Abstract

Glucose absorption in rat jejunum involves Ca2+- and PKC βII-dependent insertion of GLUT2 into the apical membrane. Ca2+-induced rearrangement of the enterocyte cytoskeleton is thought to enhance paracellular flow. We have therefore investigated the relationships between myosin II regulatory light chain phosphorylation (RLC20), absorption of glucose, water and calcium, and mannitol clearance. ML-7, an inhibitor of myosin light chain kinase, diminished the phloretin-sensitive apical GLUT2 but not the phloretin-insensitive SGLT1 component of glucose absorption in rat jejunum perfused with 75 mm glucose. Western blotting and immunocytochemistry revealed marked decreases in RLC20 phosphorylation in the terminal web and in the levels of apical GLUT2 and PKC βII, but not SGLT1. Perfusion with phloridzin or 75 mm mannitol, removal of luminal Ca2+, or inhibition of unidirectional 45Ca2+ absorption by nifedipine exerted similar effects. ML-7 had no effect on the absorption of 10 mm Ca2+, nor clearance of [14C]-mannitol, which was less than 0.7% of the rate of glucose absorption. Water absorption did not correlate with 45Ca2+ absorption or mannitol clearance. We conclude that the Ca2+ necessary for contraction of myosin II in the terminal web enters via an L-type channel, most likely Cav1.3, and is dependent on SGLT1. Moreover, terminal web RLC20 phosphorylation is necessary for apical GLUT2 insertion. The data confirm that glucose absorption by paracellular flow is negligible, and show further that paracellular flow makes no more than a minimal contribution to jejunal Ca2+ absorption at luminal concentrations prevailing after a meal.

When glucose is transported into the enterocyte by SGLT1, a major cytoskeletal re-arrangement occurs. Dilatations in tight junctions, thought to reflect an opening or loosening of tight junction structure occur; in addition there are large increases in the size of the intercellular spaces, which provide increased clearance of nutrient from the basolateral membrane into the circulation (Madara & Pappenheimer, 1987). Pappenheimer & Reiss (1987) proposed that opening of the tight junctions permits paracellular flow, in which SGLT1-induced solvent drag of glucose explains the large, non-saturable diffusive component of absorption seen at high glucose concentrations. The idea that transcellular absorption of nutrient from the lumen of the small intestine is augmented by a paracellular component, which provides the major route by which nutrient enters the systemic circulation, is also widely accepted for Ca2+ (Pansu et al. 1983; Bronner et al. 1986; Wasserman & Fullmer, 1995; Bronner, 2003).

Madara & Pappenheimer (1987) proposed that contraction of the perijunctional actomyosin ring (PAMR) is central to cytoskeletal rearrangement and increased paracellular permeability (Atisook et al. 1990). The work of Turner and colleagues has provided clear evidence for the role of PAMR contraction in cytoskeletal rearrangement. Using an in vitro reductionist approach in Caco-2 cells transfected with SGLT1, these workers correlated the signal generated by Na+–glucose cotransport with phosphorylation of the regulatory light chain (RLC20) of myosin II in the PAMR by myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) (Turner et al. 1999; Berglund et al. 2001; Clayburgh et al. 2004). MLCK is a Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent enzyme, implying a connection between glucose absorption by SGLT1, calcium absorption and cytoskeletal rearrangement.

A number of laboratories have reported observations consistent with a new model for intestinal sugar absorption in which the Na+–glucose cotransporter, SGLT1, and the facilitative transporter, GLUT2, work in concert to cover the whole range of physiological glucose concentrations (for a review, see Kellett & Brot-Laroche, 2005). At low glucose concentrations, the primary route of absorption is by SGLT1. However, at high glucose concentrations, glucose transport through SGLT1 induces the rapid insertion of GLUT2 into the apical membrane to provide a large facilitated component of absorption. Apical GLUT2 and SGLT1 together account within experimental error for total glucose absorption, so that apical GLUT2 provides an explanation for the diffusive component (Kellett & Helliwell, 2000; Kellett, 2001; Helliwell & Kellett, 2002). Moreover, as confirmed in the previous paper (Morgan et al. 2007), insertion of apical GLUT2 is mediated by a PKC βII-dependent pathway, emphasizing again the connection between glucose absorption and Ca2+.

Following this connection, we observed the appearance during active glucose absorption of a large component of unidirectional lumen-to-mucosa 45Ca2+ absorption, which could not be mediated by TRPV5/6, since epithelial Ca2+ channels are activated by hyperpolarization. 45Ca2+ absorption displayed functional L-type characteristics and was SGLT1-dependent (Morgan et al. 2003, 2007). The glucose-induced component of 45Ca2+ absorption was most obvious at the physiological concentrations of dietary Ca2+ after a meal, that is, 5–10 mm in the lumen, when there is a substantial transepithelial gradient. We then demonstrated by RT-PCR, Western blotting and immunocytochemistry the presence in the apical membrane of both the major α pore-forming subunit of the non-classical, neuroendocrine L-type calcium channel, Cav1.3, and the auxiliary subunit Cavβ3, which is thought to target the α-subunit to the membrane. The electrophysiological properties of Cav1.3 seem ideal for intestine. It therefore appears that Cav1.3 provides a substantial route of Ca2+ absorption during the assimilation of a meal. In contrast to these findings, it is widely accepted that the major route of intestinal Ca2+ absorption is paracellular (up to 85%) when there is a large transepithelial Ca2+ gradient (reviewed in Bronner, 2003).

Nevertheless, data from different laboratories point clearly to a fundamental intracellular linkage between glucose and Ca2+ absorption, SGLT1 and myosin contraction in the PAMR. Of note, insertion of apical GLUT2 is also dependent on luminal Ca2+ and apical GLUT2, not paracellular flow, now provides an explanation for the diffusive component, which depends on cytoskeletal rearrangement. We have therefore addressed two questions: (1) Does apical GLUT2 insertion depend on myosin contraction and therefore on Ca2+-induced cytoskeletal rearrangement? (2) When there is a large transepithelial gradient at Ca2+ concentrations within the dietary physiological range, and given that TRPV5/6 and Cav1.3 may then both contribute to absorption, what contribution does paracellular flow make to Ca2+ absorption? We have explored these questions using glucose and ML-7, an inhibitor of MLCK, to control myosin phosphorylation, and have correlated changes in glucose and 45Ca2+ absorption with changes in water flow and clearance of 14C-mannitol as a permeability probe for paracellular flow.

Methods

All experimental details have been described in some detail previously (Kellett & Helliwell, 2000; Morgan et al. 2003). Only significant modifications are described below.

Perfusion of jejunal loops in vivo

[14C]-mannitol (0.5 kBq ml−1) was used as a non-transportable permeability probe. The counting protocol for [3H]-inulin, 45Ca2+ and [14C]-mannitol was automatically corrected for cross-channel interference. 1-(5-iodonaphthalene-1-sulphonyl)homopiperazine-HCl (5 μm ML-7, Calbiochem), a cell-permeable and potent inhibitor of myosin light chain kinase activity was used to inhibit myosin light chain kinase activity.

Isolation of apical membrane vesicles and cytosol

When mucosa was homogenized under conditions which minimized proteolysis and prevented trafficking of GLUT2 away from the apical membrane, the phosphorylation status of the proteins was maintained by addition of 10 mm EDTA, 200 mm activated sodium orthovanadate, 20 mm NaF, 10 mm EGTA and 5 mm EDTA to the homogenization buffer. A cytosolic fraction was retained from the initial homogenate preparation; this fraction, which was the supernatant after centrifugation for 2 min at 13 000 g in a TL100 Beckman centrifuge, contained the majority of terminal web myosin II. Vesicles were prepared from the remaining homogenate and their purity was assessed as before (Corpe et al. 1996; Helliwell et al. 2000).

SDS-PAGE analysis and Western blotting

Antibody raised to a synthetic phosphopeptide corresponding to residues surrounding the amino acid residue Ser19 (Cell Signalling Technology, Inc.) was used to immunoblot phosphorylated myosin II RLC20. For total myosin II RLC20, the antibody was raised in goat to a synthetic peptide mapping to the amino terminus of myosin II RLC20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Specificity of staining was confirmed for both antibodies by neutralization with excess antigenic peptide (antibody to peptide 1: 1 v/v, peptide 50 μg ml−1). Phosphorylation of myosin II RLC20 was assessed by calculating the ratio of the anti-phospho (Ser19) myosin II RLC20 signal to the anti-total myosin II RLC20.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. and were tested for significance using either paired or unpaired Student's t test where appropriate.

Results

Contraction of myosin II is required for GLUT2-mediated glucose absorption in vivo

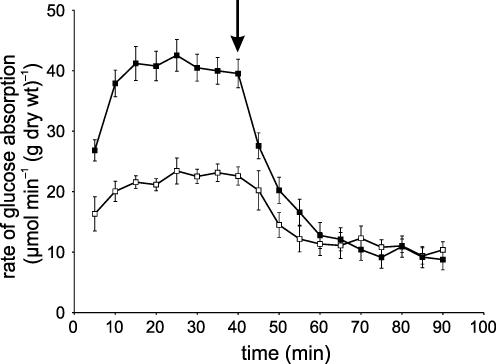

Rat jejunum was perfused in single-pass mode in vivo with 75 mm glucose (control perfusion). The rate of absorption increased between 5 and 15 min to a steady state, indicating up-regulation of glucose absorption by luminal glucose (Fig. 1). This steady state could be maintained for 80–90 min (data not shown). Addition of 1 mm phloretin at 40 min, which inhibits GLUT2 but not SGLT1 in whole intestine, diminished the rate of absorption by 74.8% from 38.48 ± 2.37 to 9.68 ± 1.76 μmol min−1 (g dry wt)−1, respectively (Fig. 1). The values of the GLUT2 (phloretin-sensitive) and SGLT1 (phloretin-insensitive) components are very similar to those previously reported; the use of cytochalasin B, or phloridzin or replacement of Na+ with choline (no inhibitors) gave the same quantitative data (Kellett & Helliwell, 2000; Helliwell & Kellett, 2002). ML-7 is a cell-permeable and potent inhibitor of Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent myosin light chain kinase, activation of which causes phosphorylation of Ser19 of RLC20 and ensuing contraction of the actomyosin complex. Introduction of 5 μm ML-7 into the luminal perfusate at 40 min caused a 42.4% decrease in the absorption of glucose (22.17 ± 1.47 μmol min−1(g dry wt)−1; P < 0.001). Phloretin (1 mm) diminished this rate to 10.78 ± 1.41 μmol min−1 (g dry wt)−1. It is therefore apparent that ML-7 affects the GLUT2 but not the SGLT1 component of glucose absorption.

Figure 1. The effect of MLCK inhibition on glucose absorption across the in vivo luminally perfused rat jejunum.

Rat jejunum was perfused in vivo with 75 mm glucose as control (▪) and 5 μm ML-7 (□) as described in the Methods section. At 40 min, the perfusate reservoir was switched (arrow) to an identical one containing 1 mm phloretin. Values are the mean rate of glucose absorption from 6 experiments. Error bars represent s.e.m.

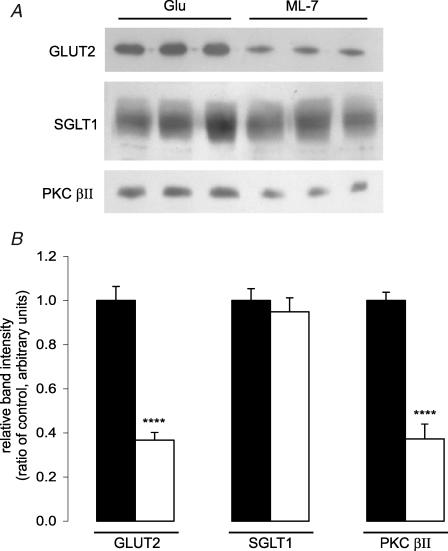

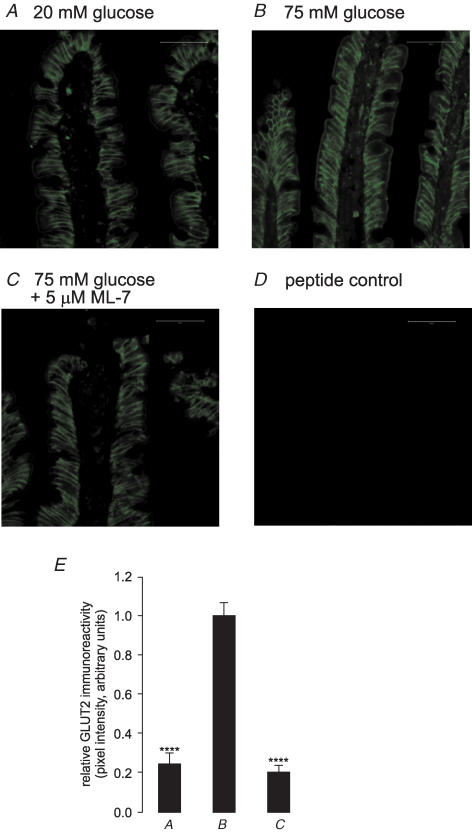

In order to correlate the observed changes in glucose absorption with changes in transporter levels, intestine was perfused for 30 min with 75 mm glucose in the presence and absence of 5 μm ML-7; apical membrane vesicles were then prepared and cytosolic proteins extracted. Western blotting revealed that ML-7 caused a 63.3 ± 3.51% reduction (P < 0.001) in apical GLUT2 levels determined with C-terminal antibody and a 62.7 ± 6.7% reduction (P < 0.001) in the native 80 kDa PKC βII level (Fig. 2). There was no significant attenuation of the level of SGLT1 protein (5.1 ± 6.3%; P=0.61 versus control). All bands were eliminated when antibodies were pre-incubated in an excess of antigenic peptide, confirming the specificity of staining (data not shown). Prior to immunocytochemistry, jejunum was fixed in situ during perfusion with 75 mm glucose with or without ML-7; the section was subsequently deglycosylated with endoglycosidase F and probed with antibody to the extracellular loop of GLUT2. ML-7 diminished the level of GLUT2 immunoreactivity at the apical membrane by 69.4 ± 2.3% (P < 0.001; Fig. 3), in good agreement with the Western blots.

Figure 2. Effect of ML-7 on the protein levels of GLUT2, SGLT1 and PKC βII in the brush-border membrane.

Vesicles were prepared from the jejunum of rats perfused for 30 min with either 75 mm glucose (Glu) as control or 75 mm glucose and 5 μm ML-7 (ML-7). A, vesicle protein (20 μg) was separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels, transblotted onto PVDF and Western blotted with GLUT2, SGLT1 and PKC βII antibodies. B, expression of protein levels relative to 75 mm glucose control determined from three separate preparations using two rats each. ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired Student's t test.

Figure 3. Apical GLUT2-like immunoreactivity in response to 75 mM glucose is abolished by ML-7.

Frozen sections of rat jejunum were prepared after perfusion in vivo of the lumen with 20 mm glucose (A), 75 mm glucose (B) or 75 mm glucose and 5 μm ML-7 (C). Sections of 7 μm were probed with anti-GLUT2 antibody. The secondary antibody was a FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. The peptide control (D) was a section of jejunum treated with 75 mm glucose and antibody that had been pre-absorbed with excess antigenic peptide. All sections are at × 40 magnification and were taken at the same settings with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope; scale bars, 50 μm. E, relative pixel intensity values are expressed relative to the 75 mm glucose as control ± s.e.m. where n=3. ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired Student's t test.

Phosphorylation of myosin II RLC20

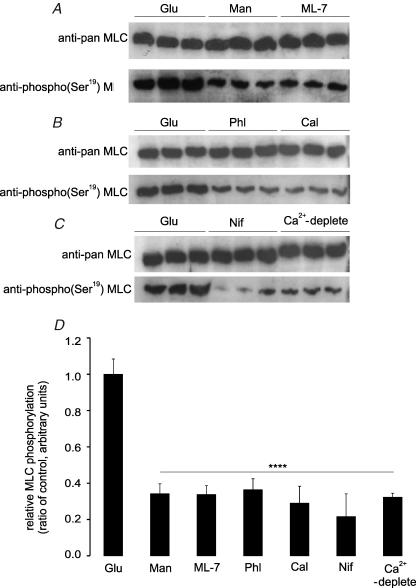

Phosphorylation of the RLC20 of myosin II in the cytosolic extracts prepared after homogenization was used as a biochemical indicator of actomyosin contraction; myosin released during solubilization is derived almost exclusively from the terminal web (Mooseker, 1985). Western blots were probed with an anti-phospho(Ser19) myosin light chain (MLC) specific antibody and an anti-pan MLC antibody. The ratio of the two signals was used to evaluate phosphorylation of the RLC20 of myosin II. For jejunum perfused for 30 min with 75 mm glucose (control), the ratio of phospho to pan signals was normalized to 1.00 (± 0.08, n=3 separate preparations). This ratio fell to 0.34 ± 0.03 and 0.33 ± 0.03 for perfusion with 75 mm mannitol or with 75 mm glucose and 5 μm ML-7, respectively (Fig. 4A; both P < 0.0001 and n=3 separate preparations each). At high glucose concentrations, therefore, insertion of apical GLUT2 correlates with increased phosphorylation of RLC20 in rat jejunum. When jejunum was perfused for 30 min with 75 mm glucose and 0.2 mm phloridzin, the ratio of phospho to pan signals relative to that with 75 mm glucose alone (control) was just 0.36 ± 0.06, demonstrating that phosphorylation was dependent on glucose transport through SGLT1 (Fig. 4B; P < 0.0001 and n=3 separate preparations). The importance of calmodulin in mediating the activation of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) in response to glucose in rat jejunum was indicated by inhibition of phosphorylation after rat jejunum was perfused with 75 mm glucose and the calmodulin inhibitor calmidazolium (20 μm); for calmidazolium, the ratio relative to control was just 0.29 ± 0.09 (Fig. 4B; P < 0.0001 and n=3 separate preparations each). Bands detected by both anti-pan and anti-phospho(Ser19) antibodies were eliminated by pre-incubation with excess of the antigenic peptide (data not shown, but see immunocytochemistry). Blocking the phosphorylation of the RLC20 of myosin II by perfusion with mannitol, ML-7, phloridzin or calmidazolium correlates with inhibition of apical GLUT2 insertion.

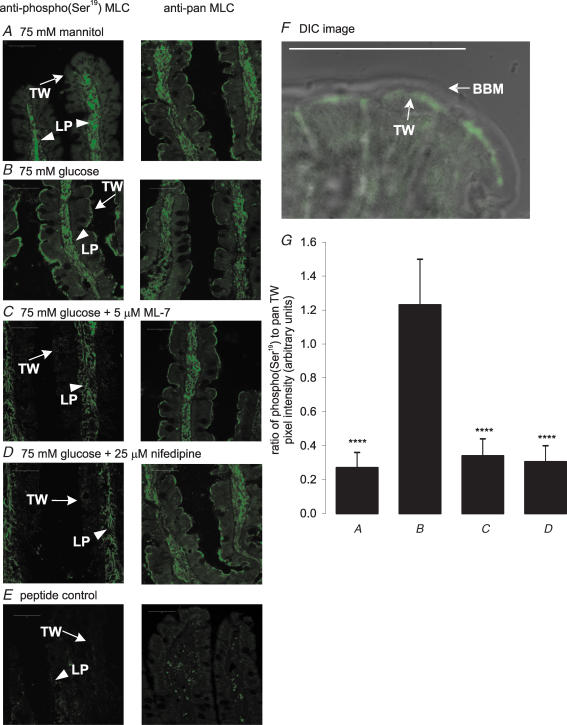

Figure 4. The effect of glucose, ML-7, phloridzin, calmidazolium, nifedipine and luminal Ca2+ on phosphorylation of myosin II RLC20.

Rat jejunum was perfused for 30 min with either 75 mm glucose (Glu) as control, 75 mm mannitol (Man), 75 mm glucose and 5 μm ML-7 (ML-7), 75 mm glucose and 0.2 mm phloridzin (Phl), 75 mm glucose and 20 μm calmidazolium (Cal), 75 mm glucose and 10 μm nifedipine (Nif) or 75 mm glucose in a perfusate deplete of Ca2+ (Ca2+-deplete). A–C, protein (20 μg) was separated on 12% SDS-PAGE gels, transblotted onto PVDF membrane and Western blotted with anti-pan and anti-phospho(Ser19) myosin II RLC20 antibodies. D, expression of the ratio of phospho(Ser19) to pan signal determined from the band intensity of three separate preparations using two rats each. ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired Student's t test.

Immunocytochemistry using the anti-pan antibody to probe sections from jejunum revealed that the RLC20 of myosin II had dual location (Fig. 5): it was localized to the lamina propria (LP) core of the villus, presumably in smooth muscle, and also in the terminal web (TW). Labelling using the phospho(Ser19) antibody was effectively restricted to low levels in the lamina propria core of the non-absorptive villus in the presence of 75 mm mannitol (Fig. 5A), but was strongly increased in the terminal web in the absorptive state with 75 mm glucose (Fig. 5B). The ratio of the anti-phospho(Ser19) and anti-pan signals for MLC localized in the terminal web was 1.00 ± 0.13 at 75 mm glucose, but just 0.10 ± 0.03 (P < 0.001) at 75 mm mannitol. Figure 5F shows a differential interference contrast image (DIC) at 75 mm glucose confirming the presence of phosphorylated myosin II in the terminal web. Blocking MLCK activity by addition of ML-7 to the perfusate in the presence of 75 mm glucose diminished the ratio of phospho(Ser19) to pan signals at the apical domain to just 0.09 ± 0.02 (P < 0.001; Fig. 5C); there was no effect on phosphorylation in the lamina propria. Labelling of both pan and phospho(Ser19) RLC20 was eliminated by pre-incubation of antibodies with excess cognate peptide (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5. Immunolocalization of phospho(Ser19) RLC20 and pan RLC20 of myosin II in rat jejunum.

Frozen sections of rat jejunum were prepared after perfusion with 75 mm mannitol (A), 75 mm glucose (B), 75 mm glucose and 5 μm ML-7 (C) or 75 mm glucose and 10 μm nifedipine (D). Sections 7 μm thick were probed with anti-pan and anti-phospho(Ser19) myosin II RLC20 antibody. Binding was visualized with a secondary goat or rabbit antibody conjugated to FITC; myosin II was located in the terminal web (TW) and lamina propria (LP). The peptide controls (E) were sections from jejunum perfused with 75 mm glucose and incubated with primary antibodies that had been pre-absorbed with excess antigenic peptides. All sections are at × 40 magnification and were taken at the same settings with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope; scale bars, 50 μm. F, differential interference contrast (DIC) image at 75 mm glucose with anti-phospho(Ser19) antibody confirming that phosphorylated myosin II (green) is located in the terminal web. G, pixel intensity values are expressed as the ratio of anti-phospho(Ser19) to pan relative to the 75 mm glucose as control as determined from three separate preparations ± s.e.m. where n=3. ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired Student's t test.

Extracellular Ca2+ is required for MLCK activity

Inhibition of apical GLUT2 insertion by inhibition of MLCK with ML-7 correlates with inhibition of PKC βII and RLC20 phosphorylation (Figs 2 and 4). Both PKC βII and MLCK are Ca2+-dependent enzymes. Moreover, we have reported that SGLT1-induced Ca2+ influx displays L-type characteristics most probably mediated by Cav1.3 (Morgan et al. 2003, 2007). We therefore wished to establish whether ML-7 has any effect on Ca2+ entry and whether luminal Ca2+ entry controls MLC phosphorylation. ML-7 (5 μm) had no significant effect on 45Ca2+ absorption in the presence of 75 mm glucose (P=0.72; Fig. 6). This observation confirms that ML-7 acts exclusively downstream of Ca2+ entry, consistent with its known action on MLCK. In agreement with our previous work, the addition of nifedipine (10 μm) at 40 min to the perfusate containing 75 mm glucose inhibited unidirectional 45Ca2+ absorption by 46.5% from 0.208 ± 0.011 to 0.141 ± 0.015 μmol min−1 (g dry wt)−1 (P < 0.01; Fig. 6). In Western blots of cytosolic extracts, nifedipine and Ca2+ depletion diminished the ratio of phospho(Ser19) to pan signals relative to 75 mm glucose alone (control) to 0.22 ± 0.13 and 0.32 ± 0.02, respectively (Fig. 4C; both P < 0.0001 and n=3 separate preparations). Immunocytochemistry confirmed that the effect of nifedipine was confined to the terminal web (Fig. 5D); the ratio of phospho(Ser19) to pan signals was diminished from 1.00 ± 0.13 to just 0.25 ± 0.08 (P < 0.0001; Fig. 5G). At 75 mm glucose, omission of Ca2+ from the luminal perfusate (Ca2+ deplete) exerted the same effect on RLC20 phosphorylation as described for nifedipine (Figs 4 and 5).

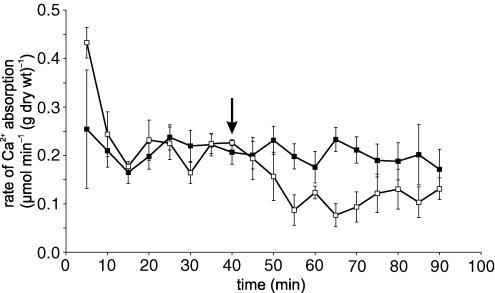

Figure 6. The effect of ML-7 and nifedipine on unidirectional 45Ca2+ absorption.

Rat jejunum was perfused in vivo with 75 mm glucose and 1.25 mm Ca2+ (45Ca2+ 0.35 kBq ml−1). At 40 min, the perfusate was switched (arrow) to an identical one containing either 5 μm ML-7 (▪) or 10 μm nifedipine (□). Values are presented as the average rate of absorption from 5 experiments. Error bars represent s.e.m.

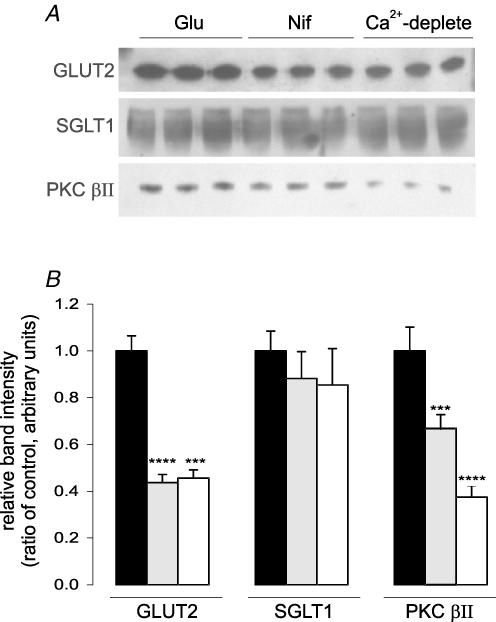

The effect of luminal Ca2+ on apical GLUT2 trafficking was investigated by preparing apical membrane vesicles from jejunum perfused with 75 mm glucose for 30 min in the presence and absence of nifedipine and also with 75 mm glucose in Ca2+-deplete perfusate. The two conditions diminished the apical GLUT2 band intensity by 56.3 ± 3.5% (P < 0.0001) and 54.4 ± 3.5% (P < 0.001), respectively (both n=3 separate preparations; Fig. 7A); PKC βII band intensity was correspondingly decreased by 47.9 ± 6.5% (both P < 0.001) and 42.6 ± 4.5% (P < 0.0001), respectively (both n=3 separate preparations; Fig. 7A). We have previously reported very similar blots to those for GLUT2, PKC βII and SGLT1 in Fig. 7A in response to perfusion with nifedipine or Ca2+-deplete conditions (Morgan et al. 2007). The difference is that the vesicles used for Fig. 7 were prepared in the presence of a cocktail of inhibitors designed to prevent changes in phosphorylation. Thus, the standard ice-cold procedures that we have previously used to prevent changes in apical GLUT2 trafficking also prevent potential changes in transporter levels by alteration in phosphorylation during purification.

Figure 7. The effect of luminal Ca2+ on apical GLUT2, SGLT1 and PKC βII protein levels.

Apical membrane vesicles were prepared from the jejunum of rats following perfusion for 30 min with 75 mm glucose (Glu) as control; 75 mm glucose and 10 μm nifedipine (Nif) or 75 mm glucose and a perfusate without luminal Ca2+ (Ca2+-deplete). A, protein (20 μg) was separated using 10% SDS-PAGE gels, transblotted onto PVDF membrane and Western blotted for GLUT2, SGLT1 and PKC βII. B, expression of protein levels relative to 75 mm glucose control determined from three separate preparations using two rats each. ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired Student's t test.

Jejunal permeability and paracellular flow

Glucose-induced ‘loosening’ of the tight junctions is widely reported to increase intestinal permeability and paracellular flow of nutrients by solvent drag (Pappenheimer & Reiss, 1987; Turner, 2000a,b). Moreover, the major route of Ca2+ absorption is thought to occur by paracellular flow (Bronner, 2003). We therefore sought to test these proposals in rat jejunum using glucose and ML-7 to control tight junction permeability through actomyosin contraction and relaxation, respectively. In order to understand the design of these experiments, it is helpful to know that at 75 mm mannitol, or at 10 and 20 mm glucose balanced to a total sugar concentration of 75 mm with mannitol, there is a basal level of apical GLUT2 of low activity in fed rats. At 75 mm glucose, there is a large apical GLUT2 component of absorption reflecting substantial additional insertion of GLUT2 of high activity associated with cytoskeletal rearrangement.

This set of experiments was performed with 10 mm Ca2+ in the lumen comparable to that arriving after a meal (Bronner, 2003), so that there was a substantial transepithelial concentration gradient for Ca2+, a prerequisite of paracellular flow. Table 1 depicts the relationships between glucose absorption, 45Ca2+ absorption, 14C-mannitol clearance and net fluid transport. The rates of glucose absorption at 10 mm Ca2+ were very similar to those previously reported when rat jejunum was perfused with otherwise identical perfusates containing 1.25 mm Ca2+ (Kellett & Helliwell, 2000). At 10 mm Ca2+ (Table 1), there was no effect of glucose on 14C-mannitol clearance, despite the fact that water transport almost doubled from 0 mm (75 mm mannitol) to 75 mm glucose (0 mm mannitol). A glucose-induced stimulation of 45Ca2+ absorption was observed by perfusion with 20 mm glucose, which increased the rate of 45Ca2+ absorption approximately 2-fold compared with 75 mm mannitol (1.184 ± 0.227 and 0.545 ± 0.118 μmol min−1 (g dry wt)−1, respectively; P < 0.001). However, there was no concomitant increase in 14C-mannitol clearance or in water absorption, consistent with the view that paracellular flow plays no role in the absorption of either nutrient at lower glucose concentrations. Moreover, no significant increase in 45Ca2+ absorption occurred between 20 and 75 mm glucose, despite a 2-fold increase in water absorption. Thus, jejunal Ca2+ absorption is completely dissociated from water absorption, which correlates with apical GLUT2 insertion.

Table 1.

The rates of absorption of glucose, 45Ca2+, water and clearance of 14C-mannitol at different glucose concentrations

| Perfusate composition | Glucose | 45Ca2+ | 14C-mannitol | Net fluid transport | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75 mm mannitol | — | 0.545 ± 0.118 | 0.214 ± 0.091 | 0.080 ± 0.021 | 4 |

| + ML-7 | — | 0.445 ± 0.069 | 0.257 ± 0.081 | 0.062 ± 0.007 | |

| 10 mm glucose | 4.846 ± 0.388 | 0.607 ± 0.089 | 0.238 ± 0.051 | 0.071 ± 0.012 | 4 |

| + ML-7 | 5.084 ± 0.584 | 0.496 ± 0.095 | 0.278 ± 0.089 | 0.089 ± 0.013 | |

| 20 mm glucose | 13.415 ± 1.087 | 1.184 ± 0.227$$$ | 0.227 ± 0.092 | 0.108 ± 0.021 | 4 |

| + ML-7 | 12.884 ± 1.024 | 1.074 ± 0.244 | 0.284 ± 0.071 | 0.099 ± 0.017 | |

| 75 mm glucose | 42.242 ± 3.920 | 1.269 ± 0.263$$$ | 0.216 ± 0.084 | 0.142 ± 0.029$$$ | 4 |

| + ML-7 | 21.531 ± 3.589 **** | 1.298 ± 0.179 | 0.234 ± 0.082 | 0.052 ± 0.034*** |

Rats were perfused for 40 min with substrates as required and 10.0 mm Ca2+. At 40 min, the perfusate reservoirs were switched to identical ones containing 5 μm ML-7. Substrate absorption is expressed as μmol min−1 (g dry wt)−1 and water transport expressed as ml min−1 (g dry wt)−1. Values are given as means ± s.e.m. with the number of experiments, n

P < 0.001 by unpaired Student's t test versus 75 mm mannitol

P < 0.001

P < 0.0001 by paired Student's t test.

At 10 mm Ca2+, inhibition of cytoskeletal rearrangement by ML-7 inhibited glucose absorption only at 75 mm glucose, when it prevented additional apical GLUT2 insertion and caused water absorption to return to basal levels. ML-7 had no effect on the clearance of 14C-mannitol at any glucose concentration. Predictably, ML-7 also failed to alter either the basal or the glucose-stimulated rates of 45Ca2+ absorption, an observation consistent with the conclusion that there was no significant paracellular component of Ca2+ absorption.

Discussion

Apical GLUT2 insertion is coupled to myosin II phosphorylation in the terminal web by an L-type calcium channel

SGLT1 and apical GLUT2 together account for glucose absorption at high concentrations; apical GLUT2 therefore provides an alternative explanation to paracellular flow for the diffusive component (Kellett & Helliwell, 2000; Helliwell & Kellett, 2002). Our results now suggest that apical GLUT2 insertion requires cytoskeletal rearrangement of the enterocyte induced by myosin II RLC20 phosphorylation similar to that originally proposed for paracellular flow.

Previous studies on enterocyte cytoskeletal rearrangement have focused on the role of the PAMR, the circumferential ring linked directly to the tight junction (Madara & Pappenheimer, 1987; Pappenheimer & Reiss, 1987; Turner et al. 1997, 1999; Berglund et al. 2001; Clayburgh et al. 2004) In this view, transport of glucose through SGLT1 is associated with a major cytoskeletal rearrangement, such that dilatation of tight junctions occurs and the intercellular spaces are opened to permit paracellular flow and rapid clearance of glucose from the basolateral membrane. We have focused on the role of the terminal web in apical GLUT2 insertion, because there is clear evidence that the terminal web is a staging post in apical GLUT2 translocation (Au et al. 2002; Habold et al. 2005). Moreover, activation of PKC βII, which correlates with apical GLUT2 insertion, has also been detected in the terminal web (Saxon et al. 1994). The terminal web sits below the tight junction, where it makes extensive connections to the adherens junction, as well as further connections to the apical membrane. It therefore seems that contraction of the terminal web occurs simultaneously with that of the PAMR and that the two events represent different aspects of the global cytoskeletal rearrangement.

At 75 mm glucose, there is substantial additional insertion of apical GLUT2 over the basal level at low concentrations of glucose; see Fig. 1 and previous publications (Kellett & Helliwell, 2000; Kellett, 2001). ML-7 is a potent and cell-permeable inhibitor of MLCK and therefore directly inhibits phosphorylation of the RLC20 of myosin II and actomyosin contraction. In rat jejunum, ML-7 inhibited total glucose absorption by 42%, which reflected a diminution of 62% in both the magnitude of apical GLUT2 absorption (Fig. 1) and GLUT2 level, as well as in PKC βII level (Figs 2 and 3). There was no significant effect of ML-7 on the SGLT1 component of absorption or on SGLT1 level. ML-7 had no effect on glucose absorption at relatively low glucose concentrations (Table 1), at which there is only the basal level of apical GLUT2 seen with mannitol alone. ML-7 therefore only blocks the additional insertion of apical GLUT2 seen at high glucose concentrations.

The majority of myosin in the brush-border cytoskeleton is located in the terminal web and some 80% of terminal web myosin is released into the cytoplasmic fraction upon homogenization; the soluble myosin is primarily myosin II, which forms cross-links between microfilaments (Mooseker, 1985). In order to study phosphorylation of terminal web myosin II by MLCK, cytosolic fractions were prepared in the presence of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation inhibitors. The Western blots of cytosolic fractions in Fig. 4 show that Ser19 phosphorylation at 75 mm glucose is some 3-fold that when cytoskeletal rearrangement is prevented by blocking MLCK with ML-7, or by switching perfusate from 75 mm glucose to 75 mm mannitol, or by Ca2+ depletion. Moreover, phosphorylation is dependent on glucose transport through SGLT1, being strongly inhibited by phloridizin. These observations are consistent with the view that under depolarizing conditions at high glucose concentrations, transport of glucose through SGLT1 depolarizes the apical membrane to enhance entry of luminal Ca2+ through Cav1.3 (Morgan et al. 2003). In contrast to nifedipine, ML-7 had no inhibitory effect on 45Ca2+ absorption, yet blocked phosphorylation; thus the source of Ca2+ providing the necessary increase in cytosolic Ca2+ to effect phosphorylation must be upstream of MLCK, that is, Ca2+ entry via Cav1.3. Furthermore, both nifedipine and Ca2+ depletion strongly diminished both apical GLUT2 and PKC βII levels (Fig. 7). Immunocytochemistry reveals dual location of myosin II (Fig. 5). There is substantial labelling in the lamina propria, presumably smooth muscle, and significant labelling in the terminal web. The effects of mannitol, glucose, ML-7 and nifedipine on terminal web myosin phosphorylation seen in Western blots were confirmed completely by immunocytochemistry.

Jejunal glucose and Ca2+ absorption are transcellular

A key feature of the theory of paracellular flow is solvent drag, the idea that water transport drives nutrient absorption. In the past, some reports disputing the contribution of paracellular flow to nutrient absorption have been refuted on the grounds that significant water absorption was not achieved in those experiments (Fine et al. 1993; Soergel, 1993; Schwartz et al. 1995; Uhing & Kimura, 1995; Lane et al. 1999; Turner, 2000a,b). In contrast, high rates of water transport were achieved in the in vivo single-pass perfusion technique used in the present acute experiments; indeed, in a typical perfusion at 75 mm glucose, water absorption at a rate of 0.142 ± 0.029 ml min−1 (g dry wt)−1 equates over a 90 min perfusion to 4.5 ml water, or almost 10% of the extracellular fluid. Water flow is therefore in principle more than adequate to support paracellular flow by solvent drag of nutrient.

Data for water flow and 14C-mannitol clearance nevertheless indicate no significant paracellular flow of glucose. Over the entire range of glucose concentrations at 10 mm Ca2+, there is no change in 14C-mannitol clearance when used as tracer for glucose (0, 10, 20, 75 mm balanced osmotically to a total sugar concentration of 75 mm with mannitol). Moreover, the rate of 14C-mannitol clearance is independent of water absorption and, at 75 mm glucose, was just 0.7% that of the rate of glucose absorption. At 75 mm glucose, water absorption is increased above the basal level with mannitol alone; ML-7 only inhibits water absorption at 75 mm glucose, when apical GLUT2 insertion is blocked. The finding that glucose absorption and water transport can be dissociated is in agreement with the work of Gruzdkov and colleagues, who have reported that high rates of glucose absorption can occur in the face of water secretion induced under hypertonic conditions (Gruzdkov & Gromova, 2001).

It is widely accepted that some 85% of all Ca2+ absorption occurs in jejunum and ileum. In the absence of other nutrients, absorption of Ca2+ is a linear function of concentration up to 200 mm (Bronner, 2003). The apparent consistency of the kinetics with diffusion has led to the view that absorption is largely paracellular, in the same way as originally envisaged for glucose. However, the present data suggest that jejunal absorption is predominantly transcellular, even when sufficient glucose is present to induce cytoskeletal rearrangement and when there is also a large transepithelial gradient of Ca2+. The data in Table 1 were collected at 10 mm luminal Ca2+ and cover a range of glucose concentrations from 0 mm (75 mm mannitol), where there is little phosphorylation of the RLC20 of myosin II in the terminal web and therefore little, if any, actomyosin contraction, to 75 mm glucose, where there is extensive phosphorylation and contraction (Figs 4 and 5). In particular, blocking of myosin phosphorylation and cytoskeletal rearrangement with ML-7 has no effect on Ca2+ absorption under any condition, especially at high glucose (Fig. 6 and Table 1). Moreover, as noted above, the source of Ca2+ required for MLCK activity and myosin phosphorylation is entry of luminal Ca2+ via Cav1.3, that is, it is upstream of MLCK and channel-mediated. The total rates of Ca2+ absorption under different conditions vary 2.6-fold, yet there is no change in 14C-mannitol clearance, which is so low that it might even be attributed to non-specific absorption. In addition, 45Ca2+ absorption is not dependent on water absorption and cannot be attributed to solvent drag (Table 1).

What then of the basal component of 45Ca2+ absorption in the presence of mannitol, which is identified with the nifedipine- and phloridzin-insensitive component (Morgan et al. 2007)? In keeping with our observation that 45Ca2+ absorption can be dissociated from water absorption, Younoszai & Nathan (1985) reported that basal Ca2+ absorption did not occur by a solvent drag mechanism, since a 5-fold increase in water absorption between isotonic and hypotonic conditions had no effect on 45Ca2+ absorption in rat jejunum with 3 mm Ca2+ but no glucose in the lumen: in contrast, under isotonic conditions, 15 mm glucose augmented the rate of Ca2+ absorption by 50% over basal. Similar conclusions were reached by Norman et al. (1980), Fine et al. (1993) and Auchere et al. (1997). The implication that the nifedipine- and phloridzin-insensitive component is channel-mediated is supported by the fact that it is also present when the luminal Ca2+ concentration is 1.25 mm, the same as that of free Ca2+ in plasma (Morgan et al. 2003, 2007). Given their location in the uppermost reaches of the gastrointestinal tract, TRPV6 (CaT1) and, to a lesser extent, TRPV5 (ECaC) may be candidates (Hoenderop et al. 2000; Zhuang et al. 2002). Indeed, since there is likely to be significant recycling of Ca2+ across the epithelium, especially under hyperpolarizing conditions when there is little dietary nutrient in the lumen, a channel with the properties of TRPV5/6 would act to prevent excessive loss of body Ca2+: TRPV5/6 and Cav1.3 surely have complementary roles.

The view that Ca2+ absorption is largely paracellular was based on kinetic measurements up to 200 mm; yet the maximum Ca2+ concentration in the lumen after a meal is within the range 5–10 mm (Bronner, 2003). In light of our present observations at 10 mm luminal Ca2+, we can only conclude that paracellular flow makes little, if any, contribution to Ca2+ absorption within the dietary range and under the depolarizing conditions associated with digestion. How then might diffusive kinetics of Ca2+ absorption be explained? The expected channel-mediated saturable component is presumably obscured by inhibitory mechanisms at high Ca2+ concentrations. Several mechanisms can be envisaged for different channels: rapid trafficking of a channel away from the membrane may occur, as observed for Cav1.3 at high cytosolic Ca2+ in INS-1 cells by Huang et al. (2004); surface charge screening by Ca2+ shifts the current–voltage activation curve of Cav1.3 to more positive voltages at higher Ca2+ concentrations (Xu & Lipscombe, 2001); alternatively, direct inhibition of the channel by cytosolic Ca2+ may result in diffusive kinetics as proposed for TRPV5/6 by Slepchenko & Bronner (2001).

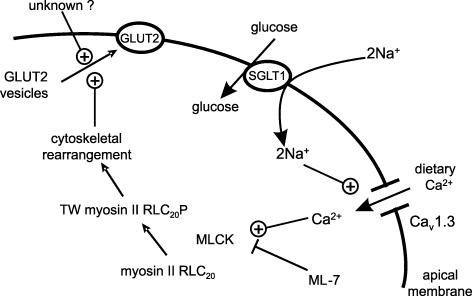

Conclusion

The data are consistent with the following sequence of events (Fig. 8). Glucose transport by SGLT1 causes depolarization of the apical membrane, so that glucose induces a nifedipine-sensitive influx of luminal Ca2+ through a voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channel, most probably Cav1.3. The resulting increase in cytosolic Ca2+ activates the Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent MLCK enzyme, which activates myosin II in the terminal web (TW) by phosphorylation (P) of the RLC20 at Ser19. Contraction and cytoskeletal rearrangement permits translocation of GLUT2 through the terminal web, which is a staging post for GLUT2-containing storage vesicles, to the apical membrane; translocation requires a second, unknown signal. Within the dietary range of luminal Ca2+ concentrations up to 10 mm, paracellular flow of Ca2+ appears to make no more than a minimal contribution to absorption. Glucose and Ca2+ absorption are fundamentally integrated with mutually dependent signalling roles to allow both absorptive capacities to be rapidly and precisely regulated to match dietary intake, without compromising the barrier function of the mucosa.

Figure 8.

Activation of Cav1.3 by glucose transport through SGLT1 links dietary Ca2+ to terminal web myosin II RLC20 phosphorylation, cytoskeletal rearrangement and apical GLUT2 insertion.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust. O.J.M. was the recipient of a BBSRC studentship.

References

- Atisook K, Carlson S, Madara JL. Effects of phlorizin and sodium on glucose-elicited alterations of cell junctions in intestinal epithelia. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:C77–C85. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.1.C77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au A, Gupta A, Schembri P, Cheeseman CI. Rapid insertion of GLUT2 into the rat jejunal brush-border membrane promoted by glucagon-like peptide 2. Biochem J. 2002;367:247–254. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchere D, Tardivel S, Gounelle JC, Lacour B. Stimulation of ileal transport of calcium by sorbitol in in situ perfused loop in rats. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1997;21:960–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund JJ, Riegler M, Zolotarevsky Y, Wenzl E, Turner JR. Regulation of human jejunal transmucosal resistance and MLC phosphorylation by Na+-glucose cotransport. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1487–G1493. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.6.G1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner F. Mechanisms of intestinal calcium absorption. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:387–393. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner F, Pansu D, Stein WD. An analysis of intestinal calcium transport across the rat intestine. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:G561–G569. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1986.250.5.G561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayburgh DR, Rosen S, Witkowski ED, Wang F, Blair S, Dudek S, Garcia JG, Alverdy JC, Turner JR. A differentiation-dependent splice variant of myosin light chain kinase, MLCK1, regulates epithelial tight junction permeability. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55506–55513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408822200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpe CP, Basaleh MM, Affleck J, Gould G, Jess TJ, Kellett GL. The regulation of GLUT5 and GLUT2 activity in the adaptation of intestinal brush-border fructose transport in diabetes. Pflugers Arch. 1996;432:192–201. doi: 10.1007/s004240050124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine KD, Santa Ana CA, Porter JL, Fordtran JS. Effect of d-glucose on intestinal permeability and its passive absorption in human small intestine in vivo. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1117–1125. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90957-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruzdkov AA, Gromova LV. [Mechanisms of glucose absorption at a high carbohydrate level in the rat small intestine in vivo] (in Russian) Ross Fiziol Zh Im I M Sechenova. 2001;87:973–981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habold C, Foltzer-Jourdainne C, Le Maho Y, Lignot JH, Oudart H. Intestinal gluconeogenesis and glucose transport according to body fuel availability in rats. J Physiol. 2005;566:575–586. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.085217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell PA, Kellett GL. The active and passive components of glucose absorption in rat jejunum under low and high perfusion stress. J Physiol. 2002;544:579–589. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.028209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell PA, Richardson M, Affleck J, Kellett GL. Stimulation of fructose transport across the intestinal brush-border membrane by PMA is mediated by GLUT2 and dynamically regulated by protein kinase C. Biochem J. 2000;350:149–154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoenderop JG, Hartog A, Stuiver M, Doucet A, Willems PH, Bindels RJ. Localization of the epithelial Ca2+ channel in rabbit kidney and intestine. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:1171–1178. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1171171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Bhattacharjee A, Taylor JT, Zhang M, Keyser BM, Marrero L, Li M. [Ca2+]i regulates trafficking of Cav1.3 (α1D Ca2+ channel) in insulin-secreting cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C213–C221. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00346.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellett GL. The facilitated component of intestinal glucose absorption. J Physiol. 2001;531:585–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0585h.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellett GL, Brot-Laroche E. Apical GLUT2: a major pathway of intestinal sugar absorption. Diabetes. 2005;54:3056–3062. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellett GL, Helliwell PA. The diffusive component of intestinal glucose absorption is mediated by the glucose-induced recruitment of GLUT2 to the brush-border membrane. Biochem J. 2000;350:155–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane JS, Whang EE, Rigberg DA, Hines OJ, Kwan D, Zinner MJ, McFadden DW, Diamond J, Ashley SW. Paracellular glucose transport plays a minor role in the unanesthetized dog. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G789–G794. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.3.G789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madara JL, Pappenheimer JR. Structural basis for physiological regulation of paracellular pathways in intestinal epithelia. J Membr Biol. 1987;100:149–164. doi: 10.1007/BF02209147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooseker MS. Organization, chemistry, and assembly of the cytoskeletal apparatus of the intestinal brush border. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1985;1:209–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.01.110185.001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EL, Mace OJ, Affleck J, Kellett GL. Apical GLUT2 and Cav1.3: regulation of rat intestinal glucose and calcium absorption. J Physiol. 2007;580:593–604. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EL, Mace OJ, Helliwell PA, Affleck J, Kellett GL. A role for Cav1.3 in rat intestinal calcium absorption. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;312:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman DA, Atkins JM, Seelig LL, Jr, Gomez-Sanchez C, Krejs GJ. Water and electrolyte movement and mucosal morphology in the jejunum of patients with portal hypertension. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:707–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pansu D, Bellaton C, Roche C, Bronner F. Duodenal and ileal calcium absorption in the rat and effects of vitamin D. Am J Physiol. 1983;244:G695–G700. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1983.244.6.G695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappenheimer JR, Reiss KZ. Contribution of solvent drag through intercellular junctions to absorption of nutrients by the small intestine of the rat. J Membr Biol. 1987;100:123–136. doi: 10.1007/BF02209145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxon ML, Zhao X, Black JD. Activation of protein kinase C isozymes is associated with post-mitotic events in intestinal epithelial cells in situ. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:747–763. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.3.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RM, Furne JK, Levitt MD. Paracellular intestinal transport of six-carbon sugars is negligible in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1206–1213. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90580-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slepchenko BM, Bronner F. Modeling of transcellular Ca transport in rat duodenum points to coexistence of two mechanisms of apical entry. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C270–C281. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.1.C270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soergel KH. Showdown at the tight junction. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1247–1250. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90974-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JR. ‘Putting the squeeze’ on the tight junction: understanding cytoskeletal regulation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2000;11:301–308. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JR. Show me the pathway! Regulation of paracellular permeability by Na+-glucose cotransport. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2000b;41:265–281. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JR, Angle JM, Black ED, Joyal JL, Sacks DB, Madara JL. PKC-dependent regulation of transepithelial resistance: roles of MLC and MLC kinase. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C554–C562. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.3.C554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JR, Rill BK, Carlson SL, Carnes D, Kerner R, Mrsny RJ, Madara JL. Physiological regulation of epithelial tight junctions is associated with myosin light-chain phosphorylation. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1378–C1385. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhing MR, Kimura RE. The effect of surgical bowel manipulation and anesthesia on intestinal glucose absorption in rats. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2790–2798. doi: 10.1172/JCI117983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman RH, Fullmer CS. Vitamin D and intestinal calcium transport: facts, speculations and hypotheses. J Nutr. 1995;125:1971S–1979S. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.suppl_7.1971S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Lipscombe D. Neuronal Cav1.3α1 L-type channels activate at relatively hyperpolarized membrane potentials and are incompletely inhibited by dihydropyridines. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5944–5951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-05944.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younoszai MK, Nathan R. Intestinal calcium absorption is enhanced by d-glucose in diabetic and control rats. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:933–938. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(85)80010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang L, Peng JB, Tou L, Takanaga H, Adam RM, Hediger MA, Freeman MR. Calcium-selective ion channel, CaT1, is apically localized in gastrointestinal tract epithelia and is aberrantly expressed in human malignancies. Laboratory Invest. 2002;82:1755–1764. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000043910.41414.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]