We describe a patient with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) dependent relapsing chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP), unresponsive to steroids or conventional immunosuppressive agents, who achieved remission following treatment with alemtuzumab.

A 19 year old women presented with a two week history of distal lower limb paraesthesiae and distal upper limb weakness. Her symptoms worsened over four weeks but she remained mobile. There was no history of preceding infections, pain, or autonomic dysfunction. Examination revealed reduced limb muscle tone and distal weakness, more marked in the upper limbs. She was areflexic with flexor plantar responses and had reduced pin prick sensation in the hands and toes.

A lumbar puncture showed a raised protein of 1.8 g/l, with normal glucose and cell counts and negative oligoclonal bands. A preliminary diagnosis of Guillain‐Barré syndrome was made and she was treated conservatively, with good recovery.

Three months later she developed further weakness, predominantly affecting her legs. Examination revealed normal muscle tone, distal but asymmetrical limb weakness, absent reflexes, and distal sensory loss. She remained mobile with the aid of unilateral support.

Further investigations were normal or unremarkable; these included full blood count, blood film, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests, glucose, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, creatinine kinase, vitamin B‐12, folate, serum electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody, antiganglioside antibodies including anti‐GM1, anti‐double‐stranded DNA antibodies, HIV, hepatitis A, B, and C, and urinary porphyrins. Genetic testing for hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies, CMT‐1a and PMP‐22 was unremarkable. Nerve conduction studies showed absent sensory responses in the arms and an absent sural response, but normal right superficial peroneal nerve response. Motor conduction velocities were reduced to 13–25 (mean 19) m/s with evidence of conduction block.

One week after a five day course of IVIg (Octagam 22 g/day) she had improved significantly, with only mild residual distal weakness in the upper limbs. She was well for one month before suffering a further relapse, with a similar clinical pattern, and received a further course IVIg with good response. The diagnosis was revised to CIDP. No nerve biopsy was undertaken as the presentation was considered typical and confounding diagnoses had been excluded.

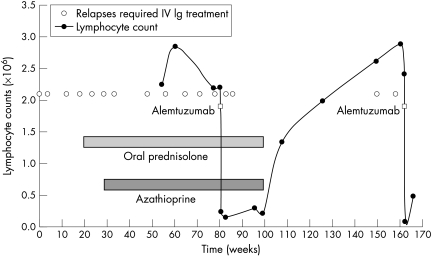

After several further relapses she was started on oral prednisolone, without benefit. Later introduction of azathioprine provided an initial partial response only. Eighteen months after disease onset the patient had experienced 11 relapses during which she was unable to walk unaided, with an average interval of seven weeks between IVIg treatments, and she had also developed wasting of the small hand muscles. After detailed discussion of treatment options and when written consent had been obtained she was treated with a five day infusion of alemtuzumab (30 mg/day), from which she experienced no significant side effects. Two further relapses occurred, at five weeks and eight and a half weeks post‐treatment, both successfully managed with IVIg. Her tendon reflexes returned and sensory deficit resolved, but some mild distal upper limb weakness remained. Oral prednisolone and azathioprine were withdrawn at 4.0 and 6.5 months respectively. The patient remained well for 16 months, but then suffered a further relapse, which was treated with IVIg with good response. A subsequent relapse occurred after 10.5 weeks, again treated with IVIg. A second course of alemtuzumab has recently been given (fig 1). Longitudinal neurophysiological studies did not correlate with clinical recovery.

Figure 1 Graph showing the relation of relapses requiring hospital admission and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) to treatment with prednisolone, azathioprine, and alemtuzumab and the lymphocyte count.

Pretreatment lymphocyte subsets showed that 73.5% of lymphocytes were CD3+, 18.4% CD4+. It was not possible to assess lymphocyte subsets post‐treatment as the total lymphocyte count was only 0.16 (×109/litre) but return to normal levels corresponded with a return of clinical activity.

The exact pathogenesis of CIDP is unknown. Pathological studies have shown T cell infiltrates on biopsies of peripheral nerves and in necropsy studies, and increased levels of interleukin 2 receptors and circulating activated peripheral T lymphocytes.1

Traditionally steroids have been the mainstay of treatment for CIDP, and their usefulness was recently confirmed in a Cochrane review. IVIg has been shown to be an effective but short lived treatment, with two thirds of patients responding; however, 60–70% require repeated courses. IVIg is expensive and associated with potentially serious side effects. Plasma exchange is considered as effective as IVIg. Various other drugs have been used in small numbers of patients, including azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, ciclosporine A, mycophenolate mofetil, and interferons. A Cochrane review recently evaluated these and concluded there was inadequate evidence to determine benefit.2 One other case report describes the use of monoclonal antibodies in CIDP, documenting a clear response to rituximab.3

Alemtuzumab (Campath 1‐H) is a monoclonal antibody used for the treatment of B cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and multiple sclerosis. It targets CD52 antigen and is thought to have a role in immune modulation. CD52 is a low molecular weight glycoprotein present on most lymphocyte lineages, monocytes, and some cells in the male reproductive system. Monoclonal antibodies directed against CD52 cause complement mediated lysis and reduce the numbers of circulating lymphocytes,4 which may explain the therapeutic effect seen in our patient.

Alemtuzumab has been associated with various side effects, including autoimmune thyroid disease, reported in a third of treated patients with multiple sclerosis. In a study of patients receiving alemtuzumab along with fludarabine and melphalan, followed by stem cell transplantation for treatment of haematological malignancies, five of 85 patients developed a progressive peripheral sensorimotor radiculoneuropathy. However, there have been no reports of similar complications in patients treated with alemtuzumab as part of conventional allograft5 or in patients with multiple sclerosis. The main reported side effects are infusion related, such as hypotension, fever, shortness of breath, and rash.

It is unclear why our patient had two relapses in the eight weeks following treatment with alemtuzumab. Effects on circulating T lymphocytes and monocytes following infusion are rapid, with a single dose of alemtuzumab causing depletion of CD8+ T cells for 30 months and CD4+ T cells for 60 months on average. However, it is likely that the mechanism of alemtuzumab's efficacy is probably not T cell depletion but rearrangement of the lymphocyte repertoire. It may be that extravascular activated lymphocytes are already primed for the pathological process and it is not until further recruitment of cells from the intravascular space is demanded that the disease process is slowed. The length of remission approximates to the time course of this drug's effectiveness in multiple sclerosis,6 in which relapses are also observed in an eight week window following treatment before disease remission.

This case report shows the potential usefulness of monoclonal antibodies as a novel treatment for severe relapsing CIDP. Further studies are needed to evaluate this as a future treatment option.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Van den Berg L H, Mollee I, Wokke J H.et al Increased frequencies of HPRT mutant T lymphocytes in patients with Guillain‐Barre syndrome and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: further evidence for a role of T cells in the etiopathogenesis of peripheral demyelinating diseases. J Neuroimmunol 19955837–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes R A, Swan A V, van Doorn P A. Cytotoxic drugs and interferons for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003(1)CD003280. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Briani C, Zara G, Zambello R.et al Rituximab‐responsive CIDP. Eur J Neurol 200411788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riechmann L, Clark M, Waldmann H.et al Reshaping human antibodies for therapy. Nature 1988332323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avivi I, Chakrabarti S, Kottaridis P.et al Neurological complications following alemtuzumab‐based reduced‐intensity allogeneic transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 200434137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coles A J, Wing M G, Molyneux P.et al Monoclonal antibody treatment exposes three mechanisms underlying the clinical course of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 199946296–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]