Abstract

Aim

To investigate the feasibility and effect of a home‐based exercise programme on walking endurance, muscle strength, fatigue and function in people with neuromuscular disorders (NMDs).

Methods

20 adults with NMDs recruited to a control (n = 11) or exercise (n = 9) group were assessed by blinded assessors at baseline and at week 8. Walking and strengthening exercises were given to the exercise group in an 8‐week home exercise programme. A 2‐min walk distance was the main outcome measurement; isometric muscle strength, fatigue and function were secondary measurements.

Results

2‐min walk distances were not found to change in either group (p>0.05; control: mean 14.50 (SD 22.06) m; exercise: mean 2.88 (SD 20.08) m), and no difference was observed in the change scores between groups (p>0.05). Leg muscle strength increased in the exercise group (p<0.05) but not in the control group (p>0.05). Significance was reached between the groups with respect to the difference in change in muscle strength scores in the right quadriceps (p<0.05; control: mean −2.82 (SD 4.87) kg; exercise: mean −7.08 (SD 2.82) kg). No change was observed in fatigue or function scores (p<0.05).

Conclusions

A home‐based approach aimed at improving endurance in adults with NMDs is feasible and further investigation on a larger sample is warranted.

People with neuromuscular diseases (NMDs) may lead a relatively sedentary lifestyle, causing secondary detraining.1 Regular exercise leads to health and social benefits even in people with disease.2 The limited clinical research on adults with NMD suggests that they benefit from targeted aerobic and muscle training exercise programmes.3,4 These interventions may be effectively provided in the community setting5,6 and are more effective if supported by a therapist.7

Patients with NMD in the UK receive specialist support from regional centres, which may be located some distance from their home. We developed a training programme that could be delivered with a single demonstration of exercises in the clinic, with follow‐up support delivered through a leaflet and by telephone. We carried out a pilot investigation on the effect of an exercise programme on walking distance, specifically developed for the treatment of a range of NMDs in adults. We also investigated the effect on fatigue, isometric muscle strength and performance, and perceived ability in targeted functional activities.

Method

Participants were adults ⩾16 years old, diagnosed with primary muscle disease and with an abnormal gait pattern attending a regional neuromuscular clinic, or those with a 10 m time exceeding the normal age‐related time by ⩾2 s, but able to walk 10 m without physical help (aids were permitted). People who had physical, cognitive, sensory or psychological impairments, or other conditions precluding full engagement with the experimental paradigm, were excluded. Informed consent was obtained before participation.

On first assessment, the following measurements were obtained:

Sex and age

Anthropometrical data (height (cm), weight (kg) and leg length (cm))

Presenting pathology, medication and medical history

Rivermead Mobility Index (standard 0–15 version)8

Barthel Index (standard 0–100 version)8

Fatigue (Fatigue Severity Scale)9

Self‐reported ability to perform a functional activity (by using a 10 cm Visual Analogue Scale)10,11

Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly12

Maximal isometric muscle strength, best of three attempts (hip flexor–extensor, knee flexor–extensor and ankle flexor–extensor) with a myometer (Lafayette, Indiana, USA).13

10‐m and 2‐min walk times8

The patients in the control group (n = 11, 7 men) had Becker muscular dystrophy (n = 3), myotonic dystrophy (n = 3), polymyositis (n = 1), facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (n = 1), inclusion body myositis (n = 1) and congenital myopathy (n = 1). Patients in the exercise group (n = 9, 4 men) had limb girdle muscular dystrophy (n = 4), facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (n = 2), Becker muscular dystrophy (n = 1) and myotonic dystrophy (n = 1). Ages ranged from 18 to 81 years, with mean age 44 (SD 12) years. At baseline, one participant in each group used a wheelchair for long‐distance mobility, and three in the exercise group and four in the control group used a walking aid.

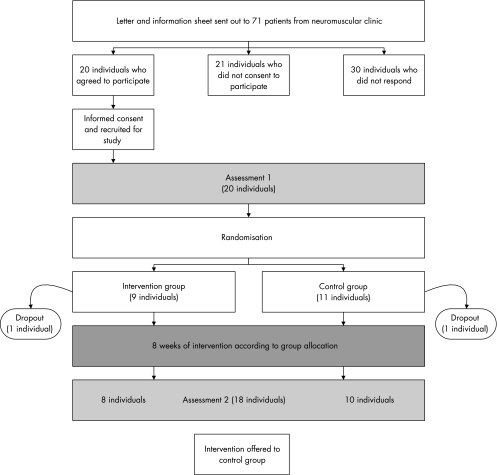

After initial assessment, participants were randomly allocated to the exercise or control group. Randomisation occurred in blocks of four, with consecutively numbered sealed envelopes containing the name of the group derived from computer‐generated random numbers. The control group received standard physiotherapy (advice and support). The training group received an additional exercise intervention for 8 weeks. After 8 weeks, both groups were reassessed (fig 1) by a blinded assessor. At this point, the control group was offered the intervention.

Figure 1 Flow of people through the study.

Intervention

Participants allocated to the exercise programme were introduced to the intervention (walking and strengthening exercises) that was carried out on alternate days. They were familiarised with Borg's CR10 Exercise Symptom Rating Scale by a standard method,14 and were asked to walk for as long as possible up to 20 min at a light subjective exercise intensity, taking breaks if required. When participants completed the 20 min, they were encouraged to increase the walking intensity towards a moderate level by using the CR10 scale.

Participants were given two exercises each for leg muscle endurance and core stability, and were encouraged to gradually increase the number of repetitions, decreasing the number and length of rest breaks until they could perform each exercise for 2.5 min. At this point, they were guided to increase the difficulty of the exercises by increasing the range performed. In sessions where the difficulty was increased, participants were guided to perform as many repetitions as possible and in subsequent sessions to increase this number until they could exercise for 2.5 min. When the full range was achieved, difficulty was increased by performing exercises against resistance, by using gravity, with participants again being guided to perform as many repetitions as possible, and to increase this number in subsequent sessions.

To measure exercise compliance during the intervention period, pedometer counts and self‐reported compliance diaries (exercises and walking) were recorded.15

Participants were given a handout with details of their exercises. On the day after the initial assessment and every week, a researcher contacted the participants by telephone to support them in their exercise progression.

Sample characteristics were summarised with descriptive statistics. Data were examined for initial between‐group differences and for between‐group differences in change scores. Owing to the small sample sizes and rejection of normality assumptions, non‐parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U test and Wilcoxon test) were used, with the significance level set at 5%. Data were analysed with the SPSS V.12.01.

Results

Figure 1 shows the time line and flow of participants recruited to the study. One participant dropped out from each arm of the study for reasons unrelated to the intervention.

Self‐reported compliance by the exercise group rendered a mean walking exercise value of 106% (range 78–160) and an endurance exercise value of 104% (range 67–152). The mean of pedometer counts taken in the intervention period at week 1 was 6098 (SD 1901; range 2798–8331) steps, with no significant increase seen during the weeks after the intervention: mean change −1485 (SD 2681; p>0.05).

At baseline, we observed no difference between groups (table 1). The exercise group improved markedly in all strength measurements. The difference in change in muscle strength scores reached significance between the groups in the right quadriceps (p<0.05; table 1). We observed no effects on walking measurements, disability, mobility or fatigue.

Table 1 Measurements at baseline and at reassessment (mean (SD) range).

| Week 1 Baseline | Change in score, weeks 1–8 Reassessment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Control group | Exercise group | Control group | Exercise group | ||

| Disease duration (years) | 15.3 (17.2) 0.5–52 | 25.6 (18.9) 3–56 | ||||

| Height (cm) | 177.6 (10.9) 191.2–157.5 | 172.5 (8.9) 182.5–163.2 | ||||

| Weight (kg) | 79.1 (13.9) 110–64 | 79.1 (17) 59–103 | ||||

| 10‐m walk (s) | 11.93 (4.85) 5.19–21.18 | 11.03 (3.82) 6.25–18 | 0.43 (2.06) −3.96–4.07 | I | −0.30 (0.91) −2.34–0.40 | D |

| 2‐min walk (m) | 93.67 (29.11) 53–136 | 97.06 (43.62) 48–184.57 | 14.50 (22.06) −8.00–64.00 | D | 2.88 (20.08) −18.00–41.00 | D |

| Strength quadriceps L (kg) | 9.83 (6.25) 3.8–22.4 | 9.3 (4.00) 2.6–15.5 | −2.26 (4.85) −12.00–4.70 | I | −5.08 (3.18) −7.47–1.00 | I†** |

| Strength quadriceps R (kg) | 10.28 (6.69) 3.2–22.4 | 9.1 (3.53) 2.5–14.5 | −2.82 (4.87) −13.40–2.60 | I | −7.08 (2.82) −12.30–3.20 | I†* |

| Strength iliopsoas L (kg) | 11.08 (5.26) 4.5–20.3 | 9.01 (2.63) 3.9–12.5 | −2.20 (4.57) −9.30–6.70 | I | −5.59 (5.58) −14.90–0.02 | I† |

| Strength iliopsoas R (kg) | 12.68 (4.17) 7.2–21 | 9.28 (3.73) 2–14.8 | −2.13 (5.57) −13.30–7.30 | I | −4.20 (5.91) −13.80–3.77 | I† |

| Strength TA L (kg) | 6.85 (4.66) 1.5–14.7 | 4.88 (4.63) 0 11.2 | −1.93 (2.04) −6.60–0.50 | I† | −5.35 (5.20) −13.80–0.10 | I† |

| Strength TA R (kg) | 7.03 (4.88) 1.3–16.8 | 3.65 (3.14) 0–8.4 | −2.07 (5.38) −16.50–3.40 | I | −4.90 (5.92) −13.80–3.95 | I† |

| Rivermead Mobility Index | 12 (2) 9–15 | 11 (2) 9–15 | 0.20 (1.48) −2.00–3.00 | D | −0.88 (1.46) −4.00–0.00 | I |

| Fatigue Severity Scale | 5 (1) 3–6 | 5 (1) 4–5 | 0.08 (0.90) −1.03–1.88 | I | 0.30 (0.74) −0.68–1.63 | I |

| Visual Analogue Scale | 7 (3) 1–10 | 8 (1) 6–9 | 1.96 (1.83) −1.10–4.80 | I | 1.13 (1.73) −0.60–4.20 | I |

| Barthel Index (kg) | 97 (3) 90–100 | 96 (7) 80–100 | −0.50 (4.38) −10.00–5.00 | I | −2.5 (7.56) −20–5 | I |

| PASE | 112 (75) 43–295 | 145 (103) 64–302 | −43.49 (100.74) −237.10–60.74 | I | −11.64 (38.31) −74.02–41.35 | I |

I, improvement; D, deterioration; L, left; PASE, Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly; R, right; TA, Tibialis anterior.

*Mann–Whitney U test, p<0.05.

**Mann–Whitney U test, p<0.1.

†Wilcoxon test, p<0.05.

Values are mean (SD) range, unless specified otherwise.

A power calculation to determine the sample size required us to observe between‐group differences in the measurement of walking distance; taking a power of 0.9, and α of 0.05, SD of 21.07 and difference between groups of 11.62 suggests that a sample size of 70 would be needed.

Discussion

We found that participants tolerated and adhered to the exercise programme. All the muscles of participants in the exercise group increased in strength, with statistical significance over the control group achieved in the right quadriceps. Walking distance and speed did not change markedly in either group, and no change was observed in disability or fatigue. Analysis shows that a sample of 70 would be required to show between‐group differences in walking distance, with smaller numbers to show significant differences in muscle measurements. Our findings are promising, and an adequately powered study investigating the delivery of a home exercise programme from current neuromuscular clinics is indicated.

Our study has certain limitations. The sample size was small. Participants recounted their own compliance and step count to the researchers during the weekly telephone support. Also, we were unable to monitor the control group. Informally reported activity levels increased in the control group, which may have been because we mentioned the possible benefits of exercise while gaining informed consent.

Although our findings are encouraging, other systems for delivering exercises can be investigated. Future studies on a larger sample of participants with a range of conditions and impairment levels should observe the natural time course of the disease on specific strength, community mobility measurements and quality of life before examining the delivery and long‐term follow‐up of an exercise programme and its effect.

Conclusion

Improving endurance and function in adults with NMDs is feasible and well tolerated. Home delivery of such an exercise programme is a novel, practical and easily implemented approach in busy outpatient clinics in the National Health Survey. Further investigation is warranted.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Muscular Dystrophy Campaign and the people who participated in our study. The University and Oxford Research Ethics Committee granted approval.

Abbreviations

NMD - neuromuscular disorder

References

- 1.Kilmer D D. Response to aerobic exercise training in humans with neuromuscular disease. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 200281S148–S150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santiago M, Coyle C. Leisure‐time physical activity and secondary conditions in women with physical disabilities. Disabil Rehabil 200426485–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van der Kooi E L, Lindeman E, Riphagen I. Strength training and aerobic exercise training for muscle disease. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2005 Jan 25;(1): CD003907. Review. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003907 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Olsen D B, Orngreen M C, Vissing J. Aerobic training improves exercise performance in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Neurology 2005641064–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeBolt L S, McCubbin J A. The effects of home‐based resistance exercise on balance, power, and mobility in adults with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 200485290–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan P, Richards L, Wallace D.et al A randomized, controlled pilot study of a home‐based exercise program for individuals with mild and moderate stroke. Stroke 1998292055–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Logan P A, Gladman J R F, Avery A.et al Randomised controlled trial of an occupational therapy intervention to increase outdoor mobility after stroke. BMJ 20043291372–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wade D T.Measurement in neurological rehabilitation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992

- 9.Krupp L B L N, Muir‐Nash J, Steinberg A D. The Fatigue Severity Scale. Arch Neurol 1989461121–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flachenecker P, Kumpfel T, Kallmann B.et al Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a comparison of different rating scales and correlation to clinical parameters. Mult Scler 20028523–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krupp L B, LaRocca N G, Muir‐Nash J.et al The fatigue severity scale. Arch Neurol 1989461121–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Washburn R A, Smith K W, Jette A M.et al The Physical‐Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) – development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol 199346153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilmer D D, McCrory M A, Wright N C.et al Hand‐held dynamometry reliability in persons with neuropathic weakness. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997781364–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noble B, Robertson R.Perceived exertion. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1996

- 15.Cyarto E V, Myers A M, Tudor‐Locke C. Pedometer accuracy in nursing home and community‐dwelling older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 200436205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]