Abstract

Background

The use of self‐report measurements in clinical settings has increased. The underlying assumption for self‐report measurements is that the patient understands the questions fully and is able to give a reliable assessment of his or her own health status. This might be problematic in patients with limitations that interfere with reliable self‐assessment such as cognitive impairment or serious mood disturbances, as may be the case in multiple sclerosis. In these situations proxies may provide valuable information, provided we can be certain that proxies and patients give consistent ratings.

Objective

To examine whether patients with multiple sclerosis and their partners agree on the impact of multiple sclerosis on the daily life of the patient by using the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS‐29).

Methods

59 patients with multiple sclerosis and their partners completed the MSIS‐29. Agreement was examined, comprehensively at scale score levels and item functioning, using both traditional and less conventional psychometric methods (Rasch analysis).

Results

Agreement between patients and partners was good for the physical scale, and slightly less but still adequate for the psychological scale. Mean directional differences did not show considerable systematic bias between patients and proxies. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) satisfied the requirements for agreement, but were higher for the physical scale (0.81) than for the psychological scale (0.72). These findings were supported by Rasch analyses.

Conclusion

In this sample, albeit small, partners provided accurate estimates of the impact of multiple sclerosis. This supports the value of self‐rating scales and indicates that partners might be useful sources of information when assessing the impact of multiple sclerosis on the daily life of patients.

Health status assessment is becoming an increasingly important component of clinical research and findings often play an important part in medical decision making. Data collection is mainly carried out by self‐report questionnaires, and the patients themselves are considered to be the most appropriate source of information regarding their own health status.1 When regarding patients as the gold standard, we assume that they are able to give a reliable assessment of their health status. Consequently, this method of data collection may be less suitable for patients with insufficient communication or cognitive abilities. Furthermore, emotional factors may interfere with self‐assessment of physical health status, which may affect reliability. Applying self‐report measurements in these patients could lead to biased or unreliable information or loss of information.1,2 Therefore, existing general health status measures should be used with caution in patients experiencing these situations. However, it is precisely in these situations that we are most interested in assessing health status. A recent Health Technology Assessment report supported by the National Health Services in the UK carried out a systematic research of all existing literature to identify the general health status measures that have been validated in patients with cognitive impairment due to acquired brain injury, explicitly including multiple sclerosis.3 One of their suggestions for future research is that in these situations the use of proxies (eg, partners, relatives or close friends) to assess the situation of the patient should be considered. They emphasise that health status measures first need to be validated for use by proxies in certain populations and that the instrument should be assessed for patient–proxy agreement. In multiple sclerosis, both cognitive decline and severe mood disturbances may be present during the course of the disease.4,5 Several self‐report measurements have been developed to assess impairment and disability in multiple sclerosis. Of all available self‐report measurements, the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS‐29) is both disease specific and rigorously evaluated for its psychometric properties.6,7,8 Although there have been several populations in which proxy measurements have been investigated, such as the elderly, patients with stroke, patients with cancer and patients with Alzheimer's disease, little is known about the use of proxy respondents in multiple sclerosis.9,10,11,12,13,14,15 To examine the value of the use of proxies in multiple sclerosis, it is important to know to what level proxies can accurately assess the impact of multiple sclerosis on the daily life of the patient. The accuracy of proxy ratings is determined by the extent to which proxy ratings correspond to those provided by patients themselves.1,16 A psychometric evaluation of the MSIS‐29, when used by proxies, was carried out previously and the results were supportive towards using the MSIS‐29 in a proxy sample.17

This study aimed to examine the extent to which proxy ratings on the MSIS‐29 correspond to those provided by patients themselves.

Methods

Study sample

Patients with multiple sclerosis and their partners were recruited from an ongoing study at the outpatient clinic at the VU University Medical Centre (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). This study also included healthy controls. If the control person was the partner of the patient, he or she was asked to participate in this study on proxy measurements.

The medical ethical committee of the VU University Medical Centre approved the study protocol. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures and procedures

The impact of multiple sclerosis on daily life was assessed by means of the MSIS‐29. The MSIS‐29 is a 29‐item self‐report measurement, which assesses the physical and psychological effects of multiple sclerosis. These scales consist of 20 items and 9 items, respectively (box). Scores on the individual items are added and transformed to a 0–100 scale, thereby generating two summary scores of both scales. Higher scores indicate worse health.6 For this study the Dutch version of the MSIS‐29 was used, which is an in‐house translation of the original English version that was subsequently validated in a large study across eight European countries.18 Patients with multiple sclerosis and their partners were asked to complete this questionnaire. Both groups were assessed on the same day and independently of each other. The partners completed a modified version of the MSIS‐29 in which all items were phrased in the third person. They were instructed to view the situation from the perspective of the patient and complete the MSIS‐29 keeping in mind the following question: “How do you think the patient experiences the impact of multiple sclerosis on his/her life?”

Data on cognitive performance of the patients were collected using the brief repeatable battery of neuropsychological tests (BRB‐N).4 The BRB‐N is a test battery consisting of five tests, each measuring a different area of cognitive functioning, including verbal learning and memory, visuospatial learning, attention and concentration, information processing and semantic oral fluency.19 Mood status was assessed by means of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).20 The Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) and the multiple sclerosis subtype were available for all patients.21,22

Data analyses

For comprehensive evaluation of agreement, two complementary statistical approaches were applied: traditional methods and Rasch analyses.

Possible factors that could influence patient–proxy agreement were also examined.

Both the traditional analyses and the Rasch analyses were carried out for the physical and the psychological scales of the MSIS‐29.

Traditional methods

Agreement at the scale score level

Firstly, both absolute and directional mean differences between the two groups were calculated. The absolute mean difference, which is irrespective of direction, can be used as an indicator of agreement.23 The mean directional difference, on the other hand, is an indicator of possible systematic bias.24 Systematic bias can occur when proxies consistently report a lower or higher impact of multiple sclerosis than the patients themselves. In this case there can still be an excellent correlation between the two groups but a poor agreement.25 Paired Student's t tests were used to see whether the mean directional differences were significantly different from zero and thereby confirm the systematic bias.24,26 The magnitude of possible systematic bias can be estimated by standardising the mean differences to their standard deviations (mean directional difference/SD of difference). As this method is similar to calculating impact sizes (d) used in paired t tests, it seems reasonable to apply the same classification: d = 0.20 indicates a small bias, d = 0.50 indicates a moderate bias, d = 0.8 indicates a large bias.27

Items of the MSIS‐29 for the physical and psychological scales

Physical scale

In the past two weeks, how much has your multiple sclerosis limited your ability to…

Do physically demanding tasks?

Grip things tightly (eg, turning on taps)?

Carry things?

In the past two weeks, how much have you been bothered by…

Problems with balance?

Difficulties moving about indoors?

Being clumsy?

Stiffness?

Heavy arms and/or legs?

Tremor of the arms or legs?

Spasms in your limbs?

Your body not doing what you want it to?

Having to depend on others to do things for you?

Limitations in your social and leisure activities at home?

Being stuck at home more than you would like?

Difficulties in using your hands in everyday tasks?

Having to cut down the amount of time you spend on work or other daily activities?

Problems using transport (eg, car, bus, train or taxi)?

Taking longer to do things?

Difficulties doing things spontaneously (eg, going out on the spur of the moment)?

Needing to go to the toilet urgently?

Psychological scale

In the past two weeks, how much have you been bothered by…

Feeling unwell?

Problems sleeping?

Feeling mentally fatigued?

Worries related to your multiple sclerosis?

Feeling anxious or tense?

Feeling irritable, impatient or short tempered?

Problems concentrating?

Lack of confidence?

Feeling depressed?

Secondly, the correlation between ratings of patients and partners was examined using two‐way random ICCs. ICCs are preferable to Pearson's correlation coefficients, as an ICC accounts for systematic mean differences and this will give a chance corrected index of agreement at the individual level.24,28 Standards for interpreting ICC values are arbitrary, but we can apply the standard reliability criteria of >0.70 meaning “adequate” and >0.80 meaning “is preferred”.24,29,30

Agreement at the item level

Agreement at the item level was examined by calculating the percentages of exact agreement and global agreement between patient–proxy pairs. Exact agreement is the percentage of patient responses identical to the responses of proxy (eg, both patient and proxy score 1 on item 12). Global agreement refers to the percentage of agreement in one response category in both directions (eg, patient score 2 on item 12 and the proxy scores 1, 2 or 3 on this item).24

The patterns of (dis)agreement at item level were visualised to determine whether these would vary between patients and partners as a function of the impact of multiple sclerosis. The differences between each patient–proxy pair were plotted against the mean score on the MSIS‐29. The horizontal line through the zero ordinate shows perfect agreement between patients and their partners. A score above the zero line indicates that the partner has a higher score on the MSIS‐29 than the patient. A score below this line indicates that the patient scored higher on the MSIS‐29.31

Rasch analysis

Besides the more conventional ways of looking at agreement the data were also evaluated with the Rasch model, using the Rasch analysis package RUMM2020.32 Rasch analysis has the advantage of enabling the assessment of agreement at both the scale and item levels. This is because a Rasch analysis of rating scale data generates, among other things, two important statistics: a person location and an item location. The person location is an estimate of the person's disability. The item location is an estimate of the item's difficulty.33,34

We examined agreement at the MSIS‐29 scale score level to determine the extent to which patient–partner couples agreed on the physical and psychological effects of multiple sclerosis on the patient. Here we plotted person locations generated by the Rasch analysis of patients' MSIS‐29 responses against the person locations generated by the Rasch analysis of proxy MSIS‐29 responses.

We examined agreement at the item level to determine the extent to which patient–partner couples agreed on the difficulty of each item. To do this we plotted the locations of the individual items generated by Rasch analysis of the patient and proxy data.

Factors affecting agreement between patients and partners

Different variables that could have an influence on agreement were investigated. These variables included: cognition, mood and disability of the patient and sex of the proxy. For each variable the sample was divided into different subgroups, according to variable‐specific criteria. Subsequently, the mean directional differences between patients and proxies were calculated for the corresponding MSIS‐29 scores in each subgroup. Analyses of variance were carried out to see if these subgroups differed considerably from each other. In addition, ICCs for each subgroup were calculated.

The EDSS score of the patient was classified as follows: 0.0–3.5; 4.0–6.0; 6.5–8.0. The possible influence of mood was investigated by dividing the sample into subgroups defined on the HADS score. The following criteria were used: ⩽7 = no clinical levels of anxiety and depression; 8−10 = clinically borderline; ⩾11 = clinically definite levels of anxiety and depression.35 To investigate the influence of cognitive functioning, the sample was divided into three subgroups: normal BRB‐N scores, 1 or 2 abnormal BRB‐N scores, and 3 or more abnormal BRB‐N scores. Cognitive dysfunction on one of the tests was defined as 1 SD below the mean reported for healthy subjects.36 Finally, the sample was divided according to sex of the proxy.

Results

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the patients and proxies, the total scores on the physical and psychological scales of the MSIS‐29, and the number of patients in each subgroup of the EDSS, the HADS and the BRB‐N.

Table 1 Characteristics of patients and proxies.

| Patients | Proxies | |

| Total | 59 | 59 |

| Female (n) | 41 | 19 |

| Age (years)* | 48 (8.9) | 49 (9.0) |

| Years since MS onset* | 13 (7.2) | — |

| Type of MS (n) | ||

| Relapsing–remitting | 25 | — |

| Secondary progressive | 21 | — |

| Primary progressive | 11 | — |

| Other | 2 | — |

| MSIS‐29 | ||

| Physical scale* | 42.1 (24.1) | 42.9 (25.8) |

| Psychological scale* | 29.0 (22.6) | 33.3 (22.6) |

| EDSS | ||

| 0.0–3.5 | 18 | — |

| 4.0–6.0 | 30 | — |

| 6.5–8.0 | 11 | — |

| HADS (depression/anxiety) | ||

| ⩽7 | 42/37 | — |

| 8–10 | 7/10 | — |

| ⩾11 | 10/12 | — |

| BRB‐N | ||

| 0 abnormal scores | 17 | — |

| 1–2 abnormal scores | 23 | — |

| ⩾3 abnormal scores | 17 | — |

| Missing | 2 | — |

BRB‐N, Brief Repeatable Battery of Neuropsychological tests; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; MS, multiple sclerosis; MSIS‐29, Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale.

*Values are mean (SD).

Patient–proxy agreement for the physical scale

Agreement at the scale score level

Table 2 shows the results of the traditional analyses on agreement between patients and their partners. The absolute mean difference of the physical scale was 10.0 (11.6). The mean directional difference on the physical score was minimal (0.8 (15.3)) and there was no evidence of systematic bias (d = 0.1). The ICC showed good agreement (0.81).

Table 2 Patient‐proxy agreement on the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale at the scale score and item levels.

| MSIS‐29 | Scale score level | Item level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute difference (Mean (SD)) | Directional difference* (Mean (SD)) | p Value | d | ICC | Exact agreement (%) | Global agreement (%) | |

| Physical scale score | 10.0 (11.6) | 0.8 (15.3) | 0.679 | 0.1 | 0.81 | 47.4 | 83.1 |

| Psychological scale score | 13.1 (11.6) | 4.4 (17.0) | 0.054 | 0.3 | 0.72 | 44.6 | 82.5 |

d, impact size; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; MSIS‐29, Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale.

*Proxy minus patient; positive scores indicate the proxy scores are higher than the patient scores.

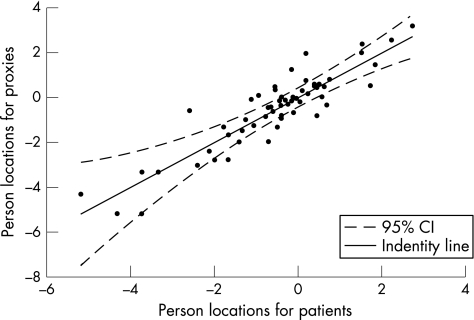

Figure 1 displays the locations of the individual patient–partner couples for the physical scale, which were generated by Rasch analysis. The identity line shows perfect agreement between the individual patient–partner couple on the physical impact of multiple sclerosis on daily life. Values on this line show that the patient–partner couple had the same score on the physical scale. Values above this line indicate that proxies had a higher score on the physical scale and values below this line indicate that proxies had a lower score than the patients. Reliability analysis of the person locations for patients and proxies showed an ICC of 0.90.

Figure 1 Person locations for patients and proxies on the physical scale. CI, confidence interval.

Agreement at the item level

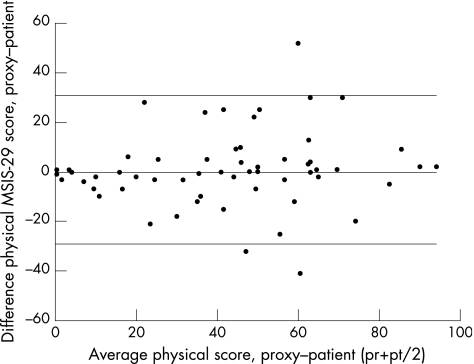

An exact agreement of almost 50% was seen between patients and proxies (table 2). Figure 2 illustrates the agreement between patients and their partners as a function of the average of each pair of scores. The scatter plots of the physical MSIS‐29 score show the largest disagreement at a score of 60 on the MSIS‐29. Smaller differences were found at the lower levels of impact of multiple sclerosis.

Figure 2 Differences between proxies and patients for the physical scale score. MSIS‐29, Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale; pr, proxy physical scale score; pt, patient physical scale score.

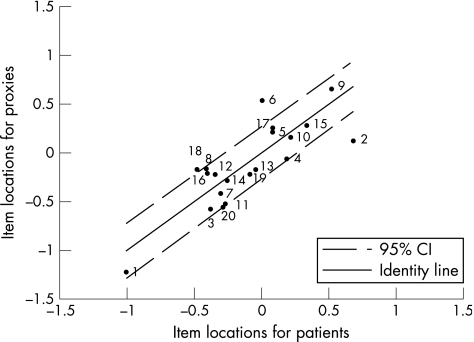

The item locations of patients plotted against the item locations of the proxies for the physical scale, which were generated by Rasch analysis, are shown in fig 3. The identity line shows perfect agreement on the difficulty of items. All items, with exception of items 2, 6 and 18, are located within the 95% confidence interval (CI).

Figure 3 Item locations for patients and proxies on the physical scale. CI, confidence interval.

Patient–proxy agreement for the psychological scale

Agreement at the scale score level

Scores on the psychological scale show a slightly larger absolute mean difference of 13.1 (11.6) (table 2). The mean directional difference for the psychological scale (4.4 (17.0)) showed a tendency for systematic bias with a p value of 0.054. The magnitude of the difference between scores on this scale was moderate: d = 0.3. The ICC of 0.72 was lower than that for the physical scale, but this is still classified as adequate agreement.29

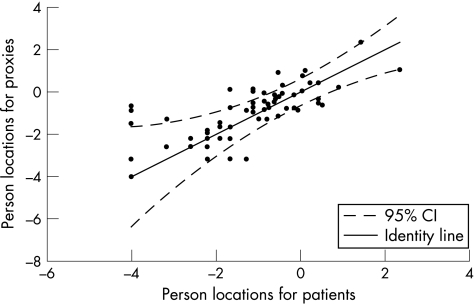

The person locations of the individual patient–partner couples for the psychological scale generated by Rasch analysis are shown in fig 4. Again, the identity line represents perfect agreement between the individual patient–partner couple on the psychological impact of multiple sclerosis on the daily life of the patient. Reliability analysis of the person locations for patients and proxies gave an ICC of 0.71.

Figure 4 Person locations for patients and proxies on the psychological scale. CI, confidence interval.

Agreement at the item level

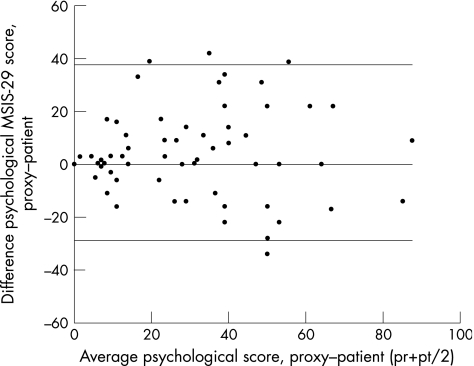

Exact and global agreement on the psychological scale was 44.6% and 82.5%, respectively (table 2). In comparison with the scatter plot of the physical scale, the scatter plot of the psychological scale showed larger disagreement in the lower categories of the MSIS‐29 (fig 5).

Figure 5 Differences between proxies and patients for the psychological scale score. MSIS‐29, Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale; pr, proxy psychological scale score; pt, patient psychological scale score.

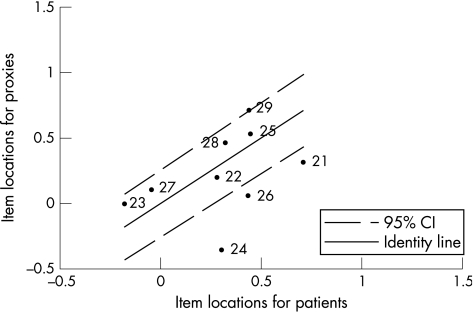

Figure 6 shows the item locations of patients plotted against the item locations of the proxies for the psychological scale, which were generated by Rasch analysis. Six of the nine psychological items were located inside the 95% CI. The largest disagreement on item difficulty was seen for item 24. The item locations of the psychological scale are positioned in the higher item location region when compared with the item location of the physical scale.

Figure 6 Item locations for the physical scale for patients and proxies. CI, confidence interval.

Factors affecting agreement between patients and partners

Analysis of variance showed no considerable differences between the three subgroups of the EDSS. Results did show a decrease in ICC when the EDSS increased (EDSS 0.0–3.5 the ICC was 0.78 for both scales; EDSS 4.0–6.0, the ICC was 0.64 for both scales; and EDSS 6.5–8.0, the ICC was 0.74 for the physical scale and 0.27 for the psychological scale).

The subgroups of the HADS showed no significant differences between the mean directional differences for patients and proxies and ICCs remained constant.

No significant differences were seen between the subgroups of the BRB‐N scores. ICCs >0.80 were seen in the group of normal BRB‐N scores. Slightly lower ICCs were seen in the groups with abnormal BRB‐N scores.

Moderate systematic bias was seen on the psychological scale of the MSIS‐29 for female proxy respondents (8.37 (17.1), p = 0.047, d = 0.5).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the accuracy of proxy ratings on impact of multiple sclerosis. This could be important in situations when patients might not be able to provide reliable information about their health status owing to communication problems, cognitive dysfunction or emotional problems. To use proxies instead of patients, proxy ratings need to be reliable and therefore accurate. The accuracy of proxy ratings is determined by the extent to which they agree with responses provided by patients themselves.

Agreement between responses on both scales of the MSIS‐29 was investigated by means of several statistical methods, both traditional and less conventional (Rasch analyses). There have been few comparisons between these two methods and it is important to know whether they tend to similar conclusions.

Results on the physical scale showed that on the group level the mean directional difference was very small, indicating that systematic bias was not present. Intraclass correlations showed good agreement. Both exact agreement and global agreement were high. These findings are in concordance with several other studies investigating agreement on health status. Good agreement on the physical impact of disease can be explained by the fact that physical health is relatively easy to observe for the proxy.1,2,9 These findings were supported by Rasch analyses. Agreement on the physical scale score showed an ICC of 0.90, which implies that patients and proxies come to similar conclusion about the impact of multiple sclerosis on the daily life of the patient. Nevertheless, substantial individual differences may be encountered. Agreement on item level displayed that, with the exception of three, all items were located within the 95% CI. This indicates that proxies and patients come to similar conclusion about the difficulty of the items on the physical scale. This also provides evidence to support the stability of the MSIS‐29. However, these results do not exclude the possibility of finding relevant differences on certain items between patients and proxies (figs 2,5).

The data showed slightly larger disagreement on the psychological scale. Absolute and directional mean differences on group level were larger than those on the physical scale and systematic bias was moderate. These findings are consistent with proxy measurements obtained earlier from other patients' samples. Proxies tend to be less accurate than patients when it comes to the more subjective, less observable questions.1,2,9,15,37 The scatter plot of the psychological scale shows larger disagreement in the lower MSIS‐29 score regions in comparison with the scatter plot of the physical scale. Intraclass correlations were lower, but still satisfied published requirements for inter‐rater reliability. Exact and global agreements were slightly lower than on the physical scale. The findings on the psychological scale were also supported by Rasch analyses. Lower but adequate agreement was seen on the psychological scale score, with an ICC of 0.71. At the item level of the psychological scale Rasch analysis showed that, with the exception of three items, all items were located in the 95% CI, indicating statistically adequate agreement about item difficulty. The lack of agreement for these three items indicates that patients and proxies differ on the difficulty of the item. The source of this disagreement is hard to define, but may be related to differences in the interpretation of the item.

Several factors that could possibly influence patient–partner agreement were examined. An impact of disability on the agreement on the psychological scale was noted; an increase in EDSS score resulted in a decrease of the ICC on the psychological scale. Lower patient–proxy agreement for patients with higher physical disability was also seen in other studies.23,38 In contrast with male proxy respondents, female proxy respondents seemed to consistently overestimate the psychological impact of multiple sclerosis. However, there is no consensus regarding influence of sex on agreement, and our finding should therefore be considered with caution. Other evaluated factors (cognition and mood) did not seem to influence agreement.

In general, our findings show that the agreement between patients and proxies was good on both scales, although agreement on the physical scale was slightly higher than on the psychological scale. It should be noted that the findings of this study are based on the use of partners as proxies. Whether these results are also applicable on other proxies, such as healthcare providers, remains to be investigated. A limitation of this study is the small sample size. This resulted in even smaller groups of patients who had cognitive problems and mood disturbances. The finding that cognitive functioning and mood did not seem to influence the agreement should therefore be interpreted with caution. Future research focusing on proxy measurements in larger or more cognitively impaired patient samples is needed.

In conclusion, taking the limitations into account, this study shows that the agreement on the physical and the psychological effects between patients and their partners when using the MSIS‐29 was adequate and that proxies might be useful sources when assessing the impact of multiple sclerosis. Moreover, the good agreement between proxies and patients supports the value of self‐rating scales in clinical research.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients and their partners who participated in this study. The Multiple Sclerosis Centre of the VU University Medical Centre is partially funded by a programme grant from the Dutch Multiple Sclerosis Research Foundation.

Abbreviations

BRB‐N - brief repeatable battery of neuropsychological tests

EDSS - Expanded Disability Status Scale

HADS - Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

ICC - intraclass correlation coefficient

MSIS‐29 - Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Sprangers M A, Aaronson N K. The role of health care providers and significant others in evaluating the quality of life of patients with chronic disease: a review. J Clin Epidemiol 199245743–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andresen E M, Vahle V J, Lollar D. Proxy reliability: health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) measures for people with disability. Qual Life Res 200110609–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riemsma R P, Forbes C A, Glanville J M.et al General health status measures for people with cognitive impairment: learning disability and acquired brain injury. Health Technol Assess 200151–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao S M, Leo G J, Bernardin L.et al Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. I. Frequency, patterns, and prediction. Neurology 199141685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssens A C, van Doorn P A, de Boer J B.et al Anxiety and depression influence the relation between disability status and quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 20039397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hobart J C, Riazi A, Lamping D L.et al Improving the evaluation of therapeutic interventions in multiple sclerosis: development of a patient‐based measure of outcome. Health Technol Assess 200481–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson A J, Hobart J C. Multiple sclerosis: assessment of disability and disability scales. J Neurol 1998245189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riazi A, Hobart J C, Lamping D L.et al Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS‐29): reliability and validity in hospital based samples. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 200273701–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein A M, Hall J A, Tognetti J.et al Using proxies to evaluate quality of life. Can they provide valid information about patients' health status and satisfaction with medical care? Med Care 198927(Suppl)S91–S98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumann P J, Araki S S, Gutterman E M. The use of proxy respondents in studies of older adults: lessons, challenges, and opportunities. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000481646–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sneeuw K C, Aaronson N K, Osoba D.et al The use of significant others as proxy raters of the quality of life of patients with brain cancer. Med Care 199735490–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinberger M, Samsa G P, Schmader K.et al Comparing proxy and patients' perceptions of patients' functional status: results from an outpatient geriatric clinic. J Am Geriatr Soc 199240585–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sneeuw K C, Sprangers M A, Aaronson N K. The role of health care providers and significant others in evaluating the quality of life of patients with chronic disease. J Clin Epidemiol 2002551130–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novella J L, Jochum C, Jolly D.et al Agreement between patients' and proxies' reports of quality of life in Alzheimer's disease. Qual Life Res 200110443–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothman M L, Hedrick S C, Bulcroft K A.et al The validity of proxy‐generated scores as measures of patient health status. Med Care 199129115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sneeuw K C, Aaronson N K, Sprangers M A.et al Value of caregiver ratings in evaluating the quality of life of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 1997151206–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Linden F A, Kragt J J, Klein M.et al Psychometric evaluation of the multiple sclerosis impact scale (MSIS‐29) for proxy use. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005761677–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hobart J C, Cano S, O'Conner R, Kinos S.et al Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale‐29 (MSIS‐29): measurement stability across eight European countries. Mult Scler 20039(Suppl 1)23 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boringa J B, Lazeron R H, Reuling I E.et al The brief repeatable battery of neuropsychological tests: normative values allow application in multiple sclerosis clinical practice. Mult Scler 20017263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers P P.et al A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med 199727363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurtzke J F. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983331444–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lublin F D, Reingold S C. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of New Agents in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology 199646907–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sneeuw K C, Aaronson N K, Sprangers M A.et al Comparison of patient and proxy EORTC QLQ‐C30 ratings in assessing the quality of life of cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol 199851617–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee J, Koh D, Ong C N. Statistical evaluation of agreement between two methods for measuring a quantitative variable. Comput Biol Med 19891961–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson L M, Longstreth W T, Jr, Koepsell T D.et al Proxy respondents in epidemiologic research. Epidemiol Rev 19901271–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall G N, Hays R D, Nicholas R. Evaluating agreement between clinical assessment methods. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 19944249–257. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen J.Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 198819–74.

- 28.Shrout P E, Fleiss J L. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 197986420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nunnally J C, Bernstein I H.Psychometric theory. 3rd edn. New York: McGraw‐Hill, 1994

- 30.Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcomes Trust Assessing health status and quality‐of‐life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res 200211193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bland J M, Altman D G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 19861307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andrich D, Sheridan B E, Luo G.RUMM2020: Rasch Unidimensional Measurement Models (version 4.0). Perth, Western Australia: RUMM Laboratory, 2004

- 33.Conrad K J, Smith E V., Jr International conference on objective measurement: applications of Rasch analysis in health care. Med Care 200442(Suppl)S1–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrich D. Controversy and the Rasch model: a characteristic of incompatible paradigms? Med Care 200442(Suppl)S7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zigmond A S, Snaith R P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 198367361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Achiron A, Barak Y. Cognitive impairment in probable multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 200374443–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Magaziner J, Simonsick E M, Kashner T M.et al Patient‐proxy response comparability on measures of patient health and functional status. J Clin Epidemiol 1988411065–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sneeuw K C, Aaronson N K, de Haan R J.et al Assessing quality of life after stroke. The value and limitations of proxy ratings. Stroke 1997281541–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]