Abstract

This article presents results from the first survey of California local health jurisdictions (LHJs) subsequent to passage of legislation that allows for over-the-counter pharmacy sales of syringes. In 2004 Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed Senate Bill 1159 (SB1159) into law to “prevent the spread of HIV, hepatitis and other blood-borne disease among drug users, their sexual partners and their children.” This legislation permits counties and cities to authorize a local disease prevention demonstration project (DPDP). Once authorized, a DPDP permits individuals to legally purchase and possess up to ten syringes from registered pharmacies without a doctor’s prescription. From June to August 2005, we surveyed health departments in all 61 LHJs to assess implementation status of SB1159. Fifty-seven (93%) LHJs responded. Nine (16%) had approved a DPDP by August 2005, 17 (30%) were in the process of obtaining authorization, and 18 (32%) anticipated that SB1159 would never be authorized in their LHJ. Among LHJs that do not plan to approve a DPDP (n = 18), the reasons included: strong community opposition (41%), competing priorities (35%), law enforcement opposition (29%), and little or no interest among pharmacies (29%). In LHJs that have authorized a DPDP, 31.4% of pharmacies registered to legally sell nonprescription syringes. Preliminary results indicate that local coalitions, comprised of public health, waste management and pharmacy officials, have been instrumental in facilitating DPDP authorization. Further research is needed to identify facilitators and barriers to adopting SB1159, to identify areas for improving technical assistance to implementers, and to assess the public health impact of the legislation.

Keywords: Health policy, HIV/AIDS, Injection drug use, Pharmacies, Sterile syringe access.

Background

In California, injection drug use is associated with 19% of cumulative AIDS cases,1 and it is estimated that over 1,500 incident HIV cases are attributed to injection drug use annually.2 An estimated 600,000 Californians are infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) with approximately 5,000 incident cases occurring annually.3 At least 60% of prevalent HCV cases and nearly all incident cases are attributed to injection drug use.4 Interventions to prevent blood-borne infections among IDUs attempt to decrease the use of non-sterile syringes.

In response to the AIDS epidemic, a number of states throughout the USA have introduced legislation to permit over-the-counter (OTC) sales of pharmacy syringes.5–9 Pharmacy syringe sales have been associated with reduced rates of syringe sharing10,11 and reduced rates of HIV infection among injection drug users (IDUs).12,13 OTC syringe sales offer the potential for enhancing syringe availability based on the broad distribution of pharmacies throughout most regions of the USA and extended hours of operation.8,11,14 IDUs in many locations perceive pharmacies as stable, safe and affordable sources of sterile syringes.15,16 In states where legislation has permitted the statewide sale of OTC syringes,7,17,18 a large percentage of pharmacists have agreed to sell syringes,19,20 and some have run syringe exchange programs (SEPs) in their stores.21 In 1993, 83% of pharmacies were found to sell OTC syringes within the five largest cities of Connecticut. During the same time period, IDUs reported that their syringe purchases from pharmacies rose from 19 to 78%.19 In other locations, however, relatively low proportions of IDUs relied on pharmacies for syringes initially, directly after pharmacy access legislation changed,9 yet, over time, more IDUs have begun to rely on pharmacies as a primary source of sterile syringes.10 Pharmacists’ attitudes and beliefs, however, vary considerably and are, at times, detrimental to adequate provision of sterile syringes7,8,22–24 and can lead to decreases in OTC sales.25

In 2004, California became the 45th state to permit OTC syringe sales when Governor Schwarzenegger signed Senate Bill (SB) 1159 (Chapter 608, Statutes of 2004) into law.26 Once approved by the local governing body in each local health jurisdiction (LHJ), this legislation creates a local disease prevention demonstration project (DPDP), a collaboration between pharmacies and public health officials. In LHJs where SB1159 has been authorized, licensed pharmacies must register with their local health department and certify that they will: provide health education materials to syringe purchasing clients, provide at least one option for safe syringe disposal, and store syringes in a location that is only accessible to staff. Once this has occurred, pharmacies are permitted to sell ten or fewer syringes without a prescription. LHJs are required to maintain a list of locally registered pharmacies and to provide written materials that pharmacists, in turn, will give to all syringe-purchasing customers. SB1159 was implemented January 1, 2005, and LHJs that opt in are able to participate in this new intervention until December 31, 2010, when the legislation terminates.

The dual opt-in process of requiring authorization by local health and government officials first, and registration by pharmacies second, makes the California syringe access legislation unique. Additionally, California’s diverse geographic and demographic characteristics present unique questions about the impact that pharmacy access to syringes can have on disease prevention. In preparation for evaluating the impact of SB1159 on IDUs and the community, we conducted a survey of the 61 LHJs to determine the current status and future plans regarding its adoption. This paper provides the first ever data on the response to a public health policy for decreasing blood-borne disease transmission among IDUs when LHJs are permitted to adopt or reject such a policy locally. The paper also provides additional follow-up findings from two LHJs that shed light on the circumstances influencing DPDP approval.

Methods

An LHJ survey was developed in coordination with a statewide evaluation advisory panel which, per SB1159 mandate, was comprised of specialists, representatives, and stakeholders from the state, local public health, pharmacy, law enforcement, and waste management communities. The panel included the caliber of professionals who would ultimately complete the survey, assisting our research team in structuring the survey and data collection methods in a manner that would enhance data quality and response rate.

Between June and August 2005, the survey was sent to all LHJs to learn about the status of SB1159. Surveys were completed by local public health staff and returned to the California Department of Health Services, Office of AIDS (CDHS/OA) via email, fax or US mail. In order to increase the response rate, email and telephone follow-up ensued.

Survey variables of interest for this paper include: SB1159 authorization status, coalition building activities, program implementation characteristics, program coverage, syringe disposal modalities, program financing, local SEP availability, stakeholders educated on SB1159 and technical assistance (TA) received. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).27

Results

Completed surveys were obtained from 57 of 61 (93%) California LHJs (Table 1). The assistance of the evaluation advisory panel and ongoing working relationships between CHDS/OA and LHJs appear to have fostered the favorable response rate. In 19% of the surveyed LHJs, the health officer completed the survey while, in other LHJs, the survey was completed by HIV/AIDS prevention coordinators, program managers and other staff. Among all responding LHJs, 25% had formed a coalition to address implementation procedures. Health officers (23%), HIV/AIDS prevention coordinators (23%) and local Offices of AIDS (11%) reported being primarily responsible for managing progress and implementation of their respective DPDPs. Among LHJs that do not plan to adopt the legislation (n = 18), the principle reasons mentioned for not doing so included: strong community opposition (41%), competing programmatic priorities (35%), strong law enforcement opposition (29%), and little or no interest among pharmacies (29%). By August 2005, the following counties had authorized a DPDP: Alameda, Contra Costa, Los Angeles, Marin, Santa Cruz (unincorporated areas), San Francisco, San Mateo, Yolo, and Yuba. All of these counties, except Yuba, currently have an SEP. Twenty-eight other surveyed LHJs (49%) indicated interest in creating a DPDP.

Table 1.

Status of disease prevention demonstration project approval to allow non-prescription syringe sales among 61 California local health jurisdictions (LHJs) within the first 8 months after passage of a state law allowing LHJs to do so

| Status | Number of LHJs |

|---|---|

| Approved | 9 |

| In process of approving | 9 |

| Plan to approve | 17 |

| Approval process on hold (info gathering stage) | 2 |

| No plans to approve | 18 |

| Status unknown | 2 |

| Did not complete surveya | 4 |

aOne urban and three rural LHJs failed to complete the survey

Subsequent to the signing of SB1159, LHJs have utilized several resources to acquire relevant information about pharmacy access to syringes and creation of a DPDP. Among the 57 surveyed LHJs, 26 (46%) reported that they had received SB1159 TA by the summer of 2005. Among those, 65% reported that they had received TA from other LHJs, 58% had received information from CDHS/OA and 35% had received information from a website hosted by the Center for Health Improvement with content developed by CDHS/OA (www.chipolicy.org).

Thirty-seven LHJs (65%) reported that they had provided education to local stakeholders. Among those, 49% provided education and information to pharmacists, 30% provided education to law enforcement, 30% provided education to SEP staff and participants, and 19% provided education to waste management officials.

As of August 2005, six of the nine LHJs that had adopted SB1159 had registered pharmacies. Overall, 133 pharmacies were registered, representing 31.4% of the 424 pharmacies located in these regions (Table 2), and the registration process varied by LHJ. In some LHJs, pharmacy chains chose to have all of their pharmacies become certified as participating DPDP pharmacies. In others, regional pharmacy chain management left opt-in decisions up to individual stores. A small number of independent pharmacies registered to sell OTC syringes.

Table 2.

Number and percentage of pharmacies registered within local health jurisdictions that have created a disease prevention demonstration project as of August 2005

| LHJ | Number of registered pharmacies | Total number of pharmacies in LHJ | Pharmacies registered (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alameda | 41 | 137 | 30 |

| Contra Costa | 32 | 145 | 22 |

| Marin | 12 | 34 | 35 |

| San Francisco | 35 | 88 | 40 |

| Yolo | 10 | 13 | 78 |

| Yuba | 3 | 7 | 43 |

| Total | 133 | 424 | 31.4 |

SB1159 requires that participating pharmacies provide for safe syringe disposal through one or more of the following options: providing an on-site safe syringe collection and disposal program; furnishing or selling mail-back sharps containers that meet state and federal standards; or, furnishing or selling personal sharps containers. Survey results indicate that each of these options will be utilized. Within LHJs with an authorized DPDP, 50% of the registered pharmacies provided or planned to provide sharps containers with instructions to discard them at locations other than the pharmacy. Thirty percent anticipated having sharps containers returned to the pharmacy and another 30% planned to provide drop boxes for containerized syringes. Finally, 16% planned to provide pre-addressed sharps boxes for discard of syringes through mail and 16% planned to provide drop boxes for loose syringes.

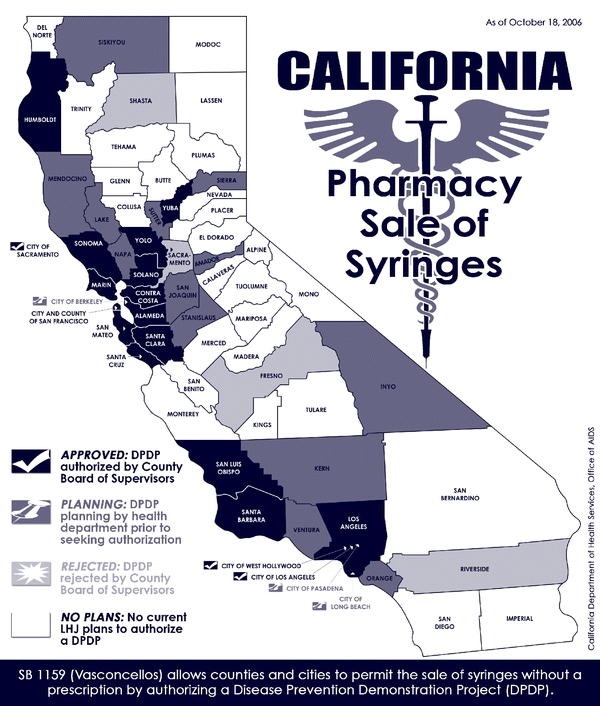

While it is too soon to report systematically on syringe sales rates across the state, follow-up conversations with public health staff who completed the survey provided additional qualitative data. Initially, a relatively small number of IDU customers had attempted to purchase OTC syringes. A modest increase in syringe sales activities has occurred in LHJs that adopted SB1159 early, with pharmacies reporting between two and ten customers weekly and no negative experiences. Some LHJs and pharmacies that had not yet authorized a DPDP reported wanting to observe experiences elsewhere before deciding whether to make OTC syringes available locally. Since August 2005 (subsequent to completion of our survey), six additional LHJs (Santa Clara, Humboldt, Solano, Sonoma, Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo) and one city (Sacramento) authorized DPDPs (see map in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Status of non-prescription pharmacy sales of syringes in California local health jurisdictions* as of July 2006**.

Four LHJs (Sacramento, Riverside, Fresno and Shasta) held votes resulting in rejection of a DPDP. Media accounts highlighted the political process connected to DPDP authorization discussions in Sacramento and Riverside Counties. In Sacramento County, at a Board of Supervisors meeting, the county health officer was given the opportunity to assemble a team of experts to present on the science surrounding enhanced syringe access and disease prevention. The health officer introduced a team of epidemiologists, physicians, public health experts, pharmacists, harm reduction specialists and the dean of the School of Medicine from UC Davis. These experts provided public testimony, citing the scientific literature and their own clinical experiences, demonstrating that enhanced syringe access leads to decreased risk of disease transmission. Three individuals, including a representative of local law enforcement, testified against SB1159. Despite presentation of the scientific evidence in favor of pharmacy sales of syringes, and the support of two of five Sacramento supervisors, one supervisor suggested that she would like to have local city council members discuss and vote on DPDP authorization so that she would be able to better ascertain her constituents’ views. Two other supervisors supported this approach. Subsequently, the health officer, public health experts and community members testified at seven local city council meetings. Ultimately, six of seven city councils in Sacramento County voted against implementation of a DPDP and the County Board of Supervisors voted 3–2 not to authorize a DPDP. Despite the outcome on the county level, the Sacramento City Council voted 7–2 in August 2006 in favor of an ordinance that would allow the city to implement a DPDP. The council also approved a motion by a council member to conduct a study on the feasibility of the city funding a syringe exchange program. The final Sacramento City Council vote on authorization of a syringe exchange program was pending when this article went to press.

In Riverside County, one member of the County Board of Supervisors, who was opposed to SB1159, took a proactive approach to prohibit potential authorization of a DPDP. This supervisor brought forth a vote against authorization of a DPDP soon after SB1159 was enacted.

Discussion

Pharmacy sales of OTC syringes are underway in California. Six months post enactment of SB1159, local DPDPs were authorized in 9 of 61 LHJs. Unlike other states where authorization of OTC sales took place on a statewide level, the law passed in California requires a dual opt-in process whereby LHJs must first approve a DPDP, after which pharmacies must register with the local health department. Preliminary findings from our first LHJ survey indicate that this unique dual opt-in process is functioning well in a number of LHJs where dedicated local coalitions and diverse public health expertise have facilitated nearly seamless implementation procedures. In other LHJs, however, the dual opt-in process has presented challenges that appear to delay and potentially impede implementation. Stakeholders who wish to see a DPDP authorized must first garner local support and second organize around pharmacists, waste management professionals, and law enforcement officials.

Survey results indicate that, in the majority of LHJs (57%), health officers, HIV/AIDS prevention coordinators and local Offices of AIDS are responsible for managing progress and implementation of DPDPs. It is interesting to note that few, if any, DPDP coalitions have enlisted the support of local SEPs. This appears to be an opportunity lost when considering the important insights and experiences that can be shared. Community and law enforcement opposition, perennial barriers to successful risk reduction programs among IDUs, remain as challenges in several LHJs. It will be important to further explore the type and extent of community opposition in subsequent waves of the LHJ survey in order to learn where additional provision of TA may be worthwhile.

In approximately one third of LHJs that do not plan to implement a DPDP, competing programmatic priorities and lack of interest among local pharmacists also have hindered approval. In some LHJs, public health leaders expressed concern that their local health departments are understaffed to provide proper DPDP guidance and supervision. While the customer bares the majority of OTC syringe sales costs, staff time, waste management activities and production of health education materials can present programmatic and budgetary concerns that must be addressed.

Survey results indicate that ongoing SB1159 TA is necessary. Nearly half (46%) of all surveyed LHJs indicated that they received TA during information gathering, contemplation and implementation phases of a local DPDP. Approximately two thirds (65%) of LHJs that received TA indicated that they had received peer-based TA from staff in other LHJs. Public health staff found it useful to interchange ordinance language, health education materials, strategic plans, implementation protocols, and coalition building strategies. CDHS/OA was the second most popular source of SB1159 TA, providing information via presentations, guidance documents and letters, telephone, and email correspondence. TA included information on: legislation content, mandated roles of different stakeholders, scientific literature on syringe access, safe syringe disposal, and HIV/AIDS trends among IDUs. Finally, over one third (35%) of LHJs reported that they received TA and information from a website containing links to information on SB1159. It is anticipated that these three important sources of information and TA will continue to be enhanced to assist LHJs.

Many of the LHJs (65%) have themselves provided education and guidance to DPDP stakeholders. Provision of such TA has been primarily focused on pharmacists, law enforcement departments, SEP staff and participants, and waste management officials. In some LHJs, such education assisted in creating additional DPDP-friendly constituents. In others, it fostered dialogue between key DPDP stakeholders and a better understanding of necessary next steps. While experiences in Sacramento and Riverside Counties indicate that such dialogue may not always lead to authorization of a DPDP, experiences in 15 other LHJs that have successfully authorized DPDPs (9 prior to administration of our survey and 6 after) portray success that may, in part, be tied to successful public health discussions.

By August 2005, participation by pharmacies in local DPDPs was relatively modest. Approximately one third of eligible pharmacies in the counties that had approved a DPDP had registered to participate. It is anticipated that the number of registered pharmacies will continue to increase as more LHJs authorize DPDPs. Chain pharmacies appear to comprise the bulk of pharmacies that have opted in. It is important to note that previous research in other states found that independent pharmacies were more likely to sell OTC syringes and did so at lower costs to customers.7,8 In light of such findings, it may be prudent for public health officials to encourage registration of independent pharmacies.

Experiences in Sacramento and Riverside Counties, where the Board of Supervisors voted not to authorize a DPDP, highlight the fact that the community organizing and marshalling of political resources that has been done at the state level in other states across the USA must be done on the local level in California. It is at the local level that opposition, from the community and law enforcement, is at its strongest, and the financial benefits are at their weakest. If in a small city, for instance, the city incurs no expenses in maintaining the health of individuals with HIV and HCV (because the county subsidizes these costs), and perceives risk to public safety with the authorization of OTC syringe sales, the motivation to participate in a DPDP is drastically reduced.

During the DPDP authorization process in several LHJs, it became evident that syringe disposal protocols and costs created barriers to authorization. Currently, California lacks statewide standards on household sharps disposal. With the advent of SB1159 and local DPDPs, numerous sharps disposal discussions have occurred and a variety of strategies have been employed to address concerns surrounding inadequate disposal of non-sterile syringes. In one DPDP, the authorizing LHJ has added a surcharge to the price of a 10-pack of syringes to cover costs of sharps disposal. In other LHJs, syringe disposal costs have been integrated into existing waste management systems and, in others, the local health department subsidizes syringe disposal. As with other harm reduction programs, there does not appear to be a one-size fits all approach to syringe disposal. Future research is needed to explore the efficiency, effectiveness, and acceptability of the various DPDP syringe disposal modalities.

From a research perspective, the heterogeneous manner in which LHJs are responding to the law creates a unique opportunity to examine LHJs before and after implementation of the law, and compare LHJs that do and do not approve a DPDP. This pilot survey will be revised and repeated on an annual basis to create a registry for monitoring the status of DPDPs throughout the state to identify factors associated with local adoption of SB1159. These data will be essential for defining the primary exposure variable to evaluate the impact of DPDPs on IDU behaviors.

Conclusion

This study provides the first ever data on the response to a public health policy (SB1159) for decreasing blood-borne disease transmission among IDUs when LHJs are permitted to adopt or reject such a policy. California’s dual opt-in approach to legalizing OTC syringe sales has led to a measured response by LHJs, rather than an overwhelming decision statewide to create DPDPs. While many LHJs have chosen not to create DPDPs, others are waiting to see the impact in neighboring LHJs before moving ahead. TA is important for aiding county health officials, pharmacists, law enforcement, and other stakeholders in making this decision and will continue to be needed throughout the implementation process within LHJs that adopt a DPDP. Future studies, combining the results of additional LHJ surveys with geopolitical measures, census data, infectious disease and crime statistics, will be conducted to identify correlates of DPDP approval.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the California SB1159 Evaluation Advisory Panel which provided helpful guidance and feedback on the LHJ Survey Instrument and overall evaluation activities. We also wish to thank John Keasling for creation of the California Pharmacy Sales of Syringes Map and Shante Brown for assistance with data entry. Finally, we wish to acknowledge the assistance of the California Conference on Local Health Officers, The California Conference of Local AIDS Directors, the California Health Executives Association of California, and all LHJ staff who took the time to complete the SB1159 survey.

Footnotes

Stopka, Ross, and Truax are with the Office of AIDS, California Department of Health Services, Sacramento, CA, USA; Garfein is with the School of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA.

References

- 1.California Department of Health Services Office of AIDS. Cumulative AIDS case data through January 31, 2006. Accessed on March 7, 2006. Available at: http://www.dhs.ca.gov/aids/Statistics/pdf/Stats2006/Jan06AIDSmerged.pdf.

- 2.Facer MS, Ritieni A, Marino J, et al. Consensus Meeting on HIV/AIDS Incidence and Prevalence in California. Sacramento: California Department of Health Services; 2001.

- 3.California Department of Health Services. The Hepatitis C Strategic Plan. A Collaborative Approach to the Emerging Epidemic in California. Sacramento: Disease Investigations and Surveillance Branch, Hepatitis C Prevention and Control Unit; 2001.

- 4.Williams IT. Epidemiology of hepatitis C in the United States. Am J Med. 1999;107:2S–9S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Burris S, Vernick J, Ditzler A, Strathdee S. The legality of selling or giving syringes to injection drug users. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2002;42(Suppl 2):S13–S18. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Singer M, Baer H, Scott G, Horowitz S, Weinstein B. Pharmacy access to syringes among injection drug users: follow-up findings from Hartford, Connecticut. Public Health Rep. 1998;113(Suppl 1):81–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Compton WM, Horton JC, Cottler LB, et al. A multistate trial of pharmacy syringe purchase. J Urban Health. 2004;81:661–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Stopka TJ, Singer M, Teng W, et al. Pharmacy access to over-the-counter syringes in Connecticut: implications for HIV and hepatitis prevention among injection drug users. AIDS Public Policy J. 2002;17:115–126.

- 9.Fuller CM, Ahern J, Vadnai L, et al. Impact of increased syringe access: preliminary findings on injection drug user syringe source, disposal, and pharmacy sales in Harlem, New York. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2002;42(Suppl 2):S77–S82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Pouget ER, Deren S, Fuller CM, et al. Receptive syringe sharing among injection drug users in Harlem and the Bronx during the New York State expanded syringe access demonstration program. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:471–477. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Wodak A, Cooney A. Do needle syringe programs reduce HIV infection among injecting drug users: a comprehensive review of the international evidence. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41:777–813. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Friedman SR, Perlis T, Des Jarlais DC. Laws prohibiting over-the-counter syringe sales to injection drug users: relations to population density, HIV prevalence, and HIV incidence. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:791–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Holmberg SD. The estimated prevalence and incidence of HIV in 96 large U.S. metropolitan areas. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:642–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Jones TS, Coffin PO. Preventing blood-borne infections through pharmacy syringe sales and safe community syringe disposal. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2002;42(Suppl 2):S6–S9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Reich W, Compton WM, Horton JC, et al. Injection drug users report good access to pharmacy sale of syringes. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2002;42(Suppl 2):S68–S72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Junge B, Vlahov D, Riley E, Huettner S, Brown M, Beilenson P. Pharmacy access to sterile syringe for injection drug users: attitudes of participants in a syringe exchange program. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash.). 1999;39:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Valleroy LA, Weinstein B, Jones TS, Groseclose SL, Rolfs RT, Kassler WJ. Impact of increased legal access to needles and syringes on community pharmacies’ needle and syringe sales—Connecticut, 1992–1993. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1995;10:73–81. [PubMed]

- 18.Wright-De Aguero L, Weinstein B, Jones TS, Miles J. Impact of change in Connecticut syringe prescription laws on pharmacy sales and pharmacy managers’ practices. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1998;18(Suppl 1):102–110. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Groseclose SL, Weinstein B, Jones T, et al. Impact of increased legal access to needles and syringes on practices of injecting-drug users and police officers—Connecticut, 1992–1993. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1995;10:82–89. [PubMed]

- 20.Singer M, Himmelgreen D, Weeks MR, Radda KE, Martinez R. Changing the environment of AIDS risk: findings on syringe and pharmacy sales of syringes in Hartford, Connecticut. Med Anthropol. 1997;18:107–130. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Riley ED, Safaeian M, Strathdee SA, et al. Comparing new participants of a mobile versus a pharmacy-based needle exchange program. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24:57–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Farley TA, Niccolai LM, Billeter M, Kissinger PJ, Grace M. Attitudes and practices of pharmacy managers regarding needle sales to injection drug users. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1999;39:23–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Gleghorn AA, Gee G, Vlahov D. Pharmacists’ attitudes about pharmacy sale of needles/syringes and needle exchange programs in a city without needle/syringe prescription laws. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1998;18(Suppl 1):89–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Reich W, Compton WM, Horton JC, et al. Pharmacist ambivalence about over-the-counter sale of syringes to injection drug users. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2002;42(Suppl 2):S52–S57. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Singer M, Stopka T. Diminishing access to over-the-counter (OTC) syringes among injection drug users in Hartford, CT: A longitudinal assessment. Paper presented at 3rd Annual CIRA Science Day. September 21, 2000. Yale University, Dept. of Epidemiology and Public Health. New Haven, Connecticut.

- 26.Legislative Counsel. State of California. Official California Legislative Information. Accessed on August 16, 2006. Available at: http://www.leginfo.ca.gov.

- 27.SPSS Inc. SPSS Base 13.0 for Windows User’s Guide. Chicago, Illinois: SPSS Inc.; 2004.