Abstract

Upon wounding or infection, a serine proteinase cascade in insect hemolymph leads to prophenoloxidase (proPO) activation and melanization, a defense response against invading microbes. In the tobacco hornworm Manduca sexta, this response is initiated via hemolymph proteinase 14 (HP14), a mosaic protein that interacts with bacterial peptidoglycan or fungal β-1,3-glucan to autoactivate. In this paper, we report the expression, purification, and functional analysis of M. sexta HP21 precursor, an HP14 substrate similar to Drosophila Snake. The recombinant proHP21 is a 51.1 kDa glycoprotein with an amino-terminal clip domain, a linker region, and a carboxyl-terminal serine proteinase domain. HP14, generated by incubating proHP14 with β-1,3-glucan and β-1,3-glucan recognition protein-2, activated proHP21 by limited proteolysis between Leu152 and Ile153. Active HP21 formed an SDS-stable complex with M. sexta serpin-4, a physiological regulator of the proPO activation system. We determined the P1 site of serpin-4 to be Arg355 and, thus, confirmed our prediction that HP21 has trypsin-like specificity. After active HP21 was added to the plasma, there was a major increase in PO activity. HP21 cleaved proPO activating proteinase-2 precursor (proPAP-2) after Lys153 and generated an amidase activity which activated proPO in the presence of serine proteinase homolog-1 and 2. In summary, we have discovered and reconstituted a branch of the proPO activation cascade in vitro: β-1,3-glucan recognition – proHP14 autoactivation – proHP21 cleavage – PAP-2 generation – proPO activation – melanin formation.

Keywords: Clip domain, Insect immunity, Melanization, Phenoloxidase, Proteinase cascade

1. Introduction

Insects can rapidly set off a battery of defense reactions to heal wounds and eliminate microbes (Gillespie et al., 1997; Hoffmann, 2003; Lavine and Strand, 2002). The fate of invading pathogens or parasites is largely governed by the acute-phase responses including phagocytosis, encapsulation, melanization, generation of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species, and synthesis of antimicrobial proteins. Examinations of the insect immune responses not only provide insights on the evolution of vertebrate innate immune systems, but also render it possible to block pathogen transmission in insect vectors of human diseases. One insect defense response under active investigation is the proteolytic activation of prophenoloxidase (proPO), a resistance mechanism against malaria parasites (Collins et al., 1986; Nappi and Christensen, 2005).

In insects and crustaceans, limited proteolysis generates active phenoloxidase (PO) which catalyzes the formation of quinones (Ashida and Brey, 1998; Nappi and Vass, 2001; Jiang and Kanost, 2000). Quinones are utilized in encapsulating parasites with a melanin sheath. Activation of proPO is mediated by a serine proteinase pathway triggered by the recognition of pathogen surface determinants (e.g. peptidoglycans and lipopolysaccharides of bacteria and glucans from fungi) (Kanost et al., 2004). According to the current model, these pathogen-associated molecular patterns interact with specific pattern recognition receptors in hemolymph and induce conformational changes required for association and self-activation of an initiation serine proteinase. The enzyme, through sequentially activated serine proteinases, eventually yields a specific proteinase to cleave proPO. At least in some insects, proPO activating proteinases (PAPs) require one or two non-catalytic serine proteinase homologs (SPHs) as a “cofactor” to generate active PO (Jiang et al., 1998; Lee et al., 1998; Kwon et al., 2000; Yu et al., 2003). Like PAPs, SPHs need cleavage activation by a serine proteinase in the cascade (Kim et al., 2002).

Until recently, little was known about the initiation proteinase of proPO activation pathway in arthropods. We reported the molecular cloning and functional analysis of M. sexta HP14, a modular serine proteinase containing seven disulfide knotted structures and one catalytic domain (Ji et al., 2004). The recombinant HP14 precursor binds to peptidoglycan, autoactivates, and triggers the proPO activation cascade. Additionally, β-1,3-glucan and M. sexta β-1,3-glucan recognition protein-2 (βGRP2) interact with proHP14 from the hemolymph, cause it to activate by autoproteolysis between Leu152 and Ile153, and initiate the pathway (Wang and Jiang, 2006). We have identified over 25 serine proteinases in the hemolymph of M. sexta larvae and suggested that some of these enzymes are members of the proPO activation cascade or other immune proteinase pathways (Jiang et al., 2005). HP21 and five other HPs have a predicted cleavage activation site between Leu and Ile/Val. Based on the functional study of M. sexta serpin-4 and -5, we proposed a branched pathway for proPO activation in the tobacco hornworm (Tong et al., 2005). This pathway is composed of HP14, HP21, and HPs activated by cutting after a Lys, Arg or His. Until now, direct experimental evidence on the connectivity of the pathway components has been lacking. Guided by HP21′s possible association with proPO activation and putative activation site, we examined and confirmed proHP21 as a protein substrate of HP14 and found cleaved HP21 activates proPAP-2. In the presence of M. sexta SPH-1 and SPH-2, PAP-2 generated active PO.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Insect rearing, bacterial challenge, and plasma collection

M. sexta eggs were purchased from Carolina Biological Supplies, and the larvae were reared on an artificial diet (Dunn and Drake, 1983). Day 2, 5th instar larvae were injected with Micrococcus luteus (50 μg/larva, 50 μl) (Sigma), formalin-killed Escherichia coli (108 cells/larva, 50 μl), or H2O (50 μl). Hemolymph samples collected from cut prolegs of the larvae at 24 h after injection were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 5 min to remove hemocytes.

2.2. Protein preparation and curdlan treatment

M. sexta βGRP2 (Jiang et al., 2004), proHP14 (Wang and Jiang, 2006), proPO (Jiang et al., 1997), and SPHs (Wang and Jiang, 2004) were purified from the larval plasma as previously reported. Recombinant serpin-4 (Tong et al., 2005) and proPAP-2 (Ji et al., 2003) were isolated from baculovirus-infected insect cell culture media. Curdlan from Alcaligenes faecalis (Sigma) was incubated with 0.3 N NaOH at room temperature for 10 min and then neutralized in 0.3 N HCl for another 10 min. After washing with H2O for 3 times, the treated curdlan was resuspended in H2O at 10 mg/ml and stored at 4°C.

2.3. Cloning, expression, and purification of M. sexta proHP21 from insect cells

For expressing HP21 zymogen, a recombinant baculovirus was constructed using the Bac-to-Bac system (Invitrogen). The proHP21 cDNA was amplified by PCR using Advantage cDNA Polymerase Mixture (BD Biosciences). Primers j539 (5′-AGAGGATCCGTAGATAAAATGC) and j540 (5′-AGTCTCGAGAGGCCACACGAC) correspond to nucleotides 63-83 and 1308-1328 (reverse complement) of the cDNA, respectively. The PCR product digested with BamHI and XhoI was separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the DNA fragment was recovered from the gel and inserted to the same sites in the vector pFH6 (Ji et al., 2003). The resulting plasmid (proHP21/pFH6), after sequence verification, was used to generate recombinant baculovirus for producing proHP21. Spodoptera frugiperda Sf9 cells (2×106 cells/ml) in 40 ml Sf900II serum-free medium were infected with the recombinant virus at a multiplicity of infection of 10 and grown at 27°C for 72 h with agitation at 100 rpm. The recombinant proHP21 in the conditioned medium was enriched by ion-exchange chromatography on a Q-Sepharose column. First of all, pH of the cell culture supernatant (40 ml) was adjusted to 8.3 with an equal volume of 40 mM NaOH containing 2 mM benzamidine. Flocculent substances were removed by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 10 min. The supernatant (80 ml) was incubated with 4.0 ml Q-Sepharose (Sigma) on ice for 30 min. The suspension was packed into a column, and the resin was washed with 40 ml buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 0.01% Tween-20, 1 mM benzamidine). The captured proteins were then eluted with 20 ml buffer A containing 0.5 M NaCl. To purify proHP21 by affinity chromatography, the elution fractions were pooled and incubated with 0.5 ml nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Qiagen) for 1 h with gentle agitation. The suspension was loaded into a column, and the resin was washed with buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 0.01% Tween-20). The bound proHP21 was eluted with 10 ml buffer B containing 250 mM imidazole and stored at -20°C.

2.4. Characterization of M. sexta proHP21

MALDI Mass Spectrometry was performed at Oklahoma State University Recombinant DNA/Protein Resource Facility on a Voyager Elite mass spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer). The purified proHP21 (400 ng) was mixed with an equal volume of saturated sinapinic acid matrix on a MALDI plate, air dried, and subjected to mass determination with delayed extraction. The spectra were calibrated using bovine serum albumin as an external standard. Isoelectric focusing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of proHP21 and isoelectric point standards (Bio-Rad) was performed on a precast PhastGel IEF3-9 (GM Health Care) according to the manufacturer′s instructions. To detect N-linked glycosylation, proHP21 (30 ng) was treated with 1×glycoprotein denaturing buffer (Sigma) at 100°C for 10 min. After adding one-tenth volume each of 10×G7 buffer and 10% Nonidet P-40, the protein samples were incubated with 2.5 μl PNGase F (Sigma) at 37°C for 1 h. To detect O-linked glycosylation, proHP21 (30 ng) was reacted with 2 μl O-glycosidase (Sigma) in 1×reaction buffer at 37°C for 3 h. These samples, as well as untreated proHP21 control, were heated at 95°C for 5 min in the presence of 1×SDS sample buffer containing 100 mM dithiothreitol and separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Immunoblot analysis was performed using 1:2,000 diluted HP21 antiserum as the 1st antibody.

2.5. Proteolytic activation of proHP21 by HP14

ProHP21 was incubated with proHP14, curdlan, βGRP2, and buffer C (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) at 37°C for 1 h. In the controls, proHP21, proHP14, or curdlan-βGRP2 was replaced by equal volume of buffer C. After separation by SDS-PAGE under reducing condition, half of the gel was visualized by silver staining, and the other half by immunoblot analysis. Specific proteolysis was revealed by changes in gel mobility of the zymogens and by differences between the test and controls. Peptide mass fingerprint analysis of the cleaved HP21 (1 μg) was carried out at Nevada Proteomics Center as previously described (Wang and Jiang, 2006). To detect HP21 amidase activity, aliquots of the reaction mixture and controls were incubated with 100 μM Gly-Arg-p-nitroanilide, Gly-Gly-Arg-p-nitroanilide, Gly-Ala-Arg-p-nitroanilide, Val-Gly-Arg-p-nitroanilide, Phe-Pro-Arg-p-nitroanilide, Phe-Val-Arg-p-nitroanilide, Ile-Glu-Gly-Arg-p-nitroanilide or Ile-Glu-Ala-Arg-p-nitroanilide (IEARpNA) in a microplate assay (24). One unit of activity is defined as ΔA405/min = 0.001.

2.6. Determination of the amino-terminal sequence and proteolytic cleavage site in HP21

HP21 (1 μg), generated by HP14 in the presence of curdlan and βGRP2, was resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad). After staining with Amino Black, the bands corresponding to the cleaved HP21 were subjected to automated Edman degradation at Nevada Proteomics Center. The cleavage site in HP21-activated PAP-2 was determined similarly.

2.7. Inhibitory regulation of HP21 by M. sexta serpin-4

To detect the enzyme-inhibitor complex, M. sexta serpin-4 was included in the reaction mixture containing proHP14, proHP21, curdlan, βGRP2, and buffer C. In the controls, proHP14, proHP21, or serpin-4 was replaced with an equal volume of the buffer. Following incubation at 37°C for 1 h, the reaction mixture and negative controls were separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE under reducing condition. Immunoblot analyses were performed using 1:2,000 diluted serpin-4 or HP21 antiserum as the first antibody. To determine the cleavage site in serpin-4, purified proHP14 (80 ng, 4 μl), proHP21 (80 ng, 4 μl), curdlan (20 μg, 2 μl), βGRP2 (80 ng, 4 μl), serpin-4 (0.4 μg, 4 μl), and buffer C (30 μl) were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. In one negative control, serpin-4 was substituted with 4 μl of buffer C whereas, in the other control, serpin-4 was incubated with 44 μl buffer C. After centrifugation, supernatants of the samples were subjected to MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Jiang et al., 2003b). The molecular mass of a major peak absent in the control spectra was compared with calculated masses of carboxyl-terminal peptides of M. sexta serpin-4 to deduce the position of cleavage.

2.8. Activation of proPO in the larval hemolymph by HP21

ProHP21 was preincubated with proHP14, curdlan, and βGRP2 at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction mixtures lacking proHP14, proHP21, or both were used as negative controls. Following centrifugation, the supernatants were incubated on ice with an equal volume of plasma from the naïve or bacteria-challenged larvae. After 30 min, PO activity in the reaction mixtures was assayed using dopamine as a substrate (Jiang et al., 2003a). To exclude the possibility that proHP21 or proHP14 directly activates proPO, the plasma was incubated with one of the proteinase zymogens at room temperature for 15 min prior to PO activity measurement.

2.9. Cleavage activation of proPAP-2 and proPO

To test whether or not HP21 activates proPAP-2, curdlan, βGRP2, proHP14, proHP21, and proPAP-2 were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction mixtures without proHP14, proHP21, or both were included as negative controls. After separation by SDS-PAGE, these samples were visualized by silver staining or immunoblot analysis using PAP-2 antibodies. To detect the amidase activity of PAP-2, the reaction mixture and negative controls were assayed using IEARpNA. The activation of proPO by HP21-generated PAP-2 was tested similarly. At first, curdlan, βGRP2, proHP14, proHP21 and proPAP-2 were preincubated at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction mixture without proPAP-2 was used as a negative control. After centrifugation, the supernatants were incubated with proPO, SPHs, and buffer C on ice for 40 min prior to PO activity assay.

3. Results

3.1. Structural features of HP21

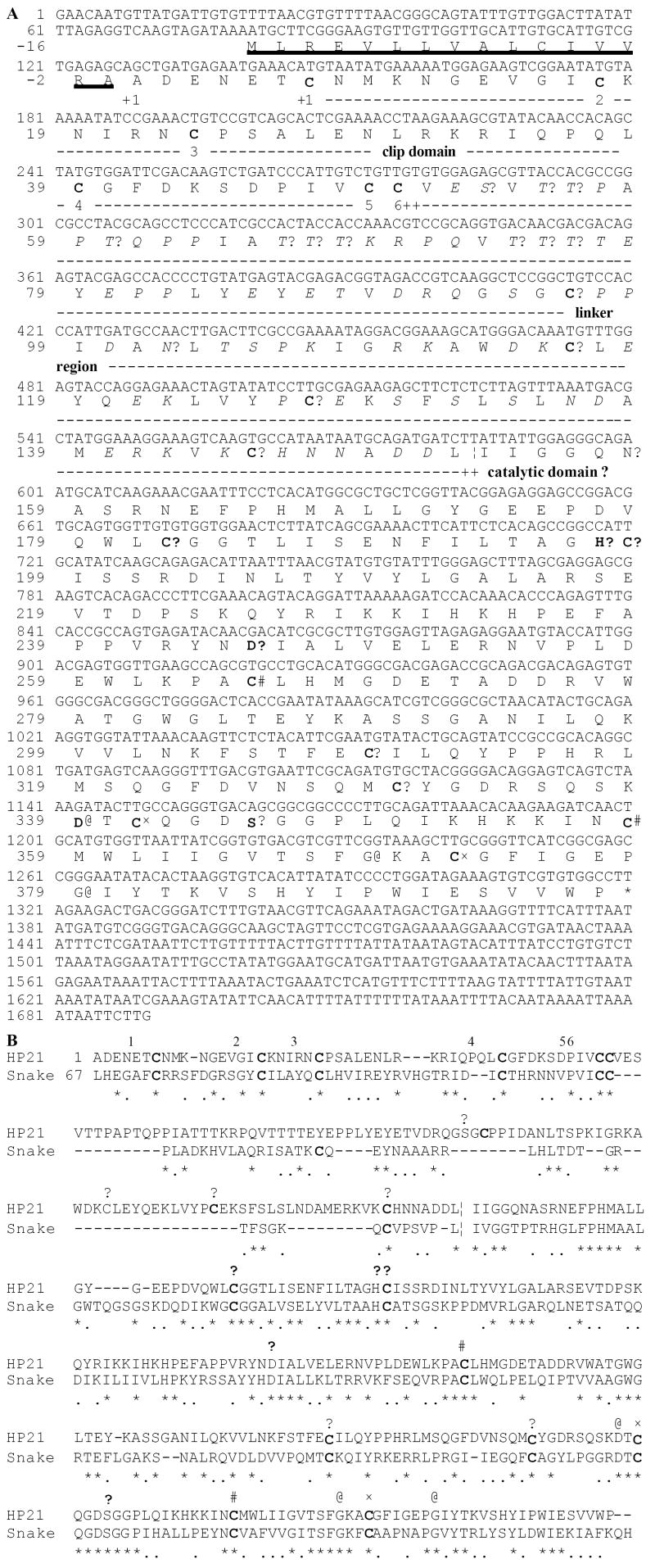

The 1,690 bp cDNA clone, isolated from the induced M. sexta fat body cDNA library, contains a complete open reading frame spanning nucleotides 81-1319 (Fig. 1A). The encoded protein (397 residues long) includes a 16-residue signal peptide for secretion, followed by a regulatory clip domain. The mature protein has a calculated molecular mass of 44,430 Da. Potential N- and O-linked glycosylation sites are present in the following sequences: Asn4-Glu-Thr, Asn102-Leu-Thr, Asn158-Ala-Ser, Asn205-Leu-Thr, Ser53 and Thr55, 56, 60, 66-68, 74-76. Most of these sites reside in the linker region (residues 51-152) between the clip and catalytic domains. In addition to Thr and Ser residues, Pro, Gln, Asn and charged residues are abundant in this region, which is likely exposed to aqueous solution. The putative activation cleavage site is between L152 and I153, indicative of an activating proteinase with chymotrypsin-like specificity. The catalytic domain of M. sexta HP21 is similar in sequence to S1 family of serine proteinases, including the catalytic triad of His197, Asp245 and Ser345. The primary substrate-specificity pocket is composed of Asp339, Gly369 and Gly379, suggesting that HP21 has a specificity for cleavage after positively charged residues (Perona and Craik, 1995).

Figure 1. Sequence, domain structure, and predicted disulfide linkage pattern of M. sexta HP21.

(A) cDNA and deduced amino acid sequences. Residues, shown in one-letter abbreviations, are aligned with the first nucleotide of each codon. The signal peptide is double underlined. Ser, Thr, Pro, Gln, Asn, Glu, Asp, Arg, Lys, and His residues in the linker sequence are in italics. Putative N- and O-linked glycosylation sites are denoted with “♦”. The stop codon is marked by an asterisk. (B) Sequence comparison with D. melanogaster Snake (Leu67 to His415). Identical (*) and similar (.) residues are indicated underneath the sequences. The twelve conserved Cys residues (marked 1~6, ■, ●, and ×) are presumably connected by disulfide bonds between 1-5, 2-4, 3-6 in the clip domain and between ■-■, ●-●, ×-× in the catalytic domains. While Cys145 and Cys265 (both marked “#”) may form an interchain disulfide bond, one of Cys96, Cys116 and Cys127 is predicted to form another interchain bond with Cys358 (Jiang and Kanost, 2000). The putative proteolytic activation site is indicated by “∥”. The catalytic residues at the active site are highlighted by “▲”, whereas residues determining the primary specificity of HP21 are labeled with “@”.

M. sexta HP21 may share a common disulfide network with HP2, HP13, HP18, and HP22 (Jiang et al., 2005). The clip and catalytic domains in these enzymes contain six disulfide bonds that are absolutely conserved in arthropod clip-domain serine proteinases (Jiang and Kanost, 2000; Ross et al., 2003). Cys265 and Cys358 in the catalytic domain probably pair with two of the four Cys residues (Cys96, Cys116, Cys127, and Cys145) in the linker region. Since Cys265 is always a partner of interdomain disulfide linkage in the clip-domain proteinases, so must be Cys358. Consequently, after proHP21 is proteolytically activated, its amino-terminal light chain (17.0 kDa) and carboxyl-terminal heavy chains (27.5 kDa) are probably tethered by two interchain disulfide bridges. These two bonds may also be present in D. melanogaster Snake (Fig. 1B) and Sp48, Anopheles gambiae ClipC3 (Sp18D), and Ctenocephalides felis Sp8, all of which are Group-Ia clip-domain enzymes (Ross et al., 2003). In addition to that, M. sexta HP2, HP13, HP18, HP21 and HP22 may contain a unique disulfide bond formed between the two remaining Cys residues in the linker region.

3.2. Production and characterization of recombinant proHP21

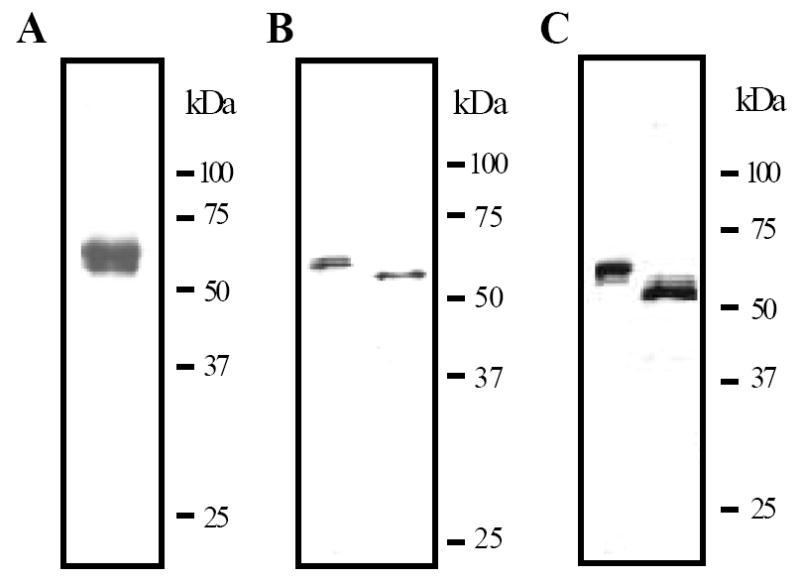

We expressed HP21 precursor in a baculovirus/insect cell system. To optimize the expression conditions, we infected Sf9 and Sf21 cells for 72 to 96 h. The proHP21 level in the culture medium was highest with Sf9 cells between 72 and 84 h. Protein degradation became noticeable at 96 h post infection. Under optimal conditions, we expressed proHP21 in 40 ml of Sf9 cells. The recombinant protein in the conditioned medium was enriched on a Q-Sepharose column and further purified by affinity chromatography on a Ni2+-column. The recovered proHP21 migrated as a broad band with apparent molecular masses between 57 and 60 kDa (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic analysis of M. sexta proHP21 from baculovirus-infected insect cells.

The purified recombinant HP21 precursor (0.2 μg) was subjected to electrophoresis on a 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel under reducing condition. The protein is visualized by silver staining (A). As described in Materials and methods, proHP21 was treated with buffer (left lanes), PNGase F (B) or O-glycosidase (C), separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and detected using HP21 antibodies. Sizes and positions of the molecular mass markers are indicated on the right.

The isoelectric point of proHP21 was found to be 6.0, close to the pI calculated based on the hexahistidine-tagged protein sequence (5.85). The average molecular mass of proHP21, as determined by MALDI mass spectrometry, was 51,118 Da, larger than the value calculated for the recombinant protein (44,430 Da). The mass difference (approximately 6,688 Da) resulted from N- and O-linked glycosylation (Fig. 2B and 2C). The MH2+ peaks were better resolved than the MH+ peaks, confirming that the fusion protein was heterogeneous. We identified three broad overlapping peaks with an estimated relative abundance of 3:10:1 and corresponding MH+ masses of 52.2, 51.1 and 49.7 kDa.

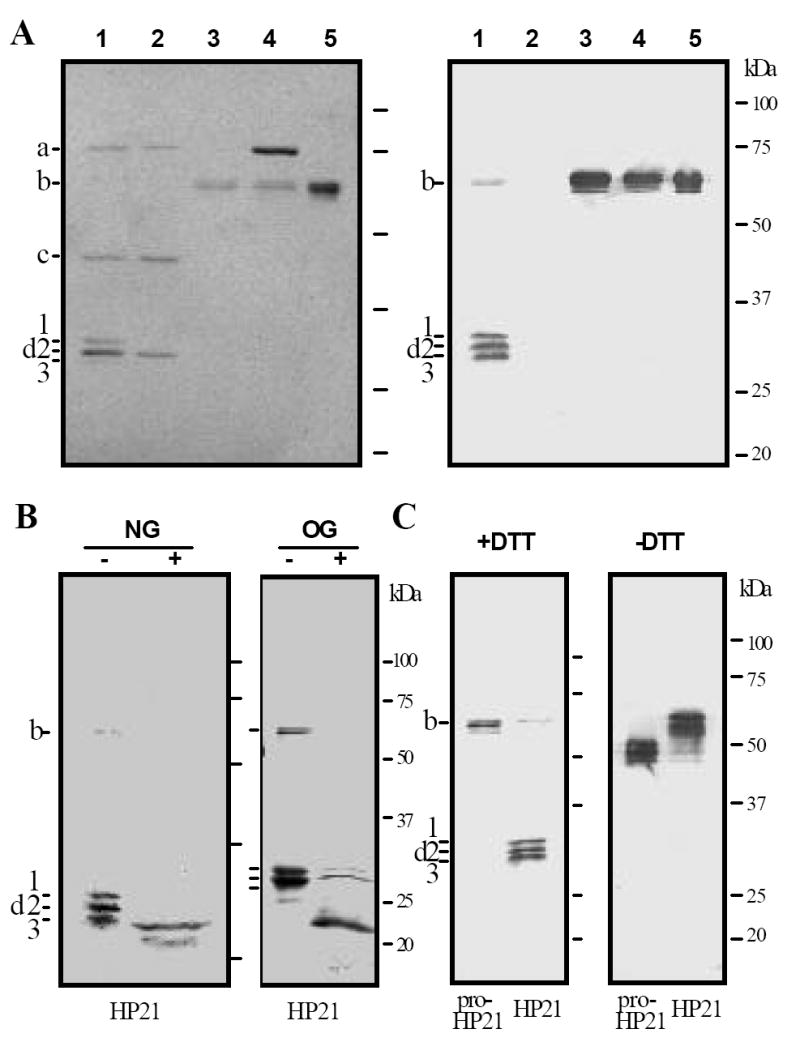

3.3. Cleavage activation of proHP21 by HP14

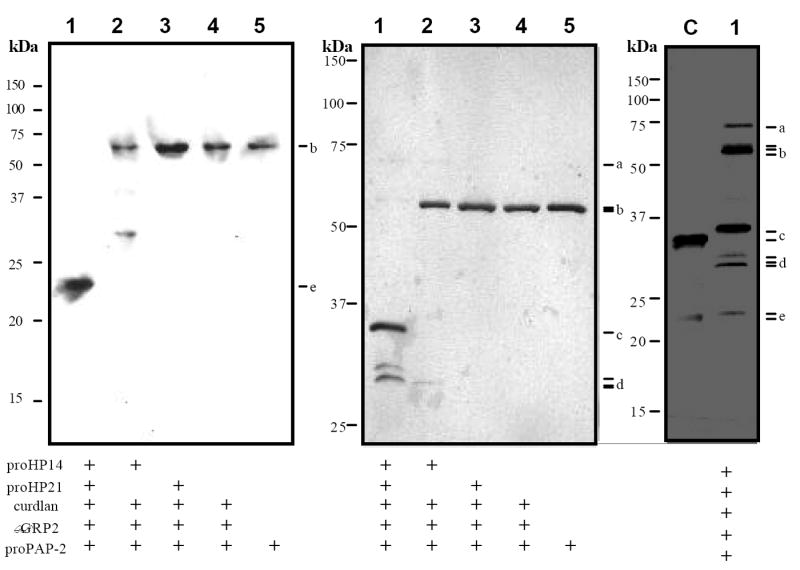

To test whether or not autoactivated HP14 could cleave proHP21, we incubated purified proHP21 with proHP14, βGRP2, and curdlan. Immunoblot analysis following SDS-PAGE revealed three new bands (d1, d2 and d3) at 31, 30 and 29 kDa positions (lane 1, Fig. 3A). Silver staining showed that these bands appeared only after proHP21 had been incubated with active HP14: d1 was absent in the controls, d2 co-migrated with the catalytic domain of HP14, and d3 was barely detected. In-gel trypsin digestion and mass fingerprint analysis of d1 and d2 revealed 3, 3, 13, and 7 fragments from HP21 clip domain, linker region, catalytic domain, and HP14 catalytic domain (Table 1), respectively. Antibody reactivity indicated that d3 polypeptide, like d1 and d2, was a part of HP21 (Fig. 3A and 3C, right panels; Fig. 3B). The HP21-derived bands, absent in the proHP14 activation mixture (lane 2), were not detected in the purified proHP21 or proHP21 incubated with curdlan and βGRP2. Neither did incubation with proHP14 lead to proteolytic activation of proHP21. In other words, binding of β-1,3-glucan by its recognition protein did not activate proHP21 directly, and cleavage of proHP21 occurred only after HP14 was generated in the presence of curdlan and βGRP2.

Figure 3. Proteolytic processing of M. sexta HP21 precursor after exposure to autoactivated HP14.

(A) Purified proHP21 (60 ng, 3 μl), proHP14 (60 ng, 3 μl), curdlan (10 μg, 1 μl), βGRP2 (40 ng, 2 μl), and buffer C (15 μl) were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction mixture and negative controls were treated with SDS-sample buffer, separated by 10% SDS-PAGE under reducing condition, and visualized by silver staining (left panel) or immunoblotting using HP21 antibodies (right panel). Lane 1, all the components; lane 2, all but proHP21; lane 3, all but proHP14; lane 4, proHP14 and proHP21; lane 5, proHP21 only. (B) To locate glycosylation sites, active HP21 (60 ng) was generated as described in (A) and then treated with H2O (-), PNGase F (NG, +), or O-glycosidase (OG, +). Following 10% SDS-PAGE under reducing condition, HP21 was transferred and detected using HP21 antibodies. (C) To examine the interchain disulfide bonds and their effect on mobility, proHP21 and HP21 were treated with SDS sample buffer containing dithiothreitol (+DTT) or not (-DTT), separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and subjected to immunoblot analysis. a, 75 kDa proHP14; b, 60 kDa proHP21 and βGRP2; c, 45 kDa HP14 heavy chain; d, ~30 kDa HP14 and HP21 catalytic domain, as well as HP21 light chain. Sizes and positions of the molecular mass markers are indicated on the right.

Table 1.

PTH-amino acid(s) detected a-b or expected c-e in automated Edman degradation of d1 (a), d2 (b), HP21 clip (c) and catalytic (d) domains, and HP14 catalytic domain (e)

| Cycle # | a | b | c | d | e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ala, Ile, Val | Ala, Ile, Val | Ala | Ile | Val |

| 2 | Asp, Ile, Leu | Asp, Ile, Leu | Asp | Ile | Leu |

| 3 | Glu, Gly, Gly | Glu, Gly, Gly | Glu | Gly | Gly |

| 4 | Asn, Gly, Gly | Asn, Gly, Gly | Asn | Gly | Gly |

| 5 | Glu, Gln, (Glu) | Glu, Gln, (Glu) | Glu | Gln | Glu |

| 6 | Thr, (Asn), Arg | Thr, (Asn) | Thr | Asn | Arg |

| 7 | (Cys), Ala, (Ala) | (Cys), Ala, (Ala) | Cys | Ala | Ala |

| 8 | Asn, Ser, Gln | not determined | Asn | Ser | Gln |

| 9 | Met, Phe | not determined | Met | Arg | Phe |

| 10 | Lys, Asn, Gly | not determined | Lys | Asn | Gly |

To further characterize the cleavage reaction, we determined the position of scissile bond in HP21 by automated Edman degradation. Sequence data (Table 1) revealed three polypeptides in d1 and d2: the amino-terminal light chain of HP21, the carboxyl-terminal heavy chain of HP21, and the catalytic domain of HP14. In the first five cycles, all the expected phenylthioazolinone (PTH) amino acids were detected – the detection of PTH-Asn in cycle 4 indicated that Asn4 was unmodified. The mass fingerprint analysis (Table 2) showed that the calculated masses of Ala-Asp-Glu-Asn4-Glu-Thr-Cys-Asn-Met-Lys and Asp-Ile-Asn205-Leu-Thr-Tyr-Val-Tyr-Leu-Gly-Ala-Leu-Ala-Arg matched the observed masses. On the other hand, Asn158 in the context of Asn158-Ala-Ser was probably N-glycosylated, because an unknown PTH-amino acid eluted in cycle 6 at a retention time different from all the PTH-amino acid standards. We did not detect PTH-Arg from d1 in cycle 9, as we did previously (Wang and Jiang, 2006). Based on these data, we concluded that: 1) the amino-terminal light chain of HP21 (Ala1 to Leu152) began at the predicted starting site of mature proHP21 (Fig. 1); 2) HP14, which cut itself immediately after Leu387 (Wang and Jiang, 2006) and hydrolyzed Ala-Ala-Pro-Leu-p-nitroanilide (Ji et al., 2004), cleaved proHP21 at the predicted activation site between Leu152 and Ile153.

Table 2.

Trypsinolytic peptides from bands d1 and d2 matched with the deduced sequence of HP21

| Calculated mass | Observed mass a | Δ | start | end | sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1227.645 | 1227.462 | .183 | 1 | 10 | (-)ADENETCNMK(N) |

| 1173.569 | 1173.569 | .000 | 22 | 31 | (R)NCPSALENLR(K) |

| 1205.601 | 1205.599 | .002 | 34 | 43 | (R)IQPQLCGFDK(S) |

| 969.456 | 969.435 | .021 | 116 | 122 | (K)CLEYQEK(L) |

| 908.458 | 908.455 | .003 | 123 | 129 | (K)LVYPCEK(S) |

| 1369.643 | 1369.642 | .001 | 130 | 141 | (K)SFSLSLNDAMER(K) |

| 1581.863 | 1581.864 | -.001 | 203 | 216 | (R)DINLTYVYLGALAR(S) |

| 862.414 | 862.416 | -.002 | 217 | 224 | (R)SEVTDPSK(Q) |

| 1049.552 | 1049.553 | -.001 | 234 | 242 | (K)HPEFAPPVR(Y) |

| 1334.693 | 1334.696 | -.003 | 243 | 253 | (R)YNDIALVELER(N) |

| 2682.245 | 2682.229 | .016 | 254 | 276 | (R)NVPLDEWLKPACLHMGDETADDR(V) |

| 1410.700 | 1410.706 | -.006 | 277 | 288 | (R)VWATGWGLTEYK(A) |

| 988.5350 | 988.543 | -.008 | 289 | 298 | (K)ASSGANILQK(V) |

| 1794.860 | 1794.864 | -.004 | 304 | 317 | (K)FSTFECILQYPPHR(L) |

| 2007.834 | 2007.836 | -.002 | 318 | 334 | (R)LMSQGFDVNSQMCYGDR(S) |

| 1475.681 | 1475.680 | .001 | 339 | 352 | (K)DTCQGDSGGPLQIK(H) |

| 1738.865 | 1738.902 | -.037 | 356 | 370 | (K)INCMWLIIGVTSFGK(A) |

| 1412.691 | 1412.688 | .003 | 371 | 383 | (K)ACGFIGEPGIYTK(V) |

| 2776.372 | 2776.365 | .007 | 384 | 405 | (K)VSHYIPWIESVVWPLEHHHHHH(-) |

: monoisotopic mass in Da. The starting and ending numbers for individual tryptic peptides ere based on the deduced amino acid sequence of mature proHP21.

Co-migration of HP21 light chain (Ala1 to Leu152) with its heavy chain (Ile153 to His405) was mainly caused by severe O-glycosylation in the linker region (Val51 to Leu152). Deglycosylation with PNGase F reduced apparent molecular masses from 29~31 to 28~29 kDa (Fig. 3B). Consistent with the small mobility change, we only found two N-linked glycosylation sites (Asn102-Leu-Thr, Asn158-Ala-Ser) in the light and heavy chains. In contrast, there are 10 putative O-linked glycosylation sites (Ser53 and Thr55, 56, 60, 66-68, 74-76), all located near the beginning of the linker sequence. O-glycosidase treatment yielded in a strong immunoreactive band at around 22 kDa (Fig. 3B), confirmed to be the light chain by trypsinolytic peptide mass fingerprint analysis (data not shown). The faint bands at the 30 and 31 kDa positions represent the heavy chain of HP21 – polyclonal antibodies against clip-domain serine proteinases reacted with the clip domains stronger than with the catalytic domains (Jiang et al., 2003a, 2003b and 2005). Under nonreducing condition, active HP21 migrated as a series of bands around 50 kDa (Fig. 3C), indicating that the light and heavy chains remained attached by interchain disulfide bonds. The unreduced HP21 had lower gel mobility than proHP21 did.

3.4. Enzymatic activity of HP21

Although HP21 was predicted to be a trypsin-like proteinase, we did not detect any significant amidase activity using the synthetic substrates. To demonstrate proHP21 became an active enzyme after HP14 cleavage, we tested the formation of SDS-stable complex of HP21 and serpin-4, a suicidal inhibitor that traps active proteinases only. M. sexta serpin-4 was identified as a physiological regulator of HP21 and two other HPs (Tong et al., 2005). When proHP21 was cleaved by HP14 in the presence of purified recombinant serpin-4, an extra band was detected by immunoblot analysis using serpin-4 antibodies (Fig. 4). This band, absent in the negative controls that lacked proHP14, proHP21 or serpin-4, had an apparent molecular mass of 74 kDa, which is close to what was predicted for the complex of HP21 catalytic domain and serpin-4. HP21 antibodies recognized a band at the same size. These data indicated that HP21 activated in vitro formed a stable complex with M. sexta serpin-4.

Figure 4. Formation of an SDS-stable complex of M. sexta HP21 and serpin-4.

ProHP14 (40 ng, 2 μl), proHP21 (40 ng, 2 μl), curdlan (20 ng, 1 μl), βGRP2 (40 ng, 2 μl), serpin-4 (0.2 μg, 2 μl), and buffer C (15 μl) were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. In the controls, proHP14, proHP21, or serpin-4 in the reaction mixture was replaced by the same volume of buffer C. The reaction and control samples were separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE under reducing condition. Immunoblot analysis was performed using 1:1,000 diluted serpin-4 (left panel) or HP21 (right panel) antiserum at the first antibody. a, 50 kDa serpin-4; b, 60 kDa proHP21; c, ~30 kDa HP21 heavy and light chains; *, 75 kDa complex of serpin-4 and HP21 catalytic chain. Sizes and positions of the molecular mass markers are indicated.

As the next step to characterize the inhibition, we determined the cleavage site of serpin-4 by MALDI mass spectrometry. In the reaction containing curdlan, βGRP2, proHP14, proHP21, and serpin-4, we detected a 4,253.2 Da peak, which is identical in molecular mass to a carboxyl-terminal fragment of serpin-4 (Ile356 to Tyr391, 4,254.1 Da). This peak, absent in the control of serpin-4 only or in the activation reaction without serpin-4, represents the carboxyl-terminal peptide released upon cleavage between Arg355 and Ile356. In other words, HP21 has a trypsin-like specificity indeed and the P1 residue of serpin-4 is Arg355.

3.5. Role of HP21 in proPO activation

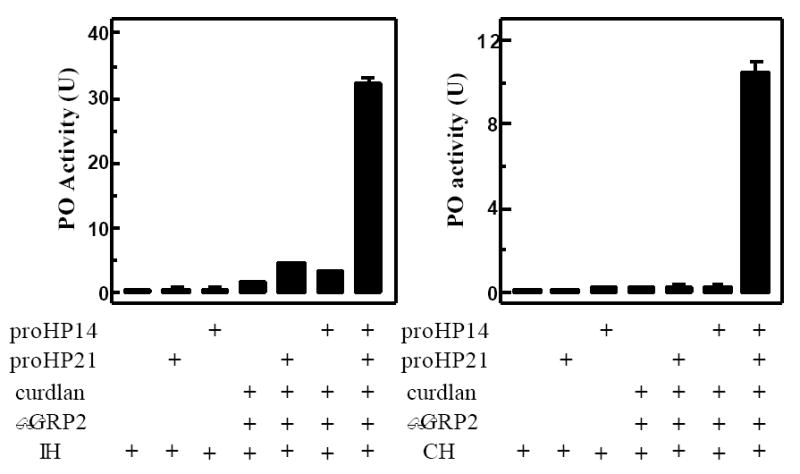

To probe its physiological role, we produced active HP21 by incubating proHP21 with curdlan, βGRP2 and proHP14. After removing the elicitor and its binding protein by centrifugation, we added supernatants from the reaction and controls to the diluted plasma from M. sexta larvae injected with bacteria. The cell-free hemolymph had a low PO activity, and this activity did not increase when proHP14 or proHP21 was added (Fig. 5A). There was a small increase in PO activity after the plasma had been incubated with the supernatant of curdlan and βGRP2. This increase probably resulted from residual curdlan in the supernatant, and coexistence of proHP14 or proHP21 enhanced the proPO activation. While PO activity in these controls was 0.4-4.0 U, this activity became much higher (30 U) when both proHP14 and proHP21 were present in the preincubation mixture. Similar results were obtained when plasma from the naïve larvae was used (Fig. 5B). Therefore, HP21, as well as HP14, is a component of the M. sexta proPO activation system.

Figure 5. Role of M. sexta HP21 in the proPO activation system.

Purified proHP14 (40 ng, 2 μl), proHP21 (80 ng, 2 μl), βGRP2 (40 ng, 2 μl), curdlan (100 μg, 10 μl), and buffer C (14 μl) were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After centrifugation, 5 μl of the supernatant was reacted with 5 μl of 1:10 diluted plasma from induced (left panel, IH) or naïve (right panel, CH) larvae, 1 μl of M. luteus (10 μg), and buffer C (39 μl) on ice for 30 min. PO activity in the reaction mixture was assayed using dopamine as a substrate (Jiang et al., 2003a) and plotted as mean ± S.D. (n=3) in the bar graph. The pre-incubation mixture without proHP14 and/or proHP21 was used as controls.

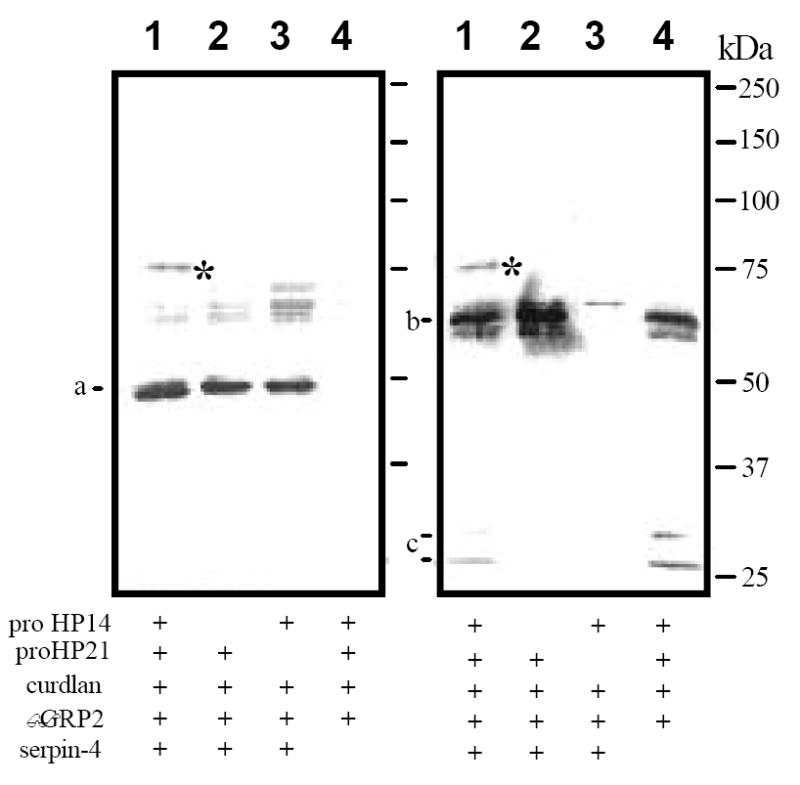

3.6. Search for a protein substrate of HP21

In an effort to reconstitute the proPO activation system in vitro, we tested whether or not HP21 could activate proPAP-2. ProPAP-2 contains a positively charged residue preceding the cleavage activation site (i.e., Lys153), which fits with the specificity of HP21. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, HP21 cut proPAP-2 into two fragments (Fig. 6, lane 1): the 23 kDa band, strongly recognized by PAP-2 antibodies, is nearly identical in size to the amino-terminal light chain of PAP2 isolated from the plasma (lane C) (Jiang et al., 2003a), and the 35 kDa band, weakly reacted with the polyclonal antibodies, represents the carboxyl-terminal heavy chain. Edman degradation indicated that the 35 kDa polypeptide started with Ile-Leu-Gly-Gly-Glu, identical to the amino terminus of the PAP-2 catalytic domain (I154LGGE158) (Jiang et al., 2003a). Therefore, the proteolysis occurred between Lys153 and Ile154. With a hexahistidine affinity tag attached to the carboxyl terminus, the heavy chain migrated slower than its counterpart from the hemolymph. The heavy and light chains were not detected in proPAP-2 (lane 5) or activation mixture lacking proHP14 (lane 3). Active HP14 by itself slightly cleaved proPAP-2, but the resulting products had different sizes (lane 2). In the absence of proHP14 and proHP21 (lane 4), curdlan and βGRP2 did not activate proPAP-2. Therefore, it was the active HP21 that cleaved proPAP-2 at Lys153.

Figure 6. Proteolytic processing of M. sexta proPAP-2 by HP21.

Purified βGRP2, proHP14, proHP21 and curdlan (amounts as in Fig. 3) were incubated with proPAP-2 (0.4 μg, 2 μl), and buffer C (15 μl) at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction mixture (12 μl, lane 1), controls (12 μl, lanes 2-5), and PAP-2 purified from the larval hemolymph (lane C, 0.1 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE under the reducing condition. The protein bands were detected by immunoblot analysis using PAP-2 antibodies (left panel, 12% gel) or silver staining (middle panel, 10% gel; right panel, 12% gel, over development). a, 75 kDa proHP14; b, 62 kDa βGRP2, 60 kDa proHP21 and 56 kDa proPAP-2; c, ~35 kDa catalytic domain of natural and recombinant PAP-2; d, ~30 kDa HP14 and HP21 catalytic domains and HP21 light chain; e, ~24 kDa light chain of natural and recombinant PAP-2. Sizes and positions of the molecular mass markers are indicated.

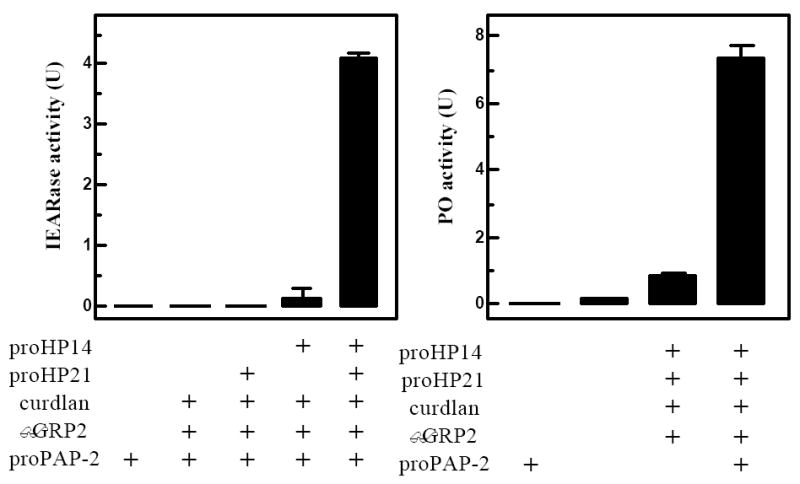

3.7. Activities of HP21-generated PAP-2

To confirm that the recombinant proPAP-2 became active after HP21 cleavage, we measured amidase activity in the reaction supernatant (Fig. 7A). No activity was detected in the negative control of proPAP-2 alone or proPAP-2 incubated with curdlan, βGRP2 and proHP21. While IEARpNA could be slightly hydrolyzed after proPAP-2 had been incubated with HP14, the amidase activity (0.2 U) was much lower than when proHP21 was also present (4.1 U). Since HP14 or HP21 does not hydrolyze the substrate (data not shown), cleaved PAP2 is responsible for the activity.

Figure 7. Enzymatic activities of PAP-2 generated in vitro.

Amidase activities in the supernatants of the reaction and control mixtures were determined using 150 μl of 100 μM of IEARpNA (Jiang et al., 2003a) and plotted as mean ± S.D. (n=3) (left panel). To measure proPO activation, 10 μl supernatants were incubated with proPO (0.2 μg, 1 μl), SPHs (40 ng, 2 μl), and buffer C (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 17 μl) on ice for 40 min. PO activities in the reaction and control mixtures were assayed and plotted similarly (right panel).

Can PAP-2 activated in vitro cleave proPO and generate active PO in the presence of SPH-1 and SPH-2? To address this question, we first incubated proPAP-2 with curdlan, βGRP2, proHP14, and proHP21. After removing βGRP2-associated curdlan, the supernatant (containing active PAP-2) was reacted with proPO and SPHs (Fig. 7B). Little PO activity was detected in proPO alone or proPO reacted with proPAP-2. There was a small activity increase (0.8 U) after active HP14 and HP21 had been incubated with proPO and SPHs, and this increase became more prominent (7.4 U) when proPAP-2 was also included in the preincubation mixture. In conclusion, cleaved PAP-2 and its “cofactor” activated proPO, and we successfully reconstituted a branch of the proPO cascade in vitro using purified proteins.

4. Discussion

The hemolymph of M. sexta larvae contains at least 25 serine proteinases, and some of these HPs are components of the proPO activation cascade (Jiang et al., 2005). HP14, a first member of the pathway, becomes active when its precursor interacts with peptidoglycan or β-1,3-glucan (Ji et al., 2004, Wang and Jiang, 2006). Based on the specificity of HP14, we postulated that the precursor of HP2, HP13, HP16, HP19, HP21 or HP22 could be a substrate of HP14. A recent study on M. sexta serpin-4 and serpin-5 suggested that HP1, HP6, HP8, HP17, and HP21 are members of the proPO activation or other immune proteinase pathways (Tong et al., 2005). Since HP21 appeared on both lists, we chose to characterize proHP21 and test whether it is a substrate of HP14. In this paper, we provide biochemical evidence that M. sexta HP21, a clip-domain serine proteinase most similar to Drosophila Snake in terms of sequence similarity and disulfide connectivity (Fig. 1), serves as a link between HP14 and PAP-2 in the proPO activation cascade: HP14-cleaved HP21 activated proPAP-2 by limited proteolysis (Fig. 3 and Fig. 6). HP21 generated in vitro cleaved serpin-4 at Arg355 and formed an inactive complex with the inhibitor (Fig. 4), and the same complex was detected in the larval hemolymph (Tong et al., 2005). Addition of active HP21 greatly enhanced melanization in the plasma of M. sexta larvae (Fig. 5). Using proteins isolated from M. sexta hemolymph or baculovirus-infected insect cells, we demonstrated how recognition of a pathogen-associated molecular pattern (β-1,3-glucan) leads to a host defense response (melanization): binding of curdlan and βGRP2 triggers the autoactivation of proHP14 (Wang and Jiang, 2006), HP14 processes proHP21, HP21 cleaves proPAP-2, PAP-2 activates proPO in the presence of SPHs (Fig. 7), and PO produces quinones and melanin. To our knowledge, this is the first time that anyone has reconstituted an entire branch of the insect proPO activation system in vitro.

The entire proteinase system for proPO activation in M. sexta is more complex than what we have shown so far. First and foremost, activation of proPO by PAPs requires cleaved SPH-1 and SPH-2 (Jiang et al., 2003a). We expressed both pro-SPHs in a baculovirus-insect cell system and found them inactive as “cofactors” (data not shown). Probably, as demonstrated in a beetle (Kim et al., 2002), pro-SPHs also need proteolytic activation – cleaved SPHs are catalytically inactive but active in assisting PAP to produce active PO. In that case, what is M. sexta pro-SPH activating proteinase and how does it become active in response to pathogen infection? Our collection of purified hemolymph proteins and their antibodies (Jiang et al., 2005) is expected to aid in the elucidation and reconstitution of the pro-SPH activation branch.

Like PAP-2, M. sexta PAP-1 or PAP-3 also activates proPO in the presence of SPH-1 and SPH-2 (Yu et al., 2003). While HP21 converts proPAP-3 to PAP-3 (Gorman et al., 2007), it is unclear how proPAP-1 becomes active: preliminary data did not support HP21 as a universal activator of the proPAPs. Therefore, we are beginning to test if other trypsin-like HPs could cut proPAP-1 at its activation site. Our model of the M. sexta proPO activation system indicates that HP1, HP6, and HP8 are good candidates for that function (Tong et al., 2005). If one of the HPs is confirmed to activate proPAP-1, it would be interesting to find out how it connects to the pathway presented in this paper.

M. sexta HP2, HP13, HP16, HP19, and HP22 precursors all contain a Leu residue at their putative activation sites (Jiang et al., 2005). Could HP14 activate any of them, and what defense response would that proteinase lead to? The phylogenetic analysis showed that HP16 and HP19 are similar in their catalytic domain sequences to Drosophila gastrulation defective, the second component of the SP cascade that establishes the dorsoventral axis. Perhaps, it is worth testing their roles in the proteolytic activation of M. sexta plasmatocyte-spreading peptide and spätzle precursors (Wang et al., 1999 and 2007). Recently, Drosophila Sp4 (CG16705) was found to be a processing enzyme of spätzle, which activates the Toll-dependent antimicrobial response (Jang et al., 2006).

HP21 is similar in amino acid sequence to D. melanogaster Snake (Fig. 1), A. gambiae ClipC1, ClipC3 (Christophides et al., 2002; Gorman et al., 2000), M. sexta HP2, HP13, HP18, HP22 (Jiang et al., 2005), and Ctenocephalides felis Sp8 (Gaines et al., 1999). While biochemical functions are unknown for most of these clip-domain serine proteinases, Northern blot and RT-PCR analyses revealed that the mRNA levels of HP2, HP13, HP18, HP21, and HP22 increased in the larval fat body and/or hemocytes after a bacterial injection, suggesting that these enzymes all play certain roles in defense responses (Jiang et al., 2005). Due to higher sequence similarities with PAPs, current research on melanization in A. gambiae is focused on members of the B group (Volz et al., 2005; Paskewitz et al., 2006). RNA interference tests showed close associations of ClipB4, ClipB8, ClipB14, and ClipB15 with melanization of Sephadex beads or Plasmodium ookinetes. In light of our findings on M. sexta HP21, it is, perhaps, a good time to investigate the possible role of A. gambiae ClipC1 or ClipC3 in melanization. While constitutive expression of ClipC3 was detected in all developmental stages tested and there was no change in its mRNA abundance after immune challenge (Christophides et al., 2002), ClipC1 would be a more promising target for gene silencing experiments. It is our hope that results from biochemical analyses, such as the one presented herein, could provide useful clues for research on arthropods that transmit serious human diseases. Furthermore, our ongoing X-ray and NMR structural analyses of proHP21 and proPAP-2 are expected to yield useful information on how clip and catalytic domains of these proteinases interact with each other.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Maureen Gorman and Jack Dillwith for their helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM58634. This article was approved for publication by the Director of the Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station and supported in part under project OKLO2450.

Abbreviations

- PO and proPO

phenoloxidase and its proenzyme

- PAP and proPAP

proPO activating proteinase and its precursor

- HP

hemolymph proteinase

- SPH

serine proteinase homolog

- βGRP2

β-1,3-glucan recognition protein-2

- MALDI-TOF

matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight

- IEARpNA

acetyl-Ile-Glu-Ala-Arg-p-nitroanilide

- PTH

phenylthioazolinone

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Footnotes

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBank™/EBI Data bank with accession number(s) AY627797.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ashida M, Brey PT. Recent advances on the research of the insect prophenoloxidase cascade. In: Brey PT, Hultmark D, editors. Molecular Mechanisms of Immune Responses in Insects. Chapman & Hall; London: 1998. pp. 135–172. [Google Scholar]

- Christophides GK, Zdobnov E, Barillas-Mury C, Birney E, Blandin S, et al. Immunity-related genes and gene families in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2002;298:159–165. doi: 10.1126/science.1077136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F, Sakal R, Vernick K, Paskewitz S, Miller D, Collins W, Campbell C, Gwadz R. Genetic selection of a Plasmodium-refractory strain of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Science. 1986;234:607–610. doi: 10.1126/science.3532325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn P, Drake D. Fate of bacteria injected into naive and immunized larvae of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. J Invertebr Pathol. 1983;41:77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Gaines PJ, Sampson CM, Rushlow KE, Stiegler GL. Cloning of a family of serine protease genes from the cat flea Ctenocephalides felis. Insect Mol Biol. 1999;8:11–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1999.810011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie JP, Kanost MR, Trenczek T. Biological mediators of insect immunity. Ann Rev Entomol. 1997;42:611–643. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman M, Andreeva OV, Paskewitz SM. Molecular characterization of five serine protease genes cloned from Anopheles gambiae hemolymph. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;30:35–46. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(99)00095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman M, Wang Y, Jiang H, Kanost MR. Manduca sexta hemolymph proteinase 21 activates prophenoloxidase activating proteinase-3 in an insect innate immune response proteinase cascade. J Biol Chem. 2006;282 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611243200. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JA. The immune response of Drosophila. Nature. 2003;426:33–38. doi: 10.1038/nature02021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang I-H, Chosa N, Kim SH, Nam HJ, Lemaitre B, Ochiai M, Kambris Z, Brun S, Hashimoto C, Ashida M, Brey PT, Lee WJ. A Spatzle-processing enzyme required for toll signaling activation in Drosophila innate immunity. Dev Cell. 2006;10:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji C, Wang Y, Guo X, Hartson S, Jiang H. A pattern recognition serine proteinase triggers the prophenoloxidase activation cascade in the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34101–34106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404584200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji C, Wang Y, Ross J, Jiang H. Expression and in vitro activation of Manduca sexta prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase-2 precursor (proPAP-2) from baculovirus-infected insect cells. Protein Exp Purif. 2003;23:328–337. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(03)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Kanost MR. The clip-domain family of serine proteinases in arthropods. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;30:95–105. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(99)00113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Ma C, Lu Z, Kanost MR. β-1,3-glucan recognition protein-2 (βGRP-2) from Manduca sexta: an acute-phase protein that binds β-1,3-glucan and lipoteichoic acid to aggregate fungi and bacteria. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wang Y, Gu Y, Guo X, Zou Z, Scholz F, Trenczek T, Kanost MR. Molecular identification of a bevy of serine proteinases in Manduca sexta hemolymph. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;35:931–943. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wang Y, Kanost MR. Pro-phenol oxidase activating proteinase from an insect, Manduca sexta: a bacteria-inducible protein similar to Drosophila easter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12220–12225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wang Y, Ma C, Kanost MR. Subunit composition of pro-phenol oxidase from Manduca sexta: molecular cloning of subunit proPO-p1. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;27:835–850. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(97)00066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wang Y, Yu X-Q, Kanost MR. Prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase-2 (PAP-2) from hemolymph of Manduca sexta: a bacteria-inducible serine proteinase containing two clip domains. J Biol Chem. 2003a;278:3552–3561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wang Y, Yu X-Q, Zhu Y, Kanost MR. Prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase-3 (PAP-3) from Manduca sexta hemolymph: a clip-domain serine proteinase regulated by serpin-1J and serine proteinase homologs. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003b;33:1049–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(03)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanost MR, Jiang H, Yu X-Q. Innate immune responses of a lepidopteran insect, Manduca sexta. Immunol Rev. 2004;198:97–105. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Baek M, Lee M, Park J, Lee S, Söderhäll K, Lee BL. A new easter-type serine protease cleaves a masquerade-like protein during prophenoloxidase activation in Holotrichia diomphalia larvae. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39999–40004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon T, Kim M, Choi H, Joo C, Cho M, Lee BL. A masquerade-like serine proteinase homologue is necessary for phenoloxidase activity in the coleopteran insect, Holotrichia diomphalia larvae. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6188–6196. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavine MD, Strand MR. Insect hemocytes and their role in immunity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;32:1295–1309. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(02)00092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Kwon T, Hyun J, Choi J, Kawabata S, Iwanaga S, Lee BL. In vitro activation of pro-phenol-oxidase by two kinds of pro-phenol-oxidase-activating factors isolated from hemolymph of coleopteran, Holotrichia diomphalia larvae. Eur J Biochem. 1998;254:50–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nappi AJ, Christensen BM. Melanogenesis and associated cytotoxic reactions: applications to insect innate immunity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;35:443–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nappi AJ, Vass E. Cytotoxic reactions associated with insect immunity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;484:329–348. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1291-2_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paskewitz SM, Andreeva OV, Shi L. Gene silencing of serine proteases affects melanization of Sephadex beads in Anopheles gambiae. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;36:701–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perona JJ, Craik CS. Structural basis of substrate specificity in the serine proteases. Protein Sci. 1995;4:337–360. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J, Jiang H, Kanost MR, Wang Y. Serine proteases and their homologs in the Drosophila melanogaster genome: an initial analysis of sequence conservation and phylogenetic relationships. Gene. 2003;304:117–131. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y, Jiang H, Kanost MR. Identification of plasma proteases inhibited by Manduca sexta serpin-4 and serpin-5 and their association with components of the prophenol oxidase activation pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14932–14942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500532200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Cheng T, Rayaprolu S, Zou Z, Xia Q, Xiang Z, Jiang H. Proteolytic activation of pro-spätzle is required for the induced transcription of antimicrobial peptide genes in lepidopteran insects. Dev Comp Immunol. 2007;31 doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2007.01.001. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Jiang H. Prophenoloxidase (PPO) activation in Manduca sexta: an initial analysis of molecular interactions among PPO, PPO-activating proteinase-3 (PAP-3), and a cofactor. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:731–742. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Jiang H. Interaction of β-1,3-glucan with its recognition protein activates hemolymph proteinase 14, an initiation enzyme of the prophenoloxidase activation system in Manduca sexta. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9271–9278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513797200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Jiang H, Kanost MR. Biological activity of Manduca sexta paralytic and plasmatocyte spreading peptide and primary structure of its hemolymph precursor. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;29:1075–1086. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(99)00086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz J, Osta MA, Kafatos FC, Muller HM. The roles of two clip domain serine proteases in innate immune responses of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40161–40168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506191200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X-Q, Jiang H, Wang Y, Kanost MR. Nonproteolytic serine proteinase homologs are involved in phenoloxidase activation in the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33:197–208. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(02)00191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]