Abstract

We report a case of ecchordosis physaliphora, an uncommon benign lesion originating from embryonic notochordal remnants, intradurally located in the prepontine cistern, that unusually presented associated with symptoms. MRI detected and precisely located the small mass. At surgery, a cystic gelatinous nodule was found ventral to the pons, contiguous with the dorsal wall of the clivus via a small pedicle. Histological examination diagnosed the lesion as an ecchordosis physaliphora. Here we focus on the analysis of the neuroradiological aspects that play a crucial role from both a diagnostic and a therapeutic standpoint.

Ecchordosis physaliphora (EP) is a benign lesion which arises from ectopic notochordal remnants, lying along the midline craniospinal axis from the clivus to the sacrococcygeal region. It has been described as a small, gelatinous nodule, varying in size from a few millimetres to 2 cm, exhibiting a slow growth pattern.1,2 Intracranial EP is typically found intradurally in the prepontine cistern where it is attached to the dorsal wall of the clivus via a small pedicle, cartilaginous/osseous in origin. EP in this region is usually asymptomatic and found incidentally in 0.4–2% of autopsies.1,2,3,4,5 Hence only a few reports in the literature provide the detailed radiological features of this entity2,4,5,6 with, to our knowledge, only one case reported in neuroradiological journals.5

Case report

A 47‐year‐old woman presented to our institute with a 3 month history of headache and persistent right‐sided facial pain. On physical examination there were no significant abnormalities

Neuroradiological studies

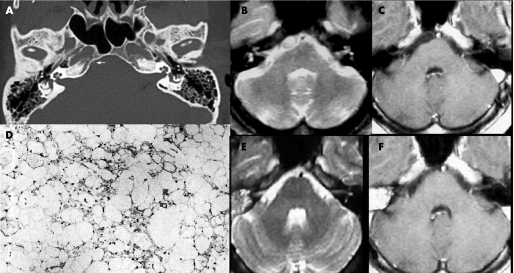

CT, performed before and after contrast administration, showed no abnormalities except for a subtle stalk‐like structure projecting from the dorsal wall of the clivus, appreciable on window bone (fig 1A). MRI of the brain disclosed a small rounded mass, located along the midline in the prepontine cistern, mildly compressing the rostral surface of the pons. The lesion appeared hypointense on T1 weighted images (T1WI) and hyperintense on T2 weighted images (T2WI), and did not enhance after gadolinium administration (fig 1B, C).

Figure 1 (A) CT (bone window) shows a subtle stalk‐like structure projecting from the clivus (arrow). (B, C) Axial MRI ((A) T2 weighted image (T2WI); (B) post‐contrast T1 weighted image (T1WI)) revealed a small well circumscribed mass in the prepontine region, mildly compressing the pons. The lesion appears hyperintense on T2WI (A) and hypointense on T1WI without contrast enhancement (B). (E, F) One year follow‐up axial MRI demonstrates no recurrence of the mass on T2WI (A) and on post‐contrast T1WI (B). (D) Light photomicrograph: hypocellularity of the physaliphorous cells with a lobular growth pattern, eosinophilic and vacuolated cytoplasm with a mixomatous matrix, absence of mitoses and of cellular pleomorphism (haematoxylin‐eosin ×200).

Operation

A standard presigmoidal approach was performed with complete mastoidectomy. Drilling was continued along the pyramid to thin the petrous bone towards its apex. The facial canals as well as the middle and inner ear structures were kept intact while opened air cells were obliterated with bone wax. The superior petrosal sinus was clipped and transacted, and the incision was continued on the tentorium, parallel to the pyramid, and extended through the incisura.

A cystic gelatinous nodule located ventral to the pons was revealed; the mass was easily dissected en bloc. It was apparently attached to the dura mater at the dorsal aspect of the clivus via a small stalk‐like structure. After removal of the cystic portion of the mass, this small stalk‐like osseous process was found to have penetrated the dura of the clivus and was easily removed with a curette.

Postoperative course

The postoperative course was uneventful. Both the headache and facial pain promptly resolved. Postoperative MRI did not reveal residual mass. A 1 year follow‐up MRI evaluation demonstrated no regrowth of the mass (fig 1E, F).

Pathological examination

Microsections of the specimens detected scattered physaliphorous cell nests with a lobular growth pattern.. The cytoplasm was eosinophilic and vacuolated with a mixomatous matrix. No mitotic activity or cellular pleomorphism was revealed by haematoxylin and eosin staining (fig 1D). The pedicle consisted of mature cartilaginous cells. Both the intraoperative findings and these histopathological aspects suggested a diagnosis of EP.

Discussion

Luschka first described the finding of pathological ectopic notochordal tissue at the posterior clivus in 1856.7,8 In 1858, Müller theorised the notochordal origin of EP, subsequently proved in 1894 by Rippert, who coined the definitive term ecchordosis.7 Phylogenetically, the notochord represents the primitive skeleton of vertebrates. It forms during the third week of gestation and becomes the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disk at maturity. Heterotopic rests of notochordal cells are occasionally found outside the nucleus pulposus anywhere along the axial skeleton, such as within the clivus. Although these rests usually have an intraosseous location, they occasionally perforate through the dorsal wall of the clivus into the subdural or subarachnoid space. This could explain the possible pathogenesis of an EP at the prepontine area. Thus EP is thought to be a congenital malformation. Although the term ecchordosis physaliphora for the benign, hamartomatous lesion at the clivus is now widely accepted, there is some confusion about its distinction from intradural chordoma,2,7,8 that is the main differential diagnosis on the basis of the same preferential location. Chordomas, thought to be the malignant counterparts of EP, are rare neoplasms that share with EP the same notochordal origin. In contrast with EP, which is usually intradural, chordomas mostly arise extradurally and lead to bone destruction. On the other hand, rare cases of extraosseous intradural chordoma have been reported and are thought to have a better prognosis than classical chordomas.2,9,10 Furthermore, sometimes EP and chordoma are—apart from an infiltrative growth in chordomas—indistinguishable on the basis of histology, immunohistochemistry and ultrastructural studies. This observation supports the concept of a common origin of the two forms from the notochord.1,8,9,10 Although some histopathological findings, such as hypocellularity, sparse pleomorphism and absence of mitoses,4,11 may be helpful for differentiating EP from chordoma, they are not definitive diagnostic criteria. The MIB‐1 labelling index as a marker of proliferation rate is considered helpful in distinguishing EP from chordomas and is reportedly well correlated with recurrences in chordomas.4,10 Furthermore, immunohistochemical staining is positive for S‐100 protein, keratin and epithelial membrane antigen markers in chordomas thus allowing a correct diagnosis.12 However, it is not clear whether an EP can be a precursor of a chordoma.2,10,13

The differential diagnosis essentially depends on clinical presentation and neuroradiological studies. Because of local bone destruction and a mass effect on brainstem and cranial nerves at the base of the skull, chordomas are generally associated with symptoms. EP, however, is usually asymptomatic, its size and indolent growth patterns considered. In contrast, all reported cases of retroclival intradural chordoma had brainstem symptoms or cranial nerve palsy.7,10,13,14

In the literature, we found only 10 cases of retroclival EP whose neuroradiological findings were fully documented.2,4,6,9 Among them, the five recently reported by Mehnert and colleagues5 had no histological confirmation of diagnosis.

In chordomas, typical CT findings include intratumoral calcification and local invasion of the bone. In EP, CT scan has limited utility because of the small size of the lesion and the possible artefacts in the posterior fossa. It would be helpful in identifying the small pedicle‐like hypertrophic change in the adjacent bone, as in our case.

MR depicts the usual extradural location of chordoma that exhibits inhomogeneous alteration of signal intensity and bone involvement. MR is useful in determining the differential diagnosis,3,6 in both detecting and precisely localising EP at the typical site when thin section images are obtained, even if the signal intensity variations are not specific. In all of the cases reported in the literature, including those that were symptomatic,11,15 EP appears homogeneously hypointense on T1WI and hyperintense on T2WI2,3,4,6,9 without enhancement after gadolinium injection. The lack of enhancement might be considered a distinctive sign3 of an EP, useful in distinguishing it from a quite rare intradural chordoma or other malignant tumours (eg, metastasis).3

In the present case, CT detected only a subtle stalk‐like structure projecting from the clivus that represented a crucial finding in the diagnosis. MR was decisive, detecting a small lesion, homogeneously hypointense on T1WI and hyperintense on T2WI, non‐enhanced after contrast, intradurally located near the midline axis of the clivus without bone involvement. According to Toda and colleagues,3 the site of the lesion is one of the key factors in differentiating EP from other pathological entities.

Because of the symptoms, which were thought to be related to the lesion and were unresponsive to medical therapy, surgery was proposed and successfully performed.

Conclusions

Because of the benign character of EP and the difficulties in its histopathological differentiation from chordomas, precise knowledge of the neuroradiological characteristics of EP is important. On the basis of our experience and a review of literature, contrast enhancement, bone erosion and the presence of clinical symptoms seem to be highly reliable, but not definitive, parameters in the differential diagnosis of intradural chordoma and EP. Furthermore, the presence of subtle hypertrophic changes in the adjacent bone in the form of a thin stalk might be defined as a morphological hallmark of EP and does not exist in other lesions. According to Mehnert and colleagues,5 on the basis of the cases reported in the literature and the current knowledge of the remnants of the notochord, to date there is no significant foundation for defining criteria to distinguish simple notochordal remnants from their aggressive counterparts (ie, chordomas). Such criteria would be helpful in identifying cases that require further procedures, such as follow‐up or surgery.

Abbreviations

EP - ecchordosis physaliphora

T1WI - T1 weighted image

T2WI - T2 weighted image

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Lantos P L, Louis D N, Rosenblum M K.et al Tumours of the nervous system. In: Graham DI, Lantos PL, eds. Greenfield's Neuropathology, vol 2, 7th Edn. London: Arnold, 2002767–1052.

- 2.Rodriguez L, Colina J, Lopez J.et al Intradural prepontine growth: giant ecchordosis physaliphora or extraosseous chordoma? Neuropathology 199919336–340. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toda H, Kondo A, Iwaski K. Neuroradiological characteristics of ecchordosis physaliphora: case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg 199889830–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cha S T, Jarrahy R, Yong W H.et al A rare symptomatic presentation of ecchordosis physaliphora and unique endoscope‐assisted surgical management. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 20024536–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehnert F, Beschorner R, Küker W.et al Retroclival ecchordosis physaliphora: MR imaging and review of the literature. Am J Neuroradiol 2004251851–1855. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macdonald R, Cusimano M, Deck J.et al Cerebrospinal fluid fistula secondary to ecchordosis physaliphora. Neurosurgery 199026515–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfe J T, III, Scheithauer B W. “Intradural chordoma” or “giant ecchordosis physaliphora”? Report of two cases. Clin Neuropathol 1987698–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho K L. Ecchordosis physaliphora and chordoma: a comparative ultrastructural study. Clin Neuropathol 1985477–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe A, Yanagita M, Ishii R.et al Magnetic resonance imaging of ecchordosis physaliphora: case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 199434448–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishigaya K, Kaneko M, Ohashi Y.et al Intradural retroclival chordoma without bone involvement: no tumor regrowth 5 years after operation—case report. J Neurosurg 199888764–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng S H, Ko S F, Wan Y L.et al Cervical ecchordosis physaliphora: CT and MR features. Br J Radiol 199871329–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lountzis N I, Hogarty M D, Kim H J.et al Cutaneous metastatic chordoma with concomitant tuberous sclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 200655(2 Suppl)6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mapstone T, Kaufman B, Ratcheson R. Intradural chordoma without bone involvement: nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) appearance—case report. J Neurosurg 198359535–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardie R C. Magnetic resonance appearance of a rare intradural chordoma. Wis Med J 199291627–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurokawa H, Miura S, Goto T. Ecchordosis physaliphora arising from the cervical vertebra, the CT and MRI appearance. Neuroradiology 19983081–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]