Abstract

The proximal and distal effects of adversity on the onset of symptoms of substance dependence during adolescence were explored in two culturally distinct American Indian (AI) reservation communities (Northern Plains and Southwest). Data (N=3,084) were from the American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project (AI-SUPERPFP). The age-related risk of symptom onset increased gradually from age 11 through age 16, remained relatively high through age 18, then declined rapidly. Both tribe and gender were related to onset of dependence symptoms; men and Northern Plains tribal members were at greatest risk and Southwest women were at particularly low risk of symptom onset across adolescence. For all tribe and gender groups, both proximal and cumulative distal experiences of adversity were associated with substantially increased risk of symptom onset. The relationship of adversity to onset of substance dependence symptoms remained strong when previous symptoms of psychiatric disorder and childhood conduct problems were considered. These findings suggest that efforts to help children and adolescents in AI communities develop constructive mechanisms for coping with adversity may be especially valuable in substance dependence prevention.

Keywords: substance dependence, American Indians, adversity, trauma, life events

1. Introduction

Epidemiological evidence suggests that substance dependence is significantly more common among American Indian and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs, the indigenous peoples of the continental United States) than among other ethnic populations within the United States (Beals et al., 2003b; Beauvais, 1996; King et al., 1992; Kunitz et al., 1999; Kunitz and Levy, 1994; May, 1995, 1996; Robin et al., 1998; Spicer et al., 2003; Whitesell et al., 2006). Our own work in American Indian (AI) communities has demonstrated significant disparities in rates of dependence, not only between AIs and the United Statespopulation as a whole, but between AI tribal communities as well (Beals et al., 2005a; Beals et al., 2005b; Beals et al., 2003b; O’Connell et al., 2005; Spicer et al., 2003; Whitesell et al., 2006; Whitesell et al., in press). The reduction of such disparities is an important part of the United States public health agenda. Unfortunately, we know more about what disparities exist than we do about why they exist, and thus we are not well poised to design programs that will significantly reduce these disparities. The design of such programs depends on research into the underlying causes of disparities and the identification of intervention strategies clearly related to these causes (SAMHSA, 2001).

One factor that has been postulated to play a causal role in the high rates of substance dependence among AIs is relatively high exposure to childhood adversity in reservation communities. Reports indicate that experiences of adversity are more prevalent in reservation samples than among others in the United States, particularly among women (Manson et al., 2005). Research in other populations clearly indicates a link between exposure to adversity, particularly during childhood, and substance use disorders (Felitti et al., 1998; Kessler et al., 1997; Turner and Lloyd, 1995; Turner and Lloyd, 2003). Thus, a relationship between adversity and risk for dependence among AIs comparable to that observed in other populations might help to explain relatively high rates of substance dependence among AIs. In addition, variation in exposure to adversity across reservation communities might explain reports of inter-tribal variation in dependence, as well as variation related to gender within and across tribes (Beals et al., 2003b; Hawkins et al., 2004). Research to date has not specifically explored links between adversity and substance dependence among AIs; our goal in this study was to begin to fill this gap.

Three key findings emerging from studies of the relationship between exposure to adversity and substance dependence in other populations have shaped our research with AIs. First, evidence suggests that it is important to disentangle the proximal and distal effects of adversity on risk for the onset of substance problems (Lloyd and Taylor, 2006; Turner and Lloyd, 1995; Turner and Lloyd, 2003). Proximal effects are characterized as the immediate consequences of specific adverse events – the extent to which events are associated with an increase in the risk of symptom onset within a short time after event occurrence. Distal effects, in contrast, represent the long-term effects of exposure to adverse events; long after the immediate crisis of a particular adverse event has passed, the experience may retain the power to impact risk. In addition, the effects of adversity have been shown to be cumulative, such that each additional event adds incrementally to the risk of the later development of problematic substance use. Both proximal and distal events, by definition, occur before the onset of dependence symptoms. Because adversities that first occur after the onset of symptoms may be correlates or even consequences of dependence, they are excluded from models estimating risk for dependence onset.

Second, research suggests that exposure to adversity may be most potent, in terms of risk for substance dependence, when it occurs early in life (Kessler et al., 1997; Libby et al., in press; Libby et al., 2004). Findings that substance use may begin especially early in tribal communities suggest that the effects of adversity during childhood and adolescence may be particularly relevant to risk among AIs (Novins and Barón, 2004; Whitesell et al., in press). Our previous analyses of AI-SUPERPFP data have indicated strong relationships between childhood experiences of adversity, early initiation of substance use, and subsequent risk of substance use disorders (Whitesell et al., under review); these relationships have been found to be considerably weaker for adult experiences of adversity (Libby et al., in press). In addition, the first symptoms of dependence often emerge before adulthood. The median age of onset for substance disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication was 20 years (Kessler et al., 2005); in the AI communities that are the focus of our work, it was 18 years. Thus, in the current study, we focused on the age period during which the effects of adversity appear to be strongest and during which the risk of initial substance problems is at its peak, namely before age 21.

Third, evidence suggests that, in assessing the impact of adversity on risk for substance dependence, it is important to consider the role of prior psychiatric and conduct problems. This evidence demonstrates that exposure to adversity, in addition to being related to substance problems, also increases risk for depressive and anxiety disorders (Lloyd and Turner, 2003; Turner and Lloyd, 1995, 2004). Thus, it is possible that the effects of consequent psychiatric disorder, rather than adversity per se, account for increased risk of substance problems in the wake of adversity (e.g., depression experienced in response to adversity may engender substance use as a form of self-medication). Alternatively, the linkage between prior adversity and drug dependence may be artifactual. Early psychological problems, especially conduct problems, may expose children to greater adversity (e.g., children and adolescents with conduct disorders tend to engage in risky behaviors that may disproportionately expose them to adversity) and at the same time increase risk for drug dependence (Turner and Lloyd 1993).

Based on these findings, we explored relationships between childhood exposure to a variety of adverse events and the subsequent development of substance dependence symptoms during adolescence and early adulthood in two AI reservation samples. We examined both the proximal and distal effects of adversities on the age-related risk for onset of dependence symptoms controlling for tribe, gender, and the prior occurrence of mood and conduct disorders.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population and sample

We utilized data from the AI-SUPERPFP, a population-based study of two large, culturally distinct AI reservation communities. The populations of inference were 15- to 54-year-old enrolled members of two closely related Northern Plains (NP) tribes and a Southwest (SW) tribe who were living on or within 20 miles of their respective reservations at the time of sampling (1997). (To protect the confidentiality of the participating communities (Norton and Manson, 1996), we refer to these tribes by general descriptors rather than by specific tribal names.)

Stratified random sampling procedures were used, with strata defined by tribe, gender, and age (15–24 years, 25–34, 35–44, and 45+). Tribal rolls, the official enumeration of tribal members, were used to define the target population; records were selected randomly from these rolls for inclusion in replicates, which were then released as needed to reach the goal of about 1,500 interviews per tribe. In the SW and NP respectively, 46.6% and 39.2% of those listed in the tribal rolls were found to be living on or near the reservations; of those located and found eligible, 77% in the NP (N=1,638) and 74% in the SW (N=1,446) agreed to participate. The participation rate was slightly higher in the youngest cohort (84%) than in other cohorts (73%, 69%, and 72% for the older three age cohorts, respectively). The distribution of participants across age cohorts was comparable across samples. Sample weights accounted for differential selection probabilities across strata and for differential non-response by strata. A little more than half of the sample were female (N=1,677); 54% were living at or below the poverty line; 45% had a high school education (or equivalent); 28% had attended at least some college; 58% percent were currently employed; 56% were married. AI-SUPERPFP methods are described in greater detail elsewhere (Beals et al., 2003a); both the interview instrument and training manual are available for review on our website (http://www.uchsc.edu/ai/ncaianmhr/research/superpfp.htm).

2.2. Procedure

Before AI-SUPERPFP began, approvals for the research were obtained from all participating tribes. Written informed consent was obtained from all adult respondents, following complete description of the study; for minors, parental/guardian consent was obtained before requesting adolescent assent. Participants were interviewed individually by tribal members who had been given intensive training in research and interviewing methods; interviews were computer-assisted, with responses entered directly into laptop computers. Extensive quality control procedures verified that location, recruitment, and interview procedures were conducted in a standardized, reliable manner.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Onset of substance dependence symptoms

We were interested in how experiences of adversity might be linked to serious and persistent substance use problems; thus, we selected as our outcome measure symptoms of DSM-IV-defined substance dependence (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Symptom onset was defined as the youngest age at which any dependence symptom was reported, for any substance. Because the onset of substance dependence has been repeatedly demonstrated to peak during middle to late adolescence, we focused on a window of development around this period, exploring symptom onset between early adolescence (11 years of age) and early adulthood (21 years of age).

Symptoms are likely to represent significant disruption in people’s lives, whether or not the full criteria of dependence are met; thus, we included all reports of symptoms, rather than only symptoms among respondents meeting the full criteria for dependence. While a DSM-IV diagnosis of substance dependence offers a clear indication of the severe end of the continuum of substance problems, interventions may be most effective among individuals with subsyndromal levels of dependence symptoms, where early intervention efforts can have important implications for averting the progression to disorder. It should also be noted that the pattern of results presented here was largely paralleled by analyses in which symptoms were considered only among those eventually meeting criteria for disorder.

We focused on symptoms of dependence alone, rather than including symptoms of abuse, because dependence symptoms are more clearly indicative of significant substance problems, particularly among adolescents. We measured symptoms of dependence using items from the University of Michigan version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (UM-CIDI; World Health Organization, 1990), which had been adapted for AI communities as a part of a previous study (Beals et al., 2002). Most adaptations to the UM-CIDI consisted of minor changes in wording to make the language more consonant with community usage. The only substantive change to the dependence assessment was that, in recognition of the importance of the ceremonial use of the hallucinogen peyote in AI religious traditions, in particular in Native American Church ceremonies (Stewart, 1987), we discriminated between ceremonial and non-ceremonial use of this drug.

Symptoms of dependence were assessed separately for each of following 10 substances: alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, inhalants, tranquilizers, sedatives, analgesics, stimulants, hallucinogens (excluding ceremonial peyote), and heroin. Respondents who reported symptoms related to use of any of these substances were asked to report how old they were when each symptom began.

2.3.2. Adversity

Participants were asked to indicate whether or not they had experienced any of 30 specific adverse events, representing five types of adversity. Major Childhood Events were 12 events associated with potentially significant (but nonviolent) disruption in children’s lives, such as their own serious illness or hospitalization, separation from parents, parental unemployment, and parental divorce. Traumas were nine events that involved violence, such as rape or sexual assault, physical abuse or attack, or being in a natural disaster or serious accident. Three events were characterized as Witnessed Violence, experiences in which the respondent was an observer but not the direct victim of violence; most common in this category was witnessing family violence. When respondents reported learning that a loved one had been in a life-threatening situation, been assaulted, or committed suicide, these events were classified as Traumatic News. Finally, the deaths of a parent (or parental figure) or sibling were categorized as Significant Untimely Deaths; more normative experiences with death, such as the deaths of aging grandparents, were excluded, as were deaths outside the respondent’s immediate family. Events in each category were summed to create counts of each type of adversity; all events were summed to create an overall count of adversities.

2.3.2.1. Prior adversity

We recognized the need to isolate the potential effects of adversity on dependence symptoms – the focus of our research questions – from effects such symptoms might have on exposure to adversity. Thus, our measures included questions regarding not only the timing of dependence symptoms, as described above, but also the timing of adverse events. For each event reported, respondents were asked to indicate the age at which it first occurred and, if it happened more than once, the age at which it was last experienced. These data allowed us to determine the temporal relationship between experiences of adversity and onset of substance symptoms, and we defined prior adversities as those that predated the first reported symptom of dependence. Only prior adversities were included in analyses.

2.3.2.2. Proximal and distal adversity

We further classified prior adversities as either proximal or distal to the onset of dependence symptoms. Separate measures of proximal adversities were constructed for each age during the period of interest in this study (11 to 21 years); for each of these target ages, if any prior adversities were reported to have occurred within one year before that target age (i.e., age at adversity = target age − 1), proximal adversity was coded as 1; if no prior adversities were reported during that one-year window, proximal adversity was coded as 0. Few respondents reported more than one proximal adversity at any target age, so reports of one or more adversity were combined into a single indicator category. Each respondent, thus, had 11 measures of proximal adversity, indicating the presence or absence of reports of proximal adversities when they were 11 years old, 12 years old, and so on through when they were 21 years old.

Distal adversities were defined as any prior adversities reported to have first occurred more than one year before the target age (i.e., age at adversity ≤ target age − 2). Measures of distal adversities corresponding to each age from 11 to 21 years were constructed in a similar manner to measures of proximal adversity, though in this case we counted the number of prior adversities rather than simply indicating the presence or absence of any adversity. Our measures of distal adversity, thus, were cumulative measures, each reflecting the accumulation of adverse experiences and allowing examination of the collective effects of multiple adversities on risk for subsequent substance problems. Because the distribution of distal adversity counts was highly skewed, with few respondents reporting five or more adversities (especially by early adolescence), we coded five or more adversities as a single category. We conducted parallel analyses truncating the count of adversities at 10, rather than five, to capture greater variability in the counts of adversities among older participants and found virtually identical estimates of the relationship between cumulative adversity and risk of dependence onset.

2.4. Previous psychiatric symptoms

2.4.1. Mood problems

To determine whether mood disorder might have accounted for the link between exposure to adversity and dependence symptoms, we first identified the age when symptoms of mood problems first occurred. DSM-IV mood disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), like substance disorders, were assessed with items from the University of Michigan version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (UM-CIDI (World Health Organization, 1990)). Five types of mood disorder were included in the assessment used here: Major Depressive Episode, Dysthymia, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. Respondents who indicated symptoms of any of these disorders were asked a follow-up question regarding the age when symptoms were first experienced. The age of onset of mood symptoms was defined as the youngest age at which any symptom of any of these 5 disorders was reported.

2.4.1.2. Prior mood symptoms

As with adversities, we were concerned that mood symptoms could represent either precursors or sequelae of dependence symptoms; thus we excluded symptoms with onset after the first reported symptoms of substance use. In addition, in order to examine the effects of mood symptoms at each age in the hazard curves, we created 11 indicators of mood problems (one for each age from 11 to 21) reflecting whether or not symptoms had occurred before that age (one year or more before target age) and prior to any dependence symptoms. These indicators were included as time-varying covariates in subsequent analyses.

2.4.2. Conduct problems

Because conduct disorders have been found to be strongly related to substance disorders (Cloninger et al., 1995), we also included measures of conduct problems. As with the other psychiatric disorder modules, the UM-CIDI was the original source of the adapted AI-SUPERPFP conduct disorder module. Conduct problems assessed 13 behaviors, including running away from home, stealing, and starting fights. Although age at onset of the conduct disorder symptoms was not asked, participants were specifically instructed to report only conduct problems experienced before age 15. Since the risk of onset of dependence symptoms was very low before age 15 (mean age of onset in the AI-SUPERPFP sample was 19.1 years, median 18.0 years), this restricted conduct symptoms primarily to those occurring prior to the onset of dependence symptoms. Because we did not have specific age-related information on conduct symptoms, the presence or absence of conduct problems was included as a time-invariant covariate in subsequent analyses.

2.6. Analyses

Variable construction was completed with SPSS (SPSS, 2001) and SAS (SAS Institute Inc., 2002–2003); discrete-time survival analyses (DTSA) (Singer and Willett, 1993, 2003; Willett and Singer, 1993) were conducted using Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2006). DTSA analyses began with fitting a baseline hazard model for onset of dependence symptoms, across 1-year periods from age 11 to age 21. Only a very small percentage (2%) of the respondents who reported dependence symptoms said those symptoms began before age 11; these respondents were left-censored (i.e., they already had symptoms before the focal period, 11–21 years of age, began). Twenty-five percent of respondents who reported dependence symptoms said that those symptoms did not begin until they were adults, after age 21; because we were focusing here on the onset of symptoms during childhood and adolescence, these respondents were right-censored (i.e., they did not report symptoms before the end of the time period of interest). Hazard estimates represent the probability that individuals with no symptoms of dependence before each particular age would experience symptoms at that age.

Next we tested a series of hierarchical models in which we systematically added covariates to estimate how each, in turn, was related to the hazard. Significant covariate coefficients indicated increased or decreased likelihood of onset of dependence symptoms in the presence of the covariate. First we included tribe and gender, and the interaction between the two, as time-invariant covariates to determine whether, as we expected, the age-related risk of dependence onset varied across these groups. Next we added proximal adversity, a time-varying covariate, to determine whether experiences of adversity were associated with immediate (in the same year) elevations in risk of symptom onset. We next added the cumulative count of distal adversities (time-varying covariate), to explore whether the accumulation of past adverse experiences significantly impacted hazard at each age. We then tested the interaction of proximal and distal adversities and, thus, whether the impact of each was related to the other. Finally, we tested a model that included both previous symptoms of mood disorder (time-varying covariate) and childhood conduct disorder (time-invariant covariate), to determine the extent to which these factors accounted for the effects of adversity on dependence symptoms.

To determine whether the addition of each covariate improved the fit of the model, we compared the Bayesian Information Criteria, sample-size adjusted (BICSSA), across models. The BICSSA is a measure of model fit that adjusts for both the number of model parameters and the size of the sample; lower BICSSA values represent better overall fit. Thus, when the addition of a covariate to a model reduced the BICSSA, we retained the covariate in subsequent models. For each covariate added to the model, we began with an assumption of proportional odds (i.e., that the effect of the covariate would be constant across ages 11 to 21); however, we also tested a non-proportional odds model, to determine whether the effect varied depending on developmental period. For all models, the non-proportional model represented a poorer fit than did the proportional model (as indicated by a higher BICSSA value); thus proportional odds models were retained.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of substance dependence and adversity

Table 1 shows the prevalence of both substance dependence and childhood adversity, by tribe and gender; these estimates used sample weights that accounted for differential selection probabilities and non-response by age and gender strata. There were significant differences in the rates of dependence across these samples: NP males had the highest rate of dependence, significantly more than either group of females; both SW males and NP females also had rates significantly higher than that of SW females. The mean age of symptom onset, however, did not differ across either tribe or gender groups, hovering around 19 – 20 years of age in all groups.

Table 1.

Prevalence, mean levels, and age of onset of substance dependence, adversity, mood disorder, and conduct problems, by tribe and gender (with 95% confidence intervals), accounting for sampling weights.

| Southwest

|

Northern Plains

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |

| Prevalence (%) of DSM-IV substance dependence | 19.7 (16.6–23.2) | 6.0 (4.5–7.9) | 21.6 (18.7–24.9) | 15.1 (12.6–17.9) |

| Prevalence (%) of adversity | 85.2 (82.0–87.9) | 87.6 (85.1–89.7) | 83.1 (80.0–85.8) | 88.4 (85.9–90.5) |

| Prevalence (%) of DSM-IV mood disorder | 19.4 (16.4–22.9) | 28.1 (25.0–31.4) | 14.7 (12.2–17.5) | 25.7 (22.7–29.0) |

| Age of first substance dependence symptom | 19.3 (18.6–20.0) | 19.6 (18.7–20.4) | 18.8 (18.2–19.5) | 20.1 (19.3–20.8) |

| Age of first adverse experience | 11.0 (10.2–11.8) | 10.1 (9.4–10.7) | 10.2 (9.5–10.8) | 9.4 (8.8–9.9) |

| Age of first mood symptom | 22.1 (20.5–23.8) | 25.2 (24.0–26.4) | 25.3 (23.2–27.4) | 26.0 (24.4–27.6) |

| Mean conduct disorder problems (before age 15) | .31 (.28–.34) | .15 (.14–.17) | .32 (.30–.35) | .23 (.20–.25) |

| Mean number of reported adversities | 3.53 (3.3–3.8) | 3.86 (3.6–4.1) | 4.28 (4.0–4.6) | 4.60 (4.3–4.9) |

Adversity was generally more prevalent and reported to have occurred earlier among females than among males, and in the NP as compared with the SW. NP females reported the highest prevalence of adversity, with 88% reporting lifetime exposure to at least one of the 30 adverse experiences we asked about. NP females also reported the greatest mean count of adverse experiences, significantly more than either SW males or SW females. In addition, NP females reported the youngest age at first exposure to adversity, though the age was significantly different only from that reported by SW males.

3.2. Rates of proximal and distal adversity across ages 11 to 21

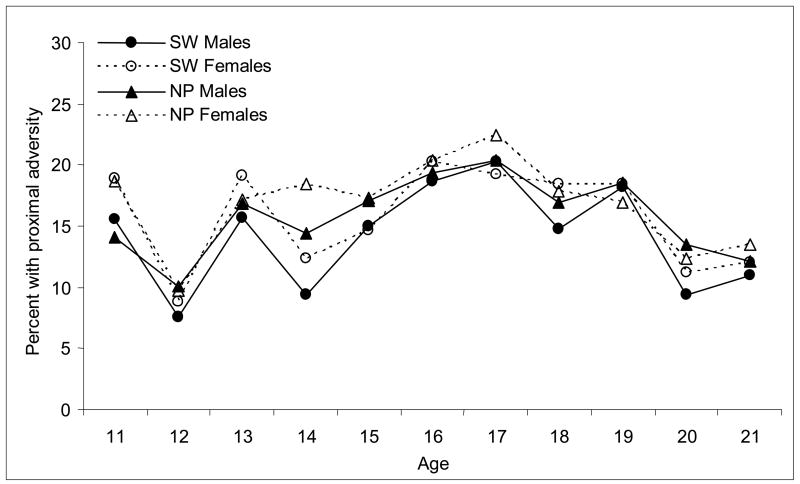

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of prior adversity reported as having occurred proximal to each age from 11 to 21 years. As is evident in the figure, adversity was more common during middle to late adolescence, with exposure peaking around 16 to 17 years of age in each tribe and gender group. Across all ages, the only significant differences among tribe and gender groups were found at age 14, when NP females were more likely than either SW males or SW females to report proximal adversity; the difference between NP males and SW males at age 14 approached significance (p=.051).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of proximal adversity by age, tribe, and gender.

Figure 2 displays the mean number of distal adversities reported to have occurred prior to each age. The measure of distal adversity was cumulative, i.e., the count of all adversities reported to have occurred more than one year before each age period; thus, the average number of distal adversities necessarily increased over adolescence (or at least could not have decreased), as reflected in the figure. Of more interest, however, were significant differences in cumulative distal adversity related to tribe and gender; NP females had consistently higher levels of cumulative distal adversity than did SW males.

Figure 2.

Mean count of cumulative distal adversities by age, tribe, and gender.

3.3. Age-related hazard of onset of substance dependence symptoms from ages 11 to 21

3.3.1. Tribe, gender, and risk of symptom onset

Figure 3 shows the results of the DTSA of onset of dependence symptoms, taking into account the effects of tribe, gender, and the interaction of tribe and gender on risk of symptom onset. These models did not include sample weights, since Mplus is not yet equipped to handle complex sampling designs; given that we are focusing here on relationships among variables rather than on obtaining accurate estimates of prevalence, the inclusion of weights is not likely to be critical. The risk of symptom onset was very low at age 11, grew steadily through early adolescence, peaked between 16 and 18 years of age, then declined and leveled off. Although we did not model the hazard beyond age 21 here, other analyses show that the risk of onset declines somewhat further in early adulthood and remains low through the end of our sampling period (age 54).

Figure 3.

Age-specific hazard of onset of substance dependence symptoms from 11 to 21 years, by tribe and gender.

Evident in hazard curves shown in Figure 3 are gender and tribe differences in risk of dependence symptoms. Across adolescence, males in both tribal groups had consistently higher risk of symptom onset than did females. Tribal differences, while not as strong as gender differences, were nevertheless significant and consistent: Respondents in the NP had greater risk of symptom onset than did those in the SW. A significant tribe-by-gender interaction indicated that tribal differences were somewhat greater among females than among males and that gender differences were greater in the SW than in the NP.

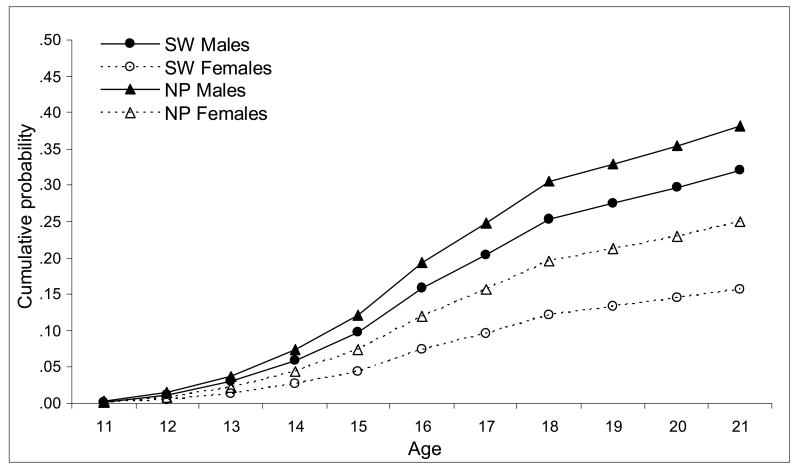

Figure 4 presents another perspective on patterns of dependence symptom onset across adolescence, the cumulative probability of symptoms and, thus, the cumulative effect of tribal and gender differences in age-related risk of onset. As this figure shows, dependence symptoms were fairly common among NP males, with 38% reporting at least one symptom by age 21. At the other extreme, only 16% of SW females reported any symptoms by age 21. SW males and NP females fell between, with 32% and 25%, respectively, reporting symptoms by age 21. These differences in cumulative probability of symptom onset are reflective of differences in prevalence of SUD among these tribal and gender groups shown in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Estimated cumulative probability of substance dependence symptoms by age 21, by age, tribe, and gender.

3.3.2. Proximal adversity and risk of symptom onset

Table 2 presents the set of hierarchical models estimating the relationships of tribe, gender, and proximal and distal adversities to risk of onset of dependence symptoms. Model 1 provides the parameter estimates for tribe, gender, and their interaction as depicted in Figures 3 and 4. In Model 2, proximal adversity was added to tribe and gender, resulting in a better-fitting model, as indicated by the reduction in the BICSSA value. The coefficient for proximal adversity was statistically significant (OR=2.23, p<.001). Further, the proportional odds model fit the data better than did a non-proportional model. Tests of interactions between proximal adversity and both tribe and gender showed no significant effects. Thus, at each age and among respondents who had no previous dependence symptoms, those who reported proximal adversity were more than twice as likely to experience the onset of symptoms as were those who did not report proximal adversity.

Table 2.

Hierarchical models of hazard of substance dependence symptom onset across ages 11–22 (N=2,956), including demographic predictors (Model 1), adversities (Models 2 – 4) and prior mood and conduct problems (Model 5).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics1 | |||||

| Tribe (NP) | 1.68 (1.39–2.04) | 1.68 (1.39–2.03) | 1.65 (1.36–2.00) | 1.65 (1.36–2.00) | 1.64 (1.31–2.06) |

| Gender (male) | 2.29 (1.89–2.78) | 2.34 (1.93–2.84) | 2.51 (2.05–3.07) | 2.52 (2.06–3.07) | 2.59 (1.97–3.39) |

| Gender by Tribe (NP male) | .74 (.58–.95) | .73 (.56–.95) | .72 (.56–.92) | .72 (.56–.92) | .76 (.57–1.01) |

| Prior Adversities2 | |||||

| Proximal3 | 2.23 (1.95–2.55) | 1.79 (1.55–2.06) | 2.44 (1.91–3.11) | 2.46 (1.90–3.18) | |

| Cumulative Distal4 | 1.23 (1.18–1.29) | 1.27 (1.22–1.32) | 1.28 (1.19–1.39) | ||

| Proximal by Cumulative Distal | .90 (.83–.97) | .89 (.82–.96) | |||

| Prior Mood Disorder2 | 3.86 (2.05–7.24) | ||||

| Childhood Conduct Problems1 | 1.26 (1.08–1.47) | ||||

| Sample-size adjusted BIC | 7,007 | 6,933 | 6,843 | 6,842 | 6,802 |

Gender, tribe, and conduct problems were time-invariant covariates

Adversities and previous mood symptoms were time-varying covariates

Proximal adversity was coded 1 in each age period if 1 or more adversities occurred 1 year before the age period and prior to the onset of first substance dependence symptoms and coded 0 if no adversities were reported within this period.

Distal adversities at each age period were the total number of adversities first occurring more than 1 year prior to the age period and prior to the onset of first substance dependence symptoms; counts of more than 5 were truncated at 5.

Model 3 included distal adversities; in particular, we tested whether the count of prior adversities reported to have occurred more than one year before was associated with increased risk of symptom onset beyond that associated with proximal adversity. The addition of distal adversity improved the fit of the model (BICSSA=6,842, compared to BICSSA=6,933 for Model 2). Tests of alternative models with non-linear effects (e.g., quadratic) revealed the best fit was for a linear model in which each additional adversity added monotonically to the risk of symptom onset. As with proximal adversity, the proportional odds model fit the data better than the non-proportional odds model, indicating that the effects of distal adversity were consistent across adolescence, and interactions between distal adversity and both tribe and gender were found to be nonsignificant. The OR of 1.23 (see Table 2) indicates that with each additional distal adversity, the risk of substance symptom onset increased by 20%, independent of the effects of proximal adversity (the OR for proximal adversity was relatively smaller when distal adversity was included, but the confidence interval for the ORs with and without distal adversity overlapped one another). With this additive model, then, cumulative experiences of adversities, coupled with current experiences of adversity, posed the greatest risk for dependence symptom onset.

Next, we explored whether the association of cumulative distal adversity with risk of symptom onset might be different in the presence and absence of proximal adversity; thus, Model 4 included the interaction between proximal and distal adversity. The interaction effect was small, but, as we expected, it indicated that the effect of distal adversity was less evident in the presence of proximal events; the adjusted OR for the effect of distal adversity in the presence of proximal adversity (i.e., proximal adversity = 1) was 1.3 (a 30% increase in risk) compared to 1.1 (a 10% increase in risk) in the absence of such adversity (proximal adversity = 0). Alternatively, we can look at how the effects of proximal adversity varied across counts of distal adversity. When no distal adversities were reported, the adjusted OR for proximal adversity was 2.5 (p<.001); with one distal adversity, the OR dropped to 2.2; with 2, it dropped to 2.0, and so on. This interaction effect must be interpreted cautiously however; it was small in magnitude and its inclusion in the model resulted in only a trivial reduction in the BICSSA value.

Although not shown here, we examined whether the occurrence of particular types of proximal adversity were differentially associated with risk of symptom onset, including separate indicators of each of the five different types of adversity included in our survey. This model did not represent an improvement in fit over the models with overall proximal adversity (BICSSA=6,849) but did suggest that some types of adversity were more strongly related to risk than were others. Traumas were most strongly related (OR=2.2, p<.001), followed by Traumatic News (OR=1.8, p<.01) and Witnessed Violence (OR=1.5, p<.01). Somewhat surprisingly, while the bivariate relationships between Major Childhood Events and Significant Untimely Deaths and symptom onset were significant (ORs of 1.5 and 1.6, respectively), neither remained significant when distal adversities and other types of proximal adversity were included in the model (ORs of 1.2 and 1.3, respectively). Interactions between distal adversities and each of these five types of adversity were tested and found to be nonsignificant, and non-proportional odds models were found to be poorer fits than were proportional odds models.

Across all models exploring the effects of proximal and distal adversity (Models 2–4), only minor variations in the estimates of the effects of tribe and gender were observed. Thus, although we observed substantial variation in the prevalence of exposure to adversity across tribe and gender groups – most notably, higher exposure among NP women – the relative effects of such exposure were consistent across these groups. Tribal and gender differences in the rates of substance dependence could not be explained by differential exposure to adversity.

3.3.3. Previous psychiatric disorder and childhood conduct problems

Our final model included a time-varying indicator of the presence or absence of symptoms of psychiatric disorder at each age, along with a time-invariant measure of the degree of childhood conduct problems. The results of this model are shown in Table 2, Model 5; the fit of this model was better, by the BICSSA criterion, than Model 4. As can be seen, the effects of both previous psychiatric symptoms and conduct problems were significant; however, the inclusion of these factors had only trivial effects on the magnitudes of other covariates in the model. Thus, the effects of adversity in relation to risk of dependence symptom onset were not accounted for by the prior occurrence of either psychiatric or conduct problems.

4. Discussion

4.1. Culture, gender, and the development of substance dependence

As anticipated, the risk of dependence symptom onset was strongly related to both tribe and gender. The significant interaction between tribe and gender showed that although males were at greater risk for symptom onset than were females in both tribes, their risk relative to females in their own tribe was significantly greater in the SW than in the NP. Likewise, the difference in risk between respondents in the NP and the SW was magnified among women. At each age from 11 to 21, NP males were at highest risk to begin experiencing dependence symptoms and SW females had the lowest risk; by age 21, the probability of symptoms among NP males was more than twice that among SW females. Thus, symptom onset was related to gender in different ways across the two tribes and the gender gap was relatively smaller in the NP than in the SW; relatively high risk among NP women resulted in a gap between men and women that was substantially smaller than what has typically been observed in other populations.

These findings are important for many reasons, but two seem particularly salient. First, the significant variation we found between these two AI tribes underscores the importance of not mixing individuals from disparate tribal cultures and communities into a single pan-Indian category. To do so would be to gloss over important differences in patterns of substance problems and to risk overlooking important clues to differential experiences across tribes that may be related to the development of substance problems.

Second, our findings underscore the importance of considering variation within cultures. Interactions between gender and tribe suggest that the context of development within tribes may differ in important ways for males and females and that the ways in which gender shapes development may vary across tribal cultures and contexts. To focus on tribal differences without attending to gender roles within tribe could not possibly provide a full picture of the social and cultural influences on substance problems. These findings are consistent with interpretations that emphasize the degree of disruption in traditional lifeways experienced by tribes of the NP, especially in comparison to the ways in which tribes of the SW have been better able to maintain traditional lifeways, including gender roles (May, 1982). Thus, in the SW, the preservation of culturally salient roles for women in a society that remains matrilineal may be protective against risk for substance problems; in the NP, the disruption of traditional ways in a society that was patrilineal may be especially problematic for women for reasons we do not yet understand.

Despite our expectation that differential exposure to adversity across tribe and gender groups might help to explain their differential risk for dependence symptoms, we did not find evidence of this. The effects of both tribe and gender were consistent, whether the effects of proximal and distal adversity were considered or whether they were excluded from the model. The effects of adversity, similarly, were consistent across tribe and gender groups (no interaction effects were significant). Thus, while exposure to adversity was clearly related to risk for substance dependence within as well as across gender and tribal groups, variations in such exposure contributed little toward explaining tribal and gender differences in such risk. While adversities appear, on the basis of these analyses, to constitute a key point of intervention, the fact that tribal differences remain, even after controlling for adversities, suggests that it will also be important to explore additional factors that may help explain these differences. For example, perhaps resources such as social support, education, or income are more common – or more protective – for women in the SW. On the other hand, women in the NP may face additional stressors, such as chronic strains, that intensify their risk of substance dependence. Also relevant here may be the different kinds of social and cultural expectations for women in the SW and NP, with the former being much less accepting of women’s drinking in either peer or family contexts. Finally, it will be important to explore alternative outcomes that might be more strongly related to adversity among women, such as depression or post-traumatic stress disorder.

4.2. Adversity and the development of substance dependence

Although they did not account for tribe and gender differences, experiences of adversity were themselves significantly related to the onset of dependence symptoms. Reports of one or more proximal adversities – events occurring within the past year – were strongly associated with the age-related risk of symptom onset, more than doubling the risk. No significant interactions emerged between proximal adversity and either tribe or gender; thus, across tribe and gender groups, experiences of adversity were uniformly associated with increased risk of developing dependence symptoms in the immediate aftermath of exposure to the adversity.

Cumulative distal adversities were also strongly related to developing dependence symptoms. As indicated in Model 3 (Table 2), the number of adversities reported to have occurred prior to a particular age was related to the risk of symptom onset at that age over and above the effect of proximal adversity. It appears, therefore, that cumulative experiences of adversity predisposed respondents to greater risk of dependence symptoms and that the magnitude of risk increased fairly systematically with the number of adversities experienced.

The small but significant interaction we found between proximal and cumulative distal adversities indicated that when respondents had encountered adversities within the past year, the cumulative effects of adversities experienced earlier in their lives were somewhat less apparent. In the absence of proximal adversities, the increase in risk associated with each distal adversity was about 20%, but when proximal adversities were included only about a 10% increase in risk was associated with distal adversity. Thus, when proximal events occurred, past events became less relevant to immediate risk. This interaction can also be interpreted in terms of the impact of proximal adversities, given a history of exposure to adverse events. With each additional distal adversity, the risk associated with proximal adversity decreased, going from an OR of 2.4 in the absence of distal adversity to an OR of 1.6 when 5 or more distal adversities were reported.

This interaction, coupled with our finding of a linear relationship between distal adversities and risk, suggests that while adversities had a cumulative effect on the risk of substance problems, they did not appear to have a “priming” effect; adversities added up to increase risk, but previous adversities did not appear to set the stage for more intense reactions to later adversities. The experience of an adversity had a strong relationship with risk of onset of dependence symptoms, even among respondents who had no previous history of adversity. In fact, the negative interaction between distal and proximal adversities shows that the effect of proximal adversity was strongest in this group. Previous adversities appeared to have the effect of blunting, to some extent, the impact of newly encountered adversities, at least on the risk of substance problems.

4.3. Limitations

The findings presented here contribute substantially to our understanding of the relationship between childhood adversity and subsequent dependence, particularly in regard to the timing of exposure to adversity and symptom onset. Nevertheless, these findings must be considered in light of their limitations. Limitations in the AI-SUPERPFP sample, study design, and instrumentation have been discussed at length elsewhere (Beals et al., 2003a). Most importantly, while the samples were well defined and justified, they were limited in cultural representation, age range, and residence. While these data emanated from careful sampling of two large AI tribes, they do not include a broad representation of the many tribal groups in the United States.

In addition, the cross-sectional design and reliance on retrospective self-reports were susceptible to errors associated with the filters of both time and response bias (Dohrenwend, 2006). Because of the nature of events we surveyed, however – significant life events and traumas not likely to be forgotten despite the passage of many years – we expect that respondents’ reports of the occurrence and approximate timing of events were reasonably reliable (Turner and Lloyd, 2003). In fact, these sorts of events often serve to define time, serving as major markers in individuals’ lives. In addition, our coding of the relative timing of events and substance symptoms was conservative, with prior proximal adversities occuring 1 year before symptom onset and prior distal adversities 2 or more years before symptoms. We also had no reason to anticipate differential recall bias in reports of adversities as compared to reports of substance symptoms. To test for the possibility of such bias, however, we compared separate models across age cohorts and found no meaningful differences in the effects of adversities on substance symptoms.

In our analyses, we were careful to consider only adversities reported to have first occurred prior to the onset of dependence symptoms, excluding those that could be ordered in time as beginning after symptom onset and thus potentially reflecting effects of substance problems rather than antecedents of them. However, our onset variables were all based on retrospective accounts of events and symptoms and undoubtedly were somewhat imprecise, especially for older respondents who were recalling events that had occurred many years before the time of the AI-SUPERPFP interview.

It is also important to note that our measures of adverse experiences allowed only for counts of types of events and not for counts of multiple or repeated occurrences of particular events within each category. Related to this is the problem of intra-category variability; the events classified by different respondents as exemplars of each type of event can vary greatly in terms of magnitude, source, and valence of events (Dohrenwend, 2006). This is a limitation common to most research utilizing life event inventories of the type employed here and is likely to result in conservative estimates of the effects of adverse events on subsequent problem development (Dohrenwend, 2006; Lloyd and Taylor, 2006; Turner and Lloyd, 2003).

4.4. Implications

These findings have important implications for efforts to prevent substance dependence among AIs. First, they clearly indicate that adverse experiences are associated with greater risk of substance problems during adolescence – specifically that prior experiences of adversity are associated with subsequent risk of substance problem onset, both in the short-term and over time, across tribe and gender groups. While this temporal link between prior adversity and later substance problems does not demonstrate that adversity causes substance problems, it does make it clear that, at the very least, these adversities presage substance problems. Thus, an important target for prevention of dependence among AI youth, as among youth in other populations (Turner and Lloyd, 2003), is the reduction in exposure to adversity and/or sequelae of adversity. Efforts to prevent dependence would do well to begin with a focus, not on substance use or misuse per se, but rather on attenuating the effects of adversity. Given the high rates of both adversity and substance use in these AI communities, this seems a particularly important agenda for intervention.

Several specific implications for intervention follow from these findings. First, efforts to prevent the development of substance problems must begin early in childhood, long before the peak periods of substance use initiation or symptom onset of adolescence. Childhood experiences are linked to increased risk both immediately and years later and, thus, mark the initial targets of intervention efforts. An obvious and primary goal in prevention with young AI children would be to reduce the extent to which they are exposed to stressful and traumatic events. Unfortunately, it is all too evident that such events are commonplace for many reservation children: thus a secondary pre-emptive goal would be to foster in young children the development of personal resources related to resilience – resources that will enable them to cope with perhaps inevitable adversity in a way that does not derail their development and lead them into risky maladaptive behaviors, such as excessive substance use. The significant proximal effect of adversities on symptom onset – the risk of symptom onset within the first year after the adverse event was more than double – suggests that children who are exposed to adversity should be directed toward intervention as quickly as possible. The strength of the effect of proximal adversity, even in the absence of distal adversity, makes it clear that a single adverse event can have powerful implications for risk of substance dependence and that even children with relatively serene histories should be included in efforts to build resilience and targeted for timely intervention when adversities arise. This point is further evident in the finding that the effects of adversity persist when controlling for previous mood and conduct problems; the relationship between adversity and risk for dependence symptoms could not be explained as the shared outcome of pre-existing psychiatric problems. Finally, children in chronically adverse environments should receive special attention in intervention efforts; their risk of dependence is particularly high and persistent, and they need support throughout adolescence as they continue to experience the cumulative effects of adverse events long after they have occurred, whether or not they encounter new adversities.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH48174, Manson and Beals, PIs; P01 MH42473, Manson, PI). Analyses for and writing of the article were also supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA14817, Beals, PI; R01 DA17803, Beals, PI).

AI-SUPERPFP would not have been possible without the significant contributions of many people. The following interviewers, computer/data management and administrative staff supplied energy and enthusiasm for an often difficult job: Anna E. Barón, Antonita Begay, Amelia I. Begay, Cathy A.E. Bell, Phyllis Brewer, Nelson Chee, Mary Cook, Helen J. Curley, Mary C. Davenport, Rhonda Wiegman Dick, Marvine D. Douville, Pearl Dull Knife, Geneva Emhoolah, Fay Flame, Roslyn Green, Billie K. Greene, Jack Herman, Tamara Holmes, Shelly Hubing, Cameron Joe, Louise F. Joe, Cheryl L. Martin, Jeff Miller, Robert H. Moran, Natalie K. Murphy, Melissa Nixon, Ralph L. Roanhorse, Margo Schwab, Jennifer Desserich, Donna M. Shangreaux, Matilda J. Shorty, Selena S. S. Simmons, Wileen Smith, Tina Standing Soldier, Jennifer Truel, Lori Trullinger, Arnold Tsinajinnie, Jennifer M. Warren, Intriga Wounded Head, Theresa (Dawn) Wright, Jenny J. Yazzie, and Sheila A. Young. We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of the Methods Advisory Group: Margarita Alegria, Evelyn I. Bromet, Dedra Buchwald, Peter Guarnaccia, Steve G. Heeringa, Ron Kessler, R. Jay Turner, and William A. Vega. Finally, we thank the tribal members who so generously answered all the questions asked of them.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV) 4. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Manson SM, Mitchell CM, Spicer P, AI-SUPERPFP Team. Cultural specificity and comparison in psychiatric epidemiology: Walking the tightrope in American Indian research. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2003a;27:259–289. doi: 10.1023/a:1025347130953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Manson SM, Whitesell NR, Spicer P, Novins DK, Mitchell CM The AI-SUPERPFP Team. Prevalence of DSM-IV disorders and attendant help-seeking in two American Indian reservation populations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005a;62:99–108. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Novins DK, Whitesell NR, Spicer P, Mitchell CM, Manson SM The AI-SUPERPFP Team. Prevalence of mental disorders and utilization of mental health services in two American Indian reservation populations: Mental health disparities in a national context. Am J Psychiatry. 2005b;162:1723–1732. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Spicer P, Mitchell CM, Novins DK, Manson SM The AI-SUPERPFP Team. Racial disparities in alcohol use: Comparison of two American Indian reservation populations with national data. Am J Public Health. 2003b;93:1683–1685. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauvais F. Trends in drug use among American Indian students and dropouts, 1975 to 1994. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:1594–1599. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.11.1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Sigvardssson S, Przybeck TR, Svrakic DM. Personality antecedents of alcoholism in a national probability sample. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;25:239–244. doi: 10.1007/BF02191803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP. Inventorying stressful life events as risk factors for psychopathology: Toward resolution of the problem of intracategory variability. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:477–495. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins EH, Cummins LH, Marlatt GA. Preventing substance abuse in American Indian and Alaska Native youth: Promising strategies for healthier communities. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:304–323. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Davis CG, Kendler KS. Childhood adversity and adult psychiatric disorder in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Psychol Med. 1997;27:1101–1119. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J, Beals J, Manson SM. A structural equation model of factors related to substance use among American Indian adolescents. Journal of Drug Issues 1992 [Google Scholar]

- Kunitz SJ, Gabriel KR, Levy JE, Henderson E, Lampert K, McCloskey J, Quintero G, Russell S, Vince A. Alcohol dependence and conduct disorder among Navajo Indians. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:159–167. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunitz SJ, Levy JE. Drinking careers: A twenty-five-year study of three Navajo populations. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Libby AM, Orton HD, Beals J The AI-SUPERPFP Team. Cumulative adversities and lifetime psychiatric and substance use disorders: Childhood and adult traumatic experiences in two American Indian tribes. Am J Public Health in press. [Google Scholar]

- Libby AM, Orton HD, Novins DK, Spicer P, Buchwald D, Beals J, Manson SM The AI-SUPERPFP Team. Childhood physical abuse and sexual abuse and subsequent alcohol and drug use disorders in two American Indian tribes. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:74–83. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd DA, Taylor J. Lifetime cumulative adversity, mental health and the risk of becoming a smoker, health: An Interdisciplinary. Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness, and Medicine. 2006;10:95–112. doi: 10.1177/1363459306058990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd DA, Turner RJ. Cumulative adversity and posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence from a diverse community sample of young adults. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2003;73:381–391. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.73.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM, Beals J, Klein SA, Croy CD. Social epidemiology of trauma among 2 American Indian reservation populations. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:851–859. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA. Substance abuse and American Indians: Prevalence and susceptibility. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1982;17:1185–1209. doi: 10.3109/10826088209056349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA. The epidemiology of alcohol abuse among American Indians: The mythical and real properties. American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 1995;18:121–143. [Google Scholar]

- May PA. Overview of alcohol abuse epidemiology for American Indian populations. In: Sandefur GD, Rindfuss RR, Cohen B, editors. Changing numbers, changing needs: American Indian demography and health. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C: 1996. pp. 235–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 1998–2006. [Google Scholar]

- Norton IM, Manson SM. Research in American Indian and Alaska Native communities: Navigating the cultural universe of values and process. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:856–860. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novins DK, Barón A. American Indian adolescent substance use: the hazards for substance use initiation and progression for adolescents aged 14 to 20. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:316–324. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200403000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell JM, Novins DK, Beals J, Spicer P. Disparities in patterns of alcohol use among reservation-based and geographically dispersed American Indian populations. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:107–116. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000153789.59228.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin RW, Long JC, Rasmussen JK, Albaugh B, Goldman D. Relationship of binge drinking to alcohol dependence, other psychiatric disorders, and behavioral problems in an American Indian tribe. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:518–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins L, Regier D. Psychiatric disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. MacMillan; New York, NY: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; Rockville, MD: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS Language. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 2002–2003. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. It’s about time: Using discrete-time survival analysis to study duration and the timing of events. Journal of Educational Statistics. 1993;18:155–195. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer P, Beals J, Mitchell CM, Novins DK, Croy CD, Manson SM The AI-SUPERPFP Team. The prevalence of DSM-III-R alcohol dependence in two American Indian reservation populations. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1785–1797. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000095864.45755.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS. SPSS. SPSS, Inc; Chicago: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart OC. Peyote religion. University of Oklahoma Press; Norman, OK: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. Lifetime traumas and mental health: The significance of cumulative adversity. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:360–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. Cumulative adversity and drug dependence in young adults: Racial/ethnic contrasts. Addiction. 2003;98:305–315. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. Stress burden and the lifetime incidence of psychiatric disorder in young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:481–488. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesell NR, Beals J, Mitchell CM, Manson SM, Turner RJ. Adversity in childhood and adolescence: Relationship to early substance use and substance use disorder among American Indians under review. [Google Scholar]

- Whitesell NR, Beals J, Mitchell CM, Novins DK, Spicer P, Manson SM The AI-SUPERPFP Team. Latent class analysis of substance use: Comparison of two American Indian reservation populations and a national sample. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:32–43. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesell NR, Beals J, Mitchell CM, Novins DK, Spicer P, O’Connell J, Manson SM. The AI-SUPERPFP Team, in press. Marijuana initiation in two American Indian reservation communities: Comparison to a national sample. Am J Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett JB, Singer JD. Investigating onset, cessation, relapse, and recovery: Why you should, and how you can, use discrete-time survival analysis to examine event occurrence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:952–965. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), Version 1.0. Work Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1990. [Google Scholar]