SUMMARY

Protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1) is an arginine-specific protein methyltransferase that methylates a number of proteins involved in transcription and other aspects of RNA metabolism. Its role as a transcriptional coactivator for nuclear receptors involves its ability to bind to other coactivators such as GRIP1 as well as its ability to methylate histone H4 and coactivators such as PGC-1α. Its ability to form homo-dimers or higher order homo-oligomers also is important for its methyltransferase activity. To understand the function of PRMT1 further, 19 surface residues were mutated, based on the crystal structure of PRMT1. Mutants were characterized for their ability to bind and methylate various substrates, form homo-dimers, bind GRIP1, and function as a coactivator for the androgen receptor in cooperation with GRIP1. We identified specific surface residues which are important for methylation substrate specificity and binding of substrates, for dimerization/oligomerization, and for coactivator function. This analysis also revealed functional relationships between the various activities of PRMT1. Mutants that did not dimerize well had poor methyltransferase activity and coactivator function. However, surprisingly, all dimerization mutants exhibited increased GRIP1 binding, suggesting that the essential PRMT1 coactivator function of binding to GRIP1 may require dissociation of PRMT1 dimers or oligomers. Three different mutants with altered substrate specificity had widely varying coactivator activity levels, suggesting that methylation of specific substrates is important for coactivator function. Finally, identification of several mutants that exhibited reduced coactivator function but appeared normal in all other activities tested, and finding one mutant with very little methyltransferase activity but normal coactivator function, suggested that these mutated surface residues may be involved in currently unknown protein-protein interactions that are important for coactivator function.

INTRODUCTION

Protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) are a family of arginine-specific protein methyltransferases, which catalyze the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet) to specific Arg residues of specific proteins (1-3). In mammals, eight members are currently known, and each family member has a distinct set of substrates, which may overlap partially with the substrates of one or more other family members. Most family members (including PRMT1, PRMT3, PRMT4/CARM1) are type I PRMTs, i.e. they convert substrate arginine residues to monomethylarginine and asymmetric dimethylarginine. The other family members are type II enzymes, which make monomethylarginine and symmetric dimethylarginine. Type I PRMTs share a large domain (about 310 amino acids) with highly conserved sequence and three-dimensional structure; this domain is responsible for the methyltransferase activity. In addition, several family members are known to form homo-dimers or higher order homo-oligomers, and the conserved domain is also responsible for the relevant protein-protein interactions (4-6).

The founding member of the mammalian PRMT family, PRMT1, is the predominant protein arginine methyltransferase activity in most mammalian cells (7). PRMT1 is a multifunctional protein, implicated in diverse biological processes such as DNA repair, signal transduction, protein trafficking, RNA processing and transcription (1-3,8). In accordance with its multifunctional role, it has diverse substrates involved in many different biological processes, particularly various aspects of RNA metabolism. For example, PRMT1 methylates histone H4 in connection with chromatin remodeling (9,10), coactivator PGC-1α in connection with transcriptional activation (11), and many RNA-binding proteins involved in various aspects of RNA metabolism, such as hnRNPs and poly A binding proteins (8,12-14). In comparison to other members of the PRMT family, PRMT1 seems to have the most diverse array of substrates. While a clear consensus sequence for PRMT1 substrates has not emerged, most methylation sites fall into two or three categories. Substrate Arg residues of many protein substrates are found in glycine and arginine rich (GAR) motifs which frequently occur in RGG repeats of proteins such as fibrillarin and nucleolin (2,15). Other substrate Arg residues occur in RXR sequences (11,16). However, some substrates, such as Arg 3 of histone H4 do not occur in either of the above contexts (9,10). How PRMT1 can recognize and methylate so many different protein substrates is not clear.

In addition to its enzymatic activity, protein-protein interactions also play an important role in the various functions of PRMT1. Homo-dimerization and/or homo-oligomerization of the PRMT1 subunit is important for its enzymatic activity (6). Furthermore, PRMT1, in addition to some other PRMT family members like CARM1, function as coactivators for nuclear receptors and other transcriptional activators (2). PRMT1 is recruited to promoters of specific genes through direct interactions with DNA-binding transcription factors, such as p53 and YY1 (17,18), or by binding to other coactivators, such as the p160 coactivator GRIP1 (19), which associates directly with nuclear receptors and many other types of DNA-binding transcription factors. The mechanism by which promoter-associated PRMT1 contributes to transcriptional activation appears thus far to involve methylation of histone H4 (9,10) and other coactivators, such as PGC-1α (11), in the vicinity of the promoter. Histone H4 methylation cooperates with histone H3 methylation by CARM1, histone lysine acetylation by various histone acetyltransferases, and various other post-translational histone modifications to help remodel chromatin structure to provide access to RNA polymerase II for transcriptional initiation (2,17,20,21). Thus, for substrates found in the chromatin and transcription machinery, the methyltransferase activity of PRMT1 appears to be regulated by controlling its access to histones and substrate proteins in specific chromosomal loci. Both the homo-dimerization/oligomerization and GRIP1 binding by PRMT1 and CARM1 are mediated by the methyltransferase regions of the PRMTs (6,22).

In addition to the conserved methyltransferase domain, most PRMTs contain unique N-terminal regions of varying lengths, up to 200 amino acids long (5). However, since the unique N-terminal region of PRMT1 is only about 35 amino acids in length, most of the functions of PRMT1 must be carried out by the 310-amino acid conserved region. A more detailed dissection of the various functions found in the conserved domains of PRMTs (e.g. methyltransferase activity, dimerization, and GRIP1 binding) has been difficult, since the conserved region consists of an AdoMet binding domain and a barrel-like domain which fold together to form a single functional unit (5,6,23). Thus, deletions of virtually any portion of the conserved region generally results in loss of structural integrity and partial or complete loss of all three of the above-mentioned activities. Thus, to further explore the relationships among these activities and their relevance to the transcriptional coactivator function of PRMT1, we decided to perform site-directed mutagenesis on surface residues of the conserved region of PRMT1.

The structure of PRMT1 co-crystallized with GAR peptide substrates indicated that PRMT1 has many different meandering grooves on its surface, and GAR peptides were observed binding in several of the grooves (6). These grooves may represent multiple binding sites for different substrates of PRMT1 and may explain how it can methylate Arg residues within so many different sequence contexts. Based on the structural information, scanning surface mutagenesis was performed, creating 19 non-conservative surface mutations. We report the characterization of these mutations for their effects on the methyltransferase activity with various protein substrates, homo-dimerization/oligomerization, binding interactions with substrates and GRIP1, and coactivator activity with a nuclear receptor. The results identify specific residues important for each of these functions and reveal specific relationships between different functions that provide new information about the mechanism of PRMT1 function as a methyltransferase and a coactivator.

RESULTS

Identification of surface residues important for histone H4 methylation by PRMT1.

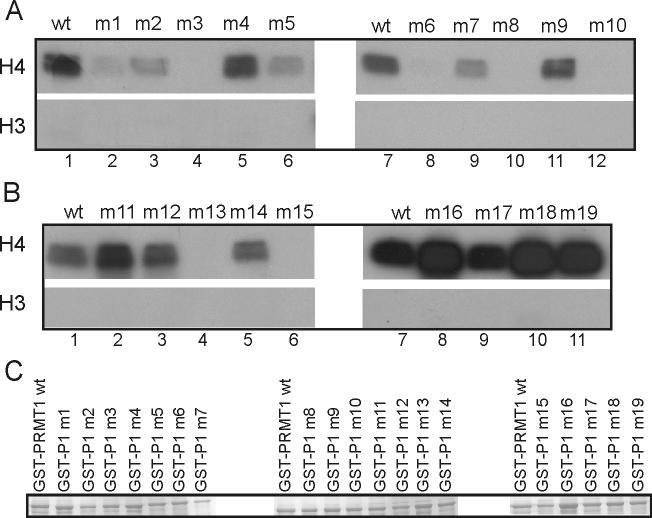

In the crystal structure of PRMT1 (6), the meandering surface grooves could represent binding sites for substrates or for other protein-interaction partners of PRMT1. Therefore, we mutated surface residues in and near these grooves. Since many substrates of PRMT1, such as histone H4 and GAR sequences, are positively charged, we focused our efforts on negatively charged Glu or Asp surface residues. To enhance the probability that each single point mutation would interfere with a protein-protein interaction, we mutated negatively charged Glu or Asp residues to positively charged Lys or Arg residues. 19 different surface mutations were generated on PRMT1 (Fig. 1), and each mutant was expressed as a GST-fusion protein. All of the GST-PRMT1 mutants were expressed at similar levels in bacteria (Fig. 2C). Each mutant PRMT1 protein was analyzed for methyltransferase activity on recombinant histone H4 by incubating with [methyl-H3]AdoMet (Fig. 2A-B). The results allowed classification of the PRMT1 mutants into three categories. PRMT1 mutants m1, m3, m6, m8, m10, m13 and m15 exhibited very little or no activity. PRMT1 mutants m2, m5 and m7 displayed partial loss of enzymatic activity but had more activity than the previously mentioned group. PRMT1 mutants m4, m9, m11, m12, m14, m16, m17, m18 and m19 maintained wild type enzymatic activity.1 Thus it appears that surface residues along at least some of the surface grooves of PRMT1 are important for the methylation of histone H4.

Fig. 1.

Locations of surface mutations on PRMT1. Upper panels show crystal structure of PRMT1 monomer viewed from opposite sides of the protein. Lower panel shows the structure of a homodimer with arrows indicating the dimer interface. Acidic regions are shown in red, while basic regions are blue. Locations of the dimerization arm, docking site for the dimerization arm, active site (where AdoMet and the substrate Arg residue bind) are also indicated. Open arrowheads indicate locations of some surface grooves and bound GAR peptides (curving green cylinders) were observed binding in some of the grooves. Sequence of the GAR peptide (called R3) is shown (15). Acidic PRMT1 surface residues that were mutated to Lys or Arg in this study are designated with abbreviations such as M1 etc, and their locations are indicated with thin black arrows. For each mutant the corresponding amino acid substitutions are given (list). Adapted from Zhang and Cheng (6).

Fig. 2.

Methyltransferase activity of PRMT1 mutants with histone H4. (A & B) Histone H4 or H3 (5 μg) was incubated with approximately 1 μg of each GST-PRMT1 mutant and [3H]AdoMet. Methylated products were observed by SDS-PAGE and autoflurography. (C) Recombinant GST-PRMT1 mutant proteins were observed by SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie Blue. Results shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

PRMT1 surface residues important for methylation of proteins in cellular extracts.

To test a broad range of substrates in a single reaction, we prepared hypomethylated cell extracts from mouse embryo fibroblast (MEF) cells grown with adenosine dialdehyde (Adox), an inhibitor of AdoMet-dependent methylation. Adox effectively inhibits AdoMet-dependent methylation in MEF cells and thus causes hypomethylation of many proteins. Endogenous methyltransferases in the cell extracts were inactivated by heat treatment. Indeed, wild type PRMT1 methylated a variety of specific proteins in the cell extracts (Fig. 3A, lanes 1−2 and 9). When cell extracts were incubated with [3H]AdoMet but without exogenous GST-PRMT1 (Fig. 3B, lane 1) or incubated without AdoMet and GST-PRMT1 (Fig. 3A, lane 8), no methylated products were observed, indicating that endogenous protein methyltransferases had been successfully inactivated. Similar tests with the PRMT1 mutants allowed us to classify them into four categories. 1) Mutants m4, m9, m11, m12, m14, m16, m17, m18 and m19 displayed wild type levels and patterns of substrate methylation in the cell extracts. This set of mutants was identical to the set which exhibited wild type activity on histone H4. This suggests that the residues altered in these mutants are unlikely to be important for enzymatic activity or substrate specificity. 2) Mutants m1, m3, m13, and m15 exhibited no or almost no detectable activity. 3) Mutants m6, m8 and m10 exhibited dramatically reduced methylation activity, but the pattern of methylated products appeared to be indistinguishable from that produced by wild type PRMT1. 4) Interestingly, m2, m5 and m7 displayed a substantial but not complete loss of activity, but the pattern of products was different from that produced by wild type PRMT1. For example, m2 displayed a more restricted pattern of substrates than wildtype (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 2 and 4). Most notably, m2 was dramatically reduced in its ability to methylate a 35 kDa protein (Star 1 in Fig. 3A), 20 kDa protein (Star 2) and 60 kDa protein (Star 3). m2, however, still maintained its ability to methylate a 70 kDa protein (Star 4) at approximately wild type levels. Mutants m5 and m7 had substantially reduced activity, compared with wild type PRMT1, but their pattern of methylated products was generally similar to the wild type pattern, except for the their reduced methylation of the 60 kDa protein (star 3). Thus, the surface residues mutated in m2, m5 and m7 help determine substrate specificity of PRMT1. None of the mutations seem to change substrate specificity of PRMT1 in a way that resulted in methylation of obviously novel substrates.

Fig. 3.

Methyltransferase activity of PRMT1 mutants with hypomethylated cell extracts. Hypomethylated mouse embryonic fibroblast extracts were incubated with 1 μg of each GST-PRMT1 mutant and [3H]AdoMet. Methylated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by fluorography. Positions of molecular weight markers are indicated on the left. Results shown are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Differential methyltransferase activity of PRMT1 on histone H4 and GST-GAR.

To explore further the apparently altered substrate specificity of some of the PRMT1 mutants, we tested for differential activity on two specific substrate proteins with different types of sequence motifs surrounding the methylation sites: histone H4 and GST-GAR. GST-GAR contains the first 148 amino acids of human fibrillarin, which contains 14 Arg residues in a glycine-rich context (24). PRMT1 methylates GST-GAR within RGG repeats and methylates histone H4 within the N-terminal sequence, SGRGK. The m4 and m9 mutants, which had displayed wild type methyltransferase activity in the previous assays, again exhibited wild type ability to methylate histone H4 and GST-GAR (Fig. 4, lanes 1, 3, and 7). PRMT1 mutants m8 and m15 (lanes 6 and 8) displayed complete loss of activity on histone H4 and almost complete loss of activity on GST-GAR. Mutants m2 and m5, which exhibited altered product patterns with cell extracts (Fig. 3), exhibited altered methylation of histone H4 vs. GST-GAR (Fig. 4, lanes 2 and 4). Mutant m2 maintained near wild type activity on GST-GAR but had dramatically reduced activity with histone H4. Mutant m5 exhibited severe loss of methylation of both substrates. Mutant m7 exhibited reduced activity with histone H4 and a more severe loss of activity with GST-GAR (compare the ratio of band densities for M7 versus wild type PRMT1). Since mutants m2, m5, and m7 also exhibited a dramatic change in substrate specificity patterns with hypomethylated cell extracts, it is likely that the surface residues mutated in m2, m5, and m7 play critical roles in regulating PRMT1 methyltransferase substrate specificity.

Fig. 4.

Differential methyltransferase activity of PRMT1 mutants with histone H4 vs. GST-GAR. Histone H4, histone H3, GST-GAR or GST (5 μg) was incubated with approximately 1 μg of each GST-PRMT1 mutant and [3H]AdoMet. Reaction products were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoflurography. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

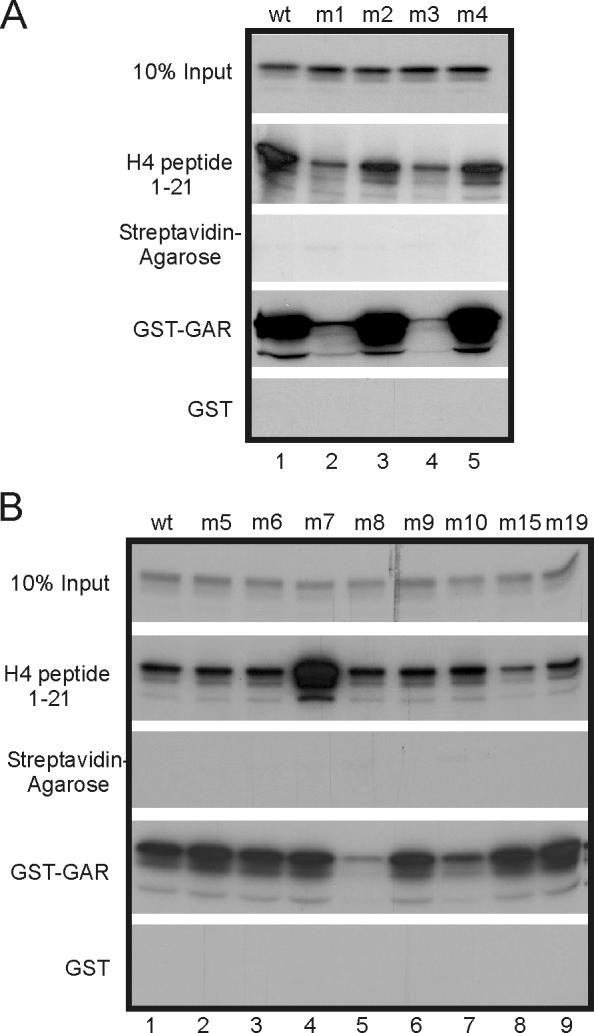

Binding of PRMT1 mutants to substrates histone H4 and GST-GAR.

One possible explanation for loss of methyltransferase activity or altered substrate specificity in specific PRMT1 mutants would be loss of the ability to bind some or all substrates. We, therefore, analyzed various mutants of PRMT1 for their ability to bind to a histone H4 N-terminal peptide or GST-GAR (Fig. 5). In vitro transcribed/translated mutants of PRMT1 were incubated with biotin-tagged histone H4 (1-21) peptide or GST-GAR fusion proteins bound to agarose beads. Bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Wild type PRMT1 and most of the mutants tested bound strongly to both histone H4 peptides and GST-GAR proteins. Interestingly, mutants m1 and m3 exhibited the most dramatic loss of binding to both histone H4 and GST-GAR proteins (Fig. 5A, assays 2 and 4). These results correlate well with the essentially complete loss of methyltransferase activity for the m1 and m3 mutants on histone H4 and hypomethylated cell extracts (Fig. 2 and 3). Furthermore, they suggest that m1 and m3 lost their methyltransferase activity because they cannot bind to their substrates. Mutant m8 exhibited normal binding to histone H4 peptide and severely reduced binding to GST-GAR, even though its methyltransferase activity was severely reduced for both of these two substrates. Mutant m15 had reduced binding to histone H4 peptide but wild type binding to GST-GAR, even though it had very little methyltransferase activity on any of the substrates we tested. Thus, the explanation for the loss of methyltransferase activity in m8 and m15 is not clear and could be complex. Mutants m2 and m5, which showed reduced methyltransferase activity for histone H4 and/or GST-GAR, appeared to bind normally to both substrates. This suggests that the m2 and m5 mutations affect methylation without affecting substrate binding; alternatively, the assay conditions used here may not be stringent enough to distinguish subtle losses of substrate binding. Interestingly, mutant m7, which had reduced methyltransferase activity with histone H4 and GST-GAR, showed a dramatic increase in binding to histone H4 and normal binding to GST-GAR (Fig. 5B, lane 4). This suggests that the decreased methyltransferase activity of m7 may be due to decreased substrate dissociation rate or altered binding of substrates, such that they are not optimally aligned for the catalytic site.

Fig. 5.

Binding of PRMT1 mutants to histone H4 and GST-GAR. In vitro synthesized, 35S-labeled PRMT1 mutants were incubated with streptavidin-agarose beads containing bound biotin-tagged histone H4 peptide, streptavidin agarose beads alone, or GST-GAR or GST bound to glutathione-agarose beads. Bound PRMT1 was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Effects of surface mutations on PRMT1 dimerization and GRIP1 binding.

In addition to substrate binding, binding of non-substrate proteins also plays important roles in PRMT1 function. The X-ray crystal structure of PRMT1 captured the protein in the form of a homodimer and showed that the dimerization arm of each monomer interacts with a corresponding docking site on the other monomer (Fig. 1) (6). Deletion of the loop that forms the dimerization arm indicated that the ability to form homodimers is important for the methyltransferase activity of PRMT1; there is also evidence that PRMT1 can form higher order oligomers (6). In addition, interaction of PRMT1 with activation domain 2 (AD2) at the C-terminal end of GRIP1 is required for the coactivator function of PRMT1, presumably because PRMT1 is recruited to promoters through its interaction with GRIP1 (19). Similarly, PRMT1 is also recruited as a coactivator by direct protein-protein interactions with DNA-binding transcription factors such as YY1 and p53 (17,18). Targeted methylation of histone H4 on promoters of specific genes by PRMT1 is thus thought to be directed by the binding of PRMT1 by these transcription factors and coactivators.

To define surface residues that are important for PRMT1 homo-dimerization and for binding to GRIP1 AD2, in vitro translated wild type or mutant PRMT1 was incubated with bead-bound GST-PRMT1 (wild type) or GST-GRIP1-AD2 in GST pull-down assays. Wild type PRMT1 bound strongly to GST-PRMT1, weakly to GST-GRIP1-AD2, and not at all to the negative control, GST alone (Fig. 6). Interestingly, in multiple experiments mutants m1, m3, m8 and m13 exhibited moderate to severe loss of binding to GST-PRMT1, while m10 and m6 showed a slight loss (Fig. 6A and B; and data not shown). Since the ability to dimerize has been previously linked to methyltransferase activity, the dimerization defects of these mutants may explain their loss of methyltransferase activity. All other mutants tested had wild type or near-wild type dimerization activity.

Fig. 6.

Homo-dimerization and binding to GST-GRIP1-AD2 by PRMT1 mutants. GST pull-down assays were performed with GST, GST-PRMT1 (wild type) or GST-GRIP1-AD2 (GRIP1 amino acids 1122−1462) and in vitro synthesized 35S-labeled PRMT1 (wild type or mutants). Bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Results shown are representative of four independent experiments.

Surprisingly, all the mutants with moderate to severe loss of dimerization activity all exhibited increased binding to GRIP1-AD2, compared with wild type PRMT1. Furthermore, among all 19 mutants, it was primarily the homo-dimerization mutants which displayed substantial and reproducible increases in binding to GRIP1-AD2, suggesting a possible relationship between these two binding activities, i.e. that homo-dimerization might inhibit binding to GRIP1 and vice-versa. To explore further the possible link between these two activities, we performed similar tests on the previously characterized PRMT1 ΔARM mutant. This mutant lacks amino acids 188−222, which form a loop or arm, conserved among several PRMT family members, that is important for forming the homo-dimer interface (5,6,23) (Fig. 1). As with our other dimerization mutants, the PRMT1 ΔARM mutant displayed greatly reduced homo-dimerization and substantially increased binding to GRIP1 AD2 (Fig. 6C).

Effects of surface mutations on transcriptional coactivator activity of PRMT1.

Because it has been shown that PRMT1 can act as a transcriptional coactivator for nuclear receptors and that its methyltransferase activity is required for its coactivator function (10,11,17,19), we then went on to test which of our surface mutations of PRMT1 had an effect on its coactivator function, and how coactivator activity of the mutants correlated with the other properties of the mutants which we have measured. CV-1 cells were transiently transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid (MMTV-LUC) controlled by the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter, along with mammalian expression vectors for AR, GRIP1 and PRMT1 (wild type or mutants). Transfected cells were then grown in 20 nM DHT, and cell extracts were tested for luciferase activity. We have shown previously that PRMT1 coactivator function depends on the presence of GRIP1, presumably since PRMT1 is recruited to the promoter of the reporter gene by its interaction with the AD2 domain of GRIP1, which is recruited by the DNA-bound, hormone-activated steroid receptor (19). GRIP1 alone enhanced the activity of the hormone-activated AR, and co-expression of wild type PRMT1 with GRIP1 further enhanced reporter gene activity (Fig. 7A, assays 1−3). Under these assay conditions, the methyltransferase activity of PRMT1 was required for coactivator function, since the PRMT1 E153Q mutant (which has no methyltransferase activity due to a mutated arginine binding pocket) failed to enhance the activity observed with GRIP1 and AR (compare assays 2, 3, & 23).

Fig. 7.

Coactivator activity of PRMT1 with GRIP1 and androgen receptor. (A) CV1 cells were transiently transfected with MMTV-LUC reporter plasmid (125 ng) and expression vectors encoding AR (10 ng) , GRIP1 (50 ng) and PRMT1 (200 ng). Transfected cells were grown in culture medium with 20 nM DHT and extracts of harvested cells were tested for luciferase activity. Results shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. (B) Expression of PRMT1 mutants was determined in COS7 cells after transfection with 2.5 μg PRMT1 mutant expression vectors. PRMT1 was detected by immunoblot with anti-HA antibody.

Most of the dimerization-deficient mutants (m3, m6, m8, m10, and m13) had reduced expression relative to wild type PRMT1 in transient transfections (Fig. 7B), although they were expressed well in bacteria (Fig. 2C) or in vitro (Fig. 6). Thus, the fact that they had little or no coactivator activity (Fig. 7A) may be partly or wholly due to their low expression. Only one member of the dimerization-deficient group, m1, was expressed at wild type levels in mammalian cells, but it still exhibited no coactivator function (Fig. 7A, assay 4). All other mutants were expressed at near-wild type levels in mammalian cells (Fig. 7B).

There were nine mutants that performed at wild type levels in all of the methylation, substrate binding, dimerization, and GRIP1 binding assays tested. Of these nine, three (m9, m11, and m12) also had wild type coactivator function (Fig. 7A). The other six mutants that had wild type activity in all other tests (m4, m14, m16, m17, m18, and m19) exhibited somewhat reduced coactivator function. This suggests that the coactivator activity of PRMT1 may involve properties in addition to those we measured. For example, the coactivator function of PRMT1 may also require protein-protein interactions with currently unknown binding partners, and these mutants may have deficiencies in those currently unknown binding interactions. Another indication that protein-protein interactions may contribute to PRMT1 coactivator function came from the phenotype of mutant m15. In spite of exhibiting almost no methyltransferase activity in our assays, mutant m15 surprisingly showed wild type coactivator function (Fig. 7A, assay 18). This suggests that PRMT1 can function as a coactivator even without its methyltransferase activity and raises the possibility that the m15 mutation not only knocked out methyltransferase activity, but also somehow enhanced the methyltransferase independent coactivator function of PRMT1. Alternatively, m15 may still have near normal methyltransferase activity for unknown proteins which are important for its coactivator function; or the mutant PRMT1 could recruit an endogenous wild type PRMT1 molecule as a homodimer partner.

The three mutants with altered methyltransferase substrate specificity (m2, m5, and m7) exhibited a wide range of coactivator activity levels, from wild type (m5) to partial (m2) to none (m7). These results seem to indicate that the coactivator function of PRMT1 requires the ability to methylate specific substrates among the full repertoire of wild type PRMT1. Furthermore, since mutants m2 and m5, which had partial and wild type coactivator function, respectively, displayed reduced histone and GST-GAR methylation ability but wild type ability to methylate some other substrates in cell extracts, methylation of non-histone proteins may be important for the coactivator function of PRMT1 observed in our assay system.

DISCUSSION

Based upon the results of the methyltransferase, substrate binding, dimerization, GRIP1 binding, and coactivator assays, we have classified the 19 surface mutants of PRMT1 into five different phenotypic groups (Table 1 and Fig. 8): 1) mutants which behaved as wild type in all assays (m9, m11, m12); 2) mutants with partial coactivator activity which behaved as wild type in all other assays (m4, m14, m16, m17, m18, m19); 3) mutants with compromised dimerization, which also had moderately to severely compromised methyltransferase activity but increased GRIP1 binding ability (m1, m3, m6, m8, m10, m13); 4) mutants with altered methyltransferase substrate specificity (m2, m5, m7); 5) one mutant with almost no methyltransferase activity but normal coactivator activity (m15).

Table 1.

Summary of PRMT1 Mutant Phenotypes

| Mutation | Methyltransferase Activity | Substrate Binding | Binding of Other Proteins | Coactivator Activity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| histone H4 | GST-GAR | cell extract | histone H4 | GST-GAR | dimerization | GRIP1 AD2 | |||

| Phenotype: wild type | |||||||||

| wt | ++++ | ++++ | wt | wt | wt | ++++ | + | wt | |

| m9 | E245R | ++++ | ++++ | wt | wt | wt | ++++ | + | wt |

| m11 | E302K | ++++ | Not tested | wt | wt * | Not tested | ++++ | + | wt |

| m12 | D303R | ++++ | Not tested | wt | wt * | Not tested | +++ * | + * | wt |

| Phenotype: partial coactivator activity | |||||||||

| m4 | E52R | ++++ | ++++ | wt | wt | wt | +++ | + | partial |

| m14 | E312R | ++++ | Not tested | wt | wt * | Not tested | ++++ * | + * | partial |

| m16 | D334R | ++++ | Not tested | wt | wt * | Not tested | ++++ | + | partial |

| m17 | D336K | ++++ | Not tested | wt | wt * | Not tested | ++++ | + | partial |

| m18 | E343K | ++++ | Not tested | wt | wt * | Not tested | ++++ * | + * | partial |

| m19 | D349R | ++++ | Not tested | wt | wt | wt | ++++ | + | partial |

| Phenotype: dimerization deficient with increased GRIP1 binding | |||||||||

| m1 | E46K | + | Not tested | none | weak | weak | ++ | +++ | none |

| m3 | D51R | none | Not tested | none | weak | weak | + | ++++ | none |

| m6 | D164K | none | ++ * | reduced | wt | wt | +++ | ++ | none |

| m8 | D238K | none | + | reduced | wt | weak | ++ | +++ | none |

| m10 | D246R | none | ++ * | reduced | wt | weak | +++ | +++ | none |

| m13 | E311K | none | Not tested | none | slight decrease * | Not tested | + | ++++ | none |

| delARM | del188−222 | inactive on hnRNP A1 | ** | Not tested | Not tested | + | ++++ | Not tested | |

| Phenotype: altered substrate specificity | |||||||||

| m2 | E47K | ++ | +++ | altered | wt | wt | ++++ | + | partial |

| m5 | E129R | + | + | altered | wt | wt | ++++ | ++ | wt |

| m7 | E236R | ++ | + | altered | increased | wt | +++ | ++ | none |

| Phenotype: almost no methyltransferase activity but normal coactivator activity | |||||||||

| m15 | D330K | + | + | none | decreased | wt | ++++ | + | wt |

| Phenotype: no methyltransferase activity due to mutant Arg binding pocket | |||||||||

| mE153Q | inactive on hnRNP A1 | ** | increased * | wt * | Not tested | Not tested | none | ||

data not shown

from (6)

Fig. 8.

PRMT1 mutations grouped by phenotype. Opposite side views of a ribbon diagram of a PRMT1 dimer are shown. The location of each class of mutation on the PRMT1 surface is indicated by a different color, as indicated at the bottom of the figure. Circles of corresponding colors are used to show localization of mutations with similar phenotypes within a specific region of the PRMT1 surface.

The phenotype of the second group, comprised of mutants m4, m14, m16, m17, m18 and m19, suggests that our current model for PRMT1 coactivator function needs to be revised. Our previous model required that PRMT1 must interact with transcription factors, such as p53 and YY1 (17,18), or with other coactivators, such as GRIP1 (19), in order to be recruited to specific promoters. Then it requires its methyltransferase activity to methylate histone H4 (9,10) as well as other coactivators, such as PGC-1α (11). However, the group of mutants comprised of m4 et al had compromised coactivator activity for AR in spite of the fact that they had normal GRIP1 binding activity and methyltransferase activity on a variety of substrates. We therefore conclude that these mutants must have a compromised ability to bind some other protein(s) that is/are important for PRMT1 coactivator function. These unknown protein interaction partners could be specific substrates that we have not identified, or proteins that are activated by their protein-protein interactions with PRMT1 and subsequently contribute to transcriptional activation. Except for m4, these mutations are all located in one general surface area of PRMT1 (Fig. 8, red circle). Thus, there appears to be one particular interaction surface that is important for interacting with one or more proteins that contribute to transcriptional activation. The identification of this/these protein partner(s) should lead to important insights into PRMT1 coactivator function and the mechanism of transcriptional activation.

The phenotype of mutant m15, which had an almost complete loss of methyltransferase activity for all substrates tested but retained normal ability to cooperate with GRIP1 as a coactivator for AR (Table 1 and Fig. 7), also suggests that interaction of PRMT1 with other protein partners is important for its coactivator function. This phenotype would also seem to suggest, on the surface, that the methyltransferase activity of PRMT1 is not required for its coactivator function. However, as discussed earlier, substantial previous evidence has shown that the methylation of histone H4 and other transcription factors by PRMT1 plays a critical role in its coactivator function. Furthermore, PRMT1 mutant E153Q, which lacks methyltransferase activity due to a mutation in the arginine binding pocket (6), exhibited no coactivator function in the same assay where m15 retained wild type coactivator function. Therefore, we conclude that the m15 mutation D330K eliminates methyltransferase activity but apparently also alters some other function (e.g. a specific protein-protein interaction) and thereby enables PRMT1 coactivator function to occur even in the absence of methyltransferase activity. For example, the D330K mutation could promote binding of a protein that contributes to transcriptional activation. It is noteworthy that the m15 mutation is very close to the surface where most of the partial coactivator mutations are found (Fig. 8, m15 is located just outside of the red circle). Thus, the m15 mutation could conceivably enhance binding of the same protein(s) that is/are inhibited from binding by the partial coactivator mutations. The m15 mutation did not affect structural integrity since it showed normal dimerization and GRIP1 AD2 binding. It also bound GST-GAR normally but had somewhat decreased binding with histone H4. Thus, PRMT1 coactivator function may involve both the methyltransferase activity of PRMT1 and the ability to bind various proteins that are presumably downstream from PRMT1 in the coactivator signaling pathway that leads to transcriptional activation. It is noteworthy that similar conclusions have been reached for the coactivator function of CARM1 (22). While we favor the above interpretation, we cannot rule out the possibility that m15 retains methyltransferase activity for unknown proteins that are important for transcriptional activation.

Mutants m2, m5 and m7 exhibited altered patterns of methyltransferase substrate specificity. Each of these mutants methylated some substrates as well as wild type PRMT1 under the conditions we used, but they exhibited reduced ability or no ability to methylate other substrates that were methylated by wild type PRMT1. Surprisingly, we did not observe any deficiency in substrate binding among these mutants. Thus, either the conditions we used were not sensitive enough to detect relatively subtle losses of substrate binding, or the mutations caused a loss of ability to catalyze the methyl transfer after the protein substrate is bound. These mutants dimerized and bound GRIP1 normally or slightly better than wild type PRMT1, suggesting no gross malformation of protein tertiary structure. Since these three mutants exhibited widely varying levels of coactivator function, we conclude that methylation of some substrates is more important for coactivator function than methylation of other substrates. This is not surprising, given that PRMT1 methylates proteins involved in various aspects of RNA metabolism. The fact that the m2, m5, and m7 mutation sites are not localized to a specific small region of the PRMT1 surface (Fig. 8) is consistent with our hypothesis that there are multiple substrate binding sites on the surface of PRMT1, which allow it to methylate diverse substrates. The hypothesis was suggested by the crystal structure which had GAR substrate peptides bound in several different grooves on the PRMT1 surface (6).

We propose that the primary problem for mutants m1, m3, m6, m8, m10 and m13 is reduced or lost ability to form homo-dimers or homo-oligomers and that all of the other aspects of their mutant phenotype derive from the loss of dimerization/oligomerization function. It has been previously established that the ability of PRMT1 to form homo-dimers and/or homo-oligomers is important for its methyltransferase activity (6), and all mutants in this group had substantially reduced methyltransferase function on all substrates tested. The loss of dimerization and methyltransferase activities also probably contributed to lack of coactivator activity among these mutants. However, we cannot make firm conclusions about the coactivator function, since most of the mutants in this class (except for m1) were expressed at reduced levels in mammalian cells. However, note that equivalent amounts of mutant and wild type recombinant proteins were used for all of the other tests. Thus, dimerization may also be important for the stability of the protein in mammalian cells. It is interesting to note that the mutation sites of our dimerization mutants are in two different clusters on the PRMT1 surface. Mutants m1 and m3 are close to the dimer arm docking site (Figs. 1 & 8) and thus could directly affect binding of the dimer arm of one subunit to the docking site on the other subunit. The remainder of the dimerization mutations are located in a region that is distal to the dimer arm and its docking site. We propose that this region may be involved in higher order oligomerization of PRMT1. Since PRMT1 is known to form homo-oligomers, there must be interaction surfaces other than the dimerization arm and docking site to allow the dimers to form higher order oligomers. Disruption of either the dimerization or oligomerization interfaces could cause a reduced signal in our GST pull-down assay.

An unexpected aspect of the mutant phenotype of the dimerization/oligomerization mutants was the increase in their ability to bind GRIP1. Note that every one of the mutants with moderate to severe loss of dimerization/oligomerization exhibited increased GRIP1 binding, while none of the other mutants in this study exhibited more than a slight increase in GRIP1 binding. Also note that there was an inverse correlation in the strength of dimerization/oligomerization and the strength of GRIP1 binding among all of the mutants. These results suggest that dimerization/oligomerization and GRIP1 binding may be mutually exclusive activities. The binding of wild type PRMT1 to GRIP1 is relatively weak, especially when compared with the binding of CARM1 to GRIP1 (Lee, DY. and Stallcup, M.R., unpublished observations). Thus, one possible interpretation of our results is that binding of PRMT1 to GRIP1 may require dissolution or loosening of either the dimer or the oligomer interface of PRMT1. If PRMT1 must dimerize or oligomerize to carry out methyl transfer, but must partly or fully dissociate to bind GRIP1, then a complex (and possibly regulated) dynamic equilibrium of PRMT1 dimerization/oligomerization may be required for PRMT1 to achieve its coactivator function.

In summary, the characterization of surface residues of PRMT1 resulted in several novel insights into the function of PRMT1. We identified surface residues that are important for its methyltransferase activity, substrate specificity, and homo-dimerization. The phenotypes of the mutants further revealed functional relationships among these three properties and between these properties and the ability of PRMT1 to bind GRIP1 and to serve as a coactivator. Most notably, our results suggested that PRMT1 makes one or more currently unknown protein-protein interactions which, in addition to the methyltransferase activity, are critical for the coactivator function of PRMT1. In addition, dimerization/oligomerization of PRMT1 appears to inhibit its binding to GRIP1, since weak GRIP1 binding increased in the mutants with compromised dimerization/oligomerization ability.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

The mutations were generated with the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), using pSG5.HA-PRMT1 (19) as the template. EcoRI-XhoI inserts encoding PRMT1 mutants were then subcloned into the EcoRI-XhoI sites of pGEX4T1 (Pharmacia) to make GST-fusion proteins. Proteins with N-terminal hemagglutinin A (HA) tags were expressed in mammalian cells and in vitro from the pSG5.HA vector, which has SV40 and T7 promoters (25). The following plasmids were described previously (25): pSG5.HA-GRIP1; pSVAR0 encoding human androgen receptor (AR); and MMTV-Luc with the native mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter as a luciferase reporter plasmid for AR.

In vitro Methylation Assay

Recombinant GST fusion proteins were produced in E. Coli BL21 by standard methods using glutathione agarose adsorption. 1−3 μg of recombinant histone H4 was incubated in a final reaction volume of 37.5 μl with 1 μg of GST-PRMT1 and 6 μl of S-adenosyl-L-[methyl-H3]methionine (AdoMet) (14 Ci/mmol) in methylation reaction buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.2 M NaCl, 4 mM EDTA for 1 h at 37°C. Reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Hypo-methylated cell extracts were prepared from MEF cells grown in 10 cm dishes to confluency and then treated with 20 μM Adox for 2 days. Cell extracts were harvested in phosphate buffered saline and sonicated 3 times for 10 sec each at power setting 3 of a Virsonic 600 ultrasonic cell disrupter (Model #274506). Cell extracts were heated at 70°C for 10 min to inactivate endogenous methyltransferases. 10 μl of hypomethylated cell extract was used to perform in vitro methylation with GST-PRMT1.

Protein-Protein Interactions

GST pull down assays were performed with 35S-labeled proteins which were synthesized in vitro by transcription and translation using the TNT-T7 coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega). 1 – 2 μg of GST or GST-fusion protein on glutathione agarose beads (Sigma) or 1 μg of biotin-tagged histone H4 (1-21) peptide (Upstate Biotechnology Inc.) on streptavidinagarose beads was incubated with 10 μl of the in vitro synthesized proteins in 500 μl of NETN buffer (100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 0.01% IGEPAL CA-630) overnight at 4°C with rotation. After washing beads with NETN buffer containing 0.01% NP-40 three times, bound 35S-labeled proteins were eluted from beads with Laemmli sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography or western blot.

Immunoblots were performed as described previously (26). Briefly, COS-7 cells (27) were grown in 100 mm dishes seeded with 1 × 106 cells and transfected with 2.5 μg of the indicated expression plasmids. 48 h after transfection, cell extracts were prepared in 1 ml of RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS) and immunoblots were performed.

Cell Culture and Transient Transfections for coactivator assays

CV-1 cells (27) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Approximately 18 h prior to transfection, 5 × 104 CV-1 cells were seeded into each well of 12 well dishes. Cells were transiently transfected with Targefect (Targeting Systems) according to the manufacturer's protocol; total DNA was adjusted to 1.0 μg by addition of the empty pSG5.HA vector. 4 h after transfection, cells were grown in medium supplemented with 5% charcoal-stripped FBS (Gemini Bioproducts) for approximately 48 h in the presence of 20 nM dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Cell extracts were assayed for luciferase activity with the Promega Luciferase Assay Kit as described previously (25).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Daniel Gerke for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by United States Public Health Service grants DK55274 (to M.R.S) and GM068680 (to X.C.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Multiple independent experiments were performed for each type of assay used to characterize the mutants. The descriptions of mutant phenotypes in the Results is based on the consensus from the multiple experiments. Because only one data set is shown in Results for each type of assay, the descriptions of the mutant phenotype may not exactly match the data shown in a few cases. However, the descriptions of the mutant phenotypes match the summary of mutant phenotypes shown in Table 1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bedford MT, Richard S. Arginine methylation an emerging regulator of protein function. Mol Cell. 2005;18:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee DY, Teyssier C, Strahl BD, Stallcup MR. Role of protein methylation in regulation of transcription. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:147–170. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McBride AE, Silver PA. State of the arg: protein methylation at arginine comes of age. Cell. 2001;106:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00423-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee J, Sayegh J, Daniel J, Clarke S, Bedford MT. PRMT8, a new membrane-bound tissue-specific member of the protein arginine methyltransferase family. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32890–32896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506944200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X, Zhou L, Cheng X. Crystal structure of the conserved core of protein arginine methyltransferase PRMT3. EMBO J. 2000;19:3509–3519. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.14.3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X, Cheng XD. Structure of the predominant protein arginine methyltransferase PRMT1 and analysis of its binding to substrate peptides. Structure. 2003;11:509–520. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00071-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang J, Frankel A, Cook RJ, Kim S, Paik WK, Williams KR, Clarke S, Herschman HR. PRMT1 is the predominant type I protein arginine methyltransferase in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7723–7730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boisvert FM, Cote J, Boulanger MC, Richard S. A Proteomic Analysis of Arginine-methylated Protein Complexes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;2:1319–1330. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300088-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strahl BD, Briggs SD, Brame CJ, Caldwell JA, Koh SS, Ma H, Cook RG, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Stallcup MR, Allis CD. Methylation of histone H4 at arginine 3 occurs in vivo and is mediated by the nuclear receptor coactivator PRMT1. Curr Biol. 2001;11:996–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang H, Huang Z-Q, Xia L, Feng Q, Erdjument-Bromage H, Strahl BD, Briggs SD, Allis CD, Wong J, Tempst P, Zhang Y. Methylation of histone H4 at arginine 3 facilitates transcriptional activation by nuclear hormone receptor. Science. 2001;293:853–857. doi: 10.1126/science.1060781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teyssier C, Ma H, Emter R, Kralli A, Stallcup MR. Activation of nuclear receptor coactivator PGC-1alpha by arginine methylation. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1466–1473. doi: 10.1101/gad.1295005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen EC, Henry MF, Weiss VH, Valentini SR, Silver PA, Lee MS. Arginine methylation facilitates the nuclear export of hnRNP proteins. Genes Dev. 1998;12:679–691. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.5.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henry MF, Silver PA. A novel methyltransferase (Hmt1p) modifies poly(A)+-RNA-binding proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3668–3678. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J, Bedford MT. PABP1 identified as an arginine methyltransferase substrate using high-density protein arrays. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:268–273. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Najbauer J, Johnson BA, Young AL, Aswad DW. Peptides with sequences similar to glycine, arginine-rich motifs in proteins interacting with RNA are efficiently recognized by methyltransferase(s) modifying arginine in numerous proteins. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10501–10509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith JJ, Rücknagel KP, Schierhorn A, Tang J, Nemeth A, Linder M, Herschman HR, Wahle E. Unusual sites of arginine methylation in Poly(A)-binding protein II and in vitro methylation by protein arginine methyltransferases PRMT1 and PRMT3. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13229–13234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.An W, Kim J, Roeder RG. Ordered cooperative functions of PRMT1, p300, and CARM1 in transcriptional activation by p53. Cell. 2004;117:735–748. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rezai-Zadeh N, Zhang X, Namour F, Fejer G, Wen YD, Yao YL, Gyory I, Wright K, Seto E. Targeted recruitment of a histone H4-specific methyltransferase by the transcription factor YY1. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1019–1029. doi: 10.1101/gad.1068003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koh SS, Chen D, Lee Y-H, Stallcup MR. Synergistic enhancement of nuclear receptor function by p160 coactivators and two coactivators with protein methyltransferase activities. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1089–1098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004228200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Reinberg D. Transcription regulation by histone methylation: interplay between different covalent modifications of the core histone tails. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2343–2360. doi: 10.1101/gad.927301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischle W, Wang YM, Allis CD. Histone and chromatin cross-talk. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:172–183. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teyssier C, Chen D, Stallcup MR. Requirement for Multiple Domains of the Protein Arginine Methyltransferase CARM1 in Its Transcriptional Coactivator Function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46066–46072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiss VH, McBride AE, Soriano MA, Filman DJ, Silver PA, Hogle JM. The structure and oligomerization of the yeast arginine methyltransferase, Hmt1. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:1165–1171. doi: 10.1038/82028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang J, Gary JD, Clarke S, Herschman HR. PRMT3, a type I protein arginine N-methyltransferase that differs from PRMT1 in its oligomerization, subcellular localization, substrate specificity, and regulation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16935–16945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen D, Ma H, Hong H, Koh SS, Huang S-M, Schurter BT, Aswad DW, Stallcup MR. Regulation of Transcription by a Protein Methyltransferase. Science. 1999;284:2174–2177. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee Y-H, Koh SS, Zhang X, Cheng X, Stallcup MR. Synergy among nuclear receptor coactivators: selective requirement for protein methyltransferase and acetyltransferase activities. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3621–3632. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3621-3632.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gluzman Y. SV40-transformed simian cells support the replication of early SV40 mutants. Cell. 1981;23:175–182. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]