Abstract

Background and purpose:

Oxidative stress may be involved in the development of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs). Previous studies indicate that antioxidants protect against AAA formation during chronic angiotensin (Ang) II infusion in apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE0) mice. We here examine if these protective effects also occurred in aged ApoE0 mice.

Experimental approach:

Male ApoE0 mice (50–60 weeks) were randomly divided into 4 groups: saline, Ang II (1000 ng kg−1 min−1 for 4 weeks), Ang II plus antioxidants (0.1% vitamin E in food plus 0.1% vitamin C in drinking water), and Ang II plus losartan (30 mg kg−1 day−1).

Key results:

Exogenous Ang II increased systolic blood pressure by 40 mmHg and resulted in the formation of pseudoaneurysms (rupture and extramural haematoma) in the abdominal aorta in 50% of animals. True aneurysmal dilatation was rarely observed. Antioxidants decreased systemic oxidative stress (plasma malondialdehyde), but had only minor effects on aortic rupture, relative to the complete prevention by losartan. Immunohistochemistry revealed strong matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) expression in atherosclerotic plaques and at the sites of rupture. Antioxidants did not affect tumour necrosis factor-α-stimulated MMP-9 release from U937 cells. In addition, antioxidants had little effects on Ang II-induced renal dysfunction.

Conclusions and implications:

In contrast to previous findings in younger mice, antioxidants had only minor effects on Ang II-induced aortic rupture in aged mice. Our results demonstrate that the pathological features of the aneurysmal remodelling induced by Ang II in old ApoE0 mice are distinct from those of human AAA.

Keywords: abdominal aortic aneurysm, aged, angiotensin II, antioxidants, aortic rupture, apolipoprotein E-deficient, metalloproteinase

Introduction

Angiotensin II (Ang II) is an important regulatory peptide that is involved in maintaining cardiovascular homeostasis and also in the pathogenesis of various cardiovascular diseases. Several lines of evidence have indicated that many of the biological actions of Ang II are mediated, at least partly, by the generation of intracellular reactive oxygen species through the activation of a vascular reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (Hanna et al., 2002). For example, in endothelial cells, activation of the redox-sensitive transcription factor nuclear factor-κB and expression of the inflammatory adhesion molecule vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 induced by Ang II were blocked by antioxidants (Pueyo et al., 2000). In cardiac myocytes, blockade of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase activity or treatment with various antioxidants suppressed an Ang II-induced hypertrophic response (Nakamura et al., 1998; Nakagami et al., 2003). Moreover, Ang II-induced monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in renal proximal tubular cells was reduced by the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine by 80% (Tanifuji et al., 2005). These results suggest that targeting oxidant stress may have beneficial effects against Ang II-induced deleterious actions, such as inflammation, in cardiovascular tissues and kidneys.

Chronic infusion of Ang II in the hyperlipidemic apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE0) mice has been reported to produce lesions similar to human abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) (Daugherty et al., 2000). AAAs are characterized by localized, progressive thinning and dilation of the aortic wall, often associated with an inflammatory response in the vessel wall (Prisant and Mondy, 2004). Currently, an effective pharmacological treatment that can prevent the development, growth or rupture of AAA remains elusive, because the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying this disease are poorly understood. Moreover, the lack of an appropriate animal model hampers the investigation of mechanisms underpinning this condition. Several groups have provided evidence that increased vascular oxidative stress may influence the development of AAAs. For instance, Miller et al. (2002) have shown that in AAA patients, the reactive oxygen species production and lipid peroxidation were significantly increased in aneurysms as compared to normal aortic tissues. In a rat model of elastase perfusion-induced AAA, upregulation of antioxidant enzymes by increased blood flow or treatment with vitamin E prevented aneurysm formation (Nakahashi et al., 2002). Interestingly, it was reported that vitamin E treatment also reduced the incidence of AAA formation and aortic rupture in Ang II-infused ApoE0 mice (Gavrila et al., 2005). Moreover, AAA development induced by Ang II in mice was suppressed by deletion of the p47phox subunit of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (Thomas et al., 2006). All these results are consistent with the view that oxidative stress has an essential role in mediating Ang II-induced aortic aneurysmal remodelling. As AAAs occur mostly in older people (Singh et al., 2001), in this study, we aimed to examine whether the protective effects of antioxidants also occurred in aged ApoE0 mice.

In addition, Ang II also has a critical role in the pathogenesis of impaired renal function in various diseases, based on numerous reports that inhibition of the Ang II system, by either angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or by angiotensin II receptor type-1 receptor antagonists, has obvious renal protective actions (Remuzzi et al., 2005). There is increased oxidative stress in the kidney in conditions such as ischemia–reperfusion injury, chronic renal failure, hypertension and diabetic nephropathy (Vaziri, 2004; Araujo and Welch, 2006) and impaired renal functions may have a fundamental role in the development of cardiovascular disease (Varma et al., 2005). Some pilot animal studies have shown that antioxidant interventions may have beneficial effects on renal function under certain pathophysiological conditions (Stulak et al., 2001; Guron et al., 2006). Therefore in the present study, we also examined alterations in the kidney during Ang II infusion.

Methods

Animal treatments and tissue collection

All animal studies were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee. Male ApoE0 mice (purchased from Animal Resource Centre, Western Australia, Australia) were maintained on a normal diet and used at 50–60 weeks of age. Animals were randomly divided into saline groups: saline (S), Ang II (A), Ang II plus antioxidant vitamins (AV) and Ang II plus the angiotensin II receptor type-1 receptor antagonist losartan (AL). Ang II (1000 ng kg−1 min−1 for 4 weeks; Daugherty et al., 2000; Gavrila et al., 2005) was administered via osmotic mini pumps (Alzet, Cupertino, CA, USA) embedded under the skin. Normal saline was used as a placebo control. In some pumps, losartan (30 mg kg−1 day−1) was mixed with Ang II. Vitamin E (±-α-tocopherol; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was mixed with food at a concentration of 0.1% (equivalent to ∼150 mg kg−1 day−1). Vitamin C (Sigma) was dissolved in drinking water at a concentration of 0.1% (equivalent to ∼150 mg kg−1 day−1). We used combined vitamins E+C treatment, because vitamin C has been shown to be able to prevent oxidation and depletion of vitamin E in cell membranes (May et al., 1998). All vitamin treatments were started 1 week before Ang II infusion.

Animals were heparinized and killed by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital. Blood samples were taken from the right atria and then the animals were briefly perfused with cold saline from the left ventricle at 100 mm Hg to remove residual blood. The aorta was removed and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, while some of the samples were directly frozen in the Tissue-Tek (Torrance, CA, USA) optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound without fixation (for immunohistochemistry). Kidneys and plasma samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Urine samples were collected over a 24-h period 1 day before death.

Conscious blood pressure measurement

Systolic blood pressure was measured in conscious mice using a noninvasive tail-cuff blood pressure system (IITC Inc., Woodland Hills, CA, USA). Animals were acclimatized to the procedure by several mock sessions 1 week before the study. In each measurement, blood pressure (BP) readings were taken for at least three times and the averaged values were reported.

Morphological analysis

Morphological examination of the aorta was carried out as described previously (Jiang et al., 2003; Jones et al., 2005). After gross examination of the suprarenal region of the abdominal aorta for aneurysms, this region was cutout and sectioned at 10 μm thickness. Paraffin sections were stained with haematoxylin/eosin and, for the elastic laminas, with the Verhoeff's von Giessen staining. The aortic arches were processed longitudinally and used to assess the atherosclerotic lesions (Jiang et al., 2003).

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously (Jiang et al., 2006). Briefly, protein samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10% polyacrylamide) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.5) containing Tween 20 (0.1%) for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated with primary antibodies in the same solution overnight at 4 °C. After wash and hybridization with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, membranes were developed with an ECL kit (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

Acetone-fixed cryosections of abdominal aorta were incubated with 3% H2O2 to quench the endogenous peroxidase activity, blocked with 10% normal horse serum, and then incubated with rabbit anti-matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) polyclonal antibody (Chemicon, Billerica, MA, USA) diluted in 10% serum (1:100) at 4 °C for two overnights. Normal rabbit IgG (Sigma) was used as negative controls. Slides were then developed with an ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and AEC chromogen (Dako, DK-2600, Glostrup, Denmark). To quantify the intensity of MMP-9 immunoreactivity, at least five consecutive slides (100 μm apart) from each sample were scored by an independent assessor without knowledge of the treatments, using an arbitrary score system of 5 with an interval of 0.5. Only the non-ruptured part of the suprarenal abdominal aorta was included in this experiment.

Gelatin zymography

Standard gelatin zymography was performed to measure the activity of MMPs according to Bellosta et al. (1998) with slight modifications. Conditioned medium (10 μl), plasma (10 μl of 1:25 diluted samples) or tissue homogenates (10 μg protein) were separated in 10% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels containing gelatin (1 mg ml−1) under non-reducing conditions. After electrophoresis, gels were washed with 2.5% Triton X-100 at room temperature and then incubated in a developing buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 1 μM ZnCl2, and 0.05% Brij-35, pH 7.5) overnight at 37 °C. The specificity of gelatinase activity was confirmed by inhibition experiments in which 20 mM EDTA was added to the developing buffer. After incubation, the gels were stained with a solution of 0.1% Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) in 25% methanol and 7% acetic acid. Total gelatinolytic activities were identified by clear bands against the blue background after destaining with the methanol/acetic acid solution. The identity of each MMP was confirmed using purified mouse MMP-2 and MMP-9 (Sigma) as positive controls.

Thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances assay

The oxidative stress was assessed by measuring the lipid peroxidation product malondialdehyde (MDA), using the thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances assay as described by Satoh (1978). Thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances reagent was prepared by mixing 1:1 of 20% trichloroacetic acid with 1% thiobarbituric acid (Sigma). Aliquots of 20 μl plasma were diluted in 80 μl distilled H2O. The sample was mixed with 400 μl thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances reagent, heated to 95 °C for 20 min, and then cooled to room temperature. The coloured product was extracted with 500 μl n-butanol by vigorous shaking for 20 min, and the organic phase was separated from the mixture by centrifugation at 5000 g for 5 min. A volume of 300 μl of the supernatant was loaded into a 96-well plate, and the absorbance at 550 nm (A550) was determined with a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Serial dilutions of 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane (malonaldehyde bis(dimethyl acetal)) were used to construct the standard curve.

Urine protein and creatinine measurement

Protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent (Cat. no. 500-0006). Creatinine was assayed with a colorimetric reaction with alkaline picric acid as described (Slot, 1965). The final red product was measured by reading absorbance at 505 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices).

U937 cell culture

The human monocytic U937 cells were purchased from ATCC and maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum under 95% O2/5% CO2 at 37 °C. Terminal differentiation to macrophages was induced by combined incubation with all-trans retinoic acid and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (both of 100 nM; Sigma) for 72 h with an initial cell density of 2 × 105 ml−1 (Caron et al., 1994). Before treatment, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and resuspended in serum-free medium to 106 cells ml−1. Ang II (100 nM) or human tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α, 20 ng ml−1; Sigma), with or without antioxidants, were added and incubated for 24 h in the serum-free medium.

Data and statistics

Data were presented as mean±s.e.mean. The mean data were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance followed by Newman–Keuls t-test (for multiple comparisons) unless indicated otherwise. A P-value of <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Ang II increased blood pressure, which was not affected by antioxidants

In old ApoE0 mice, chronic infusion of Ang II for 4 weeks significantly increased the systolic blood pressure by 40 mm Hg (Table 1), while saline treatment did not have any effect on systolic blood pressure. There was no difference in baseline systolic blood pressure among all treatment groups. Treatment with antioxidants had a little effect on Ang II-induced increase in BP, which was totally blocked by the angiotensin II receptor type-1 receptor antagonist losartan (Table 1). Ang II treatment did not alter other physiological parameters including body weight, heart rate, plasma total cholesterol and triglycerides (Table 1). Losartan reduced the plasma triglycerides (P<0.005 vs A, unpaired t-test), which may be related to the activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ by losartan metabolites (Schupp et al., 2006).

Table 1.

Systolic blood pressure and other physiological parameters in ApoE0 mice during chronic Ang II infusion

| Saline | Ang II | Ang II+antioxidants | Ang II+losartan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline SBP (mm Hg) | 101±3 | 98±4 | 98±2 | 94±6 |

| SBP after Ang II | 102±7 | 140±8† | 126±6† | 106±13 |

| Heart rate (beats min−1) | 640±32 | 640±21 | 680±12 | 639±30 |

| Body weight (g) | 32.1±1.4 | 29.8±1.1 | 29.0±1.5 | 28.8±1.5 |

| Total cholesterol (mM) | 17.3±1.3 | 17.1±1.7 | 15.0±3.7 | 15.1±0.5 |

| Plasma triglycerides (mM) | 0.83±0.13 | 0.96±0.075 | 0.90±0.17 | 0.47±0.067* |

Abbreviations: Ang II, angiotensin II; ANOVA, analysis of variance; ApoE0, apolipoprotein E-deficient mice; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Data are mean±s.e. *P<0.005 vs Ang II, unpaired t-test; †P<0.05 vs baseline values, one-way ANOVA, n=5–10.

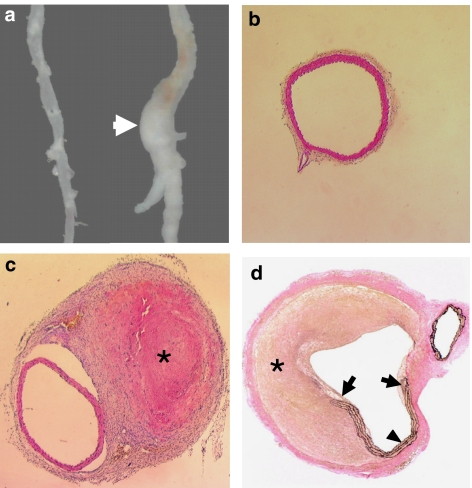

Ang II induced abdominal aortic rupture

Ang II infusion for 4 weeks resulted in aneurysm-like expansive lesions at the suprarenal region of the abdominal aorta in 50% of these old mice (Figure 1a). No similar lesions were found in the saline group. Histology examination of these lesions revealed that none of these expansions were true aneurysms, but were encapsulated extramural thrombi (pseudoaneurysms) (Figures 1b and c). In all cases, we could identify a rupture of the aortic wall that was associated with the thrombus (Figure 1d). At 4 weeks, many infiltrating leukocytes can be found in most of the thrombi, indicating a process of organization. The thrombi extended beyond the site of rupture alongside the aortic trunk and were totally encapsulated by thick fibrous tissue, forming a pseudolumen (Figures 1c and d). Examination of the geometry (lumen and external diameters) of the intact segment immediately adjacent to the rupture site did not reveal an aneurysmal dilatation of the aorta (Table 2). On the other hand, Ang II induced significant medial hypertrophy, as shown by the increased mean medial thickness (Table 2). The total intimal area of the aortic arch was not significantly changed by Ang II infusion, indicating that Ang II had minimal effects on the total volume of the advanced atherosclerotic lesions in these aged ApoE0 mice (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Histopathology of Ang II infusion-induced pseudoaneurysm in the abdominal aorta of aged ApoE0 mice. (a) Gross appearance of the pseudoaneurysm (arrow). The aorta from saline treated animal was shown on the left as control. (b) Haematoxylin andeosin (H&E) staining of the transverse section of the suprarenal abdominal aorta from the control group (× 40). (c) Transverse section (× 40) cut from the segment immediately adjacent to the rupture site showing the intact aortic wall. True aneurysmal expansion of the aorta could not be identified. *A thrombus encapsulated in fibrous tissues (H&E staining). (d) Verhoeff's von Giessen staining showing the total rupture of the aortic wall (arrows). A pseudolumen was formed by the thrombus (*) and the residual vessel wall (arrowhead) (× 40). Ang II, Angiotensin II; ApoE0, apolipoprotein E-deficient.

Table 2.

Effects of Ang II and antioxidant vitamins on aortic rupture and remodelling in ApoE0 mice

| Saline | Ang II | Ang II+antioxidants | Ang II+losartan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number | 10 | 14 | 13 | 9 |

| Aortic rupture (% incidence) | 0 (0%) | 7 (50%) | 4 (30.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Medial thickness (μm) | 36.8±2.5 | 59.8±5.9* | 75.3±3.7* | 45.4±5.9 |

| Lumen diameter (μm) | 350.3±25.5 | 271.4±46.0 | 376.8±38.5 | 376.3±79.6 |

| External diameter (μm) | 423.5±28.5 | 370.4±67.6 | 433.8±80.8 | 439.0±89.1 |

| Arch intimal area (× 105 μm2) | 4.8±1.6 | 4.3±1.1 | 6.9±1.6 | — |

Abbreviations: Ang II, angiotensin II; ANOVA, analysis of variance; ApoE0, apolipoprotein E-deficient mice.

Medial thickness, internal and external diameters of the abdominal aorta in animals with pseudoaneurysms were measured in the intact segment immediately adjacent to the rupture site. The external diameter was measured between the borders of the medial layer, because thickened adventitia was found in some of the Ang II-treated animals. The total intimal areas were measured in longitudinal sections of the aortic arch between the base of the aortic valve and the first intercostal branch. Data are mean±s.e. *P<0.05 vs saline, one-way ANOVA.

To examine whether Ang II-induced high BP is sufficient to induce aortic rupture, we treated aged wild-type mice with Ang II at the same dose. While Ang II induced similar BP change in these mice, no pseudoaneurysm formation was observed.

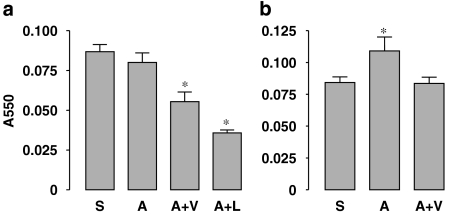

Antioxidants decreased oxidative stress but did not prevent aortic rupture

In the Ang II alone group, the incidence of aortic rupture (pseudoaneurysms) was 50%. Concomitant treatment with antioxidants (vitamin C+vitamin E) appeared to reduce the incidence of aortic rupture (Table 2), but this was not statistically significant (P=0.31, χ-test). In contrast, co-treatment with losartan completely blocked Ang II-induced aortic rupture (Table 2). Also, antioxidants had a little effect on Ang II-induced medial hypertrophy, which was prevented by losartan (Table 2). To confirm that the dose of antioxidants used in this study was enough to suppress oxidative stress, we measured the plasma MDA levels, as an index of lipid peroxidation. As shown in Figure 2a, although Ang II alone did not significantly alter the plasma MDA levels as compared to the saline group, this was significantly decreased by antioxidants. This may be because systemic oxidative stress already exists before Ang II treatment. Losartan had an effect on plasma MDA, similar to those of the antioxidants. To confirm further the antioxidant effects, we measured the MDA level in kidney homogenates. In contrast to the plasma, kidney MDA levels were significantly increased in the Ang II group, indicating an increased local oxidative stress. This increase in kidney MDA by Ang II was normalized by antioxidants (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Effects of Ang II and antioxidants on the malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in the plasma (a) and kidney homogenates (b) measured by the thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) assay. S, saline; A, Ang II; V, antioxidant vitamins; L, losartan. Data are mean±s.e.mean. *P<0.05 vs saline, n=5–9. Ang II, Angiotensin II.

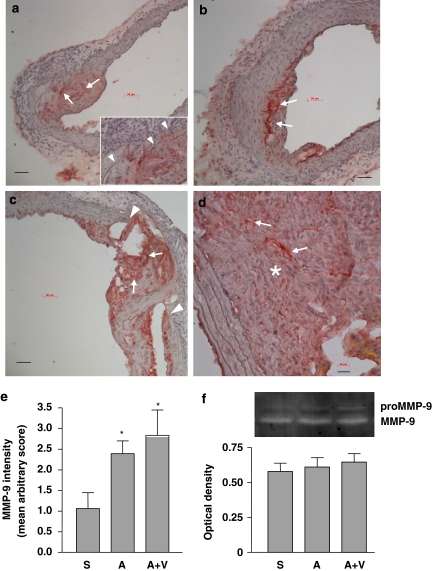

Matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in the abdominal aorta

Because increased MMP activity in the aorta has been implicated in the pathogenesis of Ang II-induced abdominal aneurysms in ApoE0 mice (Manning et al., 2003), we examined the association of MMP-9 expression and the abdominal aortic rupture.

Immunohistochemistry revealed that strong MMP-9 expression was always associated with the pre-existing atherosclerotic plaques in the abdominal aorta (Figure 3a). Infusion with Ang II did not change this pattern of expression (Figure 3b), but appeared to enhance MMP-9 production within the intima. Elastic lamina disruptions could be found in the aortic wall under most of the plaques examined (Figure 3a insert). In some specimens from the Ang II group, we identified total medial breakages in association with localized MMP-9 expression without haematoma formation, which may represent a precursor of the pseudoaneurysm (Figure 3c). MMP-9 was also highly expressed in organizing thrombi inside the sac of pseudoaneurysms (Figure 3d) and also at the sites of rupture (data not shown). The overall intensity of MMP-9 immunoreactivity in the non-ruptured part of the suprarenal abdominal aorta was higher in the Ang II group as compared to the saline group; and this increase in MMP-9 was not changed by antioxidants (Figure 3e). We also measured the MMP activity in plasma using gelatin zymography and did not find a significant difference of circulating MMP-9 activity among saline, Ang II and Ang II plus antioxidant vitamin groups (Figure 3f). These results suggest that local, atherosclerotic plaque-derived MMP-9 activity might have a role in the pathogenesis of Ang II-induced abdominal aortic rupture.

Figure 3.

Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) production in the aorta examined by immunohistochemistry (a–d) and in the plasma examined by gelatin zymography (f). Strong MMP-9 immunoreactivity was identified within atherosclerotic plaques (arrows) in both saline- (a) and Ang II-treated (b) aortas. The inset in panel (a) shows that pre-existing elastic lamina disruptions (arrowheads) can be found underneath the plaque before Ang II treatment. (c) In some specimens from the Ang II group, total medial breakage (arrowheads) in association with localized MMP-9 expression (arrows) was observed before haematoma formation, which may represent a precursor of the pseudoaneurysm. (d) MMP-9 was also highly expressed in the thrombi (*) inside the sac of pseudoaneurysms. Scale bars=50 μm (a–c) and 20 μm (d). (e) Quantitation of the intensity of MMP-9 immunoreactivity in the non-ruptured part of the suprarenal abdominal aorta using an arbitrary score (S, saline; A, Ang II; V, antioxidant vitamins; data are mean±s.e.mean. *P<0.05 vs saline, n=6–9). (f) Gelatin zymography and quantitative optical density data of the (pro)MMP-9 activity in the plasma (mean±s.e.mean. n=5–6). Ang II, Angiotensin II.

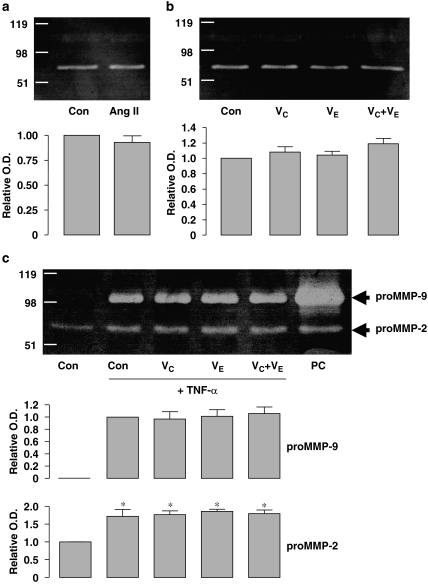

Effects of antioxidants on matrix metalloproteinase-9 release from U937 mononuclear cells in vitro

To examine further the effects of antioxidants on MMP-9 production, we performed zymography analysis with the conditioned medium from differentiated human U937 cells treated with Ang II (100 nM) or TNF-α (20 ng ml−1) for 24 h, neither of which induced cell death, as examined by the Trypan blue exclusion test. MMP-9 gelatinase activity could not be detected with unstimulated cells and Ang II per se did not stimulate MMP-9 release (Figure 4a). Nor did vitamin C (1 mM), vitamin E (10 μM), or their combination, have any effect (Figure 4b). Treatment with TNF-α induced significant proMMP-9 release from U937 cells, whereas antioxidants did not have any effect on TNF-α-induced proMMP-9 (Figure 4c). The concentration of vitamin E used (that is, 10 μM) has been shown to block Ang II-induced oxidative stress and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression in human coronary artery endothelial cells (Mehta et al., 2002). On the other hand, we could detect weak MMP-2 activity in the conditioned media from unstimulated U937 cells (Figures 4a–c), consistent with previous observations (Lopez-Boado et al., 2000). TNF-α, but not Ang II, enhanced MMP-2 production (Figures 4a and c). Similarly, co-treatment with antioxidants had no effect on MMP-2 production either in the absence or presence of TNF-α (Figures 4b and c).

Figure 4.

Effects of Ang II, TNF-α and antioxidant vitamins on matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) release from cultured U937 mononuclear cells. (a and b) Gelatin zymography showing the MMP activity of the conditioned media after a 24-h treatment with vehicle (Con), Ang II (100 nM), vitamin C (VC, 1 mM), vitamin E (VE, 10 μM) or VC+VE. The bands at ∼70 kDa represent the proMMP-2 activity. MMP-9 activity could not be detected under these conditions. Quantitative optical density data are shown below (n=3). (c) Zymography showing that TNF-α (20 ng ml−1 for 24 h) induced proMMP-9 (∼98 kDa) release and enhanced the proMMP-2 activity from U937 cells. Co-treatment with antioxidants had no effect on TNF-α-induced MMP production. *P<0.05 vs control (Con), n=3. Cells treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, 10 ng ml−1) was used as positive control (PC). Ang II, Angiotensin II.

Antioxidants do not improve renal function during Ang II infusion

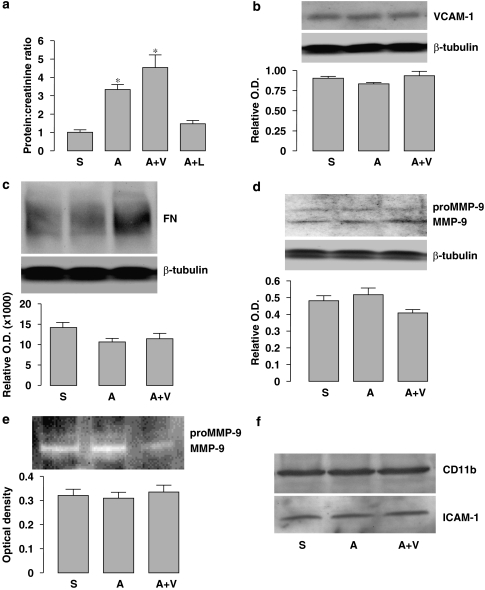

To determine whether antioxidants have beneficial effects on renal function during Ang II infusion, we examined proteinuria in the aged ApoE0 mice. As shown in Figure 5a, the urine protein/creatinine ratio was significantly elevated in the Ang II group as compared to the saline group, while co-treatment with antioxidants had a little effect on Ang II-induced proteinuria (AV group). The protein/creatinine ratio in the Ang II plus losartan group was not significantly different from the saline group. We next assessed the inflammatory response in the kidney by measuring expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and the fibrotic process by measuring fibronectin, and MMP-9 expression and activity. As shown in Figures 5b–e, these parameters were not significantly different among saline, Ang II and Ang II plus antioxidant vitamin groups. Moreover, we did not find evidence that the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 or CD11b, another two markers of inflammation, were changed by these treatments (Figure 5f). These results indicate that inflammation and fibrosis did not appear to have a major role in Ang II-induced renal damage.

Figure 5.

Effects of Ang II and antioxidant co-treatment on renal parameters. (a) Protein to creatinine ratio measured in urine samples from different groups. *P<0.05 vs S, n=5–7. (b–d) Western blot analyses for the expression of VCAM-1, fibronectin (FN) and (pro)MMP-9 in the total protein extracts of kidney. The level of β-tubulin was used to normalize the protein load. Quantitative densitometry data (target to β-tubulin ratio) are shown below each blot. (e) Gelatin zymography and quantitative optical density data of the (pro)MMP-9 activity in kidney homogenates. (f) Western blots of CD11b and ICAM-1 expression in the kidney. Example from two separate experiments. S, saline; A, Ang II; V, antioxidant vitamins; L, losartan. Ang II, Angiotensin II; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.

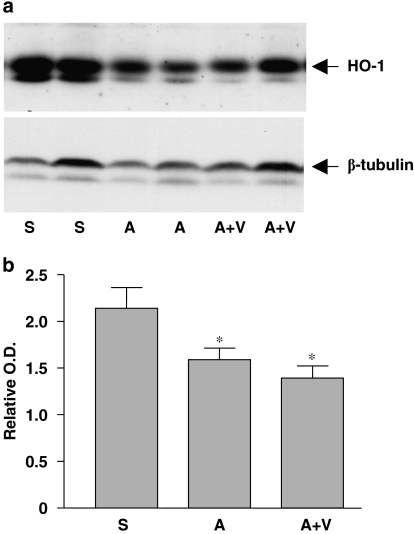

Angiotensin II decreased haeme oxygenase-1 expression in the kidney

Attempting to elucidate the mechanism of Ang II-induced renal damage in the present study, we measured expression of the antioxidant enzyme haeme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), which has been shown to have potent renal protective actions (Bhaskaran et al., 2003; Quan et al., 2004). Unexpectedly, we found that Ang II treatment significantly reduced HO-1 expression in the kidney, but this change was not affected by co-treatment with antioxidants (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Expression of HO-1 in kidneys from saline (S)-, Ang II (A)- and Ang II plus antioxidant vitamins (A+V)-treated mice. (a) Western blot of HO-1. (b) Quantitation of the western blot by densitometry. Data are expressed as HO-1 to β-tubulin ratio. *P<0.05 vs S, n=9–11. Ang II, Angiotensin II; HO-1, haeme oxygenase-1.

Discussion and conclusions

Antioxidant vitamin treatment has been reported to reduce the incidence of Ang II-induced aneurysm formation in the abdominal aorta of ApoE0 mice (Gavrila et al., 2005). In this study, we extended this by examining whether the protective effects of the antioxidants are preserved in aged ApoE0 mice. In contrast to the findings in younger animals, we could not observe a significant protective effect of combined vitamin C+vitamin E treatment on Ang II-induced aortic rupture in older mice. The lack of benefit from the antioxidant treatment cannot be attributed to the doses of the antioxidants, for these are similar to those used in previous studies, and their antioxidant actions were demonstrated by the decreased lipid peroxidation product MDA, in both plasma and kidney homogenates. In this study, we did not utilize the lumen size or external aortic diameter as measurements of AAA development. Our histological study clearly demonstrated that the increased lumen size after aortic rupture was the result of the formation of a pseudolumen, which was composed of the ruptured aortic wall and part of the inflammatory adventitia (Saraff et al., 2003). The size of the resulting lumen is likely to be determined by the initial gap on the aortic wall, the size of the thrombus and the strength of the adventitia, rather than by true aneurysmal dilatation of the aortic wall. Moreover, the increased external aortic diameter could be further complicated by the thickened media or adventitia (Martin-McNulty et al., 2003). In our experiments, however, we could only occasionally find true aneurysmal dilatations along the aortic tree that are pathologically similar to human AAA. Thus we argue that, at least in older animals, the aortic rupture (pseudoaneurysm) induced by Ang II appears to be a binary event, and measures of the lumen or aortic diameter might not precisely reflect the development of AAA. In a pilot study, we infused Ang II in younger animals (26–30-week old). Out of the eight animals treated, we only found two that developed the bulbous form of abdominal aortic rupture. This low incidence made it difficult to directly compare the drug effects in younger and aged animals.

The pathogenesis of Ang II-induced aortic rupture in ApoE0 mice is poorly understood. In some specimens, we identified total medial ruptures without pseudoaneurysm formation, which may represent a precursor of the intramural haematoma (Figure 3c). These lesions were always in association with lipid-rich plaques, where MMP-9 was highly expressed, suggesting that MMP-mediated proteolytic activity may be involved in Ang II-induced aortic rupture. This notion is supported by the finding that pharmacological inhibition of MMP activity reduced the incidence of AAA in Ang II-treated ApoE0 mice (Manning et al., 2003). We have previously demonstrated that internal elastic lamina breakages can be readily identified under atherosclerotic lesions at different stages in ApoE0 mice (Jones et al., 2005). Together with the finding of intense MMP-9 expression in atherosclerotic plaques (Figure 3), our results indicate that disruption of the internal elastic lamina mediated by MMP may be the basis for Ang II-induced aortic rupture. On the other hand, we could not find any pseudoaneurysm formation in old wild-type mice treated with Ang II at the same dose, indicating that high BP alone is not sufficient to induce aortic rupture without pre-existing defects of the aortic wall. Taken together, these observations indicate that pre-existing structural defects in the aortic wall are the prerequisite for Ang II-induced aortic rupture. In this situation, increased BP contributes to the aortic rupture by producing stress failure at the defect in the vessel wall.

Ang II may promote internal elastic lamina disruption by stimulating MMP production in the arterial wall, and vascular smooth muscle cells may be involved (Browatzki et al., 2005). In contrast, our immunohistochemistry study revealed that most of the MMP-9 immunoreactivity in the mouse abdominal aorta was localized in the atherosclerotic plaques, suggesting that the infiltrating macrophages may be an important source of MMP-9. We found a little information on whether Ang II can directly modulate MMP production from macrophages, although there is evidence that Ang II may be involved in modulating cytokine release from these cells (Hahn et al., 1994). We have now studied the effects of Ang II on MMP production in differentiated U937 macrophage-like cells, but found that Ang II had a little direct effect on the release of proMMP-2 or proMMP-9 from U937 cells, leaving open the possibility of a paracrine mechanism responsible for the enhanced aortic MMP production after Ang II infusion. For example, Ang II has been shown to enhance the expression of the proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 and TNF-α, from vascular cells (Arenas et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005), and we showed that TNF-α significantly enhanced both proMMP-9 and proMMP-2 production from U937 cells, consistent with the reports of others (Rahat et al., 2006). However, co-treatment with antioxidant vitamins had no effect on TNF-α-stimulated MMP production in U937 cells. To our knowledge, this is the first direct assessment of the pharmacological effects of vitamin C and vitamin E on MMP release in cultured monocytes, whereas the effects of antioxidant vitamins on MMP production in vascular cells have been reported previously, and the results appeared inconsistent (Morin et al., 1999; Offord et al., 2002). Taken together, we suggest that Ang II-induced pseudoaneurysm formation in the abdominal aorta of old ApoE0 mice is a combined result of pre-existing structural defects (for example, internal elastic lamina breakages), enhanced extracellular matrix degradation and increased wall tension because of elevated BP. Antioxidant therapy alone appears to be insufficient to block Ang II-induced aortic remodeling in aged animals.

The renin–angiotensin system has an important role in the development of renal dysfunction secondary to many diseases (Remuzzi et al., 2005). It has been suggested that Ang II causes renal damage through multiple biological processes, including systemic and glomerular haemodynamic alterations, endothelial dysfunction, interstitial fibrosis and proinflammatory effects (Brewster and Perazella, 2004). However, the molecular pathways underlying these effects remain largely unidentified. Recent evidence suggests that oxidative stress may be involved in mediating Ang II-induced renal injuries in chronic kidney disease (Agarwal et al., 2004). In line with this notion, it has been shown that Ang II infusion in normal rats increased kidney oxidative stress and proteinuria, and decreased creatinine clearance (Haugen et al., 2000). Studies in spontaneously hypertensive rats demonstrated that dietary supplementation with an antioxidant-cocktail reduced renal tissue damage, including leukocyte infiltration and nitrotyrosine abundance, indicating that suppressing oxidative stress may have potential renal protective effects (Rodriguez-Iturbe et al., 2003). However, a little is known on whether antioxidant supplementation can modulate renal damage induced by exogenous Ang II treatment. In this study, we found that basal proteinuria was present in the old ApoE0 mice even under control conditions. This is consistent with the observation that this hyperlipidemic model exhibited obvious renal damage prior to any exogenous interventions (Wen et al., 2002). Ang II infusion significantly increased oxidative stress and proteinuria, while combined vitamin E and vitamin C treatment normalized the Ang II-induced oxidative stress, but had a little effect on Ang II-induced proteinuria. These data suggest that blocking oxidative stress could not antagonize the renal damage induced by exogenous Ang II in these old animals. On the other hand, our study also indicates that it is necessary to examine whether there is a beneficial effect of antioxidants on Ang II-induced renal injury in animal models of younger age.

These results indicate that Ang II-induced proteinuria in this animal model were unlikely to be directly mediated by reactive oxygen species production. In addition, we did not find that Ang II increased markers of inflammation, fibrosis or extracellular matrix degradation. Moreover, it was demonstrated that Ang II-induced proteinuria in rats could be independent of the changes in BP (Park et al., 2000). Interestingly, we found that in kidneys form Ang II-treated rats, the expression of HO-1 was decreased compared to that in kidneys from saline-treated rats. This observation is in contrast to those from experiments in normal wild-type animals (Aizawa et al., 2000; Wesseling et al., 2005), in which administration of Ang II increased HO-1 expression. This discrepancy might be because of the increased basal HO-1 expression in the old hyperlipidemic mice resulted from the increased oxidative stress in the kidney (our unpublished observations). HO-1 exhibits protective effects in multiple aspects of Ang II-induced renal injury, including oxidative stress (Quan et al., 2004; Vera et al., 2007), interstitial fibrosis and inflammation (Pradhan et al., 2006) and tubular epithelial cell apoptosis (Bhaskaran et al., 2003). Therefore, HO-1 induction may represent an endogenous defence reaction to protect renal damage. Suppressed HO-1 expression may exacerbate renal dysfunction during Ang II administration; and this may provide an explanation for the observed increase in proteinuria in Ang II-treated ApoE0 mice, although our results cannot establish a causal role of reduced HO-1 in this process. Nevertheless, co-treatment with antioxidants did not show any effect on the reduced HO-1 expression after Ang II administration, indicating that this action of Ang II may be independent of oxidative mechanisms.

In summary, our results indicate that in ApoE0 mice with advanced age, Ang II-induced abdominal aortic rupture is likely to result from pre-existing aortic structural defects, increased plaque-derived MMP-9 production and increased BP. These pathophysiological mechanisms appear to differ from those underlying Ang II-induced AAA formation in younger animals. Antioxidant vitamins had minimal effects on Ang II-induced aortic remodelling and renal damage in the present model of aged mice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Project Grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and Grants-in-Aid from the National Heart Foundation of Australia. GJD also receives a Principal Research Fellowship from NHMRC.

Abbreviations

- AAA

abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- ApoE0

apolipoprotein E-deficient mice

- HO-1

haeme oxygenase-1

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- TNF-α

tumour necrosis factor-α

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Agarwal R, Campbell RC, Warnock DG. Oxidative stress in hypertension and chronic kidney disease: role of angiotensin II. Semin Nephrol. 2004;24:101–114. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizawa T, Ishizaka N, Taguchi J, Nagai R, Mori I, Tang SS, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 is upregulated in the kidney of angiotensin II-induced hypertensive rats: possible role in renoprotection. Hypertension. 2000;35:800–806. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.3.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo M, Welch WJ. Oxidative stress and nitric oxide in kidney function. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2006;15:72–77. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000191912.65281.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas IA, Xu Y, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Davidge ST. Angiotensin II-induced MMP-2 release from endothelial cells is mediated by TNF-alpha. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C779–C784. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00398.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellosta S, Via D, Canavesi M, Pfister P, Fumagalli R, Paoletti R, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors reduce MMP-9 secretion by macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:1671–1678. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.11.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskaran M, Reddy K, Radhakrishanan N, Franki N, Ding G, Singhal PC. Angiotensin II induces apoptosis in renal proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F955–F965. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00246.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster UC, Perazella MA. The renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system and the kidney: effects on kidney disease. Am J Med. 2004;116:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browatzki M, Larsen D, Pfeiffer CA, Gehrke SG, Schmidt J, Kranzhofer A, et al. Angiotensin II stimulates matrix metalloproteinase secretion in human vascular smooth muscle cells via nuclear factor-kappaB and activator protein 1 in a redox-sensitive manner. J Vasc Res. 2005;42:415–423. doi: 10.1159/000087451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron E, Liautard JP, Kohler S. Differentiated U937 cells exhibit increased bactericidal activity upon LPS activation and discriminate between virulent and avirulent Listeria and Brucella species. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56:174–181. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty A, Manning MW, Cassis LA. Angiotensin II promotes atherosclerotic lesions and aneurysms in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1605–1612. doi: 10.1172/JCI7818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrila D, Li WG, McCormick ML, Thomas M, Daugherty A, Cassis LA, et al. Vitamin E inhibits abdominal aortic aneurysm formation in angiotensin II-infused apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1671–1677. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000172631.50972.0f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guron GS, Grimberg ES, Basu S, Herlitz H. Acute effects of the superoxide dismutase mimetic tempol on split kidney function in two-kidney one-clip hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2006;24:387–394. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000200511.02700.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn AW, Jonas U, Buhler FR, Resink TJ. Activation of human peripheral monocytes by angiotensin II. FEBS Lett. 1994;347:178–180. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna IR, Taniyama Y, Szocs K, Rocic P, Griendling KK. NAD(P)H oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species as mediators of angiotensin II signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4:899–914. doi: 10.1089/152308602762197443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen EN, Croatt AJ, Nath KA. Angiotensin II induces renal oxidant stress in vivo and heme oxygenase-1 in vivo and in vitro. Kidney Int. 2000;58:144–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Jones GT, Husband AJ, Dusting GJ. Cardiovascular protective effects of synthetic isoflavone derivatives in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Vasc Res. 2003;40:276–284. doi: 10.1159/000071891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Roberts SJ, Datla S, Dusting GJ. NO modulates NADPH oxidase function via heme oxygenase-1 in human endothelial cells. Hypertension. 2006;48:950–957. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000242336.58387.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GT, Jiang F, McCormick SP, Dusting GJ. Elastic lamina defects are an early feature of aortic lesions in the apolipoprotein E knockout mouse. J Vasc Res. 2005;42:237–246. doi: 10.1159/000085553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Boado YS, Wilson CL, Hooper LV, Gordon JI, Hultgren SJ, Parks WC. Bacterial exposure induces and activates matrilysin in mucosal epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:1305–1315. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.6.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning MW, Cassis LA, Daugherty A. Differential effects of doxycycline, a broad-spectrum matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor, on angiotensin II-induced atherosclerosis and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:483–488. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000058404.92759.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-McNulty B, Tham DM, da Cunha V, Ho JJ, Wilson DW, Rutledge JC, et al. 17 beta-estradiol attenuates development of angiotensin II-induced aortic abdominal aneurysm in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1627–1632. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000085842.20866.6A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May JM, Qu ZC, Mendiratta S. Protection and recycling of alpha-tocopherol in human erythrocytes by intracellular ascorbic acid. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;349:281–289. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta JL, Li DY, Yang H, Raizada MK. Angiotensin II and IV stimulate expression and release of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in cultured human coronary artery endothelial cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2002;39:789–794. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200206000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller FJ, Jr, Sharp WJ, Fang X, Oberley LW, Oberley TD, Weintraub NL. Oxidative stress in human abdominal aortic aneurysms: a potential mediator of aneurysmal remodeling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:560–565. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000013778.72404.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin I, Li WQ, Su S, Ahmad M, Zafarullah M. Induction of stromelysin gene expression by tumor necrosis factor alpha is inhibited by dexamethasone, salicylate, and N-acetylcysteine in synovial fibroblasts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:1634–1640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagami H, Takemoto M, Liao JK. NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide anion mediates angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:851–859. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahashi TK, Hoshina K, Tsao PS, Sho E, Sho M, Karwowski JK, et al. Flow loading induces macrophage antioxidative gene expression in experimental aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:2017–2022. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000042082.38014.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Fushimi K, Kouchi H, Mihara K, Miyazaki M, Ohe T, et al. Inhibitory effects of antioxidants on neonatal rat cardiac myocyte hypertrophy induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and angiotensin II. Circulation. 1998;98:794–799. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.8.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offord EA, Gautier JC, Avanti O, Scaletta C, Runge F, Kramer K, et al. Photoprotective potential of lycopene, beta-carotene, vitamin E, vitamin C and carnosic acid in UVA-irradiated human skin fibroblasts. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:1293–1303. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00831-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JK, Muller DN, Mervaala EM, Dechend R, Fiebeler A, Schmidt F, et al. Cerivastatin prevents angiotensin II-induced renal injury independent of blood pressure- and cholesterol-lowering effects. Kidney Int. 2000;58:1420–1430. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan A, Umezu M, Fukagawa M. Heme-oxygenase upregulation ameliorates angiotensin II-induced tubulointerstitial injury and salt-sensitive hypertension. Am J Nephrol. 2006;26:552–561. doi: 10.1159/000098001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prisant LM, Mondy JS., III Abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2004;6:85–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2004.02838.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pueyo ME, Gonzalez W, Nicoletti A, Savoie F, Arnal JF, Michel JB. Angiotensin II stimulates endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 via nuclear factor-kappaB activation induced by intracellular oxidative stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:645–651. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.3.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan S, Yang L, Shnouda S, Schwartzman ML, Nasjletti A, Goodman AI, et al. Expression of human heme oxygenase-1 in the thick ascending limb attenuates angiotensin II-mediated increase in oxidative injury. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1628–1639. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahat MA, Marom B, Bitterman H, Weiss-Cerem L, Kinarty A, Lahat N. Hypoxia reduces the output of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) in monocytes by inhibiting its secretion and elevating membranal association. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:706–718. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0605302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remuzzi G, Perico N, Macia M, Ruggenenti P. The role of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system in the progression of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005. pp. S57–S65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Zhan CD, Quiroz Y, Sindhu RK, Vaziri ND. Antioxidant-rich diet relieves hypertension and reduces renal immune infiltration in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2003;41:341–346. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000052833.20759.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraff K, Babamusta F, Cassis LA, Daugherty A. Aortic dissection precedes formation of aneurysms and atherosclerosis in angiotensin II-infused, apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1621–1626. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000085631.76095.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh K. Serum lipid peroxide in cerebrovascular disorders determined by a new colorimetric method. Clin Chim Acta. 1978;90:37–43. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(78)90081-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupp M, Lee LD, Frost N, Umbreen S, Schmidt B, Unger T, et al. Regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activity by losartan metabolites. Hypertension. 2006;47:586–589. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000196946.79674.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K, Bonaa KH, Jacobsen BK, Bjork L, Solberg S. Prevalence of and risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms in a population-based study: the Tromso study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:236–244. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slot C. Plasma creatinine determination. A new and specific Jaffe reaction method. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1965;17:381–387. doi: 10.3109/00365516509077065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stulak JM, Lerman A, Porcel MR, Caccitolo JA, Romero JC, Schaff HV, et al. Renal vascular function in hypercholesterolemia is preserved by chronic antioxidant supplementation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:1882–1891. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1291882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanifuji C, Suzuki Y, Geot WM, Horikoshi S, Sugaya T, Ruiz-Ortega M, et al. Reactive oxygen species-mediated signaling pathways in angiotensin II-induced MCP-1 expression of proximal tubular cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1261–1268. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Gavrila D, McCormick ML, Miller FJ, Jr, Daugherty A, Cassis LA, et al. Deletion of p47phox attenuates angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm formation in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2006;114:404–413. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.607168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma R, Garrick R, McClung J, Frishman WH. Chronic renal dysfunction as an independent risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease. Cardiol Rev. 2005;13:98–107. doi: 10.1097/01.crd.0000132600.45876.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri ND. Roles of oxidative stress and antioxidant therapy in chronic kidney disease and hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2004;13:93–99. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200401000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera T, Kelsen S, Yanes LL, Reckelhoff JF, Stec DE. Ho-1 induction lowers blood pressure and superoxide production in the renal medulla of Angiotensin Ii hypertensive mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R1472–R1478. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00601.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen M, Segerer S, Dantas M, Brown PA, Hudkins KL, Goodpaster T, et al. Renal injury in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Lab Invest. 2002;82:999–1006. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000022222.03120.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesseling S, Ishola DA, Jr, Joles JA, Bluyssen HA, Koomans HA, Braam B. Resistance to oxidative stress by chronic infusion of angiotensin II in mouse kidney is not mediated by the AT2 receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F1191–F1200. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00322.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Ma Y, Zhang J, Cheng J, Du J. A new cellular signaling mechanism for angiotensin II activation of NF-kappaB: an IkappaB-independent, RSK-mediated phosphorylation of p65. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1148–1153. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000164624.00099.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]