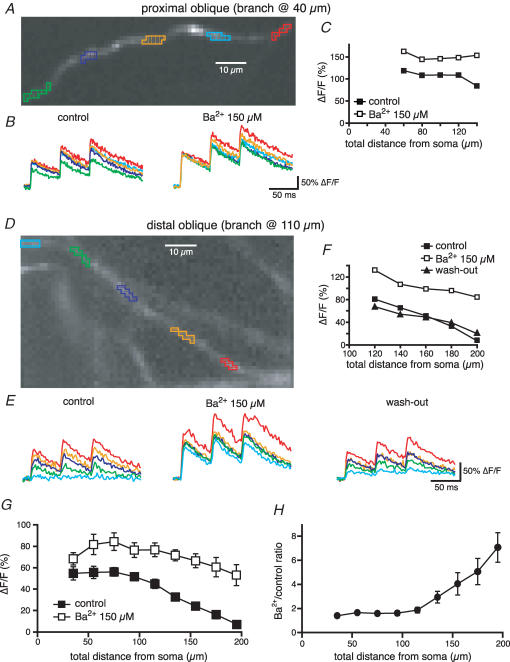

We then tested the hypothesis that an increase in the density of transient K+ channels in the distal portions of oblique dendrites could determine the decrease in amplitude of the bAP shown previously (see Fig. 1). The effect of Ba2+ on the Ca2+ transients associated with the bAPs for a proximal and a distal oblique is illustrated in Fig. 7. In control conditions, the Ca2+ signal for the proximal oblique was approximately constant for the first 60 μm after the branch point and started declining only after 80 μm (at a total length of ∼150 μm). In this cell, Ba2+ produced a slight increase (∼30%) of the Ca2+ signal in the more proximal portion of the oblique and greatly reduced the decay with the distance (Fig. 7A–C). In the more distal oblique the Ca2+ transients decreased monotonically from the branch point, becoming almost undetectable at a total distance of 200 μm from the soma. The effect of Ba2+ on back-propagation in this region of the dendrite was greater than that of the proximal obliques, such that in the presence of Ba2+ there was only a slight decrease of the Ca2+ transients with the distance from the soma (Fig. 7D–F).

Figure 7. Ba2+ reduces the distance-dependent decrease in the Ca2+ influx associated with bAP in radial oblique branches.

A, OGB-1 filled proximal oblique (branch point at 40 μm) from a CA1 pyramidal neuron. B, optical recordings of the Ca2+ influx generated in response to a 20 Hz train of three somatic action potentials in the regions of the oblique branches marked by like-coloured boxes in A in control conditions and in the presence of Ba2+ (150 μm). C, ΔF/F associated with the first spike as a function of the distance from the soma for the oblique branch in A. D, E and F, as above but for a distal radial oblique (branch point at 110 μm). G, mean data for the Ca2+ influx associated with the first bAP as a function of the total distance from the soma in control conditions and in the presence of Ba2+. The effect of Ba2+ is larger for more distal oblique locations, where the Ca2+ influx was reduced in control conditions, as clear from the plot of the ratio in H.

We next determined the effect of Ba2+ on optically measured bAPs in the radial oblique branches. As for the Ca2+ imaging experiments, the effect of Ba2+ was highly dependent upon the oblique location. For proximal obliques (total distance of < 100 μm) the voltage signal in control conditions was usually 7–8%; Ba2+ did not affect the amplitude but increased the half-width (Fig. 8A and B), similar to what was observed with the somatic recordings (Fig. 8C). On the other hand, the voltage signal for the distal obliques was often indistinguishable from the baseline noise, but Ba2+ induced the appearance of a voltage peak (Fig. 8D–F). Once again, the average plot in Fig. 8G shows a decrease of the voltage signal as a function of the total distance from the soma in control conditions (branch points for these radial obliques ranged between 60 and 140 μm from the soma). Ba2+ almost completely countered this decreasing trend, except for the most distal locations (∼200 μm, Fig. 8G). This could be due either to an only partial block of the transient K+ channel by Ba2+ in the distal obliques or a slight decrease in the density of Na+ channels at these locations.

Figure 8. Ba2+ reduces the distance-dependent decrease of the voltage signal associated with bAP in radial obliques.

A, CCD image of a JPW 3028-filled proximal radial oblique branch (emerging at 40 μm). B, voltage signals recorded following the somatic action potentials (C) in the two regions highlighted in A in control conditions, in the presence of Ba2+ and upon wash-out. D, E and F, as above for the distal portion of an oblique radial branch. G, mean plot of the voltage signal as a function of the total distance from the soma. As for the Ca2+ influx, the effect of Ba2+ is greater for distal regions of the radial oblique branches, as clear from the plot of the ratio in H.

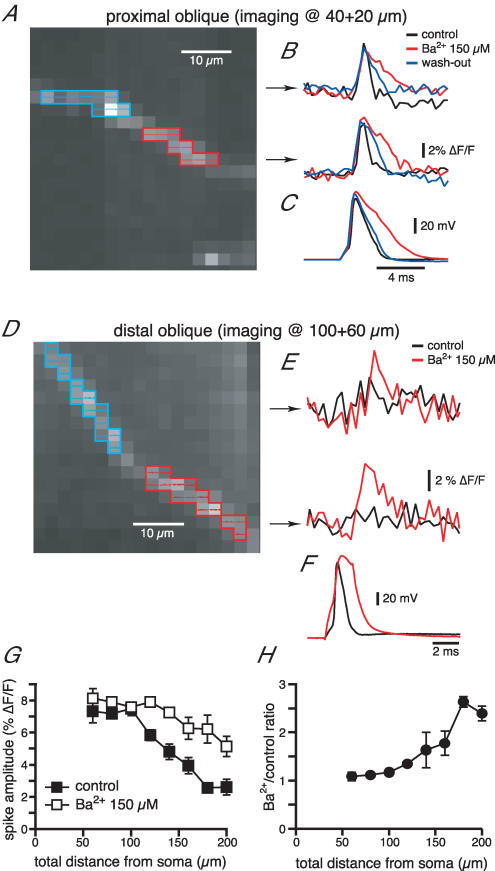

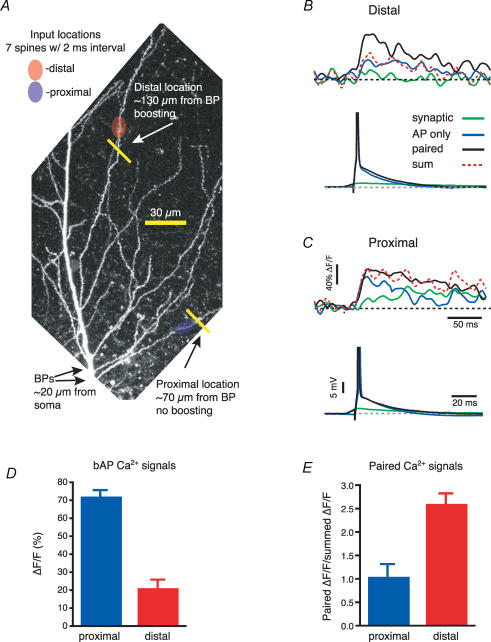

Taken together these data suggest that the amplitude of the bAPs in oblique branches decreases with distance from the soma because of an enhanced contribution of transient K+ currents to bAP amplitude, possibly due to an elevated transient K+ current density. If this is the case, the bAPs in the distal oblique branches should be boosted by a concomitant dendritic depolarization, as has been shown in the distal apical trunk of CA1 pyramidal neurons (Magee & Johnston, 1997; Stuart & Häusser, 2001). To test this, synaptic-like stimulation was produced by two-photon uncaging of MNI-glutamate in an asynchronous but spatially clustered input pattern (10 uncagings with an interval of 2–4 ms at spines spread over 20–30 μm, Losonczy & Magee, 2006) and this was paired with axonal action potential generation (3–5 ms somatic current injection). The local Ca2+ signals were recorded by line scanning regions of the oblique dendrites contiguous to, but not within, the uncaging regions (∼20 μm away from input site) at different distances from the soma (average total distance: proximal, 97 ± 8 μm, distal, 159 ± 4 μm, Fig. 9A–C). The occurrence of boosting was assessed by dividing the amplitude of the Ca2+ signals obtained with pairing of bAPs and MNI-glutamate uncaging by the arithmetic sum of the two delivered separately (Fig. 9B, C and E). Confirming the results obtained with the high-speed confocal imaging, we found that the amplitude of the Ca2+ signal associated with bAPs decreased with the distance from the soma (proximal: 70 ± 3%, n = 5; distal: 21 ± 5% ΔF/F, n = 7, P = 0.001, Fig. 9D) while the local glutamate uncaging produced comparable Ca2+ transients in both regions (proximal: 13 ± 5% ΔF/F, n = 5; distal: 9 ± 3% ΔF/F, n = 7, P = 0.4). In proximal regions, pairing of bAPs and glutamate uncaging produced signals that were similar in amplitude to the sum of the two independent signals (85 ± 5% ΔF/F, 102% of arithmetic sum, n = 5). On the other hand, the paired signals were much larger than the summation of the two independent signals in distal locations (71 ± 9% ΔF/F, 261% of arithmetic sum, n = 7). These data indicate that an asynchronous synaptic stimulation could boost the bAPs in the most distal regions of the radial oblique branches to such a degree that the Ca2+ signals associated with them were similar in amplitude to those recorded in the more proximal oblique regions (85% versus 71%; P = 0.15).

Figure 9. bAP amplitude in the distal obliques can be boosted by asynchronous synaptic stimulation.

A, two photon image stack of the apical trunk and the surrounding oblique branches filled with OGB-1 (100 μm) to show two uncaging and imaging locations. Arrows labelled ‘BPs’ point to the locations where both oblique dendrites branch off from the trunk. B, local Ca2+ transients recorded at the distal location in A for the bAP (blue), the MNI-glutamate asynchronous uncaging (green) and the combination of the two (black). The red dotted line represents the arithmetic sum of the signals obtained during the bAP and the synaptic stimulation. C, as B but for the proximal location. The traces below show the somatic recordings. APs are truncated. D, the plot of the Ca2+ influx for the back-propagating spikes shows a marked decrease with the distance from the soma (proximal = 97 ± 8 μm; distal = 159 ± 4 μm). E, only the distal locations show a significant boosting (expressed as paired ΔF/F/summed ΔF/F) of the bAP by MNI-glutamate uncaging.

Discussion

In this work we have further characterized the features of action potential back-propagation into radial oblique branches. The main observations were as follows. First, oblique branch bAP amplitude remained initially constant and then decreased with distance along oblique branches. Second, the length for which bAP amplitude remained constant within a branch depended on the distance of the branch-point from the soma, such that propagation was progressively weaker for more distant branches. Third, the bAP-associated Ca2+ transients were biphasic, increasing initially just after the branch point but quickly decreasing as bAP amplitude decreased. The extent of the increase shows a similar dependence on branch-point location. Fourth, the distance-dependent decrease in bAP amplitude and Ca2+ peaks within a branch required the presence of a Ba2+ sensitive current (presumably carried by Kv4.2-encoded A-type K+ channels). Fifth, appropriately timed branch depolarization could overcome the inhibitory influence of branch K+ channels on bAPs through voltage-dependent inactivation. These data extend our previous observations concerning radial oblique action potential back-propagation (Frick et al. 2003). Our improved optical methods and the use of a more selective blocker allowed us to more directly compare bAP amplitude within a given oblique branch and to measure bAP associated Ca2+ transients within branches at a greater level of spatial and temporal accuracy. In particular, we could extend the analysis to more distal portions of the oblique branches, which typically were not resolvable with the previous imaging methods. In addition, we observed an initial increase of the Ca2+ transients in the oblique branches just after the branch-point, in agreement with multiphoton experiments in Frick et al. (2003). Together, as detailed below, these studies indicate that single unpaired bAPs could provide oblique branches with a relatively accurate distance-dependent signal that, when paired with appropriately timed input, could be transformed into a signal useful for the induction of associative dendritic and synaptic plasticity.

Mechanisms shaping oblique branch bAP propagation

The overall propagation profile in the oblique branches could be consistent either with a decrease of Na+ channel density or an increase of K+ channels in the oblique branches. That removal of certain amounts of K+ channels, through either pharmacological blockade or depolarization-induced inactivation (pairing), could produce full amplitude bAPs within regions that under control conditions were quite reduced supports the presence of Na+ channels throughout the arbor. The decrease of bAP amplitude with distance down a branch seems to indicate that K+ channel density is higher in the oblique than the trunk region where the branch-point occurred. This idea fits well with a recent multicompartmental model that used an A-type K+ channel density increased threefold above that of the trunk region near the branch point to produce a similar propagation profile (Migliore et al. 2005). However, our data do not exclude an increase in the expression of transient K+ channels along the oblique branches. A higher density of these channels, only partially blocked by Ba2+, could explain why bAP amplitude in the most distal obliques was still smaller during Ba2+ perfusion (Fig. 6G). However, this result could also be explained by a decrease of Na+ channels near the branch ends. Together the data lead us to propose that most branch regions contain a uniform Na+ channel density while A-type K+ channel density within each branch is significantly elevated above that of the trunk region where the oblique branch originates. Additional experiments and computational modelling will be required to clarify these aspects.

Functional significance

These data suggest two functions for bAPs. First, the back-propagation of unassociated low frequency action potentials into the different branches creates a Ca2+ signal that, because of the marked distance dependence, is an accurate indicator of synapse and dendrite location relative to the output site. This Ca2+ influx could act on local biochemical signalling pathways to tonically regulate the density and properties of the various channels within the dendrite itself, as well as the synapses located on the branch, to produce the location dependencies of H, Na+, K+, AMPAR and GlyR channels found at steady-state in many central neurons (Hoffman et al. 1997; Colbert et al. 1997; Jung et al. 1997; Alvarez et al. 1997; Magee, 1998; Smith et al. 2003; Gasparini & Magee, 2002; Nicholson et al. 2006).

Second, the rapid decrease in amplitude down the oblique branches, particularly for high frequency APs, allows coincident synaptic input to regulate the amplitude of the bAP as long as the input is sufficient in number and timing to produce adequate branch depolarization. The large Ca2+ influx produced by unblocked NMDAR within the activated synapses provides an associative signal that is important for the induction of synaptic and dendritic plasticity within those branches achieving the proper associations (for neocortical neurons see Nevian & Sakmann, 2006). That similarly sized Ca2+ transients are achieved during pairing at both proximal and distal radial oblique locations suggests that the bAP is capable of functioning as an effective associative feedback signal for all Schaffer collateral synapses. Future studies are needed to determine if this holds true for the perforant path synapses located in the more distal tuft regions of CA1 pyramidal neurons.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Institute of Health (CoBRE NCRR P20 RR16816 to S.G.; NS37444, NS48432 and MH44754 to D.J.; NS39458 to J.C.M.). We thank Dejan Zecevic for his help in the initial experiments with the voltage-sensitive dyes and the gift of some JPW 3028.

References

- Alvarez FJ, Dewey DE, Harrington DA, Fyffe RE. Cell-type specific organization of glycine receptor clusters in the mammalian spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1997;379:150–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrasfalvy BK, Magee JC. Changes in AMPA receptor currents following LTP induction on rat CA1 pyramidal neurones. J Physiol. 2004;559:543–554. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.065219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen M, Lambert JD. Regenerative properties of pyramidal cell dendrites in area CA1 of the rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 1995;483:421–441. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antic S, Major G, Zecevic D. Fast optical recordings of membrane potential changes from dendrites of pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:1615–1621. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.3.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antic S, Zecevic D. Optical signals from neurons with internally applied voltage-sensitive dyes. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1392–1405. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01392.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister NJ, Larkman AU. Dendritic morphology of CA1 pyramidal neurones from the rat hippocampus. I. Branching patterns. J Comp Neurol. 1995a;360:150–160. doi: 10.1002/cne.903600111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister NJ, Larkman AU. Dendritic morphology of CA1 pyramidal neurones from the rat hippocampus. II. Spine distributions. J Comp Neurol. 1995b;360:161–171. doi: 10.1002/cne.903600112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard C, Johnston D. Distance-dependent modifiable threshold for action potential back-propagation in hippocampal dendrites. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:1807–1816. doi: 10.1152/jn.00286.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yuan L-L, Zhao C, Birnbaum SG, Frick A, Jung WE, Schwarz TL, Sweatt JD, Johnston D. Deletion of Kv4.2 gene eliminates dendritic A-type K+ current and enhances induction of long-term potentiation in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12143–12151. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2667-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba T, Marcus DC. Nonselective cation and BK channels in apical membrane of outer sulcus epithelial cells. J Membr Biol. 2000;174:167–179. doi: 10.1007/s002320001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert CM, Johnston D. Axonal action-potential initiation and Na+ channel densities in the soma and axon initial segment of subicular pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6676–6686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06676.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert CM, Magee JC, Hoffman DA, Johnston D. Slow recovery from inactivation of Na+ channels underlies the activity-dependent attenuation of dendritic action potentials in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6512–6521. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06512.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Fricker D, Brager DH, Chen X, Lu HC, Chitwood RA, Johnston D. Activity-dependent decrease of excitability in rat hippocampal neurons through increases in Ih. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1542–1551. doi: 10.1038/nn1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick A, Magee J, Johnston D. LTP is accompanied by an enhanced local excitability of pyramidal neuron dendrites. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:126–135. doi: 10.1038/nn1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick A, Magee J, Koester HJ, Migliore M, Johnston D. Normalization of Ca2+ signals by small oblique dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3243–3250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03243.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini S, Magee JC. Phosphorylation-dependent differences in the activation properties of distal and proximal dendritic Na+ channels in rat CA1 hippocampal neurons. J Physiol. 2002;541:665–672. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.020503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini S, Magee JC. State-dependent dendritic computation in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2088–2100. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4428-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heynen AJ, Quinlan EM, Bae DC, Bear MF. Bidirectional, activity-dependent regulation of glutamate receptors in the adult hippocampus in vivo. Neuron. 2000;28:527–536. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DA, Magee JC, Colbert CM, Johnston D. K+ channel regulation of signal propagation in dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Nature. 1997;387:869–875. doi: 10.1038/43119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Vervaeke K, Storm JF. Two forms of electrical resonance at theta frequencies, generated by M-current, h-current and persistent Na+ current in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Physiol. 2002;545:783–805. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.029249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HY, Mickus T, Spruston N. Prolonged sodium channel inactivation contributes to dendritic action potential attenuation in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6639–6646. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06639.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster B, Adams PR. Calcium-dependent current generating the afterhyperpolarization of hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1986;55:1268–1282. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.55.6.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser-Ross N, Miyakawa H, Lev-Ram V, Young SR, Ross WN. High time resolution fluorescence imaging with a CCD camera. J Neurosci Meth. 1991;36:253–261. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90051-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Sun H, Nattel S. Characterization of a transient outward K+ current with inward rectification in canine ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 1998;274:C577–C585. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.3.C577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Yang B, Sun H, Baumgarten C. Existence of a transient outward K+ current in guinea pig cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H130–H138. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.1.H130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losonczy A, Magee JC. Integrative properties of radial oblique dendrites in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Neuron. 2006;50:291–307. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC. Dendritic hyperpolarization-activated currents modify the integrative properties of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7613–7624. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07613.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC. Voltage-gated ion channels in dendrites. In: Stuart G, Spruston S, Hausser M, editors. Dendrites. 1999. pp. 139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC. Dendritic integration of excitatory synaptic input. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000;1:181–190. doi: 10.1038/35044552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Carruth M. Dendritic voltage-gated ion channels regulate the action potential firing mode of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:1895–1901. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.4.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Johnston D. A synaptically controlled, associative signal for Hebbian plasticity in hippocampal neurons. Science. 1997;275:209–213. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Johnston D. Plasticity of dendritic function. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megias M, Emri Z, Freund TF, Gulyas AI. Total number and distribution of inhibitory and excitatory synapses on hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. Neuroscience. 2001;102:527–540. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliore M, Ferrante M, Ascoli GA. Signal propagation in oblique dendrites of CA1 pyramidal cells. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:4145–4155. doi: 10.1152/jn.00521.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevian T, Sakmann B. Spine Ca2+ signaling in spike-timing-dependent plasticity. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11001–11013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1749-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson DA, Trana R, Katz Y, Kath WL, Spruston N, Geinisman Y. Distance-dependent differences in synapse number and AMPA receptor expression in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Neuron. 2006;50:431–442. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poolos NP, Johnston D. Calcium-activated potassium conductances contribute to action potential repolarization at the soma but not the dendrites of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5205–5212. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05205.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Ellis-Davies GC, Magee JC. Mechanism of the distance-dependent scaling of Schaffer collateral synapses in rat CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2003;548:245–258. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.036376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruston N, Schiller Y, Stuart G, Sakmann B. Activity-dependent action potential invasion and calcium influx into hippocampal CA1 dendrites. Science. 1995;268:297–300. doi: 10.1126/science.7716524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm JF. Action potential repolarization and a fast after-hyperpolarization in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Physiol. 1987;385:733–759. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GJ, Häusser M. Dendritic coincidence detection of EPSPs and action potentials. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:63–71. doi: 10.1038/82910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GJ, Sakmann B. Active propagation of somatic action potentials into neocortical pyramidal cell dendrites. Nature. 1994;367:69–72. doi: 10.1038/367069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Schiller J, Sakmann B. Action potential initiation and propagation in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 1997;505:617–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.617ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan LL, Chen X. Diversity of potassium channels in neuronal dendrites. Prog Neurobiol. 2006;78:374–389. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]