Abstract

Polyprolines are well known for adopting a regular polyproline type II helix in aqueous solution, rendering them a popular standard as molecular ruler in structural molecular biology. However, single-molecule spectroscopy studies based on Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) have revealed deviations of experimentally observed end-to-end distances of polyprolines from theoretical predictions, and it was proposed that the discrepancy resulted from dynamic flexibility of the polyproline helix. Here, we probe end-to-end distances and conformational dynamics of poly-l-prolines with 1–10 residues using fluorescence quenching by photoinduced-electron transfer (PET). A single fluorophore and a tryptophan residue, introduced at the termini of polyproline peptides, serve as sensitive probes for distance changes on the subnanometer length scale. Using a combination of ensemble fluorescence and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, we demonstrate that polyproline samples exhibit static structural heterogeneity with subpopulations of distinct end-to-end distances that do not interconvert on time scales from nano- to milliseconds. By observing prolyl isomerization through changes in PET quenching interactions, we provide experimental evidence that the observed heterogeneity can be explained by interspersed cis isomers. Computer simulations elucidate the influence of trans/cis isomerization on polyproline structures in terms of end-to-end distance and provide a structural justification for the experimentally observed effects. Our results demonstrate that structural heterogeneity inherent in polyprolines, which to date are commonly applied as a molecular ruler, disqualifies them as appropriate tool for an accurate determination of absolute distances at a molecular scale.

Keywords: fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, molecular ruler, prolyl isomerization, biopolymer, Förster resonance energy transfer

Fluorescence spectroscopy provides a variety of tools to measure distances, monitor dynamics, or observe molecular interactions with sensitivity far beyond that of other biophysical techniques. Distance-dependent interactions between fluorophores and fluorescence-quenching molecular compounds, such as Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) or photoinduced electron transfer (PET), are capable of reporting on processes on the nanometer length scale, below the diffraction limit generally imposed on optical techniques. Although much information is gained from relative distances or distance changes, the quest for precise determination of absolute distances has been ongoing ever since Stryer and Haugland presented the application of FRET as a spectroscopic ruler (1). FRET is a nonradiative dipole–dipole interaction between two fluorophores (donor D and acceptor A) that can serve as a spectroscopic ruler on length scales between ≈2 and ≈10 nm (2–6). Structurally well defined model systems (molecular rulers) are needed for validation of spectroscopic rulers as much as the latter are essential for structural investigations. Since the seminal work of Stryer and Haugland with polyprolines as a molecular ruler, both polypeptides and polynucleotides with well defined structures were used to validate Förster theory (4, 7–11).

Proline is unique among the natural amino acids in having a side chain that is cyclized to the backbone, restricting its conformational space considerably (12). Polyprolines have been characterized by various spectroscopic techniques (1, 7, 8, 13–21). Two main conformations depending on the isomerization state of the prolyl bond were identified: the polyproline type I helix (PPI) with all peptide bonds in the cis conformation (14); and the polyproline type II helix (PPII) with all peptide bonds being trans isomers (15, 16). However, the notion that polyprolines constitute a system as well defined in structure as suggested by crystallography has been questioned. Whereas most studies suggested that polyprolines with >3–5 residues form a PPII structure in aqueous solution (19), experimental evidence for significant deviations from this ideal structure was found by ensemble FRET (22), single-molecule FRET (7, 8, 23), and NMR studies (13, 20). Inspired by molecular dynamics simulations, it was suggested that the PPII structure of polyprolines resembles a continuously bend worm-like chain with a persistence length, i.e., the length on which significant bending becomes appreciable, smaller than thought previously (8, 22). On the other hand, theoretical studies predicted reduced end-to-end distances caused by small amounts of interspersed cis isomers (24, 25).

It is known that the amino acid tryptophan (Trp) can efficiently quench the emission of some strongly fluorescent oxazine and rhodamine derivatives either through transient collision or by formation of a nonfluorescent complex that is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions (26, 27). The contact-induced quenching process based on PET requires overlap of fluorophore and quencher molecular orbitals, i.e., van der Waals contact, and thus is sensitive to subnanometer distances (28). Because PET can effectively switch off fluorescence only upon van der Waals contact between fluorophore and Trp, it can be used as a measuring rod probing whether the distance between the two moieties is above or below a critical distance. Related dynamics down to nanosecond time scales can be investigated by analyzing PET interactions using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (PET–FCS) (27, 29–31).

In this work we investigate poly-l-prolines by using contact-induced PET between a site-specifically attached fluorophore (F) and the amino acid Trp: F–(Pro)x–Trp with 0 < x <10. Computational models of polyproline assuming a regular PPII helix demonstrate that for x >6 residues, fluorescence-quenching contact formation between Trp and fluorophore is not possible because of steric separation. In fluorescence experiments, however, we find significant quenching even for constructs where fluorophore and Trp are spaced by >6 residues. To investigate conformational dynamics of polyproline peptides, we analyzed the time evolution of fluorescence quenching by time-resolved spectroscopy and FCS experiments. We found that fluorescence-quenched chain configurations are essentially nonfluorescent on time scales from nano- to milliseconds. Furthermore, we observed considerable steady-state fluorescence changes upon induced prolyl cis/trans isomerization. The observed effects are in agreement with computational models of end-to-end distances of a PPII helix distorted by cis-prolyl isomers.

Results and Discussion

Steady-State Fluorescence Quenching Experiments of Polyproline Conjugates.

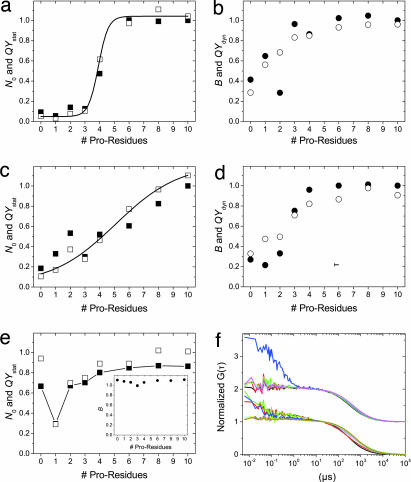

We investigated F–(Pro)x–Trp conjugates with three different fluorophores F (MR121, MR113, and R6G) and 0 < x <10 by using steady-state fluorescence spectroscopy, time-resolved spectroscopy, and FCS (Fig. 1). Steady-state fluorescence measurements revealed a strong dependence of the steady-state quantum yield (QYss, calculated from the fluorescence emission I of the quenched molecule relative to I0 of a nonquenched control sample) on the number of proline residues (Fig. 1). From investigating bimolecular interactions between Trp and various fluorophores, we know that QYss is reduced through static and dynamic quenching processes based on PET between fluorophore and Trp. Static quenching describes formation of efficiently quenched complexes in which fluorophore and Trp favor a stacked configuration that is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions (32). Dynamic quenching takes place during transient diffusional encounters of fluorophore and Trp (26, 30). We could show that fluorescence quenching is dominated by the formation of bimolecular hydrophobic complexes (26). These quenching mechanisms are merely effective upon interaction between fluorophore and Trp, as seen from fluorescence emission of the Trp-missing control sample F–(Pro)6, which exhibits a QYss similar to that of the fluorophore itself.

Fig. 1.

PET quenching interactions in polyprolines: steady-state fluorescence, time-resolve fluorescence, and FCS data for F–(Pro)x–Trp with 0 <x <10 and F being MR121, MR113, and R6G. The number of particles N0 (filled squares) as detected in FCS are shown compared with static ensemble QY (open squares) for polyprolines labeled with MR113 (a), MR121 (c), and R6G (e). Both curves show good agreement in the appearance of an increasing number of completely quenched, stable complexes with a decreasing length of polyprolines. For MR113 (MR121), the transition midpoint is 3.9 (5.1), and the transition width is 0.3 (2.2). For R6G, a QY minimum is detected for constructs with a single Pro residue. Corresponding data for brightness per particle B (filled circles), as measured by FCS, and the dynamic ensemble QY (open circles) are also in good agreement for labels MR113 (b), MR121 (d), and R6G (e Inset). (f) Normalized FCS data are shown for MR113- (upper curves offset by 1) and MR121-labeled polyprolines (lower curves) and reveal the absence of any fluctuations below the diffusion time of ≈1 ms for all but the following samples: MR113–(Pro)2–Trp (blue) and MR121–(Pro)x–Trp with x = 0, 1, or 2 (red, green, blue). However, it should be noted that these fluctuations, as well as dynamic QYs, are detected only for the subpopulations that are not fully quenched because of formation of stable complexes (between 10% and 50% of the total population of the above named samples). The majority of all molecules show no significant fluctuations between 6 ns and the diffusion time ≈1 ms.

Time-resolved fluorescence measurements of F–(Pro)x–Trp conjugates revealed biexponential decays with a main nanosecond component, τ2, and a weak picosecond component, τ1. From the nanosecond lifetime we calculated QYdyn = τ2/τ0 and found the dynamic quenching mechanism to be significant for conjugates with x <4, to decrease monotonically with decreasing x, and to reach a minimum on the order of 30% when F and Trp residue are labeled directly to each other. The weak picosecond component can be attributed to residual fluorescence of inefficiently quenched F–Trp complexes because of deviations from coplanarity (e.g., stacked, side-to-face, or side-to-side interactions) (32).

From steady-state and dynamic quantum yield we calculated the static quantum yield QYstat = QYss / QYdyn, which reflects the formation of essentially nonfluorescent complexes that are quenched on time scales below the ≈50-ps temporal resolution of our time-correlated measurements and thus do not effectively contribute to the measured decay curve. QYstat as a function of the number of Pro residues was found to follow a transition from ≈0.1 to ≈1, where the transition width depends on the fluorophore linker: an oxazine fluorophore connected through a 2-carbon linker (MR113; see structures in Fig. 3) showed a transition with a midpoint at 4 proline residues and a width of <1 residue when fitted to a sigmoidal function; the same oxazine fluorophore connected through a 4-carbon linker (MR121) had a midpoint of 5 and a width of 2 proline residues. For R6G, which has a rigid linker with no unrestricted rotational degree of freedom, the transition was shifted to shorter peptides. These results demonstrate that an interaction between fluorophore and Trp results in efficient quenching, and the width of the transition is determined by the length of the molecular linker and the total degrees of freedom for reorientation of fluorophore and the indole moiety of the Trp.

Fig. 3.

Point clouds representing conformational degrees of freedom for MR121, MR113, R6G, and Trp attached to polyproline. (a) Structure of MR113–(Pro)4–Trp with two coordinate systems defined by N and C termini of the polyproline and translated by vector p. Vectors d and t point to the fluorophore and Trp center of mass, respectively. (b and c) Structure of MR121 (b) and R6G (c). All colored bonds represent rotational degrees of freedom. (d–f) Possible orientations of d and t, relative to an all-trans (Pro)5, are shown for Trp and MR113 (d), MR121 (f), and R6G (g). (e) The influence of a single cis-prolyl isomer on the minimal distance between fluorophore and Trp is shown. All structures are available as a pdb file in supporting information (SI) Appendix.

Although through-bond PET has been observed in polyprolines separating strong organic donors and acceptors (33–36), any significant contribution in these experiments can be ruled out by the observation of ≈100% QY for the R6G–Trp conjugate (in which intramolecular complex formation is prevented by the short and stiff linker), the use of saturated alkyl chains as fluorophore linker, and the steep sigmoidal distance dependence observed for MR113–Trp conjugates.

Conformational Dynamics of Polyprolines Analyzed by FCS.

Because up to 90% of all F–Trp pairs in short polyprolines form nonfluorescent complexes, we used FCS to investigate further the underlying kinetics of complex formation and hence to probe conformational dynamics of the polypeptides. An FCS measurement, as presented in Fig. 1f, yields characteristic parameters for all independent processes that result in fluctuations of the detected fluorescence signal. One such process is translational diffusion of fluorescent molecules through the observation volume. We found a characteristic time constant for this process τD on the order of 500 μs. Any additional independent stochastic process that results in fluctuations on the nanosecond to millisecond time scale would appear as an additive part as shown previously for various quenching interactions (29–31, 37).

In Fig. 1 we present FCS results for F–(Pro)x–Trp samples with F being MR121, MR113, or R6G, and x = (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 10), corresponding to the ensemble measurements discussed above. First, we estimated the relative occupancy N0, i.e., the average number of fluorescent molecules inside the observation volume normalized to the absolute sample concentration (estimated from the optical density measured at the absorption maximum of the fluorophore). We observed a strong decrease of N0 with a decreasing number of Pro residues, which is in excellent agreement with the amount of static quenching as estimated in ensemble measurements. The measurements reveal that static quenching is caused by formation of nonfluorescent complexes that are stable for more than ≈1 ms because no association/dissociation kinetics contribute to the correlation curve and increase the overall amplitude.

Collisional quenching, on the other hand, decreases only the dynamic quantum yield without causing molecules to be switched off for extended periods of time (no influence on N0) but resulting in a reduction of the brightness per molecule B. Fig. 1 b, d, and e indeed shows very good agreement of QYdyn from time-resolved fluorescence measurements and B from FCS experiments for all samples.

The most striking result from FCS measurements is the absence of any fluctuation on time scales between 6 ns (limited by the temporal resolution of the FCS setup) and ≈1 ms (limited by the molecule diffusion time through the observation volume) for most samples. In particular, we found no fluctuations for nearly all samples with the exception of MR113–(Pro)2–Trp, and MR121-(Pro)x-Trp with x = 0, 1, 2. Correlation data for polyprolines labeled with R6G is not presented because R6G exhibits strong intersystem crossing resulting in a correlation decay on the microsecond time scale that could not be distinguished from complex formation kinetics.

These results demonstrate that quenched complexes form, and thus proline conformations exist that are stable for time periods longer than the diffusion time (>1 ms). It is important to remember that dynamic quenching is too fast to be reflected in FCS data (<6 ns) and that fast fluctuations, as e.g., detected for MR113–(Pro)2–Trp, originate only from those molecules that are represented by the overall FCS amplitude. For MR113–(Pro)2–Trp, N0 amounts to ≈10% of the total sample concentration, meaning that the additional fast correlation component originates from only this subpopulation and likely represents sterically unfavorable encounters between fluorophore and Trp. In other words, even though some samples show fast correlation components representing fluctuations of the quenching efficiency on the microsecond time scale, the majority of complexes, once they are formed, are stable for an extended period that is longer than our observation time (≈1 ms).

This observation is in contrast to complex formation as observed in flexible glycine/serine peptides (30) and a polyproline peptide with 2 glycine residues incorporated [MR121–(Pro)3–(Gly)2–(Pro)3–Trp; S.D., H.N., and M.S., unpublished data]. Because Gly is known to introduce considerable flexibility in a polypeptide chain (38–40), both molecules are highly dynamic and reveal a strong nanosecond decay representing complex formation and dissociation as mediated by conformational dynamics of the peptide chain (30). FCS data all yield constant N0 equal to an unquenched control sample, indicating that complexes are never stabilized longer than the diffusion time ≈1 ms.

Prolyl Isomerization.

It is well known that peptide prolyl bonds can undergo cis/trans isomerization. Because characteristic time scales for prolyl isomerization were found to range from ten to hundreds of seconds at room temperature (21, 41), resulting from an energy barrier of ≈80 kJ/mol, it is known to be one of the rate-limiting conformational changes in slowly folding proteins (42, 43). The probability distribution for prolyl bonds to be in the cis/trans conformation was found to be affected by neighboring amino acids (41, 44), the solvent (45), pH, and ionic strength (46). The probability for a cis isomer is on the order of 10% in heterogeneous peptide sequences in physiological buffer as well as in native proteins (43). For smaller oligoprolines, the probability for a cis isomer might be considerably larger (19, 47).

To test the effect of prolyl isomerization on end-to-end distances in polyprolines, we prepared MR121–(Pro)6–Trp conjugates and lyophilized and dissolved them water-free in tetrafluorethanol with 400 mM LiCl (TFE/LiCl). It has been found that the probability for cis isomers is increased in TFE/LiCl reaching values between 40 and 70% depending on the residual water content (45). By monitoring the fluorescence emission after rapid dilution of organic MR121–(Pro)6–Trp solutions in aqueous buffer (final LiCl/TFE content <1%), we found a multiexponential signal increase with characteristic time constants on the order of minutes (at room temperature), in good agreement with time constants for prolyl isomerization observed by other methods (21, 41) (Fig. 2). A multiexponential curve is expected because isomerization in multiple prolyl bonds constitutes the observed conformational change. As control peptides that do not undergo prolyl isomerization we used MR121–Trp and MR121–(GS)x–Trp; as a control peptide that does not undergo fluorescence quenching by PET we used MR121–(Pro)6 without Trp. All control experiments displayed constant fluorescence emission after the required mixing time of a few seconds. It is thus proven that, first, quenching interactions, if sterically allowed, retain their efficiency immediately upon solvent exchange, and second, the unquenched fluorophore emission does not change after initial dilution. Overall, the increase in QYss for Pro-containing peptides over a few hundred seconds demonstrates that prolyl isomerization leads to an increase of the overall end-to-end distance by isomerization of one or multiple prolyl bonds from cis to trans, as suggested by theory (24, 25).

Fig. 2.

Prolyl isomerization monitored by changes of PET-quenching efficiency. Steady-state QY for MR121–(Pro)6–Trp, MR121 (Inset, top curve), MR121–Trp (Inset, bottom curve), and MR121–(GS)3–Trp (Inset, middle curve) is measured upon solvent exchange from LiCl/TFE (promoting cis isomers) to aqueous solution (promoting trans isomers). The steady-state QY increases exponentially with characteristic time constants on the order of minutes for polyprolines; it remains constant for all control samples that lack a prolyl bond.

As further evidence for this conclusion, we performed a second set of experiments showing that prolyl isomerization is equally well observed by FRET. We prepared A–Gly–(Pro)20–Cys–D labeled with various FRET fluorophore pairs (Atto 488 or TMR as D; Alexa 647 or Atto 647N as A) and observed both D and A fluorescence upon solvent exchange (preparation as described above, data not shown). All measurements confirmed the increase in end-to-end distance by a significant decrease in FRET efficiency upon solvent exchange. The characteristic time constants were independent of fluorophore pairs and comparable with those observed in PET experiments. A precise analysis of FRET efficiencies was complicated because contact-induced quenching processes between D and A also contribute to the observed signal changes. This observation again suggests that cis conformations allow both ends of polyprolines to come close enough for electronic interactions between donor and acceptor, resulting in nonradiative relaxation pathways. It should be noted that so far all FRET studies on polyprolines used organic reporter groups that exhibit the tendency to form hydrophobic complexes upon contact formation and that static fluorescence quenching caused by contact-induced complex formation for FRET pairs has been reported elsewhere (22).

Simulations.

To elucidate the influence of prolyl isomerization on end-to-end distances in polyprolines, we set up molecular structures of the experimentally investigated constructs by using molecular mechanics force fields and modeled energetically allowed structures with various distributions of trans/cis bonds. We found a strong influence of the amount and position of individual cis bonds on end-to-end distances. To mimic experiments, we determined the minimal distances dmin between fluorophore (MR113, MR121, and R6G; attached at the N terminus) and Trp (last residue of the polypeptide) in conformations that are sterically allowed for each given polyproline structure.

Polyproline structures were determined from an ideal all-trans PPII helix, as predicted from crystal structure (15) with individual prolyl bonds forced into a cis conformation. Energy minimization yielded an energetically acceptable polyproline conformer with distorted PPII structure. Minimal distances between fluorophore and Trp residue, which can be used to assess whether contact-induced quenching interactions are feasible or not, were determined by analyzing the conformational space of fluorophore/linker and Trp residue. Sampling the rotational degrees of freedom for all bonds linking the planar fluorophore to the peptide backbone (and correspondingly those linking the planar indole moiety to the peptide backbone), and excluding those conformations that lead to steric clashes within the whole structure, we built point clouds representing the allowed center of mass positions for fluorophore and indole moieties.

In Fig. 3 sterically allowed conformations are shown for MR113, MR121, R6G, and Trp attached to a polyproline in a PPII helical conformation, illustrating the conformational space that can be populated by fluorophore and Trp. It is obvious that MR121 with 4 rotational degrees of freedom in the 4-carbon linker samples the largest conformational space. MR113 and R6G, with 2 and 0 rotational degrees of freedom, respectively, are more restricted.

We define dmin as the minimal distance between the fluorophore and Trp center of mass for any two given point clouds. Determination of dmin for points separated by the various polyproline structures allows us to assess in a conservative manner whether fluorescence quenching is, in principle, possible or not. In Fig. 4 a we plotted dmin for a series of polyprolines MR113–(Pro)x–Trp (with 2 < x < 20 residues) with single cis bonds at the indicated position in the proline chain. dmin for MR113/Trp is 0.2–0.3 nm smaller than for MR121/Trp in a PPII helix. This difference is in agreement with the length dependence of the experimental fluorescence quantum yield showing a transition for MR113 that is shifted by about 1 proline residue (helical rise in PPII helix is 0.3 nm) compared with MR121. Apparently, dmin changes dramatically upon introduction of a single cis isomer, in particular when positioned at the center of the proline chain. A PET quenching interaction becomes feasible when fluorophore and Trp are at van der Waals contact, which has been estimated to occur for dmin between 0.5 nm and 1.0 nm (32) (indicated by the dotted lines in Fig. 4b). The data in Fig. 4a cannot prove that PET quenching does occur in structures with dmin below a certain threshold. However, it can predict structures in which PET quenching is strictly prohibited.

Fig. 4.

Minimal distances dmin between fluorophore and Trp in polyprolines with a single cis isomer. (a) The conformational space for MR113 and Trp is sampled, the closest approach identified, and dmin is estimated for MR113–(Pro)x–Trp with x = (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, and 20) (indicated by the length of data curve). All prolyl bonds are in the trans conformation except for a single cis isomer located at the indicated position (counted from the N terminus). The first data point at position 0 represents the all-trans conformation. (b) For each polyproline with x number of residues and a single cis isomer, the configuration that allows closest approach between fluorophore and Trp is identified (i.e., the minimum for each polyproline in a) and dmin displayed. The following structures were investigated with either MR113 (red squares), MR121 (blue circles), or R6G (black triangles) attached: energy-minimized polyproline helix with all bonds in trans conformation (open symbols); energy minimized structures with a single cis bond as shown in a (closed symbols). The black line represents end-to-end distances of a PPII helix as defined from the crystal structure (15) (black line). The dotted lines indicate the distance range above which no quenching interactions are possible.

The computational results demonstrate that prolyl trans/cis isomerization allows contact formation between fluorophore and Trp in longer polyprolines than would be possible in all-trans PPII configuration where both moieties are well separated. This result further explains why PET quenching is sensitive to prolyl isomerization as shown in experiments discussed above and suggests that, given the non-zero probability of prolyl cis isomers, average end-to-end distances in a polyproline ensemble should be significantly smaller than expected for a pure PPII structure. Because the rate of prolyl isomerization was estimated to be on a minute time scale, the populations of various isomers form an equilibrium distribution that does not change significantly during the ensemble and FCS experiments in aqueous solution discussed above.

The experimental QYs reveal PET quenching interactions in F–(Pro)x–Trp with x < 8 (for MR121), x < 5 (for MR113), and x < 4 (for R6G). Therefore, the calculations suggest that the experimental results are not consistent with a regular polyproline PPII helix but can be explained by distorted structure caused by interspersed cis-prolyl isomers. It is important to remember that the formation of hydrophobic complexes between fluorophore and Trp is a short-range interaction and such complexes might influence the cis/trans equilibrium distribution in labeled polyprolines. However, it reliably indicates that end-to-end distances can be reduced by cis isomerization to an extend that contact between end groups is possible, and thus polyprolines do not behave as rigid rods.

Conclusion

Deviations between theoretical end-to-end distances for polyprolines and experimental ones as estimated from FRET efficiencies have been a topic of ongoing discussion (7, 8, 22). Theoretical studies based on Langevin simulations combined with FRET experiments suggested continuous bending resembling a worm-like chain behavior (8). On the other hand, interspersed cis/trans isomers have been suggested previously as the source of reduced end-to-end distances (7, 24, 25). However, no experimental evidence for strong heterogeneity in polyprolines has been given yet. Average FRET efficiencies from polyproline samples were only analyzed by comparison with a worm-like chain model, and an apparent persistence length between 2 and 4 nm has been estimated (7, 8, 22).

Indeed, the present results suggest that subpopulations in polyproline samples containing cis-prolyl isomers significantly reduce the average end-to-end distance of the chain. This result is in good agreement with a series of experimental, theoretical, and computational studies on longer polyprolines (13, 24, 25). Considering the nanosecond time scales that have been observed for end-to-end contact rates of unstructured, highly flexible poly-(Gly-Ser) peptides (30, 48), any dynamics that result in end-to-end distance changes large enough to be detected by FRET or PET should be slower than nanoseconds and faster than ≈1 ms (the observation limits in our FCS experiment) and would therefore have been detected in FCS experiments. However, no such fluctuations were detected either here by PET-FCS or recently by correlation of FRET efficiencies (49).

The emerging picture that polyprolines present a static entity on time scales from nano- to milliseconds and nanometer length scales, comprising static structural heterogeneity caused by prolyl cis/trans isomerization, makes any comparison with a continuous worm-like chain model difficult. The present work suggests that for the use of polyprolines as a molecular ruler, for instance to calibrate FRET efficiency measurements, an accurate determination of the probability for a cis isomer as function of proline length, position, and total number of cis isomers is indispensable.

Materials and Methods

Peptide Conjugates.

Synthetic peptides with the sequence (Pro)x–Trp (x = 0–10) were purchased from Thermo (Ulm, Germany). Polypeptides were modified with the amino-reactive oxazine fluorophores MR121-NHS, MR113-NHS (provided by K. H. Drexhage, Universität Siegen, Germany), and the rhodamine derivative R6G-NHS (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) at the N terminus by using classical N-hydroxysuccinimidylester (NHS-ester) chemistry. Fifty micrograms of reactive fluorophore was dissolved in 5 μl of acetonitrile. Approximately 500 μg of peptide was dissolved in 50 μl of aqueous sodium bicarbonate (50 mM, pH 8.3) containing 30% (vol/vol) acetonitrile. Fluorophore and peptide solutions were mixed and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Labeled peptide conjugates were purified by reversed-phase (Hypersil-ODS C18 column) HPLC (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) by using a linear gradient of 0–75% acetonitrile in 0.1 M aqueous triethylammonium acetate.

Ensemble Spectroscopy.

Absorption and steady-state emission measurements were carried out on a UV-visible (Lambda 25; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) or fluorescence spectrometer (Cary Eclipse; Varian, Darmstadt, Germany) at 20°C. Fluorescence lifetimes were measured by time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) at 20°C under the magic angle (54.7°) with a standard TCSPC spectrometer (model 5000MC; IBH, Glasgow, U.K.) equipped with a pulsed laser diode (635 nm). In all cases a biexponential model I = I0(a1τ1 + a2τ2) was adequate to describe the measured decay, where ai are preexponential factors that describe the ratio of the excited species and τi denote their lifetimes. Because of the limited time resolution, strongly quenched populations with decay times shorter than ≈50 ps were not revealed. Molecular aggregation, glass absorption of peptides or fluorophores, and reabsorption of emitted photons were excluded in all ensemble experiments by concentration-independent results up to ≈1 μM. The steady-state (QYss = I/I0) and dynamic (QYdyn = τ2/τ0) quantum yield were calculated from fluorescence intensity I and lifetime τ2, where τ0 and I0 are the fluorescence lifetime and intensity of a nonquenched reference sample, respectively. The steady-state quantum yield is the product of static and dynamic quantum yield (QYss = QYstat × QYdyn), where QYdyn reflects collisional quenching and QYstat reflects formation of nonfluorescent complexes (26).

FCS.

FCS experiments were performed on a confocal fluorescence microscope as described previously (29). Fluorescently modified peptides were diluted to a final concentration of ≈0.5 nM in PBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.3 mg/ml BSA and 0.05% Tween 20 to suppress glass surface interactions. Excitation intensities were adjusted to 1 mW (at the back aperture of the objective) for measuring submicrosecond kinetics and reduced to 50 μW, avoiding possible artifacts caused by photobleaching and fluorescence saturation of the fluorophore, for determination of sample concentrations. Fluctuations in the fluorescence signal I(t) were analyzed by the second-order autocorrelation function. For simple diffusion, the correlation function can be described by two parameters, the occupancy of the observation volume N and the characteristic diffusion time τD (50, 51). For each FCS measurement, we calculated a relative occupancy N0 by normalizing N to the absolute molecule concentration (as determined from optical density at the fluorophore absorption maximum). Dividing the average fluorescence signal I by N we further calculated B, the average photon emission rate per individual molecule.

Prolyl Isomerization.

Polyprolines with a high content of peptide bonds in the cis conformation were prepared by dissolving lyophilized peptides in anhydrous 2,2,2-trifluorethanol (TFE) with 400 mM LiCl. We observed kinetics of prolyl isomerization in a mixing experiment by diluting 10 μl of TFE/LiCl solution with ≈100 μM MR121–(Pro)x–Trp in 1 ml of PBS (pH 7.4, containing 0.3 mg/ml BSA and 0.05% Tween 20 to suppress glass surface interactions) and immediately recording fluorescence emission over time.

Simulations.

Point clouds resembling all sterically possible positions of the nonproline moiety aromatic system center relative to the connecting amide bond were generated for model structures F–(Pro)10 (F = MR113, MR121, R6G) and (Pro)10–Trp. The rotatable dihedral angles (as highlighted in Fig. 3) were sampled in steps of 5°, 20°, 2°, and 10° for MR113, MR121, R6G, and Trp, respectively. Standard residue conformations from AMBER 8 (52) were used for amino acids; fluorophore structures were derived through ab initio calculations (see SI Appendix). The resulting point clouds were reduced to 1,680 data points by grouping points with similar angular alignment (see SI Appendix). Molecular mechanics simulations were carried out for Gly–(Pro)x–Gly (x = 1–6, 8, 10, 12, 15, and 20) in all-trans and all possible mono-cis conformations. Structures were generated from AMBER standard libraries and energy minimized with the Duan et al. force field (53) (maximum 200,000 steps, DRMS = 10−4, NB cutoff = 0.12 nm, GB implicit solvent with 200 mM NaCl). N- and C-terminal glycine residues were then replaced by fluorophore and Trp point clouds, respectively, and structures that resulted in steric clashes between fluorophore/Trp and the polyproline were eliminated (see SI Appendix). Upon combination of point cloud data and polyproline structure the minimal distance between the fluorophore and Trp aromatic center was investigated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. K. H. Drexhage (Universität Siegen, Germany) for MR121 and MR113 and Andrea Vaiana for discussion and helpful comments on computer simulations. The work was funded by the German Research Foundation Grants DFG SA289/1 and SFB 613.

Abbreviations

- F

fluorophore

- FCS

fluorescence correlation spectroscopy

- FRET

Förster resonance energy transfer

- NHS

N-hydroxysuccinimidyl

- PET

photoinduced electron transfer

- PPII

polyproline type II

- QY

quantum yield.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0705605104/DC1.

References

- 1.Stryer L, Haugland RP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;58:719–726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.2.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Förster T. Ann Physik. 1948;6:55–75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selvin PR. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:730–734. doi: 10.1038/78948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deniz AA, Dahan M, Grunwell JR, Ha T, Faulhaber AE, Chemla DS, Weiss S, Schultz PG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3670–3675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ha T. Methods. 2001;25:78–86. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kapanidis AN, Lee NK, Laurence TA, Doose S, Margeat E, Weiss S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8936–8941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401690101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watkins LP, Chang H, Yang H. J Phys Chem A. 2006;110:5191–5203. doi: 10.1021/jp055886d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuler B, Lipman EA, Steinbach PJ, Kumke M, Eaton WA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2754–2759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408164102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nir E, Michalet X, Hamadani KM, Laurence TA, Neuhauser D, Kovchegov Y, Weiss S. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:22103–22124. doi: 10.1021/jp063483n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antonik M, Felekyan S, Gaiduk A, Seidel CA. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:6970–6978. doi: 10.1021/jp057257+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee NK, Kapanidis AN, Wang Y, Michalet X, Mukhopadhyay J, Ebright RH, Weiss S. Biophys J. 2005;88:2939–2953. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.054114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schimmel PR, Flory PJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;58:52–59. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu CC, Komoroski RA, Mandelkern L. Macromolecules. 1975;8:635–637. doi: 10.1021/ma60047a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Traub W, Shmueli U. Nature. 1963;198:1165–1166. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cowan PM, McGavin S. Nature. 1955;176:501–503. doi: 10.1038/1761062a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinberg IZ, Harrington WF, Berger A, Sela M, Katchalski E. J Am Chem Soc. 1960;82:5263–5279. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isemura T, Okabayashi H, Sakakibara S. Biopolymers. 1968;6:307–321. doi: 10.1002/bip.1968.360060306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okabayashi H, Isemura T, Sakakibara S. Biopolymers. 1968;6:323–330. doi: 10.1002/bip.1968.360060307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helbecque N, Loucheux-Lefebvre MH. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1982;19:94–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1982.tb03028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacob J, Baker B, Bryant RG, Cafiso DS. Biophys J. 1999;77:1086–1092. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76958-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grathwohl C, Wuthrich K. Biopolymers. 1981;20:2623–2633. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sahoo H, Roccatano D, Hennig A, Nau WM. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9762–9772. doi: 10.1021/ja072178s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schuler B, Lipman EA, Eaton WA. Nature. 2002;419:743–747. doi: 10.1038/nature01060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mattice WL, Mandelkern L. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:1769–1777. doi: 10.1021/ja00736a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka S, Scheraga HA. Macromolecules. 1975;8:623–631. doi: 10.1021/ma60047a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doose S, Neuweiler H, Sauer M. Chemphyschem. 2005;6:2277–2285. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200500191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neuweiler H, Sauer M. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2004;5:285–298. doi: 10.2174/1389201043376896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang H, Luo G, Karnchanaphanurach P, Louie TM, Rech I, Cova S, Xun L, Xie XS. Science. 2003;302:262–266. doi: 10.1126/science.1086911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neuweiler H, Doose S, Sauer M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16650–16655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507351102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neuweiler H, Lollmann M, Doose S, Sauer M. J Mol Biol. 2006;365:856–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim J, Doose S, Neuweiler H, Sauer M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2516–2527. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaiana AC, Neuweiler H, Schulz A, Wolfrum J, Sauer M, Smith JC. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14564–14572. doi: 10.1021/ja036082j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mishra AK, Chandrasekar R, Faraggi M, Klapper MH. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:1414–1422. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Defelippis MR, Faraggi M, Klapper MH. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:5640–5642. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isied SS, Vassilian A. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:1732–1736. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gray HB, Winkler JR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3534–3539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408029102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chattopadhyay K, Elson EL, Frieden C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2385–2389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500127102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang F, Nau WM. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:2269–2272. doi: 10.1002/anie.200250684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krieger F, Moglich A, Kiefhaber T. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3346–3352. doi: 10.1021/ja042798i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brant DA, Flory PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:2791–2800. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reimer U, Scherer G, Drewello M, Kruber S, Schutkowski M, Fischer G. J Mol Biol. 1998;279:449–460. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brandts JF, Halvorson HR, Brennan M. Biochemistry. 1975;14:4953–4963. doi: 10.1021/bi00693a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmid FX. In: Protein Folding Handbook. Buchner J, Kiefhaber T, editors. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley; 2005. pp. 916–945. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grathwohl C, Wuthrich K. Biopolymers. 1976;15:2025–2041. doi: 10.1002/bip.1976.360151012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kofron JL, Kuzmic P, Kishore V, Colon-Bonilla E, Rich DH. Biochemistry. 1991;30:6127–6134. doi: 10.1021/bi00239a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grathwohl C, Wuthrich K. Biopolymers. 1976;15:2043–2057. doi: 10.1002/bip.1976.360151013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chao YYH, Bersohn R. Biopolymers. 1978;17:2761–2767. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krieger F, Fierz B, Bieri O, Drewello M, Kiefhaber T. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:265–274. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00892-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nettels D, Gopich IV, Hoffmann A, Schuler B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2655–2660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611093104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Magde D, Elson EL, Webb WW. Biopolymers. 1974;13:29–61. doi: 10.1002/bip.1974.360130103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hess ST, Huang S, Heikal AA, Webb WW. Biochemistry. 2002;41:697–705. doi: 10.1021/bi0118512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pearlman DA, Case DA, Caldwell JW, Ross WS, Cheatham TE, III, DeBolt S, Freguson D, Sebel G, Kollman P. Comput Physics Commun. 1995;91:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duan Y, Wu C, Chowdhury S, Lee MC, Xiong G, Zhang W, Yang R, Cieplak P, Luo R, Lee T, et al. J Comp Chem. 2003;24:1999–2012. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.