Since the last issue of the Annals, the following letters have been published on our website <http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/publications/eletters/>:

We read with interest the case of digital ischaemia following a forgotten digital tourniquet.1 As mentioned, authors have previously described modifications to the technique to prevent leaving the tourniquet in place post-operatively.

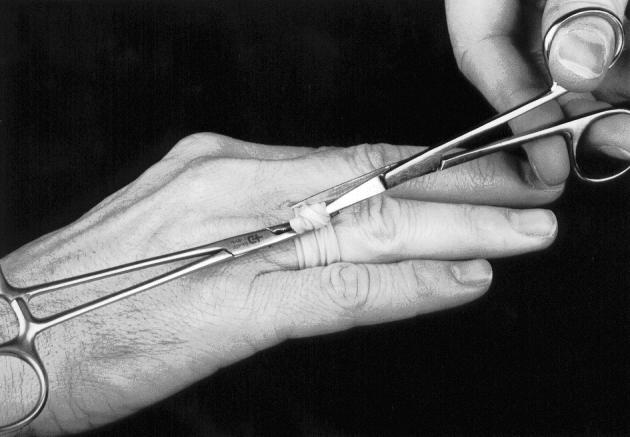

We would like to remind readers of this simple modification to the roll-on finger tourniquet technique. It is frequently used in our department and provides a simple and safe method for digital tourniquet. A finger is cut off a sterile rubber glove and its tip is removed. It is then rolled proximally to the base of the finger in order to exsanguinate the finger. The tourniquet is then grasped in an artery clip which is left in place with the handle pointing proximally (Figure 1). The rubber ring is then cut above the clip with scissors. This ensures that when the clip is removed at the end of the procedure the tourniquet is automatically released and cannot be left in place accidentally.2

Figure 1.

The rubbing ring cut above the clip

Footnotes

References

- 1.Durrant C. Forgotten digital tourniquet: salvage of an ischaemic finger by application of medicinal leeches. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:462–464. doi: 10.1308/003588406X117052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith IM. A simple and fail safe method for digital tourniquet. J Hand Surg [Br] 2002;27:363–4. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2002.0781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

We commend Mr Pinder et al. for their simple and reliable technique for ensuring that a digital touriquet is not forgotten.1 Having referred to several other methods in our original report,2 we apologise for the oversight in not including their particular paper in my list of references. I would heartily recommend their technique as among the best available in terms of ease and cost-effectiveness, but would advise readers to take care in the application of the artery clip so as not to put undue tension through the tourniquet, thereby causing harm to the underlying neurovascular bundles.3

References

- 1.Smith IM. A simple and fail safe method for digital tourniquet. J Hand Surg [Br] 2002;27:363–4. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2002.0781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durrant C. Forgotten digital tourniquet: salvage of an ischaemic finger by application of medicinal leeches. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:462–464. doi: 10.1308/003588406X117052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw JA. Guidelines for the use of digital touniquets based on physiological pressure measurements. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:1086–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The authors of the study have misinterpreted our clinical protocols and have failed to take into account the level of experience of the extended scope physiotherapist (ESP).

The authors quote that in back pain patients, one patient required investigation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). We find this figure surprisingly low. We have reviewed the same 64 back pain patients from records on our clinical database. Our results show that 17 patients (26.5%) required investigation with MRI.

Our own recalculation of data on the 150 patients, in accordance with the clinical protocols in place at the time of the study, found that 131 (87%) patients could be managed by an ESP and that twenty patients (13%) required a consultant surgeon review. The majority of patients requiring a consultant review had shoulder pathology. At the time of the audit, the ESP was still receiving training in the management of shoulder patients and was required for four months out of the six-month study period to review all patients with the surgical consultant as part of the training process.

The study highlights that the clinical protocols in our unit require the ESP to have regular access to discuss patients with the consultant surgeon, but the need for onward referral is low.

Footnotes

Comment on Pearse EO; Maclean A; Ricketts DM.. The extended scope physiotherapist in orthopaedic out-patients – an audit. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2006; 88: 653–655. doi: 10.1308/003588406X149183

We thank Messrs Smith and Patterson for their interest in our paper and commend their industry in reviewing the information they hold regarding the 64 cases with back pain on their database. Databases are not 100% accurate. The one used in this unit has been shown to have an overall completeness of 75% and an overall accuracy of 88%.1 We reviewed each and every patient record in order to obtain accurate data.

We identified 15 (23%) patients referred with back pain who had MRI scans. We collected data retrospectively and relied on documentation in the patients' medical records to determine whether cases were discussed with a consultant surgeon or not. A consultant in clinic reviewed three of these but two were listed for a procedure. To avoid duplication in Table 2, one patient was entered in the ‘MRI’ column and two in the ‘List for operation’ column. Of the remaining 12 cases that had MRI scans seven appeared to have been requested without discussion with the consultant surgeon in clinic but with follow-up arranged for the consultant to review the patient with the scans at a later date. A further two scans were requested at follow-up ESP clinic appointments without apparent discussion with the consultant surgeon in clinic but with follow-up arranged for the consultant to review the patients with the scans at a later date.

In one case a scan was requested by the surgical consultant after the patient was re-referred by their GP: the scan confirmed the clinical diagnosis made by the ESP and there was no change in the management of the patient, a point made in the ‘re-referral rate’ section of the results. There were two cases in which scans were requested without discussion with the consultant surgeon, and in which no follow-up was arranged with the consultant. The ESP followed these two patients up with the scans. We imagine that they discussed the results with the consultant at some stage but there was no clear documentation of this.

The ESPs themselves provided the written protocols that we relied upon. The department of physiotherapy produced these protocols. They clearly stated that a discussion with the surgical consultant was required before any request for radiological investigations could be made. Our review demonstrated an alternative arrangement had evolved where scans could be requested without formal review of the patient by a consultant surgeon at their first ESP clinic appointment. The cases were then reviewed at a later stage by the consultant.

A total of 17 cases were reviewed at a later date and not at the first ESP clinic appointment by a consultant surgeon. This gave a rate of independent initial assessment by ESPs of 66% but a rate of independent management by ESPs of 55%. Our standards favoured ESPs for the following reason. The paper by Hockin and Bannister reported 85% of patients could be managed independently but we set the standard (85%) for independent assessment of patients by an ESP. In our audit only 55% of highly selected patients were managed entirely independently by the ESPs. This may have significant implications for the delivery of the musculoskeletal services framework and the personnel mix of multidisciplinary clinical assessment and treatment services if they are to be effective.

We were not aware that the ESP received training in the management of shoulder patients for four out of the six-month study period. This would have been made clear in the paper if we had and we apologise for this oversight. It must be stressed that experience would not have changed the fact that 11 patients received injections, two were placed on the list for surgery and a further two patients required MRI scans. It is impossible to say how many of the remaining seven patients whom the consultant reviewed would or would not have required a consultant review with greater experience of the ESP.

Reference

- 1.Ricketts D. Markers of data quality in computer audit: the Manchester Orthopaedic Database. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1993 Nov;75:393–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

I enjoyed reading the article by MJ Hall et al. from Derriford Hospital. In my clinic we have been providing a copy of the GP letter to the patients for the last four years. At no time have I attempted to write a separate letter to the patient. I learnt fairly rapidly to strip out unnecessary medical terminology and to include summary statements about the main points of intended treatments, including their benefits and complications. As a result, an identical letter was sent to both patient and GP. Patients were informed that this would be the case and not one objected.

During that time I have received two complaints. One was from a patient with a ruptured aneurysm. A letter had been sent agreeing no further treatment would be undertaken and diamorphine should be given in the community in the event of rupture. This did not happen and the patient was admitted with severe pain to receive diamorphine. On the second occasion I described a patient with a significantly raised body mass index (BMI) as obese and his wife objected to this term and rang me to discuss it. It was clear that she took the view that this was a pejorative term, whereas I had used it in its descriptive sense. Subsequent to that date we have stated the BMI and had no further complaints.

Throughout the time that this process has been going on, there has been no increase in clinic time. There has been an increased use of paper and an increase in time taken to sign letters. Overall, the experience has proved positive, empowering the patients and enabling reiteration of important advice in writing.

Footnotes

Comment on Hall MJ; Edwards TJ; Ashley S; Walker AJ; Cosgrove C; Wilkins DC. The implications of providing patient-friendly letters in the outpatient clinic. Ann R Coll Surg Engl (Suppl) 2006; 88: 66–67. doi: 10.1308/147363507X169945

Thank you for the interesting letter in response to the article, The implications of providing patient-friendly letters in the outpatient clinic, published in the Bulletin in February. This highlights first hand how important it has become to involve patients fully in their care by supplying letters summarising their consultation as well as demonstrating that in clinical practice this protocol is now commonly employed.

I found it particularly interesting that Mr Mitchell has at no stage written a separate letter to patients and has simply modified the terminology in the GP letter in order that patients are able to understand the salient points. It would appear from Mr Mitchell's experience that this protocol works well within his clinical practice, with high rates of patient satisfaction in combination with maintaining an efficient use of clinic time by avoiding additional dictation of a separate letter.

The message from this response clearly reiterates the main message from our study, in that empowerment of patients by providing relevant clinical information in a form that is easily understood is now a crucial component in the delivery of an efficient professional health service.