The Foix–Chavany–Marie opercular syndrome (FCMS), a severe form of pseudobulbar palsy due to bilateral anterior opercular lesions, may be congenital or acquired, persistent or intermittent.1 FCMS due to epilepsy has been described nearly exclusively in childhood.1 We report the case of an adult patient in whom non‐convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) manifested with opercular syndrome, and which was completely reversible with treatment for epilepsy.

Case report

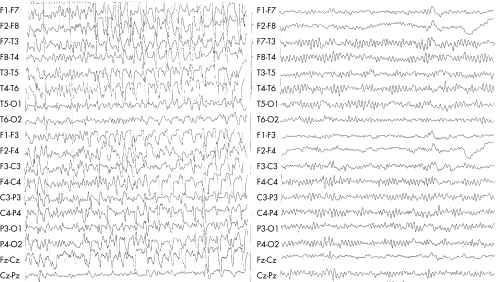

A 55‐year‐old patient with chronic renal failure on haemodialysis was admitted to the orthopaedic surgery department for the treatment of a bilateral humerus fracture. Cognitive and mental functions of the patient were normal before admission. She started to receive oxycodone–acetaminophen four times a day and later oxycodone 10 mg twice a day (total dose of oxycodone 60 mg over 48 h) for pain control. Over the course of 3 days she became confused and later obtunded. Oxycodone was discontinued. She became more alert and was able to communicate with gestures. Neurological examination, however, showed anarthria and inability to swallow, chew, or move her lips and tongue on command. Comprehension was retained during the whole episode, a fact that was proved after recovery, as the patient remembered specific details and events that had occurred during the entire incident. No focal signs were observed. Corneal, gag and jaw reflexes were preserved. Reflexive buccofacial movements such as yawning or coughing were present. Limb praxis was normal and eye movements were intact. Deep tendon reflexes were weak and no pyramidal signs were elicited. Routine blood tests disclosed mild normocytic anaemia and chronic renal failure, with no change in her haemodynamic status. Infective and inflammatory screens were negative. Computed tomography of the brain showed moderate to severe brain atrophy and bilateral subcortical lacunar lesions. These findings were similar to those observed 1 year earlier. No evidence of a new subcortical infarction was seen. The electroencephalograph (EEG) showed continuous rhythmic delta activity mixed with sharp waves and long periods of spike and wave ictal discharges (fig 1, left panel), consistent with NCSE. Intravenous valproic acid was initiated. Regular haemodialysis was continued. During the next few days she was able to initiate speech, move her tongue and bucco‐oral muscles. She progressively regained her ability to swallow. On EEG performed 24 h after initiation of treatment, the spiky activity seen earlier had disappeared. Diffuse slowing of the background with gradual improvement was observed over a few days. An EEG performed 9 days later was normal (fig 1, right panel).

Figure 1 Left panel: electroencephalograph (EEG), recorded during the florid phase of the opercular syndrome, shows diffuse slow‐wave activity and generalised repetitive synchronous sharp‐wave complexes. Right panel: 9 days later, the EEG shows a 9–10 Hz background rhythm and disappearance of the sharp‐wave complexes.

Two weeks after admission, owing to complete recovery, the treatment for epilepsy was gradually discontinued. Since then, the patient's neurological status and repeated EEGs have been normal.

Discussion

The clinical signs in this patient were consistent with FCMS. This condition, which may be congenital or acquired, persistent or intermittent, includes severe anarthria, loss of voluntary muscular functions of the face and tongue, and impaired mastication and swallowing, with preservation of reflex and autonomic functions.1 The aetiology of FCMS is heterogeneous: vascular insults in adulthood, such as bilateral subsequent strokes; infections of the CNS, such as herpes simplex encephalitis or acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. FCMS can be congenital, owing to bilateral dysgenesis of the perisylvian region. FCMS as a manifestation of epilepsy has been described nearly exclusively in childhood.2,3

The clinical picture of our patient was initially attributed to an overdose of oxycodone. Only consciousness and not the facial, pharyngeal and lingual and mastication movements, however, improved with discontinuation of the treatment. Uraemic aetiology could not be implicated, as there was no change in the renal status during the whole episode because the patient was regularly haemodialysed.

NCSE was diagnosed only by EEG, which showed an electroencephalographic pattern compatible with the diagnosis. NCSE seems to be associated with a high mortality and morbidity, justifying aggressive treatment.

Oxycodone hydrochloride is an opiate derivative. Oxycodone and its metabolites are excreted primarily through the kidneys. In cases of renal failure, precautions should be taken to avoid an overdose that can be reached at lower doses.4 Impaired consciousness, stupor, coma and seizures are all described as side effects of this drug, especially in the case of overdose or intoxication. In our case, the addition of oxocodone–acetaminophen may have caused an additive CNS depression,4 lowering the threshold for epileptic activity, in a patient at risk because of the underlying silent CNS pathology. Treatment for epilepsy reversed both the clinical opercular signs and the abnormal EEG recordings. Our case recommends exercising caution in the use of oxycodone in patients undergoing dialysis.4

The association of an opercular syndrome with an NCSE in an adult patient is highly unusual. In their report on three cases of opercular syndrome, Thomas et al2 describe an adult patient with myoclonic status epilepticus. Surface EEG, however, showed no evidence of cortical epileptic activity. The aetiology of these cases was either vascular or tumoral. Sasaguri et al5 described a patient with epilepsy, with a corpus callosum defect, who developed FCMS at the age of 27 years. In this case, however, FCMS was due to chronic herpes simplex encephalitis.

FCMS has only rarely been described as a manifestation of epileptic activity, and has been explained as a para‐ictal phenomenon, similar to the Landau–Kleffner syndrome by Shafrir and Prensky.3

The present case should draw attention to the possibility that an opercular syndrome in an adult may be due to NCSE and that in instances of FCMS the possibility of reversible (treatable) electrical activity should be ruled out.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mrs F Hedri, R Liebeskind, H Pollack and R Biton for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Informed consent was obtained for publication of the patient's details in this report.

References

- 1.Weller M. Anterior opercular cortex lesions cause dissociated lower cranial nerve palsies and anarthria but no aphasia: Foix‐Chavany‐Marie syndrome and “automatic voluntary dissociation” revisited. J Neurol 1993240199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas P, Borg M, Suisse G.et al Opercular myoclonic‐anarthric status epilepticus. Epilepsia 199536281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shafrir Y, Prensky A L. Acquired epileptiform opercular syndrome: a second case report, review of the literature, and comparison to the Landau‐Kleffner syndrome. Epilepsia 1995361050–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anon. Bradley W G, Daroff R B, Fenichel G M, Jankovic J. Drug database. In: eds. Neurology in clinical practice. Electronic edition. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2005, http:// www.nicp.com/ (accessed 1 Sep 2005)

- 5.Sasaguri H, Sodeyama N, Maejima Y.et al Slowly progressive Foix–Chavany–Marie syndrome associated with chronic herpes simplex encephalitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 200273203–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]