Abstract

We present here the identification and characterization of Leishmania sterol 24-c-methyltransferase (SMT), as well as data on protection of mice immunized with this Ag formulated in MPL®-SE. Serological evaluation revealed that SMT is recognized by VL patients. C57BL/6 mice immunized with this vaccine candidate plus MPL®-SE showed Ag-specific Th1 immune responses characterized by robust production of IFN-γ upon specific Ag re-exposure in vitro. Upon challenge with L. infantum, mice immunized with SMT plus MPL®-SE showed significant lower parasite burdens in both spleens and livers compared with non-immunized mice or mice injected with adjuvant alone. The results indicate that SMT/MPL®-SE can be an effective vaccine candidate for use against VL.

Keywords: Visceral leishmaniasis, Sterol 24-c-methyltransferase, Vaccination

1. Introduction

Human leishmaniasis is a spectrum of diseases caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania. Leishmaniases are roughly classified into three types of diseases, cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), mucosal leishmaniasis (ML) and visceral leishmaniasis (VL) according to the clinical manifestations. Visceral leishmaniasis, generally caused by species of the L. donovani complex, i.e. L. donovani and L. infantum (chagasi), is the most severe form, with approximately 500,000 new cases reported annually (information from World Health Organization: www.who.int/leishmaniasis/en/). Active VL is characterized by hematological and hepatosplenic abnormalities, and is generally fatal unless properly treated.

The parasites are transmitted by the bite of sandflies and the infecting promastigotes differentiate into and replicate as amastigotes within macrophages in the mammalian host. In common with other intracellular pathogens, cellular immune responses are critical for protection against leishmaniasis. Th1 immune responses play an important role in mediating protection against Leishmania, including roles for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, IFN-γ, IL-12, TNF-α and NO, whereas inhibitory effects have been reported for IL-10 and TGF-β [1-9]. Effective immunization against leishmaniasis in animal models can be effected by delivery of Ag-encoding DNA vectors [10-12] or by administration of proteins formulated with Th1-inducing adjuvants including IL-12 [13-15] or TLR ligands such as CpG oligonucleotides [16-18] and monophosphoryl lipid A [19,20].

There has been significant progress in the development of safe and effective adjuvants for T cell mediated vaccines. There is also progress in characterization of defined antigens protective against VL in animal models as sub-unit or DNA vaccines such as KMP11, HASPB, A2 and CPB[21-27], whereas there are still only a limited number of bona fide vaccine candidates to combat this disease and no vaccine is available for human use yet. We have recently identified a number of L. infantum Ags by serological screening using sera from L. infantum-infected hamsters [28]. Sterol 24-c-methyltransferase (SMT), one of the identified Ags, is an enzyme involved in biosynthesis of ergosterol, which is a target molecule of leishmanicidal and fungicidal amphotericin B [29]. Amphotericin B shows selective killing activity against some protozoan parasites and fungi, as ergosterol is not found in mammalian cells. Similarly, SMT is found in several parasites, fungi and plants, but is absent in mammals.

In this study we produced recombinant SMT and tested its antigenicity, immunogenicity and protective efficacy. Because BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice show similar kinetics in parasite burden during L. infantum infection [30], we used C57BL/6 mice for evaluating protective efficacy of SMT formulated in MPL®-SE against L. infantum infection in this study, as performed in our previous study to evaluate the Leish-111f vaccine [31].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and parasites

Female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA), and were maintained in specific-pathogen-free conditions. Eight to twelve-week-old mice at the beginning of experiments were used. Promastigotes of L. infantum (MHOM/BR/82/BA-2) were cultured in MEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 0.5X MEM essential amino acids solution (Invitrogen), 0.1 mM MEM non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 25 mM HEPES, 8.3 mM glucose, 26 mM sodium bicarbonate, 1 μg/ml para amino benzoic acid, 50 μg/ml gentamicin 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 6 μg/ml hemin. Promastigotes of L. donovani and L. major (MHOM/IL/80/Friedlin) were kindly provided from Dr. David Sacks, National Institutes of Health, and cultured in Medium 199 as previously described [32]. Promastigotes in a late log or stationary phase were used for infections or Ag preparations.

2.2. Cloning of L. infantum SMT and production of the recombinant protein

An open reading frame of L. infantum SMT was amplified by PCR using L. infantum genomic DNA with a set of primers, 5' CAA TTA CAT ATG TCC GCC GGT GGC CGT G, 3' CAA TTA AAG CTT CTA AGC CTG CTT GGA CGG. The amplified PCR product was inserted in-frame with a 6xHis tag into the NdeI/HindIII site of the vector pET-28a (EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) and the insert was sequenced. The deduced amino acid sequence of L. infantum SMT was compared with those of SMTs from L. donovani (Accession No. AAR92098), L. major (CAJ09196), Trypanosoma cruzi (EAN81270) and Candida albicans (AAC26626), which were obtained from the NCBI database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), using the MegAlign software package (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI) by the Clustal method.

The pET-28a vector cloned for L. infantum SMT was transformed into E. coli Rosetta. The transformed E. coli was cultured in 2X YT medium and expression of the recombinant protein was induced by cultivation with 1M isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside for three hours. Inclusion body was formed after lysing cells by sonication and centrifuging at 10,000 g. The inclusion body was washed with 1% CHAPS and then resolubilized in 8M urea. rSMT was then purified as 6x His-tagged proteins using Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA), by binding protein to the agarose, washing the agarose with sodium deoxycolate and eluting protein with 400 μM imidazole in 8M urea. The eluted protein was dialyzed with 20 mM Tris (pH: 10) and concentration of the purified protein was measured by BCA protein assay (Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, IL). Purity of the proteins was assessed by Coomassie blue-staining following SDS-PAGE. An endotoxin level of the protein was measured by a Limulus amebocyte lysate test (Cambrex Corporation, East Rutherford, NJ) and shown to be below 10 EU/mg of protein.

2.3. Immunization of mice

Eight mice were immunized with 10 μg of rSMT plus 20 μg of MPL®-SE (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensant, Belgium) in a volume of 0.1 ml. Another group of mice was administrated with 10 μg of rSMT alone. Control groups received either saline or MPL®-SE alone. The mice were immunized subcutaneously three times at three weeks intervals in the right hind footpad and at the base of the tail.

2.4. Western blotting

Samples for immunoblotting were prepared by suspending promastigotes in SDS sample buffer followed by boiling for 5 min. Samples containing 5 × 105 promastigotes were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted on polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Polyclonal Ab obtained from mice immunized three times with 10 μg of rSMT plus 20 μg of MPL®-SE were used for western blotting. Sera from naïve mice were used at the same dilution as a control. The membranes were then probed with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG. (Rockland Immunochemicals, Inc., Gilbertsville, PA). Development was performed using Chemiluminescent Super Sensitive HRP Substrate Kit (BioFX Laboratories, Owings Mills, MD).

2.5. ELISA for human anti-SMT IgG

rSMT was diluted in ELISA coating buffer, and 96-well plates were coated with 200 ng/well of Ag followed by blocking with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 and 1% bovine serum albumin. Next, the plates were incubated with Brazilian VL patient sera (n=21) as well as sera from Chagas disease patients (n=10), endemic healthy donors (n=10) and non-endemic healthy donors (n=6) at 1:200 dilution. For total IgG, HRP-conjugated anti-human IgG (Rockland Immunochemicals) was used at the concentration of 200 ng/ml as the secondary Ab. For IgG subclass assay, HRP-conjugated anti-human IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 or IgG4 (Invitrogen) at 1/2000 dilution were used. The plates were developed with tetramethylbenzidine peroxidase substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD) and read by a microplate reader at 450 nm (570 nm reference).

2.6. ELISA for mouse anti-SMT IgG

The ELISA protocol was similar to that described above but different primary and secondary antibodies were used. Three mice per group were bled one week after the last immunization for Ab ELISA. Mouse serum samples were diluted to 1:100 and applied to the plates in fivefold serial dilutions. Then the plates were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 or IgG2a (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL). The plates were developed with the substrate and read by a microplate reader at a 450 nm wavelength.

2.7. Cytokine assay using spleen cells

Spleens were collected from three mice per group two weeks after the last immunization. 2 × 105 splenocytes in complete RPMI medium (RPMI supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml of penicillin and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin) per well were plated in a 96-well plate and then stimulated with 3 μg/ml of con A, 100 μg/ml of L. infantum soluble lysate Ag (LiSLA), 10 μg/ml of rSMT or medium alone. Culture supernatants were collected after 72 hrs cultivation and tested the levels of IFN-γ and IL-10 by sandwich ELISA.

2.8. Intracellular staining and Flowcytometry

Spleens were collected from three mice per group two weeks after the last immunization. 1 × 106 splenocytes in 100 μl of complete RPMI per well were plated in a round bottom 96-well plate and then stimulated with PMA/ionomycin, 10 μg/ml of rSMT or medium alone. Co-stimulation antibodies anti-CD28 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and anti-CD49d (eBioscience) were added to the media for a final concentration of 1 μg/ml in the well during stimulation. After 2 hours incubation at 37°C, brefeldin A (GolgiPlug: BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was added to the wells and the incubation resumed for an additional 12 hrs at 37°C. Cells were blocked with anti-CD16/32 (eBioscience) 1:50 in 50ul and then stained with AlexaFluor 700-anti-CD3 (eBioscience), PerCP-anti-CD4 (BD Biosciences), PE-anti-CD8 (BD Biosciences). Then cells were fixed using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences). Cells were again blocked with anti-CD16/32 and then intracellularly stained with FITC-anti-TNF-α (eBioscience), Pacific Blue-anti-IL-2 (eBioscience) and PE-Cy7-anti-IFN-γ (BD Biosciences). Cells were analyzed with a LSRII FACS machine (BD Biosciences) and the DIVA software.

2.9. Challenge of mice with L. infantum

Five mice per group were challenged with L. infantum three weeks after the last immunization. 5 × 106 L. infantum promastigotes were suspended in Hank's balanced salt solution and injected i.v. into the tail vein of the mouse. At four weeks after the challenge, mice were sacrificed to collect spleens and livers to determine the numbers of parasites in these tissues by limiting dilution assay. The tissues were homogenated with glass grinders and the suspensions were twofold serially diluted with complete HOMEM in 96-well microplates with NNN blood agar. Each well was examined the presence of parasites ten days after plating, and the numbers of parasites in the original tissues were calculated based on dilution factor of the last positive well.

3. Results

3.1. SMT is expressed by Leishmania species

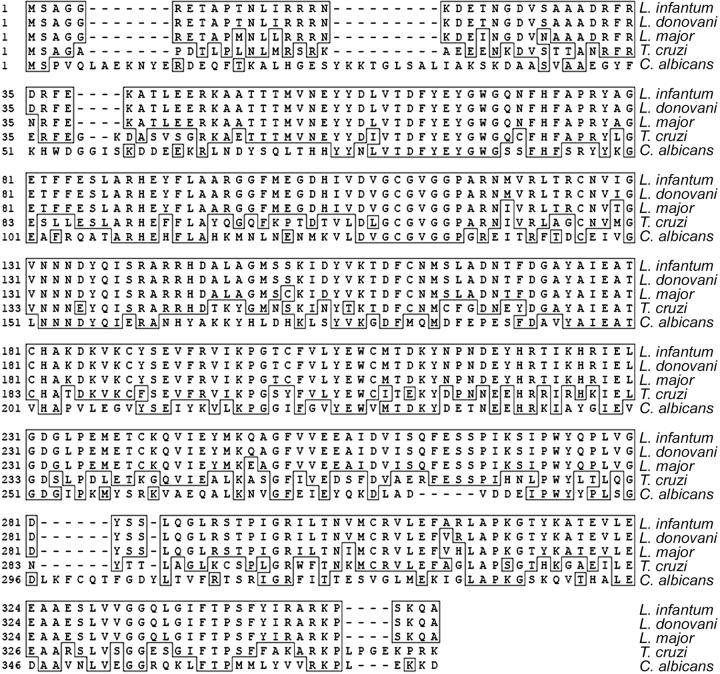

An open reading frame of SMT was cloned from L. infantum total DNA by PCR amplification using specific primers. The size was 1,062 bp and the sequence was 100% matched with the one on the database (LinJ36.4930; 1,062 bp, 353 amino acids, 39.8 kDa, obtained from GeneDB: www.genedb.org). A sequence analysis using the NCBI database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) revealed that L. infantum SMT has 99.6%, 96.6%, 66.0% and 38.5% identity to SMTs from L. donovani, L. major, T. cruzi and C. albicans, respectively (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequence alignment of SMTs from L. infantum, L. donovani, L. major, T. cruzi and C. albicans. These amino acid sequences were predicted from their corresponding cDNA sequences. Residues matching with L. infantum SMT are shown in boxes.

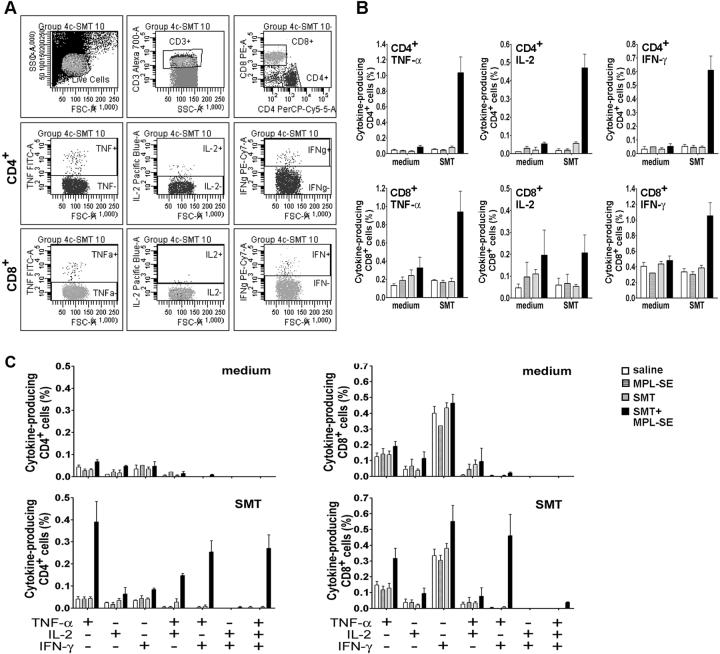

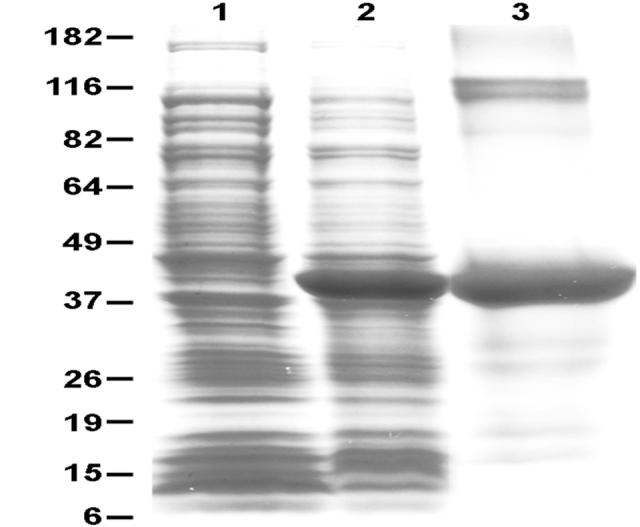

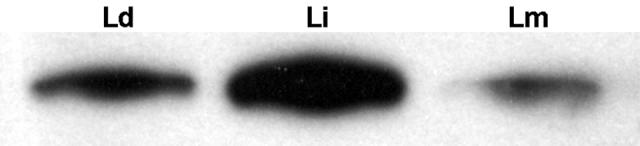

rSMT was expressed in E. coli and purified (Fig. 2). An apparent molecular mass of the protein was as predicted (42 kDa: because of 20 aa extra His-tag streach on N-terminal). Mouse polyclonal Ab raised against rSMT was used for detection of native SMT in Leishmania species by western blot analysis. Anti-SMT Ab detected a band with apparent molecular sizes of 38 kDa, which is in a same range of the predicted size, in all the Leishmania species tested, i.e. L. donovani, L infantum and L. major, whereas the intensity of the bands was different (Fig. 3). Those bands were not detected when sera from naïve mice were used as the primary Ab.

Figure 2.

Expression and purification of recombinant L. infantum SMT. Shown is a coomassie blue-stained SDS/4-20% polyacrylamide gradient gel of lysates of pET-28/SMT vector-transfected E. coli before (lane 1) or after induction with 1M IPTG (lane 2), and purified recombinant SMT (lane 3). Sizes are shown in kDa on the left.

Figure 3.

Expression of SMT by Leishmania parasites by western blotting. 5 × 105 promastigotes of L. donovani (Ld), L. infantum (Li) and L. major (Lm) were loaded on a SDS-gel and the blotted membrane was probed with mouse anti-rSMT antibody, and then with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG followed by development with the substrate.

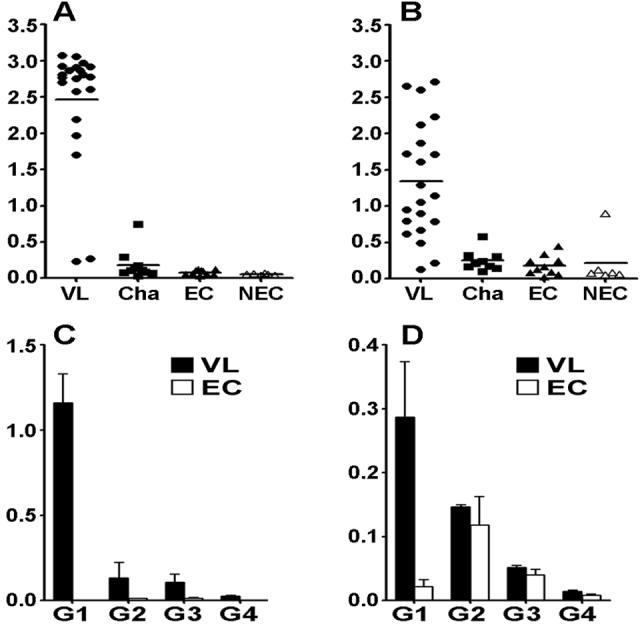

3.2. VL patient sera recognize rSMT

To determine antigenicity of Leishmania SMT in humans, examined the prevalence of antibodies to rSMT and rK39 in VL patients by ELISA using sera from 21 Brazilian VL patients. rK39 is a serodiagnostic Ag and the presence of antibodies to the Ag indicates active VL [33]. 19 of the 21 showed strong Ab responses to rK39 and those responses were specific in VL patients (Fig. 4A). Those sera showed moderate to strong reactivity to rSMT, and these Ab responses seemed to be specific in VL patients, whereas one non-endemic healthy donor showed moderate response (Fig. 4B). rSMT was recognized by Sudanese VL patients infected with L. donovani (data not shown), suggesting that SMT is antigenic in both L. donovani- and L. infantum-infected patients.

Figure 4.

Ab responses of VL patients to SMT. (A and B) Sera from VL patients (n=21), Chagas patients (Cha: n=10), endemic healthy controls (EC: n=10) and non-endemic healthy donors (n=6) were tested total IgG reactivity to rK39 (A) and rSMT (B) by ELISA and OD values of each individual are shown. Bars represent means of each group. (C and D) Shown are IgG subclass reactivity of VL patients (n=21) and endemic healthy controls (n=3) to rK39 (C) and rSMT (D). Means and SEM of each group are shown.

The sera were further examined to determine their IgG subclasses. IgG1, IgG2 and IgG3 responses to rK39 were detected in VL patient sera and IgG1 was the predominant subclass (Fig. 4C). IgG1 response was predominant to rSMT as well, despite the titers were lower than those to rK39 (Fig. 4D). Some IgG2 responses were observed in VL patient sera to rSMT, but that was not VL-specific, as health donors showed IgG2 response to this Ag. Little IgG4 responses were detected to either rK39 or rSMT.

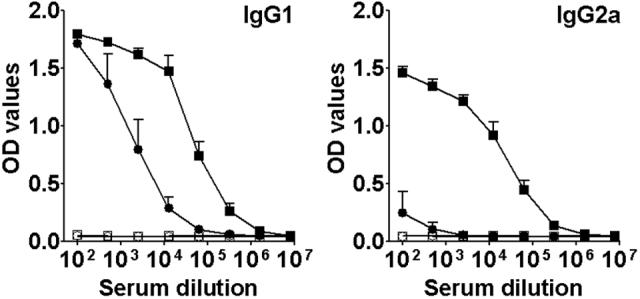

3.3. rSMT plus MPL®-SE induce immune responses with Th1 characteristics

Since the rSMT plus MPL®-SE vaccine induced protection against VL in mice, we then evaluated immune responses induced by the vaccine. Mice immunized with rSMT plus MPL®-SE showed robust humoral responses to rSMT characterized by high levels of Ag-specific IgG1 and IgG2a (Fig. 5). In contrast, immunization with rSMT alone resulted in IgG1-dominant Ab responses. Mice injected with saline or adjuvant alone showed no Ab responses to rSMT.

Figure 5.

Antibody responses of immunized mice to SMT. Levels of anti-SMT IgG1 and IgG2a of mice inoculated with saline (○), MPL®-SE alone (□), rSMT alone (●) or rSMT plus MPL®-SE (■) were evaluated by ELISA. Three mice were used per group and means and SEM of OD values of each group are shown.

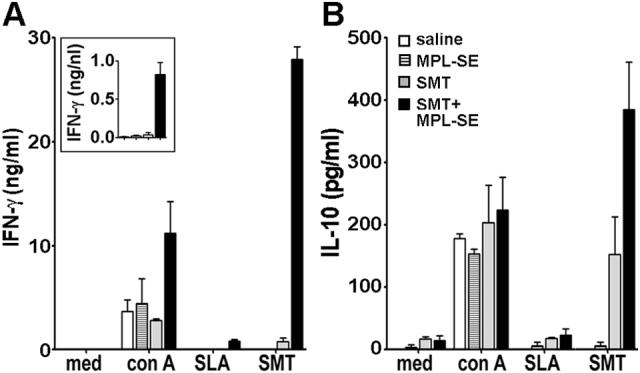

To investigate cell-mediated responses brought about by the immunization, cytokine production by spleen cells in stimulation with rSMT or LiSLA were measured. Spleen cells from mice immunized with rSMT plus MPL®-SE produced a high level of IFN-γ in response to rSMT (Fig. 6A). These mice also responded to LiSLA stimulation; albeit the magnitude of IFN-γ production was much lower than that observed with rSMT stimulation. In contrast, spleen cells from mice immunized with rSMT alone produced only a low level of IFN-γ in response to rSMT. Compared with SMT alone, SMT plus MPL-SE induced 30 times higher IFN-γ response, whereas IL-10 level was only twice higher, suggesting that MPL-SE skews immune responses to vaccine antigens toward Th1 (Fig. 6B). No detectable cytokine production was found in saline or adjuvant alone groups in stimulation with rSMT or LiSLA.

Figure 6.

Cytokine production by immunized mice in stimulation with leishmanial Ags. Spleen cells from mice inoculated with saline alone, MPL-SE alone, SMT alone or SMT plus MPL-SE were stimulated in vitro with medium alone, con A, rSMT or SLA. Culture supernatants were collected after 72 hrs stimulation and the levels of IFN-γ (A) and IL-10 (B) in the supernatants were measured by sandwich ELISA. An inset shows IFN-γ responses in stimulation with SLA using a different scale. Mean and SEM of three mice in each group are shown.

3.4. rSMT plus MPL®-SE induce both CD4+ and CD8+ cells expressing multiple Th1-type cytokines

To further investigate cellular responses induced by rSMT plus MPL®-SE vaccination, flowcytometric analysis of Th1-type cytokine production by CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells was performed. Spleen cells, which were harvested after in vitro cultivation with or without SMT, were gated based on forward and side scatter first, then CD3 expression (Fig. 7A). CD4+ or CD8+ cells were further gated from the CD3+ population. Those populations were analyzed the frequency of cells producing TNF-α, IL-2 or IFN-γ.

Figure 7.

Flowcytometric analysis of SMT-specific T-cells. (A) A representative of flowcytometry data. (B) TNF-α, IL-2 and IFN-γ production by CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells in response to SMT. Spleen cells from mice administrated with saline, MPL-SE alone, rSMT alone and rSMT plus MPL-SE were incubated with medium alone or in a presence of rSMT, and cytokine production was analyzed by flowcytometry. (C) Single-cell analysis of CD4+ (left) and CD8+ (right) T-cells producing multiple Th1-type cytokines.

FACS data show that Ag-specific CD4+ and CD8+ cells were induced by rSMT plus MPL®-SE vaccination (Fig. 7B). CD4+ cells producing TNF-α, IL-2 or IFN-γ in stimulation with rSMT were found only in that group of mice. Ag-specific CD8+ cells were also found in mice administrated rSMT plus MPL®-SE, and those cells were found producing TNF-α and IFN-γ.

When CD4+ and CD8+ cells were further divided into seven distinct populations based on expression patterns of TNF-α, IL-2 or IFN-γ at a single-cell level, it was revealed that many of Ag-specific T-cells producing multiple cytokines were induced by rSMT plus MPL®-SE (Fig. 7C). There were both CD4+ and CD8+ cells producing only TNF-α in stimulation with rSMT, whereas cells expressing only IFN-γ were little. Most of Ag-specific CD4+ T-cells producing IFN-γ were co-expressing TNF-α or both TNF-α and IL-2. Also, many of the Ag-specific CD8+ T-cells were producing both TNF-α and IFN-γ.

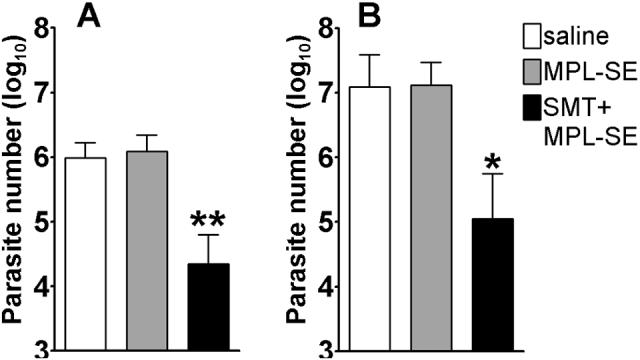

3.5. rSMT-vaccinated mice are resistant against L. infantum infection

To evaluate the protective efficacy of rSMT plus MPL®-SE vaccination against VL, immunized mice were challenged by intravenous injection of 5 × 106 L. infantum promastigotes. During L. infantum infection, C57BL/6 mice showed peak parasite burden at four weeks of infection in the liver and between four and eight weeks in the spleen (data not shown). Thus, we chose four weeks as a time point for determining parasite numbers in spleens and livers of challenged mice. Significant reduction of parasites was seen in mice immunized with rSMT plus MPL®-SE compared with those in saline or adjuvant alone groups (Fig. 8). The immunized mice showed 43-fold and 55-fold reduction in the number of parasites in spleens, 111-fold and 117-fold reduction in livers compared with saline and adjuvant alone groups, respectively. There was no significant difference observed between saline and adjuvant alone groups. This protection in SMT-immunized mice was repeatedly observed with similar magnitude.

Figure 8.

Protection against L. infantum infection by SMT immunization. Mice inoculated with saline, MPL®-SE or rSMT + MPL®-SE were challenged with L. infantum and the numbers of parasites in the spleen (A) and liver (B) were measured four weeks after the infection. Mean and SEM of five mice in each group are shown. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 by unpaired t-test compared with both saline and MPL®-SE groups. This is a representative of three independent experiments with similar results.

4. Discussion

There have been a limited number of vaccine candidates which have been shown to induce protection against VL in animal models [21-23,27]. In this study, we demonstrated that immunization with L. infantum SMT plus MPL®-SE induced a mixture of Th1 and Th2 responses to the vaccine antigen and significantly protected mice from L. infantum, a causative agent of VL in humans and dogs.

Protection derived from the L. infantum SMT plus MPL®-SE vaccine seems to be associated with Ag-specific Th1 immune responses. And this effective protection was most likely affected by the combination of Ag and adjuvant. In previous studies, we have shown that MPL®-SE contributes as a Th1-inducing adjuvant to protection against CL when formulated with a recombinant fusion protein, Leish-111f [19,20]. In this study, we showed the induction of both Ag-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells by the rSMT plus MPL®-SE vaccine. Also, we demonstrated that the rSMT plus MPL®-SE vaccine induced Ag-specific T-cells which are capable of producing multiple Th1-type cytokines in response to Ag recall. All of TNF-α, IL-2 and IFN-γ are involved in protection against VL [4,5,34]. As TNF-α synergizes with IFN-γ in killing Leishmania parasites [35], induction of Ag-specific T-cells capable of producing multiple cytokines upon Ag recall might be more beneficial for control of Leishmania infection than those producing single cytokine, and such induction may be a good indicator whether a vaccine composed of Ag and adjuvant is protective against leishmaniasis.

Because Th1 immune responses play an important role in controlling leishmaniasis, T-cell Ags have been thought to be good vaccine targets. We have attempted to identify such Ags through T-cell screening or MHC class II screening [36,37], however, none of them were protective against VL. In contrast, SMT was identified by serological screening of an expression library using VL patient sera [28]. Interestingly, most of the known vaccine Ags including HASPB1 (K26), A2 and KMP-11 are also known as serological Ags which detect antibodies in sera of VL patients [38,39]. Although the significance of Ag-specific IgG subclasses in humans is not fully understood yet, there are associations between IgG subclasses and cytokine profiles. For example, IL-4 facilitates in switching of IgM-expressing B cells to the production of IgG4 [40]. IL-10 appears to represent a switch factor for IgG1 and IgG3 [41], whereas IFN-γ induces IgG2 production while suppressing the production of IgG1 [42]. Patients with active VL have a high prevalence of antibodies to leishmanial Ags while producing the regulatory cytokine IL-10 and lacking Th1 immune responses [43-45]. Therefore, IgG1-dominant response of VL patients to SMT is indicative of the involvement of the Ag in disease promotion during human VL. We are now examining cellular immune responses of asymptomatic or cured VL patients to SMT to examine whether or not this Ag is associated with protective immunity against VL.

We have demonstrated that SMT is expressed by both L. infantum and L. donovani, the two causative agents of VL, as well as L. major causing CL in the Old World. This SMT expression pattern suggests that the Ag may also be useful in other forms of leishmaniasis. Furthermore, the lack of homology with mammalian proteins may give SMT safety advantages. SMT is also found in other pathogens including parasites and fungi such as Trypanosoma spp. [46], Candida albicans [47] and Pneumocystis carinii [48]. Although the functional role of SMT in ergosterol biosynthesis is well studied, its antigenicity during such infections has not been unknown. Thus, it is of interest to evaluate whether SMT is involved in or can be a vaccine Ag against infections other than VL.

Acknowledgements

We thank gratefully Dr. Malcolm Duthie for critical comments and Jeffrey Guderian, Raodoh Mohamath and Farah Mompoint for technical assistances.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Engwerda CR, Murphy ML, Cotterell SE, Smelt SC, Kaye PM. Neutralization of IL-12 demonstrates the existence of discrete organ-specific phases in the control of Leishmania donovani. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28(2):669–80. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199802)28:02<669::AID-IMMU669>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy ML, Wille U, Villegas EN, Hunter CA, Farrell JP. IL-10 mediates susceptibility to Leishmania donovani infection. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31(10):2848–56. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2001010)31:10<2848::aid-immu2848>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray HW, Nathan CF. Macrophage microbicidal mechanisms in vivo: reactive nitrogen versus oxygen intermediates in the killing of intracellular visceral Leishmania donovani. J Exp Med. 1999;189(4):741–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray HW, Jungbluth A, Ritter E, Montelibano C, Marino MW. Visceral leishmaniasis in mice devoid of tumor necrosis factor and response to treatment. Infect Immun. 2000;68(11):6289–93. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6289-6293.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Squires KE, Schreiber RD, McElrath MJ, Rubin BY, Anderson SL, Murray HW. Experimental visceral leishmaniasis: role of endogenous IFN-gamma in host defense and tissue granulomatous response. J Immunol. 1989;143(12):4244–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor AP, Murray HW. Intracellular antimicrobial activity in the absence of interferon-gamma: effect of interleukin-12 in experimental visceral leishmaniasis in interferon-gamma gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1997;185(7):1231–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaye PM, Bancroft GJ. Leishmania donovani infection in scid mice: lack of tissue response and in vivo macrophage activation correlates with failure to trigger natural killer cell-derived gamma interferon production in vitro. Infect Immun. 1992;60(10):4335–42. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4335-4342.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stern JJ, Oca MJ, Rubin BY, Anderson SL, Murray HW. Role of L3T4+ and LyT-2+ cells in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1988;140(11):3971–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson ME, Young BM, Davidson BL, Mente KA, McGowan SE. The importance of TGF-beta in murine visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1998;161(11):6148–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gurunathan S, Sacks DL, Brown DR, Reiner SL, Charest H, Glaichenhaus N, et al. Vaccination with DNA encoding the immunodominant LACK parasite antigen confers protective immunity to mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 1997;186(7):1137–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piedrafita D, Xu D, Hunter D, Harrison RA, Liew FY. Protective immune responses induced by vaccination with an expression genomic library of Leishmania major. J Immunol. 1999;163(3):1467–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendez S, Gurunathan S, Kamhawi S, Belkaid Y, Moga MA, Skeiky YA, et al. The potency and durability of DNA- and protein-based vaccines against Leishmania major evaluated using low-dose, intradermal challenge. J Immunol. 2001;166(8):5122–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.5122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Afonso LC, Scharton TM, Vieira LQ, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Scott P. The adjuvant effect of interleukin-12 in a vaccine against Leishmania major. Science. 1994;263(5144):235–7. doi: 10.1126/science.7904381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stobie L, Gurunathan S, Prussin C, Sacks DL, Glaichenhaus N, Wu CY, et al. The role of antigen and IL-12 in sustaining Th1 memory cells in vivo: IL-12 is required to maintain memory/effector Th1 cells sufficient to mediate protection to an infectious parasite challenge. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(15):8427–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160197797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenney RT, Sacks DL, Sypek JP, Vilela L, Gam AA, Evans-Davis K. Protective immunity using recombinant human IL-12 and alum as adjuvants in a primate model of cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1999;163(8):4481–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhee EG, Mendez S, Shah JA, Wu CY, Kirman JR, Turon TN, et al. Vaccination with heat-killed leishmania antigen or recombinant leishmanial protein and CpG oligodeoxynucleotides induces long-term memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses and protection against Leishmania major infection. J Exp Med. 2002;195(12):1565–73. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stacey KJ, Blackwell JM. Immunostimulatory DNA as an adjuvant in vaccination against Leishmania major. Infect Immun. 1999;67(8):3719–26. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.3719-3726.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker PS, Scharton-Kersten T, Krieg AM, Love-Homan L, Rowton ED, Udey MC, et al. Immunostimulatory oligodeoxynucleotides promote protective immunity and provide systemic therapy for leishmaniasis via IL-12- and IFN-gamma-dependent mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(12):6970–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coler RN, Skeiky YA, Bernards K, Greeson K, Carter D, Cornellison CD, et al. Immunization with a polyprotein vaccine consisting of the T-Cell antigens thiol-specific antioxidant, Leishmania major stress-inducible protein 1, and Leishmania elongation initiation factor protects against leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 2002;70(8):4215–25. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4215-4225.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skeiky YA, Coler RN, Brannon M, Stromberg E, Greeson K, Crane RT, et al. Protective efficacy of a tandemly linked, multi-subunit recombinant leishmanial vaccine (Leish-111f) formulated in MPL adjuvant. Vaccine. 2002;20(2728):3292–303. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basu R, Bhaumik S, Basu JM, Naskar K, De T, Roy S. Kinetoplastid membrane protein-11 DNA vaccination induces complete protection against both pentavalent antimonial-sensitive and -resistant strains of Leishmania donovani that correlates with inducible nitric oxide synthase activity and IL-4 generation: evidence for mixed Th1- and Th2-like responses in visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 2005;174(11):7160–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stager S, Smith DF, Kaye PM. Immunization with a recombinant stage-regulated surface protein from Leishmania donovani induces protection against visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 2000;165(12):7064–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosh A, Zhang WW, Matlashewski G. Immunization with A2 protein results in a mixed Th1/Th2 and a humoral response which protects mice against Leishmania donovani infections. Vaccine. 2001;20(12):59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00322-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson ME, Young BM, Andersen KP, Weinstock JV, Metwali A, Ali KM, et al. A recombinant Leishmania chagasi antigen that stimulates cellular immune responses in infected mice. Infect Immun. 1995;63(5):2062–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.2062-2069.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tewary P, Jain M, Sahani MH, Saxena S, Madhubala R. A heterologous prime-boost vaccination regimen using ORFF DNA and recombinant ORFF protein confers protective immunity against experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(12):2130–7. doi: 10.1086/430348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aguilar-Be I, da Silva Zardo R, Paraguai de Souza E, Borja-Cabrera GP, Rosado-Vallado M, Mut-Martin M, et al. Cross-protective efficacy of a prophylactic Leishmania donovani DNA vaccine against visceral and cutaneous murine leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 2005;73(2):812–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.812-819.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rafati S, Zahedifard F, Nazgouee F. Prime-boost vaccination using cysteine proteinases type I and II of Leishmania infantum confers protective immunity in murine visceral leishmaniasis. Vaccine. 2006;24(12):2169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goto Y, Coler RN, Guderian J, Mohamath R, Reed SG. Cloning, Characterization, and Serodiagnostic Evaluation of Leishmania infantum Tandem Repeat Proteins. Infect Immun. 2006;74(7):3939–45. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00101-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pourshafie M, Morand S, Virion A, Rakotomanga M, Dupuy C, Loiseau PM. Cloning of S-adenosyl-L-methionine:C-24-Delta-sterol-methyltransferase (ERG6) from Leishmania donovani and characterization of mRNAs in wild-type and amphotericin B-Resistant promastigotes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(7):2409–14. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2409-2414.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honore S, Garin YJ, Sulahian A, Gangneux JP, Derouin F. Influence of the host and parasite strain in a mouse model of visceral Leishmania infantum infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1998;21(3):231–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coler RN, Goto Y, Bogatzki L, Raman V, Reed SG. Leish-111f, a Recombinant Polyprotein Vaccine that Protects against Visceral Leishmaniasis by the elicitation of CD4+ T cells. Infect Immun. 2007 doi: 10.1128/IAI.00394-07. doi:10.1128/IAI.00394-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belkaid Y, Von Stebut E, Mendez S, Lira R, Caler E, Bertholet S, et al. CD8+ T cells are required for primary immunity in C57BL/6 mice following low-dose, intradermal challenge with Leishmania major. J Immunol. 2002;168(8):3992–4000. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burns JM, Jr., Shreffler WG, Benson DR, Ghalib HW, Badaro R, Reed SG. Molecular characterization of a kinesin-related antigen of Leishmania chagasi that detects specific antibody in African and American visceral leishmaniasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(2):775–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray HW, Miralles GD, Stoeckle MY, McDermott DF. Role and effect of IL-2 in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1993;151(2):929–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liew FY, Li Y, Millott S. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha synergizes with IFN-gamma in mediating killing of Leishmania major through the induction of nitric oxide. J Immunol. 1990;145(12):4306–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campos-Neto A, Soong L, Cordova JL, Sant'Angelo D, Skeiky YA, Ruddle NH, et al. Cloning and expression of a Leishmania donovani gene instructed by a peptide isolated from major histocompatibility complex class II molecules of infected macrophages. J Exp Med. 1995;182(5):1423–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Probst P, Stromberg E, Ghalib HW, Mozel M, Badaro R, Reed SG, et al. Identification and characterization of T cell-stimulating antigens from Leishmania by CD4 T cell expression cloning. J Immunol. 2001;166(1):498–505. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghedin E, Zhang WW, Charest H, Sundar S, Kenney RT, Matlashewski G. Antibody response against a Leishmania donovani amastigote-stage-specific protein in patients with visceral leishmaniasis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4(5):530–5. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.5.530-535.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhatia A, Daifalla NS, Jen S, Badaro R, Reed SG, Skeiky YA. Cloning, characterization and serological evaluation of K9 and K26: two related hydrophilic antigens of Leishmania chagasi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;102(2):249–61. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gascan H, Gauchat JF, Roncarolo MG, Yssel H, Spits H, de Vries JE. Human B cell clones can be induced to proliferate and to switch to IgE and IgG4 synthesis by interleukin 4 and a signal provided by activated CD4+ T cell clones. J Exp Med. 1991;173(3):747–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Briere F, Servet-Delprat C, Bridon JM, Saint-Remy JM, Banchereau J. Human interleukin 10 induces naive surface immunoglobulin D+ (sIgD+) B cells to secrete IgG1 and IgG3. J Exp Med. 1994;179(2):757–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawano Y, Noma T, Yata J. Regulation of human IgG subclass production by cytokines. IFN-gamma and IL-6 act antagonistically in the induction of human IgG1 but additively in the induction of IgG2. J Immunol. 1994;153(11):4948–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carvalho EM, Badaro R, Reed SG, Jones TC, Johnson WD., Jr Absence of gamma interferon and interleukin 2 production during active visceral leishmaniasis. J Clin Invest. 1985;76(6):2066–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI112209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghalib HW, Piuvezam MR, Skeiky YA, Siddig M, Hashim FA, el-Hassan AM, et al. Interleukin 10 production correlates with pathology in human Leishmania donovani infections. J Clin Invest. 1993;92(1):324–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI116570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miles SA, Conrad SM, Alves RG, Jeronimo SM, Mosser DM. A role for IgG immune complexes during infection with the intracellular pathogen Leishmania. J Exp Med. 2005;201(5):747–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou W, Lepesheva GI, Waterman MR, Nes WD. Mechanistic analysis of a multiple product sterol methyltransferase implicated in ergosterol biosynthesis in Trypanosoma brucei. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(10):6290–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511749200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jensen-Pergakes KL, Kennedy MA, Lees ND, Barbuch R, Koegel C, Bard M. Sequencing, disruption, and characterization of the Candida albicans sterol methyltransferase (ERG6) gene: drug susceptibility studies in erg6 mutants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42(5):1160–7. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.5.1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaneshiro ES, Rosenfeld JA, Basselin M, Bradshaw S, Stringer JR, Smulian AG, et al. Pneumocystis carinii erg6 gene: sequencing and expression of recombinant SAM:sterol methyltransferase in heterologous systems. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2001;(Suppl):144S–46S. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2001.tb00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]