Abstract

Botulinum neurotoxins cause botulism, a neuroparalytic disease in humans and animals. We constructed a replication-incompetent adenovirus encoding a synthesized codon-optimized gene for expression of the heavy chain C-fragment (HC50) of botulinum neurotoxin type C (BoNT/C). This recombinant human serotype 5 adenoviral vector (Ad5) was evaluated as a genetic vaccine candidate against botulism caused by BoNT/C in a mouse model. A one-time intramuscular injection with 105 to 2 × 107 pfu of adenoviral vectors elicited robust serum antibody responses against HC50 of BoNT/C as assessed by ELISA. Immune sera showed high potency in neutralizing the active BoNT/C in vitro. After a single dose of 2 × 107 pfu adenoviral vectors, the animals were completely protected against intraperitoneal challenge with 100 × MLD50 of active BoNT/C. The protective immunity appeared to be vaccine dose-dependent. The anti-toxin protective immunity could last for at least 7 months without a booster injection. In addition, we observed that pre-existing immunity to the wild type Ad5 in the host had no significant influence on the protective efficacy of vaccination. The data suggest that an adenovirus-vectored genetic vaccine is a highly efficient prophylaxis candidate against botulism.

Keywords: Botulism Vaccine, Protective immunity, Replication-incompetent adenovirus

1. Introduction

Botulism is a life-threatening neuroparalytic disease caused by botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs), which are produced by one of the seven structurally similar Clostridium botulinum serotypes, designated A to G in which type C has two subtypes (C1 and C2). In addition, Clostridium baratii synthesizes only serotype F and Clostridium butyricum synthesizes only serotype E. As the concept of serotype implies, each of the toxins is immunologically distinct. The only exception to this general rule is serotypes C and D, which share significant cross-homology [1]. BoNTs are the most poisonous substances known in nature. They may be used as bioterrorism agents or in biological warfare [2]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for the development of effective vaccines to protect against botulism.

Currently, a pentavalent botulinum toxoid vaccine that may protect against BoNT serotypes A–E is available as an Investigational New Drugs (IND) [3, 4]. However, there are shortcomings with the toxoid vaccines. For example, the cost of manufacturing is very high, because C. botulinum is a spore-former and a dedicated cGMP facility is required to manufacture a toxin-based product. The yields of toxin production from C. botulinum are relatively low; it is dangerous to produce them, as the toxoiding process involves handling large quantities of toxin, and the added safety precautions increase the cost of manufacturing. The toxoid product for types A–E consists of a crude extract of clostridial proteins that may influence immunogenicity or reactivity of the vaccine, but the type F toxoid is only partially purified; residual formaldehyde (not to exceed 0.02%) and the preservative thimerosal (0.01%), are part of final product formulation. This increases the reactogenicity of the vaccine [5].

A high sequence and structural homology exists between the clostridial neurotoxins produced by Clostridium tetani and C. botulinum. The successful demonstration that C-fragment of tetanus toxin (TeNT) elicits protective immunity in animals has prompted the development of a new subunit vaccine against botulism [6, 7]. Evaluation of the immunogenicity of different regions of BoNTs has confirmed that the C-fragment of the BoNTs elicits protective immunity in animals [8–13]. Therefore, subsequent efforts to develop vaccine candidates to protect against BoNTs forthwith may focus on the HC region of BoNTs [14]. Because the C-domains of the BoNTs are responsible for receptor binding, host immune response against these domains may prevent the BoNTs from gaining access into target cells. Research on peptide-based vaccines has shown several synthetic peptides elicit antibody and T-cell responses in two different strains of mice (BALB/c and SJL) that cross-react with the HC region of BoNT/A. These experiments show the feasibility of developing a synthetic vaccine that could protect against botulinum neurotoxin intoxication [5, 15–18]. The employment of the non-toxic fragments of BoNTs as protective antigens also provides a significant safety profile advantage.

Replication-incompetent adenoviruses are currently available efficient gene transfer vehicles for both in vitro and in vivo approaches [19, 20]. Adenovirus-vectored recombinant vaccines expressing a wide array of antigens have been constructed and protective immunity against different pathogens has been demonstrated in animal models [21–25]. In our research, we demonstrated the efficacy of using an adenovirus-based vaccine for single-time genetic vaccination that provided long-lasting protective immunity against botulism caused by botulinum neurotoxin type C.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Construction of adenoviral vector encoding codon-optimized HC50 of BoNT/C

Replication-incompetent recombinant adenoviral vectors were constructed using the AdEasy™ System (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) [26, 27]. The adenoviral vector is derived from human adenovirus serotype 5 rendered replication-incompetent by the deletion of the E1 and E3 regions. To construct the Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50, the nucleotides encoding the 50-kDa C-terminal fragment of heavy chain of botulinum neurotoxin type C1 [28] was optimized with human codon preference by the DNAworks program [29]. The nucleotides encoding the signal peptide of human tissue plasminogen activator (PLAT) (amino acids 1–25, GenBank Acc# BC002795) plus 2 serines followed with the codon-optimized BoNT/C-HC50 (encoding amino acids 849-1291 in BoNT/C, GenBank Acc# D90210) were then synthesized by a PCR-based method [30]. The synthesized DNA was subsequently cloned into a shuttle vector pShuttle-CMV (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) at its SalI site. The DNA sequence of the synthesized gene was further confirmed by DNA sequencing analysis. The new opt-BoNT/C-HC50 sequence will be assigned an access number #X (pending submission) in the GenBank. Table 1 shows the native and codon-optimized opt-BoNT/C-HC50 sequences. The adenoviral vector was then constructed according to the standard procedures as described previously [26, 27]. In the adenovirus, the transgene expression is under control of human cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate early promoter/enhancer and then followed with a simian virus 40 (SV40) stop/polyadenylation signal [26]. Similarly, the Ad/Null vector without transgene was also constructed. Adenoviruses isolated from single plaques were then produced in AD293 cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and purified by CsCl gradient purification and dialyzed with adenovirus storage buffer containing 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 135 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2. The purified adenoviruses were stored in 1.0 M sucrose in a −80°C freezer until use and their titers (pfu) were determined by plaque assay before vaccinating animals.

Table 1.

Comparison of native and codon-optimized BoNT/C-HC50 DNA and protein sequences

| Position | Sequence | |

|---|---|---|

| Native | 1 | GATATAATTAATGAATATTTCAATAATATTAATGATTCAAAAATTTTGAGCCTACAAAACAGAAAAAATACTTTAGTGGATACATCAGGATATAATGCA |

| Optimized | 1 | GACATTATCAACGAGTACTTCAATAACATCAATGACAGCAAGATCCTGTCCCTGCAAAATCGGAAAAACACTCTGGTGGACACCAGCGGATATAACGCT |

| Protein | 1 | D I I N E Y F N N I N D S K I L S L Q N R K N T L V D T S G Y N A |

| Native | 100 | GAAGTGAGTGAAGAAGGCGATGTTCAGCTTAATCCAATATTTCCATTTGACTTTAAATTAGGTAGTTCAGGGGAGGATAGAGGTAAAGTTATAGTAACC |

| Optimized | 100 | GAGGTGAGCGAAGAAGGCGATGTGCAACTGAACCCAATCTTCCCCTTTGATTTTAAGCTGGGCTCCTCCGGCGAGGATAGGGGGAAAGTCATCGTCACC |

| Protein | 34 | E V S E E G D V Q L N P I F P F D F K L G S S G E D R G K V I V T |

| Native | 199 | CAGAATGAAAATATTGTATATAATTCTATGTATGAAAGTTTTAGCATTAGTTTTTGGATTAGAATAAATAAATGGGTAAGTAATTTACCTGGATATACT |

| Optimized | 199 | CAGAATGAAAACATCGTCTACAATAGCATGTACGAGAGCTTCAGCATCTCCTTCTGGATCAGAATTAACAAATGGGTCAGCAACCTGCCAGGATATACC |

| Protein | 67 | Q N E N I V Y N S M Y E S F S I S F W I R I N K W V S N L P G Y T |

| Native | 298 | ATAATTGATAGTGTTAAAAATAACTCAGGTTGGAGTATAGGTATTATTAGTAATTTTTTAGTATTTACTTTAAAACAAAATGAAGATAGTGAACAAAGT |

| Optimized | 298 | ATCATCGACAGCGTGAAGAACAACTCCGGGTGGTCCATCGGGATTATCTCCAATTTTCTGGTGTTCACTCTGAAACAAAACGAAGATAGCGAACAGAGC |

| Protein | 100 | I I D S V K N N S G W S I G I I S N F L V F T L K Q N E D S E Q S |

| Native | 397 | ATAAATTTTAGTTATGATATATCAAATAATGCTCCTGGATACAATAAATGGTTTTTTGTAACTGTTACTAACAATATGATGGGAAATATGAAGATTTAT |

| Optimized | 397 | ATCAATTTCTCCTACGACATTTCCAACAATGCACCAGGGTATAACAAGTGGTTCTTTGTCACTGTCACCAACAACATGATGGGGAACATGAAGATTTAC |

| Protein | 133 | I N F S Y D I S N N A P G Y N K W F F V T V T N N M M G N M K I Y |

| Native | 496 | ATAAATGGAAAATTAATAGATACTATAAAAGTTAAAGAACTAACTGGAATTAATTTTAGCAAAACTATAACATTTGAAATAAATAAAATTCCAGATACC |

| Optimized | 496 | ATCAACGGAAAACTGATTGATACTATTAAGGTCAAGGAACTCACCGGCATTAACTTCTCCAAGACAATTACATTTGAGATCAATAAGATTCCAGACACC |

| Protein | 166 | I N G K L I D T I K V K E L T G I N F S K T I T F E I N K I P D T |

| Native | 595 | GGTTTGATTACTTCAGATTCTGATAACATCAATATGTGGATAAGAGATTTTTATATATTTGCTAAAGAATTAGATGGTAAAGATATTAATATATTATTT |

| Optimized | 595 | GGACTCATTACTAGCGACTCCGACAATATCAATATGTGGATTAGGGACTTCTACATCTTTGCTAAAGAACTGGATGGCAAGGATATTAACATTCTCTTC |

| Protein | 199 | G L I T S D S D N I N M W I R D F Y I F A K E L D G K D I N I L F |

| Native | 694 | AATAGCTTGCAATATACTAATGTTGTAAAAGATTATTGGGGAAATGATTTAAGATATAATAAAGAATATTATATGGTTAATATAGATTATTTAAATAGA |

| Optimized | 694 | AACTCCCTCCAATACACAAACGTCGTCAAAGACTATTGGGGCAACGACCTGAGATACAACAAAGAGTATTACATGGTCAACATCGATTACCTGAACAGA |

| Protein | 232 | N S L Q Y T N V V K D Y W G N D L R Y N K E Y Y M V N I D Y L N R |

| Native | 793 | TATATGTATGCGAACTCACGACAAATTGTTTTTAATACACGTAGAAATAATAATGACTTCAATGAAGGATATAAAATTATAATAAAAAGAATCAGAGGA |

| Optimized | 793 | TATATGTACGCCAACAGCAGGCAAATTGTGTTCAACACACGGAGGAATAACAATGATTTCAACGAAGGCTATAAGATCATCATCAAAAGAATCAGGGGA |

| Protein | 265 | Y M Y A N S R Q I V F N T R R N N N D F N E G Y K I I I K R I R G |

| Native | 892 | AATACAAATGATACTAGAGTACGAGGAGGAGATATTTTATATTTTGATATGACAATTAATAACAAAGCATATAATTTGTTTATGAAGAATGAAACTATG |

| Optimized | 892 | AACACTAATGACACTAGGGTCAGAGGCGGCGACATTCTGTATTTTGACATGACTATCAACAATAAGGCCTACAACCTGTTTATGAAAAACGAGACAATG |

| Protein | 298 | N T N D T R V R G G D I L Y F D M T I N N K A Y N L F M K N E T M |

| Native | 991 | TATGCAGATAATCATAGTACTGAAGATATATATGCTATAGGTTTAAGAGAACAAACAAAGGATATAAATGATAATATTATATTTCAAATACAACCAATG |

| Optimized | 991 | TATGCTGATAACCACAGCACAGAAGATATTTACGCAATCGGCCTGAGGGAGCAAACCAAAGACATTAACGATAATATCATTTTCCAGATCCAGCCAATG |

| Protein | 331 | Y A D N H S T E D I Y A I G L R E Q T K D I N D N I I F Q I Q P M |

| Native | 1090 | AATAATACTTATTATTACGCATCTCAAATATTTAAATCAAATTTTAATGGAGAAAATATTTCTGGAATATGTTCAATAGGTACTTATCGTTTTAGACTT |

| Optimized | 1090 | AATAATACCTACTACTACGCAAGCCAAATTTTCAAGAGCAACTTTAACGGAGAGAACATCAGCGGAATCTGCAGCATTGGGACCTACAGGTTTAGACTC |

| Protein | 364 | N N T Y Y Y A S Q I F K S N F N G E N I S G I C S I G T Y R F R L |

| Native | 1189 | GGAGGTGATTGGTATAGACACAATTATTTGGTGCCTACTGTGAAGCAAGGAAATTATGCTTCATTATTAGAATCAACATCAACTCATTGGGGTTTTGTA |

| Optimized | 1189 | GGGGGAGACTGGTATAGACATAATTACCTCGTGCCTACCGTCAAGCAGGGAAATTATGCCAGCCTCCTCGAAAGCACTTCCACCCATTGGGGATTTGTC |

| Protein | 397 | G G D W Y R H N Y L V P T V K Q G N Y A S L L E S T S T H W G F V |

| Native | 1288 | CCTGTAAGTGAA |

| Optimized | 1288 | CCCGTCTCCGAGTGA |

| Protein | 430 | P V S E * |

2.2. Animal vaccination and sample collection

Six to eight-week old, female Balb/c mice, were purchased from Taconic Farms (Hudson, NY), and housed in the animal facility of University of Rochester (4 animals per cage). They were maintained in a controlled environment (22 ± 2°C; 12 h light/12 h dark cycles) in accordance with the U.S. Public Health Service “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.” The animals were provided Laboratory Rodent Diet 5001 with ad libitum access to food and water. The research was conducted in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and other federal and state statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals and adheres to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, NRC Publication, 1996 edition.

Experiment 1

Mice were allotted into 5 groups (8 mice/group). They were injected i.m. into the hind-leg quadriceps with different doses of Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 vector (105, 106, or 2 × 107 pfu/mouse), Ad/Null (2 × 107 pfu/mouse), and the Botulinum Toxoid Adsorbed Pentavalent (ABCDE) (0.05 ml/mouse), an IND vaccine which was produced by the Michigan Department of Public Health. Animals were inoculated once in week 0. Animal sera were obtained by retro-orbital bleeding every 2 weeks (in week 0, 2, 4, and 6) and stored at −20°C until further assays. Vaccinated mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) challenged with 100 × MLD50 BoNT/C 1 week after last bleeding described in the following section.

Experiment 2

To determine long-term protective immunity, mice were allotted into another 3 experimental groups (8 mice/group) and 3 control groups (4 mice/group). Animals were intramuscularly (i.m.) vaccinated with Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 vector (2 × 107 pfu/mouse) in experimental groups and with Ad/Null (2 × 107 pfu/mouse) in control groups in week 0. Animal sera were obtained by retro-orbital bleeding in weeks 0, 10, 18, and 26. One experiment and one control group were challenged i.p. with 100 × MLD50 BoNT/C in weeks 11, 19, and 27.

Experiment 3

To investigate the effect of pre-existing immunity to adenovirus on the vaccination efficacy, 12 mice were allotted into one experiment (8 mice/group) and one control group (4 mice/group). Animals were intranasally (i.n.) inoculated with wide-type human adenovirus serotype 5 (2 × 107 pfu/mouse) (ATCC, VA) in week 0 and bled in week 4. They were subsequently inoculated with Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 vector (2 × 107 pfu/mouse) in the experimental group or with Ad/Null (2 × 107 pfu/mouse) in the control group in week 4 and challenged i.p. with 100 × MLD50 BoNT/C in week 11.

2.3. Challenge with botulinum neurotoxin in mice

All animals were challenged by i.p injection with 100 × MLD50 botulinum neurotoxin type C (Metabiolgics Inc, Madison, WI) at the time indicated in each experiment. The challenged animals were monitored for 7 days. They were observed every 4 h for the first two days and twice a day thereafter. The number of deaths for each group was recorded as the endpoint [31].

2.4. ELISA for determination of antibody concentration

Serum anti- BoNT/C-HC50 IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a antibody concentrations were determined using an ELISA Quantization kit (Bethel Lab. Inc., Montgomery TX) with a modified procedure. Briefly, 96-well flat-bottom immuno plates (Nagle Nunc International, Rochester, NY) were coated with 0.5 μg/well of either His-tagged BoNT/C-HC50 recombinant protein produced in Escherichia coli or capture antibodies (goat anti-mouse IgG-, or IgG1-, or IgG2a -affinity purified, Bethel Lab, Montgomery, TX, for standard curve) in 100 μl coating buffer (0.05M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6) at 4°C overnight. The plates were washed 5 times with washing buffer (0.05% Tween 20 in PBS) and nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 200 μl PBS (pH 7.4) containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at room temperature. After five washes, 100-μl serial dilutions of reference serum containing given amounts of mouse antibodies (for standard curve) or 1:100 dilutions of mouse serum samples in PBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 1% BSA were added. After 2 h further incubation at 37°C, the plates were washed with washing buffer 5 times and incubated with 100 μl/well of 1:10,000 dilution of goat anti-mouse IgG, IgG1 or IgG2a conjugated to alkaline phosphatase for 1 h at room temperature. Unbound antibodies were removed by washing 5 times with washing buffer, and the bound antibody was detected after incubation with p-nitrophenylphosphate phosphatase substrate system (KPL, Gaithersburg, Maryland) for 30 min. The color reaction was terminated by adding 100 μl 0.5 M EDTA and the absorbance values were obtained using a Dynatech MR4000 model microplate reader at 405 nm. A standard curve was generated for each set of samples and serum antibody concentrations were calculated in accordance with a standard curve as previously described [32].

2.5. Botulinum neurotoxin neutralization assay

Neutralizing antibody titers to BoNT/C were measured by the ability of sera to neutralize the neurotoxin in vitro in combination with the mouse lethality assay. 200 μl of pooled sera from 8 mice 6 weeks after vaccination with 2 × 107 pfu of Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 vector or with Ad/Null were initially diluted 1:4 and then diluted in twofold series (1:4 to 1:1052) in DPBS (Dulbecco’s PBS). 400 × MLD50 BoNT/C in 200 μl of DPBS was added into each dilution. After incubation at room temperature for 1 h, the anti-serum and the BoNT/C mixture was injected i.p. into mice, 100 μl (corresponding to 100 × MLD50 of BoNT/C before neutralization) per mouse, 4 mice were tested for each dilution. The mice were monitored for 4 days, and the number of deaths at each sample dilution was recorded. If the toxin was neutralized, the mice were protected from the challenge with neutralized toxin. The detection limit for this assay was 0.04 IU/ml due to the limited amount of serum available. Neutralizing antibody titers were defined as the maximum number of IU of antitoxin per ml of serum, resulting in 100% survival after challenge. One IU of botulinum neurotoxin antitoxin neurotoxin neutralized 10,000 × MLD50 [33].

2.6. Anti-adenovirus neutralizing antibody titer assay

Anti-adenovirus neutralizing antibodies were determined according to previously described methods with some modifications [34–36]. Briefly, AD293 cells (Stratagene, CA) were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 104 cells/well in 200 μl of Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM) containing 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 50 U of penicillin per ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin per ml and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 overnight. Mouse serum samples were heat-inactivated at 55°C for 45 min and then serially twofold diluted in MEME containing 2% FBS in a new 96-well culture plate. Approximately 104 pfu of wild-type human adenovirus Ad5 in 50 μl of MEME containing 2% FBS was mixed with 50 μl of diluted serum samples. After incubation for 1 h at 37°C to allow neutralization to occur, 100 μl of virus-serum mixture was subsequently added to AD293 cells, and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After incubation, the virus-serum medium was replaced with 200 μl of EMEM containing 10% FBS. The cells were incubated at 37°C until the negative wells exhibited 90% cytopathic effect. The neutralizing antibody titer was determined to be the highest dilution wells showing <50% cytopathic effect as previously described [34–36].

2.7. Statistical analysis

Serum antibody concentration titers among different groups at different time points were compared and analyzed using the LSD test and ANOVA/MANOVA with STATISTICA 7.1 software (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK); in comparing groups, those with P-values < 0.05 and < 0.01 were considered to be significant and very significant, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Antibody response to HC50 of BoNT/C after vaccination

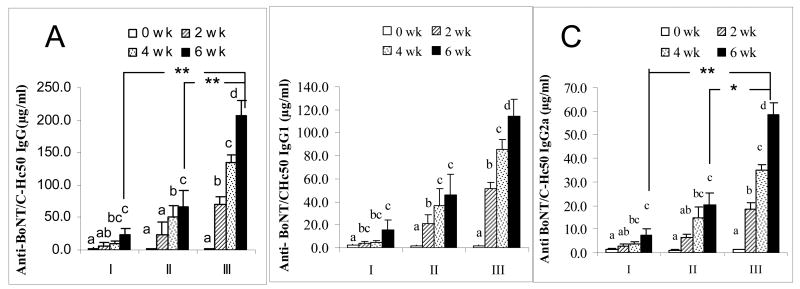

Groups (8 mice/group) of female Balb/c mice were inoculated intramuscularly (i.m.) with recombinant adenovirus Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50. After a single dose of 105, 106, 2 × 107 plaque-formation units (pfu) of Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 vector in week 0, antibody responses in animal sera were measured by quantitative ELISA. Fig. 1 shows BoNT/C-HC50-specific antibody responses in sera 2, 4, and 6 weeks after vaccination. The data indicate that the lowest vaccine dosage 105 pfu tested was sufficient to elicit significant IgG1 and IgG2a antibody responses in Week 6 compared with the control group injected with Ad/Null (an Ad5 vector with no transgene) (P values < 0.05). The rise in antigen-specific IgG1 (Fig. 1B) and IgG2a (Fig. 1C) after vaccination suggested that both Th2 and Th1 immune responses were elicited. More specifically, the IgG antibody response could be characterized as a predominant Th2 response (values of IgG2a/IgG1 < 1.0). In addition, serum antibody responses were clearly vaccine-dose dependent.

Fig. 1.

Anti HC50 of BoNT/C response in vaccinated mice. Mice were inoculated with different doses of Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 in week 0. Serum samples were obtained at weeks 0, 2, 4, and 6. Anti-BoNT/C-HC50 IgG (Panel A), IgG1(Panel B) and IgG2a (Panel C) antibody concentrations were measured by a quantitative ELISA kit (Bethyl, Montgomery, TX). Virus doses for groups I, II, and III were 105, 106, and 2 × 107 pfu, respectively. Mean = X ± SE (n = 8). Values without the same letters (a, b, c, d) differ significantly in the same dosage groups (P < 0.05). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

3.2. In vitro neutralization of botulinum neurotoxin

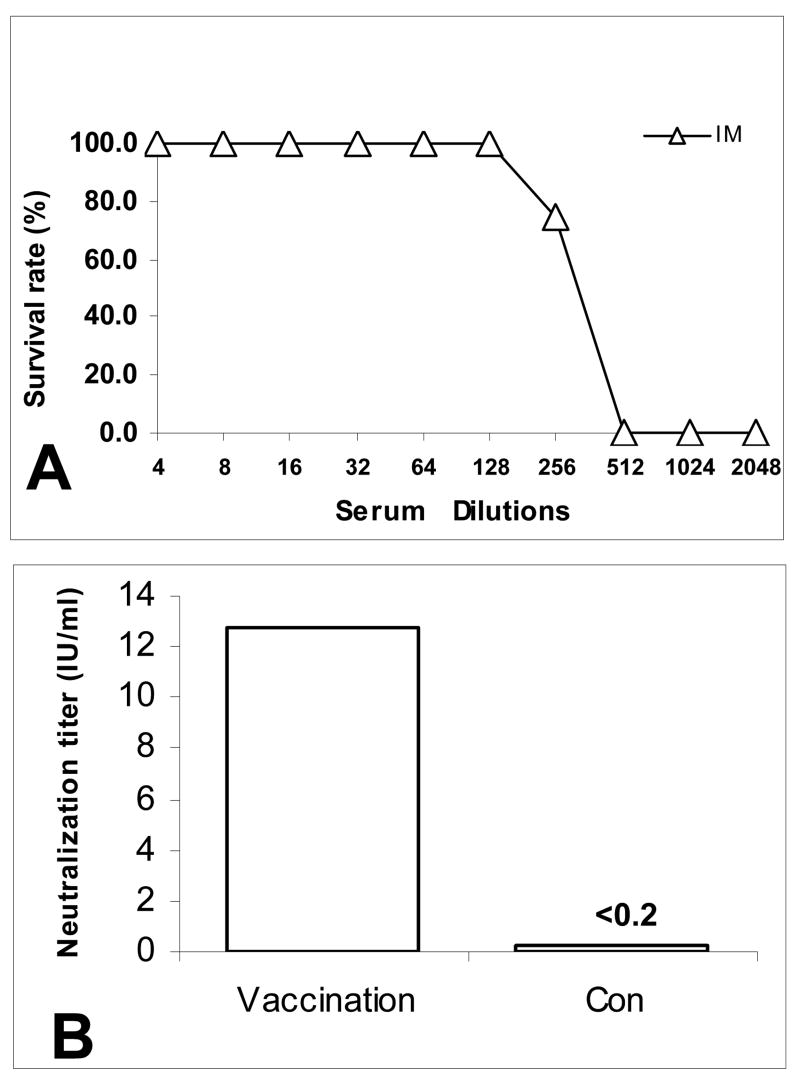

In order to determine whether anti-HC50 antibodies in the sera were capable of neutralizing active BoNT/C, an in vitro neurotoxin neutralization combined with the mouse lethality assay (MLA) were performed. Pooled sera from vaccinated animals were used for in vitro toxin neutralization. As shown in Fig. 2A, up to 128-fold diluted sera from animals 6 weeks after a single injection of 2 × 107 pfu of Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 completely neutralized 100 × MLD50 BoNT/C under experimental conditions and resulted in a 100% survival rate after administration of the neutralized toxin in mice. This translated to a 13 IU/ml anti-BoNT/C neutralization titer (Fig. 2B). These data suggested that parental inoculation with the adenoviral vector could elicit functional antibody responses that neutralized active botulinum neurotoxin.

Fig. 2.

Serum anti-BoNT/C neutralizing antibody titer assay. 50 μl of serum from each mouse in the same group were pooled 6 weeks after vaccination with Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 (8 mice/group). Sera were 1:4 diluted initially with Dulbecco’s PBS and then in twofold series for determination of anti-BoNT/C neutralization titers. Panel A: mice survival rates after challenge with neutralized BoNT/C; Panel B: serum anti-BoNT/C neutralization titers (IU/ml, one IU is equal to 10,000 × MLD50). IM: vaccination (n = 4).

3.3. Protective immunity elicited by the adenovirus-vectored vaccine

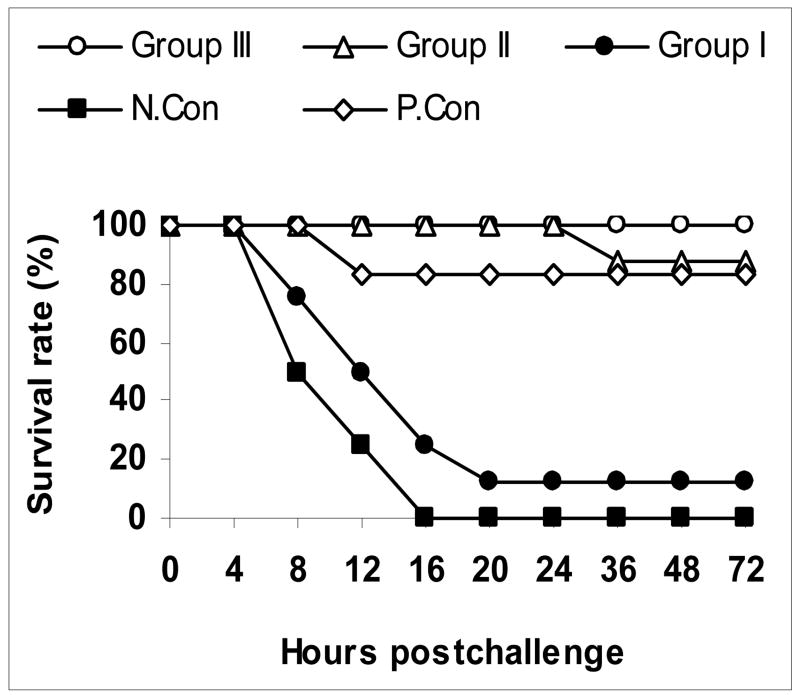

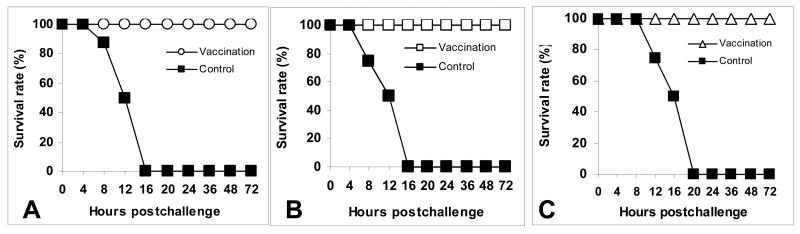

To explore whether the HC50-based adenovirus-vectored vaccine protect against botulinum neurotoxin intoxication, the vaccinated mice were intraperitoneally challenged (i.p.) with 100 50% mouse lethal dose (MLD50) units of active BoNT/C 7 weeks after injection. The results from the challenge experiments showed that vaccination with 105 pfu of Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 could protect 12.5 % of the animals against the toxin challenge (Fig. 3). However, the protection rates rose to 75% and 100% when the vaccine dose was increased to 106 and 2 × 107 pfu, respectively. This suggested that vaccine dose-dependent protective immunity was achieved after vaccination.

Fig. 3.

Protection against active BoNT/C in mice vaccinated with adenoviral vector. Mice were vaccinated with different dosages of adenovirus-vectored vaccine Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 in week 0 and then challenged in week 7 with 100 × MLD50 BoNT/C. Ad/opt-BONT/C-HC50-vaccinated groups: I, 105 pfu; II, 106 pfu; III, 2 × 107 pfu; N.Con: negative control was inoculated with 2 × 107 pfu of Ad/Null; P.Con: positive control group was vaccinated i.m. with 50 μl of the pentavalent (ABCDE) botulinum toxoid vaccine.

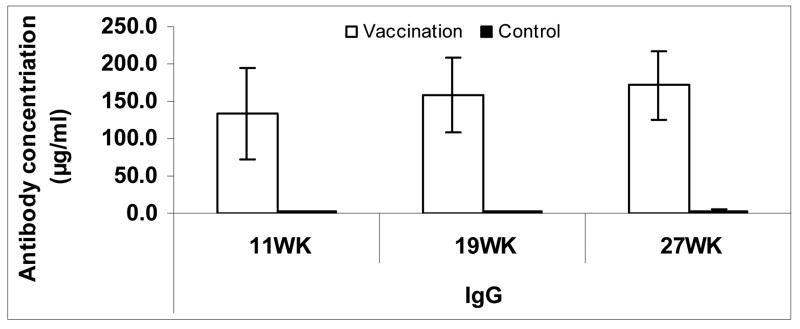

In order to determine if a single dose of Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 could provide long-term immunity against botulinum neurotoxin, another 6 groups of mice were inoculated with 2 × 107 pfu of Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 or with control vector Ad/Null. Serum samples were collected in weeks 0, 11, 19, and 27. As shown in Fig. 4, BoNT/C-HC50-specific antibody titers in sera were sustained until at least 27 weeks after vaccination (p < 0.05). To evaluate protective immunity at different time points, the vaccinated animals were subsequently challenged with 100 × MLD50 of active BoNT/C in week 11, 19, and 27. As indicated in Fig. 5, a single dose of Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 administered i.m. completely protected animals against botulism at all time points examined. This suggests the long-lasting memory immunity against botulinum neurotoxin was elicited after a single dose of the adenovirus-vectored vaccine.

Fig. 4.

Sustaining of antigen specific antibody responses after vaccination with the adenovirus-vectored vaccine in mice. Mice were inoculated i.m. with a single dose of 2 × 107 pfu of Ad/opt-BONT/C-HC50 (vaccination) or with Ad/Null (control) in week 0. Serum samples were obtained in weeks 11, 19, and 27 before challenging with BoNT/C. The anti-BoNT/C-HC50 IgG antibody concentrations in sera were determined using a quantitative ELISA kit (Bethyl, Montgomery, TX). Mean=X ± SD (n = 7 or 8 in vaccination groups and n = 4 in control groups).

Fig. 5.

Long-lasting protective immunity in vaccinated mice against BoNT/C challenge. Mice were injected i.m. with 2 × 107 pfu of Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 or with Ad/Null in week 0 and then challenged with 100 × MLD50 BoNT/C in week 11 (Panel a), week 19 (Panel b) and week 27 (Panel c). n = 8 in experiment groups; n = 4 in control groups.

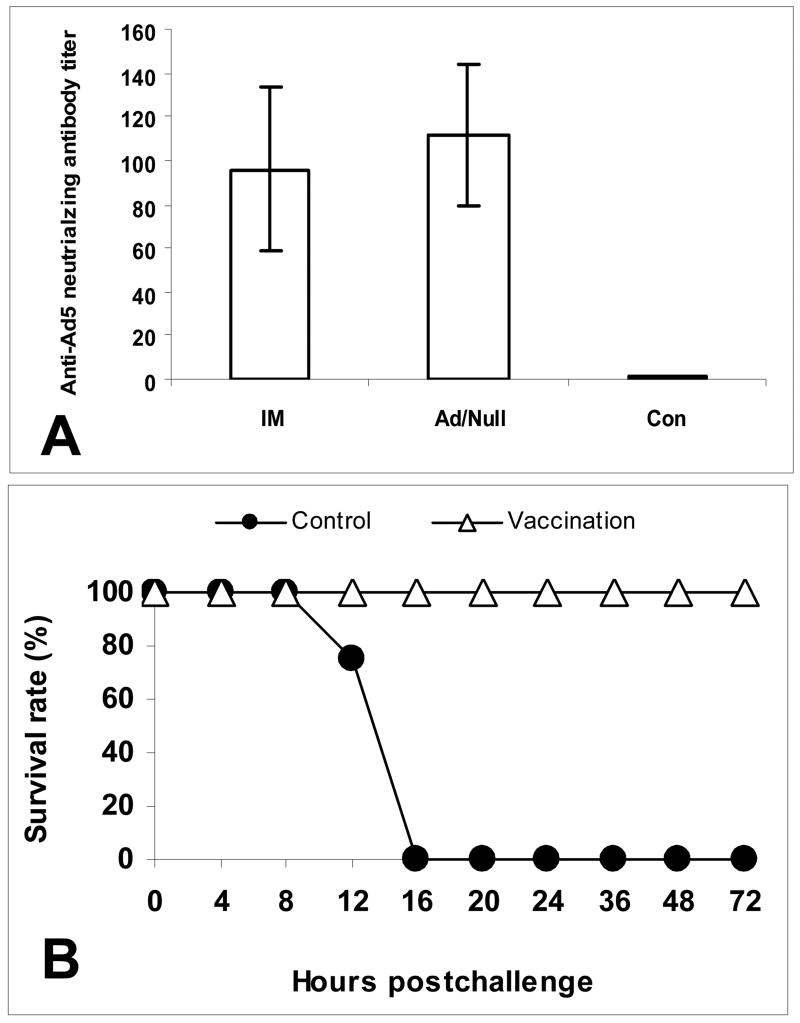

3.4. Influence of pre-existing anti-adenovirus immunity on the efficacy of vaccination

To investigate if host pre-existing immunity to the adenoviral vector could limit the efficacy of the vaccination with this adenovirus-based vaccine, we performed an additional experiment. Mice were first inoculated intranasally (i.n.) with 2 × 107 pfu of wild-type 5 human adenovirus (WT Ad5). Serum-neutralizing antibody titers against WT Ad5 were assessed by a 96-well neutralization antibody assay. The results showed all animals had anti-adenovirus neutralizing antibody responses, with average viral neutralization titers ranging from 96 to 112 (Fig. 6A) 4 weeks after inoculation of WT Ad5. The animals with pre-existing immunity to adenovirus were subsequently inoculated i.m. with a single dose of 2 × 107 pfu of Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 or with control vector Ad/Null in week 4 and challenged i.p. with 100 × MLD50 of active BoNT/C in week 11. The results in Fig. 6B show that all animals inoculated with Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 survived the toxin challenge and none of the control mice were protected. These data suggest that pre-existing immunity to adenovirus in the host did not affect the protective efficacy of the vaccination with this adenovirus-based botulism vaccine.

Fig. 6.

Effect of pre-existing immunity to adenovirus on the efficacy of the adenovirus-vectored vaccine. Panel A: Anti-adenovirus neutralizing antibodies in animals inoculated with adenovirus pre-vaccination. Mice were inoculated i.n. with 2 × 107 pfu/mouse of wild-type human adenovirus serotype 5 in week 0. Serum samples were obtained in week 4 and the anti-Ad5 neutralizing antibody titers were subsequently measured. Mean = X ± SE. IM group: the group that was subsequently vaccinated with Ad/opt-BONT/C-HC50 in Panel B; Ad/Null: the group that was subsequently injected with Ad/Null in Panel B; Con: data were obtained from mouse sera before inoculation of WT Ad5. Panel B: Protective immunity. Each mouse was inoculated i.n. with 2 × 107 pfu of WT Ad5 in week 0 as shown in Panel A, then subsequently injected with 2 × 107 pfu Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 in vaccination group or with Ad/Null in control group in week 4, and challenged with 100 × MLD50 BoNT/C in week 11. (n = 8 in vaccination groups; n = 4 in control groups)

4. Discussion

The genetic vaccination strategy was previously attempted in botulism vaccine development. Clayton and Middlebrook constructed a plasmid DNA encoding the nontoxic HC50 region of BoNT/A and showed it to partially protect against toxin challenge after up to 4 booster injections [37]. Jathoul et al. constructed plasmid DNA expressing BoNT/F HC under the control of human ubiquitin gene (UbC) promoter and found that two i.m. injections afforded 90% protection against BoNT/F challenge [38]. In addition, Lee and coworkers introduced the HC50 of BoNT/A or BoNT/C into the Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) virus replicon vector. These constructs not only yielded high levels of HC fragments, as judged by immunofluorescence and immunoblotting analysis, but also protected mice against BoNT/A or BoNT/C challenge after 2 or 3 injections with 107 infectious units (i.u.) of VEE [39–41]. However, a single dose of genetic vaccine was not fully protective against botulism in these studies.

In our research, we demonstrated that it is possible to develop a highly efficient genetic vaccine against botulism using an adenoviral vector encoding the HC50 fragment of BoNT/C. In the recombinant adenovirus we constructed, the DNA sequence encoding the HC50 fragment antigen was codon-optimized with human codon preference. This resulted in high-level expression of HC50. It might be secreted from host cells using the signal peptide of human tissue plasminogen activator (PLAT) [42, 43], and the secretory HC50 might be presented to antigen-presenting cells (APCs) more efficiently after vaccination. In any case, the vaccine construct was more potent at inducing host immune responses than was an adenoviral vector encoding the native HC50 sequence (data not shown).

A single i.m. dose of the Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 was capable of eliciting significant Th2 and Th1 immune responses against HC50 fragment of BoNT/C (Fig. 1) and the serum antigen-specific antibodies were capable of neutralizing active BoNT/C (Fig. 2). The protective antibodies against HC50 of BoNT/C were sustained for long-term (up to 27 weeks) (Fig. 4). Host immune responses and protective immunity appeared to be vaccine dose-dependent. Most importantly, a single dose of 2 × 107 pfu of Ad/opt-BoNT/C-HC50 was sufficient to provide long-term protective immunity (Fig. 5). This study is the first to demonstrate that a single genetic vaccination is able to provide long-lasting protection against botulism.

Because we used the human Ad5-derived replication-incompetent adenovirus for vaccine delivery, the issue of host pre-existing immunity against adenoviruses needed to be addressed. The data from our experiments showed that even with pre-existing anti-adenovirus neutralizing antibody in the host, the protective efficacy of the vaccination was sustained (Fig. 6). However, this result may need to be interpreted with caution as the ability for replication of human adenovirus is limited in murine cells [44], and human immune response to adenovirus may differ from that of mouse.

Another important issue in using adenoviruses as vaccines is to maintain the adenoviral vectors non-infective in the host. There is possible contamination of replication-competent adenovirus (RCA) in the vaccines using currently available HEK293 cells for adenovirus propagation. The 293 cells are human embryonic kidney cells originally transformed with the right arm of adenovirus serotype 5. When the E1/E3 defective adenovirus is produced with this cell line, it is possible that the vector could acquire an E1 gene from the cellular genome by homologous recombination to generate RCA. To avoid RCA occurrence, new suitable packaging cell lines such as the Per.C6 and UR cell lines were developed recently [45–47], and these cell lines could be worthwhile if a clinical trial were to be pursued.

In summary, our research demonstrated for the first time that an adenovirus-based vector encoding a humanized HC 50-kDa fragment of BoNT/C was capable of eliciting robust host immunity against botulism caused by BoNT/C after a single dose. The anti-BoNT/C protective immunity was sustained for a prolonged time period. This strategy could be used to further develop a multivalent vaccine against all serotypes of botulinum neurotoxins.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Public Service research grant AI055946 (M. Z.) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. M. E and L. L. S were supported by National Institutes of Health contract NO1-AI30028, grant NS022153, and GM57345. The authors thank Eric D. Hesek for constructing and purifying the adenoviral vectors. We are grateful to Alexandra Kravitt for performing several ELISA experiments. We also acknowledge the support from Barbara H. Iglewski, De-chu C. Tang, Stephen Dewhurst, and Robert C. Rose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Oguma K, Syuto B, Iida H, Kubo S. Antigenic similarity of toxins produced by Clostridium botulinum type C and D strains. Infect Immun. 1980;30(3):656–60. doi: 10.1128/iai.30.3.656-660.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnon SS, Schechter R, Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, et al. Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. Jama. 2001;285(8):1059–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.8.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright GG, Duff JT, Fiock MA, Devlin HB, Soderstrom RL. Studies on immunity to toxins of Clostridium botulinum. V. Detoxification of purified type A and type B toxins, and the antigenicity of univalent and bivalent aluminium phosphate adsorbed toxoids. J Immunol. 1960;84:384–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiock MA, Cardella MA, Gearinger NF. Studies on Immunity to Toxins of Clostridium Botulinum. Ix. Immunologic Response of Man to Purified Pentavalent Abcde Botulinum. Toxiod J Immunol. 1963;90:697–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrne MP, Smith LA. Development of vaccines for prevention of botulism. Biochimie. 2000;82(9–10):955–66. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)01173-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helting TB, Nau HH. Analysis of the immune response to papain digestion products of tetanus toxin. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand [C] 1984;92(1):59–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1984.tb00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fairweather NF, Lyness VA, Maskell DJ. Immunization of mice against tetanus with fragments of tetanus toxin synthesized in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1987;55(11):2541–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.11.2541-2545.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaPenotiere HF, Clayton MA, Middlebrook JL. Expression of a large, nontoxic fragment of botulinum neurotoxin serotype A and its use as an immunogen. Toxicon. 1995;33(10):1383–6. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(95)00072-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clayton MA, Clayton JM, Brown DR, Middlebrook JL. Protective vaccination with a recombinant fragment of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin serotype A expressed from a synthetic gene in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1995;63(7):2738–42. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2738-2742.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dertzbaugh MT, West MW. Mapping of protective and cross-reactive domains of the type A neurotoxin of Clostridium botulinum. Vaccine. 1996;14(16):1538–44. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JC, Hwang HJ, Sakaguchi Y, Yamamoto Y, Arimitsu H, Tsuji T, et al. C Terminal Half Fragment (50 kDa) of Heavy Chain Components of Clostridium botulinum Type C and D Neurotoxins Can Be Used as an Effective Vaccine. Microbiol Immunol. 2007;51(4):445–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2007.tb03919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webb RP, Smith TJ, Wright PM, Montgomery VA, Meagher MM, Smith LA. Protection with recombinant Clostridium botulinum C1 and D binding domain subunit (Hc) vaccines against C and D neurotoxins. Vaccine. 2007;16:16. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boles J, West M, Montgomery V, Tammariello R, Pitt ML, Gibbs P, et al. Recombinant C fragment of botulinum neurotoxin B serotype (rBoNTB (HC)) immune response and protection in the rhesus monkey. Toxicon. 2006;47(8):877–84. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.02.013. Epub 2006 Mar 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldwin MR, Tepp WH, Pier CL, Bradshaw M, Ho M, Wilson BA, et al. Characterization of the antibody response to the receptor binding domain of botulinum neurotoxin serotypes A and E. Infect Immun. 2005;73(10):6998–7005. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6998-7005.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atassi MZ, Dolimbek BZ, Hayakari M, Middlebrook JL, Whitney B, Oshima M. Mapping of the antibody-binding regions on botulinum neurotoxin H-chain domain 855-1296 with antitoxin antibodies from three host species. J Protein Chem. 1996;15(7):691–700. doi: 10.1007/BF01886751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atassi MZ, Oshima M. Structure, activity, and immune (T and B cell) recognition of botulinum neurotoxins. Crit Rev Immunol. 1999;19(3):219–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oshima M, Hayakari M, Middlebrook JL, Atassi MZ. Immune recognition of botulinum neurotoxin type A: regions recognized by T cells and antibodies against the protective H(C) fragment (residues 855–1296) of the toxin. Mol Immunol. 1997;34(14):1031–40. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(97)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oshima M, Middlebrook JL, Atassi MZ. Antibodies and T cells against synthetic peptides of the C-terminal domain (Hc) of botulinum neurotoxin type A and their cross-reaction with Hc. Immunol Lett. 1998;60(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(97)00124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lukashok SA, Horwitz MS. New Perspectives in Adenoviruses. Current Clinical Topics in Infectious Diseases. 1998;18:286–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyer JL, Kobinger G, Wilson JM, Crystal RG. Adenovirus-based genetic vaccines for biodefense. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16(2):157–68. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi Z, Zeng M, Yang G, Siegel F, Cain LJ, van Kampen KR, et al. Protection against Tetanus by Needle-Free Inoculation of Adenovirus-Vectored Nasal and Epicutaneous Vaccines. J Virol. 2001;75(23):11474–82. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.23.11474-11482.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lubeck MD, Natuk R, Myagkikh M, Kalyan N, Aldrich K, Sinangil F, et al. Long-term protection of chimpanzees against high-dose HIV-1 challenge induced by immunization. Nat Med. 1997;3(6):651–8. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiver JW, Fu TM, Chen L, Casimiro DR, Davies ME, Evans RK, et al. Replication-incompetent adenoviral vaccine vector elicits effective anti-immunodeficiency-virus immunity. Nature. 2002:331–5. doi: 10.1038/415331a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan Y, Hackett NR, Boyer JL, Crystal RG. Protective immunity evoked against anthrax lethal toxin after a single intramuscular administration of an adenovirus-based vaccine encoding humanized protective antigen. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14(17):1673–82. doi: 10.1089/104303403322542310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McConnell MJ, Hanna PC, Imperiale MJ. Adenovirus-based Prime-boost Immunization for Rapid Vaccination Against Anthrax. Mol Ther. 2007;15(1):203–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He TC, Zhou S, da Costa LT, Yu J, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. A simplified system for generating recombinant adenoviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(5):2509–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeng M, Smith SK, Siegel F, Shi Z, Van Kampen KR, Elmets CA, et al. AdEasy system made easier by selecting the viral backbone plasmid preceding homologous recombination. Biotechniques. 2001;31(2):260–2. doi: 10.2144/01312bm04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimura K, Fujii N, Tsuzuki K, Murakami T, Indoh T, Yokosawa N, et al. The complete nucleotide sequence of the gene coding for botulinum type C1 toxin in the C-ST phage genome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;171(3):1304–11. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90828-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoover DM, Lubkowski J. DNAWorks: an automated method for designing oligonucleotides for PCR-based gene synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(10):e43. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao X, Yo P, Keith A, Ragan TJ, Harris TK. Thermodynamically balanced inside-out (TBIO) PCR-based gene synthesis: a novel method of primer design for high-fidelity assembly of longer gene sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(22):e143. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arimitsu H, Lee JC, Sakaguchi Y, Hayakawa Y, Hayashi M, Nakaura M, et al. Vaccination with recombinant whole heavy chain fragments of Clostridium botulinum Type C and D neurotoxins. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11(3):496–502. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.3.496-502.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeng M, Xu Q, Pichichero ME. Protection against anthrax by needle-free mucosal immunization with human anthrax vaccine. Vaccine. 2007 May 4;25(18):3558–94. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.075. [Epub 2007 Jan 26] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Byrne MP, Smith TJ, Montgomery VA, Smith LA. Purification, potency, and efficacy of the botulinum neurotoxin type A binding domain from Pichia pastoris as a recombinant vaccine candidate. Infect Immun. 1998;66(10):4817–22. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4817-4822.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zabner J, Ramsey BW, Meeker DP, Aitken ML, Balfour RP, Gibson RL, et al. Repeat administration of an adenovirus vector encoding cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator to the nasal epithelium of patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(6):1504–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI118573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harvey BG, Hackett NR, El-Sawy T, Rosengart TK, Hirschowitz EA, Lieberman MD, et al. Variability of human systemic humoral immune responses to adenovirus gene transfer vectors administered to different organs. J Virol. 1999;73(8):6729–42. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6729-6742.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hashimoto M, Boyer JL, Hackett NR, Wilson JM, Crystal RG. Induction of protective immunity to anthrax lethal toxin with a nonhuman primate adenovirus-based vaccine in the presence of preexisting anti-human adenovirus immunity. Infect Immun. 2005;73(10):6885–91. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6885-6891.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clayton J, Middlebrook JL. Vaccination of mice with DNA encoding a large fragment of botulinum neurotoxin serotype A. Vaccine. 2000;18(17):1855–62. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jathoul AP, Holley JL, Garmory HS. Efficacy of DNA vaccines expressing the type F botulinum toxin Hc fragment using different promoters. Vaccine. 2004;22(29–30):3942–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pushko P, Parker M, Ludwig GV, Davis NL, Johnston RE, Smith JF. Replicon-helper systems from attenuated Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus: expression of heterologous genes in vitro and immunization against heterologous pathogens in vivo. Virology. 1997;239(2):389–401. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee JS, Pushko P, Parker MD, Dertzbaugh MT, Smith LA, Smith JF. Candidate vaccine against botulinum neurotoxin serotype A derived from a Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus vector system. Infect Immun. 2001;69(9):5709–15. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5709-5715.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee JS, Groebner JL, Hadjipanayis AG, Negley DL, Schmaljohn AL, Welkos SL, et al. Multiagent vaccines vectored by Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicon elicits immune responses to Marburg virus and protection against anthrax and botulinum neurotoxin in mice. Vaccine. 2006;24(47–48):6886–92. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.004. Epub 2006 Jun 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ertl PF, Thomsen LL. Technical issues in construction of nucleic acid vaccines. Methods. 2003;31(3):199–206. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hermanson G, Whitlow V, Parker S, Tonsky K, Rusalov D, Ferrari M, et al. A cationic lipid-formulated plasmid DNA vaccine confers sustained antibody-mediated protection against aerosolized anthrax spores. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(37):13601–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405557101. Epub 2004 Sep 01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duncan SJ, Gordon FC, Gregory DW, McPhie JL, Postlethwaite R, White R, et al. Infection of mouse liver by human adenovirus type 5. J Gen Virol. 1978;40(1):45–61. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-40-1-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fallaux FJ, Bout A, van der Velde I, van den Wollenberg DJ, Hehir KM, Keegan J, et al. New helper cells and matched early region 1-deleted adenovirus vectors prevent generation of replication-competent adenoviruses. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9(13):1909–17. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.13-1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schiedner G, Hertel S, Kochanek S. Efficient transformation of primary human amniocytes by E1 functions of Ad5: generation of new cell lines for adenoviral vector production. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11(15):2105–16. doi: 10.1089/104303400750001417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu Q, Arevalo MT, Pichichero ME, Zeng M. A new complementing cell line for replication-incompetent E1-deleted adenovirus propagation. Cytotechnology. 2006;51:133–40. doi: 10.1007/s10616-006-9023-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]