Abstract

Previously, this laboratory demonstrated that ethanol treatment significantly reduces the number of developing serotonin (5-HT) and other fetal rhombencephalic neurons in rats by augmenting apoptosis. Using a 5-HT1A agonist we were able to attenuate the ethanol-associated reduction and apoptosis of 5-HT and rhombencephalic neurons. The downstream pro-survival effects of 5-HT1A stimulation were associated with the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3′kinase (PI-3K) and its subsequent up-regulation of specific NF-κB dependent pro-survival genes.

Using an in vitro model, we investigated the hypothesis that S100B, a protein Which is released from astrocytes following 5-HT1A agonist stimulation, can reduce apoptosis in ethanol-treated rat fetal rhombencephalic neurons. We also evaluated whether the anti-apoptotic effects of S100B on fetal rhombencephalic neurons were linked to the activation of the PI-3K→ pAkt pro-survival pathway and the expression of two NFκB-dependent pro-survival genes: XIAP and Bcl-2. Moreover, we determined whether S100B's pro-survival effects were associated with mitogen activated protein kinase kinase (MAPKK) → p42/p44 MAPK.

The results of these investigations demonstrated that S100B treatment prevented ethanol-associated apoptosis of fetal rhombencephalic neurons. In addition, it appears that these neuroprotective effects are linked to activation of the PI-3K pathways, because the PI-3K inhibitor LY29004 blocks the neuroprotective effects of S100B. Moreover, S100B increases the formation of pAkt and the up-regulation of two downstream NFκB-dependent pro-survival genes: XIAP and Bcl-2. Although the MAPKK inhibitor PD98059 reduced the number of surviving neurons in S100B-treated cultures, S100B did not activate MAPKK.

Keywords: ethanol, S100B, apoptosis, neuroprotection, Akt, XIAP, Bcl-2

1. Introduction

CNS neurons are highly susceptible to the damaging effects of ethanol during their development. Among the developing neurons that are reduced by ethanol are the serotonin (5-HT) neurons of the dorsal and median raphe and B9 complex (Tajuddin and Druse, 1999; 2001; Sari et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2001). Ethanol also reduces the number of developing cerebellar granule and Purkinje neurons (Bonthius et al., 1996; Light et al., 2002; Maier et al., 1999; Marcussen et al., 1994), hippocampal neurons (Miller, 1995; Moulder et al., 2002), and cortical neurons (Jacobs & Miller, 2001). In vitro studies suggest that the mechanism by which ethanol decreases the number of fetal 5-HT immunopositive neurons is apoptosis (Druse et al., 2004; 2005). Ethanol treatment also causes apoptosis in the developing neural crest (Cartwright et al., 1998; Dunty et al., 2001; Liesi, 1997), cortical cells (Cheema et al., 2000), cerebellar granule cells (Castoldi et al., 1998; Ramachandran et al., 2001), and forebrain cells (Ikonomidou et al., 2000).

The ethanol-mediated reduction of developing 5-HT neurons is accompanied by a marked decrease in 5-HT content in the brain stem of fetal rats and in cortical areas of postnatal animals (Rathbun et al., 1985; Tajuddin and Druse, 1993; Druse et al., 1991). This reduction of 5-HT in the fetal brain stem is likely to augment the damaging effects of ethanol on the developing brain, because fetal 5-HT functions as an essential neurotrophic factor that promotes the development of 5-HT neurons, targets of 5-HT neurons, and other CNS neurons (Azmitia et al., 1996; Kim and Druse, 1996; Lauder & Krebs, 1978; Lauder, 1990; Whitaker-Azmitia et al., 1996). We were able to attenuate the ethanol-associated reduction of fetal 5-HT neurons by treating pregnant ethanol-fed rats with a 5-HT1A agonist (Tajuddin and Druse, 1999; 2001). Moreover, a 5-HT1A agonist prevented ethanol-associated apoptosis in cultured fetal 5-HT and other rhombencephalic neurons (Druse et al., 2004; 2005). Apoptosis is reduced in cultured fetal rhombencephalic neurons through the actions of 5-HT1A agonists on neuronal receptors (Druse et al., 2005). The downstream pro-survival effects of 5-HT1A stimulation appear to include activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3′kinase (PI-3K) pathway and its subsequent regulation of specific NF-κB dependent pro-survival genes (Druse et al., 2006), i.e., Bcl-xl and Xiap.

Although in vitro studies with cultured neurons demonstrate the involvement of neuronal 5-HT1A agonists in the neuroprotective effects of these drugs, their in vivo pro-survival effects are likely to be mediated both by neuronal and astroglial 5-HT1A receptors (Whitaker-Azmitia et al., 1990; Azmitia et al., 1996). The latter effects involve S100B, which is detected at nanomolar concentrations in the media following stimulation of astroglial 5-HT1A receptors (Eriksen et al., 2001). In fact, the ability of astroglial conditioned media, produced following 5-HT1A agonist stimulation, to prevent an ethanol-associated reduction of 5-HT neurons is blocked by an antibody to S100B (Eriksen et al., 2001). Moreover, nanomolar concentrations of S100B exert anti-apoptotic effects on hippocampal neurons treated with glutamate, staurosporine, or glucose deprivation (Ahlemeyer et al., 2000), and on neuroblastoma cell lines treated with Aβ amyloid (Businaro et al., 2006) or undergoing serum withdrawal (Huttunen et al., 2000).

Nanomolar concentrations of S100B also exert neurotrophic effects (Huttunen et al., 2000; Van Eldik et al, 1991) and promote the maturation of both 5-HT neurons and astrocytes. As little as 1 - 50 nM of S100B stimulates the development of 5-HT neurons in vitro, as measured by the increased appearance of 5-HT reuptake sites and augmented neurite outgrowth (Azmitia et al., 1990; Nishi et al., 1997; Huttunen et al., 2000). However, at high (μM) concentrations of S100B, this protein exerts neurotoxic effects (Huttunen et al., 2000; Businaro et al., 2006; Sorci et al., 2004), and may augment the damaging effects of Aβ amyloid (Businaro et al., 2006).

Reportedly, the neuroprotective effects and some neurotoxic effects of S100B are mediated by its actions on the RAGE receptor (Receptor for Advanced Glycation End products) (Donato et al., 2001; Huttunen et al., 1999; 2000; Kögel et al., 2004; Businaro et al., 2006); additional neurotoxic effects of S100B are mediated in a RAGE independent manner (Sorci et al., 2004). In certain cells and cell lines, RAGE activation is accompanied by increased activity of p42/p44 mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) (Goncalves et al., 2000; Huttunen et al., 2002), increased Bcl-2 expression (Huttunen et al., 2000), and activation of NF-κB (Huttunen., 1999; 2000; Kögel et al., 2004). Activation of specific downstream effectors is dependent on whether S100B is present at neuroprotective or neurotoxic concentrations. High concentrations of S100B reportedly stimulate iNOS in cortical astrocytes (Lam et al., 2001).

In this study, we investigated the hypothesis that nanomolar concentrations of the astroglial protein S100B can reduce apoptosis in ethanol-treated fetal 5-HT and other rhombencephalic neurons by activating a pro-survival pathway linked either to MAPKK or phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase (PI-3K). Fetal rhombencephalic neurons were cultured in the presence and absence of ethanol and/or 30 ng/ml of the S100B dimer; this concentration of S100B is comparable to that which exerts neurotrophic and anti-apoptotic effects. Following these treatments, we quantified the percentage of apoptotic and surviving neurons and we assessed the ability of S100B to increase the phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK and pAkt. We used inhibitors of MAPKK and PI-3K to verify the specificity of S100B's pro-survival effects and to identify the potential signaling pathways involved with these effects. In addition, we examined the effects of ethanol and S100B on the expression of two NFκB-dependent pro-survival genes: Xiap and Bcl-2. Bcl-2 expression was examined because of its reported association with the effects of S100B (Heaton et al., 2000). Expression of Xiap was studied because up-regulation of this gene appears to be involved with the protective effects of 5-HT1A agonists on ethanol-treated fetal rhombencephalic neurons (Druse et al., 2006).

2. Results

Treatment of fetal rhombencephalic neurons with 50 mM ethanol increases apoptosis and S100B prevents the ethanol-associated damage

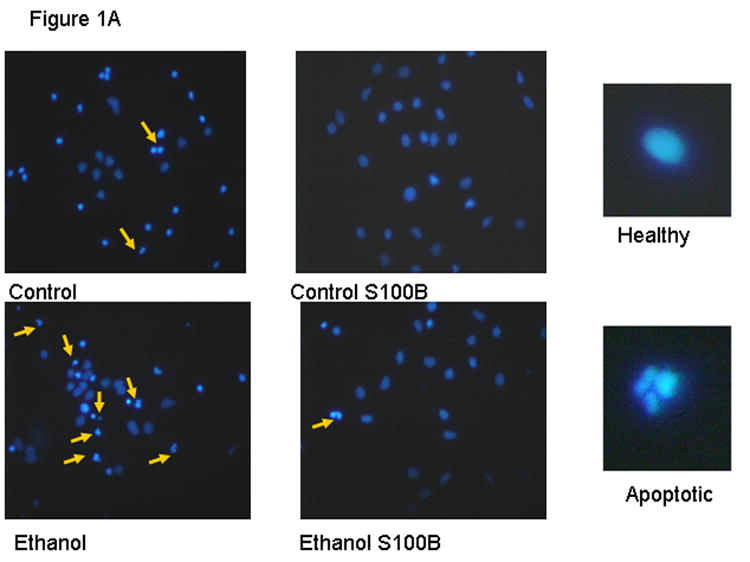

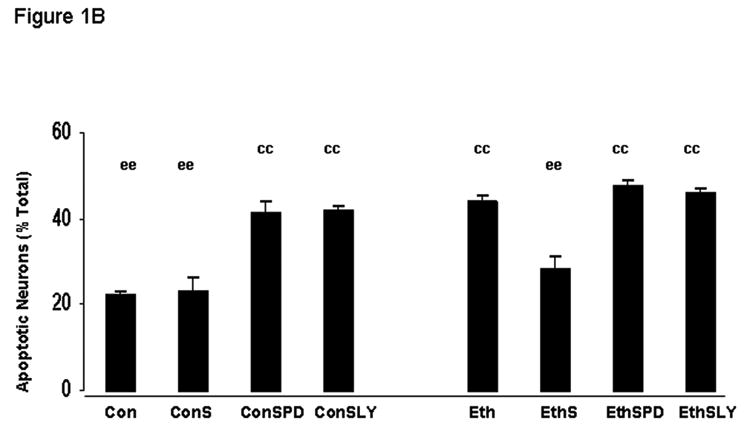

Figure 1A shows fetal rhombencephalic neurons that were stained with Hoechst 33342 following a 24-hour treatment with 50 mM ethanol and/or 30 ng/ml of S100B. Examples of healthy and apoptotic neurons are shown at higher power. Figure 1B is a graphic depiction of data obtained from multiple separate experiments. There were 10-12 separate experiments using neurons treated with either ethanol or S100B; the inhibitors PD and LY were included in 3 experiments. Treatment of fetal rhombencephalic neurons with 50 mM ethanol (DIV5 to DIV6) significantly increased the percentage of apoptotic neurons. This doubled the percent of apoptotic neurons from 22% to 44% [F(1,41) = 20.5, p < .0001, control vs. ethanol, p < .01]. Importantly, co-treatment with 30 ng/ml of the S100B dimer prevented the pro-apoptotic effects of 50 mM ethanol (p < .01). In the presence of the inhibitors of PI-3K (LY294002) and MAPKK (PD98059), S100B did not exert neuroprotective effects of S100B. In addition, these inhibitors caused a significant increase in the percentage of apoptotic neurons in control cultures (> 45%), but they did not augment apoptosis in cultures of ethanol-treated neurons.

Figure 1. Ethanol reduces survival and promotes apoptosis of fetal rhombencephalic neurons in vitro, and S100B prevents the pro-apoptotic effects of 50 mM ethanol.

Figure 1A shows fetal rhombencephalic neurons stained with Hoechst 33342 from cultures that were maintained under control conditions (no ethanol) or that were treated for the last 24 hours (DIV5 to DIV6) with 50 mM ethanol (ethanol) and/or 30 ng/ml of S100B. Hoechst-stained living and apoptotic neurons were identified as described. A higher magnification was used to identify neurons that exhibit the characteristics of apoptotic cells; apoptotic cells are identified by the arrows. Figure 1B is a graphic depiction of the percentage of apoptotic neurons in cultures of fetal rhombencephalic neurons that were maintained under control (con) conditions (no ethanol) in the presence and absence of ethanol (eth); S100B (S); 10 μM LY294002 (LY), an inhibitor of PI-3K; or 10 μM PD98059 (PD), an inhibitor of MAPKK. Statistical differences are noted when the values for one of the experimental groups is significantly (p < .01) different from the control (no treatment) group (cc) or the ethanol-treated group (ee). A significant main effect of ethanol was detected [F(1,41) = 20.5, p < .0001].

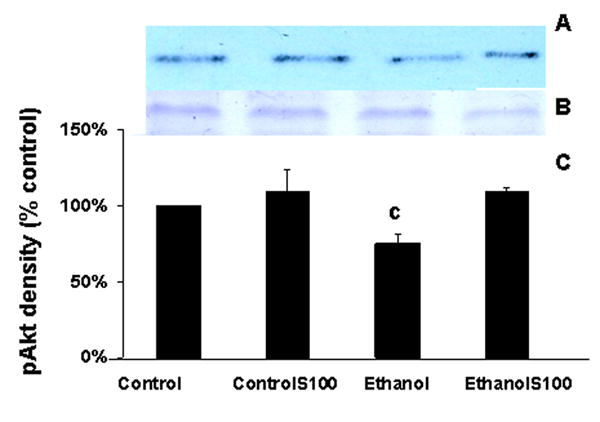

S100B activates PI-3K to phosphorylate Akt in ethanol-treated cultures of fetal rhombencephalic neurons

Figures 2A depicts a representative Western blot (2A) of bands probed with an antibody to pAkt. Figure 2B shows the actin bands (2B) in the corresponding lanes of a gel stained with Coomassie blue. Samples were obtained from cultures of fetal rhombencephalic neurons that were treated with 50 mM ethanol for 24-hours and/or with 30 ng/ml of S100B for 10 minutes. Figure 2C is a graphic summary of the data obtained from five separate experiments. The depicted data is presented as a percentage of the control values. In each of the five experiments ethanol treatment reduced the level of pAkt and the mean decrease was 25% (p < .01). However, stimulation of ethanol-exposed cultures with S100B consistently brought the pAkt levels back to at least that of controls. Although S100B stimulated PI-3K → pAkt in ethanol-treated cultures, it did not augment the activity of PI-3K in control cultures (no ethanol). In the presence of LY294002, pAkt was reduced to ∼ 13% of control values (data not shown).

Figure 2. Ethanol treatment reduces PI-3K→pAkt and S100B prevents the ethanol-associated decrease.

The data depicted in Figure 2 come from separate experiments in which fetal rhombencephalic neurons were cultured in the presence of 50 mM ethanol for 24 hours and then stimulated with S100B for 10 minutes as described. Figures 2A and 2B, respectively, show a representative Western blot and actin bands from a corresponding gel that was stained with Coomassie blue; actin was used as a loading control. Figure 2C provides a graphic summary of the data collected from five separate experiments. In each experiment, values were adjusted to the percentage of control values. There was a significant reduction in pAkt in cultures from ethanol-treated neurons as compared to cultures from control neurons (no treatment) (c, p < .05). The abbreviations controlS100 and ethanolS100 refer, respectively, to neurons that were cultured in the presence of S100B and either control or ethanol-containing media.

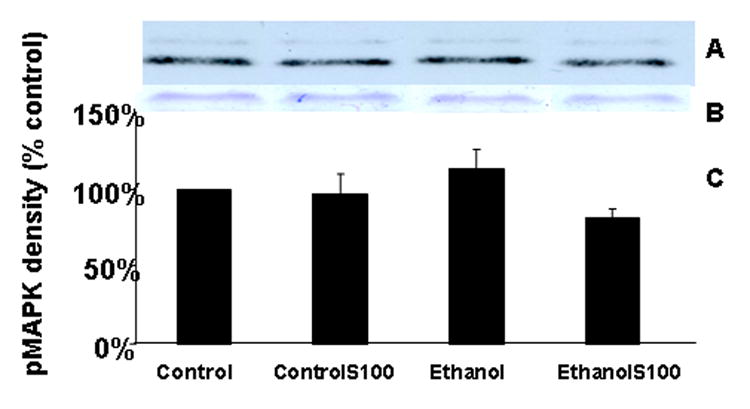

In contrast to the effects of ethanol and S100B on the PI-3K → pAkt pathway, we did not detect any significant effects of these agents on the MAPKK → MAPK pathway after a 10-minute treatment with S100B

Figures 3A and 3B depict a representative Western blot (3A) and the actin bands (3B) in the corresponding lanes of a gel stained with Coomassie blue. Figure 3C is a graphic summary of the data obtained from five separate experiments. The depicted data is presented as a percentage of the control values. In each of the five experiments neither ethanol nor S100B treatment consistently or significantly altered the level of level of p42/p44MAPK (p > .05).

Figure 3. Lack of effect of ethanol or S100B on p42/p44MAPK in fetal rhombencephalic neurons.

The data depicted in Figure 3 come from separate experiments in which fetal rhombencephalic neurons were cultured in the presence of 50 mM ethanol for 24 hours and then stimulated with S100B for 10 minutes. Figures 3A and 3B, respectively, include a representative Western blot and the actin bands from a corresponding gel that was stained with Coomassie blue. Figure 3C provides a graphic summary of the data collected from five separate experiments. In each experiment, values were adjusted to the percentage of control values. p42/p44 MAPK levels were not significantly affected by ethanol and/or S100B treatment (p > .05). The abbreviations controlS100 and ethanolS100 refer, respectively, to neurons that were cultured in the presence of S100B and either control or ethanol-containing media.

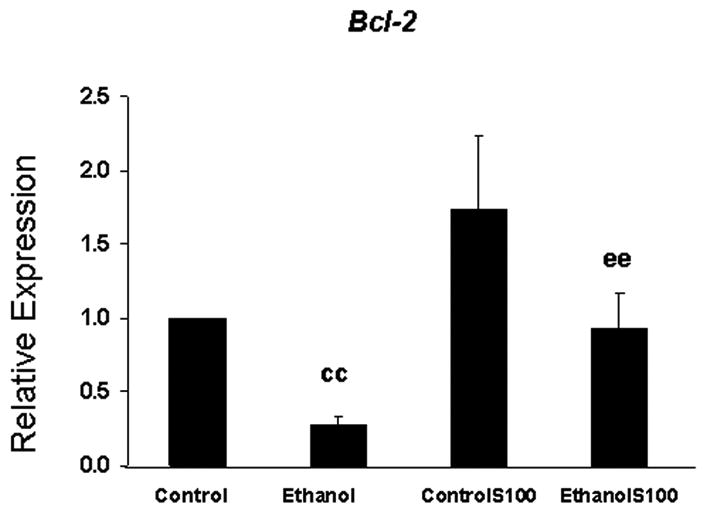

Treatment of fetal rhombencephalic neurons with 50 mM ethanol markedly reduced the expression of the gene encoding Bcl-2 and S100B prevented the ethanol-associated reduction (Figure 4)

Figure 4. Bcl-2 mRNA is reduced in fetal rhombencephalic neurons that were cultured in the presence and absence of ethanol, and S100B increased levels of Bcl-2 mRNA in ethanol-treated cultures.

Each value was obtained from five separate experiments and represents the mean ± the SEM of the fold change in the level of Bcl-2 mRNA; values were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method. In each experiment fetal rhombencephalic neurons were treated during the last 28 hours with 50 mM ethanol and during the last 4 hours with 30 ng/ml of S100B. In comparison with control cultures (cc), no treatment), expression of Bcl-2 was significantly reduced by ethanol (p < .01). Following the addition of S100B to ethanol-treated cultures (ee) the mean increase in expression of Bcl-2 was 4-fold. The abbreviations controlS100 and ethanolS100 refer, respectively, to neurons that were cultured in the presence of S100B and either control or ethanol-containing media.

In comparison with control cultures (cc), expression of Bcl-2 was significantly reduced (p < .01) in ethanol-treated cultures in each of six separate experiments (Figure 4); the mean reduction was 75%. In contrast, the values in ethanol- plus S100B-treated cultures were markedly higher (p < .01) than those of the ethanol-treated group (ee) and they were comparable to those in control cultures. Following the addition of S100B to ethanol-treated neurons, the mean increase in expression of Bcl-2 was 4-fold.

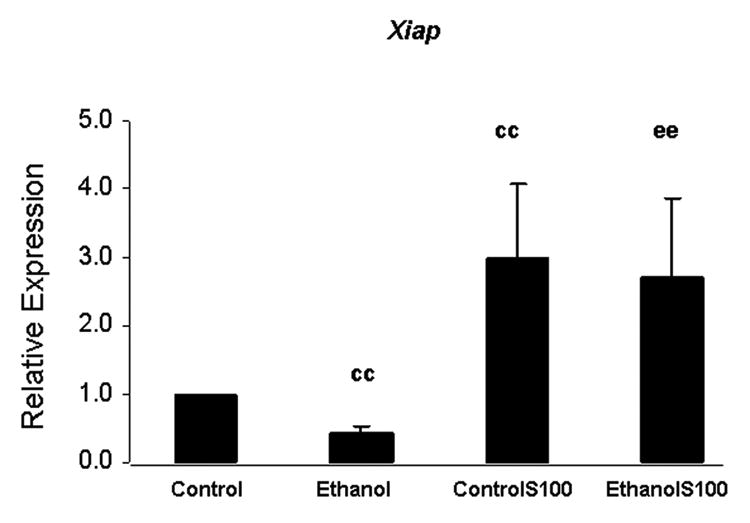

Treatment of fetal rhombencephalic neurons with 50 mM ethanol markedly reduced the expression of Xiap (p < .01) relative to that in control cultures (cc); the mean reduction was 50% (Figure 5). In comparison to unstimulated control (cc) and ethanol-treated (ee) cultures, addition of S100B increased Xiap expression in the controlS100B and ethanolS100B groups (p < .01); it also prevented the ethanol-associated reduction (Figure 5). When compared with the unstimulated control and ethanol-treated cultures, the mean stimulation of Xiap expression by S100B was ∼ 3-fold.

Figure 5. Xiap mRNA is reduced in fetal rhombencephalic neurons that were cultured in the presence and absence of ethanol, and S100B increased levels of Xiap mRNA.

Each value was obtained from six separate experiments and represents the mean ± the SEM of the fold change of Xiap mRNA; values were calculated using the 2 -ΔΔCT method. In each experiment fetal rhombencephalic neurons were cultured during the last 28 hours with 50 mM ethanol and during the last 4 hours with 30 ng/ml of S100B. In comparison to control cultures (cc, no treatment), ethanol significantly reduced the expression of Xiap (p < .01). When compared with the unstimulated control (cc) and ethanol-treated cultures (ee), the mean stimulation of Xiap expression by S100Bwas ∼ 3-fold (p < .01). The abbreviations controlS100 and ethanolS100 refer, respectively, to neurons that were cultured in the presence of S100B and either control or ethanol-containing media.

3. Discussion

The astroglial protein S100B prevented apoptosis in cultures of ethanol-treated fetal rhombencephalic neurons; S100B reduced the percentage of apoptotic neurons in ethanol-treated cultures from ∼44% to ∼28%, a value that is not significantly greater than that in untreated control cultures. We would expect that both serotonergic and non-serotonergic neurons were protected by S100B treatment in the current study, because an earlier study from this laboratory showed that ethanol augmented apoptosis in both 5-HT immunopositive and non-serotonergic neurons. That study also demonstrated that 5-HT immunopositive neurons comprise only 20% to 30% of the total population of fetal rhombencephalic neurons cultured under identical conditions (Druse et al., 2004).

The present investigation suggests that S100B exerts direct anti-apoptotic effects on cultured fetal rhombencephalic neurons. Direct protective effects of S100B are also indicated by reports of in vitro studies showing that nanomolar concentrations of S100B prevent the ethanol-associated reduction in 5-HT neurons (Eriksen and Druse, 2001), and protect hippocampal neurons from the damaging effects of glutamate, staurosporine, and glucose deprivation (Ahlemeyer et al., 2000). Treatment with S100B is also associated with anti-apoptotic effects on neuroblastoma cell lines treated with Aβ amyloid (Businaro et al., 2006) or serum withdrawal (Huttunen et al., 2000). Nonetheless, micromolar concentrations of S100B exert neurotoxic effects (Huttunen et al., 2000; Businaro et al., 2006; Sorci et al., 2004) and appear to augment the neurotoxic effects of Aβ amyloid (Businaro et al., 2006).

In the in vivo situation, S100B release involves an interaction of astrocytes and neurons. S100B is released from astrocytes in response to the stimulation of astroglial 5-HT1A receptors (Whitaker-Azmitia et al., 1990; Eriksen et al., 2001) by 5-HT that is produced and secreted by neurons In fact, 5-HT1A agonist stimulation causes the release of nanomolar concentrations of S100B from astroglia (Eriksen et al., 2001; Ahlemeyer et al., 2000). However, analogous interactions of neurons and astrocytes are not likely to occur under the present in vitro conditions where gliogenesis was arrested by Ara-C and GFAP-immunopositive astrocytes account for <5% of the cells.

The results of the present study suggest that the damaging effects of ethanol on fetal rhombencephalic neurons as well as the neuroprotective effects of S100B on ethanol-treated neurons are likely to involve changes in the PI-3K pro-survival pathway and the downstream phosphorylation of Akt (Downward, 2004). This conclusion is supported by the evidence that treatment of fetal rhombencephalic neurons with 50 mM ethanol is associated with increased apoptosis as well as reduced formation of pAkt. Both of these aberrant effects are prevented by S100B. In addition, S100B treatment of ethanol-exposed neurons is accompanied by an increase in pAkt. Moreover, the present studies suggest that LY294002 blocks the effects of S100B on ethanol-treated neurons, because this drug prevents the protective effects of S100B. Although LY294002 also augments apoptosis in control neurons it does not further increase the percentage of apoptotic neurons in ethanol-treated cultures. The different responses of control and ethanol-treated cultures to the PI-3K inhibitor may be due to the presence of a factor in control cultures that stimulates PI-3K, and the absence or reduction of this factor in ethanol-treated cultures. We expect that 5-HT might be this factor because ethanol reduces the number of 5-HT neurons in these cultures (Druse et al., 2004) and in brains of the offspring of ethanol fed rats (Tajuddin and Druse, 1999; 2001); ethanol also reduces 5-HT in the brainstem of fetal offspring by ≥ 50% (Druse et al., 1991).

This study also suggests that the damaging effects of ethanol and the neuroprotective effects of S100B involve downstream effectors of the PI-3K pathway, i.e., NF-κB dependent pro-survival genes. Among these genes (Kucharczak et al., 2003) are the two NF-κB dependent pro-survival genes that were examined in the present study: Bcl-2 and Xiap. Ethanol treatment of fetal rhombencephalic neurons reduced the expression of both genes, and S100B prevented a significant reduction in their expression in ethanol-treated neurons. The ethanol-associated observations are consistent with those from earlier reports from this laboratory. Previously, we detected an ethanol-associated reduction in the phosphorylation of Akt (Druse et al., 2005) and decreased expression of Xiap and Bcl-2 as well as additional NF-κB dependent genes that were investigated in the latter study: cIAP1, cIAP2, and Bcl-xl (Druse et al., 2006).

Interestingly, S100B stimulated the phosphorylation of Akt and increased the expression of Xiap and Bcl-2 in control neurons as well as those treated with ethanol. However, augmentation of the pro-survival pathway did not result in an increased percentage of non-apoptotic control neurons. The fact that survival was not increased in control neurons suggests that compensatory mechanisms in control neurons prevented a hyper-activation of the pro-survival response. Potentially such compensatory mechanisms could include decreased translation of the mRNA or increased degradation of the protein product.

Bcl-2 can bind to proapoptotic proteins such as Bax, thus preventing the formation of pores in the outer mitochondrial membrane and subsequent release of apoptogenic factors such as cytochrome c and apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) into the cytosol (Ikonomidou et al., 2000). XIAP is a member of the IAP family that inhibits activated caspase-3 and caspase-7 (Roy et al., 1997; Deveraux, et al., 1998) and blocks cytochrome c-stimulated conversion of procaspase-9 to the active form of caspase-9. By blocking the activation of caspase-9, XIAP inhibits the cytochrome c pathway of apoptosis upstream of caspase-3 activation (Deveraux et al., 1997; 1998). Thus, it is likely that a reduction in Bcl-2 and XIAP would contribute to the reduced survival in ethanol-treated fetal rhombencephalic neurons and that an increase in the expression of Bcl-2 and Xiap might prevent the damaging effects of ethanol.

Although the present observations are consistent with reports of other investigators who find that S100B's neurotrophic effects are accompanied by increased Bcl-2 expression (Huttunen et al., 2000) and activation of NF-κB (Huttunen et al., 1999; 2000; Kögel et al., 2004), they differ from those that link the Bcl-2 effects with increased activity of p42/p44 MAPK (Goncalves et al., 2000; Huttunen et al., 1999). In the present investigation, the formation of p42/p44MAPK was not altered by a 10-minute treatement with S100B or by a 24-hour treatment with 50 mM ethanol.

It appears that the protective effects of both S100B (present study) and a 5-HT1A agonist (Druse et al., 2005) are mediated by the PI-3K pathway rather than the MAPKK pathway in fetal rhombencephalic neurons. However, the MAPKK pathway is reportedly linked to the downstream effects of S100B in astrocytes (Goncalves et al., 2000) and to that of a 5-HT1A receptor agonist in cell lines (Cowen et al., 1996; Garnavskoya et al., 1996). These differences are likely due to developmental and cell specific differences regarding the presence or absence of specific receptors and downstream effectors of specific signaling pathways.

Although both S100B and 5-HT1A agonists protected fetal rhombencephalic neurons from the pro-apoptotic effects of ethanol and the pro-survival effects of both agents appear to be linked to the PI-3K pathway, it is likely that there are at least subtle differences in their effects. For example, the expression of Bcl-XL and Xiap but not of Bcl-2 were increased in ethanol-exposed neurons treated with the 5-HT1A agonist, ipsapirone (Druse et al., 2006). In contrast, S100B treatment increased the expression of the gene encoding Bcl-2 and Xiap. Thus, ff PI-3K is involved with both the effects of S100B and 5-HT1A agonists, additional regulators of gene transcription are likely to be involved.

4. Experimental Procedures

Tissue Dissection and Dissociation of Cells

As described previously by this laboratory, primary cultures of fetal neurons were obtained from the rhombencephalon of gestation day 14 (G14) Sprague-Dawley rats (Eriksen et al., 2002). This brain region was used because the G14 rat rhombencephalon contains the developing serotonergic raphe neurons (König et al., 1989). All animal care and use procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Loyola University Chicago, Stritch School of Medicine.

Neuronal Cell Cultures and Treatments with Ethanol and S100B

Dissected tissue from 2-3 litters per experiment was mechanically disaggregated using 230 and 130 micron Nitex bags (Sefar America, HR Williams Division, Kansas City, MO) and the suspension was collected (Eriksen et al., 2002). On the 1st day in vitro (DIV1), dispersed cells were seeded at a comparable density onto either four-chambered slides (Nalge and Nunc, Naperville, IL) or plates (Corning, Corning, New York) that were previously coated with poly-D-lysine. Four-chambered slides (1.8 cm2/chamber) were used for Hoechst analyses and 55 cm2 plates were used to prepare neurons for protein and mRNA extraction. In all studies, the media contained ethanol at a concentration of 0 mM (control) or 50 mM (ethanol), and we cultured cells at a density that was comparable to that used in our previous investigations (Druse et al., 2004; 2005; 2006). This density was ∼260,000 cells/chamber or 8 × 106 cells per plate. Cells were cultured in a neuron-specific chemically defined media (CDM) that is a Dulbecco's Minimal Essential Media/F12 (DMEM/F12) media, containing hydrocortisone-21 sulfate, Basal Medium Eagle Vitamin Solution, antibacterial agent gentamicin sulfate (Honegger et al., 1997), and B27 serum-free medium supplement (Brewer et al., 1993); this CDM was supplemented with 0.25% fetal bovine serum (Druse et al., 2004; 2005). After 24 hours, all media included 0.4 μM cytosine arabinoside (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to arrest astrocyte growth and proliferation. Thereafter, media was changed on alternate days and at the time of treatment. All cultures were maintained in control media (no ethanol) for 4 days (DIV 1 to DIV5). From DIV5 to DIV6 half of the cultures were maintained in control media and half in the 50 mM ethanol-containing media. Prior research shows that the ethanol concentration in the media remains at ≥ 85% of that initially established in the ethanol chamber system used by this laboratory (Eriksen et al., 2001).

For Hoechst analyses, control and ethanol-treated cultures were co-treated with a trophic concentration of S100B, i.e., 30 ng/ml of the dimeric form of S100B, from DIV5 to DIV6; for real-time RT-PCR studies S100B was present for 4 hours on DIV6. For studies of signaling pathways (i.e., Western blot analyses), we replaced media from DIV6 cultures with a serum-free CDM that also contained phosphatase inhibitors (200 μM sodium orthovanadate and 10 mM sodium fluoride) one hour prior to the addition of S100B. At the end of the 1-hour period, S100B was then added at a concentration of 30 ng/ml for 10 minutes. LY294002 or PD98059, inhibitors of PI-3K and MAPKK, respectively were included with S100B. Both inhibitors were used at a concentration of 10 μM because this laboratory finds that these inhibitor concentrations effectively (>90%) reduce pAkt and p42/p44 MAPK in unstimulated cultures; we also find that these concentrations do not have a marked effect on the other signaling pathway under investigation.

Identification of live cells and those with fragmented apoptotic nuclei using Hoechst 33342

Using an established method (Arndt-Joven, et al., 1977), familiar to this laboratory (Druse et al., 2004; 2005), we identified apoptotic cells that were stained with Hoechst 33342. Previously, we showed that Hoechst 33342, which visualizes fragmented nuclei, and TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end-labeling), which labels fragmented DNA in apoptotic cells, identify the identical population of apoptotic fetal rhombencephalic neurons in control and ethanol-treated cultures (Druse et al., 2004). A Nikon Microphot fluorescence microscope was used in the ultraviolet range to view Hoechst-stained cells. Images were captured using a 40X objective and analyzed at a higher, computer-enhanced magnification (≥100X). Typically, 275 to 400 control neurons were analyzed methodically without consideration of treatment; neurons were counted on 10 fields from two chambers (5 fields/chamber). As described previously (Druse et al., 2004; 2005), neurons that were identified as apoptotic cells appeared to be intact and contained fragmented apoptotic nuclei; alive/non-apoptotic cells exhibited an intact cellular morphology and lacked fragmented nuclei. Necrotic cells, e.g., those exhibiting signs of swelling and the presence of diffuse or finely clumped chromatin, were not observed. In a prior report, this laboratory noted that the ara-C treatment reduces the percentage of astrocytes in the cultures to less than 5% (Druse et al., 2004). Extracellular debris, fragmented cells, and ‘dots’, whether of neuronal or glial origin, were not included in the cell counts.

Western Blot Analyses

At the end of the experiments, media was removed, cells were rinsed with 0.01 M PBS, pH 7.6, lysis buffer was added, and cells were scraped into the lysis buffer and sonicated. Lysis buffer contained protease inhibitors (leupeptin, aprotinin, pepstatin A, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Denatured and reduced proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gels along with molecular weight markers (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Separated proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, using 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 as a blocking agent. Blots were probed either with a primary antibody against the phosphorylated form of Akt (pAkt) or against p42/p44 MAPK (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA). As described previously (Druse et al., 2005), we used a secondary antibody that was conjugated to horse radish peroxidase and ECL (excitation of chemiluminescence) detection. Each film was overlaid on its paired blot to make sure that bands of the appropriate molecular weights were identified by the antibodies to pAkt and p42/p44MAPK. Using the NIH Macintosh-based image analysis program, i.e., Image, we determined the relative optical densities of bands on the autoradiograms that corresponded to either pAkt or p42 and p44MAPK. The densities of the major band, p42 MAPK, and the minor band, p44 MAPK, were combined. To adjust for potential differences in loading, we compared film densities of bands for pAkt, p42MAPK and p44MAPK to that of actin on Coomassie blue stained gels.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

As described previously (Druse et al., 2006) we used Trizol reagent (Life Technology, Gaithersburg, MD) to extract total RNA from cultured fetal rhombencephalic neurons; 20 mg/ml of glycogen (Ambion, Austin, TX) was included in order to facilitate the precipitation of RNA and to maximize the yield of RNA. After dissolving RNA in 25 μl of DEPC-treated H2O, which was treated with DNA-free (Ambion) to remove contaminating genomic DNA, it was stored at −80° until use. Single strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 to 2 μg of total RNA (DNA-free) using the First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ).

cDNA (DNA equivalent of 40 ng to 20 ng of total RNA) was used at a dilution of 1:2 or 1:4 in a total volume of 20 μl of 1X Platinum Quantitative PCR Super Mix-UDG (1.5 U Platinum Taq DNA polymerase, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 200 mM dGTP, 200 mM dATP, 200 mM dCTP, 400 mM dUTP, 1 U UDG) (Life Technology), 0.25 mM Rox (Life Technology), 1/40,000 SYBR Green (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon), and 0.25 μM primers (Druse et al., 2006). PCR amplifications were performed in triplicate using a Perkin-Elmer Gene Amp 7300 Sequence Detector thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). RT-PCR data was analyzed using SDS software (Applied Biosystems). Expression of the GAPDH was used to normalize sample inputs.

As noted previously, a series of plasmid containing target genes were used to generate standard curves for real-time quantitative RT-PCR assays (Druse et al., 2006). A standard curve was established using serial dilutions of known amounts of the input copy number of target genes, which was based on the following equation: 1 ng plasmid DNA = 2.2 × 108 copies. Standard curves for GAPDH and genes of interest (10-100,000 copies/μl) were performed in each experiment. In each experiment, a triplicate RT-PCR reaction without cDNA or known DNA template was included for each set of primers. Specific primary sequences for Xiap and Bcl-2 were selected using the Primer Express program (Applied Biosystems) and sequences available from the NCBI database. Primers were synthesized by Life Technology. The forward (f) and reverse (r) primer sequences for rat genes are described in an earlier publication (Druse et al., 2006).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical significance of data from Hoechst and Western blot analyses was determined using a 2-way ANOVA (p < 0.05). Values from real-time RT-PCR analyses were determined using the 2-ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001), which facilitates the analysis of relative changes in gene expression from real-time quantitative RT-PCR experiments.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the USPHS - AA03490.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahlemeyer B, Beier H, Semkova I, Schaper C, Krieglstein J. S-100beta protects cultured neurons against glutamate and staurosporine-induced damage and is involved in the antiapoptotic action of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist. Bay X 3702. Brain Res. 2000;858:121–128. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02438-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt-Jovin DJ, Jovin TM. Analysis and sorting of living cells according to deoxyribonucleic acid content. J Histochem Cytochem. 1977;25:585–589. doi: 10.1177/25.7.70450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia EC, Dolan K, Whitaker-Azmitia PM. S-100B but not NGF, EGF, insulin or calmodulin is a CNS serotonergic growth factor. Brain Res. 1990;516:354–356. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90942-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia EC, Gannon PJ, Kheck NM, Whitaker-Azmitia PM. Cellular localization of the 5-HT1A receptor in primate brain neurons and glial cells. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:35–46. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)80057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonthius DJ, Bonthius NE, Napper RM, Astley SJ, Clarren SK, West JR. Purkinje cell deficits in nonhuman primates following weekly exposure to ethanol during gestation. Teratology. 1996;53:230–236. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199604)53:4<230::AID-TERA5>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ, Torricelli JR, Evege EK, Price PJ. Optimized survival of hippocampal neurons in B27-supplemented Neurobasal, a new serum-free medium combination. J Neurosci Res. 1993;35:567–576. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490350513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Businaro R, Leone S, Fabrizi C, Sorci C, Donato R, Lauro GM, Fumagalli L. S100B protects LAN-5 neuroblastoma cells against Aβ amyloid-induced neurotoxicity via RAGE engagement at low doses but increases Aβ amyloid neurotoxity at high doses. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:897–906. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright MM, Tessmer LL, Smith SM. Ethanol-induced neural crest apoptosis is coincident with their endogenous death, but is mechanistically distinct. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:142–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castoldi AF, Barni S, Randine G, Costa GL, Manzo L. Ethanol selectively interferes with the trophic action of NMDA and carbachol and cultured cerebellar granule neurons undergoing apoptosis. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1998;111:279–289. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheema ZF, West JR, Miranda RC. Ethanol induces Fas/Apo [apoptosis]-1 mRNA and cell suicide in the developing cerebral cortex. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:535–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowen DS, Sowers RS, Manning DR. Activation of a mitrogen-activated protein kinase (ERK2) by the 5-hydroxytryptamine1A receptor is sensitive not only to inhibitors of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, but to an inhibitor of phosphatidylcholine hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22297–23000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveraux QL, Roy N, Stennicke HR, Van Arsdale T, Zhou Q, Srinivasula SM, Alnemri ES, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. IAPs block apoptotic events induced by caspase-8 and cytochrome c by direct inhibition of distinct caspases. EMBO J. 1998;17:2215–23. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato R. S100: a multigenic family of calcium-modulated proteins of the EF-hand type with intracellular and extracellular functional roles. Intl J Biochem Cell Biology. 2001;33:637–668. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downward J. PI 3-kinase, Akt and cell survival. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15:177–82. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druse MJ, Kuo A, Tajuddin N. Effects of in utero ethanol exposure on the developing serotonergic system. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1991;15:678–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druse MJ, Tajuddin NF, Gillespie RA, Dickson E, Atieh M, Pietrzak CA, Le PT. The serotonin-1A agonist ipsapirone prevents ethanol-associated death of total rhombencephalic neurons and prevents the reduction of fetal serotonin neurons. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;15:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druse MJ, Tajuddin NF, Gillespie RA, Le PT. Signaling pathways involved with serotonin1A agonist-mediated neuroprotection against ethanol-induced apoptosis of fetal rhombencephalic neurons. Dev Brain Res. 2005;159:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druse MJ, Tajuddin NF, Gillespie RA, Le PT. The effects of ethanol and the serotonin1A agonist ipsapirone on the expression of the serotonin1A receptor and several antiapoptotic proteins in fetal rhombencephalic neurons. Brain Res. 2006;1092:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunty WC, Chen SY, Zucker RM, Dehart DB, Sulik KK. Selective vulnerability of embryonic cell populations to ethanol-induced apoptosis: implications for alcohol-related birth defects and neurodevelopmental disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1523–1535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen JL, Druse MJ. Potential involvement of S100B in the protective effects of a serotonin-1A agonist on ethanol treated astrocytes. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2001;128:157–164. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen JL, Druse MJ. Astrocyte-mediated trophic support of developing serotonin neurons: effects of ethanol, buspirone, and S100B. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2001;131:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00240-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen JL, Gillespie RA, Druse MJ. Effects of ethanol and 5-HT1A agonists on astroglial S100B. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;139:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnavskoya MN, van Biesen T, Hawe B, Casanos Ramos S, Lefkowitz JR, Raymond JR. Ras-dependent activation of fibroblast mitogen-activated protein kinase by 5-HT1A receptor via a G protein beta gamma-subunit-initiated pathway. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13716–13722. doi: 10.1021/bi961764n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves DS, Lenz G, Karl J, Goncalves CA, Rodnight R. Extracellular S100B protein modulates ERK in astrocyte cultures. Neuroreport. 2000;11:807–809. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200003200-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton MB, Mitchell JJ, Paiva M. Amelioration of ethanol-induced neurotoxicity in the neonatal rat central nervous system by antioxidant therapy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:512–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honegger P, Monnet-Tschudi F. Aggregating neural cell cultures. In: Federoff S, Richardson A, editors. Protocols for Neural Cell Culture. 2nd. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1997. pp. 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen HJ, Fages C, Rauvala H. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE)-mediated neurite outgrowth and activation of NF-κB require the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor but different downstream signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19919–19924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen HJ, Kuja-Panula J, Sorci G, Agneletti AL, Donato R, Rauvala H. Coregulation of neurite outgrowth and cell survival by amphoterin and S100 proteins through receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) activation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40096–40105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006993200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen HJ, Kujua-Panula J, Rauvala H. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) signaling induces CREB-dependent chromagranin expression during neuronal differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38635–38646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidou C, Brittigau P, Ishimaru MJ, Wozniak DF, Koch C, Genz K, Price MT, Stefovska V, Horster F, Tenkova T, Dikranian K, Olney JW. Ethanol-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration and fetal alcohol syndrome. Science. 2000;287:1056–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JS, Miller MW. Proliferation and death of cultured fetal neocortical neurons: effects of ethanol on the dynamics of cell growth. J Neurocytol. 2001;30:391–401. doi: 10.1023/a:1015013609424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JA, Druse MJ. Protective effects of maternal buspirone treatment on serotonin reuptake sites in ethanol-exposed offspring. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;92:190–198. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(96)00015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kögel D, Peters M, König HG, Hashemi SMA, Bui NT, Arolt V, Rothermundt M, Prehn JHM. S100B potently activates p65/c-REl transcriptional complexes in hippocampal neurons: clinical implications for the role of S100B in excitotoxic brain injury. Neuroscience. 2004;127:913–920. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König N, Wilkie MB, Lauder J. Dissection of monoaminergic neuronal groups from embryonic rat brain. In: Sharar A, deVellis J, Vernadakis A, Haber B, editors. A Dissection and Tissue Culture Manual of the Nervous System. Alan R. Liss, Inc.; N.Y.: 1989. pp. 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kucharczak J, Simmons MJ, Fan Y, Gelinas C. To be, or not to be: NF-ΚB is the answer – role of Rel/ NF-ΚB in the regulation of apoptosis. Oncogene. 2003;22:8961–8982. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauder JM, Krebs H. Serotonin as a differentiation signal in early neurogenesis. Dev Neurosci. 1978;1:15–30. doi: 10.1159/000112549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauder JM. Ontogeny of the serotonergic system in the rat: serotonin as a developmental signal. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;600:297–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb16891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam AG, Koppal T, Akama KT, Guo L, Craft JM, Samy B, Schavocky JP, Watterson DM, Van Eldik LJ. Mechanism of glial activation by S100B: involvement of the transcription factor NFκB. Neurobiol Aging. 2001:765–772. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesi P. Ethanol-exposed central neurons fail to migrate and undergo apoptosis. J Neurosci Res. 1997;48:439–448. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19970601)48:5<439::aid-jnr5>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light KE, Belcher SM, Pierce DR. Time course and manner of Purkinje neuron death following a single ethanol exposure on postnatal day 4 in the developing rat. Neuroscience. 2002;114:327–337. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier SE, Miller JA, Blackwell JM, West J. Fetal alcohol exposure and temporal vulnerability: regional differences in cell loss as a function of the timing of binge-like alcohol exposure during brain development. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:726–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1999.tb04176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcussen BL, Goodlett CR, Mahoney JC, West JR. Developing rat Purkinje cells are more vulnerable to alcohol-induced depletion during differentiation than during neurogenesis. Alcohol. 1994;11:147–156. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(94)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Generation of neurons in the rat dentate gyrus and hippocampus: effects of prenatal and postnatal treatment with ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:1500–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulder KL, Fu T, Melbostad H, Cormier RJ, Isenberg KE, Zorumski CF, Mennerick S. Ethanol-induced death of postnatal hippocampal neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;10:396–409. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi M, Kawata M, Azmitia EC. S100B promotes the extension of microtubule associated protein2 (MAP2)-immunoreactive neuritis retracted after colchicines treatment in rat spinal cord culture. Neurosci Lett. 1997;229:212–214. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00443-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran V, Perez A, Chen J, Senthil D, Schenker S, Henderson GI. In utero ethanol exposure causes mitochondrial dysfunction, which can result in apoptotic cell death in fetal brain: a potential role for 4-hydroxynonenal. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:862–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathbun W, Druse MJ. Dopamine, serotonin and acid metabolites in brain regions from the developing offspring of ethanol treated rats. J Neurochem. 1985;44:57–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb07112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy N, Devereaux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. The c-IAP-1 and c-IAP-2 proteins are direct inhibitors of specific caspases. EMBO J. 1997;16:6914–6925. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sari Y, Zhou FC. Prenatal alcohol exposure causes long-term serotonin neuron deficit in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:941–948. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128228.08472.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorci G, Riuzzi F, Agneletti AL, Marchetti C, Donato R. S100B causes apoptosis in a myoblast cell line in a RAGE-independent manner. J Cell Physiol. 2004;199:274–283. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajuddin NF, Druse MJ. Treatment of pregnant alcohol-consuming rats with buspirone: effects on serotonin and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid content in offspring. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:110–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajuddin NF, Druse MJ. In utero ethanol exposure decreased the density of serotonin neurons. Maternal ipsapirone treatment exerted a protective effect. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;117:91–97. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajuddin NF, Druse MJ. A persistent deficit of serotonin neurons in the offspring of ethanol-fed dams: Protective effects of maternal ipsapirone treatment. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2001;129:181–188. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eldik LJ, Christie-Pope B, Bolin LM, Shooter EM, Whetsell WO. Neurotrophic activity of S-100beta in cultures of dorsal root ganglia from embryonic chick and fetal rat. Brain Res. 1991;542:280–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91579-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker-Azmitia PM, Murphy R, Azmitia EC. Stimulation of astroglial 5-HT1A receptors releases the serotonergic growth factor, protein S-100, and alters astroglial morphology. Brain Res. 1990;528:155–158. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker-Azmitia PM, Druse M, Walker P, Lauder JM. Serotonin as a developmental signal. Behav Brain Res. 1996;73:19–29. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FC, Sari Y, Zhang JK, Goodlett CR, Li T. Prenatal alcohol exposure retards the migration and development of serotonin neurons in fetal C57BL mice. Dev Brain Res. 2001;125:147–155. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(00)00144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]