Abstract

Background

On 4 October 1992, a cargo aircraft crashed into apartment buildings in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Fire‐fighters and police officers assisted with the rescue work.

Objectives

To examine the long term health complaints in rescue workers exposed to a disaster.

Methods

A historical cohort study was performed among police officers (n = 834) and fire‐fighters (n = 334) who performed at least one disaster related task and reference groups of their non‐exposed colleagues (n = 634 and n = 194, respectively). The main outcome measures included digestive, cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, nervous system, airway, skin, post‐traumatic stress, fatigue, and general mental health complaints; haematological and biochemical laboratory values; and urinalysis outcomes.

Results

Police officers and fire‐fighters who were professionally exposed to a disaster reported more physical and mental health complaints, compared to the reference groups. No clinically relevant statistically significant differences in laboratory outcomes were found.

Conclusions

This study is the first to examine long term health complaints in a large sample of rescue workers exposed to a disaster in comparison to reference groups of non‐exposed colleagues. Findings show that even in the long term, and in the absence of laboratory abnormalities, rescue workers report more health complaints.

Keywords: health effects, long‐term, disaster, rescue workers, ESADA

On 4 October 1992, a cargo aircraft crashed into two apartment buildings in a densely populated suburb of Amsterdam, the capital of the Netherlands. The Amsterdam Air Disaster resulted in 39 fatal injuries on the ground, killed all four occupants of the aircraft, and destroyed 266 apartments. Fire‐fighters and police officers helped to rescue the victims of this disaster, to extinguish the fire, and to clear away the debris.

Several years later, some of the police officers and fire‐fighters who had been exposed to the disaster, and a number of inhabitants of the area were still worried about the content of the cargo of the aircraft. They reported a variety of health complaints, which they attributed to the disaster, and called for a study to investigate whether their health complaints were related to the disaster. In 1998, a parliamentary inquiry was held to investigate the cause of the crash and to gain insight into the content of the cargo of the aircraft. One of the recommendations was that an epidemiological study should be conducted to investigate the health status of the victims of the disaster and the rescue workers exposed to the disaster.

The Amsterdam Air Disaster is an example of a technological disaster with a sudden onset. Other studies have shown that such disasters may result in acute injuries (such as burns and fractures) and short term symptoms (such as respiratory symptoms).1 However, the mere threat of exposure to hazardous material during such an event may also be a source of stress, associated with changes in mental health, physical health, and health related behaviour.2 Indeed, various symptoms, such as headache, fatigue, memory disorders, joint and muscle aches, bowel symptoms, dizziness, anxiety, depression, and post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have sometimes been found to develop over time among affected populations after various disastrous events.3,4,5,6 Moreover, the long aftermath of the Amsterdam Air Disaster and the confusing and ambiguous information in the media may have been an additional cause of distress to those involved. In fact, the disaster was followed by speculation regarding the content of the cargo of the plane, that might have included a toxic agent (such as depleted uranium, mycoplasma fermentans, sarin), rumours, and conspiracy theories.7,8 According to Vasterman et al,7 two media hypes were reinforced, which concerned the presumed “cover‐up” about an unknown toxic agent that may cause health symptoms. These media hypes were followed by new groups of people who reported suffering from health problems which they attributed to the disaster.7

Most of the previous studies have focused on the health status of inhabitants of the affected area of a disaster and reported short term health complaints only. Furthermore, very few studies included a reference group of people who were not exposed to the disaster, and information on disaster related long term health complaints in rescue workers is scarce. The present large scale historical cohort study was designed to study the long term health complaints in police officers and fire‐fighters exposed to a disaster.

Our aim was to investigate the physical and mental health status of police officers and fire‐fighters 8.5 years after they had been exposed to the Amsterdam Air Disaster and to compare their health status with that of colleagues in reference groups.

Methods

Participants

All police officers and fire‐fighters who were on active duty at the time of the disaster and in the weeks afterwards, were invited to participate in the Epidemiological Study Air Disaster Amsterdam (ESADA) study. Due to administrative deficiencies and partial lack of historic registration of exposure status, we used detailed self‐reported data to define exposure status for all workers. Therefore, our study can be regarded as a historic cohort study, with retrospective data on exposure.

Participants completed a questionnaire on professional exposure to the disaster, which included questions on disaster related tasks such as “saving people's lives”, “extinguishing the fires”, and “transporting the wounded”. Police officers and fire‐fighters who performed at least one task, were defined as being “exposed”. Police officers were mostly involved in security tasks (surveillance, preventing burglary, keeping disaster area free of bystanders), a variety of other tasks (including traffic management), and assisting or providing first aid to injured victims or emergency personnel. The most prevalent tasks among fire‐fighters were fire extinguishing, rescuing people, and clearing up of the destructed area. We have used a priori stratification by occupational group, because of fundamental differences between these occupational groups (i.e. police officers and fire‐fighters) with respect to occupational exposure to the disaster, general health status, and sociodemographic variables.

Professional colleagues who did not perform any disaster related task were also invited to participate in the study, in “non‐exposed” reference groups, and were matched according to job title. The exclusion criteria were: having insufficient knowledge of the Dutch language and therefore not being able to fill in questionnaires, residing in the disaster area, and missing questionnaire data on disaster related tasks.

All of the participants gave written informed consent and participated voluntarily. Data were collected in an outpatient clinic of the Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis (OLVG) in Amsterdam, which took place from January 2000 to March 2002, on average 8.5 years after the Amsterdam Air Disaster. Details of the history and the set‐up of the study, including details about the outcome measures, have been reported elsewhere.9

Health outcomes (perceived health complaints)

All participants filled out questionnaires on their current health status at the time of the assessment.

The International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC), as designated by the World Organization for Family Doctors (WONCA), was used to classify the symptoms reported by the participants.10 The following somatic symptoms categories were used in the analysis: (1) general and non‐specific, (2) digestive system, (3) cardiovascular system, (4) musculoskeletal system, (5) nervous system, (6) respiratory tract, and (7) skin. A dichotomised score was composed for each category of symptoms (0 = no symptoms, 1 = at least one symptom in this category).

Post‐traumatic stress symptoms were assessed using the Self‐Rating Inventory for Post‐traumatic Stress Disorder (SRIP), a 22 item questionnaire.11,12,13 The items were based on symptoms of post‐traumatic stress disorder as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐IV) for psychiatric diagnoses.14 A cut‐off score of 39 was predetermined to define individuals who have problems due to involvement in a traumatic event.15

Fatigue symptoms were measured with the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS), a 20 item scale, resulting in four subscales and a total score. For the present study, use was made of dichotomised scores on the “subjective fatigue” subscale (cut‐off score: 35) and the total score (cut‐off score: 76).16,17

General mental health was assessed by means of the Symptom Checklist (SCL‐90).18 This is a 90 item questionnaire, which consists of eight subscales (somatic symptoms, depression, anxiety, obsessive‐compulsive behaviour, agoraphobia, interpersonal sensitivity, hostility, sleeping problems). Scores above the 65th centile of the normal Dutch population were regarded as deviant.19

Laboratory outcomes

All the laboratories involved in this study carried out their analyses according to the accredited (Dutch) standards. We used the clinical cut‐off values of these laboratories to define a deviant outcome.20 The blood count included haemoglobin, leucocyte count, differential leucocyte count, and platelet count. Blood chemical values included potassium, creatinine, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, gamma‐glutamyl transferase, creatine kinase, thyroid stimulating hormone, C reactive protein, and ferritin. Urinalysis included the dipstick test followed by microscopic evaluation of the urinary sediment if indicated by presence of protein.

Statistical analysis

Differences between the exposed police officers and fire‐fighters and their reference groups were analysed with unconditional multiple logistic regression analyses. All analyses were adjusted for the following potential confounders: age, professional level, level of education, alcohol consumption, smoking habits, and level of physical activity. For police officers only, gender and ethnicity were added as potential confounders. In addition, mental health outcomes were adjusted for the number of adverse pre‐disaster life events and the presence of chronic diseases. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated. The analyses were carried out in SPSS version 10.1; p < 0.05 (two sided) was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

Response

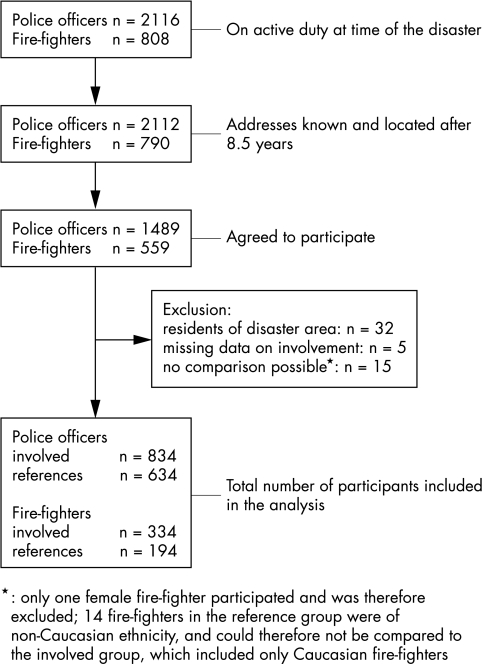

The response from both the police officers and the fire‐fighters was 70%. Of the 2112 police officers who were invited to participate, 1489 agreed. After the exclusion criteria had been applied, data from 834 exposed police officers and 634 non‐exposed police officers were analysed. Of the 790 fire‐fighters who were invited to participate, 559 agreed, and after the exclusion criteria had been applied, data from 334 exposed and 194 non‐exposed fire‐fighters were analysed. Details are shown in fig 1. Table 1 presents background characteristics of the participants.

Figure 1 Flow chart of the response.

Table 1 Background characteristics of the participants.

| Police officers | Fire‐fighters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed | Reference | Exposed | Reference | |

| n | 834 | 634 | 334 | 194 |

| Age in years (SD) | 44.0 (6.2) | 44.8 (7.0) | 51.4 (5.9) | 38.8 (9.1) |

| Level of education (%) | ||||

| Low | 22.0 | 20.9 | 63.4 | 52.7 |

| Intermediate | 55.8 | 54.3 | 29.8 | 36.6 |

| High | 22.2 | 24.8 | 6.8 | 10.8 |

| Alcohol consumption* (%) | ||||

| None | 11.4 | 8.2 | 4.2 | 12.4 |

| Low to moderate | 74.3 | 75.7 | 72.8 | 70.6 |

| Heavy | 14.3 | 16.1 | 23.1 | 17.0 |

| Smoking habits (%) | ||||

| None | 33.1 | 27.9 | 32.0 | 44.8 |

| Former smoker | 31.7 | 38.0 | 35.0 | 29.4 |

| Current smoker | 35.3 | 34.1 | 32.9 | 25.8 |

| Male gender (%) | 88.5 | 84.9 | 100 | 100 |

SD, standard deviation.

*Alcohol consumption was assessed according to the Garretsen index.50

We attempted to contact a random sample of non‐respondent fire‐fighters (n = 66 (29%) of n = 231) by telephone for a brief interview. Of this sample, 47 (71%) completed the interview. Only five were unwilling to participate, while 14 non‐respondents could not be contacted, even after several attempts. Non‐respondents and participants were compared with respect to sociodemographic variables (age, sex, level of education), and subjective health outcomes (general health; physical symptoms; psychological symptoms; chronic skin, joint, or respiratory diseases since 1992). For most of these variables, no statistically significant differences between non‐respondents and participants were found. However, compared to their participating counterparts, non‐respondent fire‐fighters were slightly older, reported less often a low level of education, and more often had psychological complaints and chronic arthritis since the year of the disaster (1992).

Perceived health complaints

Table 2 presents the results of the multiple logistic regression analyses with regard to the ICPC symptom categories, adjusted for potential confounders. In general, the exposed police officers and the exposed fire‐fighters reported health complaints significantly more often than the respective reference group.

Table 2 Comparison between exposed police officers and fire‐fighters and their reference groups with regard to health complaints, subdivided into ICPC symptom categories.

| ICPC symptom categories | Police officers | Fire‐fighters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed | Reference | OR | (95% CI) | Exposed | Reference | OR | (95% CI) | |

| General/non‐specific | 40.4% | 27.4% | 1.92 | (1.52–2.41)* | 32.1% | 16.0% | 2.00 | (1.12–3.58)* |

| Digestive | 21.3% | 15.1% | 1.57 | (1.19–2.08)* | 21.3% | 13.4% | 1.84 | (0.95–3.55) |

| Cardiovascular | 25.7% | 16.7% | 1.76 | (1.35–2.29)* | 28.7% | 11.3% | 3.30 | (1.70–6.41)* |

| Musculoskeletal | 42.1% | 29.2% | 1.86 | (1.49–2.33)* | 53.9% | 25.8% | 2.56 | (1.55–4.23)* |

| Nervous system | 51.1% | 39.7% | 1.66 | (1.34–2.06)* | 49.2% | 28.4% | 2.87 | (1.71–4.81)* |

| Airway | 29.7% | 19.7% | 1.80 | (1.40–2.32)* | 29.9% | 12.9% | 1.67 | (0.92–3.03) |

| Skin | 51.9% | 28.4% | 2.78 | (2.21–3.48)* | 54.8% | 32.5% | 3.37 | (2.01–5.62)* |

ICPC, International Classification of Primary Care; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

*p<0.05.

Table 3 presents the results of the multiple logistic regression analyses with regard to mental health outcomes, adjusted for potential confounders. In general, the exposed police officers reported symptoms significantly more often than the reference group, including PTSD, fatigue, and indices of psychopathology. The exposed fire‐fighters reported significantly more fatigue and somatic symptoms than the reference group.

Table 3 Comparison between exposed police officers and fire‐fighters and their reference groups with regard to mental health complaints.

| Police officers | Fire‐fighters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed | Reference | OR (95% CI) | Exposed | Reference | OR (95% CI) | |

| PTSD (SRIP) | 6.5% | 2.4% | 2.8 (1.5–5.0)* | 5.4% | 2.6% | 1.1 (0.4–3.7) |

| Fatigue (CIS) | ||||||

| Subjective fatigue | 19.4% | 9.9% | 2.0 (1.4–2.7)* | 11.7% | 5.2% | 2.5 (1.0–6.6)* |

| Total score | 16.7% | 8.8% | 1.8 (1.3–2.6)* | 11.7% | 2.6% | 3.6 (1.2–11.0)* |

| SCL‐90 | ||||||

| Agoraphobia | 8.3% | 6.3% | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) | 9.6% | 4.1% | 1.9 (0.5–3.0) |

| Anxiety | 31.7% | 18.9% | 1.8 (1.4–2.3)* | 27.2% | 20.6% | 1.2 (0.7–2.5) |

| Depression | 21.9% | 11.4% | 2.1 (1.5–2.8)* | 20.1% | 8.2% | 1.6 (0.8–3.1) |

| Somatic symptoms | 32.4% | 17.0% | 2.1 (1.6–2.7)* | 34.4% | 13.9% | 2.6 (1.4–4.8)* |

| Obsessive‐compulsive | 26.9% | 16.7% | 1.7 (1.3–2.2)* | 28.1% | 12.9% | 1.8 (1.0–3.2)* |

| Inter‐personal sensitivity | 12.0% | 7.7% | 1.5 (1.1–2.2)* | 13.5% | 6.7% | 1.5 (0.7–3.3) |

| Hostility | 42.7% | 32.2% | 1.5 (1.2–1.8)* | 34.7% | 24.2% | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) |

| Sleeping problems | 48.3% | 35.5% | 1.6 (1.3–2.0)* | 47.9% | 32.0% | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PTSD, post‐traumatic stress disorder; SRIP, Self‐Rating Inventory for Post‐traumatic Stress Disorder; CIS, Checklist Individual Strength; SCL‐90, Symptoms Checklist‐90.

*p<0.05.

The reported prevalences reflect scores above the cut‐off values for the questionnaires. Analyses are adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, professional level, level of education, alcohol consumption, smoking habits, level of physical activity, number of adverse life events, and chronic diseases.

The percentages reflect the relative number of participants who reported one or more symptom(s) in the relevant symptoms categories. Analyses are adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, professional level, level of education, alcohol consumption, smoking habits, and level of physical activity.

Laboratory outcomes

The laboratory analyses (table 4) showed no significant differences between exposed participants and their respective reference groups. There were two exceptions. In exposed fire‐fighters the number of leucocytes was less frequently increased than in non‐exposed fire‐fighters. As an increase in the number of leucocytes could indicate disease in the reference group, this finding would be in favour of the exposed group. Furthermore, in exposed police officers, a significant larger group of participants with a (slightly) increased percentage of monocytes was found. However, the increased percentage of monocytes did not exceed 15% of the differential count (data not shown).

Table 4 Comparison between exposed police officers and fire‐fighters and their reference groups with regard to laboratory outcomes.

| Police officers | Fire‐fighters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed | Reference | OR (95% CI) | Exposed | Reference | OR (95% CI) | |

| Blood count | ||||||

| Haemoglobin | ||||||

| % decreased | 14.5% | 17.1% | 0.9 (0.6–1.1) | 14.4% | 25.3% | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) |

| Leucocytes | ||||||

| % increased | 5.5% | 4.9% | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) | 3.0% | 3.6% | 0.2 (0.05–0.7)* |

| % decreased | 0.2% | 0.2% | – | 0.0% | 0.5% | – |

| Neutrophils | ||||||

| % increased | 1.0% | 1.0% | 1.0 (0.3–3.0) | 0.9% | 1.0% | – |

| % decreased | 2.8% | 2.4% | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) | 2.4% | 2.1% | – |

| Lymphocytes | ||||||

| % increased | 15.0% | 14.5% | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) | 12.9% | 16.0% | 0.8 (0.4–1.5) |

| % decreased | 10.0% | 8.7% | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 12.9% | 7.2% | 1.2 (0.6–2.7) |

| Monocytes | ||||||

| % increased | 9.7% | 6.3% | 1.6 (1.1–2.4)* | 11.7% | 8.2% | 2.3 (1.0–5.5)* |

| % decreased | 0.2% | 0.2% | – | 0.3% | 0.0% | – |

| Eosinophils | ||||||

| % increased | 8.2% | 7.0% | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 5.7% | 8.8% | 0.5 (0.2–1.3) |

| Basophils | ||||||

| % increased | 0.0% | 0.0% | – | 0.0% | 0.0% | – |

| Platelet count | ||||||

| % increased | 0.7% | 0.9% | 0.8 (0.3–2.6) | 0.3% | 1.0% | – |

| % decreased | 1.7% | 1.4% | 1.3 (0.6–3.0) | 1.8% | 1.0% | – |

| Blood chemical values | ||||||

| Potassium | 15.2% | 18.5% | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 15.1% | 14.5% | 1.4 (0.7–2.8) |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 10.8% | 8.2% | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) | 6.9% | 3.6% | 0.9 (0.3–2.7) |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 0.5% | 0.5% | – | 0.3% | 2.1% | – |

| Gamma‐glutamyl transferase | 14.1% | 13.6% | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 16.2% | 7.7% | 0.9 (0.4–1.8) |

| Creatine kinase | 17.9% | 17.9% | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 23.4% | 38.3% | 1.1 (0.7–2.0) |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone | ||||||

| % increased | 1.1% | 1.0% | 1.4 (0.5–3.9) | 1.2% | 1.0% | – |

| % decreased | 1.0% | 0.6% | – | 0.9% | 0.0% | – |

| C reactive protein | 3.7% | 3.2% | 1.2 (0.7–2.2) | 3.9% | 3.1% | 0.5 (0.1–1.7) |

| Ferritin | 12.5% | 12.3% | 1.0 (0.8–1.5) | 21.0% | 7.2% | 1.7 (0.8–3.4) |

| Urinalysis | ||||||

| Creatinine clearance | ||||||

| % decreased | 0.1% | 0.5% | – | 1.2% | 0.5% | – |

| Proteinuria with either sediment abnormality or increased serum creatinine | 4.4% | 4.0% | 1.2 (0.7–2.0) | 2.7% | 2.6% | 1.5 (0.3–7.2) |

*p<0.05.

–, analyses were not performed due to the very low number of cases (n<5).

The reported prevalences reflect scores above (increased) or below (decreased) the cut‐off values for parameters. Cut‐off values: haemoglobin: men <8.7 mmol/l, women <7.5 mmol/l; leucocyte count <3×109/l or >10×109/l; differential leucocyte count: neutrophils <45% or >80%, lymphocytes <20% or >35%, monocytes <2% or >10%, eosinophils >5%, and basophils >2%; platelet count <150×109/l or >400×109/l; potassium <3.6 mmol/l; creatinine: men >115 μmol/l, women 95 μmol/l; alanine aminotransferase >45 U/l; alkaline phosphatase >120 U/l; gamma‐glutamyl transferase: men >50 U/l, women >35 U/l; creatine kinase: men >190 U/l, women 170 U/l; thyroid stimulating hormone <0.4 IU/l or >4 IU/l; C reactive protein >10 mg/l; ferritin >250 ng/ml; urinalysis: creatinine clearance: Cockroft equation ((140−age)×body weight)/((creatinine (serum))×0.86 (males) or ×1.01 (females)) was used to estimate clearance of endogenous creatinine, cut‐off: <75 ml/min. Proteinuria with either sediment abnormality or increased serum creatinine, cut‐off: protein not negative, erythrocytes >5 per high power field, leucocytes >10 per high power field, bacteria not negative. Analyses are adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, professional level, level of education, alcohol consumption, smoking habits, and level of physical activity.

Discussion

Our study is the first to examine long term health complaints of rescue workers exposed to a disaster in comparison to reference groups of non‐exposed colleagues. In this historical cohort study we had the unique opportunity to compare the health status of exposed police officers and fire‐fighters with that of a reference group of non‐exposed colleagues, 8.5 years after the Amsterdam Air Disaster. Self‐reported health complaints were compared, as well as routine laboratory analyses of urine and blood. The results showed that, even after 8.5 years, the police officers and fire‐fighters who were professionally exposed to the disaster reported health complaints significantly more often than their colleagues in the reference groups. This difference concerned cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, nervous system, skin, and fatigue complaints for the exposed police officers as well as the exposed fire‐fighters, and airway, digestive, and general physical and mental health complaints for the exposed police officers only. Laboratory analyses showed no statistically significant or clinically relevant differences between the exposed participants and their reference groups. Thus, we found no indication that the excess number of complaints in the exposed workers could be accounted for by any somatic disease, in particular haematological, chronic infectious, immunological, kidney, liver, or thyroid diseases. The only laboratory outcome that could have clinical relevance (more frequently an increased number of leucocytes in non‐exposed fire‐fighters) is not an indication for disease in the exposed group, but, on the contrary, it is in favour of the exposed group.

The results of this study are highly relevant for future research on health complaints in rescue workers following disasters. For instance, recent studies have shown that rescue workers who were exposed to the World Trade Center disaster in New York reported symptoms of ill health in the short term.21,22 In fact, most previous studies on the health complaints of disasters have focused on shorter term effects in direct victims, e.g. the inhabitants of an area that was struck by a flood23 or a bush fire.24,25 In general, these studies reported an increase in various health problems in natural disaster victims, compared to controls. A higher frequency of relatively minor physical symptoms rather than clinically relevant pathology, was reported in most studies.26 However, in these studies a broad range of methods was used to assess the physical consequences of the disaster, and they varied in the number of participants, and in the follow up duration after the disaster. For instance, several studies were based on small samples, and covered only a short period of time after the disaster, which is likely to result in a high incidence of temporary morbidity. Two studies compared self‐report data on health before and after a disaster, because the disaster took place between the assessment waves of ongoing panel studies,27,28 and found that exposure to a flood accounted for 2–12% of the change in physical health status across the measurement intervals, but was not related to the onset of clinically relevant disorders.

In addition to natural disasters, several chemical and radiation disasters have taken place since 1980, including the Chernobyl disaster, the Three Miles Island incident, and other, smaller incidents in which inhabitants and rescue workers were exposed to potential hazardous materials.29,30,31 In some cases, exposure to the hazardous materials was reported to be a plausible cause for the negative health complaints that were found, while in others it was suggested that the insecurity, loss of control, and risk perception may have accounted for the reported health complaints.29,32 This may have played a role in the Amsterdam Air Disaster as well, since the crash was followed by a long aftermath, with increased risk perception, and confusing and ambiguous information about the cargo contents.7,8 Another explanation for our findings may be that exposed disaster workers were more likely to interpret certain physical sensations as symptoms of adverse health, which they attributed to the disaster. Media reports on individual cases with multiple symptoms may have enhanced this tendency. These media reports focused on all sorts of toxic agents that might have been present in the cargo of the crashed plane.7 Such news can increase fear and anxiety among those involved in disasters,7,33 and may have increased the attribution of health complaints to exposure to the disaster. General practitioners, however, associated only a small proportion of the reported symptoms with the disaster in a sample of patients in Amsterdam.34 The symptoms reported in the present study were all based on self‐report, and could not be confirmed by laboratory measures. It is possible that the phenomenon commonly described as “unexplained physical symptoms”, i.e. physical symptoms without sufficient objective, demonstrable pathological abnormalities, is therefore applicable to our findings.35 A recent review stated that these unexplained symptoms are common in survivors of disasters.35 However, we cannot rule out the possibility that there is a biological marker for these complaints, albeit one that is not (yet) known. Fear of exposure may also have played a role in the self‐reported complaints, because some researchers have suggested that insecurity, loss of control, and risk perception after exposure to hazardous materials may account for reported adverse health.29,32,36,37,38,39,40

Only a few studies have specifically focused on the health status of rescue workers, such as police officers and fire‐fighters. Although rescue workers are usually not direct victims of a disaster, their duties may include exposure to very stressful and traumatic events, such as the salvage and identification of bodies, rescue work under high risk conditions with fear for their physical integrity, and even for their own lives, and contact with the bereaved families. Post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) could also play a role in the assessment of physical health complaints of disaster exposure, as there is a large body of literature on the co‐occurrence of PTSD and adverse physical health outcomes after traumatic events.39 Several studies have shown that rescue workers are at risk for post‐traumatic stress disorders.40,41,42,43,44 Other mental health complaints have also been found, including sleeping problems,45 and anxiety or depression.46,47 In contrast, however, several studies have shown that rescue workers may be regarded as a highly resilient group of professionals with regard to the potentially harmful effects of stress.42,48,49

A few limitations of the present study should be mentioned. First, there is a considerable time lag between the disaster and the start of our study, i.e. on average 8.5 years. Therefore, we were not able to study the exact timing of onset of the reported complaints, nor were we able to analyse the course of the complaints during this period of time. Prospective longitudinal studies are needed to gain insight into the timing of onset and the course of complaints after a disaster. A further limitation of our study is the fact that non‐exposed workers were younger than the exposed fire‐fighters. Because almost the entire fire department was involved in the disaster related work, this was unavoidable. Therefore, non‐exposed fire‐fighters who joined this fire department after the disaster were included in the reference group. The applied statistical adjustments for age and other potentially related confounders may not have fully accounted for this systematic difference between exposed and non‐exposed fire‐fighters.

The results of the present study demonstrate that police officers and fire‐fighters exposed to the Amsterdam Air Disaster reported a broad range of health complaints more than eight years after the disaster, similar to what is sometimes found for victims of natural or technological disasters.3,4,5,6 However, the symptoms of our participants were all based on self‐report, and could not be confirmed by routine laboratory tests. The outcomes of laboratory tests show no morbidity in relation to the disaster. In addition, no difference in absence at work due to illness was found between the exposed police officers and fire‐fighters and the reference groups (data not shown). These findings suggest that there is no serious somatic pathological condition underlying the self‐reported symptoms.

Footnotes

Funding: the study was funded by the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports, the City of Amsterdam, the regional police force Amsterdam‐Amstelland, and KLM Royal Dutch Airlines

Competing interests: none

References

- 1.McFarlane A C, Atchison M, Rafalowicz E.et al Physical symptoms in post‐traumatic stress disorder. J Psychosom Res 199438715–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Havenaar J M, van den Brink W. Psychological factors affecting health after toxicological disasters. Clin Psychol Rev 199717359–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Escobar J I, Canino G, Rubio‐Stipec M.et al Somatic symptoms after a natural disaster: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry 1992149965–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engel C C., Jr Outbreaks of medically unexplained physical symptoms after military action, terrorist threat, or technological disaster. Mil Med 200116647–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barsky A J, Borus J F. Functional somatic syndromes. Ann Intern Med 1999130910–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wessely S. Ten years on: what do we know about the Gulf War syndrome? King's College Gulf War Research Unit. Clin Med 2001128–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasterman P, Yzermans C J, Dirkzwager A J E. The role of the media and media hypes in the aftermath of disasters. Epidemiol Rev 200527107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yzermans C J, Gersons B P, Havenaar J M, Cwikel J G, Bromet E J. The chaotic aftermath of an airplane crash in Amsterdam: a second disaster. In: eds. Toxic turmoil: psychological and societal consequences of ecological disasters. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 200285–99.

- 9.Slottje P, Huizink A C, Twisk J W.et al Epidemiological study air disaster in Amsterdam (ESADA): study design. BMC Public Health 2005554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamberts H, Wood M. eds. ICPC: International Classification of Primary Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987

- 11.Hovens J E, Bramsen I, van der Ploeg H M. Self‐rating inventory for posttraumatic stress disorder: review of the psychometric properties of a new brief Dutch screening instrument. Percept Mot Skills 200294996–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hovens J E, van der Ploeg H M, Bramsen I.et al Test‐retest reliability of the self‐rating inventory for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Rep 200087735–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hovens J E, van der Ploeg H M, Bramsen I.et al The development of the Self‐Rating Inventory for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 199490172–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐IV), 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association 1994

- 15.van Zelst W H, de Beurs E, Beekman A T.et al Criterion validity of the self‐rating inventory for posttraumatic stress disorder (SRIP) in the community of older adults. J Affect Disord 200376229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bultmann U, de Vries M, Beurskens A J.et al Measurement of prolonged fatigue in the working population: determination of a cutoff point for the checklist individual strength. J Occup Health Psychol 20005411–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vercoulen J H M, Alberts M, Bleijenberg G. De Checklist Individual Strength (CIS). Kort instrumenteel [The Checklist Individual Strength (CIS)]. Gedragstherapie 1999131–136.

- 18.Derogatis L R, Lipman R S, Covi L. SCL‐90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale—preliminary report. Psychopharmacol Bull 1973913–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arrindell W A, Ettema J H M.Handleiding bij een multidimensionele psycho‐pathologie indicator [Manual for a multi‐dimensional indicator of psychopathology]. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger, 1986

- 20.Diagnostisch Kompas [Diagnostic Kompass] College voor Zorgverzekeringen 2004

- 21.Feldman D M, Baron S L, Bernard B P.et al Symptoms, respirator use, and pulmonary function changes among New York City firefighters responding to the World Trade Center disaster. Chest 20041251256–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Center of Disease Control and Prevention Potential exposures to airborne and settled surface dust in residential areas of lower Manhattan following the collapse of the World Trade Center, New York City, November 4–December 11, 2001. JAMA 200361498–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennet G. Bristol floods 1968. Controlled survey of effects on health of local community disaster. BMJ 19703454–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valent P. The Ash Wednesday bushfires in Victoria. Med J Aust 1984141291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clayer J R, Bookless‐Pratz C, Harris R L. Some health consequences of a natural disaster. Med J Aust 1985143182–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hovanitz C A. Physical health risks associated with aftermath of disaster: basic paths of influence and their implications for preventative intervention. Journal of Social Behaviour and Personality 19938213–254. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phifer J F. Psychological distress and somatic symptoms after natural disaster: differential vulnerability among older adults. Psychol Aging 19905412–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phifer J F, Kaniasty K Z, Norris F H. The impact of natural disaster on the health of older adults: a multiwave prospective study. J Health Soc Behav 19882965–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landauer M R, Young R W, Hawley A L. Physiological and psychological impact of low‐level radiation: an overview. Mil Med 2002167141–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baum A, Fleming I. Implications of psychological research on stress and technological accidents. Am Psychol 199348665–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dew M A, Bromet E J. Predictors of temporal patterns of psychiatric distress during 10 years following the nuclear accident at Three Mile Island. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 19932849–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Havenaar J M, de Wilde E J, van den Bout J.et al Perception of risk and subjective health among victims of the Chernobyl disaster. Soc Sci Med 200356569–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petrie K J, Broadbent E A, Kley N.et al Worries about modernity predict symptom complaints after environmental pesticide spraying. Psychosomat Med 200567778–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donker G A, Yzermans C J, Spreeuwenberg P.et al Symptom attribution after a plane crash: comparison between self‐reported symptoms and GP records. Br J Gen Pract 200252917–922. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van den Berg B, Grievink L, Yzermans J.et al Medically unexplained physical symptoms in the aftermath of disasters. Epidemiol Rev 20052792–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koscheyev V S, Leon G R, Gourine A V.et al The psychosocial aftermath of the Chernobyl disaster in an area of relatively low contamination. Prehospital Disaster Med 19971241–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collins D L, de Carvalho A B. Chronic stress from the Goiania 137Cs radiation accident. Behav Med 199318149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clauw D J, Engel C C, Aronowitz R.et al Unexplained symptoms after terrorism and war: an expert consensus statement. J Occup Environ Med 2003451040–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Psychological Association Trauma and health. Physical health consequences of exposure to extreme stress. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2004

- 40.Renck B, Weisaeth L, Skarbo S. Stress reactions in police officers after a disaster rescue operation. Nord J Psychiatry 2002567–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang C M, Lee L C, Connor K M.et al Posttraumatic distress and coping strategies among rescue workers after an earthquake. J Nerv Ment Dis 2003191391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.North C S, Tivis L, McMillen J C.et al Psychiatric disorders in rescue workers after the Oklahoma City bombing. Am J Psychiatry 2002159857–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McFarlane A C. The longitudinal course of posttraumatic morbidity. The range of outcomes and their predictors. J Nerv Ment Dis 198817630–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersen H S. Post‐traumatic stress reactions amongst rescue workers after a major rail accident. Anxiety Research 19914245–251. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neylan T C, Metzler T J, Best S R.et al Critical incident exposure and sleep quality in police officers. Psychosom Med 200264345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sims A, Sims D. The phenomenology of post‐traumatic stress disorder. A symptomatic study of 70 victims of psychological trauma. Psychopathology 19983196–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fullerton C S, Ursano R J, Wang L. Acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in disaster or rescue workers. Am J Psychiatry 20041611370–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ersland S, Weisaeth L, Sund A. The stress upon rescuers involved in an oil rig disaster. “Alexander L. Kielland” 1980. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 198935538–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alexander D A, Wells A. Reactions of police officers to body‐handling after a major disaster. A before‐and‐after comparison. Br J Psychiatry 1991159547–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garretsen H F.Probleemdrinken [Problematic alcohol use]. Lisse: Swets and Zeitlinger, 1983