Abstract

Evidence from 3 experiments reveals interference effects from structural relationships that are inconsistent with any grammatical parse of the perceived input. Processing disruption was observed when items occurring between a head and a dependent overlapped with either (or both) syntactic or semantic features of the dependent. Effects of syntactic interference occur in the earliest online measures in the region where the retrieval of a long-distance dependent occurs. Semantic interference effects occur in later online measures at the end of the sentence. Both effects endure in offline comprehension measures, suggesting that interfering items participate in incorrect interpretations that resist reanalysis. The data are discussed in terms of a cue-based retrieval account of parsing, which reconciles the fact that the parser must violate the grammar in order for these interference effects to occur. Broader implications of this research indicate a need for a precise specification of the interface between the parsing mechanism and the memory system that supports language comprehension.

Keywords: cue-based memory retrieval, interference, complexity effects, sentence processing, constraint-based parsing

Interference effects in sentence processing are beginning to be recognized, but the conditions that give rise to these effects are not well understood (Gordon, Hendrick, & Johnson, 2001, 2004; Van Dyke & Lewis, 2003; Van Dyke & McElree, 2006). Gordon and colleagues (2001, 2004) observed that the classic processing advantage for subject-relative clauses over object-relative clauses was reduced or eliminated when the second noun phrase (NP) in sentences such as 1a and 1b was either a pronoun (you or everyone) or a proper name (Joe). They attributed their result to a reduction in similarity-based interference that occurs when the two NPs have different referential characteristics (i.e., common NPs refer via their description; pronouns and proper names refer directly to objects previously established in the discourse). Thus, on this account, interference effects are due to the presence of NPs with shared referential characteristics.

(1a) The banker that praised [the barber/a barber/Joe/you/everyone] climbed the mountain.

(1b) The banker that [the barber/a barber/Joe/you/everyone] praised climbed the mountain.

Several researchers have suggested an alternative account, one that implicates retrieval as the source of interference effects (Lewis, Vasishth, & Van Dyke, 2006; McElree, Foraker, & Dyer, 2003; Van Dyke, 2002; Van Dyke & Lewis, 2003; Van Dyke & McElree, 2006). Although these are not the first sentence-processing theories to include a retrieval component, previous theories (e.g., Gibson, 1998, 2000) have emphasized decay as the source of processing complexity, on the basis of hypothesized memory demands that certain structures present for comprehenders. In contrast, approaches that focus on interference as the primary determinant of complexity have drawn on specific retrieval mechanisms whose properties have been well studied in the memory literature. According to these theories, grammatical relations are created via cue-based retrieval of necessary constituents. Grammatical heads provide retrieval cues that identify necessary properties of the required constituent (e.g., grammatical case, thematic role, semantic properties), which are then combined in parallel, to create a single retrieval probe. One formalization of this idea is given in Equation 1, where the probability, P, of retrieving a particular item, Ii, to serve as the dependent of the cuing constituent is defined as the strength of the association, S, between each feature of the probe (Q1, …, Qm), and the features of the actual memory trace (I1, …, In), denoted as S(Qj,Ii)wj, where wj is a weighting factor denoting the relative saliency of the different cues.

| (1) |

This equation was borrowed from mathematical models of memory retrieval (especially Gillund & Shiffrin, 1984; see also Hintzman, 1984, 1988; Nairne, 1990; Raaijmakers & Shiffrin, 1981) and is consistent with the adaptive control of thought—rational (ACT–R) computational model (cf. Lewis & Vasishth, 2005, for an ACT–R model of cue-based parsing). It is based on a large body of experimental data showing that memory retrieval depends both on the match between the retrieval probe and the retrieval target, as well as the match between the retrieval probe and all other items in memory. Specifically, it states that the probability of retrieving a particular item with a given retrieval probe is an increasing function of the probe-to-item strength and a decreasing function of the sum of the probe-to-item strengths for all other items stored in memory. Thus, similarity-based interference arises in the presence of one or more distractor items that are very similar to the target item vis-à-vis the retrieval probe, because its probe-to-item strength will be highly similar to the probe-to-target strength.

This framework offers a general explanation of interference effects arising both from the presence of similar items in memory, as suggested by the Gordon et al. (2001, 2004) data, and from ambiguous retrieval cues. In the former case, a common noun distractor that overlaps with many of the properties of the target noun (including grammatical, semantic, or referential) will increase the value of the denominator in Equation 1 as compared with when there is less overlap of a distractor with the target, as may be the case with a pronoun or proper noun distractor, whose semantic and referential properties may distinguish it from the target. This will make the probability of retrieving the target greater when there is a pronoun or proper name distractor (which supplies less interference) than when there is a common noun distractor, despite the fact that the retrieval cues (and hence the numerator) remain constant in the two cases.

Direct evidence in support of the effect of ambiguous retrieval cues was presented by Van Dyke and McElree (2006), who manipulated the probe-to-item match between the target item and its distractors. Using a memory load paradigm, where participants had to memorize a list of three words prior to reading a sentence, they compared conditions as in Sentence 2a, where the only NP to fit the semantic requirements for the object of the verb sailed is boat, and conditions as in Sentence 2b, where any of the NPs in memory (i.e., table, sink, truck, boat) could serve as the object of fixed.

-

(2a) TABLE–SINK–TRUCK

It was the boat that the guy who lived by the sea sailed in two sunny days.

-

(2b) TABLE–SINK–TRUCK

It was the boat that the guy who lived by the sea fixed in two sunny days.

The authors observed increased reading times at the manipulated verb for the interfering conditions like in Sentence 2b, an effect that disappeared when participants read these sentences without having to first memorize the distractor items. These results clearly implicate the role of retrieval, arising from retrieval cues that do not uniquely identify the object of fixed when there are other fixable items in memory, causing a reduction of the numerator in Equation 1 despite identical distractors across the two conditions. Notably, the referential similarity account presented by Gordon and colleagues (2001, 2004) cannot explain these effects, because the referential properties of the distractor items are identical (i.e., all descriptive NPs).

Additional evidence for the centrality of retrieval was provided by Van Dyke and Lewis (2003), who compared sentences such as 3a and 3b, in which a distracting NP intervenes between a long-distance subject–verb dependency. In these sentences, the retrieval probe comes from the phrase was complaining, in which the long-distance subject resident must be retrieved despite a more recent NP (warehouse). Increased reading times were observed in Sentence 3b as compared with Sentence 3a, despite intervening regions of the same length. Van Dyke and Lewis characterized 3b as a sentence containing syntactic interference, after the type of retrieval cue matching the distractor. Thus, in 3b, where the intervening NP is a grammatical subject, interference is produced by the match with the retrieval cues of was complaining, which is looking for its subject. In contrast, the intervening NP in 3a is the object of a preposition and hence does not match the subject cues of the verb.

(3a) The worker was surprised that the resident who was living near the dangerous warehouse was complaining about the investigation.

(3b) The worker was surprised that the resident who said that the warehouse was dangerous was complaining about the investigation.

The current experiments extend the approach of investigating interference produced by specific types of retrieval cues. Specifically, the role of semantic interference was examined, to determine whether items that fit the semantic retrieval cues from the retrieval probe could create difficulty. The evidence from Van Dyke and McElree (2006) described above suggests that they can; however, these effects were observed in the absence of any grammatical marking on the distracting items. If syntactic properties play a primary role in determining a sentence’s interpretation, as proposed by syntax-first parsing models (Ferreira & Clifton, 1986; Frazier, 1978, 1990; Frazier & Rayner, 1982), then we may expect that semantic interference would not occur when the syntactic properties of the distracting items do not fit the syntactic retrieval cues from the retrieval probe. Thus, in a variation of Sentence 3a, given in Sentence 4, where the intervening NP neighbor fits the semantic cues of the verb was complaining, the semantic match of the NP is not predicted to create difficulty because neighbor is grammatically unavailable—it has already been assigned case marking as the object of a preposition and hence does not match the syntactic cues from was complaining, which is looking for a subject.

(4) The worker was surprised that the resident who was living near the dangerous neighbor was complaining about the investigation.

Evidence that semantic interference would occur has been observed by Tabor, Galantucci, and Richardson (2004), who demonstrated effects of local coherence in processing reduced relative clauses over and above the difficulty associated with processing the reduction itself. In particular, they found that Sentence 5a produced slower reading times and reduced grammaticality judgments as compared with its unreduced control than Sentence 5b when compared with an analogous unreduced control (local coherence shown in italics).

(5a) The coach smiled at the player tossed a Frisbee by the opposing team.

(5b) The coach smiled at the player thrown a Frisbee by the opposing team.

The authors interpreted their results as support for a constraint–satisfaction approach to parsing in which locally consistent fragments can create competition for the global parse (MacDonald, Pearlmutter, & Seidenberg, 1994; Stevenson, 1994, 1998; Tabor & Hutchins, 2004; Vosse & Kempen, 2000). According to this view, syntactic and semantic factors contribute simultaneously to produce the parse most consistent with the evidence from the input. One contribution of the current study is to provide evidence that these effects are not contingent on adjacency or local coherence. The cue-based retrieval account predicts that semantic interference should also be observed in a sentence like 6, where the distracting NP neighbor is distant from the verb was complaining as well as having no locally coherent grammatical analysis. This is also a prediction of self-organizing constraint–satisfaction models, such as Tabor and Hutchins’ (2004) self-organizing parser (SOPARSE), which has no mechanism for restricting attachments to only adjacent items.

(6) The worker was surprised that the resident who said that the neighbor was dangerous was complaining about the investigation.

Broad effects of semantic interference in sentence processing have been previously observed but have not been investigated systematically using online processing measures. For example, Stolz (1967) observed that participants had more difficulty paraphrasing the clauses of center embedded sentences in which all of the NPs were potential subjects for the embedded verbs, as in 7a, as compared with sentences in which the meaning of the verbs helped to distinguish the more appropriate subject, as in 7b.

(7a) The chef that the waiter that the busboy appreciated teased admired good musicians.

(7b) The bees that the hives that the farmer built housed stung the children.

Similarly, King and Just (1991) found that a manipulation of pragmatic bias of verbs vis-à-vis the NPs in object-relative clauses affected comprehension accuracy for both high- and low-memory-capacity participants. Specifically, they found that participants had more difficulty answering true–false probes about the main clause in sentences like 8a, in which both NPs can serve as subject for the main verb, as compared with 8b, in which the meaning of the verbs can be used to identify the subject of each. King and Just also collected reading times for these sentences, but they reported only a weak effect of pragmatic bias on reading times (.05 < p < .10).

(8a) The robber that the fireman detested watched the program.

(8b) The robber that the fireman rescued stole the jewelry.

The experiments reported here are intended to replicate the syntactic interference effects observed earlier and to test the hypothesis that semantic interference effects will occur whenever a semantically suitable NP occurs in the region intervening between the subject and verb of a long-distance dependency. To accomplish this, I conducted three experiments in which syntactic and semantic interference were crossed in a 2 × 2 design, creating the four conditions in Table 1. The four conditions can be constructed by combining the sentence introduction and conclusion with one of the four intervening regions. To increase readability, I hereafter refer to the low and high syntactic interference conditions (as in Sentences 3a and 3b), respectively, as LoSyn and HiSyn. The low and high semantic interference conditions are called LoSem and HiSem.

Table 1.

Example Syntactic and Semantic Interference Stimuli for Experiment 1 With Regions for Analysis

| Sentence region | Example stimulus |

|---|---|

| Introduction | The worker was surprised that the resident |

| Intervening region | |

| LoSyn/LoSem | who was living near the dangerous warehouse |

| LoSyn/HiSem | who was living near the dangerous neighbor |

| HiSyn/LoSem | who said that the warehouse was dangerous |

| HiSyn/HiSem | who said that the neighbor was dangerous |

| Critical region | was complaining |

| Spillover region | about the |

| Last word | investigation |

Note. LoSyn and HiSyn refer to low and high syntactic interference conditions, respectively; LoSem and HiSem refer to low and high semantic interference conditions, respectively.

The key claim of the retrieval account is that processing difficulty will be encountered whenever the retrieval cues from the verb was complaining do not unambiguously identify its subject. Thus, the HiSyn conditions are expected to be more difficult than the LoSyn conditions because of the intervening subject, which creates syntactic interference by providing a distracting NP with subject marking to match the subject cues from the retrieval probe. Similarly, the HiSem conditions are expected to be more difficult than the LoSem conditions because the intervening NP creates semantic interference due to neighbor being the type of entity that “can complain,” hence matching the semantic cues from the retrieval probe.

These sentences were investigated using two different experimental paradigms: a moving-window paradigm with a “Got it?” task and an eye-tracking paradigm with cloze comprehension questions, which required participants to report the interpretation they had constructed during reading. It is expected that these paradigms will provide converging evidence for the observed effects, as well as yielding increasingly detailed information about how the syntactic and semantic interference effects operate during sentence processing.

Experiment 1: “Got It?” Task

A test of the syntactic and semantic interference effects was conducted using the “Got it?” task (Frazier, Clifton, & Randall, 1983). This task was chosen because it provides an indication of the interpretability of sentences without requiring participants to make explicit decisions about grammaticality, a topic that can cause considerable anxiety in otherwise capable students. In this task, participants are instructed to judge as quickly as possible after the end of a sentence whether they understood it. If the person had no difficulty understanding the sentence, he or she will answer “yes.” A “no” answer indicates that the person was unable to make sense of the sentence, perhaps owing to difficulty completing the long-distance attachment. It is important to note that participants are encouraged not to attempt to make sense of an awkward sentence, which means that this task allows an estimate of the immediate effects of retrieval interference, prior to any deliberate attempts to make sense of the sentence.

Method

Participants

Thirty-five students from the University of Pittsburgh participated in the experiment in exchange for partial course credit. All participants were native speakers of American English.

Materials

Forty-eight sets of experimental items were randomly chosen from the piloted set (described below) for use in Experiment 1. Four lists of items were constructed so that each participant received one of the four conditions from each set of items but no participant saw more than one condition in each set. Each participant received sentences in each of the four conditions, permitting a within-subject analysis of the data. Items were presented in a blocked random order such that every experimental item was separated from the next experimental item by three filler items of different syntactic constructions.

The filler items were designed to be appropriate matches for several aspects of the experimental sentences. To match the structures of our interfering items, in half of the filler items we used subject-relative clauses as objects (e.g., The informed citizen elected the candidate who spoke in Arkansas and Pennsylvania). Thus, the direct object of these sentences was similar to the objects in our low-interference items except that there was no long-distance attachment required. Of the other half, two thirds were simple transitive sentences with adjective- and/or preposition-modified subjects and preposition-modified objects (e.g., The large hospital with budget problems fired the doctor with the least experience). The last sixth of the fillers were multiple clause transitive sentences designed to be long (e.g., The ski-instructor warned the students of the icy conditions but that didn’t prevent them from taking to the slope anyway). These items were included to discourage participants from focusing on length as indicating a hard-to-comprehend sentence.

After this set of 144 filler items was constructed, half of the items were made ungrammatical via the addition of one or two words at random points in the sentences (e.g., The friendly manager encouraged the employees earn with sizeable bonuses). These items were included in order to maintain participants’ vigilance in the “Got it?” task.

Piloting

The semantic interference conditions required piloting to ensure that the intervening noun could serve as a plausible subject for the final verb phrase. This involved transforming the semantic interference sentences into the three conditions presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sentences for Semantic Interference Pilot

| Condition | Sentence |

|---|---|

| Target | The worker was surprised that the resident was complaining about the investigation. |

| Implausible distractor | The worker was surprised that the warehouse was complaining about the investigation. |

| Plausible distractor | The worker was surprised that the neighbor was complaining about the investigation. |

These sentences provide an appropriate test of semantic interference because semantic interference occurs only when the cues provided by the final verb match the features of the intervening NP sufficiently well that they could be construed as the subject of that verb. Consequently, if the plausible and target conditions in Table 2 are rated similarly, then we would expect to observe semantic interference when these NP–verb combinations appear in the structures in Table 1. Likewise, for semantic interference to be absent, the implausible condition must be recognized as such and be significantly different from both the plausible and the target condition.

So there would be a sufficient number of high-contrasting experimental items, a pool of 160 item sets were constructed following the paradigm illustrated in Table 1. The three piloting conditions discussed above (shown in Table 2) produced 480 sentences. The full set of 480 sentences was randomized and then divided in half so that any one participant would be required to rate only 240 sentences in a 1-hr testing period. In some cases, two out of the three sentences in a set occurred in the same list, but these did not occur sequentially. The sentences were presented on personal computers using the MEL Professional experimental package (Version 2; Schneider, 1995). Students from the University of Pittsburgh undergraduate psychology subject pool participated in the piloting experiment in exchange for partial course credit. Sixteen participants rated the first half of the stimuli, and 15 different participants rated the second.

Participants were instructed to rate each of the sentences on a 5-point “sensibility” scale (1 = makes no sense, 5 = makes perfect sense). During the experiment, each sentence appeared on the screen in its entirety; participants entered their rating for that sentence and then pressed the space bar to move to the next sentence. Participants had no time pressure and received no feedback in the experiment, and no filler items were included.

Two one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted on each item separately. The first compared the target and plausible distractor conditions, and no significant difference was expected between these two. Fifty-two of the 160 items did produce a significant difference between the two plausible conditions and were either dropped from the set or corrected, if an obvious alternative NP suggested itself. The second ANOVA compared the plausible and the implausible conditions, and we did expect to find a significant difference between these conditions. Five of the 160 item sets did not meet this criterion and were discarded or corrected. All corrected items were piloted with 12 participants in a more informal paper-test format, and all reached the same significance criteria described above except for 10 sets, which were dropped from the pool. The materials for Experiments 1–3 were randomly drawn from the final 150 item sets.

Procedure

As with the pilot experiment, Experiment 1 was implemented in the MEL Professional experimental package (Version 2; Schneider, 1995) and was run on personal computers. The 192 sentences (48 experimental; 144 filler) were presented in a noncumulative, self-paced, moving-window format, where each sentence was presented one word at a time. Prior to the experiment, participants were instructed to answer “yes” or “no” to the question “Did you get it?” Following Frazier et al. (1983), we encouraged them to answer as quickly as possible, without trying to make sense of a sentence that sounded awkward. Participants were warned that some sentences in this experiment were designed to be difficult to understand. A series of six practice sentences were presented prior to the experiment so that participants could familiarize themselves with the keyboard and the presentation sequence.

Design and Analysis

This experiment produced two dependent measures: accuracy for the “Got it?” task and reading times from the self-paced presentation. Both measures were analyzed via a 2 (high or low syntactic interference) × 2 (high or low semantic interference) factorial repeated measures ANOVA using error terms based on participant (F1) and item (F2) variability. The results of these ANOVAs are presented together with the min-F′statistic (Clark, 1973). For comparisons between condition means, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported, calculated using the mean squared error (MSE) of the associated effects from the participant analyses according to the procedure for within-participant CIs described by Loftus and Masson (1994; Masson & Loftus, 2003). All reported means are based on analyses with participants as the random factor. Only data from trials in which participants answered “yes” to the “Got it?” question were included in the reading time analysis. These methods and conventions for presentation are followed throughout the article.

For the reading time measure, three regions of interest were identified (see Table 1). The first is the critical region, containing the verb for the long-distance dependency. The second is referred to as the spillover region, containing the two words following the critical region. The last region contains only the last word of the sentence. Although it is common practice not to analyze the last word in sentence-processing experiments because of the expectation that reading times in this position are confounded with “sentence wrap-up” effects (Just & Carpenter, 1980; King & Just, 1991), we hypothesized that at least some of these sentence wrap-up effects may be related to the interference manipulations. In particular, if participants are distracted by the interfering NP, then incorrect attachments may not be identified until final interpretive processing is done at the end of the sentence.

All regions were identical for all conditions, and consequently no length corrections (i.e., number of characters) were performed on the data. Reading times were trimmed to within 2.5 times the standard deviation for each condition, and extreme times were replaced with the cutoff value. This affected 2.5% of the data.

Results

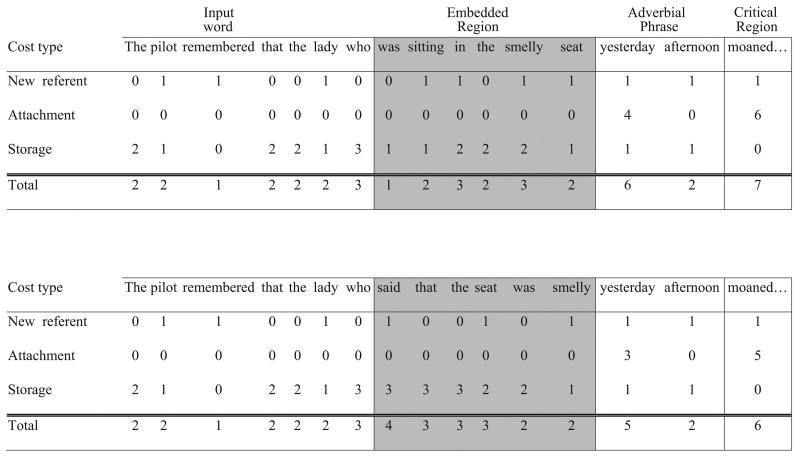

Table 3 presents both the proportion of the sentences in each condition for which participants said that they did “Get it” and reading time results. Table 4 presents the results of 2 × 2 within-subject ANOVA testing on the four interfering conditions. For brevity, the table reports results only for regions with at least one significant F statistic.

Table 3.

Mean Accuracy and Reading Times in “Got It?” Task in Experiment 1, With Participants as the Random Factor

| Reading time (ms)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interference type | Accuracy | Critical region | Spillover region | Last word |

| LoSyn/LoSem | .91 (.02) | 858 (24) | 566 (16) | 723 (43) |

| LoSyn/HiSem | .83 (.03) | 912 (34) | 571 (16) | 697 (41) |

| HiSyn/LoSem | .81 (.03) | 871 (30) | 551 (18) | 667 (37) |

| HiSyn/HiSem | .78 (.03) | 875 (30) | 568 (15) | 822 (81) |

Note. Values in parentheses are standard errors. LoSyn and HiSyn refer to low and high syntactic interference conditions, respectively; LoSem and HiSem refer to low and high semantic interference conditions, respectively.

Table 4.

Experiment 1: Analysis of Variance Results for All Dependent Measures

| Main effect

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Syntactic interference | Semantic interference | Interaction |

| “Got it” response | F1(1, 34) =14.14, p < .001, MSE1 = 0.015 | F1(1, 34) = 9.96, p <.003, MSE1 = 0.010 | F1 = 2.41, ns |

| F2(1, 47) = 8.87, p < .005, MSE2 = 0.036 | F2(1, 47) = 5.61, p < .02, MSE2 = 0.022 | F2 = 1.0, ns | |

| minF′(1, 81) = 5.45, p < .02 | minF′ (1, 80) = 3.59, p < .07 | ||

| Reading time | |||

| Critical region | F1 < 1, ns | F1(1, 34) = 6.33, p < .02, MSE1 = 4,636 | F1 = 2.36, ns |

| F2 < 1, ns | F2(1, 46) = 4.11, p < .05, MSE2 = 13,336 | F2 = 1.57, ns | |

| minF′ (1, 81) = 2.49, p < .12 | |||

| Last word | F1 < 1, ns | F1(1, 34) = 3.06, p < .09, MSE1 = 47,814 | F1 (1, 34) = 5.39, p < 03, MSE1 = 53,049 |

| F2 < 1, ns | F2 (1, 46) = 5.22, p < .03, MSE2 = 68,254 | F2 (1, 46) = 7.14, p < .02, MSE2 = 74,989 | |

| minF′ (1, 68) = 1.92, p < .17 | minF′ (1, 74) = 3.07, p < .09 | ||

For the “Got it?” measure, a main effect of syntactic interference was observed, with the HiSyn sentences being more difficult than the LoSyn sentences (.79 vs. .87; CI = .04). Similarly, a main effect of semantic interference was found, with the HiSem sentences being more difficult than the LoSem sentences (.80 vs. .86, CI = .03). The interaction was not significant. Nevertheless, because the local coherence hypothesis predicts an effect of semantic interference only in the LoSyn conditions, simple effects of semantic interference were tested. The data show that the effect of semantic interference was 8% in the LoSyn conditions and 3% in the HiSyn conditions. The effect was significant in the LoSyn conditions, F1(1, 34) = 13.65, p < .001, MSE1 = 0.016; F2(1, 47) = 5.61, p < .02, MSE2 = 0.051, but not in the HiSyn conditions (Fs < 1).

For the analysis of reading times in the critical region, the main effect of syntactic interference was not significant (F < 1). A significant main effect of semantic interference was observed, with the HiSem conditions being slower than the LoSem conditions (893 ms vs. 864 ms; CI = 23). The interaction was not significant. However, as with the “Got it?” judgments and as predicted by the local coherence account, the semantic interference effect was much larger in the LoSyn conditions (54 ms), F1(1, 34) = 6.85, p < .02, MSE1 = 14,601; F2(1, 46) = 4.24, p < .05, MSE2 = 33,049, than in the HiSyn conditions (4 ms; Fs < 1, ns).

No significant effects were observed in the spillover region (all Fs < 1). Reading times for the last word revealed no effect of syntactic interference (Fs < 1). The effect of semantic interference was marginal in the analysis by participants but significant in the analysis by items. This is due to the HiSem conditions being read more slowly than the LoSem conditions (789 ms vs. 701 ms; CI2 = 77). The interaction was significant, F1(1, 34) = 5.39, p < .03; F2(1, 46) = 7.14, p < .02. Unlike the case for “Got it?” judgments and for reading times in the critical region, this interaction reflected a greater effect of semantic interference in the HiSyn conditions (155 ms), F1(1, 34) = 4.93, p < .04, MSE1 = 170,674; F2(1, 46) = 8.34, p < .01, MSE2 = 211,618, than in the LoSyn conditions (−27 ms; Fs < 1).

Discussion

The effect of syntactic interference observed in Van Dyke and Lewis (2003) was replicated in the offline “Got it?” task data, with HiSyn conditions receiving a lower proportion of positive responses than LoSyn conditions. This finding is consistent with the view that syntactic interference creates difficulty for making the correct attachment owing to the ambiguity of the available retrieval cues. However, the reading data in the critical region did not reveal an online effect. This finding is inconsistent with previous results and may be due to the loosely defined task; if participants were actually distracted by the intervening subject NP in the HiSyn conditions, there may be no reason for them to disturb their reading, because they erroneously believe that they have “gotten” the sentence.

The effect of semantic interference was observed in the offline “Got it?” data; however, in pairwise comparisons the effect was present only in the LoSyn conditions. This is consistent with the results of Tabor, Galantucci, and Richardson (2004), who observed that locally coherent dependencies that were inconsistent with a sentence’s global interpretation create processing difficulty. They observed the effect both in reading times and in grammaticality judgments. The current data converge with theirs in that the semantic interference effect in the LoSyn constructions, in which the semantic manipulation created a local coherence with the critical verb, was also observed in slowed reading times at the critical region. The current data also extend their findings, in that the semantic interference effect was observed in the HiSyn conditions, where there was no local coherency. This effect was observed at the last word, which was later than the effect in the LoSyn conditions, suggesting that it may take longer for readers to realize they have created an incorrect interpretation when both the syntactic and the semantic properties of the distractor fit the retrieval cues from the verb.

Experiment 2: Reading Comprehension

The “Got it?” task from Experiment 1 provided preliminary evidence for both syntactic and semantic retrieval interference; however, the “Got it?” task makes the interpretation of the data somewhat problematic because there is no direct test of how well participants understood the sentences. To address this problem, the current experiment used comprehension questions as the offline measure to encourage participants to integrate incoming material into a consistent interpretation. The offline comprehension data are particularly important for evaluating the role of interference, as the essence of the effect is that an intervening NP will be incorrectly retrieved and interpreted as the subject of the cuing verb because of its match with the verb’s retrieval cues. If evidence for this incorrect interpretation in offline comprehension results were found, this would not only support the retrieval interference account but also suggest that when incorrect retrievals occur they are not easily corrected. If, however, the effect is present only in online data, then it would appear that when incorrect retrievals occur, they can be reanalyzed online, resulting in only momentarily longer reading times, without lasting effects on the sentence’s final interpretation.

A second aim of the current experiment is to seek online evidence for the syntactic interference effect. As noted above, Experiment 1 did not reveal this effect, despite the fact that the two LoSem conditions (LoSyn/LoSem and HiSyn/LoSem) were nearly identical to the conditions in Van Dyke and Lewis (2003), where the effect was first demonstrated. One explanation for this failure to replicate is that the task in Experiment 1 was quite different from that in the original study, which used self-paced reading with yes–no comprehension questions. In Experiment 2, we use an eye-tracking method that provides a highly naturalistic reading situation. If the previously observed effect was not an artifact due to a particular method, then we would expect it to be observed in the current experiment, especially in the LoSem conditions, which are free from any ambiguity associated with the semantics of the distracting NP.

Finally, the online data in Experiment 1 suggested that the semantic interference effect arises later in the HiSyn conditions (in the last region) than in the LoSyn conditions, where it occurs in the critical region. This is unexpected according to the retrieval account, because effects are expected at the point where the critical retrieval is made (i.e., the critical region). One possibility is that the later semantic effect arises because the strong (syntactic and semantic) fit of the incorrect NP to the verb causes participants to be “garden pathed” into believing they have created a coherent parse. In this case, they may detect the inconsistency only as a part of sentence-final wrap-up, where they discover that they have incorrectly interpreted a single NP in two incompatible grammatical roles. This may initiate attempts to reanalyze, resulting in slower reading times. Further data are necessary to clarify why it would be easier to initiate such reanalyses in the LoSyn conditions, hence producing an earlier effect. With Experiment 2, we seek to discover whether these timing differences were an artifact of the moving-window paradigm or whether they can be observed in the more natural reading context provided by use of an eye tracker.

The eye-tracking paradigm allows measures of both “early” processing and “later” processing, as well as a qualitative measure of reading difficulty (i.e., proportion of regressions back in order to reread portions of the sentence). Earlier processing is captured in first-pass reading times, which include all fixations within a region, starting with the first fixation until the reader’s gaze exits the region. Later processing is characterized by regression path time and total time. Regression path includes all fixations from the first fixation in the region and all fixations in the current or in prior regions until the reader’s gaze moves rightward out of the region (e.g., Brysbaert & Mitchell, 1996; Konieczny, Hemforth, Scheepers, & Strube, 1997). This is generally interpreted as the time needed to integrate a string before the reader is ready to process new material and may therefore include processing time associated with reinterpretation of incorrect dependencies. In cases where there are no leftward regressions, regression path time is equivalent to first-pass time. Total time includes both the first-pass fixation and all subsequent fixations in a region after the eyes have exited that region and returned, including rereading time originating from regions before or after the current region.

Method

Participants

Thirty-six participants from the New Haven, Connecticut, area were recruited via advertisements in local newspapers and fliers distributed around the city. They participated in this study as part of a larger study investigating individual differences in sentence processing and were paid $12.50/hr for 2.5 hr of testing (1.5 hr of reading skills testing and 1 hr of eye-tracking time). All of the participants were between the ages of 16 and 24 and had reading comprehension scores at the 12th-grade level or above on the even items from the Peabody Individual Achievement Test (Markwardt, 1998).1 All were native speakers of American English, and none were university students.

Materials

Thirty-six sets of experimental items were chosen from the piloted pool discussed above, without regard for whether they had appeared in Experiment 1. Four lists of items were constructed, and each participant received only one of the four conditions from each set. The items were presented in blocked random order so that every experimental item was separated by three filler items, which were sentences from a different experiment. A total of 144 sentences were presented during the experiment.

After every experimental sentence and after half of the filler sentences, a comprehension question followed. The question was presented in a cloze format that tested the critical dependency of the associated experimental item with a two-alternative forced-choice decision. For example, in the sentences illustrated in Table 1, the question was “__ was complaining about the investigation.” The correct answer for this example is resident, and possible distractors are worker (matrix subject) or neighbor (intervening noun). So that we could evaluate how often participants chose an incorrect noun as the subject of the critical verb, the LoSem conditions had worker as the distractor, as it was the only other semantically appropriate noun in the sentence. In the HiSem conditions, two semantically appropriate nouns occurred in the sentence (worker and neighbor), but neighbor was always presented as the distractor to allow us to evaluate whether participants would in fact interpret the intervening noun as the subject of the critical verb. These choices enabled a preliminary test of whether incorrect retrievals have specific consequences for comprehension. If participants were no more likely to choose this noun than the matrix noun, this might suggest a more general comprehension failure, one perhaps related to the complexity of the later portions of the sentence. Admittedly, this introduced a confound of the semantic manipulation and the foil for the comprehension question, an issue that was addressed in Experiment 3.

Procedure

Participants were seated in front of a 17-in. display with their eyes approximately 64 cm from the display. They wore an Eyelink II head-mounted eye tracker (SR Research, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), sampling at a rate of 250 Hz from both eyes. Sentences were presented one at a time on a single line, with a maximum of 90 characters, using a monospace font. Type size was such that each character subtended about 17 min of visual arc. The eye tracker was calibrated using a series of nine fixed targets distributed around the display, followed by a 9-point accuracy test. Calibration was monitored throughout the experiment and was repeated after any breaks or whenever the experimenter judged necessary. Data were collected from both eyes, but analyses were done only on the right eye for all participants except one, whose right eye would not calibrate. Data from this participant’s left eye were used for the analyses.

Prior to the experiment, participants were instructed to read each sentence for comprehension and told that they would be required to answer a comprehension question. Participants were also told that they could take a break at any time during the experiment. Each trial began with a screen containing a fixation point in the middle left of the display. While fixating on this point, participants were to press a button to bring up a sentence (the sentence would not appear unless participants fixated on the fixation point). After they had read the sentence, participants pressed the same button to view the comprehension question. The question appeared in the center of the screen; the two possible answers (the correct answer and the distractor) appeared three lines below, one to the left of center and one to the right of center. Participants indicated their answer by pressing the associated button on a button box; for example, if the answer appeared to the left of center they were to press the left button. The position of the correct answer was counterbalanced throughout the experiment. Participants were limited to 10 s for reading the stimulus sentence and 30 s for answering the comprehension question. If participants had not signaled that they had completed reading the sentence before the 10-s limit, the computer moved on to the comprehension question automatically. This occurred in less than 5% of trials. Participants were told to make their best guess at the comprehension question if they were unsure of the answer. If they had not answered within the 30-s limit, the computer moved on to the next item. This occurred in less than 1% of trials.

Data Analysis

All dependent measures were analyzed using a 2 (syntactic interference) × 2 (semantic interference) ANOVA. In addition to accuracy on the comprehension question, four eye-tracking measures (first pass, regression path, total reading time, and proportion of regressions back) are reported on the same three regions of interest analyzed in Experiment 1 (see Table 1). Data from accurate trials only were included in reading time analyses. As in previous experiments, analyses were done on raw reading times as the material was identical in all conditions. Fixations of less than 50 ms were not recorded, and any reading times greater than 2.5 times the standard deviation for that condition were replaced by the cutoff value. Across all reading time measures, this affected 2.4% of the data.

Results

Comprehension Questions

Results are presented in Table 5, and the results of ANOVA testing are presented in Table 6. The main effect of syntactic interference was significant both by participants and by items, with participants being more accurate on the LoSyn constructions than on the HiSyn constructions (.86 vs. .79; CI = .04). The main effect of semantic interference was also significant in both analyses, with the LoSem conditions being easier than the HiSem conditions (.88 vs. .77; CI = .05). The interaction was not significant. Nevertheless, pairwise comparisons of the effect of semantic interference in the LoSyn and HiSyn conditions were conducted separately, because the local coherence account predicts the effect in the LoSyn conditions only. This prediction was not supported in this experiment, as the effect of semantic interference was highly significant in both the LoSyn and HiSyn conditions. For LoSyn, the difference was 8%, F1(1, 35) = 9.45, p < .005, MSE1 = 0.025; F2(1, 35) = 11.34, p < .003, MSE2 = 0.021; for HiSyn, the difference was 13%, F1(1, 35) = 11.44, p < .003, MSE1 = 0.05; F2(1, 35) = 15.77, p < .001, MSE2 = 0.039.

Table 5.

Mean Accuracy Scores for Comprehension Questions in Experiment 2, With Participants as the Random Factor

| Interference type | Accuracy |

|---|---|

| LoSyn/LoSem | .90 (.02) |

| LoSyn/HiSem | .82 (.03) |

| HiSyn/LoSem | .86 (.03) |

| HiSyn/HiSem | .73 (.04) |

Note. Values in parentheses are standard errors. LoSyn and HiSyn refer to low and high syntactic interference conditions, respectively; LoSem and HiSem refer to low and high semantic interference conditions, respectively.

Table 6.

Experiment 2: Analysis of Variance Results for Comprehension Questions

| Main effect

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Syntactic interference | Semantic interference | Interaction |

| Accuracy | F1(1, 35) = 9.49, p < .005, MSE1 = .016 | F1(1, 35) = 20.35, p < .001, MSE1 = .019 | F1 <1, ns |

| F2(1, 35) = 6.27, p < .02, MSE2 = .025 | F2(1, 35) = 26.68, p < .001, MSE2 = .015 | F2 = 1.51, ns | |

| minF′(1, 67) = 3.78, p < .06 | minF′(1, 69) = 11.54, p < .002 | ||

Reading Time Measures

Table 7 summarizes the results for each measure in the regions of interest.

Table 7.

Experiment 2: Raw Reading Times (in Milliseconds) and Proportion of Regressive Eye Movements for Each Region for Each Dependent Measure, With Participants as the Random Factor

| Measure and interference type | Critical region | Spillover region | Final word |

|---|---|---|---|

| First pass | |||

| LoSyn/LoSem | 376 (16) | 320 (12) | 286 (19) |

| LoSyn/HiSem | 382 (19) | 364 (21) | 274 (19) |

| HiSyn/LoSem | 413 (21) | 325 (16) | 259 (20) |

| HiSyn/HiSem | 418 (19) | 296 (15) | 271 (22) |

| Regression path | |||

| LoSyn/LoSem | 454 (26) | 970 (98) | 1,695 (213) |

| LoSyn/HiSem | 495 (30) | 1,205 (100) | 1,806 (183) |

| HiSyn/LoSem | 594 (41) | 1,365 (140) | 1,925 (192) |

| HiSyn/HiSem | 663 (44) | 1,295 (140) | 2,131 (244) |

| Total time | |||

| LoSyn/LoSem | 630 (35) | 502 (30) | 362 (36) |

| LoSyn/HiSem | 653 (35) | 540 (29) | 373 (35) |

| HiSyn/LoSem | 738 (42) | 491 (25) | 349 (34) |

| HiSyn/HiSem | 761 (38) | 493 (24) | 360 (40) |

| Proportion of regressions | |||

| LoSyn/LoSem | .12 (.02) | .54 (.05) | .81 (.05) |

| LoSyn/HiSem | .14 (.02) | .50 (.05) | .87 (.04) |

| HiSyn/LoSem | .18 (.02) | .60 (.05) | .92 (.03) |

| HiSyn/HiSem | .22 (.03) | .53 (.04) | .86 (.05) |

Note. Values in parentheses are standard errors. LoSyn and HiSyn refer to low and high syntactic interference conditions, respectively; LoSem and HiSem refer to low and high semantic interference conditions, respectively.

Critical region

Table 8 presents the results of ANOVA testing for all dependent measures in this region. The syntactic interference effect was significant for all four measures, and no other effects were significant. For the first-pass reading times, the mean reading time was 379 ms for LoSyn versus 416 ms for HiSyn (CI = 25). Tests for simple effects showed the effect to be significant for the LoSem conditions in the analysis with participants as the random factor, but not for items, F1(1, 35) = 4.82, p < .04, MSE1 = 10,398; F2 = 2.76. The effect was marginal in the HiSem conditions in the analysis by participants, F1(1, 35) = 3.81, p < .06, MSE1 = 12,387; F2 = 2.08.

Table 8.

Experiment 2: Analysis of Variance Results for Reading Time Measures in the Critical Region

| Main effect

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Syntactic interference | Semantic interference | Interaction |

| First pass | F1(1, 35) = 8.32, p < .01, MSE1 = 5,847 | F1 < 1.13, ns | F1 < 1, ns |

| F2(1, 35) = 5.47, p < .03, MSE2 = 5,391 | F2 < 1, ns | F2 < 1, ns | |

| minF′ (1, 67) = 3.30, p < .07 | |||

| Regression path | F(1, 35) = 27.21, p < .001, MSE1 = 31,490 | F1 (1, 35) = 3.24, ns, MSE1 = 33,555 | F1 < 1, ns |

| F2(1, 35) = 20.51, p < .001, MSE2 = 33,402 | F2 (1, 35) = 3.12, ns, MSE2 = 22,632 | F2 < 1, ns | |

| minF′ (1, 69) = 11.69, p < .002 | |||

| Total time | F1(1, 35) = 29.95, p < .001, MSE1 = 14,028 | F1 < 1, ns | F1 < 1, ns |

| F2(1, 35) = 12.24, p < .001, MSE2 = 27,344 | F2 < 1, ns | F2 < 1, ns | |

| minF′ (1, 60) = 8.69, p < .005 | |||

| Regressive eye movements | F1(1, 35) = 10.71, p < .002, MSE1 = 0.017 | F1 < 2.07, ns | F1 < 1, ns |

| F2(1, 35) = 6.99, p < .01, MSE2 = 0.024 | F2 < 1.27, ns | F2 < 1, ns | |

| minF′ (1, 67) = 4.23, p < .05 | |||

For the regression path measure, the mean reading time was 475 ms for LoSyn versus 629 ms for HiSyn (CI = 59). In pairwise comparisons this effect held in both the LoSem conditions, F1(1, 35) = 15.23, p < .001, MSE1 = 46,241; F2(1, 35) = 6.49, p < .02, MSE2 = 66,300, and the HiSem conditions, F1(1, 35) = 15.38, p < .001, MSE1 = 66,614; F2(1, 35) = 15.50, p < .001, MSE2 = 64,459.

For total time in the region, the mean reading time was 642 ms for LoSyn and 750 ms for HiSyn (CI = 39). The pairwise comparisons showed the effect in both the LoSem conditions, F1(1, 35) = 10.32, p < .002, MSE1 = 40,737; F2(1, 35) = 6.43, p < .02, MSE2 = 37,489, and the HiSem conditions, F1(1, 35) = 15.34, p < .001, MSE1 = 27,376; F2(1, 35) = 8.84, p < .005, MSE2 = 50,181.

Participants made regressive eye movements backward from the critical region in 17% of trials (see Table 7). Despite this small number of regressions, the syntactic interference effect was observed (.13 for LoSyn vs. .20 for HiSyn; CI =.04). This was significant for the LoSem conditions, F1(1, 35) = 5.54, p < .03, MSE1 = 0.022, although not by items (F2 = 1.24). The syntactic effect in the HiSem conditions was also significant, F1(1, 35) = 4.98, p < .04, MSE1 = 0.053; F2(1, 35) = 6.13, p < .02, MSE2 = 0.054.

Although the pattern of reading times was consistent with the semantic interference effect in all measures, the effect did not reach significance in any measure. There was a marginal effect (p < .09) in the regression path measure (524 ms for LoSem vs. 579 ms for HiSem; CI = 60). The interaction was not significant for any measure.

Spillover region

Table 9 presents the results of ANOVA testing in this region; only measures with significant effects are displayed. In the first-pass reading measure, the effect of syntactic interference was significant; however, the pattern of results was opposite to the expected effect (342 for LoSyn vs. 310 for HiSyn; CI = 24). This finding must be interpreted in the context of the significant crossover interaction in which the semantic interference effect was significant with means in the expected direction for the LoSyn conditions (320 ms for LoSyn/LoSem vs. 364 ms for LoSyn/HiSem; CI = 37), F1(1, 35) = 5.58, p < .02, MSE1 = 12,625; F2(1, 35) = 4.29, p < .05, MSE2 = 22,762, but not for the HiSyn conditions. Although the effect in the HiSyn conditions was not significant, F1(1, 35) = 3.05, p < .10, MSE1 = 9,562; F2(1, 35) = 1.57, MSE2 = 8,571, the pattern of means was in the direction opposite that predicted (325 ms for HiSyn/LoSem vs. 296 ms for HiSyn/HiSem; CI = 32). The presence of the effect in the LoSyn conditions is consistent with both the interference account and the local coherence account; however, neither account predicts the observed pattern of reading times in the HiSyn conditions. The absence of a significant effect in the HiSyn conditions is consistent with the local coherence account.

Table 9.

Experiment 2: Analysis of Variance Results for Reading Time Measures in the Spillover Region

| Main effect

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Syntactic interference | Semantic interference | Interaction |

| First pass | F1(1, 35) = 6.58, p < .02, MSE1 = 5,471 | F1 < 1, ns | F1(1, 35) = 5.22, p < .03, MSE1 = 9,107 |

| F2(1, 35) = 4.18, p < .05, MSE2 = 9,888 | F2 < 1, ns | F2(1, 35) = 8.01, p < .01, MSE2 = 5,728 | |

| minF′ (1, 67) = 2.57, p < .12 | minF′ (1, 67) = 3.16, p < .08 | ||

| Regression path | F1(1, 35) = 12.27, p < .001, MSE1 = 172,795 | F1 < 1, ns | F1(1, 35) = 3.45, ns |

| F2(1, 35) = 8.89, p < .005, MSE2 = 434,864 | F2 < 1, ns | F2(1, 35) = 2.22, ns | |

| minF′ (1, 69) = 5.16, p < .03 | |||

In the regression path measure, the effect of syntactic interference was significant (1,087 ms for LoSyn vs. 1,330 ms for HiSyn; CI = 137). Pairwise comparisons showed that the syntactic interference effect was statistically reliable in the LoSem conditions (395 ms), F1(1, 35) = 15.60, p < .001, MSE1 = 360,080; F2(1, 35) = 14.82, p < .001, MSE2 = 472,362, but not in the HiSem conditions (Fs < 1). The semantic interference effect was not significant. There was a trend for a crossover interaction in the analysis by participants (p < .07), but this effect did not near significance in the analysis by items. As predicted by the local coherence account, the effect of semantic interference was much greater in the LoSyn conditions (234 ms), F1(1, 35) = 9.31, p < .005, MSE1 = 212,235, although it did not reach significance in the analysis by items (F2 = 2.20). The semantic interference effect in the HiSyn conditions was −70 ms, in the direction opposite that predicted, but this did not reach significance (Fs < 1). There were no significant effects for the total reading time measure. Overall, participants made regressions out of the spillover region on 57% of the trials; however, there were no significant effects of the experimental manipulations.

Final region

Table 10 presents the results of ANOVA testing in this region; as before, only measures with significant effects are displayed. There were no significant effects in the first-pass reading times at the last word. In the regression path measure there was a significant effect of syntactic interference (1,751 ms for LoSyn vs. 2,028 ms for HiSyn; CI = 222). Pairwise comparisons revealed that the effect was reliable in the HiSem conditions but only in the analysis by items, F1(1, 27) = 2.76; F2(1, 35) = 3.98, p < .05, MSE2 = 1,051,151. The effect was not reliable in the LoSem conditions (Fs < 1.64). The effect of semantic interference was significant in the analysis by items (1,738 ms for LoSem vs. 2,022 ms for HiSem; CI = 235), but this effect did not reach significance in the analysis by participants (1,810 ms for LoSem vs. 1,969 ms for HiSem; CI = 214). The interaction was not significant. Although the local coherence account predicts no effect of semantic interference in the HiSyn conditions, the effect was numerically larger in the HiSyn conditions (206 ms) and statistically reliable in the analysis by participants (though not by items), F1 < 1.10; F2(1, 35) = 4.92, p < .04, MSE2 = 831,501, and smaller in the LoSyn conditions (112 ms) and nonsignificant (F1 < 1; F2 < 1.05). There were no effects in the total time measure.

Table 10.

Experiment 2: Analysis of Variance Results for Reading Time Measures in the Final Region

| Main effect

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Syntactic interference | Semantic interference | Interaction |

| Regression path | F1(1, 27) = 4.74, p < .04, MSE1 = 453,349 | F1 (1, 27) = 1.69, ns, MSE1 = 419,003 | F1 < 1.00, ns |

| F2(1, 30) = 4.81, p < .04, MSE2 = 537,625 | F2 (1, 30) = 4.96, p < .04, MSE2 = 506,614 | F2 < 2.22, ns | |

| minF′ (1, 57) = 2.39, ns | minF′ (1, 44) = 1.26, ns | ||

| Regressive eye movements | F1(1, 27) = 2.83, ns, MSE1 = 0.023 | F1 < 1.00, ns | F1(1, 27) = 3.47, ns MSE2 = 0.027 |

| F2(1, 30) = 4.49, p < .05, MSE2 = 0.040 | F2 < 1.00, ns | F2 < 1.00, ns | |

| minF′ (1, 53) = 1.74, ns | |||

Participants regressed back from the final region in 87% of the trials. Table 7 shows that the syntactic interference manipulation produced more backward regressions, and this was significant in the analysis by items (.82 for LoSyn vs. .90 for HiSyn; CI = .07) but marginal in the analysis by participants (.84 for LoSyn vs. .89 for HiSyn; CI = .05, p = .10). The main effect of semantic interference was not significant. There was a trend for an interaction in the analysis by participants (p < .08), wherein fewer regressions were made when semantic interference was present in the HiSyn conditions (.92 for LoSem vs. .86 for HiSem; CI = .05). In the LoSyn conditions, the semantic manipulation resulted in more regressions (.81 for LoSem vs. .87 for HiSem; CI = .09), but this difference was not significant. In addition, the syntactic manipulation had a greater effect in the LoSem conditions (.81 for LoSyn vs. .92 for HiSyn; CI = .09), F1(1, 27) = 4.72, p < .04, MSE1 = 0.067; F2(1, 30) = 4.84, p < .04, MSE2 = 0.065. The effect of the syntactic manipulation in the HiSem conditions (.87 for LoSyn and .86 for HiSyn; CI = .06) was not significant (Fs < 1).

Discussion

This experiment is consistent with Experiment 1 in showing effects of both syntactic and semantic interference in the comprehension questions. Whereas the effect of semantic interference was confined to the LoSyn conditions in the previous experiment, there is evidence for the effect in both the LoSyn and the HiSyn conditions in the current experiment. This suggests that the results from Experiment 1 may have been influenced by the nature of the “Got it?” question, which did not directly query the interpretation participants had constructed. The cloze format used here asked participants to report which NP they had interpreted as the subject of the critical verb and so may have been a more authentic measure of participants’ interpretation.

The effect of syntactic interference was observed in the reading times at the critical region in the current experiment. This is unlike the results in Experiment 1 but is consistent with results of previous experiments (Van Dyke & Lewis, 2003). The effect occurred in all measures in the critical region, beginning from the earliest measure (first-pass reading time), and was particularly strong in the LoSem conditions, which most closely replicate previous work. This finding suggests that the syntactic role alone is sufficient to create interference effects, as participants are apparently distracted by an intervening subject in the HiSyn conditions, even when its semantic properties make it unsuitable as a subject of the critical verb. Moreover, the effect occurs early—as soon as the critical retrieval occurs.

There was also evidence of syntactic interference in the regression path measure in the spillover region. Because there is no reason to suggest a delay in integrating the critical verb into the sentence, the slowdown in this region is likely due either to slowdown actually associated with the critical region or to early attempts to reanalyze an incorrect dependency formed by retrieving the incorrect noun in the critical region in the HiSyn/LoSem conditions. The latter possibility is consistent with the absence of an effect in the first-pass measure, which would be expected if this were an actual “spillover” effect, and the fact that the syntactic effect was present only in the LoSem conditions, which suggests that participants may not have realized they had been distracted by the interfering NP when it was both semantically and syntactically suitable as the subject of the critical verb. This explanation is also consistent with the reversed effect of syntactic interference in the first-pass measure in the spillover region, caused by faster reading of the HiSyn/HiSem conditions in this region. If both the syntactic and the semantic cues from the critical verb match properties of the incorrect noun, participants may believe they have successfully integrated the critical verb into the sentence, causing them to read through the following region more quickly.

The observation of semantic interference in the reading times is also consistent with this view. Unlike in Experiment 1, where the effect in the LoSyn conditions occurred in the critical region, here the effect occurred in the spillover region and was observed in both the early measure (first pass) and the regression path measure. The semantic interference effect in the HiSyn conditions occurred at the last word, as in Experiment 1, and was observed in Experiment 2 in both the regression path measure and the proportion of regressions, although not in the first-pass or total reading time measures. The overall pattern suggests that participants have an easier time noticing that they have been distracted by the intervening NP in the LoSyn conditions and attempt to correct their interpretation prior to the end of the sentence. In contrast, participants appear to be reading to the end of the sentence in the HiSyn conditions before making attempts to revise an incorrect interpretation. The extremely low accuracy rates for the HiSyn/HiSem conditions suggest that participants often fail to correct their interpretation, and this notion is consistent with the decrease in the proportion of regressions at the last word for this condition. Participants appear to be fooled by the distracting subject NP in the HiSyn conditions, particularly when it is semantically suitable as the subject of the critical verb, and may not realize that a correction is necessary. The regression path results indicate that when participants do notice the error, they spend substantially more time rereading than when the intervening NP is not a semantically suitable subject.

These conclusions about the results in the final region must be qualified by the loss of statistical power in the analysis by participants, which occurred because some participants did not fixate the last word of the sentence. This reduced the overall number of observations available for analysis and resulted in several effects reaching significance only in the analysis by items. Although it is common for participants to skip small regions during eye tracking, these regions were chosen in order to compare the location of effects in the current experiment with those observed in Experiment 1. One aim of Experiment 3 is to investigate whether the emerging pattern wherein the semantic interference effect in the LoSyn conditions occurs prior to the end of the sentence and the effect in the HiSyn conditions occurs primarily at the last word will be extended when the size of both the spillover region and the final region is larger. The retrieval account makes the prediction that difficulty associated with the retrieval itself will occur in the critical region. Effects arising later are likely associated with attempts to reanalyze incorrect dependencies created when an interfering NP was incorrectly retrieved in the critical region and interpreted as the subject of the critical verb. Additional explanation would be required to account for a differential time course for the semantic interference effect in LoSyn versus HiSyn constructions, should this prove to be a general pattern.

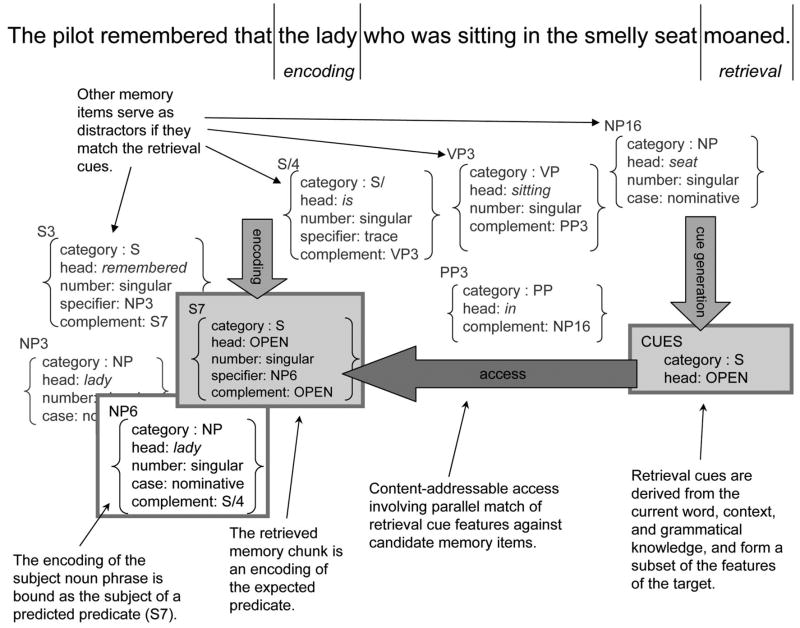

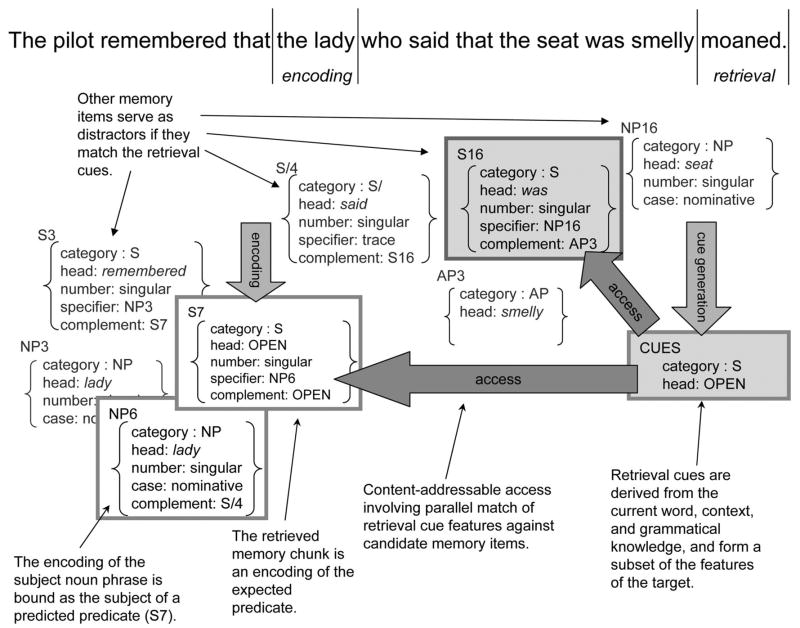

Experiment 3

One goal of the previous experiment was to replicate the online effect of syntactic interference observed in Van Dyke and Lewis (2003). Although this objective was achieved in Experiment 2, a possible alternative explanation is available for the slowdown observed in the reading times in the critical region. In all cases, the syntactic interference manipulation contained two adjacent verbs, with the verb of the embedded clause occurring just prior to the critical verb, creating the possibility that the elevated reading times at the critical verb were caused either by a “stumble” over that second verb or else by a spillover of slowed times from the first verb. The current experiment seeks to test this hypothesis with an eye-tracking experiment identical to that in Experiment 2 except that the two verbs are separated by an adverbial phrase positioned prior to the critical verb (see Table 11). If the syntactic interference effect is simply an artifact of reading two adjacent verbs, then it should not be present in the critical region in the current experiment. This also constitutes another test of whether local coherence is a necessary condition for the semantic interference effect, because the local coherence in the LoSyn conditions is now broken. If this were the cause for the difficulty caused by the semantic manipulation in the LoSyn conditions, then no difficulty should be observed here at all, even in offline comprehension measures. However, if the semantic interference effect arises whenever a suitable NP intervenes between the verbal retrieval probe and the target NP, then the effect should be observed clearly in both the LoSyn and the HiSyn conditions.

Table 11.

Example Items for Experiment 3 With Regions for Analysis

| Sentence region | Example item |

|---|---|

| Introduction | The pilot remembered that the lady |

| Intervening region | |

| LoSyn/LoSem | who was sitting in the smelly seat |

| LoSyn/HiSem | who was sitting near the smelly man |

| HiSyn/LoSem | who said that the seat was smelly |

| HiSyn/HiSem | who said that the man was smelly |

| Pre–critical region | yesterday afternoon |

| Critical region | moaned |

| Spillover region | about a refund |

| Final region | for the ticket |

Note. LoSyn and HiSyn refer to low and high syntactic interference conditions, respectively; LoSem and HiSem refer to low and high semantic interference conditions, respectively.

Method

Participants

Forty undergraduates from New York University were recruited to participate in the study. They were paid $10/hr for 1 hr of testing. All were native speakers of American English.

Materials

The items from Experiment 2 were adapted for use in this experiment by inserting an adverbial phrase prior to the critical verb in all conditions. In some cases this required vocabulary changes to the items used in Experiment 2 to make the preposition fit more naturally into the sentence. To be certain that these changes did not affect the interfering properties of the distracting NP, we conducted a plausibility norming experiment on the new materials. For each experimental sentence, nine plausibility judgments were collected (see Table 12). Judgments 1–3 were of plausibility of each NP in the sentence as the subject of the critical cuing verb. Judgments 4 and 5 queried the plausibility of the target NP versus the distracting NP as subject of the critical verb. Judgments 6–9 evaluated how naturally the inserted preposition fit with the embedded clause from the experimental sentence. Table 12 contains the norming sentences derived from the experimental sentences in Table 11, together with the mean plausibility ratings for each sentence type (1 = not plausible; 7 = highly plausible).

Table 12.

Sentences Submitted for Plausibility Judgments, Based on Experimental Materials for Experiment 3

| Test sentence | Mean plausibility rating |

|---|---|

| 1. The pilot moaned. | 6.69 |

| 2. The lady moaned. | 6.69 |

| 3. The man moaned. | 6.72 |

| 4. The smelly seat moaned. | 2.39 |

| 5. The smelly man moaned. | 6.44 |

| 6. The lady was sitting in the smelly seat yesterday afternoon. | 6.20 |

| 7. The lady was sitting near the smelly man yesterday afternoon. | 6.10 |

| 8. The lady said that the seat was smelly yesterday afternoon. | 5.73 |

| 9. The lady said that the man was smelly yesterday afternoon. | 5.75 |

Note. Rating scale ranged from 1 (not plausible) to 7 (highly plausible).

Each of the 40 participants tested in the main experiment was invited to return to participate in the norming experiment in exchange for an additional $10. Of the 40 participants, 26 responded. Participants were asked to rate each of the nine derived sentences for each experimental item, together with 72 unrelated filler items. A within-subject ANOVA was conducted on Sentences 1–3 and revealed no significant difference (Fs < 1). Pairwise comparisons of the three sentences were all nonsignificant as well (p > .27). A within-subject ANOVA on Sentences 4 and 5 yielded the expected significant difference, F1(1, 25) = 332.30, p < .001, MSE1 = 0.641; F2(1, 35) = 453.04, p < .001, MSE2 = 0.613, as this represents the semantic interference manipulation. Sentences 6–9 were analyzed with a 2 (embedding type) × 2 (NP) within-subject ANOVA. An effect of embedding was found, suggesting that the adverbial phrase fit more naturally with the embedded clause from the LoSyn sentences than with the embedded clause from the HiSyn sentences, F1(1, 25) = 29.60, p < .001, MSE1 = 0.150; F2(1, 35) = 15.17, p < .001, MSE2 = 0.404. There was no difference associated with the NPs in the two sentence types (Fs < 1). There was a hint of an interaction in the analysis by subjects, such that the type of NP affected plausibility of the embedded clauses from the LoSyn conditions more than that in the HiSyn conditions, F1(1, 25) = 3.72, p = .07, MSE1 = 0.023, but this effect did not near significance in the analysis by items (F2 < 1).

As mentioned previously, the materials from Experiment 2 were also modified so that the critical verb was followed by substantially more material (usually two prepositional phrases) so that a larger spillover and final region could be analyzed. This was done to ensure that these regions would be adequately fixated so that any effects that occurred after the critical region could be clearly measured. The regions for analysis are illustrated in Table 11.

Presentation of items in the actual experiment followed the procedure used in Experiment 2, with each participant taking part in each condition but receiving only one of the four conditions from each item set. Items were presented randomly, mixed with 108 filler items from unrelated experiments, totaling 144 sentences in the experiment.

Every experimental sentence was followed by a comprehension question presented in the same cloze format used in Experiment 2. As before, the question was followed by a set of choices three lines below it, and participants were instructed to press a button corresponding to their answer. Three choices were presented in the current experiment (compared with two in Experiment 2), reflecting each of the three NPs in the sentence that could plausibly fit with the critical verb (i.e., the same three NPs tested in Sentences 1–3 in the plausibility experiment; see Table 12).

Data Analysis

All dependent measures were analyzed using a 2 (syntactic interference) × 2 (semantic interference) ANOVA. In addition to accuracy on the comprehension question, an analysis of errors is presented. Online eye-tracking measures are reported on four regions of interest, indicated in Table 11. Analyses were conducted as described in Experiment 2 for each dependent measure in each region. Condition means from the analyses with participants as the random factor are presented together with 95% CIs, calculated as described above. Across all reading time measures, trimming affected 2.6% of the data.

Results

Comprehension Questions

Accuracy

Condition means are presented in Table 13, and the results of ANOVA testing are presented in Table 14. The main effect of syntactic interference was observed (.81 for LoSyn vs. .71 for HiSyn; CI = .04), as was the main effect of semantic interference (.81 for LoSem vs. .71 for HiSem; CI = .04). The interaction was not significant; however, as predicted by the retrieval account, the semantic interference effect was present in both the LoSyn conditions, F1(1, 39) = 7.19, p < .02, MSE1 = 0.034; F2(1, 35) = 6.50, p < .02, MSE2 = 0.036, and the HiSyn conditions, F1(1, 39) = 19.02, p < .001, MSE1 = 0.026; F2(1, 35) = 11.01, p < .003, MSE2 = 0.042.

Table 13.

Accuracy Scores for Comprehension Questions in Experiment 3, With Participants as the Random Factor

| Interference type | Accuracy |

|---|---|

| LoSyn/LoSem | .85 (.03) |

| LoSyn/HiSem | .77 (.03) |

| HiSyn/LoSem | .77 (.03) |

| HiSyn/HiSem | .66 (.03) |

Note. Values in parentheses are standard errors. LoSyn and HiSyn refer to low and high syntactic interference conditions, respectively; LoSem and HiSem refer to low and high semantic interference conditions, respectively.

Table 14.

Experiment 3: Analysis of Variance Results for Comprehension Questions

| Main effect

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Syntactic interference | Semantic interference | Interaction |

| Accuracy | F1(1, 39) = 19.23, p < .001, MSE1 = 0.019 | F1(1, 39) = 26.76, p < .001, MSE1 = 0.013 | F1 < 1.00, ns |

| F2(1, 35) = 11.76, p < .003, MSE2 = 0.029 | F2(1, 35) = 16.73, p < .001, MSE2 = 0.020 | F2 < 2.22, ns | |

| minF′ (1, 68) = 7.30, p < .01 | minF′ (1, 68) = 10.29, p < .005 | ||

Errors

Incorrect answers to the comprehension question occur when participants choose either the matrix subject of the sentence or the distracting NP (e.g., pilot or man from the example in Table 11). This occurred in 24% of trials. Table 15 presents a frequency tally for each of these choices by condition. An overall chi-square statistic on this table was significant, χ2(3) = 39.35, p < .001. Separate analyses for the subject NP, which was identical in all conditions, revealed only a marginal difference in the distribution across conditions, χ2(3) = 7.38, p < .06. The effect of condition on the probability of choosing the distracting NP was much greater, χ2(3) = 64.64, p < .001. In particular, participants were almost twice as likely to choose the distracting NP when it was a syntactic subject (HiSyn/HiSem condition) than when it was not (LoSyn/HiSem) (68 vs. 36).2

Table 15.

Frequency of Choosing the Matrix Subject or the Distracting Noun Phrase (Pilot vs. Man From Table 11)

| Interference type | Subject | Distractor |

|---|---|---|

| LoSyn/LoSem | 41 | 10 |

| LoSyn/HiSem | 44 | 36 |

| HiSyn/LoSem | 66 | 15 |

| HiSyn/HiSem | 52 | 68 |

Note. LoSyn and HiSyn refer to low and high syntactic interference conditions, respectively; LoSem and HiSem refer to low and high semantic interference conditions, respectively.

Reading Time Measures

Table 16 summarizes the results for each measure in each region of interest. All analyses were conducted on raw reading times for accurate trials only.

Table 16.

Experiment 3: Raw Reading Times (in Milliseconds) and Proportion of Regressive Eye Movements for Each Region for Each Dependent Measure, With Participants as the Random Factor

| Measure and interference type | Pre–critical region | Critical region | Spillover region | Final region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First pass | ||||

| LoSyn/LoSem | 449 (15) | 274 (9) | 448 (24) | 464 (26) |

| LoSyn/HiSem | 455 (16) | 282 (8) | 437 (19) | 480 (23) |

| HiSyn/LoSem | 462 (18) | 294 (11) | 442 (21) | 483 (29) |

| HiSyn/HiSem | 447 (17) | 280 (11) | 424 (23) | 463 (24) |

| Regression path | ||||

| LoSyn/LoSem | 472 (17) | 314 (14) | 607 (33) | 1,875 (200) |

| LoSyn/HiSem | 493 (22) | 315 (13) | 553 (28) | 2,147 (223) |

| HiSyn/LoSem | 490 (21) | 354 (18) | 625 (30) | 2,068 (232) |

| HiSyn/HiSem | 551 (36) | 344 (23) | 615 (41) | 2,474 (317) |

| Total time | ||||

| LoSyn/LoSem | 586 (29) | 414 (25) | 711 (43) | 649 (46) |

| LoSyn/HiSem | 640 (41) | 421 (25) | 707 (47) | 705 (43) |

| HiSyn/LoSem | 622 (31) | 451 (28) | 731 (51) | 675 (44) |

| HiSyn/HiSem | 710 (47) | 467 (38) | 766 (59) | 663 (46) |

| Proportion of regressions | ||||

| LoSyn/LoSem | .03 (.01) | .08 (.02) | .17 (.03) | .50 (.04) |

| LoSyn/HiSem | .04 (.01) | .08 (.02) | .11 (.02) | .54 (.04) |

| HiSyn/LoSem | .03 (.01) | .10 (.02) | .17 (.02) | .50 (.05) |

| HiSyn/HiSem | .08 (.02) | .13 (.03) | .16 (.02) | .52 (.05) |

Note. Values in parentheses are standard errors. LoSyn and HiSyn refer to low and high syntactic interference conditions, respectively; LoSem and HiSem refer to low and high semantic interference conditions, respectively.

Pre–critical region

Table 17 presents the results of ANOVA testing in this region. Only measures with significant effects are displayed. There were no significant effects in the first-pass reading times for the inserted adverbial phrase (Fs < 1). The syntactic manipulation was significant in the regression path measure (483 ms for LoSyn vs. 520 ms for HiSyn; CI = 29). Pairwise comparisons showed the effect to be nonsignificant for the LoSem conditions (Fs < 1.02). The HiSem conditions showed a significant effect in the analysis by items, F2(1, 35) = 7.98, p < .01, MSE2 = 42,110, but only a marginal effect in the analysis by participants, F1(1, 39) = 3.76, p < .06, MSE2 = 35,638. The semantic manipulation was significant in the analysis by participants (481 ms for LoSyn vs. 522 ms for HiSyn; CI = 37), but there was only a trend for an effect in the analysis by items (p = .07). The interaction was significant in the analysis by items but not in the analysis by participants. In pairwise comparisons, the semantic manipulation was not significant in the LoSyn conditions (472 ms for LoSem vs. 493 ms for HiSem; CI = 32, Fs < 1) but was marginal for the HiSyn conditions in the analysis by participants (490 ms for LoSem vs. 551 ms for HiSem; CI = 68), F1(1, 39) = 3.11, p < .09, MSE1 = 47,626, and significant in the analysis by items (492 ms for LoSem vs. 577 ms for HiSem; CI = 71), F2(1, 35) = 5.30, p < .03, MSE2 = 51,460.

Table 17.

Experiment 3: Analysis of Variance Results for Reading Time Measures in the Pre–Critical Region

| Main effect

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Syntactic interference | Semantic interference | Interaction |