Abstract

The substantia gelatinosa (lamina II) of the spinal dorsal horn contains inhibitory and excitatory interneurons that are thought to play a critical role in the modulation of nociception. However, the organization of the intrinsic circuitry within lamina II remains poorly understood. We used glutamate uncaging by laser scanning photostimulation to map the location of neurons that give rise to local synaptic inputs to islet cells, a major class of inhibitory interneuron in lamina II. We also mapped the distribution of sites on the islet cells that exhibited direct (non-synaptic) responses to uncaging of excitatory and inhibitory transmitters. Local synaptic inputs to islet cells arose almost entirely from within lamina II, and these local inputs included both excitatory and inhibitory components. Furthermore, there was a striking segregation in the location of sites that evoked excitatory versus inhibitory synaptic inputs, such that inhibitory presynaptic neurons were distributed more proximal to the islet cell soma. This was paralleled in part by a differential distribution of transmitter receptor sites on the islet cell, in that inhibitory sites were confined to the peri-somatic region while excitatory sites were more widespread. This differential organization of excitatory and inhibitory inputs suggests a principle for the wiring of local circuitry within the substantia gelatinosa.

Lamina II (substantia gelatinosa) of the spinal dorsal horn contains a high density of excitatory and inhibitory interneurons that are thought to be critically involved in the modulation of nociception. Lamina II neurons receive major primary afferent input from fine myelinated A-delta and unmyelinated C fibres, and many respond to noxious peripheral stimuli (Kumazawa & Perl, 1978; Light et al. 1979; Bennett et al. 1980; Woolf & Fitzgerald, 1983; Yoshimura & Jessell, 1989). They also receive descending inputs from multiple neurotransmitter systems that exert powerful modulatory influences on nociceptive transmission (Light et al. 1986; Millan, 2002; Kato et al. 2006). Because of its critical role in the transmission and modulation of nociception, lamina II has been the subject of intensive study that has characterized in great detail the anatomical and physiological properties of its neurons (Grudt & Perl, 2002). However, one aspect of lamina II organization that has proven particularly difficult to elucidate is the pattern of local connectivity, both within lamina II as well as between lamina II and other dorsal horn laminae. Much of the primary afferent input to lamina II neurons is polysynaptic (Yoshimura & Nishi, 1992, 1995; Narikawa et al. 2000), and therefore probably mediated by local interneuronal connections. Anatomical study shows that lamina II neurons have major axonal projections within the superficial laminae (I and II) of the dorsal horn (Bennett et al. 1980), as well as projections to deeper laminae (Light & Kavookjian, 1988; Eckert et al. 2003). Thus, it appears that lamina II neurons participate in a substantial degree of local synaptic connectivity that is critical to their role in dorsal horn function.

Recently, in a major advance for the understanding of dorsal horn organization, Lu & Perl (2003, 2005) used the approach of simultaneous recording from pairs of neurons to examine patterns of functional connectivity within the superficial dorsal horn. They were able to demonstrate the presence of an inhibitory monosynaptic projection within lamina II from islet neurons to central neurons, and excitatory projections from central neurons to vertical neurons, as well as from vertical neurons to lamina I neurons. These studies were necessarily restricted to examining connections between neurons that were within a distance of 250 μm, in order to maximize the chance of finding a connected pair. The yield with this approach tends to be relatively low because only a small percentage of two randomly chosen neurons actually prove to be synaptically connected, and it is not feasible to sample systematically over larger areas.

An alternative approach to studying local circuitry that can potentially complement the information obtained with paired recordings is laser scanning photostimulation (LSPS), in which whole-cell patch-clamp recording in the slice preparation is used to record synaptic responses to photostimulation-induced uncaging of caged glutamate (Callaway & Katz, 1993; Katz & Dalva, 1994; Callaway & Yuste, 2002). This method provides a way to map the locations of neurons that project locally to a single identified neuron, and also allows the identification of such projections as excitatory or inhibitory. This approach has been used to reveal new aspects of functional organization of local circuitry in cerebral cortex as well as other brain regions that could not be obtained with any other available approaches (e.g. Dalva & Katz, 1994; Sawatari & Callaway, 1996; Pettit et al. 1999; Schubert et al. 2001; Shepherd et al. 2003; Kim & Kandler, 2003; Helms et al. 2004). The present study used LSPS for the first time in the spinal cord to examine the organization of local synaptic inputs to islet cells, the major known class of inhibitory interneuron in lamina II. Islet cells have dendrites that are the longest of any class of lamina II neuron and exhibit the predominantly sagittal orientation that is characteristic of the lamina II neuropil (Szentagothai, 1964; Todd & Lewis, 1986; Grudt & Perl, 2002). (The cell type referred to here is distinct from the population of similarly shaped but smaller cells that have been termed either central cells (Grudt & Perl, 2002) or small islet cells (Todd & McKenzie, 1989; Spike & Todd, 1992; Eckert et al. 2003) by different investigators.) Islet cells typically contain GABA, and a subset of these co-localize glycine (Todd & Sullivan, 1990; Spike & Todd, 1992). The paired recording studies of Lu & Perl (2003) described inhibitory projections from islet cells, but did not identify any local inputs to islet cells. Our present results with LSPS demonstrate a differential distribution of the local neurons that provide excitatory and inhibitory inputs to islet cells that is paralleled in part by a differential distribution of neurotransmitter receptor sites on the islet cells. This differential wiring of excitatory and inhibitory inputs may reflect a principle for the organization of local circuitry in the substantia gelatinosa.

Methods

Slice preparation

All experimental procedures involving the use of animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. The methods used for obtaining spinal cord slices from rats were similar to those previously described (Bentley & Gent, 1994). Parasagittal spinal cord slices (250 μm in thickness) were prepared from the lumbar spinal cords of urethane-anaesthetized rats (1.2–1.5 g kg−1i.p.) at the postnatal age of 21–38 days. The rats were killed by exsanguination immediately after spinal cord removal. The slice was transferred to a recording chamber and placed on the stage of an upright microscope equipped with an infrared differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) system, and perfused continuously at a flow rate of 10–20 ml min−1 with Krebs solution equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The Krebs solution was maintained at room temperature for 1 h and was then warmed to 36 ± 1°C prior to recording. The Krebs solution contained (mm): NaCl 117, KCl 3.6, CaCl2 2.5, MgCl2 1.2, NaH2PO4 1.2, NaHCO3 25, and glucose 11. The flow was induced by a peristaltic pump through a polyethylene tube. In each experiment, the circulating Krebs solution contained one of the following three caged compounds, each of which was used at a concentration of 100 μm: 4-methoxy-7-nitroindolinyl-caged l-glutamate (MNI-caged-l-glutamate) (Tocris, St Ellisville, MO, USA), γ-aminobutyric acid (a-carboxy-2-nitrobenzyl) ester, trifluoroacetic acid (O-(CNB-caged) GABA) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) and glycine (O-carboxy-2-nitrobenzyl) ester ((CNB-caged) glycine) (Molecular Probes).

Recording

Laminar regions were identified under a 10 × water-immersion objective (Fig. 1A). Recordings were performed under visual guidance; individual neurons were visualized with a 40 × water-immersion objective. The patch pipettes were filled with a solution containing (mm): potassium gluconate 136, KCl 5, CaCl2 0.5, MgCl2 2, EGTA 5, Hepes 5, and Mg-ATP 5 for recording voltages in the current-clamp mode and excitatory inward currents in the voltage-clamp mode; Cs2SO4 110, TEA-Cl 5, CaCl2 0.5, MgCl2 2, EGTA 5, Hepes 5 and Mg-ATP 5 for recording inhibitory outward currents in the voltage-clamp mode. The tip resistance of the patch pipette was 6–8 MΩ. Whole-cell recordings were obtained from neurons at a depth of 40–80 μm in the slice. A fluorescent dye (Alexa Fluor 488 hydrazide, sodium salt, 10 μm; Molecular Probes) was added to the pipette solution in order to visualize the recorded neuron during the recording periods (Fig. 1B). Neurobiotin (0.1%, Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA) was also added for further anatomical examination following histological processing (Fig. 1C). Mammalian lamina II neurons can be classified into four major groups (islet, central, radial and vertical cells) in parasagittal sections (Grudt & Perl, 2002). Lamina II neurons were classified as islet cells if their dendritic trees extended > 400μm rostrocaudally, as visualized by fluorescence or neurobiotin staining (Grudt & Perl, 2002). This classification criterion excludes the central cells, which have a similar orientation but smaller dimensions, and are referred to by some investigators as small islet cells (Todd & McKenzie, 1989; Spike & Todd, 1992; Eckert et al. 2003). Signals were amplified and filtered at 4 kHz (Multiclamp 700B, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA) and sampled at 10 kHz. The data were digitized with an analog-to-digital converter (Digidata 1322A, Axon Instruments) and stored on a personal computer using a data acquisition program (Clampex version 9.2, Axon Instruments).

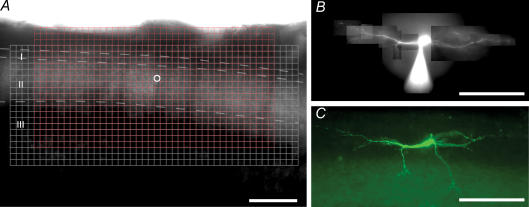

Figure 1. Photostimulation grid and identification of the recorded neuron.

A, photograph of an unfixed parasagittal spinal cord slice imaged by IR-DIC. The small (red, 800 sites in a 15 × 30 array, 25 μm spacing) and large (white, 960 sites in a 20 × 48 array, 25 μm spacing) grids indicate the scanning area for mapping profiles of APs and synaptic responses, respectively. Mapping of direct responses to GABA was done with the smaller grid. White circle indicates the position of the recorded neuron. B, photograph of an islet cell viewed under fluorescence illumination in an unfixed slice following intracellular filling with Alexa Fluor 488. The tip of the micropipette is also visible. C, photograph of the same islet cell as shown in B following histological staining for neurobiotin. Scale bars, 200 μm.

Recording of action potentials (APs) was done under current clamp. Recording of synaptic and direct responses to photostimulation was done under voltage clamp. Excitatory and inhibitory synaptic responses were recorded in separate experiments. Excitatory (inward) currents were recorded at a holding potential of −70 mV. This potential was close to the reversal potential for GABAA- and glycine-mediated responses, so IPSCs were minimized and usually undetectable. Inhibitory (outward) currents were recorded at a holding potential of 0 mV. At this potential, inward EPSCs mediated by glutamate receptors were minimized and usually undetectable. This holding potential was used both for recording of IPSCs and, in separate experiments, for recording of direct responses to uncaging of GABA. An additional set of experiments was carried out to record direct GABAergic responses at the same holding potential that was used for the recording of glutamatergic responses (−70 mV). For these experiments, a high-chloride internal solution was used in the recording pipette to make the chloride reversal potential more positive, so that GABA-evoked responses would appear as large inward currents (see Discussion). This solution contained (mm): KCl 141, CaCl2 0.5, MgCl2 2, EGTA 5, Hepes 5, and Mg-ATP 5. To isolate GABAergic inward currents from spontaneous EPSCs, 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX, 10 μm; Tocris) and dl-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV, 25 μm; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) were added to the Krebs bathing solution. Membrane potentials were not corrected for the liquid junction potential between the Krebs and patch-pipette solutions.

Laser scanning photostimulation

The laser and associated optical apparatus for delivering the beam to the specimen were obtained from Prairie Technologies (Middleton, WI, USA). The light source was a Coherent Enterprise water-cooled continuous argon-ion laser (ENTC-653) with a total output of 4 W and a UV output of 80 mW. The laser beam was coupled to a fibre optic that led to a single path epi photolysis head, which was incorporated into an Olympus BX51W1 fixed stage microscope. The 40 × water immersion objective (NA 0.8) of the microscope was used both for viewing the tissue and for transmitting and focusing the UV beam to the tissue for photostimulation. The UV power at the specimen was ∼5 mW, when the laser was set to an output level of 60 mW. The epi photolysis head has a motorized X–Y positioning plate for positioning the fibre optic input within the microscope field of the 40 × objective. However, since the mapping experiments required scanning over larger distances, scanning was done by mounting the microscope on an X–Y motorized stage with a range of 50 mm (Scientifica, UK), while the tissue was mounted independently on a fixed platform. The stimulus site is changed by moving the entire microscope, so the laser beam is always centred within the microscope objective and the microscope field, and the optical properties of the stimulus are identical for all stimulus sites. Stage movement was controlled by custom software written in LabView 7.1 (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA).

In the mapping of synaptic inputs with LSPS, photostimulus-induced uncaging of glutamate is used to produce depolarizing responses in neurons that are presynaptic to the recorded neuron. The depolarization in the presynaptic neuron must be large enough to trigger an AP, so that the AP can propagate to the presynaptic neuron's axon terminals and evoke synaptic transmission. The high spatial resolution of the method depends on the fact that the stimulus is only capable of evoking APs in neurons whose somata are close to the stimulus site. In order to maximize the spatial resolution of the mapping, it is desirable to use a stimulus intensity that is just sufficient to evoke one or a few APs when applied to the soma (typically the most sensitive site) of potential presynaptic neurons. A more powerful stimulus that releases more glutamate will decrease the spatial resolution of the mapping by activating neurons whose somata are at greater distances from the stimulus, either as a result of diffusing to somata at greater distances or producing suprathreshold activation at more distal dendritic sites. However, a stimulus that is too weak and fails to evoke APs in some potential presynaptic neurons will result an overly sparse picture of synaptic inputs, and some classes of presynaptic neurons that are relatively less excitable or less sensitive to the glutamate may be missed entirely. The choice of stimulus intensity thus represents a trade-off between spatial resolution and sensitivity in the mapping results.

The experimentally controllable parameters that affect stimulus strength are laser intensity, flash duration, and caged glutamate concentration. It was decided to set the laser intensity to the maximum output of the laser, because this would allow use of the lowest possible settings for the other two parameters. This is desirable because lower glutamate concentration is cost-effective, and shorter flash duration may allow greater temporal resolution for distinguishing direct from synaptic responses (see Results). At the maximum laser intensity, the UV power at the specimen (∼5 mW) was comparable to that used in previous LSPS studies. In preliminary experiments, it was found that this laser intensity could produce excessively large numbers (> 15) of APs in dorsal horn neurons when used in combination with caged glutamate concentrations and flash durations that were in the typical range used in previous LSPS studies. This indicates that the spinal dorsal horn is highly amenable to photostimulation. To produce a photostimulus that evoked no more than a few APs in most dorsal horn neurons, the latter two parameters were reduced to values of 100 μm and 3 ms, which are relatively low compared with typical values used in many LSPS studies (e.g. Pettit et al. 1999; Dantzker & Callaway, 2000). These parameters were then used in all mapping experiments (including those with caged GABA and glycine). With any further reduction, particularly in flash duration, the stimulus evoked only a subthreshold depolarization in some neurons.

In mapping experiments, photostimulation was delivered at 0.8 Hz. Mapping of photostimulation-evoked responses was done in grids with 25 μm spacing between stimulation sites. This relatively small interstimulus interval (as compared to 50 μm in most LSPS studies) was used to maximize sensitivity in the detection of synaptic inputs. Although some neurons with large dendritic trees (e.g. islet cells in lamina II) could be activated to threshold from dendritic sites at distances of 100 μm or more from their soma, many neurons could only be activated by stimuli within 25 μm of the soma, and some neurons were only activated by stimulation of the soma itself (see Results). Thus, increasing the interstimulus interval to greater than 25 μm would inevitably result in skipping over some neurons with the stimulus, and so would decrease the detection of synaptic inputs.

The stimulation grid had dorsoventral × rostrocaudal dimensions of either 475 μm × 975 μm (800 sites) for AP maps or 475 μm × 1175 μm (960 sites) for maps of synaptic responses (Fig. 1A). The smaller stimulation grid was sufficient for mapping of AP responses because APs could only be evoked from sites directly overlying the soma or dendrites of the recorded neuron. Mapping of direct responses to GABA and glycine uncaging was done with the larger stimulation grid. The sites were stimulated in a sequence generated by a non-neighbour algorithm, to avoid receptor desensitization and local depletion of the caged compound. With this algorithm, neighbouring sites are separated by 16 and 40 trials in the dorsoventral and rostrocaudal directions, respectively, when stimulating in the 475 μm × 975 μm grid.

Histology

After termination of the electrophysiological recordings, the spinal cord slice was immersed for 1 h in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4) at 4°C and then overnight in 15% sucrose in 0.1 m phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Sectioning of the slice was not performed in order to preserve the dendrites of the neurobiotin-stained neuron intact. The slice was blocked with 0.5% bovine serum albumin in 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4°C with streptavidin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (diluted 1: 500; Molecular Probes). The slice was washed in PBS, mounted on slides and viewed with a Nikon fluorescence microscope, and the images were captured with a high resolution CCD Spot camera (Diagnostic Instruments Inc.)

Data analysis

In each stimulus trial, electrophysiological data were acquired for 50 ms before and 350 ms (400 ms for AP mapping) after the photostimulus. Synaptic events as well as direct responses were detected with the aid of MiniAnalysis software (Synaptosoft, Fort Lee, NJ, USA) and confirmed by visual inspection. Peak amplitude and time of onset was determined for each event. Response amplitude for each trial (stimulation site) was measured as the sum of the peak amplitudes of all of the events whose onset occurred within the defined response time window. The response time window was 0–5 ms (relative to stimulus onset) for direct responses and 6–106 ms for synaptic responses (see Results and Figs 2 and 3). Spontaneous activity was measured in the same way, during the 50 ms pre-stimulus interval. A single value for spontaneous activity was calculated for each neuron by averaging the spontaneous activity from all of the stimulus trials for that neuron. This value for spontaneous activity was then subtracted from the response calculated for each stimulus trial.

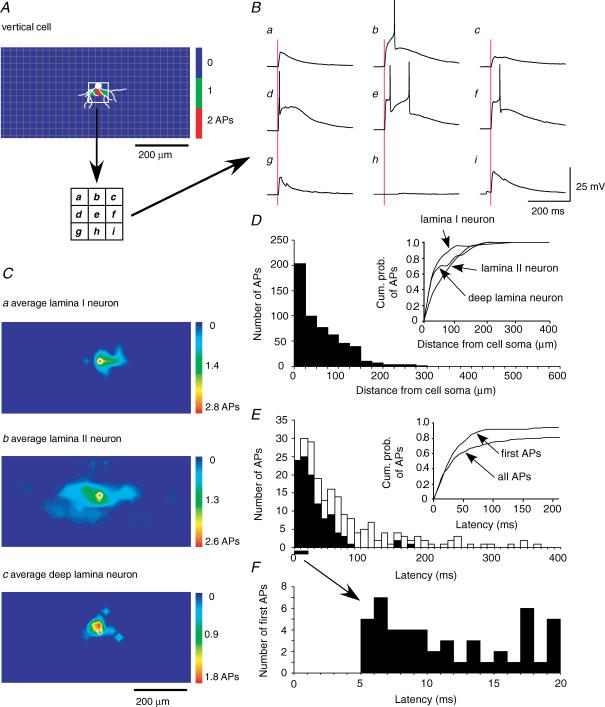

Figure 2. APs evoked by photostimulation.

A, colour-coded contour map showing the number of APs evoked in a lamina II vertical neuron by photostimulation at 25 μm intervals in the area surrounding the neuron. A drawing of the soma and dendrites is superimposed in white. AP mapping was done in an area covering 475 μm × 975 μm (dorsoventral × rostrocaudal dimensions, 800 total sites), but only the central portion of this mapping area is illustrated (350 μm × 725 μm, 450 sites). Note that the effective sites for evoking APs overlap the soma and proximal dendrites. In this and all other maps, dorsal is up and rostral is to the left. B, responses recorded from white boxed region (three × three grid) in A. One or two APs were observed in traces b, d, e and f. No response was observed in trace h, obtained from a site where no dendrite was present. Subthreshold depolarizations were observed in traces a, c, g and i, obtained from dendritic sites. Purple lines represent the time of photostimulation. C, average AP maps for lamina I (n = 3; upper), lamina II (n = 14; middle), and deeper laminae neurons (n = 9; lower). The small white circles at the centre of each map mark the soma location. D, histogram of the number of all APs (n = 26) as a function of the distance between the stimulus site and the soma (measured from the centre of the site to the centre of the site overlying the soma; thus, the first bin, 0–25 μm, includes the site overlying the soma plus the four adjoining sites). Inset shows the cumulative probability of APs as a function of distance from the soma for neurons in each lamina. E, histograms of the numbers of first APs (black bars) and all APs (white bars) (n = 11) as a function of latency (time from photostimulation onset to the peak of the AP). Inset shows cumulative probability of first and all APs. F, histogram from E shown on an expanded time scale.

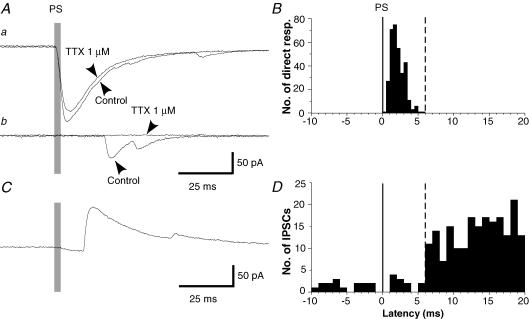

Figure 3. Determination of latency criterion for distinguishing direct from synaptic responses.

A, effect of TTX on a short-latency (a) and a long-latency (b) excitatory response evoked in one neuron from two different sites. TTX blocked the long-latency but not the short-latency response. Holding potential, −70 mV. B, histogram of the latency of TTX-resistant excitatory responses (n = 328 responses from 8 neurons). Spontaneous events were excluded by counting only those events that were present (at the same latency) both before and after the addition of TTX. C, photostimulation-evoked IPSCs. Holding potential, 0 mV. D, histogram of IPSC latencies (n = 354 responses from 5 neurons that had relatively low spontaneous activity). Inhibitory events, which can only be evoked synaptically, have latencies greater than 6 ms, while direct (TTX-resistant) responses have latencies less than 6 ms.

Averaging individual maps

Prior to combining individual maps for averaging, response amplitudes for each neuron were normalized relative to the mean amplitude of the spontaneous events recorded in that neuron, as a way to normalize for differences in series resistance between recording sessions (Dantzker & Callaway, 2000). Each response was divided by a normalization factor that was equal to the mean spontaneous event amplitude in that neuron divided by the mean spontaneous event amplitude in all of the neurons (11.5 pA). Note that this is not a normalization for differences in the number of inputs that each neuron received, but only for differences in the conditions of the micropipette recording.

Combining of individual maps for averaging requires choosing a landmark for alignment of the individual maps. Maps of AP responses and direct responses were aligned by soma location, as measured from the centre of the soma. Maps of synaptic responses were aligned rostrocaudally by soma location, and dorsoventrally by the borders of lamina II. Since there is some variation between slices in the dorsoventral width of lamina II, individual synaptic maps were normalized to make lamina II a standard width.

Results

In the spinal cord slice preparation (Fig. 1A), laminae I and II were first identified under IR-DIC by the reticulated appearance of lamina I at high magnification (Chery et al. 2000) and the translucent-band-like appearance of lamina II at low magnification. Stable recordings were obtained from 76 dorsal horn neurons for up to 2 h (lamina 1, n = 3; lamina II, n = 64; lamina III–V, n = 9). Only neurons with a resting membrane potential negative to −55 mV were included in the study. Figure 1B shows an example of a recorded lamina II islet cell injected with Alexa Fluor 488 in an unfixed slice and Fig. 1C shows the same neuron after staining for neurobiotin in a fixed slice.

Spatial and temporal resolution of photostimulation

Experiments were carried out to measure the spatial resolution of the synaptic mapping method with our photostimulus parameters in the spinal dorsal horn. Since the evoking of synaptic responses by photostimulation requires the firing of APs in presynaptic neurons, the spatial resolution of the synaptic mapping is determined by the size of the area surrounding the stimulus from which neurons can be activated to threshold. This can be revealed by recording from single neurons in current-clamp mode while mapping the locations of stimulus sites that are effective for evoking APs. Such AP maps must be obtained from a representative sample of the cell types in the dorsal horn that may be directly activated during the mapping of synaptic inputs to islet cells.

Figure 2A is an example of such an AP contour map that shows the number of APs evoked in a lamina II vertical neuron by stimulating in the surrounding area at 25 μm intervals (800 sites total in a grid of 475 μm × 975 μm dorsoventral × rostrocaudal dimensions; only the central portion of this mapping area is shown in Fig. 2A and C). Responses were recorded for 400 ms following each stimulus. No spontaneous APs were observed in this or any other neuron.

APs could be evoked from a restricted area near the soma (Fig. 2Bb, d, e and f), but not from sites away from the soma and dendrites (Fig. 2Bh and the rest of the scanning area). Since dorsal horn neurons vary in their morphological features and membrane properties (Grudt & Perl, 2002; Ruscheweyh & Sandkühler, 2002), AP contour maps were obtained for a sample of neurons in different laminae of the dorsal horn (lamina I, n = 3; lamina II, n = 14; deep dorsal horn, n = 9). The average maps are shown in Fig. 2C. In each average map, the stimulus site that evoked the largest numbers of APs was at the soma, and the number of APs decreased with increasing distance from the soma. The effective stimulus area for lamina II neurons was larger, especially in the rostrocaudal direction, than for lamina I and deep laminae neurons. The maps for both lamina I and lamina II neurons had a rostrocaudal orientation that is consistent with the predominant orientation of the neuropil in the superficial dorsal horn. This would result in a spatial resolution for synaptic mapping that is somewhat better in the dorsoventral than the rostrocaudal direction. However, none of the maps had effective sites for evoking APs that were at substantial distances from the soma (> 200 μm), and in the individual maps there were no effective sites found that were not overlying the soma or dendrites. These observations provide evidence that APs could only be evoked by direct stimulation of the soma or proximal dendrites of the recorded neuron, and could not be evoked either by excitatory synaptic inputs from stimulation of local presynaptic neurons or by back-propagation following stimulation of the recorded neuron's axon terminals.

Figure 2D shows a histogram of the number of total photostimulation-evoked APs from all laminae (n = 26) as a function of distance from the soma. The number of APs gradually decreased with increasing distance from the soma, and then sharply decreased at a distance of 160 μm. Cumulative probabilities of all photostimulation-evoked APs for neurons in each laminar region are plotted in the inset of Fig. 2D. Approximately 80% and 90% of all APs appeared within 100 and 150 μm, respectively.

Figure 2E shows histograms of the latencies (measured at AP peak) for all evoked APs (white bars) as well as for those APs that were the first in each stimulus trial (black bars) (n = 214 APs in 11 neurons). Cumulative probability plots (inset of Fig. 2E) show that 95% of first APs and 80% of all APs appeared within 100 ms. The histogram of first photostimulation-evoked APs in Fig. 2F demonstrates that no AP appeared at a latency shorter than 5 ms. This represents the minimum rise time required for the photostimulation-evoked depolarization to reach threshold, with our stimulus parameters. It would be expected that photostimulation-evoked synaptic responses would not be observed at shorter latencies than this. As described below, the minimum latency for synaptic responses was in fact found to be slightly longer (6 ms), consistent with the small additional time required for axonal propagation and synaptic delay.

It can be seen in the traces in Fig. 2B that the variation in AP latency is accounted for by variation in the time it takes the depolarization to reach firing threshold, rather than variation in the onset of the depolarization, which always has a very short latency. There was no consistent relationship between AP latency and distance of the stimulation site from the soma.

Criteria for separating direct responses and synaptic responses

As noted above, APs, which are recorded under current clamp, can only be evoked by direct (non-synaptic) stimulation of the recorded neuron. However, when recording under voltage clamp for the mapping of synaptic inputs, excitatory responses (inward currents) to photostimulation can result from either direct stimulation of the recorded neuron or from stimulation of excitatory interneurons that are presynaptic to the recorded neuron. Therefore, for mapping of excitatory synaptic responses to photostimulation, it is necessary to have a criterion to distinguish direct from synaptic responses, so that the direct responses can be excluded from the synaptic map. The simplest criterion would be a difference in response latency. In order to determine whether direct versus synaptic responses can be unambiguously distinguished based on latency, and to identify an appropriate latency criterion for making this distinction, mapping of excitatory responses was done before and after the addition of TTX to the bathing solution. Since synaptic responses depend on propagation of APs from the soma to the axon terminals of the presynaptic neuron, they should be TTX sensitive, whereas direct responses should be TTX resistant.

Figure 3A shows examples of photostimulation-evoked excitatory responses recorded under voltage clamp from two different stimulation sites before and after the addition of TTX. The longer latency response (Fig. 3Ab) was blocked by TTX whereas the shorter latency response (Fig. 3Aa) was not. Figure 3B shows a histogram of the latencies of responses that were TTX resistant and therefore were the result of direct stimulation of the recorded neuron (n = 250 responses from 7 lamina II neurons). Spontaneous EPSCs were excluded from this histogram by counting only those responses that were present at the same latency both before and after the addition of TTX. All direct responses had latencies shorter than 6 ms, and almost all (248/250, 99.5%) were less than 5 ms.

In contrast to excitatory responses, inhibitory responses (outward currents) to glutamate uncaging are always synaptic, since the only direct action of glutamate is excitatory. Figure 3C shows an example of a photostimulation-evoked IPSC, and Fig. 3D shows a histogram of IPSC latencies from a sample of five neurons. The histogram shows an abrupt increase in activity above the background level starting at a latency of 6 ms, showing that this is the minimum latency for synaptically evoked responses to photostimulation, using our stimulus parameters. This matches well with our finding of 5 ms as the earliest latency for photostimulation-evoked APs.

Comparison of the two histograms in Fig. 3 shows that there is no overlap in the two distributions. This was a critical finding. Latency therefore provides a robust and unambiguous criterion for separating direct from synaptic responses. Based on these histograms, as well as the histograms of AP latencies in Fig. 2, response time windows of 0–5 ms and 6–106 ms were chosen for quantifying direct and synaptic responses, respectively. It was important that the start of the synaptic response time window be early enough to include the first synaptic responses, because these tend to have the largest amplitude (e.g. Figs 3Ab and 4). The end of the synaptic response time window was late enough to include a high percentage of the photostimulation-evoked APs (Fig. 2E). Extending the window further would include additional spontaneous activity while giving only a small number of additional stimulus-evoked responses, and so would result in a lower response/background ratio and decreased sensitivity in the synaptic mapping.

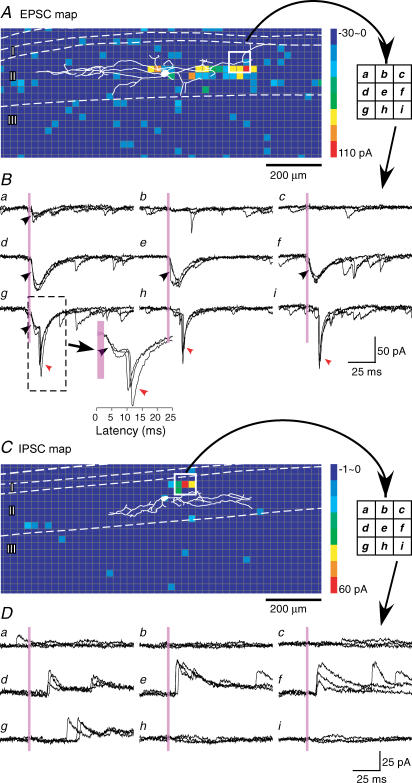

Figure 4. Construction of synaptic maps.

A, colour-coded contour map of photostimulation sites that evoked EPSCs in a single islet cell, averaged from three scans. The colours shows the response amplitude at each site, calculated as the sum of the peak amplitudes of responses whose latency to onset occurred within a time window of 6–106 ms after stimulus onset. B, responses (three trials each) recorded from white boxed region (three × three grid) in A. Only spontaneous EPSCs were seen in traces b and c. Direct responses were seen in traces a, d, e, f and g (black arrowheads). Photostimulation-evoked EPSCs were seen in traces g, h and i (red arrowheads). Traces in g were mixed responses consisting of both direct responses and EPSCs. Note that the EPSCs could be clearly separated by their latencies from the direct responses (see inset of g), and direct responses did not contaminate the synaptic map. C, map of photostimulation sites that evoked IPSCs for a single islet cell, averaged from three scans. D, responses (three trials each) recorded from white boxed region (three × three grid) in C. Photostimulation-evoked IPSCs were seen in traces d, e, f and g. Note that the short-latency (< 6 ms) direct responses that were observed in recordings of excitatory responses were not observed when inhibitory responses were recorded. White dashed lines indicate the laminar borders.

Constructing maps of photostimulation-evoked EPSCs and IPSCs

Figure 4A shows an example of a map of the amplitude of photostimulation-evoked EPSCs obtained from an islet cell, with a superimposed drawing of the soma–dendritic morphology. Scanning was performed three times. Each square shows the colour-coded response amplitude at that site, calculated by summing the peak amplitudes of all of the EPSCs occurring in the time window of 6–106 ms, and averaging over the three scans. Note that this time window excludes the direct responses, based on the latency criteria described above. The ability to distinguish direct from synaptic responses is demonstrated by the traces in Fig. 4B, obtained from stimulation in the white boxed region in A. Large direct responses were evoked from sites that contain dendrites in the middle row of the box (Fig. 4Bd, e and f), but the map nonetheless shows little or no synaptic response evoked from these sites. However, large synaptic responses were evoked from the immediately adjacent sites in the lower row (Fig. 4Bg, h and i), indicating the presence at these sites of excitatory neuron(s) that are presynaptic to the recorded islet cell. Both a direct and a synaptic response were evoked in the trace in Fig. 4Bg, but they can be distinguished by their latencies.

Figure 4C and D shows an example of a map and corresponding traces of photostimulation-evoked IPSCs from another islet cell. IPSCs could be observed in Fig. 4Dd, e, f and g, corresponding to positive sites in the boxed region in Fig. 4C.

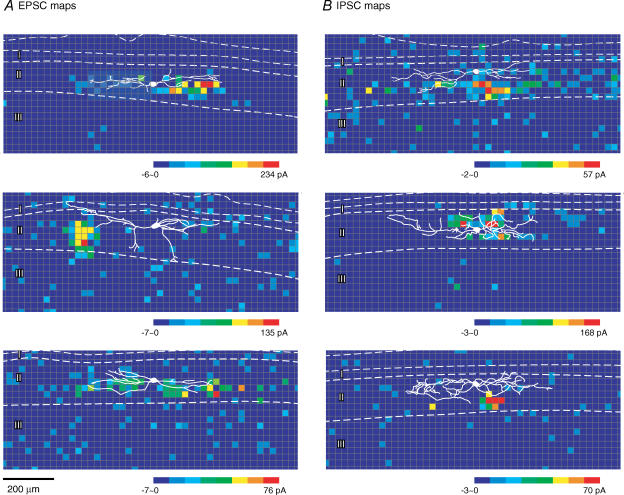

Figure 5A and B shows examples of maps of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic responses, respectively, obtained from islet cells. For all islet cells in the study, the zones that gave rise to clear presynaptic inputs, as defined by a clustering of multiple positive sites, were almost entirely contained within lamina II itself. In some cases these clusters extended to the lamina II–III border region (e.g. Fig. 5A, middle map), but never extended further ventrally beyond this border region into lamina III. Laminae I and III contained only single isolated sites but never contained clusters of multiple positive sites indicative of a clear input zone.

Figure 5.

A and B, three representative examples of photostimulation-evoked EPSC and IPSC maps.

There was no consistent difference between the inhibitory and excitatory maps in the shape of the input zones. Both exhibited a variety of shapes, including some that exhibited a pronounced rostrocaudally elongated shape and others that were more ovoid. However, there was a difference in the distribution of the input zones in the inhibitory and excitatory maps, in regard to their rostrocaudal position relative to the soma of the recorded neuron: the strongest zone of input in the excitatory maps tended to be at more distal locations relative to the soma, adjacent to dendritic sites, rather than in the perisomatic area, whereas the strongest part of the inhibitory input zones tended to be rostrocaudally restricted to more proximal positions, adjacent to the soma and proximal dendrites (discussed further below with Fig. 7A). This restriction in the distribution of the inhibitory input zones was only along the rostrocaudal axis, not the dorsoventral axis. The inhibitory zones did not tend to overlie the soma itself, but rather were displaced either dorsally or ventrally from the soma. The dorsoventral spread of the inhibitory input zones in fact tended to be somewhat greater than that of the excitatory input zones.

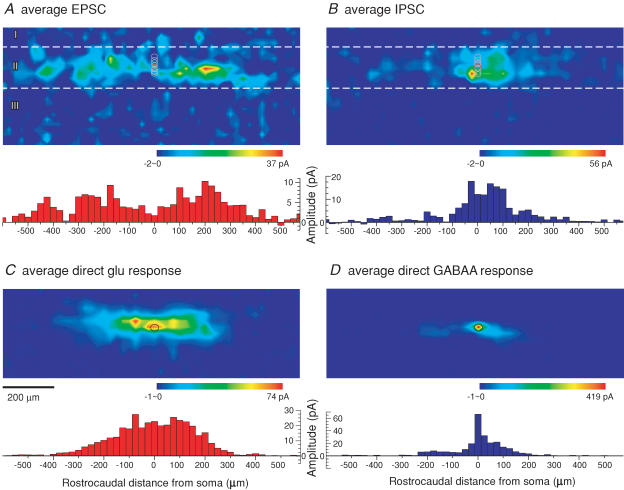

Figure 7. Averaged excitatory and inhibitory response maps.

A and B, averaged EPSC (n = 10) and IPSC (n = 8) maps (upper) and plots of mean amplitudes for sites in lamina II as a function of the rostrocaudal distance from the soma (lower). Maps from individual neurons were aligned horizontally by soma location and vertically by the borders of lamina II (white dashed lines). The red and grey ovals indicate the averaged and individual locations of the somas, respectively. C and D, averaged direct excitatory (n = 10) and GABAergic response (n = 7) maps (upper), and plots of mean amplitudes as a function of the rostrocaudal position relative to the soma (lower). The plot includes sites between 150 μm dorsal and ventral to the soma. Maps from individual neurons were aligned by soma location (black ovals).

Constructing maps of photostimulation-evoked excitatory and inhibitory direct responses

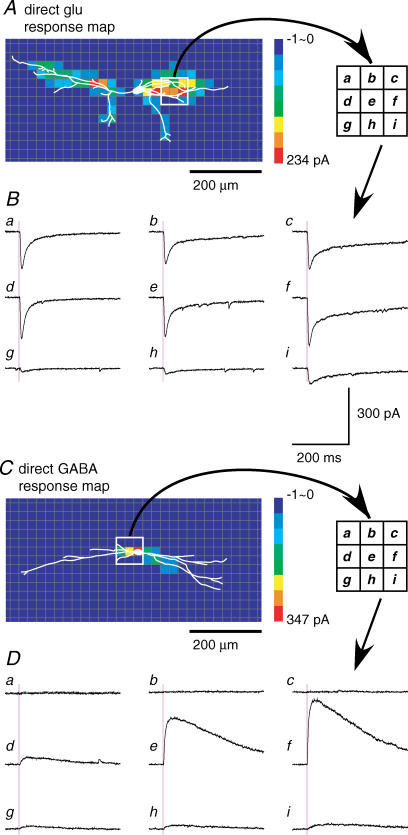

The synaptic maps in Figs 4 and 5 show the distribution of presynaptic neurons that give excitatory and inhibitory inputs to islet cells. These maps raise the question of whether there are differences in the postsynaptic distribution of inhibitory and excitatory contacts on islet cells, and whether these differences in any way parallel those found for the presynaptic neurons. One indirect approach to this question is to examine the distribution of functional neurotransmitter receptors on the islet cells by using photostimulation to map the sites that produce direct responses to uncaging of excitatory and inhibitory transmitters (such evidence is necessarily indirect because transmitter receptors may also be present at extra-synaptic sites). For this purpose, we constructed maps of direct responses to uncaging of glutamate, from the same recordings used to construct the excitatory synaptic maps described above, and we obtained additional recordings from islet cells to map the distribution of direct responses to uncaging of caged GABA and glycine. (As explained above, direct responses to glutamate uncaging were distinguished from synaptic responses based on latency. No such differentiation was necessary for the inhibitory transmitters because they can only evoke direct responses.)

Figure 6A and B shows an example of a map and traces of direct responses of an islet cell to glutamate uncaging. The largest responses were produced by stimulation of sites on the proximal dendritic tree rather than the soma. This tendency was frequently observed in other islet cells (8/10; 164 ± 25.4 pA mean maximum response in these 8 cells). In seven of these eight cells, the largest responses were observed from stimulus sites that were 50–150 μm from the soma as measured along the rostrocaudal axis, and in one cell the most effective site was 200 μm from the soma (147 pA). In all cells, stimulation at the soma also evoked relatively large direct responses (83.3 ± 12.0 pA, n = 10). Responses evoked by stimulation at increasing distances from the soma showed only moderate slowing in time course (Supplemental Fig. 1, for sites 0–178 μm from the soma), indicating that electronic attenuation in islet cell dendrites over these distances is relatively modest.

Figure 6. Direct responses evoked by photostimulation.

A, an excitatory (glutamatergic) direct response map from an islet cell. Note that the effective sites were concentrated on the dendrites, and not the soma. B, responses recorded from the white boxed region (three × three grid) in A. Largest amplitude responses (a–c, d–f) were evoked from sites with the greatest density of dendrites. C, a GABAergic direct response map from another islet cell. Effective sites are restricted to the soma and proximal dendrites. D, responses recorded from the white boxed region (three × three grid) in C. Holding potential, 0 mV. Response amplitude was largest at the soma (f), and steeply decreased along the dendrites with increasing distance from the soma (e and d). Null or only small responses were evoked in top (a–c) and bottom (g–i) rows, at sites with little or no dendritic overlap.

Figure 6C and D shows an example of a map and traces of direct responses of a different islet cell to uncaging of GABA. The distribution of positive sites was strikingly different than that found for glutamate uncaging. The largest response was evoked from the soma, and the response amplitude at dendritic sites decreased sharply with increasing distance from the soma. The maximum response amplitude was found at the soma for all of the islet cells tested (7/7). The more restricted distribution of effective sites found with GABA as compared with glutamate was not a result of a less effective stimulus, because the maximum response amplitudes for GABA (426 ± 101 pA, n = 7) were considerably larger than for glutamate. Results obtained from uncaging of glycine were similar to those for GABA (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Figure 7A–D shows average maps produced by combining the individual islet cell maps for EPSCs (n = 10), IPSCs (n = 8), direct glutamate responses (n = 10), and direct GABA responses (n = 7). (Average map and corresponding plots for glycine responses are similar to those for GABA, and are shown in Supplemental Figs 2C and D). Below each of the four average maps is a corresponding plot of the mean response amplitude versus rostrocaudal position relative to the soma (also see plots in Fig. 8A and B, in which the data from the rostral and caudal directions are combined and plotted as a single value of rostrocaudal distance from the soma). The average maps confirm the tendencies observed in the individual maps. Synaptic inputs to islet cells originated almost entirely from within lamina II. The sites giving rise to excitatory synaptic inputs showed a much more widespread rostrocaudal distribution relative to the position of the soma than those giving rise to inhibitory inputs. Inhibitory sites were largely restricted along the rostrocaudal axis to positions close to that of the soma (< 100 μm), whereas excitatory sites had their maximal distribution at rostrocaudal positions that were displaced some distance from that of the soma.

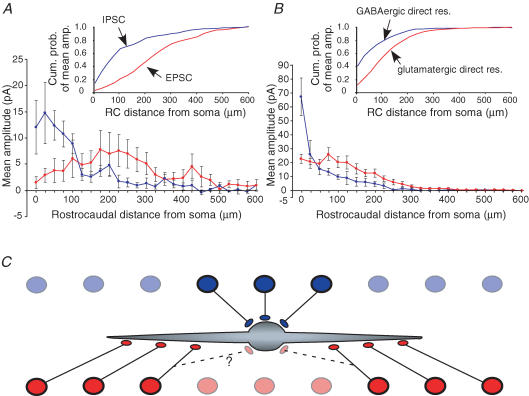

Figure 8. Distance from soma of excitatory vs. inhibitory inputs, and proposed wiring pattern.

A and B, plots of mean response amplitude versus rostrocaudal distance from the soma, for the synaptic (A) and direct (B) responses. These plots were constructed by averaging the values for the rostral and caudal directions, which were plotted separately in Fig. 7. Each graph shows data for excitatory (red) and inhibitory (blue) responses. Insets plot the cumulative probability of responses versus rostrocaudal distance from the soma. C, proposed patterns of specificity in the wiring of local inputs to lamina II islet cells. Islet cell dendrites have a predominantly rostrocaudal orientation, as viewed in the sagittal plane. Both excitatory (red circles) and inhibitory (blue circles) presynaptic interneurons are present at all positions along the rostrocaudal axis (they are shown here separated vertically for diagrammatic purposes). However, the excitatory and inhibitory interneurons at any given rostrocaudal position target separate subsets of islet cells, as determined by the rostrocaudal position of the islet cell soma relative to their own soma. Islet cells tend to receive input from inhibitory neurons, but not excitatory neurons, whose somata are at a similar rostrocaudal position to their own soma. Conversely, they tend to receive input from excitatory neurons, but not inhibitory neurons, whose somata are displaced by some distance (> 100 μm) along the rostrocaudal axis from the position of their own soma. In addition, the direct response maps suggest that the distribution of postsynaptic sites may parallel in part this differential distribution of presynaptic neurons: inhibitory transmitter receptor sites tend to be distributed relatively close to the soma, as compared with the more widespread distribution of excitatory sites on both the soma and dendrites.

The direct response maps (Fig. 7C and D) show that the excitatory and inhibitory transmitter receptor sites on the islet cells exhibited a difference in their distribution that paralleled in part the differential distribution found for the presynaptic sites. The inhibitory transmitter receptor sites showed a much more restricted distribution that was maximal at the soma and immediately dropped off very steeply at dendritic sites with increasing distance from the soma, whereas the excitatory transmitter receptor sites had a flatter, more widespread distribution that extended for some distance along the dendrites. The rostrocaudal plot of the excitatory transmitter receptor distribution had roughly the shape of a plateau centred on the soma and extending essentially without decrement for ∼125–150 μm in both directions, on which were superimposed three small peaks, at the position of the soma and at approximately 75 μm on either side. The distributions of the excitatory receptor and presynaptic sites had the common feature of being more widespread than their inhibitory counterparts, but they differed in that the excitatory receptor distribution did not exhibit a decrease at the soma.

For statistical comparison of the distributions, the position of the maxima relative to the soma was determined from the plot of response amplitude versus rostrocaudal position for each neuron (i.e. the individual plots that were combined to make the average plots shown below each map in Fig. 7). For each neuron, separate maxima were determined for the rostral and caudal directions. For the excitatory synaptic inputs, the median position of the maxima was 187 μm (75–387.5 μm, 25–75% quartiles) from the soma in the rostral direction and 212.5 μm (162.5–275 μm) in the caudal direction. For the inhibitory synaptic inputs, the median position of the maxima was 25 μm (0–75 μm) from the soma in the rostral direction and 62.5 μm (37.5–100 μm) in the caudal direction. The maxima were significantly farther from the soma for the excitatory versus the inhibitory synaptic inputs (P = 0.014 and 0.0043 for the rostral and caudal directions, respectively, Wilcoxon test on differences). For the excitatory direct inputs, the median position of the maxima was 62.5 μm (25–75 μm, 25–75% quartiles) from the soma in the rostral direction and 75 μm (0–125 μm) in the caudal direction. For the inhibitory direct inputs, the maximum was at the soma for all neurons. The maxima were significantly farther from the soma for the excitatory versus the inhibitory direct inputs (P = 0.0063 and 0.0168 for the rostral and caudal directions, respectively).

One caveat concerning these differences in distributions is that the inhibitory responses were recorded at a different holding potential than the excitatory responses (0 mV versus −70 mV). The more positive holding potential is routinely used to maximize the amplitude of inhibitory responses, but it is possible that it might also have an effect on the ability to detect more distal dendritic responses (see Discussion). Therefore, additional experiments were done to map direct responses to GABA using the same holding potential that was used for recording excitatory responses. GABA responses are normally neglibile at this holding potential, because it is approximately equal to the normal chloride equilibrium potential. Therefore, a high chloride concentration was used for the pipette internal solution in order to make the chloride equilibrium potential more positive and thus make the GABA response appear as a large inward current. To further mimic the recording conditions of the glutamate mapping, caesium was omitted from the pipette internal solution. The GABA direct responses recorded under these conditions showed the same highly restricted distribution of responsive sites. GABA produced very large inward currents at the soma (up to 1000 pA), but no response in most neurons at dendritic sites greater than 25 μm from the soma (not illustrated). The mean response decreased by 82% at 25 μm from the soma, and 93% at 50 μm from the soma, relative to the mean response at the soma (n = 3 islet cells). This decrement was actually somewhat steeper than in the original sample, probably due to the omission of caesium (Spruston et al. 1993).

Discussion

The present study used LSPS in the spinal dorsal horn to examine the spatial organization of synaptic inputs to islet cells, the major known class of inhibitory interneuron in lamina II. A novel feature of the experimental design was the mapping of both the sites of origin of synaptic inputs to the islet cells, as well as the neurotransmitter receptor sites on the islet cell membrane. The results demonstrate that local dorsal horn inputs to islet cells arise almost entirely from within lamina II, and that these local inputs include both excitatory and inhibitory components. Furthermore, we found that sites that give rise to excitatory versus inhibitory inputs exhibited a marked differential distribution: inhibitory sites tended to be located more proximal, relative to the islet cell soma, than excitatory sites, as measured along the rostrocaudal axis. This differential distribution was parallelled in part by a differential distribution of potential excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic sites, as revealed by maps of direct responses to excitatory (glutamate) and inhibitory (GABA and glycine) transmitters.

Methodological considerations

Two points that are fundamental to the LSPS method are that the photostimulation does not activate axons of passage or axon terminals, and that only monosynaptic connections are revealed by the mapping. Both of these conclusions have been confirmed in all studies that have used the technique, including ours. They are both based on the observation that action potentials can only be evoked when photostimulating sites that directly overly the soma or dendrites of the recorded neuron. In order for polysynaptic activation to occur, neurons would have to fire in response to photostimulation of their synaptic inputs, and this is not observed. A further methodological point that was critical to the validity of our results was that it was possible to establish an unambiguous criterion for separating direct and synaptic responses by latency. Complete separation was possible because there was no overlap in the latencies of these two types of response.

The individual synaptic maps typically showed one or two input zones for each neuron. Each one of these input zones is likely to represent input from one, or at most a small number of presynaptic neurons. One limitation in detecting connectivity with this technique is that only connections that are made within the plane of the slice can be detected in any one experiment, and furthermore the photostimulus has limited penetration into the depth of the slice. In addition, the detection is based on the amplitude of the evoked synaptic currents, so presynaptic neurons that generate smaller inputs are less likely to be detected. Independent of these technical considerations, a relatively sparse degree of connectivity may be a characteristic feature of the superficial dorsal horn. In studies with paired recordings, Lu & Perl (2003, 2005) found a relatively low rate of connectivity (11%) between neighbouring neurons in this region. In comparison, a study of interneurons in layer 4 of somatosensory cortex found connectivity with ∼50% of neighbouring neurons (Gabernet et al. 2005).

GABA and glycine were found to evoke direct responses in all neurons tested. This is consistent with previous electrophysiological studies that found that all neurons tested in the superficial dorsal horn responded to both GABA and glycine (Chery & De Koninck, 1999). It is also consistent with ultrastructural evidence of co-localization of GABA and glycine receptors in superficial dorsal horn neurons (Todd et al. 1996). As discussed above, the GABA- and glycine-responsive sites had a highly restricted perisomatic distribution. A similar result was found by Pettit & Augustine (2000), for interneurons in the stratum radiatum of the hippocampus; as in the present study, GABA-responsive sites were largely restricted to the peri-somatic region while glutamate-responsive sites had a much more extensive dendritic distribution. The restricted distribution of GABA- and glycine-responsive sites found in the present study raise a question about the degree to which they reflect the distribution of inhibitory synapses on islet cell dendrites. Ultrastructural studies have found evidence of inhibitory (symmetric) synapses on the dendrites of islet cells (Todd, 1988; Spike & Todd, 1992), but there is no information available about their distribution on proximal versus distal dendritic sites, or their size or density relative to excitatory synapses. It is known that GABAergic synapses in different cell types can show substantial variation in synaptic junctional area and transmitter receptor density (Nusser et al. 1997; Kubota & Kawaguchi, 2000). Possibly the number or density of inhibitory receptors that are present at more distal dendritic sites is too low to be detected by the methods used in the present study (in contrast to excitatory dendritic receptors, which could be readily detected in all islet cells).

Absence of synaptic inputs from deep dorsal horn

The synaptic inputs to lamina II islet cells were found to arise almost entirely from within lamina II, and no inputs were found from deep dorsal horn (i.e. ventral to lamina II). Projections to lamina II neurons from deep laminae have been suggested by electrophysiological observations (Baba et al. 1998), although these were based on electrical stimulation which can activate axons of passage. One reason for suspecting the presence of such projections is the finding that a proportion (∼15–25%) of lamina II neurons receive polysynaptic input from A-beta primary afferents (Baba et al. 1999; Okamoto et al. 2001) which terminate predominantly in the deep laminae. Such lamina II neurons may be responsible for relaying A-beta input from deeper laminae to lamina I projection neurons (Torsney & MacDermott, 2006). The proportion of lamina II neurons with polysynaptic A-beta input increases following peripheral inflammation or nerve injury (Baba et al. 1999; Okamoto et al. 2001). This increase might contribute to the mechanical allodynia that often characterizes these conditions. The present results indicate that islet cells are not normally the recipient of input from deep dorsal horn. It remains to be investigated whether other classes of lamina II neurons might receive such input, and whether these input patterns are altered in animal models of pain hypersensitivity.

Differential distribution of excitatory and inhibitory inputs

The differential distribution of excitatory and inhibitory presynaptic neurons that we found for lamina II islet cells has not been previously described in studies of local circuitry in other central regions, to our knowledge. Nonetheless, it is possible that such an organization might be present in other regions, but was not revealed by previously used methods. Alternatively, it might be a feature that is only present in regions that exhibit extensive interneuronal connectivity over distances that are shorter than the expanse of a single neuron's dendritic field. In the present study, it was necessary to map the sites of origin of synaptic input from within the same lamina as the postsynaptic neuron, including the territory that contained the postsynaptic neuron's somadendritic tree, because the inputs to islet cells originated from within lamina II itself. In cerebral cortex, in contrast, laser scanning photostimulation has been used most often to map local circuitry that connects neurons in separate laminae, rather than examining synaptic inputs that arise from within the territory of the postsynaptic neuron's own dendritic field.

A number of anatomical studies have found a differential somatodendritic distribution of inhibitory and excitatory postsynaptic sites, for some types of central neurons (Cant, 1984; Wentzel et al. 1995; Kultas-Ilinsky et al. 1997; Ornung et al. 1998; Gulyas et al. 1999; Megias et al. 2001; Matyas et al. 2004; Muller et al. 2006). Such studies have found that the ratio of excitatory to inhibitory synapses tends to increase at increasingly more distal sites on the soma–dendritic tree. Our direct response maps indicate that this trend also seems to hold for islet cells. Our new finding of a parallel organization in the distribution of the presynaptic neurons suggests a way in which such a differential postsynaptic distribution might arise. The differential presynaptic distribution, shown in diagram form in Fig. 8C, suggests that distinct rules govern the wiring of local presynaptic inhibitory and excitatory neurons to islet cells. The excitatory and inhibitory interneurons at any given rostrocaudal position target separate subsets of islet cells, as determined by the rostrocaudal position of the islet cell soma relative to their own soma. Inhibitory neurons tend to connect to islet cells whose somata are at a similar rostrocaudal position to their own soma, while excitatory neurons tend to connect to islet cells whose somata are displaced by some distance (> 100 μm) along the rostrocaudal axis from the position of their own soma. A parallel organization in the distribution of postsynaptic sites would result if the wiring were governed by two sequential steps or levels of specificity: (1) for both excitatory and inhibitory presynaptic neurons, the pool of potential postsynaptic sites is restricted to those sites that are at a similar rostrocaudal position to the presynaptic neuron's own soma; and (2) from this pool of potential sites, inhibitory presynaptic neurons only make actual synapses if the site is relatively proximal on the postsynaptic neurons' soma–dendritic tree, while for excitatory neurons, the postsynaptic site can be more distal. This two-step scheme would account for the more proximally located inhibitory postsynaptic sites, as well as the more distally located excitatory postsynaptic sites. However, it would not account for the more proximally located excitatory sites, since presynaptic excitatory neurons tend to be located more distally (Fig. 8C). It should be noted that the direct response maps reveal possible postsynaptic sites of input from all sources, not just local inputs, and so the proximal excitatory sites might be targeted by other (non-local) neurons. It is also possible that they represent extra-synaptic glutamate receptors (cf. results of Pettit & Augustine (2000), in hippocampal neurons), and, in fact, ultrastructural studies have found only symmetric and no asymmetric synapses on islet cell somata (Todd, 1988; Spike & Todd, 1992). Such a two-step scheme is similar to a concept that has been developed previously to describe the origin of specificity in neocortical circuits (Stepanyants et al. 2002, 2004; Shepherd et al. 2005). According to this concept, wiring specificity can be understood as a two-step process: (1) the formation of a ‘potential synapse’, as a result of the trajectory of the presynaptic axon coming in close proximity to a potential postsynaptic structure, and (2) the conversion of a potential synapse to an actual synapse. As suggested above for islet cells, each of these two steps may contribute to wiring specificity.

In the dorsal horn, the somatotopic gradient (change of receptive field location with neuronal position) is much steeper along the mediolateral than the rostrocaudal axis. This is partly a result of the fact that the terminations of individual primary afferents, including C-fibres, tend to have a long rostrocaudal but a restricted mediolateral extent (Sugiura et al. 1986; Light, 1992; Koerber & Mirnics, 1995; Wilson et al. 1996). In addition, the pattern of dendritic arborizations, as well as the intrinsic axonal connectivity within the dorsal horn, also tend to be restricted mediolaterally, which would preserve the somatotopic organization present in the pattern of the primary afferent terminations (Light, 1992; Schneider, 1992; Strassman et al. 1994). As a result, neurons within a single sagittal plane, since they occupy a similar mediolateral position, would have similar receptive field locations, as long as the rostrocaudal separation is not too great. The rostrocaudal distance separating the peaks in the distributions of inhibitory versus excitatory presynaptic neurons (∼250 μm) is too small to expect a substantial difference in their receptive field locations. Therefore, this differential distribution would not be expected to have a marked impact on shaping the topographic organization of the islet cell's receptive field (e.g. resulting in separate inhibitory versus excitatory receptive zones). This point is illustrated by the very long rostrocaudal expanse exhibited by the central terminal territories of individual primary afferent neurons, including C-fibres, which convey input from a restricted peripheral receptive field location but can extend over rostrocaudal distances in the dorsal horn several times greater than the dendritic expanse of a single islet cell (e.g. Sugiura et al. 1986). The restricted distribution of presynaptic inhibitory neurons found in the present study could not account for the generation of surround inhibition; instead, this phenomenon could be mediated by selective targeting of local inhibitory interneurons by long-ranging small-diameter primary afferent fibres, which can exert synaptic effects on lamina II neurons extending rostrocaudally over several spinal segments (Kato et al. 2004).

Islet cells constitute the majority of GABA-containing cells in lamina II (Todd & McKenzie, 1989; Heinke et al. 2004). Since glycine, the other major inhibitory transmitter in lamina II, is only found in neurons that also contain GABA (Todd & Sullivan, 1990), islet cells appear to be the predominant inhibitory cell type in this lamina, although other inhibitory cell types exist as well (e.g. Hantman et al. 2004). As with most of the cell types in lamina II, their dendritic arbor has a sagittal orientation, but islet cells differ markedly from the other cell types in having a much larger rostrocaudal dendritic extent (Grudt & Perl, 2002). It is a notable feature of lamina II that the cell type that is by far the largest in both somatic and, especially, dendritic dimensions is an inhibitory cell type. Our results show that the input that is received by the islet cell over most of this dendritic expanse is excitatory. This extended dendritic expanse could allow the islet cell to collect excitatory input, both directly and via excitatory interneurons, from a relatively large rostrocaudal area. This would include primary afferent input from C-fibres, conveyed both directly and through excitatory interneurons (since all lamina II cell types receive direct excitatory input from small-diameter primary afferents, including C-fibres). As a result, islet cells are in a position to integrate excitatory input from a relatively large number of primary afferents and excitatory interneurons, and distribute it to other lamina II neurons with much smaller dendritic fields. The islet cell input to these neurons would thus effectively extend the area over which they can receive input, and convert this more widespread excitatory input into inhibition. The summation of a relatively large number of inputs would be expected to reduce the effect of fluctuations in individual inputs, and so might serve to produce a background level of inhibition in the islet cell's postsynaptic target neurons that could exert a stabilizing effect on nociceptive transmission.

Caveats regarding receptor density and incomplete space clamp

One caveat regarding our findings of a differential distribution of excitatory versus inhibitory transmitter receptor sites involves the issue of receptor density. The variation in response amplitude that is found in the direct response maps is presumed to be related to variation in the number of receptors activated by the stimulus. This in turn will be related to receptor density as well as membrane surface area that is exposed to the stimulus. The area of exposed membrane is expected to be greatest at the soma and to decrease at dendritic sites in relation to dendritic diameter. Estimation of relative receptor density would therefore require correction for the variation in exposed membrane surface area (e.g. Pettit & Augustine, 2000). However, these considerations do not affect our conclusions because any corrections that would be made for variation in surface area would affect equally the excitatory and inhibitory maps. Our conclusions depend only on relative distributions of excitatory versus inhibitory receptors, not absolute numbers or densities.

A second caveat concerns the attenuation of dendritically generated responses when recording from the soma. Such attenuation will tend to reduce the relative amplitude of responses generated at distal versus proximal sites, and might also make some responses entirely undetectable. This consideration potentially affects any electrophysiological study that uses somatic recording to study synaptic inputs. Conclusions from all such studies only apply to those inputs that are sufficiently proximal to be detected, and results are skewed towards more proximal inputs. Thus, the distribution of inhibitory synapses shown in our maps may be more restricted than the actual distribution, due to dendritic attenuation. However, as with the issue of surface area, our conclusions do not depend on the absolute distribution, but rather on the distribution relative to that of the excitatory responses. Thus, the question then becomes one of whether dendritic attenuation might have a differential effect on excitatory versus inhibitory responses, and whether this difference could be large enough to account for the differential distributions found in the direct response maps. To consider this question, the attenuation may be divided into two factors (Johnston & Brown, 1983). First, signals generated at a dendritic site will undergo electrotonic decay during their spread to the soma. This will affect both current-clamp and voltage-clamp recordings. Second, in voltage-clamp recordings, an additional factor (also from electronic decay) that contributes to attenuation is incomplete space clamp, or failure to maintain the holding potential at distal sites, which results in a reduction in the driving force for current flow. Whereas the first factor should affect excitatory and inhibitory responses equally, the second factor of incomplete space clamp would potentially be greater for inhibitory responses, because they were recorded at a holding potential that was much further from resting potential (0 mV versus −70 mV for recording of excitatory responses). However, this factor apparently did not contribute to the differential distribution of excitatory and inhibitory transmitter receptor sites, because similar results were obtained when the mapping of GABA direct responses was repeated under recording conditions, including holding potential, that mimicked those used for recording of excitatory responses.

In addition, electrotonic attenuation of dendritic inputs, including that due to incomplete space clamp, would not seem to be capable of producing the restricted GABA response distribution, simply because such attenuation apparently cannot produce such a steep decrement over such a short distance. Even in a theoretical limiting case where the excitatory responses suffered no such attenuation and the inhibitory responses suffered the maximum attenuation possible, this difference would still not be nearly enough to account for the differential distribution in the direct response maps. For example, it has been calculated that even the highest frequency signals, which suffer the greatest electronic attenuation, would show a decrease of only ∼35% over a distance of 100 μm, in a dendrite of 1.6 μm diameter (Spruston et al. 1993), which is somewhat thinner than islet cell dendrites (∼2–3 μm mean diameter over the proximal 100 μm; G. Kato, Y. Kawasaki, R-R. Ji & AM. Strassman, unpublished observations). In comparison, the GABA direct responses decreased by 88% (with caesium) or 97% (without caesium) at a distance of 100 μm, relative to the response at the soma. One further observation that supports the idea that dendritic attenuation is not in fact very steep in islet cell dendrites is that the time course of the direct responses showed only moderate slowing with increasing distance from the soma (cf. similar arguments in Pettit & Augustine (2000) and Lowe (2002)).

Conclusions

The use of LSPS in the spinal dorsal horn revealed organized spatial patterns in the distribution of presynaptic inputs to lamina II islet cells. A differential distribution was found for excitatory and inhibitory presynaptic neurons, as well as for the excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitter receptor sites on the islet cells. This differential wiring of excitatory and inhibitory inputs suggests a principle for the organization of local circuitry within the substantia gelatinosa.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Edward Callaway and Yumiko Yoshimura for advice on the methodology for photostimulation, Megumu Yoshimura for advice on the methodology for electrophysiology, Daniel Robichaud III for LabView programming, Anna Legedza for statistical consultation, and Geoffrey Bove and Nancy Chamberlin for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by NIH grant no. R21 NS047371 (NINDS).

Supplementary material

The online version of this paper can be accessed at:

DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.128314

http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2007.128314/DC1 and contains two supplemental figures

Slowing of time course of direct responses to glutamate uncaging evoked by photostimulation at increasing distances from the soma and

Direct glycinergic responses of islet cells evoked by photostimulation.

This material can also be found as part of the full-text HTML version available from http://www.blackwell-synergy.com

References

- Baba H, Doubell T, Woolf CJ. Peripheral inflammation facilitates Aβ fiber-mediated synaptic input to substantia gelatinosa of the adult rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1999;19:859–867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00859.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba H, Kohno T, Okamoto M, Goldstein PA, Shimoji K, Yoshimura M. Muscarinic facilitation of GABA release in substantia gelatinosa of the rat spinal dorsal horn. J Physiol. 1998;508:83–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.083br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GJ, Abdelmoumene M, Hayashi H, Dubner R. Physiology and morphology of substantia gelatinosa neurons intracellularly stained with horseradish peroxidase. J Comp Neurol. 1980;194:809–827. doi: 10.1002/cne.901940407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley GN, Gent JP. Electrophysiological properties of substantia gelatinosa neurones in a novel adult spinal slice preparation. J Neurosci Meth. 1994;53:157–162. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway EM, Katz LC. Photostimulation using caged glutamate reveals functional circuitry in living brain slices. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7661–7665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway EM, Yuste R. Stimulating neurons with light. Current Opinion Neurobiol. 2002;12:587–592. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00364-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cant NB. The fine structure of the lateral superior olivary nucleus of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1984;227:63–77. doi: 10.1002/cne.902270108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chery N, De Koninck Y. Junctional versus extrajunctional glycine and GABAA receptor-mediated IPSCs in identified lamina I neurons of the adult rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7342–7355. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07342.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chery N, Yu XH, De Koninck Y. Visualization of lamina I of the dorsal horn in live adult rat spinal cord slices. J Neurosci Meth. 2000;96:133–142. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(99)00195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalva MB, Katz LC. Rearrangements of synaptic connections in visual cortex revealed by laser photostimulation. Science. 1994;265:255–258. doi: 10.1126/science.7912852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzker JL, Callaway EM. Laminar sources of synaptic input to cortical inhibitory interneurons and pyramidal neurons. Nature Neurosci. 2000;3:701–707. doi: 10.1038/76656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert WA, III, McNaughton KK, Light AR. Morphology and axonal arborization of rat spinal inner lamina II neurons hyperpolarized by μ-opioid-selective agonists. J Comp Neurol. 2003;458:240–256. doi: 10.1002/cne.10587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabernet L, Jadhav SP, Feldman DE, Carandini M, Scanziani M. Somatosensory integration controlled by dynamic thalamocortical feed-forward inhibition. Neuron. 2005;48:315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grudt TJ, Perl ER. Correlations between neuronal morphology and electrophysiological features in the rodent superficial dorsal horn. J Physiol. 2002;540:189–207. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulyas AI, Megias M, Emri Z, Freund TF. Total number and ratio of excitatory and inhibitory synapses converging onto single interneurons of different types in the CA1 area of the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10082–10097. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-10082.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantman AW, van den Pol AN, Perl ER. Morphological and physiological features of a set of spinal substantia gelatinosa neurons defined by green fluorescent protein expression. J Neurosci. 2004;24:836–842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4221-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinke B, Ruscheweyh R, Forsthuber L, Wunderbaldinger G, Sandkuhler J. Physiological, neurochemical and morphological properties of a subgroup of GABAergic spinal lamina II neurons identified by expression of green fluorescent protein in mice. J Physiol. 2004;560:249–266. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.070540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms MC, Ozen G, Hall WC. Organization of the intermediate gray layer of the superior colliculus. I. Intrinsic vertical connections. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:1706–1715. doi: 10.1152/jn.00705.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D, Brown TH. The interpretation of voltage-clamp measurements in hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1983;50:464–486. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.50.2.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato G, Furue H, Katafuchi T, Yasaka T, Iwamoto Y, Yoshimura M. Electrophysiological mapping of the nociceptive inputs to the substantia gelatinosa in rat horizontal spinal cord slices. J Physiol. 2004;560:303–315. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato G, Yasaka T, Katafuchi T, Furue H, Mizuno M, Iwamoto Y, Yoshimura M. Direct GABAergic and glycinergic inhibition of the substantia gelatinosa from the rostral ventromedial medulla revealed by in vivo patch-clamp analysis in rats. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1787–1794. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4856-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LC, Dalva MB. Scanning laser photostimulation: a new approach for analyzing brain circuits. J Neurosci Meth. 1994;54:205–218. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G, Kandler K. Elimination and strengthening of glycinergic/GABAergic connections during tonotopic map formation. Nature. 2003;6:282–290. doi: 10.1038/nn1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerber HR, Mirnics K. Morphology of functional long-ranging primary afferent projections in the cat spinal cord. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:2336–2348. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.6.2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]