Abstract

Whether the δ -opioid receptor (DOR) system can modulate behavioral effects of cocaine remains equivocal. We examined whether site- and subtype-selective blockade of DORs within the rat mesocorticolimbic system affects cocaine self-administration. The DOR antagonist naltrindole 5′-isothiocyanate (5′-NTII; 5 nmol) was microinjected into the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), ventral tegmental area (VTA), or amygdala (AMYG) in rats self-administering 1.5 mg/kg cocaine under a progressive ratio (PR)schedule. Intra-NAcc 5′-NTII significantly decreased cocaine self-administration, while 5′-NTII administration into the VTA significantly increased cocaine-maintained responding. 5′-NTII adminsitration into the AMYG produced no effect. These data support a site-specific role of DORs in cocaine's behavioral effects.

Whereas the initial sites of action governing cocaine reinforcement are thought to be dopamine (DA) transporters within the mesocorticolimbic system (see Koob et al.1998 for review), a number of other neurotransmitter systems co-localized within the mesocorticolimbic system can modulate the reinforcing effects of cocaine, including the endogenous opioid system. For example, non-selective opioid receptor blockade with naloxone or naltrexone can decrease cocaine self-administration in both non-human primates (Mello et al 1990) and rodents (Carroll et al 1986; De Vry et al 1989; Corrigall and Coen 1991; Ramsey and Van Ree 1991; Ramsey et al 1999). The relative contributions of μ, δ, and κ opioid receptor subtype-specific antagonism by these compounds on decreased cocaine self-administration remain equivocal. For example, our laboratory reported that site specific microinjections of the μ-opioid receptor (MOR) selective antagonist beta-funaltrexamine (β-FNA) attenuated responding for cocaine under a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement in rats (Ward et al 2003). However, MOR blockade has been shown by others to be ineffective in altering cocaine's reinforcing effects (Martin et al 1998; Corrigall et al 1999). Similarly, Kuzmin et al (1998) reported that κ-opioid antagonism decreased cocaine self-administration in rats, while others have reported no effect of κ-opioid antagonism on cocaine self-administration in rats (Glick et al 1995) and rhesus monkeys (Negus et al 1997).

Evidence also suggests that δ-opioid receptor (DOR) selective compounds and cocaine may interact with common neural substrates (Mansour et al 1987; Fowler et al 1989; Madras et al 1989; Kaufman et al 1991; Svingos et al 1999). For over a decade, researchers have been investigating whether selective DOR antagonism can attenuate the reinforcing effects of cocaine in laboratory animals, but results again are ambiguous. For example, Reid et al. (1995) demonstrated that i.p. administration of the DOR selective antagonist naltrindole decreased responding for cocaine in rats regardless of the schedule of reinforcement. Conversely, de Vries et al (1995) reported that only a high dose of naltrindole which also decreased locomotor activity (10 mg/kg i.p.) attenuated cocaine self-administration. In rhesus monkeys, i.v. naltrindole administration produced decreases in cocaine self-administration; however these effects were inconsistent across animals and sessions and were not dose-related (Negus et al 1995). The 5′-isothiocyanate analog of naltrindole, 5′-NTII, significantly decreased cocaine self-administration in rats when administered i.c.v, but this attenuation was also modest in comparison to the effect of i.c.v. 5′-NTII on heroin self-administration in the same study (Martin et al. 2000).

The present studies were performed to determine whether site-specific administration of 5′-NTII to brain regions within the mesocorticolimbic system alters motivation to self-administer cocaine under a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement in rats. 5′NTII is well suited for these self-administration studies because of its long duration of action; 5′-NTII has been shown to produce selective, insurmountable antagonism of DOR agonists in vitro and in vivo (Portoghese et al 1990). Interestingly, although 5′-NTII was synthesized to be a receptor-alkylating antagonist, it appears to act primarily by decreasing the affinity of the receptor for the agonist rather than by decreasing DOR density (Chakrabarti et al 1993). DORs have been located in the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), ventral tegmental area (VTA) and amygdala (AMYG) (Cahill et al 2001); therefore, we investigated the effect of bilateral microinjection of 5 nmol 5′-NTII into the NAcc, VTA, or AMYG, on cocaine self-administration maintained under a PR schedule of reinforcement.

Male Fischer 344 rats (n = 44; 275-300 g; Charles River, Raleigh, North Carolina) were used for the following experiments. Following arrival at the facility all rats were acclimated for a 2 week period and maintained on a reverse light/dark cycle (dark 3:00 AM-3:00 PM). The care and treatment of all animals was in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research (National Research Council 2003; http://nap.edu) and conformed to the standards of the Wake Forest University Animal Care and Use Committee and the National Institutes of Health. Food and water were available ad libitum throughout all phases of the experiment. Following acclimation, rats were implanted with intravenous cannulae into the right jugular vein under anesthesia as described previously (Ward et al 2003). Rats were individually housed and trained in 25-cm × 25-cm × 25-cm operant testing chambers containing a retractable lever and stimulus light mounted directly above the lever. A motor driven syringe pump was located in front of the chamber. The cannula was connected through a stainless steel protective spring to a counterbalanced swivel apparatus that allowed free movement within the operant chamber. Following recovery from jugular cannulation, animals were given access to a single response lever that controlled the delivery of 1.5 mg/kg/infusion cocaine (cocaine hydrochloride, RTI, Research Triangle Park, NC) over 3-5 seconds based on body weight under a fixed ratio (FR) 1 schedule. Concurrent with the start of each drug infusion, a stimulus light located above the lever was activated to signal a 20-s post-infusion time-out period, during which the lever was retracted and no response could be made. After establishing a stable daily pattern of cocaine intake (3 consecutive days of >30 injections/6 h and regular post-infusion pauses) on an FR1 schedule, rats were switched to a PR schedule of reinforcement. Under this schedule animals were required to make a progressively greater number of responses to obtain each subsequent infusion throughout the test session. Drug infusions were contingent upon completion of ratio requirements incremented through the following progression: 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 15, 20, 25, 32, 40, 50, 62, 77, 95, 118, 145, 178, 219, 268, 328, 402, 492, 603, etc. The final ratio completed before a 1-h time period elapsed with no responses was defined as the break point. After achieving three consecutive days of stable break points (break points stayed within a range of three increments with no upward or downward trends), animals were anesthetized and received bilateral microinjections of 5′-NTII (Research Biochemicals International, Natick, MA) or vehicle into the NAcc (n = 8/group), VTA (n = 8/group), or AMYG (n = 6/group).

5′-NTII (5 nmol) or vehicle was administered bilaterally in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to anesthetized rats (combination 75 mg/kg ketamine and 8 mg/kg xylazine) placed in a stereotaxic apparatus with the nose piece set at 2.5 mm below the horizontal. A micro-injector was attached to the arm of the stereotax via polyethylene tubing to a Hamilton gas-tight micro-syringe which was fitted into a syringe pump (Razel Scientific Instruments Inc., Stamford, CT). The micro-injector was lowered stereotaxically into the NAcc (+ 7.5 mm anterior to lambda, ± 1.5 mm lateral to the midline, and − 6.5 mm ventral to skull surface), VTA (+ 3.2 mm anterior to lambda, ± 1.0 mm lateral to the midline, and − 8.2 mm ventral to the skull surface) or AMYG (−2.8 posterior to bregma, ± 5.0 lateral to the midline, and −8.2 ventral to the skull surface). The total volume of injection was 1 μL (0.5 μL into each hemisphere) administered at a rate of 1 μL/min using the syringe pump, with flow of the proper injection volume confirmed by observing the movement of an air bubble for a pre-determined distance along the polyethylene tubing connecting the micro-syringe to the micro-injector. The micro-injector was left in place for 5 min to allow for pressure equilibration and then slowly withdrawn. The exterior incision was then sutured and dressed with antibiotic (Neosporin ointment; Pfizer, Inc. Consumer Healthcare, Morris Plains, NJ).

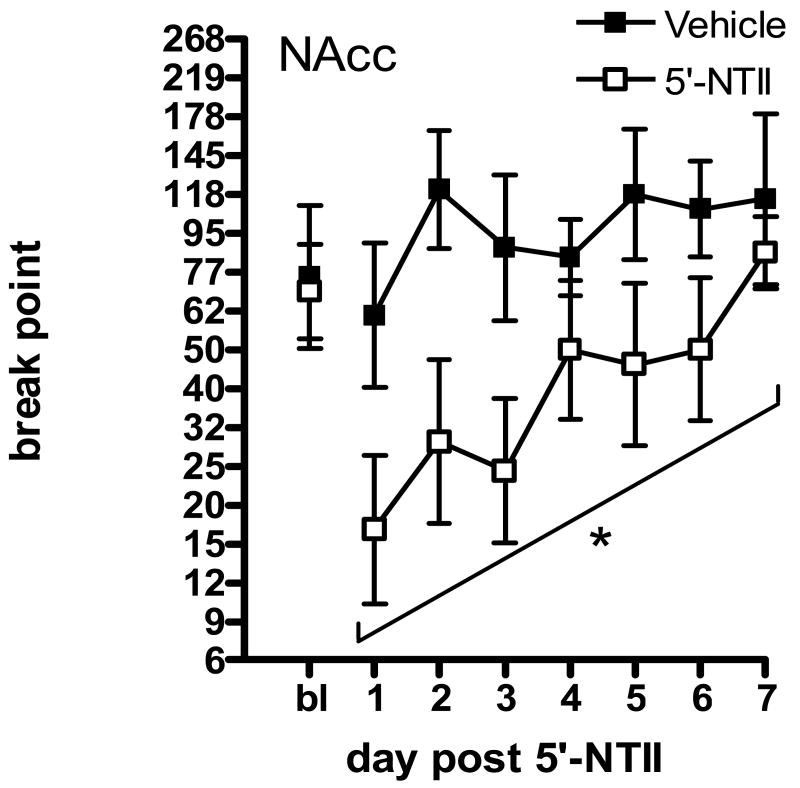

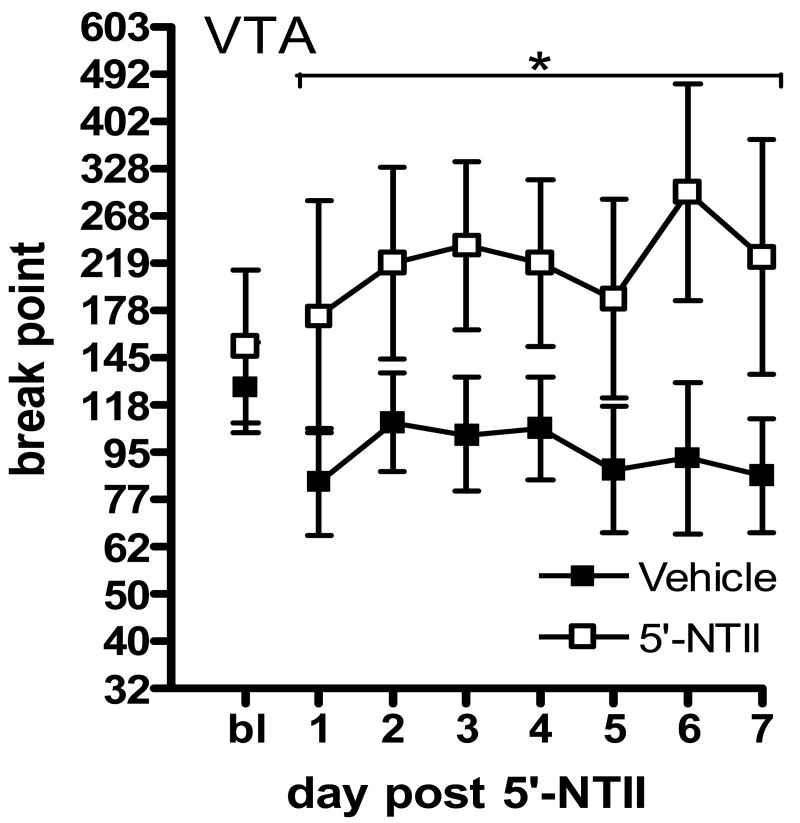

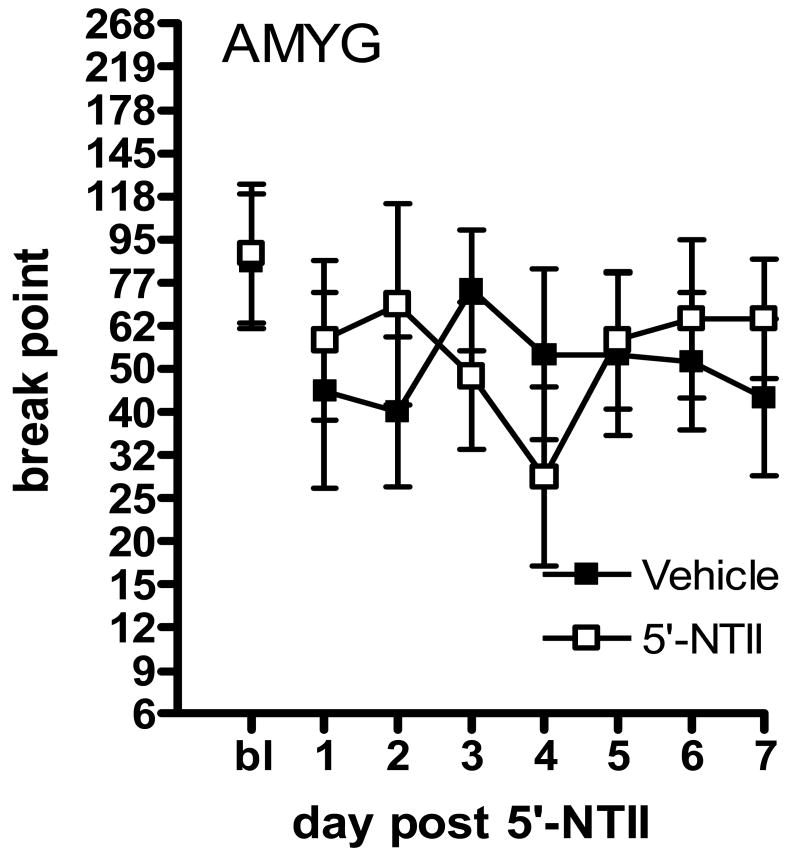

Animals were given one day of recovery following microinjection before being given access again to 1.5 mg/kg/infusion cocaine under the PR schedule. Break points were reassessed for 7 consecutive days. In order to conform to the requirement of homogeneity of variance for these statistical analyses, break points were log transformed; this conversion is equivalent to using the number of infusions self-administered during the session. Figure 1 illustrates that microinjection of 5′-NTII into the NAcc significantly decreased responding for cocaine under the PR schedule as compared to vehicle. Figure 1 illustrates the effect of 5′-NTII administration into the NAcc. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA; Prism4, GraphPad Software) revealed a significant main effect of treatment (F(1,112) = 19.51, p<0.01), with no significant effect of time (F(6,112) = 0.55, n.s.) and no interaction (F(6,112) = 1.67, n.s.). Bonferroni posttest analysis revealed no statistical differences in means at specific time points. Figure 2 illustrates the effect of 5′-NTII administration into the VTA. Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of treatment (F(1,112) = 18.52, p<0.01), with no significant effect of time (F(6,112) = 0.20, n.s.) and no interaction (F(6,112) < 1, n.s.). The high level of variability in cocaine-maintained responding following intra-VTA administration of 5′-NTII resulted from subjects' increased break points occurring at different time points across the retest period (see Table 1). Bonferroni posttest analysis revealed no statistical differences in means at specific time points. Figure 3 illustrates the effect of 5′-NTII administration into the AMYG. Two-way ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of treatment (F(1,70) = 0.08, n.s.) or time (F(6,70) =0.23, n.s.) and no interaction (F(6,70) = 0.58, n.s.).

Figure 1.

Effect of intra-NAcc 5′-NTII on responding for 1.5 mg/kg/infusion cocaine maintained under a PR schedule. Points represent the mean (±SEM) break point reached following microinjection of DMSO (■, n=8) or 5 nmol 5′-NTII (□, n=8) into the NAcc. Asterisk indicates significant difference from Vehicle (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Effect of intra-VTA 5′-NTII on responding for 1.5 mg/kg/infusion cocaine maintained under a PR schedule. Points represent the mean (±SEM) break point reached following microinjection of DMSO (■, n=8) or 5 nmol 5′-NTII (□, n=8) into the VTA. Asterisk indicates significant difference from Vehicle (P < 0.05).

Table 1. Increases in break points following intra-VTA 5′-NTII microinjection.

Bolded cells indicate day(s) on which highest break point was achieved.

| Retest day(s) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Baseline | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| S370 | 95 | 20 | 95 | 178 | 603 | 603 | 492 | 95 |

| S372 | 268 | 402 | 492 | 219 | 77 | 118 | 219 | 145 |

| S375 | 62 | 145 | 118 | 77 | 77 | 62 | 77 | 40 |

| S377 | 40 | 50 | 40 | 62 | 118 | 40 | 40 | 50 |

| S384 | 178 | 145 | 286 | 219 | 178 | 178 | 1646 | 1347 |

| S388 | 492 | 1646 | 1347 | 603 | 328 | 402 | 268 | 219 |

| S418 | 402 | 402 | 402 | 1102 | 1102 | 1102 | 1102 | 1102 |

| S419 | 118 | 118 | 145 | 145 | 178 | 95 | 328 | 603 |

Figure 3.

Effect of intra-AMYG 5′-NTII on responding for 1.5 mg/kg/infusion cocaine maintained under a PR schedule. Points represent the mean (±SEM) break point reached following microinjection of DMSO (■, n=6) or 5 nmol 5′-NTII (□, n=6) into the AMYG.

These results are the first to suggest site-specific effects of tonic inhibition of DORs in the rat brain by a long-lasting δ selective antagonist on the reinforcing effects of cocaine. Irreversible blockade of DORs within the NAcc decreased responding for cocaine below baseline levels as measured by the PR schedule of reinforcement. In contrast, administration of 5′-NTII into the VTA significantly increased cocaine-maintained responding under the PR schedule as compared to vehicle. Microinjection of 5′-NTII into the AMYG was without effect.

The NAcc data are consistent with previous reports that DOR antagonism can significantly attenuate responding for cocaine (Reid et al 1995), although this effect had been characterized as modest (Negus et al 1995; Martin et al 2000) and inconsistent (Negus et al 1995). The present findings are most similar to Martin et al (2000), who reported that i.c.v. administration of 40 nmol 5′-NTII decreased responding for cocaine maintained under an FR5 schedule. The time course of this effect paralleled the time course of intra-NAcc 5′-NTII, with responding for cocaine returning to baseline levels by the fourth retest day in both studies. While the present result does not provide information as to the neurobiology underlying the effect of intra-NAcc 5′-NTII on cocaine reinforcement, it suggests that endogenous activation of DORs within the NAcc during cocaine self-administration contributes to reinforcement mechanisms. Indeed, DOR activation and cocaine administration produce comparable effects, including hyper-locomotion (Kalivas et al 1983), positive reinforcement (Shippenberg et al 1987) and increases in extracellular DA its metabolites in the NAcc (Spanagel et al 1990; Longoni et al 1991; Manzanares et al 1993). Furthermore, immunohistochemical data reveal that DORs and DA transporters are co-localized within the NAcc in a way which indicates that DOR agonists can both directly and indirectly modulate extracellular dopamine levels (Svingos et al 1999). This suggests that increases in extracellular DA during cocaine self-administration may be further augmented by activation of DORs within the NAcc, and that intra-NAcc 5′-NTII may attenuate cocaine self-administration via inhibition of this facilitation.

While the present results suggest that blockade of DORs within the NAcc decrease cocaine's reinforcing effects, they also demonstrate that intra-VTA 5′-NTII increased responding for cocaine, suggesting that inactivation of DORs within the VTA enhanced the reinforcing effects of cocaine. This is somewhat surprising given that activation of DORs within the VTA produce cocaine-like effects similar to those reported when DOR agonists are administered into the NAcc. For example, intra-VTA administration of the DOR agonist DPDPE increases both DA and DOPAC levels in the NAcc (Devine et al 1993) and stimulates locomotor activity (Klitenick and Wirtshafter 1995). Interestingly, however, Ukai et al (1994) reported that while i.c.v. injection of the μ-selective agonist DAMGO inhibited cocaine-induced locomotor behavior, the δ-selective agonist DPLPE enhanced cocaine-induced locomotor activity. Furthermore, the locomotor-activating effects of cocaine are also enhanced in transgenic mice lacking the DOR (Chefer et al 2004). While the localization of DORs within the NAcc has been well characterized (Svingos et al 1999), less is known regarding the microstructural distribution of DORs within the VTA, as well as the chemical and anatomical profile of neurons containing these DORs (e.g. GABAergic or DAergic projection neurons). Preliminary evidence does suggest that these receptor subtypes within the VTA have distinct microstructural localization, in that both MORs and DORs have been located on neurons projecting to the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and that the DOR labeling pattern appears to be complementary to that of the MOR (Svingos et al 2001; Svingos personal communication). One early interpretation of the present data is that this enhanced response to cocaine following blockade of DORs is mediated by a disinhibition of projections from the VTA to the mPFC, a brain region implicated in the development of drug sensitization (see Steketee 2003 for review).

Microinjection of 5′-NTII into the AMYG did not affect motivation to self-administer cocaine under a PR schedule. The AMYG has been shown by others to play a weak role in cocaine self-administration maintained under a PR schedule (McGregor and Roberts 1993, 1994; but see Loh and Roberts 1990). Instead, a wealth of evidence demonstrates the importance of the AMYG specifically in cocaine-seeking behavior (Whitelaw et al 1996; Meil and See 1997; Kantak et al 2002; Yun and Fields 2003; see See 2005 for review).

In summary, the present results support the hypothesis that the DOR system can modulate the reinforcing effects of cocaine. The δ-opioid selective antagonist 5′-NTII decreased cocaine-maintained responding when microinjected in the NAcc but increased cocaine self-administration when administered into the VTA. Administration of 5′-NTII into the amygdala was without effect. These results support the hypothesis that the DOR system can site-specifically modulate the reinforcing effects of cocaine; however, the mechanism by which 5′-NTII differentially modulates cocaine's reinforcing effects within the NAcc versus VTA merits further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (RO1DA12498). The present experiments are in compliance with the current USA laws governing the care and use of laboratory mammals in behavioral research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Cahill CM, McClellan KA, Morinville A, Hoffert C, Hubatsch D, O'Donnell D, Beaudet A. Immunohistochemical distribution of delta opioid receptors in the rat central nervous system: Evidence for somatodendritic labeling and antigen-specific cellular compartmentalization. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2001;440(1):65–84. doi: 10.1002/cne.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carroll ME, Lac ST, Walker MJ, Kragh R, Newman T. Effects of naltrexone on intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats during food satiation and deprivation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1986;238(1):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chakrabarti S, Sultana M, Portoghese PS, Takemori AE. Differential antagonism by naltrindole-5′-isothiocyanate on [3H]DSLET and [3H]DPDPE binding to striatal slices of mice. Life Sci. 1993;53(23):1761–1765. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90163-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chefer VI, Kieffer BL, Shippenberg TS. Contrasting effects of mu opioid receptor and delta opioid receptor deletion upon the behavioral and neurochemical effects of cocaine. Neuroscience. 2004;127(2):497–503. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corrigall WA, Coen KM. Opiate antagonists reduce cocaine but not nicotine self-administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;104(2):167–170. doi: 10.1007/BF02244173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corrigall WA, Coen KM, Adamson KL, Chow BLC. The mu opioid agonist DAMGO alters the intravenous self-administration of cocaine in rats: mechanisms in the ventral tegmental area. Psychopharmacology. 1999;141(4):428–435. doi: 10.1007/s002130050853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Vries TJ, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Elmer G, Shippenberg TS. Lack of involvement of delta-opioid receptors in mediating the rewarding effects of cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;120(4):442–448. doi: 10.1007/BF02245816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Vry J, Donselaar I, Van Ree JM. Food deprivation and acquisition of intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats: effect of naltrexone and haloperidol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251(2):735–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devine DP, Leone P, Pocock D, Wise RA. Differential Involvement of Ventral Tegmental-Mu, Tegmental-Delta and Kappa-Opioid Receptors in Modulation of Basal Mesolimbic Dopamine Release - In-Vivo Microdialysis Studies. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1993;266(3):1236–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wolf AP, Dewey SL, Schlyer DJ, Macgregor RR, Hitzemann R, Logan J, Bendriem B, Gatley SJ. Mapping cocaine binding sites in human and baboon brain in vivo. Synapse. 1989;4(4):371–377. doi: 10.1002/syn.890040412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glick SD, Maisonneuve IM, Raucci J, Archer S. Kappa opioid inhibition of morphine and cocaine self-administration in rats. Brain Res. 1995;681(12):147–152. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00306-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalivas PW, Widerlov E, Stanley D, Breese G, Prange AJ., Jr Enkephalin action on the mesolimbic system: a dopamine-dependent and a dopamine-independent increase in locomotor activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1983;227(1):229–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kantak KM, Black Y, Valencia E, Green-Jordan K, Eichenbaum HB. Dissociable effects of lidocaine inactivation of the rostral and caudal basolateral amygdala on the maintenance and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. J Neurosci. 2002;22(3):1126–1136. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-01126.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufman MJ, Spealman RD, Madras BK. Distribution of cocaine recognition sites in monkey brain: I. In vitro autoradiography with [3H]CFT. Synapse. 1991;9(3):177–187. doi: 10.1002/syn.890090304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klitenick MA, Wirtshafter D. Behavioral and neurochemical effects of opioids in the paramedian midbrain tegmentum including the median raphe nucleus and ventral tegmental area. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273(1):327–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koob GF, Sanna PP, Bloom FE. Neuroscience of addiction. Neuron. 1998;21(3):467–476. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuzmin AV, Gerrits MAFM, Van Ree JM. kappa-opioid receptor blockade with nor-binaltorphimine modulates cocaine self-administration in drug-naive rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;358(3):197–202. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00637-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loh EA, Roberts DC. Break-points on a progressive ratio schedule reinforced by intravenous cocaine increase following depletion of forebrain serotonin. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1990;101(2):262–266. doi: 10.1007/BF02244137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Longoni R, Spina L, Mulas A, Carboni E, Garau L, Melchiorri P, Di Chiara G. (D-Ala2)deltorphin II: D1-dependent stereotypies and stimulation of dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 1991;11(6):1565–1576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01565.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madras BK, Spealman RD, Fahey MA, Neumeyer JL, Saha JK, Milius RA. Cocaine receptors labeled by [3H]2 beta-carbomethoxy-3 beta-(4-fluorophenyl)tropane. Mol Pharmacol. 1989;36(4):518–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansour A, Khachaturian H, Lewis ME, Akil H, Watson SJ. Autoradiographic differentiation of mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptors in the rat forebrain and midbrain. J Neurosci. 1987;7(8):2445–2464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manzanares J, Durham RA, Lookingland KJ, Moore KE. delta-Opioid receptor-mediated regulation of central dopaminergic neurons in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;249(1):107–112. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90668-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin TJ, DeMontis MG, Kim SA, Sizemore GM, Dworkin SI, Smith JE. Effects of beta-funaltrexamine on dose-effect curves for heroin self-administration in rats: comparison with alteration of [H-3]DAMGO binding to rat brain sections. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;52(2):135–147. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin TJ, Kim SA, Cannon DG, Sizemore GM, Bian D, Porreca F, Smith JE. Antagonism of delta(2)-opioid receptors by naltrindole-5 ′-isothiocyanate attenuates heroin self-administration but not antinociception in rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2000;294(3):975–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGregor A, Roberts DC. Dopaminergic antagonism within the nucleus accumbens or the amygdala produces differential effects on intravenous cocaine self-administration under fixed and progressive ratio schedules of reinforcement. Brain Res. 1993;624(12):245–252. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90084-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGregor A, Baker G, Roberts DCS. Effect of 6-Hydroxydopamine Lesions of the Amygdala on Intravenous Cocaine Self-Administration Under A Progressive Ratio Schedule of Reinforcement. Brain Research. 1994;646(2):273–278. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meil WM, See RE. Lesions of the basolateral amygdala abolish the ability of drug associated cues to reinstate responding during withdrawal from self-administered cocaine. Behavioural Brain Research. 1997;87(2):139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)02270-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Bree MP, Lukas SE. Buprenorphine and naltrexone effects on cocaine self-administration by rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;254(3):926–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Negus SS, Mello NK, Portoghese PS, Lukas SE, Mendelson JH. Role of delta opioid receptors in the reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273(3):1245–1256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Negus SS, Mello NK, Portoghese PS, Lin CE. Effects of kappa opioids on cocaine self-administration by rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282(1):44–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Portoghese PS, Sultana M, Takemori AE. Naltrindole 5′-isothiocyanate: a nonequilibrium, highly selective delta opioid receptor antagonist. J Med Chem. 1990 Jun;33(6):1547–8. doi: 10.1021/jm00168a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramsey NF, Van Ree JM. Intracerebroventricular naltrexone treatment attenuates acquisition of intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;40(4):807–810. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90090-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramsey NF, Gerrits MA, Van Ree JM. Naltrexone affects cocaine self-administration in naive rats through the ventral tegmental area rather than dopaminergic target regions. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;9(12):93–99. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(98)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reid LD, Glick SD, Menkens KA, French ED, Bilsky EJ, Porreca F. Cocaine Self-Administration and Naltrindole, A Delta-Selective Opioid Antagonist. Neuroreport. 1995;6(10):1409–1412. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199507100-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.See RE. Neural substrates of cocaine-cue associations that trigger relapse. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;526(13):140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shippenberg TS, Bals-Kubik R, Herz A. Motivational properties of opioids: evidence that an activation of delta-receptors mediates reinforcement processes. Brain Res. 1987;436(2):234–239. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91667-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spanagel R, Herz A, Shippenberg TS. The effects of opioid peptides on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens: an in vivo microdialysis study. J Neurochem. 1990;55(5):1734–1740. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steketee JD. Neurotransmitter systems of the medial prefrontal cortex: potential role in sensitization to psychostimulants. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;41(23):203–228. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Svingos AL, Clarke CL, Pickel VM. Localization of the delta-opioid receptor and dopamine transporter in the nucleus accumbens shell: implications for opiate and psychostimulant cross-sensitization. Synapse. 1999;34(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199910)34:1<1::AID-SYN1>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Svingos AL, Garzon M, Colago EE, Pickel VM. Mu-opioid receptors in the ventral tegmental area are targeted to presynaptically and directly modulate mesocortical projection neurons. Synapse. 2001;41(3):221–229. doi: 10.1002/syn.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ukai M, Mizutani M, Kameyama T. Opioid peptides selective for receptor types modulate cocaine-induced behavioral responses in mice. Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi. 1994;14(3):153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ward SJ, Martin TJ, Roberts DCS. Beta-funaltrexamine affects cocaine self-administration in rats responding on a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2003;75(2):301–307. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whitelaw RB, Markou A, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Excitotoxic lesions of the basolateral amygdala impair the acquisition of cocaine-seeking behaviour under a second-order schedule of reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;127(3):213–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yun IA, Fields HL. Basolateral amygdala lesions impair both cue- and cocaine-induced reinstatement in animals trained on a discriminative stimulus task. Neuroscience. 2003;121(3):747–757. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]