Abstract

Background

The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) requires caregivers to rate decline in patients' cognitive and functional performance and has never been used for mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Methods

We contrasted the discriminative and predictive power of the IQCODE with that of the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and a verbal episodic memory measure, the Rey's Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT), in 45 patients with MCI (mean (SD) age at baseline: 71.6 (4.7) years) and 30 outpatients with dementia (70.5 (6.3) years) attending the Neuropsychology Service, St Gerardo Hospital, and compared them with 55 cognitively intact elderly people (70.7 (7.1) years). Patients with MCI were followed up for at least 2 years or until conversion to dementia.

Results

In total, 24 patients with MCI (53.3%) had converted to dementia at follow up (mean (SD) duration of follow up 17.0 (7.3) months for converters and 35.0 (7.1) months for non‐converters). At baseline, the ability to differentiate patients with MCI from healthy controls was similar for the IQCODE (area under the curve (AUC) 0.86) and the MMSE (AUC 0.84; z = 0.53, not significant). As predictors of conversion to dementia, a trend favouring the IQCODE (AUC 0.86) with respect to immediate (AUC 0.74) and delayed (AUC 0.75) recall on the RAVLT was apparent (z = 1.36, p = 0.087 versus immediate recall, z = 1.51, p = 0.064 versus delayed recall). The independent predictive ability of IQCODE and memory scores was evaluated through logistic regression, and the questionnaire alone yielded the best correct classification of 81%.

Conclusions

The IQCODE is an informant based measure of cognitive decline that may provide a relevant contribution to the diagnostic and prognostic investigation of patients with MCI.

Keywords: mild cognitive impairment, IQCODE, informant‐based instruments, dementia, neuropsychology

Latest recommendations on the investigation of preclinical dementia stress the importance of assessing cognitive decline rather than impairment, and suggest the validity of informant reports as an index of decline.1 In the field of neuropsychology, efforts to identify subjects with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and to estimate their risk of conversion to dementia have mainly focused on the search for a direct measure of current cognitive status that is sensitive enough to detect minor impairments, with memory tests usually showing the best discriminative and predictive power, at least for the amnestic forms of MCI.2,3 Informant based instruments have received less attention. Despite some obvious disadvantages (such as the need for a collateral source), scales and questionnaires for caregivers have repeatedly demonstrated their validity for the screening of dementia (see Jorm4 for a meta‐analysis on this issue), and when challenged with mild stages of cognitive deterioration. The CAMDEX informant interview,5 the Clinical Dementia Rating scale,6,7,8 the Brief Cognitive Scale,9 the Functional Activities Questionnaire10 and the Global Deterioration Scale11 have shown satisfactory discriminative and predictive ability in the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease (AD). As well as accuracy, scales for caregivers also display a series of strengths with respect to neuropsychological tests,4,12 such as more direct correspondence with everyday functioning, independence from educational and premorbid intellectual level, better tolerability for patients, and applicability to non‐compliant or non‐testable cases.

Of the informant based tools, the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE)13 is one of the most well known and widely used. It comprises 26 self administered items and requires relatives or friends to compare the patient's current cognitive and functional performances in everyday life with their level of functioning 10 years previously. A meta‐analysis of studies comparing the IQCODE with the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)14 showed that the two scales have equivalent effectiveness at screening for dementia, with sensitivity and specificity values ranging from 69% to 89% and from 65% to 96%, respectively.4 Thanks to its “retrospective” character, the IQCODE presents the additional advantage of allowing assessment of cognitive and functional decline. However, the ability of an informant based instrument to discriminate patients with MCI from controls and to concomitantly predict likelihood of patients' conversion to dementia of both AD and non‐AD type has never been investigated.

In a previous exploratory study, we assessed the validity of the IQCODE in a small sample of patients with MCI, compared with normal elderly and patients with dementia, and achieved promising results.15 In the present investigation, we assessed the contribution of the IQCODE to the diagnostic and prognostic investigation in a larger sample, while comparing it with the discriminative and predictive power of two standards for the screening and prediction of dementia: the MMSE and an episodic verbal memory measure, the Rey's Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT),16 which has properties (verbal content, free recall, and delayed testing) that are deemed to be particularly sensitive to mild cognitive deficits.17

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Patients with MCI were selected from new outpatients attending our neuropsychology service from March 2000 to July 2003 for subjective cognitive disturbances or referred by their general practitioner or by a neurologist suspecting cognitive impairment, and newly receiving a diagnosis of MCI according to Petersen's outlines:18 self or informant's cognitive complaint, one or more abnormal score at psychometric assessment with respect to normative data, and no significant interference with activities of daily living. In addition to unavailability or actual lack of a compliant informant, exclusion criteria were: presence of serious medical illness or physical disability, past or present history of neurological or psychiatric disturbances (including stroke, extrapyramidal disorders, and severe depression), and substance misuse. After all data were collected, further selection was subsequently made according to the availability of adequate follow up data; eligible patients had to have been followed up for at least 2 years, or until a diagnosis of dementia had been reached.

Standardised diagnostic criteria for dementia from the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM‐IV)19 were applied for the selection of subjects to be included in the group with dementia (as well as for the classification of MCI converters) among outpatients of the neuropsychological service. Controls were healthy subjects taking part in our ongoing normative study of the Italian version of the IQCODE; they were male or female volunteers aged ⩾50 years. Clinical exclusion criteria were the same as for patients with MCI for both demented and healthy subgroups; controls also had to achieve a MMSE score ⩾24 after adjustment for demographic variables.20

Of the initial pool of 77 individuals meeting study inclusion and exclusion criteria for MCI, 18 (23.4%) could not be included because of inadequate follow up data, 10 (13%) because of lack of an informant, and 4 (5.2%) because of incomplete IQCODE protocols (defined as three or more answers missing from the 26 required in the questionnaire). Patients excluded did not differ from those enrolled in features such as age, education, and MMSE and memory scores (data not shown). The final study sample included 45 patients with MCI, 30 patients with dementia, and 55 normal controls. Enrolled patients had either degenerative (n = 36, 80%) or subcortical vascular (defined according to the outlines of Rockwood et al;21 n = 9, 20%) mild cognitive impairment. In total, 27 subjects (60%) were purely amnestic, 10 (22%) had memory deficits plus impairment in another cognitive domain, and 8 (18%) had impairment in a single or in multiple non‐memory domains. The group with dementia comprised 17 patients (56.6%) with AD, according to criteria from the NINDS‐ADRDA;22 5 (16.7%) with frontotemporal dementia (FTD), according to consensus criteria;23 3(10.0%) with mixed dementia; 2(6.7%) with subcortical vascular dementia (SVD), according to the modified criteria from NINDS‐AIREN for probable vascular dementia;24 and the remaining three subjects (10.0%) were classified as having dementia not otherwise specified (NOS).

The caregivers of the patients with MCI were 58.4% female, had a mean (SD) age of 52.3 (13.3) years (range 26–76) and a education of 10.7 (4.6) years (range 4–17). They were mostly spouses (44.5%, n = 20), children (40.0%, n = 18), siblings or in laws (6.7%, n = 3), or friends (4.4%, n = 2). For two subjects, (4.4%) the informant's relationship type was not registered. Over half (56%) lived with the patient. The caregivers of the patients with dementia were 63.1% female, with mean (SD) age of 53.7 (13.1) years (range 33–79) and education of 9.8 (4.0) years (range 5–17). They were mostly children (51.7%, n = 16), followed by spouses (37.9%, n = 11), and siblings or in laws (7.4%, n = 2). For one informant (3.0%), the relationship type was not registered, and 52% of caregivers lived with the patient.

Methods

We compared the ability of the IQCODE and the MMSE to discriminate patients with MCI from patients with dementia and age matched controls, and the ability of baseline IQCODE and RAVLT scores to predict progression from MCI to dementia.

At baseline, all patients underwent neurological and neuroradiological investigation, and performed an extensive psychometric battery including standardised tests for the evaluation of attention, verbal and visual episodic memory, language production and comprehension, visuospatial abilities, praxis, executive functions, and reasoning. Mood and behavioural disturbances were also assessed. Follow up of patients with MCI was carried out repeatedly, approximately every 12 months, according to our usual patient care schedule, with the same psychometric battery.

The IQCODE was administered only at baseline. It requires caregivers to rate changes that have possilbly occurred over the past 10 years in the patient's ability to cope with several everyday activities, on a scale from “much improved” (1 point) to “much worse” (5 points); a score of 3 is given for a “no change” judgment. Total score derives from averaging the ratings over the total number of completed items and ranges from 1.0 to 5.0, with higher scores indicating worse decline. Completion takes approximately 10 minutes. The questionnaire was filled in autonomously by informants after receiving appropriate instructions, while patients were undergoing neuropsychological assessment. At the end of the patient's testing session, scoring of the IQCODE was performed by an examiner (one psychology trainee) blinded to patients' data, after responses had been checked with the caregiver to ensure full comprehension and completion of questions.

The MMSE and the RAVLT immediate recall (sum of five learning trials) and delayed recall (translation and normative data which are available for use in the Italian population25) were administered as part of the neuropsychological assessments both at baseline and at follow up. These results were available to the clinician who made the diagnosis at baseline and who judged conversion at follow up, whereas the IQCODE scores were not.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (version 10.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Student's t test, χ2 analysis, and analysis of variance with pairwise post hoc comparisons were used to compare means of discrete and continuous variables among the study groups, with two tailed standard significance level set at p<0.05. Correlation analysis was carried out using Pearson's r coefficient.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to assess the accuracy of each instrument as a screen for mild cognitive impairment and as a predictor of transition to dementia. Areas under the curve (AUC) were compared using the method of Hanley and McNeil,26 considering a one tailed significance level of p<0.05. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of the instruments were also calculated at their best cut off points. Backward stepwise logistic regression analysis (conversion to dementia (yes/no) as dependent variable) was performed to establish the independent predictive ability of the IQCODE, the RAVLT immediate and delayed scores, and the demographic variables.

RESULTS

Comparisons between the sociodemographic and main neuropsychological features of the study groups are shown in table 1. No statistically significant difference in demographics was detected. The MMSE and IQCODE scores were significantly different for all study groups, with the worst performance shown by patients with dementia and intermediate values by patients with MCI.

Table 1 Comparison between demographic and baseline neuropsychological variables of the study groups.

| Normal (n = 55) | Dementia (n = 30) | MCI (n = 45) | MCI‐C (n = 24) | MCI‐NC (n = 21) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 70.7 (7.1) | 70.5 (6.3 | 71.6 (4.7 | 72.7 (4.0) | 70.3 (5.2) | |||||

| Men, n (%) | 25 (46) | 10 (33)‡ | 23 (51) | 9 (38)‡ | 14 (68) | |||||

| Education | 7.3 (3.5) | 6.5 (3.9) | 7.0 (3.0) | 6.7 (3.4) | 7.3 (2.5) | |||||

| Disease duration (months) | – | 25.5 (15.5) | 22.7 (14.4) | 22.2 (13.8) | 23.4 (15.6) | |||||

| MMSE | 28.9 (1.1) | 20.0 (5.2)* | 26.2 (2.6*)† | 25.6 (3.0)† | 27.0 (1.6)† | |||||

| IQCODE | 3.1 (0.2) | 4.1 (0.4)* | 3.6 (0.4)†* | 3.8 (0.4)†‡ | 3.3 (0.2)† | |||||

| RAVLT immediate recall | – | 13.2 (4.6) | 21.6 (6.7)† | 19.0 (5.5)†‡ | 24.7 (6.7)† | |||||

| RAVLT delayed recall | – | 0.7 (1.8) | 2.0 (1.8)† | 1.2 (1.4)‡ | 3.0 (2.1)† | |||||

| Attentional matrices | – | 28.5 (6.4) | 36.5 (5.9)† | 34.1 (5.5)† | 38.9 (6.8)† | |||||

| Letter verbal fluency | – | 15.9 (6.9) | 28.2 (5.3)† | 23.1 (4.4)†‡ | 31.1 (5.8)† |

Data are mean (SD), unless otherwise stated. *p<0.0001 v normal, †p<0.0001 versus patients with dementia, ‡p<0.001 versus non‐converters. MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MCI‐C, mild cognitive impairment converters; MCI‐NC, mild cognitive impairment non‐converters; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; RAVLT, Rey's Auditory Verbal Learning Test; IQCODE, Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly.

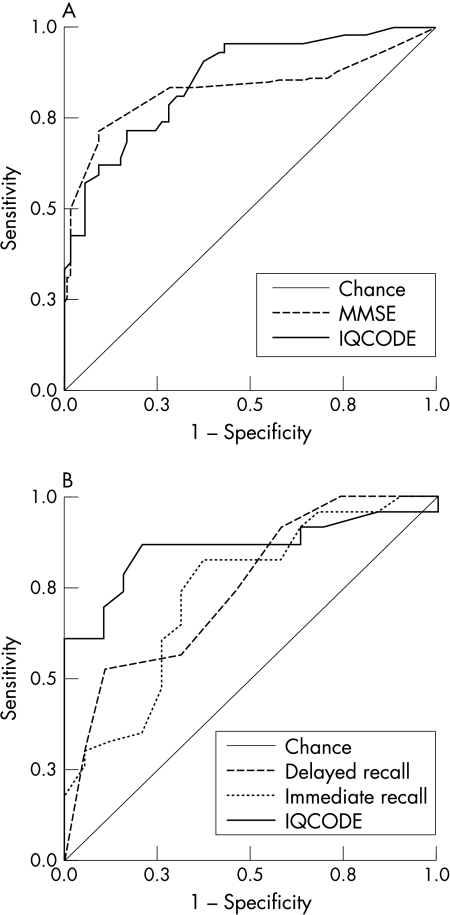

ROC curves for the MMSE and the IQCODE as measures for discriminating between patients with MCI and normal controls are shown in fig 1A. Areas under the curves were overlapping: 0.86 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78 to 0.93) for the IQCODE, 0.84 (0.73 to 0.92) for the MMSE (z = 0.53, p>0.05).

Figure 1 Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves for (A) the MMSE and the IQCODE as screening tests for mild cognitive impairment and (B) Rey's immediate and delayed recall and the IQCODE as predictors of progression from mild cognitive impairment to dementia.

Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values obtained at the best cut off points for the two screening tools are shown in table 2. Overall accuracy was 76% for the IQCODE and 77% for the MMSE.

Table 2 Sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predictive values for the MMSE and the IQCODE as screening tools for mild cognitive impairment and for Rey's immediate and delayed recall and the IQCODE as predictors of progression from mild cognitive impairment to dementia.

| Discriminative ability (MCI versus normals) | Predictive ability (MCI‐C versus MCI‐NC) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IQCODE* | MMSE† | IQCODE‡ | Immediate recall§ | Delayed recall¶ | |||

| Raw | Adjusted | Raw | Adjusted | ||||

| Sensitivity | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.75 |

| Specificity | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.57 |

| Positive PV | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.64 |

| Negative PV | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.65 |

Cut offs: *3.19/3.22; †28/29; ‡3.45/3.48. Raw/adjusted cut off: §22/23−29/30; ¶2/3−4.3/4.5. PV, predictive value; MCI‐C, mild cognitive impairment converters; MCI‐NC, mild cognitive impairment non‐converters; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; IQCODE, Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly.

At follow up, patients with MCI were subdivided into two groups, according to their clinical evolution: 24 subjects (53.3%) had converted to dementia (converters), while 21 (46.7%) had reverted to normal mental function (n = 6, 13.6%) or had remained with MCI (n = 15, 33.1%) (non‐converters). Of the converters, 12 (50.0%) met criteria for AD, 3 (12.5%) for SVD, 3 (12.5%) for FTD, 2 (8.3%) for mixed AD/SVD, and 4 (16.7%) had dementia NOS. Average (SD) follow up duration was 17.0 (7.3) months for converters and 35.0 (7.1) months for non‐converters

Comparison between sociodemographic and neuropsychological features of converters, non‐converters, and patients with dementia is shown in table 1. There was no statistically significant difference in age, education, and disease duration; non‐converters included a significantly larger percentage of men with respect to the other two groups. Baseline scores for MMSE and Attentional matrices from the MDB25 were significantly lower for demented than both MCI subgroups, while there was no difference between converters and non‐converters. Baseline RAVLT immediate recall, IQCODE, and verbal fluency scores were significantly different among the three groups, with the worst performance for patients with dementia and intermediate values for converters; baseline RAVLT delayed recall score was similar for patients with dementia and for converters and significantly lower with respect to non‐converters.

Logistic regression analysis performed on the MCI subgroup, with transition to dementia (yes/no) as dependent variable and including age, education, RAVLT immediate and delayed raw scores, and the IQCODE as predictors, showed that the questionnaire alone had the highest predictivity, resulting in an overall correct classification of 81% (36/45 subjects) (β = −4.506, Wald statistics = 10.394, p<0.001); all of the other variables were not retained in the final model.

ROC curves for RAVLT immediate and delayed raw scores and the IQCODE as measures predicting conversion from MCI to dementia are shown in fig 1B. Area under the curve was 0.86 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.98) for the IQCODE, 0.74 (0.58 to 0.89) for immediate recall, and 0.75 (0.60 to 0.90) for delayed recall; there was no statistically significant difference between the areas, although a trend favouring the IQCODE was apparent: z was 1.36 for the IQCODE compared with immediate recall (p = 0.087) and 1.51 for the IQCODE compared with delayed recall (p = 0.064).

Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values obtained at the best cut off points for the three measures are shown in table 2. Overall accuracy was 80% for the IQCODE, 73% for RAVLT immediate recall, and 67% for delayed recall.

“Predictive” ROC curves were also calculated for RAVLT adjusted scores: AUC was 0.70 (95% CI 0.54 to 0.86) for immediate recall and 0.75 (0.60 to 0.90) for delayed recall; there was a trend towards significance in favour of the IQCODE with respect to both RAVLT immediate (z = 1.58, p = 0.057) and delayed recall (z = 1.31, p = 0.095). Corresponding sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values obtained at the best cut off points are shown in table 2. Overall accuracy was 67% for immediate recall and 64% for delayed recall.

Correlation analysis was performed on the pool of patients with MCI for the IQCODE, MMSE, and RAVLT scores, considering patients' main demographic and clinical features. Results are displayed in table 3. The IQCODE was significantly correlated with the MMSE (p = 0.027), and RAVLT immediate (p = 0.004) and delayed (p<0.001) recall. It was also correlated with age (p<0.001), but not with education and disease duration; the same was true for RAVLT scores.

Table 3 Correlation between the IQCODE, the MMSE, and the RAVLT immediate and delayed recall scores with sociodemographic and clinical features of patients with MCI (n = 45).

| IQCODE | MMSE | Immediate recall | Delayed recall | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IQCODE | 1.0 | – | – | – | ||||

| MMSE | −0.39* | 1.0 | – | – | ||||

| Immediate recall | −0.45* | 0.24 | 1.0 | – | ||||

| Delayed recall | −0.59* | 0.45* | 0.70* | 1.0 | ||||

| Age | 0.55* | −0.15 | −0.39* | −0.39* | ||||

| Education | −0.25 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.17 | ||||

| Disease duration | −0.01 | −0.22 | 0.00 | −0.03 |

Pearson's r coefficients. *p<0.05. MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; IQCODE, Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown that the IQCODE is a valid instrument for differentiating between normal elderly subjects and patients with subtle cognitive disturbances and for early prediction of the future development of dementia in MCI. We also provide reference values to classify patients at their referral for questionable cognitive decline (although cross validation would be needed before these can be used operationally): an IQCODE score <3.22 makes a diagnosis of MCI unlikely, while values >3.45 indicate patients with MCI with a high risk of transition to frank dementia within the following 2–3 years; intermediate scores point to a diagnosis of MCI with a more unpredictable evolution, deserving longer longitudinal monitoring.

The level of discriminative accuracy obtained by the IQCODE was basically identical to that of the MMSE, and high IQCODE scores also showed the instrument to be a very sensitive and specific marker of progression to dementia. Using ROC curve analysis, the questionnaire even yielded a slightly, though not significantly, higher predictive accuracy than immediate and delayed recall scores, mainly due to the low specificity displayed by both memory measures. Susceptibility of neuropsychological tests to low educational level are unlikely to account for such a finding, given that, in our MCI sample, patients' years of schooling were shown to be unrelated not only to the IQCODE (in agreement with previous evidence suggesting its cultural fairness),27,28,29,30 but also to the RAVLT scores. The most likely explanation is the relatively short duration of study follow up. Evidence has been gathered from both group31 and single32,33 case studies that amnesia may remain isolated for up to 10 years in MCI. An alternative explanation is that memory ability is more affected by physiological aging than performance in everyday activities, but, even though we did find a significant correlation with patient's age for memory tests, we found an even higher correlation for the questionnaire (as described previously27,29 and perhaps reflecting an increasing rate of cognitive decline in older subjects34). The higher proportion of false positives we observed for the RAVLT may then be due to the fact that, unlike informant ratings that directly assess change,29,35,36 recall ability as measured by tests might be confounded by (poor) premorbid intellectual level. The possible contribution of contingent factors interfering with patient performance during the testing session might be a further explanation.

One previous study by Estevez‐Gonzalez et al37 addressed the issue of the validity of the RAVLT in preclinical dementia and also considered the IQCODE. However, their study sample is different; their controls were subjects with subjective memory complaint, rather than elderly from the general population, and non‐converters all had a diagnosis of MCI at follow up and no patient reverted to normality. This may have determined greater overlap among the subgroups, leading to limited predictive validity for the questionnaire.

Another discrepancy with respect to Estevez‐Gonzalez's work deserves comment: correlation between the MMSE and immediate recall at the RAVLT was definitely higher than in our study (and statistically significant). A modest relationship between the two tests is, in fact, puzzling. Restriction of score range might be a possible explanation. In fact, the array of recall scores was much wider in Estevez‐Gonzalez's study, perhaps due to the fact that correlation analysis was performed on the whole study sample (including subjects with subjective memory complaints). The preclinical and conclamate patients with non‐AD dementia included in our study population may have lost points in MMSE items other than those responsible for the relationship with memory tests (verbal registration and recall), whereas Estevez‐Gonzalez et al only enrolled cases of pure amnestic MCI and impending AD.

One further unexpected but intriguing finding of the present study is represented by the worse predictive performance of memory tests after adjustment for age and education, which may perhaps be taken as evidence of the influence exerted by age on the risk of developing dementia (so that scores free of its effect may underestimate risk of conversion).

Non‐AD patients were scarcely represented in our study population, so that we could not expressly evaluate the effects on IQCODE scores of motor disability possibly associated with cerebrovascular disease, or of neuropsychiatric disturbances accompanying frontal dysfunction (although one previous study showed that mood and psychotic disorders per se have limited influence on the IQCODE38). Given the impact these factors have on activities of daily living, they might affect the accuracy of the questionnaire, and may at least partly explain its relatively low specificity in our mixed study sample. In contrast, they did not seem to decrease sensitivity, suggesting that the questionnaire may be valid for a timely detection of different variants of preclinical dementia. This might be because, unlike single neuropsychological tests, caregiver rated scales tap multiple aspects of cognitive and functional competency. The significant correlation we found between the questionnaire and memory scores and correlations with other cognitive domains shown in previous investigations12,29,35 also suggest the composite nature of the general factor underlying the IQCODE.27,28

One possible caveat of the present study design concerns the neuropsychological standards chosen to define the discriminative and predictive power of the IQCODE. The MMSE is unquestionably the mainstay of dementia screening, and episodic verbal memory tests seem to measure up as the strongest predictors of transition from MCI to dementia (see Arnaiz et al3), but both instruments are tuned in to the amnestic, pre‐AD cognitive profile, whereas our MCI sample was rather heterogeneous. Impairment of attention and executive functions, and relative sparing of episodic memory represent the most frequent clinical presentation of vascular and frontotemporal dementia.23,39,40 The MMSE and the RAVLT might thus have been “penalised” by the inclusion of subjects presenting with a non‐AD neuropsychological profile. In truth, had this been the case, we would have expected a major number of false negatives, in particular for memory measures, while recall scores yielded poor specificity, but rather good sensitivity values. Such good sensitivity shown by the two measures indicates that their bias towards AD was limited.

Another limitation of the present data regards their generalisability, given that accuracy values (and cut off points) obtained by the diagnostic instrument under scrutiny depend on the prevalence of the disease in the setting where it is being validated. Our promising findings, however, encourage verification of the accuracy power of the IQCODE in a larger, multicentre clinical sample. Final shortcomings of the present study are the small sample size, the short follow up duration, and the non‐consecutive mode of enrolment. Subjects excluded because they did not have an informant or a sufficiently long follow up appeared to be grossly comparable to those included into the study. However, patients with MCI presenting alone at first referral or lost at follow up might have had milder cognitive and functional impairment; selection bias towards relatively more severe cases may thus not be fully ruled out.

One future interesting adjunct to the present survey might be the assessment of the combined use of the questionnaire with other measures. The correlation we found between the IQCODE and the MMSE was statistically significant, but not very high (similar to findings by Jorm et al29 and Christensen and Jorm30), suggesting that there is actually limited overlap of the information they provide. On the other hand, regression analysis demonstrated that memory measures do not add much to the independent predictive ability of the questionnaire. The combined use of behavioural and non‐cognitive markers of dementing illness (the IQCODE and imaging41 or neurobiological and genetic41,42,43,44 indexes) might perhaps be more promising.17 Finally, systematic investigation of informants' features influencing their rating accuracy (which requires an ad hoc study design) might help in identifying the most reliable collateral sources.

Abbreviations

AD - Alzheimer's disease

AUC - area under the curve

DSM‐IV - Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

FTD - frontotemporal dementia

IQCODE - Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly

MCI - mild cognitive impairment

MMSE - Mini Mental State Examination

NOS - not otherwise specified

RAVLT - Rey's Auditory Verbal Learning Test

ROC - receiver operating characteristic

SVD - subcortical vascular dementia

Footnotes

Competing interests: none

All necessary approval for the study was secured from the ethics committee of St Gerardo Hospital, Monza, and written consent was obtained from patients taking part in the study.

References

- 1.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M.et al Mild cognitive impairment – beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Int Med 2004256240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nestor P J, Scheltens P, Hodges J R. Advances in the early detection of Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 200410(suppl)S34–S41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnaiz E, Almkvist O. Neuropsychological features of mild cognitive impairment and preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neurol Scand 2003107(suppl 179)34–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jorm A F. Methods of screening for dementia: a meta‐analysis of studies comparing informant questionnaire with a brief cognitive test. Alz Dis Associat Dis 199711158–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tierney M C, Szalai J P, Snow W G.et al The prediction of Alzheimer's disease. The role of patient and informant perceptions of cognitive deficits. Arch Neurol 199653423–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daly E, Zaitchik D, Copeland M.et al Predicting conversion to Alzheimer disease using standardized clinical information. Arch Neurol 200057643–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris J C, Storandt M, Miller J P.et al Mild cognitive impairment represents early‐stage Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 200158397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris J C, McKeel D W, Jr, Storandt M.et al Very mild Alzheimer's disease: informant‐based clinical, psychometric and pathologic distinction from normal aging. Neurology 199141469–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnan K R, Levy R M, Wagner H R.et al Informant‐rated cognitive symptoms in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Initial development of an informant‐rated screen (Brief Cognitive Scale) for mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Psychopharmacol Bull 20013579–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tabert M H, Albert S M, Borukhova‐Milov L.et al Functional deficits in patients with mild cognitive impairment: prediction of AD. Neurology 200258758–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visser P J, Verhey F R, Ponds R W.et al Diagnosis of preclinical Alzheimer's disease in a clinical setting. Int Psychogeriatr 200113411–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jorm A F. Assessment of cognitive impairment and dementia using informant reports. Clin Psychol Rev 19961651–75. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorm A F, Korten A E. Assessment of cognitive decline in the elderly by informant interview. Br J Psychiatr 1988152209–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein M F, Folstein S E, McHugh P R. MiniMental State: a practical guide for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiat Res 197612189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Isella V, Villa M L, Frattola L.et al Screening cognitive decline in dementia: preliminary data on the Italian version of the IQCODE. Neurol Sci 200223(suppl 2)S79–S80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rey A. Mémorisation d'une série de 15 mots en 5 répétitions. In: Rey A, ed. L'examen clinique en psychologie. Paris: Presse Universitaire de France, 1958

- 17.Backman L, Jones S, Berger A K.et al Multiple cognitive deficits during the transition to Alzheimer's disease. J Int Med 2004256195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petersen R C, Doody R, Kurz A.et al Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2001581985–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. American Psychiatric Association, ed. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994

- 20.Measso G, Cavarzeran F, Zappalà G.et al The Mini‐Mental State Examination: normative study of an Italian random sample. Dev Neuropsychol 1993977–85. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rockwood K, Wentzel C, Hachinski V.et al Prevalence and outcomes of vascular cognitive impairment. Neurology 200054447–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKahnn G, Drachmann, Folstein M.et al Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: Report of the NINCDS‐ADRDA work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 198434939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neary D, Snowdon J S, Gustafson L.et al Frontotemporal lobar degeneration. A consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 1998511546–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erkinjuntti T, Inzitari D, Pantoni L. Research criteria for subcortical vascular dementia in clinical trials. J Neural Transm Suppl 20005923–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlesimo G A, Caltagirone C, Gainotti G.et al The Mental Deterioration Battery: normative data, diagnostic reliability and qualitative analyses of cognitive impairment. Eur Neurol 199636378–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanley J A, McNeil B J. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology 1983148839–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jorm A F, Jacomb P A. The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): socio‐demographic correlates, reliability, validity and some norms. Psychol Med 1989191015–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuh J L, Teng E L, Lin K N.et al The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) as a screening tool for dementia for a predominantly illiterate Chinese population. Neurology 19954592–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jorm A F, Broe G A, Creasy H.et al Further data on the validity of the informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (IQCODE). Int J Geriatr Psychiatr 199611131–139. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christensen H, Jorm A F. Effect of premorbid intelligence on the Mini‐Mental State and IQCODE. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr 19927159–160. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Backman L, Small B J, Fratiglioni L. Stability of the preclinical episodic memory deficit in Alzheimer's disease. Brain 200112496–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Godbolt A K, Cipolotti L, Anderson V M.et al A decade of pre‐diagnostic assessment in a case of familial Alzheimer's disease: tracking progression from asymptomatic to MCI and dementia. Neurocase 20051156–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stokholm J, Jakobsen O, Czarna J M.et al Years of severe and isolated amnesia can precede the development of dementia in early‐onset Alzheimer's disease. Neurocase 20051148–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson R S, Beckett L A, Barnes L L.et al Individual differences in rates of change in cognitive abilities of older persons. Psychol Aging 200217179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jorm A F, Christensen H, Henderson A S.et al Informant ratings of cognitive decline of elderly people: relationship to longitudinal change on cognitive tests. Age Ageing 199625125–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jorm A F, Scott R, Cullen J S.et al Performance of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) as a screening test for dementia. Psychol Med 199121785–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Estevez‐Gonzalez A, Kulisevsky J, Boltes A.et al Rey verbal learning test is a useful tool for differential diagnosis in the preclinical phase of Alzheimer's disease: comparison with mild cognitive impairment and normal aging. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003181021–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Jonghe J F. Differentiating between demented and psychiatric patients with the Dutch version of the IQCODE. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 199712462–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Brien J T, Erkinjuntti T, Reisberg B.et al Vascular cognitive impairment. Lancet Neurol 2003289–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Mendonca A, Ribeiro F, Guerreiro M.et al Frontotemporal mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 200461–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Visser P J, Verhey F R, Hofman P A.et al Medial temporal lobe atrophy predicts Alzheimer's disease in subjects with minor cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 200272491–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buerger K, Teipel S J, Zinkowski R.et al CSF tau protein phosphorylated at threonine 231 correlates with cognitive decline in MCI subjects. Neurology 200259627–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borroni B, Colciaghi F, Caltagirone C.et al Platelet amyloid precursor protein abnormalities in mild cognitive impairment predict conversion to dementia of Alzheimer type: a 2‐year follow‐up study. Arch Neurol 2003601740–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aggarwal N T, Wilson R S, Beck T.et al The apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele and incident Alzheimer's disease in persons with mild cognitive impairment. Neurocase 2005113–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]