Abstract

The subject of collective attention is central to an information age where millions of people are inundated with daily messages. It is thus of interest to understand how attention to novel items propagates and eventually fades among large populations. We have analyzed the dynamics of collective attention among 1 million users of an interactive web site, digg.com, devoted to thousands of novel news stories. The observations can be described by a dynamical model characterized by a single novelty factor. Our measurements indicate that novelty within groups decays with a stretched-exponential law, suggesting the existence of a natural time scale over which attention fades.

Keywords: economics of attention, information access

The problem of collective attention is at the heart of decision making and the spread of ideas, and, as such, it has been studied at the individual and small group level by a number of psychologists (1, 2), economists,† and researchers in the area of marketing and advertising (3–5). Attention also affects the propagation of information in social networks, determining the effectiveness of advertising and viral marketing.‡ And although progress on this problem has been made in small laboratory studies and in the theoretical literature of attention economics (6), it is still lacking empirical results from very large groups in a natural, nonlaboratory, setting.

To understand the process underlying attention in large groups, consider as an example how a news story spreads among a group of people. When it first comes out, the story catches the attention of a few, who may further pass it on to others if they find it interesting enough. If a lot of people start to pay attention to this story, its exposure in the media will continue to increase. In other words, a positive-reinforcement effect sets in such that the more popular the story becomes, the faster it spreads.

This growth is counterbalanced by the fact that the novelty of a story tends to fade with time and thus the attention that people pay to it. This can be due either to habituation or competition from other new stories, which is the regime recently studied by Falkinger (6). Therefore, in considering the dynamics of collective attention, two competing effects are present: the growth in the number of people that attend to a given story and the habituation or competition from other stories that makes the same story less likely to be attractive as time goes on. This process becomes more complex in the realistic case of multiple items or stories appearing at the same time, because now people also have the choice of which stories to focus on with their limited attention.

To study the dynamics of collective attention and its relation to novel inputs in a natural setting, we analyzed the behavioral patterns of 1 million people interacting with a news web site whose content is solely determined by its own users. Because people using this web site assign each news story an explicit measure of popularity, we were able to determine the growth and decay of attention for thousands of news stories and to validate a theoretical model that predicts both the dynamics and the statistical distribution of story lifetimes.

The web site under study, digg.com, is a digital media democracy that allows its users to submit news stories they discover from the internet.§ A new submission immediately appears on a repository web page called “Upcoming Stories,” where other members can find the story and, if they like it, add a “digg” to it. A so-called digg number is shown next to each story's headline, which simply counts how many users have digged the story in the past.¶ If a submission fails to receive enough diggs within a certain time limit, it eventually falls out of the “Upcoming” section, but if it does earn a critical mass of diggs quickly enough, it becomes popular and jumps to the digg.com front page.‖ Because the front page can display only a limited number of stories, old stories eventually get replaced by newer stories as the page gets constantly updated. If a story becomes very popular, however, it qualifies as a “Top 10” and stays on the right side of the front page for a very long time.

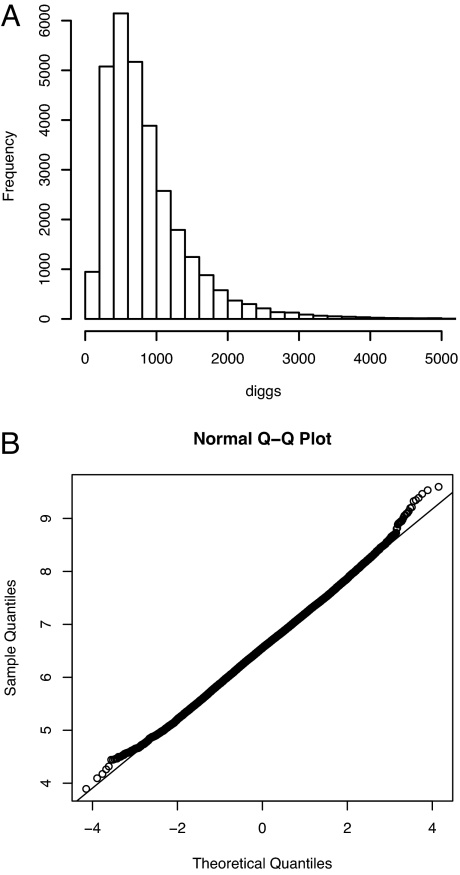

When a story first appears on the front page it attracts much attention, causing its digg number, Nt, to build up quickly. After a couple of hours, its digg rate slows down because of both its lack of novelty and its lack of prominent visibility (reflected in the fact that it moves away from the front page). Thus, the digg number of each story eventually saturates to a value N∞ that depends on both its popularity growth and its novelty decay. To determine the statistical distribution of this saturation number, which corresponds to the number of diggs it has accumulated throughout its evolution, we measured the histogram of the final diggs of all 29,864 popular stories in the year 2006. As can be seen from Fig. 1, the distribution appears to be quite skewed, with the normal Q–Q plot of log(N∞) a straight line. A Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test of log(N∞) with mean 6.546 and standard deviation 0.6626 yields a P value of 0.0939, suggesting that N∞ follows a log-normal distribution.

Fig. 1.

Frequency and distribution of diggs. (A) The histogram of the 29,684 diggs in 2006, as of January 9, 2007. (B) The normal Q–Q plot of log(N∞). The straight line shows that log(N∞) follows a normal distribution with a slightly longer tail. This is due to digg.com's built-in reinforcement mechanism that favors those “top stories” that can stay on the front page and can be found at many other places (e.g., “popular stories in 30 days” and “popular stories in 365 days”).

It is then natural to ask whether Nt, the number of diggs of a popular story after finite time t, also follows a log-normal distribution. To answer this question, we tracked the digg numbers of 1,110 stories in January 2006 minute by minute. The distribution of log(Nt) again obeys a bell-shaped curve. As an example, a Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test of log(N2h) with mean 5.925 and standard deviation 0.5451 yields a P value as high as 0.5605, supporting the hypothesis that Nt also follows a log-normal distribution. The log-normal distribution can be explained by a simple stochastic dynamical model, which we now describe. If Nt represents the number of people who know the story at time t, in the absence of any habituation, on average, a fraction μ of those people will further spread the story to some of their friends. Mathematically, this assumption can be expressed as Nt = (1 + Xt)Nt−1, where X1, X2, … are positive, independent, and identically distributed random variables with mean μ and variance σ2. The requirement that Xi must be positive ensures that Nt can only grow with time. As we have discussed above, this growth in time is eventually curtailed by a decay in novelty, which we parameterize by a time-dependent factor rt, consisting of a series of decreasing positive numbers with the property that r1 = 1 and rt ↓ 0 as t ↑ ∞. With this additional parameter, the full stochastic dynamics of story propagation is governed by Nt = (1 + rtXt)Nt−1, where the factor rtXt acts as a discounted random multiplicative factor. When Xt is small (which is the case for small time steps), we have the following approximate solution:

|

where N0 is the initial population that is aware of the story. Taking logarithm of both sides, we obtain

|

The right hand side is a discounted sum of random variables, which for rt near 1 (small time steps), can be shown to be described by a normal distribution (7). It then follows that for large t, the probability distribution of Nt will be approximately log-normal.

Our dynamic model can be further tested by taking the mean and variance of both sides of Eq. 1:

|

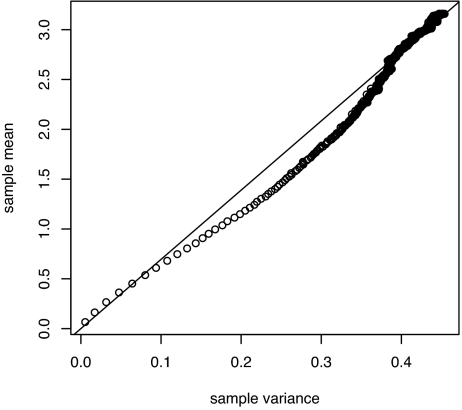

Hence, if our model is correct, a plot of the sample mean of log(Nt) − log(N0) versus the sample variance for each time t should yield a straight line passing through the origin with slope μ/σ2. One such plot for 1,110 stories collected in January 2007 is shown in Fig. 2. As can be seen, the points indeed lie on a line with slope 6.9. Although the fit is not perfect, it is indicative of a straight correlation between mean and variance.

Fig. 2.

Sample mean of log Nt − log N0 versus sample variance, for 1,110 stories in January 2007. Time unit is 1 minute. The points are plotted as follows. For each story, we calculate the quantity log Nt − log N0, which is the logarithm of its digg number measured t minutes after its first appearance on the front page, minus the logarithm of its initial digg number. We collect 1,110 such quantities for 1,110 stories. Then we compute their sample mean y and sample variance x, and mark the point (x,y). This is for one t. We repeat the process for t = 1,2,…, 1,440 and plot 1,440 points in total (i.e., 24 h). They lie roughly on a straight line passing through the origin with slope 6.9.

The decay factor rt can now be computed explicitly from Nt up to a constant scale. By taking expectation values of Eq. 2 and normalizing r1 to 1, we have

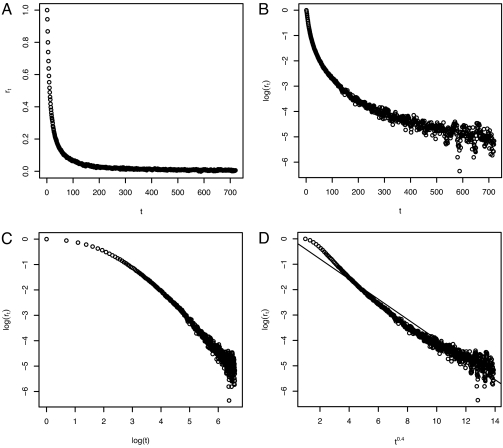

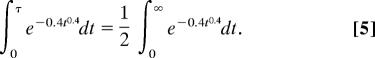

The curve of rt estimated from the 1,110 stories in January 2007 is shown in Fig. 3a. As can be seen, rt decays very fast in the first 2–2 hours, and its value becomes <0.03 after 3 hours. Fig. 3 b and c shows that rt decays slower than exponential and faster than power law. Fig. 3d shows that rt can be fit empirically to a stretched exponential relaxation or Kohlrausch–Williams–Watts law (8): rt ∼ e−0.4t0.4. The half-life τ of rt can then be determined by solving the equation

|

A numerical calculation gives τ = 69 minutes, or ≈1 hour. This characteristic time is consistent with the fact that a story usually lives on the front page for a period between 1 and 2 hours.

Fig. 3.

Decay factor curves. (A) The decay factor rt as a function of time. Time t is measured in minutes. (B) Log(rt) versus t. rt decays slower than exponential. (C) Log(rt) versus t. rt decays faster than power law. (D) Log(rt) versus t0.4. The slope is ≈−0.4.

The stretched exponential relaxation often occurs as the result of multiple characteristic relaxation time scales (8, 9). This is consistent with the fact that the decay rate of a story on digg.com depends on many factors, such as the story's topic category and the time of a day when it appears on the front page. The measured decay factor rt is thus an average of these various rates and describes the collective decay of attention.

These measurements, comprising the dynamics of 1 million users attending to thousands of novel stories, allowed us to determine the effect of novelty on the collective attention of very large groups of individuals, nicely isolating both the speed of propagation of new stories and their decay. We also showed that the growth and decay of collective attention can be described by a dynamical model characterized by a single novelty factor that determines the natural time scale over which attention fades. The exact value of the decay constant depends on the nature of the medium, but its functional form is universal in the sense that it fits many other phenomena characterized by many time scales (9). These results are applicable to a number of situations, such as the choice of which items to display in several kinds of news media, advertising, and any other medium that relies on a social network to spread its content.

Finally, we point out that these experiments, which complement large social network studies of viral marketing‡ are facilitated by the availability of web sites that attract millions of users, a fact that turns the internet into an interesting natural laboratory for testing and discovering the behavioral patterns of large populations on a very large scale (10).

Acknowledgments

We thank Xue Liu for many useful discussions.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Camerer, C. (2003) The Behavioral Challenge to Economics: Understanding Normal People. Paper presented at Federal Reserve of Boston meeting (2003).

Lefkovic, J., Adamic, L., Huberman, B. A. (2006) The Dynamics of Viral Marketing, Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Electronic Commerce (Assoc for Computing Machinery).

How Digg Works, http://www.digg.com/how.

In fact, digg users are given the option to “bury” a story, which will decrease the story's digg number. Because this rarely happens because of the nature of the interface (there is no obvious button to decrease the number of diggs), we ignore this possibility and simply assume that a story's digg number can only grow with time.

The actual machine-learning algorithm used to determine whether a story qualifies to appear on the front page is very complex and will not be discussed in this paper. This algorithm is stated to take into account possible manipulation of digg numbers.

References

- 1.Kahneman D. Attention and Effort. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pashler HE. The Psychology of Attention. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pieters FGM, Rosbergen E, Wedel M. J Marketing Res. 1999;36:424–438. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dukas R. Brain Behav Evol. 2004;63:197–210. doi: 10.1159/000076781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reis RI. J Monetary Econ. 2006;53:1761–1800. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falkinger J. J Econ Theory. 2007;133:266–294. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Embrechts P, Maejima M. Probability Theory Relat Fields. 1984;68:2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindsey CP, Patterson GD. J Chem Phys. 1980;73:7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frisch U, Sornette D. J Phys I France. 1997;7:1155–1171. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watts D. Nature. 2007;445:489. doi: 10.1038/445489a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]