Abstract

Background

The medical care of patients with acute stroke varies considerably between countries. This could lead to measurable differences in mortality and functional outcome.

Objective

To compare case mix, clinical management, and functional outcome in stroke between 11 countries.

Methods

All 1484 patients from 11 countries who were enrolled into the tinzaparin in acute ischaemic stroke trial (TAIST) were included in this substudy. Information collected prospectively on demographics, risk factors, clinical features, measures of service quality (for example, admission to a stroke unit), and outcome were assessed. Outcomes were adjusted for treatment assignment, case mix, and service relative to the British Isles.

Results

Differences in case mix (mostly minor) and clinical service (many of prognostic relevance) were present between the countries. Significant differences in outcome were present between the countries. When assessed by geographical region, death or dependency were lower in North America (odds ratio (OR) adjusted for treatment group only = 0.52 (95% confidence interval, 0.39 to 0.71) and north west Europe (OR = 0.54 (0.37 to 0.78)) relative to the British Isles; similar reductions were found when adjustments were made for 11 case mix variables and five service quality measures. Similarly, case fatality rates were lower in North America (OR = 0.44 (0.30 to 0.66)) and Scandinavia (OR = 0.50 (0.33 to 0.74)) relative to the British Isles, whether crude or adjusted for case mix and service quality.

Conclusions

Both functional outcome and case fatality vary considerably between countries, even when adjusted for prognostic case mix variables and measures of good stroke care. Differing health care systems and the management of patients with acute stroke may contribute to these findings.

Keywords: case mix, country, outcome, service quality, stroke

Outcome and the incidence of stroke vary between different countries.1,2,3 Variations in case mix, including demographics (age, sex), and in the prevalence of vascular risk factors explain some of these differences.4,5,6 Disparities in outcome may also result from variations in medical practice, such as the use of stroke units, which are known to reduce death and disability,7 and the treatment of acute stroke.8 Finally, different processes of care may also be important—for example, hospital admission rates for stroke differ across various countries.9

Within the Western world it might be expected that functional outcome corrected for case mix and service provision would be similar. However, evidence suggests that this may not be the case. In a study comparing outcome in 12 centres (22 hospitals) in seven European countries, outcome varied twofold when adjusted for case mix and the use of health service resources.8 Analysis of functional outcome in the international stroke trial showed similar findings.10 In both studies, outcome was worst in the United Kingdom.8,10 In contrast, functional outcome was not significantly different between countries when corrected for case mix and health care resource use in the GAIN trial, despite significant variations in unadjusted case fatality.11

In this study we compared case mix, clinical management, and functional outcome between 11 countries to assess this question further, using data from the tinzaparin in acute ischaemic stroke trial (TAIST).12

Methods

TAIST

TAIST compared the safety and efficacy of tinzaparin (low molecular weight heparin) given at high dose (175 anti‐Xa IU/kg/day), tinzaparin at medium dose (100 anti‐Xa IU/kg/day), and aspirin (300 mg once daily) in patients with acute ischaemic stroke.12 The principal investigators from the 100 centres participating in TAIST were experienced in taking part in acute stroke trials. All information was collected prospectively as part of the trial protocol.

Case mix/prognostic factors

Case mix variables included demographic factors (age, sex, race); vascular risk factors (smoking, history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, stroke, myocardial infarction); premorbid dependency (modified Rankin Scale (mRS)); stroke syndrome; severity (Scandinavian Neurological Stroke Scale (SSS)); systolic blood pressure; investigations (atrial fibrillation on ECG, visible infarct on computed tomography (CT)); time to randomisation; and pre‐stroke prevention (aspirin, anticoagulation, antihypertensive treatment, lipid lowering treatment).

Clinical management

The use of evidence based interventions in hospital was recorded: admission to an acute stroke unit (ASU) or a stroke rehabilitation unit (SRU), or both; application of venous compression stockings; treatment by a physiotherapist or speech and language therapist, or both; and secondary prevention (aspirin, anticoagulation, antihypertensive treatment, lipid lowering treatment).

Outcome

Outcome was determined as combined death or dependency (mRS >2), measured at day 180 and recorded by face to face interview, length of stay in hospital, and discharge disposition.

Country and geographical region

Outcome was assessed by the 11 participating countries and aggregates of these, defined by geographical region and similarity of health care system: British Isles (Ireland, UK), Franco (Belgium, France); North America (Canada), north‐west Europe (Germany, Netherlands), and Scandinavia (Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden).

Definitions

TAIST used the following definitions for stroke units:

Acute stroke unit (ASU): “high dependency nursing unit (or area) caring only/mainly for patients with acute stroke and providing close monitoring of neurological and vascular signs”12;

Stroke rehabilitation unit (SRU): “dedicated rehabilitation unit (or area) caring only/mainly for patients with recent stroke and providing multidisciplinary therapy (for example, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy)”.12

Statistical analysis

Prognostic case mix factors, clinical management factors, and outcomes were compared by country and geographical region, using χ2 tests in the case of categorical data and Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous data. Models employing logistic regression and Cox proportional hazard approaches were developed using variables known to be of prognostic significance.13 The likelihood test was used for assessing homogeneity. All analyses were carried out using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Significance was taken at p<0.05 and 95% confidence intervals are given.

Results

Subjects

In all, 1499 patients were randomised; however, the emergence of exclusion criteria prevented treatment in 15 patients. Analyses were undertaken on the 1484 patients with acute ischaemic stroke who received at least one randomised treatment with tinzaparin or aspirin.12 The number of patients enrolled by country varied between 27 (Finland) and 388 (Canada) (table 1). There were significant statistical differences in the demographic and clinical characteristics of the enrolled patients (except for sex and the incidence of previous stroke) between the countries (table 1), including premorbid independence (mRS = 0, Denmark 57.3%, France 88.5%), previous hypertension (Norway 32.9%, Belgium 67.5%), atrial fibrillation (Finland 0.0%, Ireland 26.2%), and total anterior circulation infarct (Germany 2.8%, Finland 63.0%). Similarly, the prevalence of pre‐stroke vascular prophylaxis varied between countries (table 2)—for example, lipid lowering treatment (Finland 0.0%, Belgium 22.5%).

Table 1 Baseline demographics, risk factors, and clinical measures, by country.

| Variable | Country | Total | p Value | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | Canada | Denmark | Finland | France | Germany | Ireland | Nether lands | Norway | Sweden | UK | ||||||||||||||||

| No of subjects | 40 | 388 | 110 | 27 | 191 | 36 | 61 | 143 | 82 | 123 | 283 | 1484 | ||||||||||||||

| Centres | 4 | 27 | 6 | 4 | 18 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 15 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| Age (y) | 72.8 (8.8) | 70.8 (11.2) | 72.4 (11.7) | 69.6 (10.6) | 70.1 (12.4) | 70.7 (10.3) | 70.3 (12.1) | 71.8 (10.8) | 75.3 (7.9) | 74.8 (8.1) | 71.1 (11.0) | 71.6 (11.0) | 0.0012 | |||||||||||||

| Sex (male, %) | 22 (55.0) | 218 (56.2) | 58 (52.7) | 16 (59.3) | 113 (59.2) | 19 (52.8) | 33 (54.1) | 67 (46.9) | 48 (58.5) | 68 (55.3) | 145 (51.2) | 807 (54.4) | 0.66 | |||||||||||||

| Race, white (%) | 40 (100) | 356 (91.8) | 110 (100) | 27 (100) | 186 (97.4) | 36 (100) | 61 (100) | 139 (97.2) | 82 (100) | 123 (100) | 269 (95.1) | 1429 (96.3) | 0.0002 | |||||||||||||

| Current smoking (%) | 11 (27.5) | 116 (29.9) | 50 (45.5) | 4 (14.8) | 27 (14.1) | 6 (16.7) | 18 (29.5) | 35 (24.5) | 20 (24.4) | 20 (16.3) | 75 (26.5) | 382 (25.7) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| Previous HT (%) | 27 (67.5) | 225 (58.0) | 38 (34.5) | 14 (51.9) | 100 (52.4) | 22 (61.1) | 33 (54.1) | 68 (47.6) | 27 (32.9) | 54 (43.9) | 119 (42.0) | 727 (49.0) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| Previous DM (%) | 7 (17.5) | 97 (25.0) | 17 (15.5) | 6 (22.2) | 35 (18.3) | 5 (13.9) | 6 (9.8) | 20 (14.0) | 7 (8.5) | 18 (14.6) | 32 (11.3) | 250 (16.8) | 0.0002 | |||||||||||||

| Previous MI (%) | 5 (12.5) | 90 (23.2) | 12 (10.9) | 6 (22.2) | 12 (6.3) | 2 (5.6) | 8 (13.1) | 15 (10.5) | 14 (17.1) | 22 (17.9) | 46 (16.3) | 232 (15.6) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| Previous stroke (%) | 5 (12.5) | 58 (15.9) | 11 (10.0) | 2 (7.4) | 10 (5.2) | 5 (13.9) | 7 (11.5) | 18 (12.6) | 12 (14.6) | 17 (13.8) | 48 (17.0) | 193 (13.0) | 0.06 | |||||||||||||

| Premorbid mRS ( = 0, %) | 24 (60.0) | 295 (76.0) | 63 (57.3) | 22 (81.5) | 169 (88.5) | 26 (72.2) | 39 (63.9) | 104 (72.7) | 55 (67.1) | 76 (61.8) | 179 (63.3) | 1052 (70.9) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| OCSP type (TACI, %) | 25 (62.5) | 97 (25.0) | 21 (19.1) | 17 (63.0) | 65 (34.0) | 1 (2.8) | 34 (55.7) | 66 (46.2) | 25 (30.5) | 52 (42.3) | 119 (42.0) | 522 (35.2) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| SSS | 30.3 (12.8) | 34.8 (12.4) | 36 (11.8) | 31.9 (13.1) | 29.4 (13.7) | 36.1 (11.6) | 28.6 (11.8) | 30.4 (12.3) | 35.5 (10.0) | 32.5 (13.1) | 30.0 (13.1) | 32.3 (12.8) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| SBP (mm Hg) | 152.2 (19.6) | 153.8 (21.9) | 162.8 (24.2) | 154.7 (18.6) | 157.0 (23.5) | 159.2 (19.0) | 155.2 (20.0) | 157.8 (23.7) | 157.2 (19.9) | 163.3 (21.0) | 153.0 (23.0) | 156.2 (22.4) | 0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| AF on ECG (%) | 1 (2.5) | 26 (6.7) | 10 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 18 (9.4) | 3 (8.3) | 16 (26.2) | 16 (11.2) | 8 (9.8) | 31 (25.2) | 52 (18.4) | 181 (12.2) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| Infarct on CT (%) | 14 (35.0) | 230 (59.3) | 76 (69.1) | 21 (77.8) | 91 (47.6) | 26 (72.2) | 38 (62.3) | 78 (54.5) | 41 (50.0) | 81 (65.9) | 201 (71.0) | 897 (60.4) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| Time to randomisation (h) | 24.2 (13.0) | 25.8 (13.1) | 28.6 (12.9) | 28.9 (13.4) | 21.7 (12.9) | 16.1 (9.8) | 31.1 (11.4) | 22.3 (11.9) | 28.7 (11.9) | 24.4 (11.7) | 30.6 (13.6) | 26.1 (13.2) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

Values are mean (SD) or frequency (%); comparison by χ2 test or Kruskal–Wallis test.

AF, atrial fibrillation; CT, computed tomography; DM, diabetes mellitus; HT, hypertension; MI, myocardial infarction; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; OCSP, Oxford Community Stroke Project; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SSS, Scandinavian Stroke Scale (range 0–58); TACI, total anterior circulation infarction.

Table 2 Clinical management before, during, and after acute ischaemic stroke, by country.

| Variable | Country | Total | p Value | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | Canada | Denmark | Finland | France | Germany | Ireland | Netherlands | Norway | Sweden | UK | ||||||||||||||||

| No of subjects | 40 | 388 | 110 | 27 | 191 | 36 | 61 | 143 | 82 | 123 | 283 | 1484 | ||||||||||||||

| Pre‐stroke | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Antiplatelet (%) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (7.4) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 8 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 5 (4.1) | 3 (1.1) | 24 (1.6) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| Anticoagulation (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.3) | 0.28 | |||||||||||||

| Antithrombotic (%) | 2 (5.0) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (1.8) | 2 (7.4) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 8 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 6 (4.9) | 3 (1.1) | 28 (1.9) | 0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| Antihypertensive (%) | 28 (70) | 186 (47.9) | 45 (40.9) | 12 (44.4) | 97 (50.8) | 17 (47.2) | 31 (50.8) | 70 (48.9) | 35 (42.7) | 63 (51.2) | 98 (34.6) | 682 (46.0) | 0.0008 | |||||||||||||

| Lipid lowering (%) | 9 (22.5) | 32 (8.3) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 20 (10.5) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (3.3) | 18 (12.6) | 2 (2.4) | 8 (6.5) | 7 (2.5) | 100 (6.7) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| In hospital | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ASU (%) | 5 (12.5) | 60 (15.5) | 42 (38.2) | 4 (14.8) | 45 (23.6) | 13 (36.1) | 1 (1.6) | 68 (47.8) | 53 (64.6) | 56 (45.5) | 225 (79.5) | 572 (38.5) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| SRU (%) | 16 (40.0) | 84 (21.6) | 63 (57.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | 24 (66.7) | 3 (4.9) | 96 (67.1) | 32 (39.0) | 55 (44.7) | 80 (28.3) | 454 (30.6) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| Stroke unit (%) | 17 (42.5) | 141 (36.3) | 90 (81.8) | 4 (14.8) | 45 (23.6) | 29 (80.6) | 4 (6.6) | 113 (79.0) | 82 (100) | 96 (78.0) | 234 (82.7) | 855 (57.6) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| Compression stockings (%) | 35 (87.5) | 149 (38.4) | 15 (13.6) | 6 (22.2) | 118 (61.8) | 29 (80.6) | 41 (67.2) | 135 (94.4) | 13 (15.9) | 16 (13.0) | 246 (86.9) | 803 (54.1) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| Physiotherapy (%) | 34 (85.0) | 326 (84.0) | 98 (89.1) | 23 (85.2) | 168 (88.0) | 34 (94.4) | 52 (85.2) | 127 (88.8) | 78 (95.1) | 102 (82.9) | 249 (88.0) | 1291 (87.0) | 0.0009 | |||||||||||||

| Speech therapy (%) | 17 (42.5) | 171 (44.1) | 28 (25.5) | 9 (33.3) | 32 (16.8) | 19 (52.8) | 38 (62.3) | 50 (35.0) | 18 (22.0) | 17 (13.8) | 138 (48.8) | 537 (36.2) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| Post‐stroke | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Antiplatelet* (%) | 16 (57.1) | 207 (64.7) | 70 (76.1) | 19 (76.0) | 91 (64.5) | 20 (80.0) | 22 (73.3) | 89 (78.8) | 56 (84.9) | 67 (84.8) | 141 (77.5) | 798 (72.5) | 0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| Anticoagulation† (%) | 3 (25.0) | 23 (35.4) | 3 (20.0) | 2 (100.0) | 4 (8.2) | 2 (18.2) | 9 (29.0) | 1 (3.6) | 7 (53.9) | 7 (15.9) | 22 (22.5) | 83 (22.6) | 0.0002 | |||||||||||||

| Antithrombotic (%) | 19 (47.5) | 230 (59.7) | 73 (68.2) | 21 (77.8) | 95 (50.0) | 22 (61.1) | 31 (50.8) | 90 (63.8) | 63 (79.8) | 74 (60.2) | 163 (58.2) | 881 (60.0) | 0.0002 | |||||||||||||

| Antihypertensive (%) | 22 (55.0) | 216 (55.7) | 46 (41.8) | 11 (40.7) | 97 (50.8) | 21 (58.3) | 24 (39.3) | 53 (37.1) | 39 (47.6) | 66 (53.7) | 108 (38.2) | 703 (47.4) | 0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| Lipid lowering (%) | 8 (20.0) | 63 (16.2) | 4 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 25 (13.1) | 1 (2.8) | 10 (16.4) | 22 (15.4) | 5 (6.1) | 15 (12.2) | 34 (12.0) | 187 (12.6) | 0.0028 | |||||||||||||

Values are n (%); comparison by χ2 test or Kruskal–Wallis test.

*Per cent anticoagulation: number on anticoagulant/number with presumed cardioembolic ischaemic stroke.

†Per cent antiplatelet: number on antiplatelet/number with presumed non‐cardioembolic ischaemic stroke.

ASU, acute stroke unit; SRU, stroke rehabilitation unit.

Clinical practice

In‐hospital care varied considerably between countries, including (table 2): admission to an SRU (Finland 0.0%, Netherlands 67.1%), use of venous compression stockings (Sweden 13.0%, Netherlands 94.4%), and management by a speech and language therapist (Sweden 13.8%, Ireland 62.3%). Similarly, secondary prevention rates differed significantly between countries (table 2): anticoagulation in patients with presumed cardioembolic stroke (Netherlands 3.6%, Finland 100.0%), and antiplatelet treatment in non‐cardioembolic stroke (Belgium 57.1%, Norway 84.9%).

Functional outcome

The 11 countries differed in each measure of outcome (table 3), including combined death and dependency at day 180 (mRS >2: Germany 44.4%, Ireland 67.2%), length of stay in hospital (Denmark/Finland 11 days, Ireland 39 days), and discharge to an institution.

Table 3 Outcome measured as death, death or dependency (mRS>2), length of stay in hospital, and institutionalisation, by country.

| Variable | Country | Total | p Value | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | Canada | Denmark | Finland | France | Germany | Ireland | Netherlands | Norway | Sweden | UK | ||||||||||||||||

| Subjects | 40 | 388 | 110 | 27 | 191 | 36 | 61 | 143 | 82 | 123 | 283 | 1484 | ||||||||||||||

| Dead | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Day 10 | 1 (2.5) | 7 (1.8) | 2 (1.8) | 1 (3.7) | 9 (4.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.3) | 11 (7.7) | 3 (3.7) | 8 (6.5) | 19 (6.7) | 63 (4.2) | 0.035 | |||||||||||||

| Day 180 (%) | 6 (15.0) | 38 (9.8) | 12 (10.9) | 1 (3.7) | 32 (16.8) | 0 (0) | 13 (21.3) | 31 (21.7) | 8 (9.8) | 16 (13.0) | 58 (20.5) | 215 (14.5) | 0.0002 | |||||||||||||

| mRS>2 Day 180 (%) | 23 (57.5) | 185 (47.7) | 55 (50.0) | 16 (59.3) | 119 (62.3) | 16 (44.4) | 41 (67.2) | 73 (51.0) | 46 (56.1) | 77 (62.6) | 179 (63.3) | 830 (55.9) | 0.0040 | |||||||||||||

| Length of stay (d) | 23 (14 to 47) | 14 (8 to 27) | 11 (8 to 25) | 11 (9 to 17) | 16 (12 to 22) | 21 (15 to 39) | 39 (16 to 78) | 19 (12 to 35) | 14 (10 to 20) | 17 (10 to 35) | 27 (10 to 79) | 16 (10 to 34) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

| Institution (%) | 18 (47.4) | 212 (56.4) | 62 (57.9) | 21 (80.8) | 125 (69.4) | 23 (63.9) | 30 (51.7) | 66 (52.0) | 55 (69.6) | 60 (52.6) | 97 (37.0) | 769 (54.8) | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||

Values are number (%) or median (interquartile range); comparison by χ2 test or Kruskal–Wallis test.

mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

The following case mix variables were associated with a poor outcome in univariate analyses: increasing age, female sex, premorbid disability (mRS 1,2), non‐smoker, history of previous stroke, diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, increasing stroke severity (SSS), and visible infarction on the baseline CT (data not shown). Measures of clinical care were also associated with a poor outcome: non‐admission to an SRU, care by a physiotherapist or speech therapist or both, and the use of compression stockings. Functional outcome was not related to race, time to treatment, admission to an ASU, or treatment with tinzaparin versus aspirin (data not shown). When assessing the effect of treatment on functional outcome by country, comparisons of tinzaparin versus aspirin did not differ, except in the case of German patients in whom tinzaparin was inferior to aspirin.

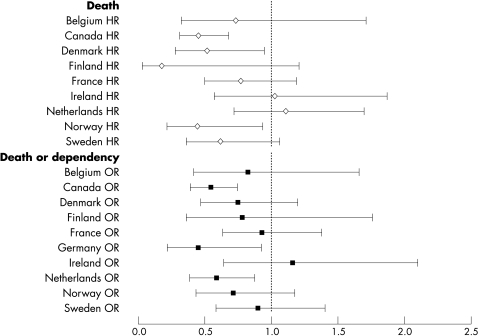

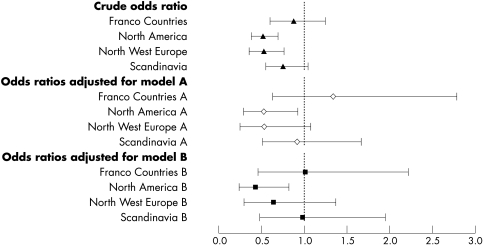

The odds of being dead or dependent (mRS >2) at six months were significantly lower in Canada, Germany, and the Netherlands compared with the UK (fig 1). When analysed by geographical region, death or dependency was 50% lower in North America and north west Europe compared with the British Isles (p<0.0001) (fig 2). The significant difference in outcome between North America and the British Isles remained following adjustment for case mix variables alone (model A), and case mix with indicators of clinical care (model B) (fig 2).

Figure 1 Hazard ratio (HR) of death, and odds ratio (OR) of a poor functional outcome (dead or dependent, modified Rankin Score 3–6), with 95% confidence intervals, at 180 days by country, relative to the United Kingdom (adjusted for treatment group, tinzaparin, aspirin).

Figure 2 Odds ratios (with 95% confidence intervals) of a poor outcome (dead or dependent, modified Rankin Score 3–6) at day 180 by geographical region, relative to the British Isles. Crude and adjusted rates are given. All models include adjustment for TAIST treatment group. Model A, case mix: age, sex, race, current smoking, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke, systolic blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, severity (SSS), infarct on baseline CT, prior modified Rankin Scale, time to treatment. Model B, case mix and clinical care: model A, plus care in an acute stroke unit, care in a stroke rehabilitation unit, physiotherapy, speech therapy, stockings. CT, computed tomography; SSS, Scandinavian Neurological Stroke Scale; TAIST, tinzaparin in acute ischaemic stroke trial.

Death

The 11 countries differed in death rates by day 10 (end of treatment) and day 180 (Germany 0.0%, Netherlands 21.7%). The following case mix variables were associated with an increased risk of death in univariate analyses: increasing age, premorbid disability, non‐smoking, atrial fibrillation, previous stroke, diabetes mellitus, increasing stroke severity, and visible infarction on CT. Measures of care were also associated with case fatality: use of compression stockings, lack of physiotherapy (all p<0.05, data not shown). Sex, race, blood pressure, admission to an ASU or SRU, speech therapy, and treatment with tinzaparin were not related to death. When assessing the effect of treatment on death by country no statistically significant effects were seen (data not shown).

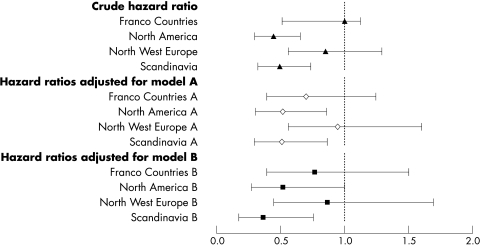

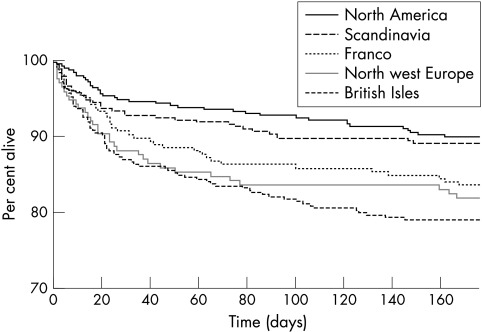

The hazard of death at six months differed significantly by country (p<0.0001); in comparison with the United Kingdom, death rates were lower in Canada, Denmark, Germany, and Norway (fig 1). When grouped by geographical region, death rates were 40–50% lower in North America and Scandinavia than in the British Isles (p = 0.0001) (figs 3 and 4). The significant difference in case fatality remained after adjustment for case mix variables alone, and with service indicators (p<0.0001).

Figure 3 Hazard ratio (with 95% confidence intervals) of death at six months by geographical region, relative to the British Isles. Crude and adjusted rates given. All models include adjustment for TAIST treatment group. Model A, case mix: age, sex, race, current smoking, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke, systolic blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, severity (SSS), infarct on baseline CT, prior modified Rankin Scale, time to treatment. Model B, case mix and clinical care: model A, plus care in an acute stroke unit, care in a stroke rehabilitation unit, physiotherapy, speech therapy, stockings. CT, computed tomography; SSS, Scandinavian Neurological Stroke Scale; TAIST, tinzaparin in acute ischaemic stroke trial.

Figure 4 Kaplan–Meier survival plot for the five geographical regions.

Discussion

The important finding in this study is that functional outcome and death after stroke differed significantly between the 11 countries, and between geographical aggregates of these countries. In univariate analyses, both functional outcome and case fatality varied by a factor of 2, a magnitude that is more powerful than treatment effects associated with stroke units and thrombolysis.7,14 Differences between countries have been observed in previous studies for both functional outcome8,10 and case fatality2,8,10,11 after stroke.

As case mix is well known to influence clinical outcome, variations in outcome will, at least in part, reflect differences in case mix.15 Hence, studies comparing populations need to adjust for case mix,16,17 although this is not without methodological problems and demands rigorous analysis.15 In TAIST, differences in most baseline variables were present, with some likely to be of significant clinical relevance—for example, premorbid status, previous hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and clinical stroke syndrome. Nevertheless, adjustment for up to 13 prognostic factors did not remove differences in outcome between the countries. Similar adjustment for case mix, but using fewer prognostic variables, did not remove outcome differences in other studies.8,10

It is now realised that adjustment for prognostic clinical factors alone is insufficient; process of care (equating to quality of care) also needs to be included, as these factors can have powerful effects on outcome.18,19 We included some of these measures, such as admission to a stroke unit, care by therapists, and the use of compression stockings. Again, adjustment for both case mix and these clinical process measures did not explain the differences in outcome seen in TAIST, a finding that was also seen in BIOMED and IST, although based on fewer variables.8,10

Explaining the residual differences between the countries after adjustment for case mix and process of care is difficult. The TAIST investigators were, in general, experienced in managing stroke and taking part in acute stroke trials, and cared for patients within the context of a stroke service. Furthermore, all patients had CT before enrolment. Several possible explanations exist, relating to chance, systematic bias, and confounding, as for any observational study that does not include consecutively admitted patients.

First, the study was relatively large, and the differences profound and consistent both within (internal validity) and outside the study (external validity),2,8,10 so chance alone is unlikely. It is possible that the care received by patients in a clinical trial is different from routine stroke management. It is also possible that some centres may not be representative of their countries. However, in analysing outcome by geographical regions with similar health services, statistical power was increased thereby reducing the chance that unrepresentative centres may have affected the results.11 We did not analyse outcome by centre as most recruited few patients, thereby limiting the power of analyses.

Second, the interpretation of definitions for case mix variables, quality markers, and outcome might vary between countries, leading to systematic bias. Our data came from an industry sponsored trial with a detailed protocol, and it is unlikely that interpretations in the definitions of clinical variables would differ significantly. There is some evidence that the interpretation of functional status may vary between countries.20,21,22 If relevant, a systematic bias in the recording of both premorbid and post‐stroke mRS would be present and their relation would be very strong, which was not the case in TAIST. Even if a bias in functional outcome was present, the between‐country differences in case fatality, which were of comparable magnitude to those seen for functional outcome, cannot be explained in this manner.

Third, unmeasured variation in case mix or processes of care, or both, may explain the observed differences.23 IST, GAIN, and BIOMED each reported limited numbers of case mix variables,8,10,24 in contrast to our study which adjusted for premorbid function, co‐morbid conditions, clinical process, and brain imaging. However, the inclusion of these factors in the prognostic models was not helpful in explaining between‐country differences in outcome. While other case mix variables might explain some of the observed differences in outcome, it is unlikely that they would exert such a powerful effect individually.

Finally, the differences seen in this study may relate to the quality of hyperacute and acute care—that is, management within 48 hours post‐stroke. Patients who are monitored for, and maintain, physiological homeostasis (for example, blood pressure, temperature, glucose) following acute stroke have an improved outcome.25,26 Some acute stroke patients may also benefit from interventions such as thrombolysis or neurosurgery,27 although these treatments were not given in TAIST. Health care models focusing on the hyperacute phase are variably present within countries but are less common in the British Isles than in North America and much of western Europe. For example, interventions to alter abnormal physiological variables occur less frequently in the United Kingdom.8 Nevertheless, this explanation for the differences in outcome seen in TAIST are largely hypothetical, and randomised controlled trials examining the roles of intensive monitoring and physiological intervention are required.28 Further evidence could also be obtained from observational studies on consecutively admitted patients with data on basic physiological interventions in the acute phase.

In summary, we have shown that outcome from stroke varies significantly between countries, using prospective data from a large multicentre international acute stroke trial. Correction for case mix and markers of service provision did not explain these differences.

Acknowledgements

We thank Leo Pharma A/S for sharing the TAIST database. The analyses and their interpretation were undertaken independently of Leo Pharma A/S. LJG and NS are supported, in part, by the Stroke Association (UK) and BUPA Foundation (UK). PB is Stroke Association Professor of Stroke Medicine. This study was presented, in part, at the 10th European Stroke Conference, Lisbon, 2001.[29]

Abbreviations

ASU - acute stroke unit

BIOMED - European study of stroke care

GAIN - glycine antagonist (GV 150526) in acute stroke

IST - international stroke trial

mRS - modified Rankin Scale

SSS - Scandinavian Neurological Stroke Scale

SRU - stroke rehabilitation unit

TAIST - tinzaparin in acute ischaemic stroke trial

Footnotes

Competing interests: There are no completing interests for any of the authors in terms of the analysis presented here, but all authors apart from LJG and NS were involved in the original TAIST trial. PMWB, PS, GB, PDD, PF, DL, RM, JEO, DO, BR, JJVDS, and AGGT were on the trial steering committee for TAIST, and EL works for Leo Pharma A/S.

References

- 1.Aho K, Harmsen S, Marrquardsen J. Cerebrovascular disease in the community: results of a WHO collaborative study. Bull WHO 19805811–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorvaldsen P, Asplund K, Kuulasmaa K.et al Stroke incidence, case fatality and mortality in the WHO MONICA project. World Health Organisation Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease. Stroke 199526361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feigin V L, Lawes C M, Bennett D A.et al Stroke epidemiology: a review of population‐based studies of incidence, prevalence, and case‐fatality in the late 20th century. Lancet Neurol 2003243–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Carlo A, Lamassa M, Baldereschi M.et al Sex differences in the clinical presentation, resource use, and 3‐month outcome of acute stroke in Europe: data from a multicenter multinational hospital‐based registry. Stroke 2003341114–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamassa M, Di Carlo A, Pracucci G.et al Characteristics, outcome, and care of stroke associated with atrial fibrillation in Europe: data from a multicenter multinational hospital‐based registry (The European Community Stroke Project). Stroke 200132392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Carlo A, Lamassa M, Pracucci G.et al Stroke in the very old: clinical presentation and determinants of 3‐month functional outcome: a European perspective. Stroke 1999302313–2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stroke Unit Trialists' Collaboration Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Library, issue 3. Oxford: Update Software (John Wiley and Sons), 2004

- 8.Wolfe C D, Tilling K, Beech R.et al Variations in case fatality and dependency from stroke in western and central Europe. The European BIOMED Study of Stroke Care Group. Stroke 199930350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brainin M, Bornstein N, Boysen G.et al Acute neurological stroke care in Europe: results of the European Stroke Care Inventory. Eur J Neurol 200075–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weir N U, Sandercock P A, Lewis S C.et al Variations between countries in outcome after stroke in the International Stroke Trial (IST). Stroke 2001321370–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asplund K, Ashburner S, Cargill K.et al Health care resource use and stroke outcome. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 200319267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bath P, Lindenstrom E, Boysen G.et al Tinzaparin in acute ischaemic stroke (TAIST): a randomised aspirin‐controlled trial. Lancet 2001358702–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hankey G J. Long‐term outcome after ischaemic stroke/transient ischaemic attack. Cerebrovasc Dis 200316(suppl 1)14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wardlaw J M, del Zoppo G, Yamaguchi T. Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Library. Oxford: Update Software (John Wiley and Sons), 2002

- 15.Davenport R J, Dennis M S, Warlow C P. Effect of correcting outcome data for case mix: an example from stroke medicine. BMJ 19963121503–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orchard C. Comparing healthcare outcomes. BMJ 19943081493–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halm E A, Chassin M R. Why do hospital death rates vary? N Engl J Med 2001345692–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collaboration SUTs Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care after stoke (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Library. Oxford: Update Software (John Wiley and Sons), 2003

- 19.Asplund K, Hulter‐Ashberg K, Norrving B.et al Riks‐Stroke – a Swedish national quality register for stroke care. Cerebrovasc Dis 200315(suppl 1)5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chamie M. Survey design strategies for the study of disability. World Health Stat Q 198942122–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suris J C, Blum R W. Disability rates among adolescents: an international comparison. J Adolesc Health 199314548–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groce N E. Disability in cross‐cultural perspective: rethinking disability. Lancet 1999354756–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKevitt C, Beech R, Pound P.et al Putting stroke outcomes into context: assessment of variations in the processes of care. Eur J Public Health 200010120–126. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lees K, Lavelle J F, Cunha L.et al Glycine antagonist (GV 150526) in acute stroke: a multicentre, double‐blind placebo controlled phase II trial. Cerebrovasc Dis 20011120–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langhorne P, Tong B, Stott D J. Association between physiological homeostasis and early recovery after stroke. Stroke 2000312526–2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sulter G, Elting J W, Langedijk M.et al Admitting acute ischaemic stroke patients to a stroke care monitoring unit versus a conventional stroke unit: a randomised pilot study. Stroke 200334101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wardlaw J M, del Zoppo G, Yamaguchi T. Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Library. Oxford: Update Software (John Wiley and Sons), 2001

- 28.Langhorne P, Dennis M. Stroke units: the next 10 years. Lancet 2004363834–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bath P, Soerensen P, Lindenstrom E. Outcome after stroke varies between countries: data from the “Tinzaparin in Acute Ischaemic Stroke Trial” (TAIST) [abstract]. Cerebrovasc Dis 200111 (suppl 47) [Google Scholar]