Abstract

This paper documents the bifurcation of the market for commercial marijuana from the market for designer marijuana in New York City. Commercial marijuana is usually grown outdoors, imported to NYC, and of average quality. By contrast, several strains of designer marijuana are usually grown indoors from specially-bred strains and carefully handled for maximum quality. The mechanisms for selling include street/park sellers, delivery services, private sales, and storefronts. Retail sales units vary from $5 to $50 and more, but the actual weights and price per gram of retail marijuana purchases lacks scientific precision. Ethnographic staff recruited marijuana purchasers who used digital scales to weigh a purposive sample of 99 marijuana purchases. Results indicate clear differences in price per gram between the purchases of commercial (avg. $8.20/gram) and designer (avg. $18.02/gram) marijuana. Designer purchases are more likely to be made by whites, downtown (Lower East Side/Union Square area), via delivery services, and in units of $10 bags, $50 cubes, and eighth and quarter ounces. Commercial marijuana purchases are more likely to be made by blacks, uptown (Harlem), via street dealers, and in units of $5 and $20 bags. Imported commercial types Arizona and Chocolate were only found uptown, while designer brand names describing actual strains like Sour Diesel and White Widow were only found downtown. Findings indicate clear divisions between commercial and designer marijuana markets in New York City. The extent that these differences may be based upon different THC potencies is a matter for future research.

Keywords: Marijuana, Markets, Purchases, Sales Units, Weights, Price per gram, Behavioral, Economic, Argot, Consumers, Illicit Sellers, Quantity, Quality, Subculture

1. Introduction

Illicit drug markets have been an interest of social scientists and policy makers for over three decades (Adler, 1985; Agar, 1973; Andrade, Sifaneck, & Neaigus, 1999; Johnson, Goldstein, Schmeider, Lipton, & Spunt, 1985; Johnson, Golub, & Dunlap, 2006; Knutsson, 2000; Kornblum, 1988; Parker, 2000; Preble & Casey, 1969; Single & Kandel, 1977; Williams, 1989, 1992). Less attention, albeit significant, has been paid to marijuana markets in particular (Auld, 1981; Becker, 1953, 1963; Bonnie & H., 1974; Castro, 1995; Curtis & Wendel, 2000; Hamilton, 2005; Jansen, 1989, 1994; Johnson, 1973; Korf, 2002; Rhodes & Sheiman, 1994; Schensul, Huebner, Singer, Feliciano, & Broomhall, 2000; Sifaneck & Kaplan, 1995; Van Vliet, 1990; Wilkins & Casswell, 2003). Although prohibited since 1937 and classified as criminal behavior, the retail sale of marijuana from one person to another is a very common illegal behavior in American society, and its sale constitutes a multi-billion dollar industry (Kleiman, 1989; Office of National Drug Policy, 2004)

A number of frameworks have been developed to help understand the dynamics of illegal retail drug markets. The behavioral paradigm seeks to understand how illicit markets work, emphasizing the social organization and mechanisms by which marijuana is sold and purchased. The economic paradigm focuses primarily upon pricing and values of products. An important review of available studies concluded that neither approach was based upon reliable and detailed data about “how much” consumers used/purchased, nor upon the actual prices paid (Johnson & Golub, 2006; National Research Council (NRC), 2001).

During the past four years, the authors have conducted extensive ethnographic research that documents how a subculture of blunts (marijuana smoked in a cigar shell) has become differentiated from the more traditional marijuana-using “joints subculture” (Dunlap, Johnson, & Sifaneck, 2005; Golub, Johnson, & Dunlap, 2006; Ream, Johnson, Sifaneck, & Dunlap, 2006; Sifaneck, Johnson, & Dunlap, 2005). During the course of this research, research subjects and numerous other marijuana consumers have been observed purchasing marijuana. We noticed that more affluent purchasers reported buying a premium quality product, which we call “designer” marijuana, while the less affluent bought marijuana that regular users perceive to be of lower quality and potency, referred to here as “commercial” marijuana. We noticed several qualitative differences between commercial and designer marijuana not just with respect to who was buying the products but in their origins, language used to talk about them, where they were being purchased, and characteristics of the product itself such as moistness, presence or absence of seeds, etc. that regular users believe hint at potency and the character of the high.

This compelled us to systematically investigate this question: Is the market for designer marijuana systematically different than for commercial marijuana? If so, what are the salient features of these two markets? This article provides some initial research that more systematically documents the organization of marijuana markets in New York City. We will: A) delineate the two marijuana markets encountered, B) explain the mechanisms by which marijuana is typically sold/purchased, and C) provide findings from a preliminary study where retail marijuana purchasers (N=99) carefully weighed their product and price per gram was computed.

1.1 Bifurcated Marijuana Markets Commercial and Designer Varieties

It has long been conventional wisdom among marijuana users that marijuana varies greatly in quality, potency, and character of the high experienced from using it, and that these differences can be attributed to the specific strain of marijuana and the care taken in growing it. “Commercial” grade marijuana describes marijuana that is usually imported from Mexico, Columbia, and Jamaica, although some has been grown in outdoor locations in the USA. It has been grown outdoors, roughly manicured, and has usually been prepared for transport and smuggling by having it compressed into “bricks.” In New York City, sellers and consumers often refer to such marijuana as “Chocolate” from Jamaica or “Arizona” from Northern Mexico, it is also called “mids” and “lows” (and many other terms) by consumers (Johnson, Bardhi, Sifaneck, & Dunlap, 2006).

Distinct from this commercial marijuana is high-quality, deliberately bred, carefully handled, and allegedly more potent designer marijuana. Also called “new marijuana” to reflect its new popularity (Schensul, Huebner, Singer, Feliciano, & Broomhall, 2000), the marijuana itself cannot be fairly called new because high quality breeds and strains of cannabis sativa and cannabis indica have been available to consumers in limited ways for over twenty years. Attractive photographs of various strains of designer marijuana are featured in marijuana enthusiasts’ magazines like High Times and Cannabis Culture, coffee-table photo books like the Cannabible (King, 2001), and on numerous websites offering seeds and cannabis related products for sale. The term “designer” is also appropriate because growers and seed breeders design these varieties by taking different strains of cannabis plants (sometimes in form of seeds, more often in “clones” or plant clippings), combining them, and growing the plants under highly controlled conditions (often hydroponically) indoors. This is similar to the wine industry’s practice of combining different types of grapes to create blends like 40% Merlot/60% Shiraz. Designer varieties have designer labels like Haze, Jack Herer, Sour Diesel, White Widow, Northern Lights, Trainwreck, and many others that users in the know recognize through either personal experience or from reading the publications mentioned earlier. A spectrum of designer strains is consistently available in New York City, and many more, some unheard of to local designer consumers, are available in California, Canada, the Netherlands, and other national and international locations.

Designer marijuana is a status symbol within marijuana subcultures similarly to how designer clothing is a status symbol. According to our observations, the status is a rank that has its privileges, including the privilege of not getting caught as easily: designer marijuana is usually sold via delivery services and private sales rather than on the street. Discreet sales plus indoor production methods provide a very low profile to law enforcement. Understanding this requires a more thorough review

1.2 Mechanisms for Marijuana Sale/Purchase

Curtis and Wendel (2000) describe the retail markets for marijuana on the Lower East Side, differentiating between three modes of retail sale: street-level, indoor sales, and delivery services, while including storefronts as indoor sales. They also indicate the relationships among distributors as freelance, bonded businesses, and corporations. Another important drug market typology (Eck & Gersh, 2000) is the distinction between a “concentrated” versus a “cottage” industry. According to our ethnographic observations, most marijuana selling operations fall far more often in the category of freelance (as is the case with most private dealers) or bonded business (as is the case with many delivery services and storefronts.) Fewer observed marijuana selling operations approached the structure and complexity of a corporate model. In terms of Eck and Gersh’s (2000) framework the markets for marijuana are organized more as a cottage industry with multitudes of different sellers and suppliers, a contention reinforced by our observations in New York City. Research also exists about marijuana when sold within a quasi-legal system of distribution as with the case of “coffeeshops” in the Netherlands (Jansen, 1989; Korf, 2002; Van Vliet, 1990). Recent research of marijuana market behavior based on analysis of the household survey data (Caulkins & Pacula, 2005) reached a number of conclusions; most of these will be confirmed in the analysis of the data below including: few (13%) marijuana sales take place outdoors; many sellers are both users and sellers; the price per gram of marijuana may be affected by a multitude of variables including the relationship of the buyer and seller.

The following typology of the retail marijuana markets in New York City is based upon systematic observations over a number of research projects and years. The first author of this article conducted his dissertation research where he encountered and interviewed 75 sellers of cannabis in New York City in the early 1990s. The present research helped further develop the working typology, and provided support for the actual data collection of the retail measurements during a 5-year National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) funded study entitled “Marijuana/Blunts: Use, Subcultures and Markets” (Eloise Dunlap, PI). In the past thirty years since marijuana has been decriminalized in New York State, a diverse and intricate network of retail urban markets has developed in New York City. Street and park sellers, storefronts, delivery services and private sales represent a working typology of the many ways in which marijuana is bought and sold in New York City. The following section provides a descriptive background of these different modes of retail sale.

Street and Park Markets

Numerous neighborhood locations exist throughout New York City’s five boroughs where marijuana can be purchased fairly easily and on a consistent basis. These dealing “spots” are often separate from street markets for cocaine/crack and heroin. Many of these street-based retail drug spots have operated in the same locations for many years; the sellers and buyers often change, but many of the locations remain the same over periods of time. Increased police enforcement is occasionally effective in shutting down a location for a number of years. One illustrative example of this is in a public park in Lower Manhattan. An active marijuana market has existed there since the late 1960s. This market was effectively shut down for about six years during the height of the Quality of Life Enforcement campaign (Johnson, Golub, Dunlap, Sifaneck, & McCabe, 2006). During these years, persons caught buying, selling or using in the park were arrested and forced to go through “the system.” Police installed video surveillance monitors on one park’s periphery, and stationed a mobile precinct in and trailer located on the edge of the park, making it very discouraging for marijuana sellers or buyers. Over the past four years, as enforcement efforts waned inside and around the park, the marijuana market has returned inside and around the park’s periphery.

Private Sales

Users of marijuana usually know someone who sells the drug, who in turn has connections with someone selling larger quantities, and so on. Essentially many marijuana sales are private sales occurring between people who already know each other (Caulkins & Pacula, 2005). At the lower level, the transactions are informal and involve a fairly low profit margin. They are made behind closed doors in homes, vehicles, and workplaces. Regular and heavy users of marijuana may become involved in distribution networks because marijuana prices are relatively costly and difficult for many users to afford. Informal sellers and larger scale distributors of both designer and commercial marijuana are differentiated on one level by the amounts that they sell and the profit margins that are involved in their sales. Wood (1988) makes a distinction between “sellers” and “dealers” based on the dollar amounts involved in similar private sales. In New York City, however, we did not observe this distinction to be clear-cut. Profit margins exist at each level of distribution, and the cumulative effect for the final “retail” consumer is commonly an inflated price. The following field note summary provides an example:

Bill buys a “Q-P” or a 1/4 of a pound of marijuana (equivalent to 4 ounces or 112 grams) from Dave for 500 dollars. The marijuana is a middle grade sinsemilla from Mexico. Bill does not pay Dave and receives the 4 ounces “fronted,” i.e. on credit. Bill first splits the four ounce bag into individual ounce bags. He then sells two ounces to Lisa, for $175 an ounce, a total of $350. Lisa is buying one ounce for herself, and the other one for her brother-in-law, “an older yuppie with no more connections.” Bill sells the third ounce to George, a friend he made in college, for $175, the same per ounce price he charged Lisa, but since George is better friend, which figures into this equation, will be charged the same bulk rate as Lisa. At this point, Bill has “moved” or sold 3 of the 4 ounces paying off the whole quarter pound, leaving a $25 profit. Bill’s friend Bob calls asking “if you could break me off a piece of that ounce.” Bill sells Bob a quarter of an ounce for $45. Bill’s final profit is $70 and 3/4 of an ounce (21 grams) of marijuana. Bill is a “regular smoker… pretty much everyday, but not necessarily everyday” smoker. The 3/4 of an ounce will last him approximately 2–3 weeks. Bill comments on his role as a casual seller: “My friends are happy since the prices I offer them are the best around, I don’t have to pay for the weed I smoke, and maybe I get a little extra money for the weekend.”

Because the amount that the Bill deals involves ounces, or “z’s,” some might consider him to be a regular marijuana dealer. But the fact is that he is only involved in such intricate deals, involving a total of four ounces to three different people in different amounts once every 3–4 weeks. Essentially, Bill deals to support his consumption, has a legal job that supports his living standard, and he does not seem inclined to expand his business. Bill’s selling mechanism also provides an example of how those involved in private marijuana sales not only include the profit-driven entrepreneur, but also the casual user-seller (Valdez & Sifaneck, 2004), who plays a significant role in the distribution of marijuana to those not inclined to engage in other types of sales.

Marijuana Storefronts

These include many legitimate-appearing enterprises that also sell marijuana. Newsstands, candy stores, boutiques, record shops, video rental outlets and take-out restaurants which also sell marijuana have been common in New York City’s inner-city neighborhoods for over thirty years (Hamid, 2002). Storefronts did have a presence in Downtown Manhattan in the late 1980s and 1990s, but Tactical Narcotics Teams (TNT) effectively shut many of them with violations of the nuisance law (Johnson, Golub, Dunlap, Sifaneck, & McCabe, 2006; McCabe, 2005). Ethnographers observed a limited number of storefronts in the neighborhoods of Harlem, Washington Heights and inner-city Brooklyn. The following field note describes the setting and operation of a storefront on the Lower East Side, which operated at a high volume from 1992–1995, until police shut it down.

The boutique is the busiest business on this downtown block. The front window display includes Malcolm X hats, t-shirts, Rastafarian flags and hats, and incense. One shirt reads “Nelson Mandela! From Prisoner to President!” The facade has much in common with other boutiques which do not sell marijuana. Customers must ring the doorbell to enter the always-locked front door. Then the eyes of a African-Caribbean male in his late 20’s peer out, checking to see a familiar face and not “five-O,” a slang term for the police. After the security glance, the customer is buzzed in. Inside the small street level shop is a glass display case filled with Rastafarian style wares. On the back wall hang a number of t-shirts. The customers must slide the shirt furthest to the left to the side, where they find a small hole in the wall. Here a ten or twenty dollar bill is inserted, and a “dime” or a “twenty,” respectively, is pushed out from the other side of wall. “Dats some good shit for ya, my broda,” the male behind the wall says with a thick island accent. The customer, a white male student in his early 20s, quickly puts away the small sealed pillow-shaped ziplock bag without examining it, and leaves the store.

The storefront offers many advantages parallel to legal markets. Rarely does the customer get “burned” or “taken,” since the reputation of the storefront is at stake with each customer. Unlike the street market, where dealers rotate in and out, storefronts tend to be manned by familiar faces. Inside the storefront described above, a number of security precautions are taken to guard against robberies and police raids. While a known customer is buzzed in, potential robbers and police do not gain entry. In case of a raid, there is a brick wall and a steel door between the customer or cop and the person selling the marijuana. If police were to gain entry through the front door, which is locked and opened electronically, the seller(s) can escape through the back door behind the security wall.

Delivery Services

Another mechanism found in New York City is the delivery service. These services are run like take-out restaurants: the customer phones in his or her order, and within an hour the product arrives. Perhaps the most famous of these services was run by Michael “the Pope of Pot” Cesar in the mid-1990s. It featured a toll free number (1-800-WANTPOT). Cesar reportedly had six phones operating which received 360 calls per hour. Deliveries are made to apartments, offices, studios, and galleries. A new customer must be referred to a delivery service by a customer in good standing. The marijuana sold is high priced, ranging from $50 to $80 for an eighth of an ounce. Such deliveries are very convenient for the artists, private university students, lawyers, doctors, professors, brokers and other professionals who can afford it. A number of delivery services presently operate within Manhattan and Brooklyn, with most servicing more affluent areas. Some of these services had their origins in the “smoke-ins” and “pot-parades” of the 1970’s, where cards with delivery service phone numbers were distributed throughout the crowds of participants. These early protests drew thousands from inside and outside the metropolitan area, and were obviously ideal for the development of such marginal sales networks. Some used creative names (i.e. “Weed Deliver”) and marketing strategies such as offering diverse varieties and occasionally selling psilocybin (psychedelic mushrooms).

One common characteristic of a delivery service is its subtle operation. Deliveries by bicycle and foot are very common in New York City, and cannabis deliveries are indistinguishable to third-party observers from deliveries of other, legal products. Some delivery services have a corporate-like structure with an owner or proprietor, shareholders, and various employees who perform duties like phone operation, packaging, and delivery. The following field note provides an illustrative example designer marijuana service that demonstrates this corporate structure on a small scale:

Green Trees is a marijuana delivery service that operates out of Manhattan, servicing both the uptown and downtown areas. It is a small-scale operation, with 10 employees including the owner, the manager, the dispatcher and the runners. The way it operates is as follows: The client calls a phone number set up for a dispatcher. It is an unlisted phone number, such as one that comes with a pre-paid cell phone. The dispatcher then gets the client’s information and checks this information against a database either on a computer or in a book of some sort. If the information is matched to the client, the dispatcher will then call the runner in order to give him the client’s information. The influx of new clientele is not usually that heavy, so typically the client is someone the runner is familiar with… Green Trees typically delivers to their clients within a half hour of the initial phone call. The runners at Green Trees work on commission, making $10 on every $50 cube of marijuana they deliver. There is a manager who packs the runners up with the product for the day and closes them out in the evening. Green Trees operates between the hours of 12 pm and 12 am seven days a week, and there are two managers that work three to four days a week. In the evening, when the runner is closed out for the day, he will take his commission and return the product that was not sold. The managers usually hold several days worth of the product, for this enables them to have less interaction with those above them in the structure, such as the owner and the wholesale providers. Green Trees originally acquired their clients through promotions when the company first opened for business. The owner and some friends networked with others in social settings such as bars, clubs, and parties.

Other delivery services are more informal or homegrown. Some are even completely “owner-operated,” where one person purchases their designer marijuana from a wholesale source and then simply delivers it themselves to their list of clients, many of whom are people known within the seller’s social and work networks. The following provides a description an owner-operated delivery services that exclusively sells designer marijuana:

Barry moved to New York City from London three years ago. In London, he owned and managed a number of apartment buildings. When he arrived in New York City, he purchased a retail designer marijuana sales operation from a friend and fellow expatriate, whose sole occupation was selling designer marijuana. He did not actually purchase the operation, but traded one of his properties, a loft in central London, for ownership of the operation. Barry currently has 200 customers on a rotating basis. He sells anywhere between one and five varieties or strains of designer marijuana at a time. He charges $80 for 1/8 of an ounce, which is 3.5 grams. He delivers the marijuana by himself, and occasionally, employs a friend when he is out of town. He works Monday through Friday from about 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. although these hours are adjusted according to his clients’ needs and his personal schedule. He lives in New Jersey, takes the path train to Manhattan. He stores his wares in a friend’s local business in downtown Manhattan. He does this so as to avoid the harsher penalties for marijuana possession in the state of New Jersey. Barry purchases a monthly Metrocard which allows him to travel the subways and buses in the five boroughs for $72. He carries his designer marijuana in a Tupperware container. The container is put into small knapsack, which he carries on his back. Only marijuana in pre-weighed “eighths” is in the knapsack, this is done in case he has to ditch the contraband and potentially avoid arrest. At times, the retail value of the designer marijuana in the knapsack can easily amount to between $1500 and $2500. Barry’s carefully maintains his appearance to hide his work. He is of medium non-threatening build, dresses in casual yet expensive clothes, and possesses a distinct English accent. He only accepts customers who are working professionals (actors, businessmen, artists, lawyers, and doctors). His affluent appearance and cultivated manners makes his customers more at ease, when he enters their residences or workplace.

Barry is representative of a common way that designer marijuana is presently being sold at the retail level. The manner in which Barry operates keeps his sales operation very private so that he never arouses the suspicion of the police, nor the nonusers around his customers. Barry can keep his prices high ($80 for 3.5 grams) and still be competitive in the city’s Downtown market.

Designer marijuana purchased from delivery services is generally sold in $50 units containing 2 to 2.5 grams; this unit is often referred to as a “fifty” or “cube,” and often customers will buy multiple $50 units. Sometimes, delivery services sell units greater than $50. The packaging of designer marijuana is different than marijuana previously packaged in the 1970s and 1980s, when the product was often packaged small zip locked bags, and occasionally even in small brown paper bags. This type of packaging, however, is not appropriate for designer marijuana for a number of reasons. Designer marijuana dealers, often opt to put their product in small plastic boxes often referred to as “cubes.” These “cubes” come in an array of sizes, shapes, and colors. Sometimes these boxes are double sealed to preserve the freshness of the product and to make sure there is no tampering in the delivery process. These boxes serve the function of maintaining the freshness and integrity of the expensive marijuana; integrity being that the buds of marijuana are moist, intact, and not crushed against each other. Designer marijuana sellers (especially delivery services) rarely sell or package “shake”—loose marijuana leaf outside of the bud format.

1.3 Pricing and Measurement Issues

Many researchers rely on measures of price and weight quantity based on what their respondents self-report (Community Epidemiology Work Group [CEWG], 2005, January; Marel, 2005; Schensul, Huebner, Singer, Feliciano, & Broomhall, 2000). There are many problems with this approach. For one, people usually always know the price they are paying for a retail unit (although this may be inflated through middlepersons) but they usually do not weigh the quantity. The represented quantity may also be less than the actual quantity. Users often get measurement units confused. How many ounces are in ¼ pound? Is a ¼ ounce the same as 7 grams? How many grams are in an ounce? These are common questions within the marketplace. Users are accustomed to pay a certain amount of money; they often refer to retail unit of the product with argot-terms like “twenties,”($20) “dub sacs,” ($20) “nickels,”($5) “dimes”($10) “quarters” ($25 or ¼ ounce) and “cubes” ($50) (for more discussion of marijuana argot, see Johnson, Bardhi, Sifaneck, & Dunlap, 2006). Even though this argot is usually understood by the buyer and seller, it is common for the buyer, and sometimes the seller, not to know the actual weight as measured by a scale.

Economic studies of pricing have relied primarily upon Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) buys and police seizures of confiscated marijuana. Among the problems with law enforcement data (NRC, 2001) is that it often combines measurements of wholesale and retail seizures of the drug. Law enforcement data also, when they contain information about the quality of the product at all, make much rougher distinctions than the users themselves do. The Drug Enforcement Administration (2003) makes distinctions between “commercial grade,” “sinsemilla,” and “BC Bud” from British Columbia. This trichotomy does not adequately describe the other designer strains in the market. Given the fact that many commercial grade strains of marijuana are in fact “sinsemilla” (Spanish word for “without seeds”) it also fails to adequately distinguish commercial from designer grades of the drug.

The Office of National Drug Control Policy (2004) mentions the distinction between commercial grade and sinsemilla. However, from the System to Retrieve Information from Drug Evidence (STRIDE) data, it reports a single average price ($325 per ounce in 2003) and does not report this figure separately by quality. Contrast this with the users’ own data sources: High Times, popular among marijuana consumers for its glossy photos of designer strains and monthly marijuana prices, provides readers’ reports of price-per-ounce of several specific designer strains in their Trans-High Market Quotations (Peet, 2005). Even these are only of limited use in understanding how much users are actually paying on the retail level because very few retail purchasers of designer marijuana buy an entire ounce at a time. The Trans-High price is most likely that paid by a user-seller (like Bill or Barry).

The review of the scientific literature turned up no studies of the weights of actual retail purchases or the prices paid for them. Being uniquely situated to study this because of the ongoing work on marijuana subcultures, we conducted a sub-study to document the circumstances and characteristics of actual retail marijuana purchases.

1.4 Specific Hypotheses

The research objective of this study is to document the bifurcation of the marijuana market between commercial and designer sectors with respect to purchaser characteristics, neighborhoods in which they are purchased, units in which they are packaged, and price per gram. Specific hypotheses include a) significant bivariate associations exist between price per gram and perceived marijuana quality, purchaser’s race, purchaser’s gender and age, purchase location, dealer type, and sales unit. B) perceived quality explains variance in price per gram over and above purchaser characteristics, purchase location, dealer type, and unit size.

A complete and clean division in the markets is not expected. Without a large and representative sample of marijuana purchases, which is impossible for many reasons, these data cannot meaningfully address questions about prevalence of one purchase type over another. Rather, with a relatively large and diverse purposive sample of purchases, we hoped to empirically demonstrate what we had already observed ethnographically: the bifurcation between commercial and designer marijuana markets with respect to price, common units of sale, and purchaser characteristics.

2. Methods

2.1 Recruitment of Marijuana Users with Retail Purchases

Over a 9-month period in 2005, an African-American ethnographer recruited 41 participants in the uptown areas of Harlem, Washington Heights, and the Bronx. A white ethnographer recruited 58 participants in downtown Manhattan (East Village/Lower East Side, Union Square, Chinatown, Chelsea, Soho). Both ethnographers had already been in the field for several years as part of our ongoing work on marijuana subcultures. Each participant was a consumer who made his/her own purchases of marijuana and willingly agreed to meet the ethnographer in a private location where their recent retail purchase could be weighed. Staff measured 99 different retail marijuana purchases from 96 different marijuana consumers.

2.2 Procedures

Ethnographers had respondents weigh their retail marijuana purchase on a digital scale which measures to the nearest hundredth (.01) of a gram. After the respondent with a recent retail purchase was present in a private location, the ethnographers followed a strict protocol to make direct observations, ensure accurate weighing of product, and to protect themselves from any legal liability. All measurements were done in private and safe locales; no measurements were made in public locations. Respondents maintained possession of their product and ethnographers maintained possession of the scale. At no time during the observations did ethnographers have possession of the product. Respondents first separated the product from the packaging container, and. the weight was only taken of the product, and not the packaging. If the total product did not fit on the scale platform, the respondents weighed the package that contained the product and the weight of the packaging was then subtracted from the total weight of the product and the package. The price paid was divided by the net weight of each specimen, as recorded on the scale, to obtain price per gram. These price-per-gram measurements can be compared to national data collected at the same user-based retail levels (Drug Enforcement Administration, 2003; Office of National Drug Policy, 2004).

2.3 Measures

These respondents also provided researchers with systematic information regarding the sales unit bought, actual price paid, type of sale, where the product was purchased, and the quantity of marijuana they believed they were buying. In addition, our ethnographers carefully observed each purchase for quality and “graded” it as an independent but expert observer separate from the respondent’s report (as described further below). This information provided the independent variables analyzed below:

Location

Uptown included lower income areas such as Harlem, Washington Heights, and the Bronx. Downtown included more affluent neighborhoods such as Union Square, the Lower East Side/East Village, Chelsea, Chinatown and Soho.

(Perceived) Quality

Ethnographers directly observed and recorded descriptions of what the marijuana looked and smelled like. From these descriptions the quality of the marijuana was graded into 6 categories. “C−” marijuana was characterized as low-grade commercial marijuana, where seeds and stems were present, and often the product was observed to be dry, and without any distinct aroma. “C” marijuana was characterized as middle grade commercial marijuana. All of the samples of commercial grade marijuana had been “pressed,” that is compressed into space efficient bricks for smuggling and transport. None of the designer marijuana observed demonstrated this characteristic of being pressed. “C+” marijuana was upper-grade commercial marijuana in which few seeds or stems were observed, but the product still maintained its “pressed” appearance. “D−” marijuana was characterized by lower grade designer marijuana, where it seemed that it was grown either hydroponically indoors or in ideal outdoor conditions, but did not meet the standards of higher end designer grades. “D” marijuana was characterized by average quality designer marijuana, grown indoors, usually with pungent aromas. “D+” marijuana was characterized by top quality designer strains, almost always sold by a specific strain name.

Sales Units

Units sold by price included $5 “nickel” bags, $10 “dime” bags, $20 bags, $50 bags, and “cubes.” $50 bags and cubes were combined because all the cubes were $50. Units sold by weight were eighth ounces (3.5 grams), quarter ounces (7 grams), half ounces (14 grams), and ounces (28 grams).

Seller Type

Respondents reported buying from delivery services, street sellers, private sellers, and storefronts.

3. Results

Two-fifths (39%) of purchases were made by Blacks, 31% by whites, 13% by Latinos, 11% by Asians, and 5% by people of mixed races. Three-fifths of the purchases were made by males. About two-fifths were made in “Downtown,” i.e., gentrified or relatively affluent, locations. Most purchases overall were from street (37%) or private (38%) sellers, with delivery services accounting for fewer purchases (18%). Purchases of $5 “Nickel” bags, $10 “Dime” bags, $20 “Twenty” bags, “Fifty” bags or cubes, “Eighths” or 1/8-ounce units (3.5 grams), and “Quarters” or ¼-ounce units (7 grams) occurred at roughly similar rates: Each of these units comprises between 12% and 19% of our sample. Table 1 indicates the number of purchases in each group. Percentages are very close to actual n because there were 99 observations.

Table 1.

Bivariate Association between Marijuana Type, Price Per Gram, and Other Study Variables

| Perceived Quality

|

Bivariate Association | Price per Gram

|

Bivariate Association | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | N | Commercial | Designer | Commercial | Designer | Mean | ||

| Race | Mixed | 5 | 40% | 60% | χ2 = 8.60+ | $5.53 | $20.79 | $14.69 | F = 7.26 *** |

| Asian | 11 | 55% | 46% | $11.03 | $16.97 | $13.73 | |||

| Latino | 13 | 46% | 54% | $7.58 | $17.68 | $13.02 | |||

| Black | 39 | 67% | 33% | $7.11 | $13.95 | $9.39 | |||

| White | 31 | 32% | 68% | $10.24 | $20.51 | $17.20 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Gender | Male | 60 | 55% | 45% | χ2 = 1.23 | $8.05 | $17.32 | $12.22 | t = −1.54 |

| Female | 39 | 44% | 56% | $8.50 | $18.89 | $14.36 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Location | Uptown | 42 | 62% | 38% | χ2 = 3.79 + | $6.95 | $15.57 | $10.23 | t = −3.78 *** |

| Downtown | 57 | 42% | 58% | $9.55 | $19.22 | $15.15 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Dealer | Delivery | 18 | 11% | 89% | χ2 = 16.66 ** | $9.34 | $21.48 | $20.13 | F = 12.87 *** |

| Type | Street | 37 | 68% | 32% | $7.51 | $15.50 | $10.11 | ||

| Private | 43 | 54% | 47% | $8.84 | $17.49 | $12.87 | |||

| Storefront | 1 | 0% | 100% | $3.58 | none | $3.58 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Unit | Nickel | 19 | 100% | 0% | χ2 = 37.20 *** | $6.94 | none | $6.94 | F = 8.32 *** |

| Size | Dime | 12 | 42% | 58% | $8.24 | $14.06 | $11.64 | ||

| Twenty | 15 | 60% | 40% | $7.11 | $21.28 | $12.78 | |||

| Fifty/Cube | 16 | 6% | 94% | $7.76 | $20.31 | $19.53 | |||

| Custom/wt | 5 | 40% | 60% | $10.15 | $23.77 | $18.32 | |||

| Eighth | 14 | 36% | 64% | $10.95 | $17.99 | $15.47 | |||

| Quarter | 12 | 42% | 58% | $12.89 | $15.41 | $14.36 | |||

| Half Ounce | 3 | 100% | 0% | $5.70 | none | $5.70 | |||

| Ounce | 3 | 33% | 67% | $8.61 | $5.64 | $6.63 | |||

2-tailed (when applicable)

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001. Some row totals do not add up to 100% due to rounding error.

We calculated price per gram for units sold by weight based on the actual weight of the unit, not the weight that the unit was supposed to have. Thus, we base calculations on what the participant actually got, not what they thought they were getting. This is an important distinction because actual weights of purchases ranged from 11% above to 24% below the weight the respondent had been led to believe. About 75% of the specimens were 90% or less of their seller-alleged weight. The average price per gram for commercial marijuana was $8.20 and, for designer marijuana, $18.02, and this difference was statistically significant, t = 10.35, p < .001. Table 1 describes several aspects of the sample as well as bivariate relationships between race, gender, location, dealer type, unit size, quality (commercial or designer), and price per gram.

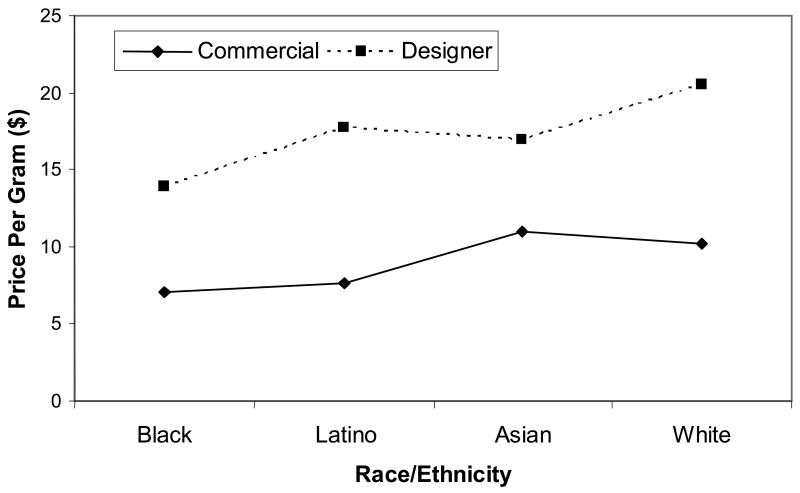

Table 1 also indicates bivariate associations between quality, price per gram, and other variables. Within each category of the variables, the price paid per gram appeared to vary largely as a function of the proportion of designer vs. commercial purchases. Purchases made by blacks, compared to purchases made by other racial groups, were the lowest price per gram ($9.39) and were least likely to be designer purchases. Purchases made by whites had the highest price per gram ($17.20) and the most likely to be designer purchases. Purchases made in downtown areas are an average of $5 more expensive per gram than purchases made uptown. Delivery service purchases are the most expensive per gram ($20.13) and are almost always (89%) designer; street purchases are the least expensive per gram ($10.11) and the least likely (32%) to be designer. Of all purchase unit types, fifties/cubes were most expensive per gram ($19.53) and are almost exclusively (94%) a designer unit. Commercial nickel ($5) bags and half-ounces were the least expensive per gram of the units observed. The nickel bags observed were all commercial units.

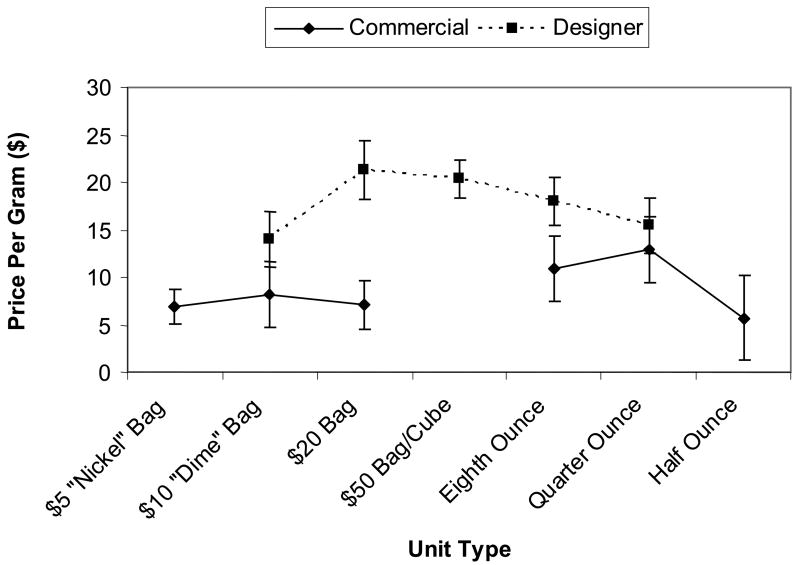

Figure 1 illustrates the average price of common retail units. Cell means are excluded from this graph that is based on less than 3 cases. Some cell means are conspicuous by their absence: We collected no designer $5/nickel bags and only one commercial $50 bag. Of the six $50 “Cube” (not bag) units that we found, all were designer. Only one commercial and two designer ounces were reported by respondents, which is unsurprising because an ounce is rarely a retail unit of any type of marijuana.

Figure 1.

Average Price per Gram of Marijuana Retail Units.

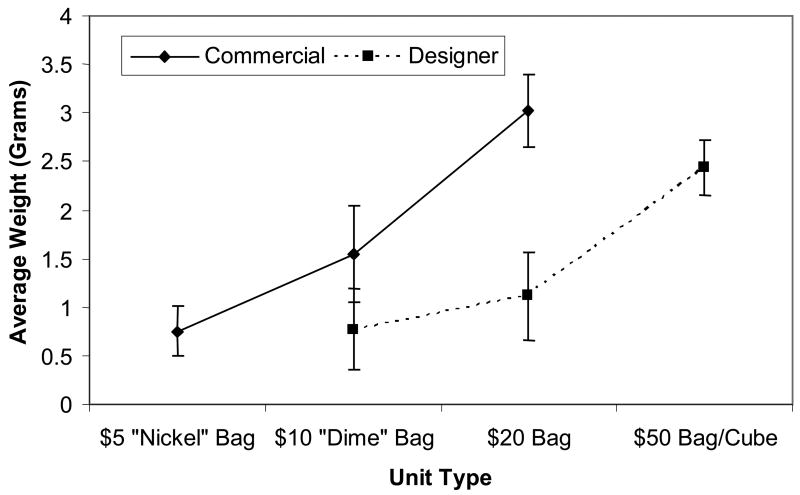

Figure 2 addresses the question of value for money from another direction: Weight of the units that are sold by price. This graph does not include the price per gram of the one commercial $50 bag. Commercial $10 and $20 bags contain slightly more than twice the weight of marijuana as designer $10 and $20 bags. The $5/nickel bag is an exclusively commercial unit, and was only observed to be sold uptown. It contains an average of 0.75 grams, which is about the same amount in the average designer $10/dime bag.

Figure 2.

Average Weight of Retail Marijuana Units Sold by Price.

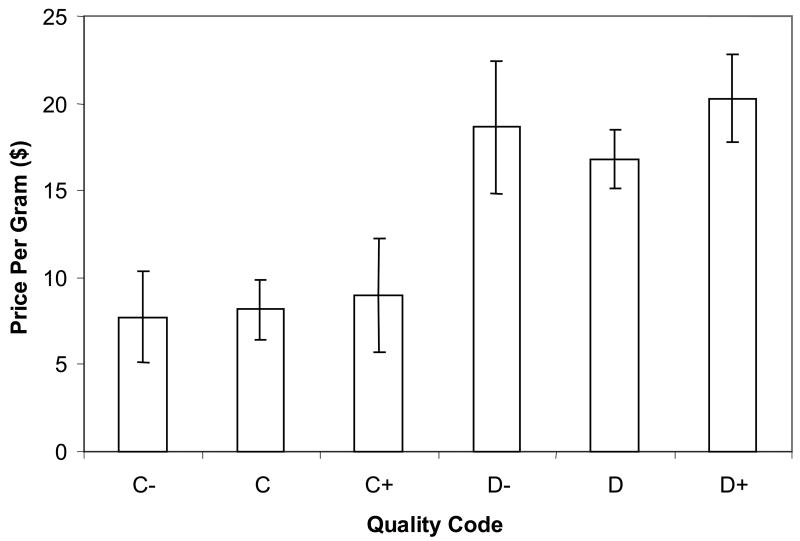

Figure 3 presents mean price per gram for each quality grade of marijuana as observed by our ethnographers, according to the distinctions described above. In further support of hypothesis 1, the Pearson correlation coefficient between quality grade (treated, for the moment, as a linear variable) and price per gram is .710. Figure 2 indicates a fairly linear association between quality grade and price per gram. Low-grade commercial “C−” marijuana was an average of $7.75/gram, and high quality commercial (C+) was $9.00, while high-end designer “D+” marijuana was an average of $20.29/gram.

Figure 3.

Price per gram for each quality grade of marijuana.

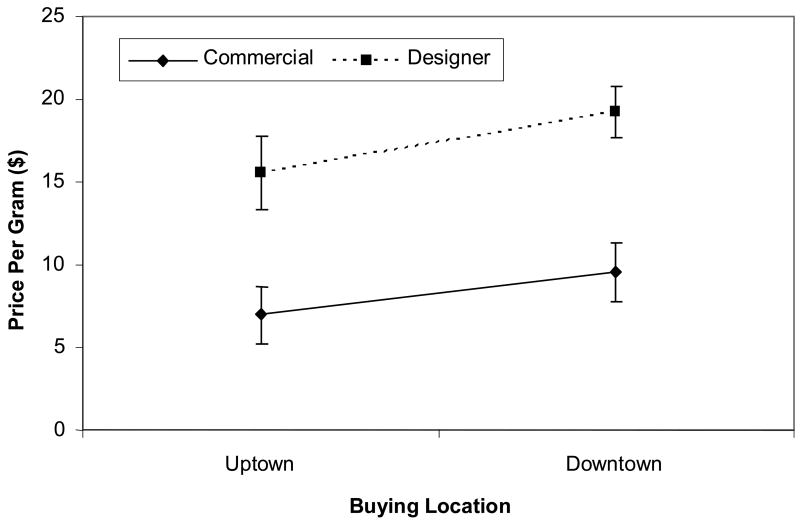

Table 2 reports the results of a general linear model with price per gram of the purchase as the dependent variable and race of purchaser, dealer type, unit sold, marijuana type, and location as independent variables. We left age and gender of purchaser out of these analyses because they had no linear association with either marijuana type or price per gram. In order to maintain adequate cell size, only those unit sizes for which we had at least five designer and five commercial purchases – $10 bags, $20 bags, eighth ounces, and quarter ounces – were included. Individual regression slopes as well as the variance in price per gram explained by the entire factor are reported. Although all factors in this analysis have a significant bivariate relationship with price per gram, as described in Table 1, only quality – commercial vs. designer – explains a significant amount of variance. Race and location reach trend level but are not statistically significant. Figure 4 describes the relationship between the roles of quality and buying location in determining price per gram. Figure 5 describes the relationship between the roles of buyer’s race/ethnicity and buying location in determining price per gram. Neither interaction effect was statistically significant.

Table 2.

Variance Explained in Price Per Gram Controlling for Quality, Unit Type, Location, Dealer Type, and Purchaser’s Race

| Individual Regression Slope

|

Variance Explained by Factor

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | F | ||

| Race | Mixed | .817 | 2.242 + |

| Asian | .340 | ||

| Latino | −5.557* | ||

| Black | −5.857* | ||

| White | (ref) | ||

| Dealer Type | Delivery | 2.059 | .487 |

| Street | .108 | ||

| Private | (ref) | ||

| Unit Sold As | Dime/$10 | −2.690 | 1.099 |

| Twenty/$20 | .594 | ||

| Eighth Oz. | 2.462 | ||

| Quarter Oz. | (ref) | ||

| Quality | Commercial | −6.501*** | 14.570 *** |

| Designer | (ref) | ||

| Location | Downtown | 5.222+ | 3.405 + |

| Uptown | (ref) | ||

| Intercept | 16.712*** | ||

|

| |||

| Model Fit | Adj. R2 | .420*** | |

p <.10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Figure 4.

Mean Price Per Gram as a Function of Quality and Location

Figure 5.

Mean Price Per Gram as a Function of Quality and Purchaser’s Race/Ethnicity

Table 3 is the most detailed analysis we offer, describing mean price per gram for each specific commercial and designer variety separately by the variables that were marginally significant in the analysis described in Table 2: buyer’s ethnicity and location of purchase. Buyer’s ethnicity was dichotomized into White/Asian/Mixed and Black/Latino for ease of presentation. According to chi-square tests, within region, quality was independent of buyer’s ethnicity operationalized either as this dichotomy or the full five-category variable. The most striking difference among purchases emerging from this table is that our participants bought different varieties of marijuana from uptown rather than from downtown, and paid different amounts for the same quality marijuana uptown than downtown.

Table 3.

Mean Price Per Gram of Specific Varieties by Location and Purchaser’s Race/Ethnicity

| Uptown

|

Downtown

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White/Asian/Mixed

|

Black/Latino

|

White/Asian/Mixed

|

Black/Latino

|

||||||

| Mean $/gram | N | Mean $/gram | N | Mean $/gram | N | Mean $/gram | N | ||

| Commercial Varieties: | Commercial Unspecified | $ 3.30 | 1 | $ 6.71 | 11 | $10.03 | 13 | $ 7.92 | 4 |

| Commercial “Chronic” | $ 8.43 | 2 | $ 7.63 | 2 | |||||

| Commercial “Haze” | $14.54 | 2 | $ 5.99 | 1 | |||||

| Arizona | $ 7.20 | 10 | |||||||

| Chocolate | $ 7.91 | 4 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Designer Varieties: | Designer Unspecified | $35.09 | 1 | $17.96 | 11 | $16.60 | 2 | ||

| Purple Haze | $19.23 | 1 | $13.34 | 4 | |||||

| Skunk | $ 8.68 | 6 | |||||||

| Haze | $22.32 | 4 | $19.92 | 1 | |||||

| Trainwreck | $17.54 | 1 | |||||||

| Juicy Fruit | $18.91 | 4 | |||||||

| White Widow | $19.64 | 4 | |||||||

| Sour Diesel | $22.09 | 4 | $18.69 | 3 | |||||

| Sweet Diesel | $21.19 | 1 | |||||||

| Humboldt | $22.86 | 1 | |||||||

| Super Jack (Herer) | $23.26 | 1 | |||||||

Basic commercial marijuana was 48% more expensive per gram downtown than uptown, which is unsurprising because everything else is more expensive downtown. We found commercial “Haze” and “Chronic” only downtown, suggesting that dealers realize designer labels are salient in that market and were attaching “designer” strain labels to commercial grade marijuana as a marketing technique. Arizona and Chocolate varieties were found exclusively uptown. These labels do not refer to specific strains but rather their origin, i.e., Arizona is Mexican commercial-grade marijuana commonly smuggled via Arizona, and Chocolate is grown in Jamaica. Buyers did not pay designer prices for Arizona and Chocolate, indicating that dealers did not represent them and buyers did not believe them to be designer strains. There was a significant race difference within regions: White/Asian/Mixed people downtown pay an average of $2.81 more per gram than Black/Latino people downtown and $3.28 more per gram than Black/Latino people uptown, and these differences are significant according to a Least Significant Differences test post-hoc to a one-way ANOVA involving the three groups. To distinguish the groups even further, Asians paid the most per gram ($11.03) for commercial marijuana downtown, followed by whites ($10.24), then Latinos ($8.57), and finally Blacks ($6.80). Future research involving larger sample sizes and greater statistical power will probably find these differences to be significant.

While the commercial market appeared to be bifurcated by price, the designer market appeared to be bifurcated by availability of specific products. The only designer varieties we found uptown were Skunk, Purple Haze, and Haze. Although these are legitimate strain names and the product observed was of designer quality, it is more likely that they were marketing labels used generically to denote a high-quality product. Only downtown did brand labels like White Widow, Sour Diesel, Super Jack, Juicy Fruit, and Trainwreck describe specific premium designer strains that are meaningful to knowledgeable customers.

4. Discussion

Although purchaser’s race, dealer type, sales unit, quality, and location all exhibit significant bivariate relationships with price per gram, the designer vs. commercial distinction is the only factor that explains a significant amount of variance in price per gram independently of these other factors. Designer marijuana purchases were more than twice as expensive per gram as commercial purchases ($18.02 vs. $8.20). Commercial units sold by price were slightly more than twice as heavy as comparable designer units sold by price (1.6g vs. 0.8g for $10 bags, 3g vs. 1.1g for $20 bags). Two-thirds of purchases by whites were of designer and one-third was of commercial marijuana. One-third of purchases by Blacks was of designer and two-thirds were of commercial marijuana. All of the $5 bags we found were commercial and all of the $50 “cubes” were designer. Delivery service purchases were more likely to be designer than commercial, and street purchases were more likely to be commercial than designer.

Separate analyses by race and location suggest further divisions within or perhaps across the commercial/designer distinction. Commercial marijuana was, as far as we could tell, not any higher quality downtown than uptown, but it was more expensive, and people who were neither Black nor Latino appeared to be paying a premium. The blacks and Latinos uptown buying commercial marijuana were, however, not ignorant of what they were getting. They described it as Arizona or Chocolate more often than as generic “shwag” or “street weed” which we called (“commercial unspecified”), indicating that they knew its origin, yet did not pay any more for Arizona or Chocolate than for generic commercial marijuana. The designer market appeared to actually be bifurcated by location, with different and higher-quality brands available uptown than downtown. It is no coincidence that this area of New York City is well known to be predominantly white and affluent. Downtown, commercial marijuana was occasionally marketed with a dubious brand name (Haze, Chronic) attached to it, suggesting that dealers apply the brand names to make otherwise-ordinary marijuana appealing to downtown buyers who are interested in brand-name goods. Our evidence does not suggest that this enabled it to fetch a higher price.

These findings about the pricing, and retail purchase units, suggests several interesting features of the illicit markets for marijuana in New York City. Commercial marijuana is still an order of magnitude more expensive than its closest legal analog, tobacco, specifically because the hazard pay due to the producers, importers, and sellers of an illegal product gets exacted from consumers. In New York City specifically, quality of life policing practices target individuals selling or using even small amounts of marijuana in public (Golub, Johnson, & Dunlap, 2006). Staying out of trouble is expensive, and the more discrete methods of producing and selling marijuana characteristic of the designer market (Caulkins & Pacula, 2005) permit designer marijuana to fetch an even higher price.

The data did not bear out our expectation that buyers routinely ended up with lower quality marijuana than they had expected out of the deal. In only a couple of the purchases did the ethnographer’s evaluation of the quality differ substantially from the buyer’s estimation, which is why these two measurements were not considered separately in the analyses (for purposes of this study, differences were resolved in favor of the ethnographer). Users do not get cheated in quality as much as they do in quantity: the average purchase sold by weight was 5% lighter than the end-user thought it was (range 24% lighter to 11% heavier). It is also worth noting that there is no obvious economy of scale, i.e., higher quantities were not cheaper by the gram.

Users are willing to pay more for the high-quality marijuana because they believe it is more potent. Although our analyses definitely show an effect of perceived quality on price, we cannot confirm, independently of users’ testimonies, a relationship between quality and THC content. Actually measuring THC content would have been cost-prohibitive for a study on this scale but should definitely be done in future research.

Not knowing the precise THC content does not prevent marijuana sellers from commanding a high price for their perceived-to-be premium product, which also carries prestige within marijuana-using social groups. They claim to sell a prestigious strain name that connoisseurs of cannabis should know and understand. They also promote how rarely these fine products are available and perhaps make reference to glossy pictures of cannabis in publications for marijuana enthusiasts. This enables designer sellers to fetch very high market prices. Designer marijuana sellers also carefully limit and carefully screen their pool of steady customers and gain new customers only from those referred by their existing affluent marijuana customers. This casts an air of exclusivity around the seller and reduces the seller’s exposure to law enforcement. Their affluent clientele also have little or no desire neither to locate street sellers nor to purchase poorer quality marijuana. In large measure, the relatively affluent marijuana consumer pays a premium price to: avoid any involvement with a person whom the police may arrest, have no contact with (and avoid) street markets, get “free” delivery of this illegal product, and receive assurances that the seller is delivering a premium strain of marijuana (even in the absence of information about actual THC levels).

In conclusion, future research that can systematically and accurately measure THC potency in retail marijuana purchases and can also measure various dimensions of users’ perception of marijuana quality and the prestige accorded to various strains will be needed to increase scientific understanding of this aspect of retail marijuana markets. Drug researchers in other geographic locations should try to replicate or construct similar methodologies that would allow price comparisons of marijuana across regions. Additional scientific information about the potency, or percent of THC, of designer marijuana in typical retail units would be very important for documenting whether how much is being consumed by purchasers to address several important scientific questions: Are those smoking designer marijuana using the same amount as commercial marijuana smokers? How much does THC potency influence the frequency of smoking? Are those smoking higher THC cannabis more likely to need treatment for marijuana misuse?

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this paper was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1R01 DA/CA13690-03), and by National Development and Research Institutes. From April 2005 through August 2006, the second author was supported as a postdoctoral fellow in the Behavioral Sciences Training in Drug Abuse Research program sponsored by Medical and Health Association of New York City, Inc. (MHRA) and the National Development and Research Institutes (NDRI) with funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5T32 DA07233). Points of view, opinions, and conclusions in this paper do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Government, Medical and Health Association of New York City, Inc. or National Development and Research Institutes. The authors acknowledge with appreciation the contributions of Flutura Bardhi, Doris Randolph, James Hom, and Ellen Benoit to this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Stephen J. Sifaneck, Institute for Special Populations, Research National Development and Research Institutes, New York, NY 10010 USA

Geoffrey L. Ream, School of Social Work, Adelphi University, Garden City, NY 11530 USA

Bruce D. Johnson, Institute for Special Populations, National Development and Research Institutes, New York, NY 10010 USA

Eloise Dunlap, Institute for Special Populations, National Development and Research Institutes, New York, NY 10010 USA.

References

- Adler PA. Wheeling and Dealing: An Ethnography of an Upper-Level Drug Dealing and Smuggling Community. New York: Columbia University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Agar M. Ripping and Running: A Formal Ethnography of Urban Heroin Addiction. New York: Seminar Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade X, Sifaneck SJ, Neaigus A. Dope sniffers in New York City: An ethnography of heroin markets and patterns of use. Journal of Drug Issues. 1999;29(2):271–298. [Google Scholar]

- Auld J. Marijuana Use and Social Control. New York: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Becker HS. Marijuana Use and Social Control. Human Organization: Journal of the Society for Applied Antrhopology, Spring 1953 [Google Scholar]

- Becker HS. Outsiders Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. London: Macmillan Publishing; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnie RJHWC. The Marihuana Conviction: A History of Marihuana in the United States. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Castro RA. Behind closed doors at the mouse café: A subcultural enclave of coffee shop suppliers in Amsterdam. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1995;22(3):513–546. [Google Scholar]

- Caulkins JP, Pacula RL. Marijuana Markets: Inferences from Reports by the Houshold Population (Working Manuscript) Rand Corporation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Community Epidemiology Work Group (CEWG) Epidemiologic Trends in Drug Abuse: Advance Report. Washington D.C.: National Institute of Drug Abuse; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis R, Wendel T. Toward the development of a typology of illegal drug markets. In: Natarajan M, Hough M, editors. Illegal Drug Markets: From Research to Preventions Policy. Vol. 11. Crime Prevention Studies; 2000. pp. 121–152. [Google Scholar]

- Drug Enforcement Administration. Illegal Drug Prices and Purity Report. 2003 Retrieved August 6, 2006, from http://www.dea.gov/pubs/intel/02058/02058.pdf.

- Dunlap E, Johnson BD, Sifaneck SJ. Sessions, cyphers, and parties: Settings for informal social controls of blunt smoking. Journal of Ethnicity and Substance Abuse. 2005;4:43–80. doi: 10.1300/J233v04n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eck JE, Gersh JS. Drug trafficking as a cottage industry. In: Natarajan M, Hough M, editors. Illegal Drug Markets: From Research to Preventions Policy. Vol. 11. Crime Prevention Studies; 2000. pp. 241–272. [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD, Dunlap E. The racial disparity in misdemeanor marijuana arrests in New York City. Criminology and Public Policy. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2007.00426.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid A. The Ganja Complex: Rastafari and marijuana. Cumnor Hill, Oxford: Lexington Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton J. Receiving marijuana and cocaine as gifts and through sharing. Substance Use and Misuse. 2005;40(3):361–368. doi: 10.1081/ja-200030548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen ACM. Cannabis in Amsterdam: A geography of hashish and marijuana. Mulderberg: Coutinho; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen ACM. The development of a ‘legal’ consumers’ market for cannabis: The ‘coffee shop’ phenomenon. In: Leuw E, Marshal IH, editors. Between Prohibition and Legalization: The Dutch Experiment in Drug Policy. New York: Kugler; 1994. pp. 169–181. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD. Marijuana Users and Drug Subcultures. New York: Wiley; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Bardhi F, Sifaneck SJ, Dunlap E. Marijuana argot as subculture threads: Social constructions by users in New York City. British Journal of Criminology. 2006;46(1):46–77. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Goldstein PE, Schmeider J, Lipton DS, Spunt . Taking Care of Business: The Economics of Crime by Heroin Abusers. Lexington: Lexington Books; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Golub A. The potential for accurately measuring behavioral and economic dimensions of consumption, prices, and markets for illegal drugs. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.005. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Golub A, Dunlap E. The rise and decline of drugs, drug markets, and violence in New York City. In: Blumstein A, Wallman J, editors. The Crime Drop in America. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 164–206. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Golub A, Dunlap E, Sifaneck SJ, McCabe J. Policing and social control of public marijuana use and selling in New York City. Law Enforcement Executive Forum. 2006;6(5):55–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J. The Cannabible. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman MAR. Marijuana: Costs of Abuse, Costs of Control. Greenwood: New York Greenwood Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Knutsson J. Swedish drug markets and drugs policy. In: Natarajan M, Hough M, editors. Illegal Drug Markets: From Research to Preventions Policy. Vol. 11. Crime Prevention Studies; 2000. pp. 179–203. [Google Scholar]

- Korf DJ. Dutch coffee shops and trends and cannabis use. Journal of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:851–866. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblum W. Working the deuce. Yale Law Review: Spring; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Marel R. Epidemiologic Trends in Drug Abuse: Advance Report. Washington DC: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2005. New York Trends, Marijuana; pp. 56–57. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe JE. Unpublished PhD Thesis. City University of New York; New York: 2005. An examination of the effect of drug enforcement on the rate of serious crime in Queens County, NY from 1995–2001. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council [NRC] Informing America’s Policy on Illegal Drugs: What We Don’t Know Keeps Hurting us. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of National Drug Policy. The price and purity of illicit drugs: 1981-through the second quarter of 2003. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Parker H. How young Britons obtain their drugs: Drugs transactions at the point of consumption. In: Natarajan M, Hough M, editors. Illegal Drug Markets: From Research to Preventions Policy. Vol. 11. Crime Prevention Studies; 2000. pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Peet P. Trans-high market quotations (THMQ) reports pot prices (by the ounce), strain and location. High Times. 2005;357:16. [Google Scholar]

- Preble E, Casey JJ. Taking care of business: The heroin user’s life on the street. The International Journal of Addiction. 1969;4:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ream GL, Johnson BD, Sifaneck SJ, Dunlap E. Distinguishing blunts users from joints user: A comparison of marijuana use subcultures. In: Cole S, editor. Street Drugs: New Research. Hauppauge: New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2006. pp. 245–273. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes W, Sheiman HR. The price of cocaine, heroin, and marijuana 1981–1993. The Journal of Drug Issues. 1994;24(3):383–402. [Google Scholar]

- Schensul JJ, Huebner C, Singer M, Feliciano P, Broomhall L. The high, the money and the fame: The emergent social context of “New Marijuana” use among urban youth. Journal of Medical Anthropology. 2000;18:389–414. [Google Scholar]

- Sifaneck SJ, Johnson BD, Dunlap E. Cigars-for-blunts: Marketing of flavored tobacco products to youth and minorities. Journal of Ethnicity and Substance Abuse. 2005;4(34):23–42. doi: 10.1300/J233v04n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifaneck SJ, Kaplan CD. Keeping off, stepping on, stepping off: The steppingstone theory reevaluated in the context of the Dutch cannabis experience. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1995;23(3):513–546. [Google Scholar]

- Single E, Kandel DB. Drugs, crime and politics. In: Trebach A, editor. The Role of Buying and Selling in Illicit Drug Use. New York: Praeger; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez A, Sifaneck SJ. “Getting high and getting by”: Dimensions of drug selling behaviors among American Mexican gang members in South Texas. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2004;41(1):82–105. doi: 10.1177/0022427803256231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet HJ. Separation of drug markets and the normalization of problems in the Netherlands: An example for other nations. Journal of Drug Issues. 1990;20(3):463–471. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins C, Casswell S. Organized crime in cannabis cultivation in New Zealand: An economic analysis. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2003;30:757–777. [Google Scholar]

- Williams T. The Cocaine Kids. New York: Addison Wesley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Williams T. Crackhouse. New York: Addison Wesley; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wood E. Kids, drugs, and crime. In: Carpenter C, Glassner B, Johnson BD, Loughlin J, editors. Drug Selling and Dealing Among Adolescents. Lexington, MA: 1988. [Google Scholar]