Abstract

A systematic literature review was undertaken to assess the effectiveness of interventions that aim to prevent back pain and back injury in nurses. Ten relevant databases were searched; these were examined and reference lists checked. Two reviewers applied selection criteria, assessed methodological quality and extracted data from trials. A qualitative synthesis of evidence was undertaken and sensitivity analyses performed. Eight randomised controlled trials and eight non‐randomised controlled trials met eligibility criteria. Overall, study quality was poor, with only one trial classified as high quality. There was no strong evidence regarding the efficacy of any interventions aiming to prevent back pain and injury in nurses. The review identified moderate level evidence from multiple trials that manual handling training in isolation is not effective and multidimensional interventions are effective in preventing back pain and injury in nurses. Single trials provided moderate evidence that stress management programs do not prevent back pain and limited evidence that lumbar supports are effective in preventing back injury in nurses. There is conflicting evidence regarding the efficacy of exercise interventions and the provision of manual handling equipment and training. This review highlights the need for high quality randomised controlled studies to examine the effectiveness of interventions to prevent back pain and injury in nursing populations. Implications for future research are discussed.

Keywords: nurses, back pain, back injuries, intervention studies, review

Nurses play an important role within the health care system, providing and assisting in the provision of primary, secondary and tertiary level health care. Typically, their work is physically demanding. Nurses frequently assist patients to mobilise, transfer between positions and perform other activities of daily living such as toileting and showering.

Nurses have an increased risk of back trouble. Compared with other professions, they have an increased risk of back pain1 and a six times higher prevalence of back injury.2 Nurses and related medical workers lead all other occupations for risk of herniated lumbar intervertebral discs requiring hospitalisation in women.3 Furthermore, hospitals and nursing and residential care facilities lead all industries for workplace injury and illness.4

Numerous factors have been found to increase nurses' risk of back pain.5 Physical load and work posture play a role, as do psychosocial factors such as personality and the presence of psychosomatic symptoms. Work task and work organisational factors have been shown to be significant risks in individual studies, although when all trials are considered the evidence is inconsistent. Nursing qualifications are important, with nursing assistants at greater risk for back pain than registered nurses. Years in the nursing profession may also be relevant, with a growing body of evidence suggesting that younger nurses are at greatest risk.5 Identification of individual physical predictors of back pain is more elusive. Prospective studies find predominantly non‐significant relationships or inconsistent results.6,7,8,9,10 However, reduced lateral bending of the spine has been identified as a risk factor in two studies.11,12

Back pain and injury have a major impact on the efficiency of the nursing workforce. Registered nurses rank seventh and nursing aides and orderlies are highest ranked across all occupations for back injuries involving days away from work in private industry.13 Back injuries and resultant workers' compensation claims in nurses are expensive. In long‐term care facilities in the United States, nurses' back injuries are estimated to cost over US$6 million in indemnity and medical payments. Nurses' compensation for back injury comprises 56.4% of all indemnity costs and 55.1% of all medical costs.2 In one Australian state, nurse back injury claims accounted for $A2.39 million expenditure in one financial year.14

Surprisingly, few systematic reviews have investigated the efficacy of interventions to prevent back pain and injury in nurses. One review which included trials over a 10‐year period up to 1998 provided a narrative summary but failed to score the methodological quality of trials or interpret findings in consideration of varying design flaws.15 A systematic review of interventions to reduce musculoskeletal injuries associated with handling patients included many relevant trials but was not focused on nurses and accepted low‐quality designs such as professional opinion.16

The primary objective of this study was to systematically review the literature to determine whether there are interventions with proven efficacy that prevent back pain and back injury in nurses. A review focusing specifically on nurses was considered necessary due to the unique nature of nursing work.

Methods

The methodological design of this review followed guidelines developed by the Editorial Board of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group.17,18 The guidelines directed a five‐step process that involved a comprehensive literature search strategy, application of selection criteria to identify eligible trials, grading of methodological quality, extraction of data and synthesis of evidence. Unlike other reviews, we reviewed only prospective trials with concurrent control groups, scored the quality of trials, differentiated between high and low quality studies, and synthesised evidence on the basis of study quality. As there is frequent indiscriminate use of terminology, we chose to review all trials focussing on low back pain (LBP), back pain and back injury to comprehensively examine the efficacy of interventions that aim to prevent back trouble in nurses. In order to identify and minimise (where possible) any potential publication biases, searches were performed in a large number of databases with no language restriction.

Search strategy for identification of studies

Relevant studies were identified using a comprehensive search strategy that included:

A computer aided search of relevant databases including MEDLINE (1966–October 2004), EMBASE (1993–November 2004), CINAHL (1982–October 2004), Academic Search Elite (1985–October 2004), Health Source Nursing/Academic Edition (1975–October 2004), PEDro (1929–September 2004), PsycInfo (1840–October 2004), PsycArticles (1985–October 2004), Joanna Briggs Institute Systematic Review Database for Evidence Based Nursing and Midwifery (1998–September 2004) databases and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (1898–September 2004). Searches were undertaken without language or year restriction using medical subject headings, key words and free text words where necessary.

A search of PhD dissertations using the Australian Digital Thesis Program (1997–November 2004), Index to Theses (1970–November 2004) and Digital Dissertations (1861–November 2004) databases.

Screening reference lists of included papers for further eligible studies.

The search terms and strategies utilised in each of the databases are available from the corresponding author.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Studies

Due to the language skills of the reviewing team, controlled trials that were randomised (RCTs) or non‐randomised (NCTs) and published in English or German were included without year restriction. Both RCTs and NCTs were accepted in order to maximise the pool of available data. Studies needed to be of prospective design with comparison intervention and control groups recruited from the same setting.

Participants

All grades of nurses, nursing aides and nursing students were included without gender or age limitation. Studies that included nurses as well as non‐nursing participants were excluded if they did not analyse and report the nursing cohort separately. There was no restriction on history of back pain and back injury.

Interventions

Interventions aimed at the prevention of LBP, back pain and/or back injury were included. Both singular and multidimensional strategies were eligible. Laboratory testing of patient handling techniques or equipment was excluded.

Outcome measures

To be eligible, studies had to assess LBP and/or back pain and/or back injury outcomes. Secondary outcomes of interest included functional status (eg, disability, restricted work and leisure activities) and time loss from work.

Selection, quality assessment and analysis

Study selection

Three reviewers (AD, SM, SS) participated in study selection. For each database, two authors independently screened hits and applied selection criteria. SS translated German papers for independent assessment by the other two reviewers. Selection criteria had been piloted on a sample of abstracts using title, abstract and keywords. For those studies where eligibility was unclear from the title and abstract, the full text of the article was obtained and assessed. To avoid multiple publication bias, efforts were made to identify any multiple publications arising from single studies and pool data.

Methodological quality assessment

The methodological quality of studies was assessed by AD and SM. All grading was performed independently with any disagreements between authors resolved via a consensus meeting. Blinding reviewers to author and publication details was not possible as reviewers had been involved in screening databases and selecting studies. One of the reviewers was trained in an unrelated health discipline and was unfamiliar with the back pain literature.

The methodological quality of studies was evaluated using criteria recommended in relevant guidelines17,18 and adapted for the study designs included in the review. Criteria regarding blinding were omitted as in many interventions it was not possible to blind the subject or care giver to the treatment, and blinding the outcome assessor was irrelevant as outcomes were self‐reported. A criterion assessing compliance was omitted as in many cases no control treatment was applied, and compliance was rarely measured in the intervention group. Criteria were pilot tested on a related but ineligible paper. The “internal validity” and “descriptive quality” of trials were evaluated using six criteria and each given a score out of 6 (table 1). A total score out of 12 was assigned after combining these two values. Criteria were graded as “yes” (1), “no” (0) or “don't know” (0). A grade of “don't know” was assigned when data were unavailable (eg, weren't collected) and/or when information provided in the paper and by authors in personal correspondence was insufficient to score the criteria. For example, an author merely stating that randomisation was performed was inadequate to score a “yes” for criterion A. Rather, description of the specific method of randomisation utilised was required. Studies were graded according to quality assessment scores. Studies scoring a minimum of 4.5/6 for internal validity with a total score of 9/12 or greater were deemed “high quality” with all remaining studies graded as “low quality”.

Table 1 Methodological quality criteria.

| Score | ||

|---|---|---|

| Internal validity (IV) criteria | ||

| A | Method of randomisation adequate (eg, random number table)? | 1 |

| B | Treatment allocation concealed? | 1 |

| C | Groups similar at baseline regarding age, gender, history of back pain, area of work, pregnancy, nurse grade and baseline measures? | 1 |

| D | Co‐interventions avoided or similar? | 1 |

| E | i) Drop‐out/withdrawal individuals adequately described? | 0.5 |

| ii) Drop‐out rate acceptable (<20% for short‐term and <30% for long‐term follow‐up)? | 0.5 | |

| F | Intention to treat method of analysis (irrespective of compliance, change in group status)? | 1 |

| IV score | 6 | |

| Descriptive quality (DQ) criteria | ||

| G | Eligibility criteria specified? | 1 |

| H | Index and control interventions explicitly described? | 1 |

| I | i) Short‐term follow‐up measurement (⩽3 months post initiation of intervention)? | 0.5 |

| ii) Long‐term follow‐up measurement (>3 months post initiation of intervention)? | 0.5 | |

| J | Sample size for each group described at randomisation and all important outcome assessments? | 1 |

| K | Point estimates and measures of variability presented for primary and secondary outcome measures? | 1 |

| L | i) Sampling method adequate? | 0.5 |

| ii) Participation rate adequate (>80%)? | 0.5 | |

| DQ score | 6 | |

| Total score (IV+DQ scores) | 12 | |

When papers provided insufficient information to assess criteria, authors of included studies were contacted via email or post to request further information. When contact information was not given on included papers or was out of date, current contact details were identified by searching for more recent publications of the author in MEDLINE and searching on general internet search engines. Second authors were approached if the first author of the paper could not be contacted or did not reply. Where author responses were unclear, they were asked to provide further information and clarification.

Data extraction and analysis

Two reviewers (AD and SM) independently extracted data using a standardised and piloted form. Studies were grouped according to intervention method and then the strength of evidence was evaluated using a qualitative method of best‐evidence synthesis for data analysis. This method evaluates the number, methodological quality and outcomes of studies to provide an overall evidence rating for each intervention type (n = 5 levels). Quality of evidence was graded as follows:

Strong: consistent findings among multiple high quality RCTs

Moderate: one high quality RCT or consistent findings among multiple low quality RCTs/NCTs

Limited: one low quality RCT or NCT

Conflicting: inconsistent findings among multiple trials (RCTs/NCTs)

No evidence from any trials.

Two sensitivity analyses were undertaken to investigate how sensitive the results of the review were in relation to the way it was performed. The first sensitivity analysis investigated the impact of the selected cut‐off point for qualification as a high quality trial. In this analysis, the cut‐off point was amended to a minimum score of 3/6 for both internal validity and descriptive criteria. The second sensitivity analysis examined whether evidence findings changed when more potentially biased trials were omitted from analysis. Here, studies scoring less than 2/6 for internal validity were excluded from the synthesis of evidence.

Study selection

On the basis of title and/or abstract information, 51 papers were identified. Thirty one of these were deemed ineligible following review of the full paper. Reasons for exclusion included lack of a control group, inadequate control, lack of between‐group comparison, non‐nursing subjects, laboratory testing and failing to report back pain or injury symptoms separately or at all. One study was ineligible on the basis of publication language.19

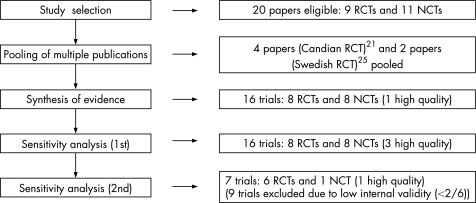

Twenty papers reporting nine RCTs and 11 NCTs met selection criteria. Studies with incomplete randomisation of participants were classified as NCTs.20 Multiple publications from individual trials occurred in two instances, with four papers21,22,23,24 reporting a Canadian NCT and two papers25,26 presenting data from a Swedish RCT. Data given in multiple publications were pooled and are referred to by the first paper published. After pooling, eight RCTs and eight NCTs were included. Figure 1 shows the number of trials at each stage of the review process.

Figure 1 Included trials at study selection, pooling, synthesis of evidence and sensitivity analyses.

Study quality

Quality appraisal results are presented in table 2. Further information to enable grading of quality was required for all trials, and all authors (first or second) were contactable and responded. In two instances, authors were not able to provide information, and in some cases authors did not answer all questions. Lack of necessary information resulted in criteria being assigned a grade of “don't know”. There was initial disagreement between reviewers on 56 (22%) of 255 scored items. This was due to reading or interpretation errors and was resolved via consensus meeting.

Table 2 Methodological quality assessment results.

| Trials | Internal validity (IV) criteria | Descriptive quality (DQ) criteria | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E(i) | E(ii) | F | IV score | G | H | I(i) | I(ii) | J | K | L(i) | L(ii)* | DQ score | Total score | ||||

| Alexandre et al37 | + | ? | ? | + | − | + | + | 3.5/6 | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | NA | 4.5/6 | 8.0/12 | |||

| Allen and Wilder34 | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | 4.5/6 | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | NA | 1.5/6 | 6.0/12 | |||

| Best38 | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | 4.0/6 | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | 4.0/6 | 8.0/12 | |||

| Dehlin et al28 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0/6 | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | NA | 2.5/6 | 2.5/12 | |||

| Dehlin et al29 | − | − | ? | − | − | − | − | 0/6 | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | NA | 3.5/6 | 3.5/12 | |||

| Gundewall et al30 | + | + | ? | − | − | + | − | 2.5/6 | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | ? | 4.0/6 | 6.5/12 | |||

| Hellsing et al32 | − | − | ? | ? | − | ? | ? | 0/6 | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | ? | 3.0/6 | 3.0/12 | |||

| Horneij et al27 | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | 4.5/6 | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | 5.5/6 | 10.0/12 | |||

| Knibbe and Friele20 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | 1.5/6 | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | 2.5/6 | 4.0/12 | |||

| Linton et al33 | + | + | ? | − | − | + | − | 2.5/6 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | NA | 3.0/6 | 5.5/12 | |||

| Smedley et al31 | − | − | ? | − | − | − | − | 0/6 | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | 4.0/6 | 4.0/12 | |||

| Videman et al11 | − | − | + | ? | − | − | + | 2.0/6 | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | 3.5/6 | 5.5/12 | |||

| Wigaeus Hjelm et al25 | ? | ? | ? | + | − | + | − | 1.5/6 | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | ? | 3.0/6 | 4.5/12 | |||

| Wood35 | − | − | ? | − | − | ? | − | 0/6 | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | 3.5/6 | 3.5/12 | |||

| Yassi et al21 | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | 1.5/6 | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | 4.0/6 | 5.5/12 | |||

| Yassi et al36 | ? | ? | ? | ? | − | + | + | 1.5/6 | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | 4.5/6 | 6.0/12 | |||

+, yes; −, no; ?, don't know.

*If score “no” for L(i), then L(ii) is NA.

Mean internal validity scores were 3.1/6 (range 1.5–4.5) for RCTs and 0.6/6 (range 0–2.0) for NCTs. Mean descriptive quality scores were 3.9/6 (range 1.5–5.5) for RCTs and 3.3/6 (range 2.5–4.0) for NCTs. Of 16 trials included, only one RCT qualified as high quality according to our criteria.27

Study characteristics

Included studies are presented in tables 3–5 according to intervention and listed under subcategories in a hierarchical order by internal validity score. Nurses, nursing aides, student nurses and at times a combination of nurse categories comprised study cohorts. In relation to outcomes, eight trials reported LBP,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 one reported back pain,20 two reported back injury34,35 and five reported a combination of outcomes.11,21,36,37,38

Table 3 Trials of exercise interventions.

| Study (IV score) | Methods | Subjects | Intervention | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise at work | |||||

| Gundewall | RCT: stratified then | 69 nurses/nursing | (1) 20‐min strength, endurance, | LBP intensity, number | Reduction of LBP |

| et al30 | random allocation | aides with and | coordination exercise (6 sessions/ | of days with LBP, lost | prevalence (p<0.02), LBP |

| (2.5/6) | to 2 groups. Follow‐ | without LBP work‐ | month for 13 months); (2) no | work days due to LBP | intensity (p<0.04) and lost |

| up 13 months | ing in hospital | intervention | work days (p<0.01) | ||

| Wigaeus | RCT: random | 131 nursing | All sessions 40 min, 2×/week for | LBP intensity | Unclear: Josephson et al26 |

| Hjelm | allocation to 3 | aides working | 6 months: (1) bicycle ergometer; | report no significant | |

| et al,25 | groups. Follow‐ | in hospital | (2) 3×15 repetitions on 7 | differences; Wigaeus Hjelm | |

| Josephson | up 6 months | equipments; (3) education in | et al25 report reduced LBP in (1) | ||

| et al26 | occupational health and stress | and (2) vs (3) in those with | |||

| (1.5/6) | management | LBP at baseline | |||

| Dehlin | NCT: allocation by | 46 female nursing | 2×/week for 8 weeks: | Frequency, intensity, | Reduction in LBP duration |

| et al28 | work building to 3 | aides with | (1) strengthening exercise; (2) 30‐ | duration of LBP and | in (1) vs (2). No other |

| (0/6) | groups. Follow‐up | LBP working | min lectures on medicine and | influence of LBP on | significant differences |

| 8 weeks | in hospital | nursing care; (3) no intervention | working capacity | ||

| Dehlin | NCT: allocation by | 45 female nursing | 2×/week for 8 weeks: (1) 45‐min | Frequency, intensity, | No significant differences |

| et al29 | work building to 3 | aides with LBP | endurance and aerobic exercise; | duration of LBP and | |

| (0/6) | groups. Follow‐up | working in | (2) manual handling training; | influence of LBP on | |

| 8 weeks | hospital | (3) no intervention | working capacity | ||

| Exercise at home | |||||

| Horneij | RCT: random | 282 female | (1) Posture, balance, endurance, | LBP prevalence, | No significant differences in |

| et al27 | allocation to 3 | nursing aides | functional, stretching and | interference with | LBP, but (1) had less activity |

| (4.5/6) | groups. Follow‐up | working in home‐ | cardiovascular exercises | activities, pain | interference compared with (3) |

| 12 and 18 months | care services | (suggested ⩾2×/week); (2) stress | drawing | at 12‐month follow‐up | |

| reduction training 7×1.5 h | |||||

| plus follow‐up; (3) “live as usual” | |||||

IV, internal validity.

Table 4 Trials of manual handling interventions.

| Study (IV score) | Methods | Subjects | Intervention | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equipment provision and training | |||||

| Yassi | RCT: random allocation | 346 nurses/nursing | (1) Sliding and transfer equipment, | Work‐related LBP, | Compared with (3), LBP |

| et al36 | to 3 groups. Follow‐up | aides working in | one lifter, 3‐h MH training; | disability, back | reduced in (2) at 6 months |

| (1.5/6) | 6 and 12 months | hospital | (2) multiple new lifters, sit‐stand | injuries | (p = 0.02) and in (1) at |

| lifters and sliding devices, 3‐h | 12 months (p = 0.04). No | ||||

| MH training; (3) usual practice | change in injury or disability | ||||

| Knibbe | NCT: incomplete random | 355 female nurses | (1) 40 hoists, 12 lifting | Back pain | No significant differences |

| and | allocation of 20 teams to | working in home | coordinators, 4‐h MH training; | prevalence | |

| Friele20 | 2 groups. Follow‐up | care services | (2) usual practice (2 hoists) | ||

| (1.5/6) | 12 months | ||||

| Smedley | NCT: allocation by | Female nurses | (1) 700 sliding sheets, additional | Prevalence of LBP | No significant differences |

| et al31 | hospital to 2 groups. | working in hospital: | MH equipment and training; | lasting more than | |

| (0/6) | Follow‐up 32 months | 1157 at baseline | (2) no study intervention, but | a day during the | |

| and 1078 at follow‐ | hospital improved MH training | past month | |||

| up | and equipment during study | ||||

| Training in the workplace | |||||

| Best38 | RCT: random allocation | 55 female nurses | (1) 32‐h MH training; (2) and | Back pain frequency | No significant differences |

| (4/6) | by nursing home to | working in nursing | (3): in‐house orientation | and severity, back | |

| 3 groups. Follow‐up | homes | training only | injury | ||

| 3 and 12 months | |||||

| Dehlin | NCT: allocation by | 45 female nursing | 2×/week for 8 weeks: (1) 45‐min | Frequency, intensity, | No significant differences |

| et al29 | work building to 3 | aides with LBP | endurance and aerobic exercise; | duration of LBP and | |

| (0/6) | groups. Follow‐up | working in hospital | (2) MH training; | influence of LBP on | |

| 8 weeks | (3) no intervention | working capacity | |||

| Wood35 | NCT: allocation by | 42 registered nurses | (1) 30‐min task observation and | Back injury | No significant differences |

| (0/6) | hospital unit to 2 groups. | and 135 nursing aides | feedback, 1‐h MH training; | ||

| Follow‐up 12 months | working in hospital | (2) no intervention | |||

| Training during nursing studies | |||||

| Videman | NCT: allocation by year | 308 student nurses | (1) 40‐h training in biomechanics | Back pain incidence, | No significant differences |

| et al11 | of enrolment to 2 groups. | and ergonomics over 2.5 years; | severity, injury and | ||

| (2/6) | Follow‐up 12 months | (2) usual curriculum | disability | ||

| Hellsing | NCT: allocation by | 52 student nurses | (1) 2 h/week ergonomics | Annual LBP | No significant differences |

| et al32 | school to 2 groups. | education over 2 years; | |||

| (0/6) | Follow‐up 12, 24 | (2) usual curriculum (5 h | |||

| and 36 months | ergonomics education) | ||||

IV, internal validity; MH, manual handling.

Table 5 Trials of lumbar supports, stress management and multidimensional interventions.

| Study (IV score) | Methods | Subjects | Intervention | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumbar supports | |||||

| Allen and | RCT: random | 50 licensed practical | (1) Training in back belts, | Incident back | Reduced incidence of back |

| Wilder34 | allocation to | nurses working in | wearing belts when lifting, | injuries and | injuries, no analysis of lost |

| (4.5/6) | 2 groups. Follow‐ | hospital | 3‐h MH training; (2) 3‐h | total hours lost | work hours reported |

| up 6 months | MH training only | due to injury | |||

| Stress management | |||||

| Horneij | RCT: random | 282 female nursing | (1) Home exercise program; | LBP prevalence, | No significant differences for |

| et al27 | allocation to 3 | aides working in home | (2) stress reduction training | interference with | stress management program |

| (4.5/6) | groups. Follow‐up | care services | of 7×1.5 h plus 3‐ and 6‐month | activities, pain | |

| 12 and 18 months | follow‐up; (3) “live as usual” | drawing | |||

| Multidimensional interventions | |||||

| Alexandre | RCT: random | 56 female nursing aides | (1) Strength and flexibility | LBP frequency | Reduced LBP frequency (7‐ |

| et al37 | allocation to 2 | with back pain working | exercise, relaxation and MH | and intensity | day) (p = 0.07) and intensity |

| (3.5/6) | groups. Follow‐ | in hospital | education (1 h, 2×/week for | (7‐day and | (7‐day and 2‐month) |

| up 4 months | 4 months); (2) 45‐min lecture | 2‐month) | |||

| on anatomy and MH | |||||

| Linton | RCT: random | 66 female licensed practical | (1) 5×40 h/week residential | Daily LBP intensity, | Reduced LBP intensity |

| et al33 | allocation to 2 | nurses/nursing aides working | program (4 h exercise/day, | satisfaction with | (p = 0.01), greater satisfaction |

| (2.5/6) | groups. Follow‐up | in hospital who had taken | MH training, pain and lifestyle | ADL, days lost | with ADL post‐intervention |

| post‐intervention | sick leave for back pain in | management and risk | due to sick leave | (p<0.01), no significant | |

| and 6 months | previous 2 years | assessment); (2) waiting list | change in sick leave | ||

| Yassi | NCT: allocation to | 183 registered nurses | (1) Post injury program: physician, | LBP, disability, | Reduced LBP, disability, |

| et al21 | 2 groups based | working in hospital who | physiotherapy, occupational | back injuries and | back injuries, lost‐time back |

| (1.5/6) | on ward. Follow‐ | sustained an acute back | therapy if >4 days off work, | lost work time | injuries and total work time |

| up 6 months | injury during the study | modified duties; (2) routine care | lost (p<0.01) | ||

ADL, activities of daily living; IV, internal validity; MH, manual handling.

Analysis of intervention efficacy

Exercise

We identified three RCTs and two NCTs of exercise interventions that aimed to prevent LBP in nurses (table 3). Three trials reported no effect,27,28,29 including a high quality trial of an individually designed home exercise program.27 One trial of a 13‐month physiotherapist‐led exercise program undertaken in the workplace reported a significant reduction in LBP prevalence and intensity.30 In the study by Wigaeus Hjelm and colleagues25 the results were unclear: different findings (positive and negative) are reported in two papers describing the study (table 3). Considered together, there is conflicting evidence for the efficacy of exercise interventions.

Manual handling interventions

Eight trials of manual handling interventions applied as a singular strategy were identified: two RCTs and six NCTs (table 4). The interventions included manual handling training at the workplace29,35,38 and during nursing studies,11,32 and the provision of manual handling equipment and training.20,31,36 All trials showed no effect with the exception of the RCT by Yassi et al36 which showed a reduction in LBP in both intervention groups, although no change in injury or disability. When the levels of evidence ratings are applied, there is conflicting evidence for provision of manual handling equipment and training, and moderate evidence that manual handling training alone (in the workplace or during nurse training) is not effective in preventing back pain.

Lumbar supports

A single trial was identified that tested the efficacy of lumbar supports. Allen and Wilder's34 RCT of back belt utilisation during patient transfers showed a positive effect with less back injury in study nurses (table 5). This provides limited evidence that lumbar supports are effective in preventing back injury in nurses.

Stress management

The stress management intervention tested by Horneij and colleagues27 in a high quality trial did not reduce LBP (table 5). Therefore, there is moderate evidence that stress management interventions are not effective in preventing LBP in nurses.

Multidimensional interventions

Three trials applied combined or multidimensional intervention approaches (table 5). Alexandre et al37 examined a combined manual handling and exercise intervention and found a reduction in LBP frequency and intensity. Linton and colleagues33 applied an intensive residential program of exercise, manual handling training, pain and lifestyle management and risk assessment training that resulted in a reduction in LBP intensity. Yassi et al21 implemented an early intervention post injury program that involved management by a physician, physiotherapist and occupational therapist and modified duties on return to work. It showed a positive effect on LBP and back injury. The evidence from these singular trials provides limited evidence that each multidimensional intervention strategy is effective. Considered together, there is moderate evidence that multidimensional interventions are effective in preventing LBP in nurses.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes such as functional status and sick leave were less frequently measured. There were no cases of multiple trials for any similar intervention and outcome. Gundewall and colleagues'30 physiotherapist‐led exercise program provided limited evidence for a reduction in time loss from work. The home exercise program of Horneij et al27 provided moderate evidence for a reduction in LBP interference with work and/or leisure activities, whilst the stress management program tested in the same study was ineffective in this regard. The combined exercise and behavioural therapy intervention of Linton and colleagues33 provided limited evidence for an increase in satisfaction with activities of daily living. Finally, the early intervention program by Yassi et al21 provided limited evidence for reduction in disability and time loss from work.

Sensitivity analyses

Figure 1 shows the number of trials included during the sensitivity analyses. During the first sensitivity analysis, the cut‐off for high quality status was reduced (see Methods), resulting in two further trials being classified as high quality. These include the multidimensional manual handling and exercise intervention of Alexandre et al37 and the manual handling training intervention by Best.38 There were no changes to overall evidence findings as a result of these changes. In the second sensitivity analysis, nine trials were excluded due to scoring less than 2/6 on internal validity criteria20,21,25,28,29,31,32,35,36 leaving seven eligible trials. There was one change to the evidence grading. We found moderate evidence that the provision of manual handling equipment and education is not effective (compared with conflicting evidence previously). The minor changes in evidence findings during the sensitivity analyses indicate the results of this review are robust and not greatly affected by alterations in review methodology.

Discussion

This review was needed to synthesise current evidence in relation to back pain and injury prevention in nurses. A lack of high quality studies and infrequent trial replication resulted in no strong evidence for or against any intervention method. Whilst no definitive statements can be made, moderate evidence from multiple trials suggests that multidimensional strategies are effective and manual handling training in isolation is ineffective. For all other interventions there is conflicting evidence or only single trials are available. The specific findings of the review merit discussion in relation to current policy and evidence from other populations.

Intervention efficacy

Our review concluded that there is moderate evidence that manual handling training alone does not prevent back pain in nurses. This finding is consistent with a review which includes data from multiple worker populations.39 Hignett16 found strong evidence that manual handling interventions based predominantly on technique training do not reduce musculoskeletal injury rates. Many nursing workplaces provide annual manual handling training to minimise LBP and prevent workplace back injury. The evidence from this review and that performed by others16,39 indicates that workplace policies that involve this strategy in isolation are not supported by evidence and should be reconsidered.

Back pain is complex and multifaceted, and the application of multidimensional interventions has been recommended by others.15 We found consistent positive findings to support the efficacy of multidimensional strategies in preventing LBP in nurses.21,33,37 Although interventions varied greatly in design and content, when considered together there was moderate evidence supporting multidimensional programs. A synthesis of systematic review evidence by Burton and colleagues39 supported the efficacy of multidimensional interventions for preventing LBP in worker populations, although it was not suggested what the content of these interventions should be and effect size was thought to be potentially modest.

Based on the literature assessed in this study, there is conflicting evidence for interventions that involve the provision of manual handling equipment and education. The RCT by Yassi et al36 included a “no strenuous lifting” group (group 1) and a “safe lifting” group (group 2) and found a reduction in LBP in both groups. The other trials showed no effect,20,31 although notably the trial by Smedley and colleagues31 had marked methodological flaws.

In the last decade, nursing associations have developed and advocated “no lift” policies, where equipment is provided and manual lifting is eliminated except in exceptional circumstances.40 A recent evaluation of a “no lift” program in Australian hospitals reported “strong evidence” that it reduced back injury, pain symptoms and sick leave in nursing staff.40 This claim is questionable, since the evaluation was cross‐sectional and differences between groups such as full‐time work and years in the profession (an independent risk factor for back pain)5 could have influenced findings. An evaluation of a multifaceted ergonomics program that included a “no lift” policy in the United States also reported positive findings41 but was evaluated using a non‐controlled pre‐post design that is inherently susceptible to bias. Of the three trials included in this review, the “no strenuous lifting” intervention of Yassi and colleagues36 was most closely aligned to the “no lift” strategy and reported a positive effect in relation to LBP although no change in injury or disability outcomes. The other trials provided equipment and education but did not specifically stipulate that manual lifting should be eliminated.20,31 Hence the popular “no lift” policy may have some efficacy in nursing populations, but there is no consistent evidence presently available to support its widespread application.

We found conflicting evidence for the efficacy of exercise to prevent LBP in nurses. Two trials were highly susceptible to bias, with scores of 0/6 for internal validity.28,29 The results for one RCT were unclear with conflicting findings reported in two papers describing the same study.25,42 In the sensitivity analysis, lowest quality evidence was omitted leading to consideration of two trials: an individualised home exercise program did not reduce LBP prevalence,27 and physiotherapist‐led exercise in the workplace resulted in reduced LBP prevalence and intensity.30 The findings suggest that self‐paced exercise programs performed in nurses' leisure time may not be as effective as directed and physiotherapist‐led programs undertaken in the workplace. The ineffectiveness of the exercise program of Horneij and colleagues27 could possibly be due to poor compliance, since the exercise group did not perform home exercises more frequently than comparison groups. The conflicting findings in the two studies could also be related to differences in the frequency and type of exercises performed.

European guidelines report high level evidence to recommend physical exercise as an intervention for prevention of LBP in general worker populations.39 Other systematic reviews report limited43,44 and strong45,46 evidence to support the use of exercise interventions in preventing LBP, with a meta‐analysis indicating a moderate effect size (0.53).43 The type of exercise that is most effective is not known. One review recommended strengthening and stretching exercises over other strategies,47 and the successful interventions in another review commonly utilised strengthening and trunk stabilising exercises.46 Programs of specific stabilisation exercises involving deep spinal and abominal muscles have recently been shown to be more effective than usual medical care and education in treating chronic LBP, and as effective as spinal manipulative therapy.48

One high quality trial in this review tested the efficacy of a stress management program and provided moderate evidence that this intervention in isolation is ineffective in preventing LBP in nurses.27 It could be argued that stress is not an important risk factor for back pain, as there is inconsistent evidence for an association between job stress and back disorders in nursing cohorts.5 Systematic reviews of the role of occupational stress in back pain in general populations are also inconsistent: Linton49 found strong evidence that stress is related to future back pain, but Hartvigsen et al50 disputed this conclusion based on their finding of insufficient evidence. A lack of trial replication inhibits the conclusions that can be drawn regarding the effectiveness of stress management in preventing back pain and injury in nurses.

We found limited evidence from a single trial to support the use of lumbar supports to prevent back injury in nurses. This is in contrast to other reviews that found lumbar supports are ineffective in preventing occupational LBP43,45,51 or found inconsistent results.52 European guidelines state that back belts/lumbar supports are not recommended for prevention of LBP in workers.39 Whether nurses are unique in their response to lumbar support during patient handling tasks is unknown due to a lack of multiple trials.

Limitations

There are a number of potential limitations in this review that warrant consideration. Firstly, whilst the literature search was comprehensive and included 10 relevant databases, theses and manual searching of reference lists, the slim possibility that published trials were missed should be acknowledged. Publication bias relating to publishing positive findings may also have played a role. Bias due to publication language was potentially present with one trial ineligible due to reporting in Finnish.19 It is not known whether the trial, which appeared relevant based on abstract information available in the English language, would have met selection criteria following review of the full paper. Notably, the trial evaluated the efficacy of an exercise intervention, and since this review found conflicting evidence in relation to exercise, additional data from the Finnish study (or the lack thereof) are unlikely to have influenced the conclusions of this review.

Further possible bias in systematic reviews relates to the provision of adequate information by authors of papers to enable grading of methodological quality. In some cases authors of trials included in this review were not able to provide information to the review team (such as when data were no longer accessible). In other cases authors did not respond to requests for information. This may have impacted upon methodological quality scores and the review findings.

It was not possible to present quantitative data on the magnitude of effect of examined interventions in this review. Meta‐analyses of trials in each intervention subgroup were considered inappropriate by the reviewing team due to the methodological heterogeneity and poor quality of included studies. Data pooling from low quality studies could compound any biases present in individual studies and result in an erroneous and misleading pooled estimate. In any case, meta‐analyses could not be performed as only three of 16 included studies reported data necessary to calculate effect sizes.

Finally, whilst the database search terms and criteria used to assess methodological quality were based on those recommended by the editorial board of a leading back review group,17,18 and have been used in other systematic reviews,53,54 the possibility remains that bias was introduced by the criteria selected for this analysis.

Implications for research

The overall poor quality of trials undertaken on interventions to prevent back pain and injury in nursing cohorts is concerning given that this is a high risk population with frequent and expensive work absenteeism and workers' compensation.2,13,14 Although many intervention studies are reported in the literature, a large number of trials were ineligible for this review due to inadequacies of the control group. Further, most eligible trials scored poorly on internal validity criteria, indicating a high susceptibility to bias.

Health economic evaluation of preventative programs has infrequently been undertaken, with the exception of two trials: Yassi et al21 found that combined medical and compensation expenditure was significantly reduced in back‐injured nurses who underwent a multidisciplinary therapy program, and Gundewall et al30 found a cost‐benefit ratio greater than 10 in their trial of physiotherapist‐led exercise. Cost‐benefit analyses that contrast intervention expenses with workplace efficiency gains and savings from reduced workers' compensation and work absenteeism are important to inform decisions relating to policy.

Adequately powered high quality randomised controlled studies are needed to answer important research questions about the efficacy of interventions to prevent back pain and back injury in nurses. Internal validity must be maximised, outcome instruments must have proven reliability and validity, and reporting must be comprehensive. Outcome measures should be consistent and include a range of measures such as back pain frequency and severity, injury, functional status, time loss from work and cost‐benefit ratio.

Multidimensional interventions show consistent efficacy and warrant further investigation. The most appropriate components are not known, and different composite interventions should be tested with comparison groups. Manual handling training as a singular strategy has not been effective and appears unworthy of further examination. There is conflicting evidence for the efficacy of exercise. Consistent positive findings in other populations suggest that it is a strategy worthy of further study, and examination of different forms of exercise are needed to identify which, if any, are effective in nurses. Due to conflicting evidence, further research is needed to determine whether manual handling interventions that incorporate equipment and training, such as “no lift” strategies, are effective. Only single trials have been undertaken on the effectiveness of stress management and lumbar supports in nursing cohorts, resulting in limited data available to evaluate their efficacy. Systematic review evidence from other working populations might be used to guide research planning decisions for these intervention methods. Other intervention strategies not previously investigated with nurses might also be considered.

Since nurse qualifications, work settings and job tasks can vary considerably, trials should be replicated with different grades of nurses and in different work environments to investigate consistency of results. Nurses with pre‐existing back pain and injury and those with no history of symptoms should be included in the participant cohort to investigate primary and secondary preventative effects.

Conclusion

It is clear from this review that there is a paucity of quality evidence for interventions that aim to prevent back pain and back injury in nurses. This is disappointing, since work absenteeism and workers' compensation due to back disorders in nursing cohorts are both common and expensive. It is critical that policy makers become aware of the current evidence in relation to preventative interventions: data from multiple trials suggest that multidimensional strategies are effective and manual handling training in isolation is ineffective; however, there is no strong evidence to support any firm conclusions. For all other interventions (exercise, lumbar supports, stress management and manual handling equipment and training) there is conflicting evidence or only single trials have been undertaken. Low quality studies do little to answer research questions and should not be endorsed. This review highlights the need for adequately powered randomised controlled studies to provide high quality evidence regarding the effectiveness of interventions to prevent back pain and injury in nursing populations.

Main messages

A systematic literature review identified 16 predominantly low quality trials of interventions that aim to prevent back pain or back injury in nursing cohorts.

There is moderate evidence from multiple trials that manual handling training in isolation is not effective and multidimensional strategies are effective.

There is conflicting evidence regarding the efficacy of exercise and the provision of manual handling equipment and training as preventative measures.

Single trials provide limited evidence that lumbar supports are effective and moderate evidence that stress management programs are not effective.

High quality research is urgently needed to investigate conflicting findings and further examine the efficacy of interventions in preventing back pain and back injury in nurses.

Policy implications

Health service organisations must become aware of the evidence in relation to back pain and injury prevention in nurses and design policy accordingly.

Evidence from multiple trials suggests that manual handling training in isolation is not effective in preventing back pain and injury in nurses.

Multidimensional strategies show consistent positive outcomes although the most important intervention components are not known.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge WorkCover Corporation of South Australia for partial funding of this review. We thank the authors of studies included in this review for providing information to enable grading of methodological quality.

Abbreviations

LBP - low back pain

NCT - non‐randomised controlled trial

RCT - randomised controlled trial

Footnotes

Funding: WorkCover Corporation of South Australia provided financial support towards the completion of this systematic review. Professor Paul Hodges is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. The funding bodies had no role in designing or undertaking the review.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Hofmann F, Stossel U, Michaelis M.et al Low back pain and lumbago‐sciatica in nurses and a reference group of clerks: results of a comparative prevalence study in Germany. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 200275484–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen‐Mansfield J, Culpepper W J, Carter P. Nursing staff back injuries: prevalence and costs in long term care facilities. AAOHN J 1996449–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heliovaara M. Occupation and risk of herniated lumbar intervertebral disc or sciatica leading to hospitalization. J Chronic Dis 198740259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bureau of Labor Statistics Workplace injuries and illnesses in 2005. Washington, DC: United States Department of Labor, 2006, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/osh.pdf (accessed 25 June 2007)

- 5.Sherehiy B, Karwowski W, Marek T. Relationship between risk factors and musculoskeletal disorders in the nursing profession: a systematic review. Occupational Ergonomics 20044241–279. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldasseroni A, Tartaglia R, Sgarrella C.et al Frequenza della lombalgia in una coorte di allievi infermieri. Med Lav 199889242–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ready A E, Boreskie S L, Law S A.et al Fitness and lifestyle parameters fail to predict back injuries in nurses. Can J Appl Physiol 19931880–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feyer A, Herbison P, Williamson A M.et al The role of physical and psychological factors in occupational low back pain: a prospective cohort study. Occup Environ Med 200057116–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mostardi R, Noe D, Kovacik M.et al Isokinetic lifting strength and occupational injury. A prospective study. Spine 199217189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klaber Moffett J A, Hughes G I, Griffiths P. A longitudinal study of low back pain in student nurses. Int J Nurs Stud 199330197–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Videman T, Rauhala H, Asp S.et al Patient‐handling skill, back injuries and back pain. An intervention study in nursing. Spine 198914148–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams M, Mannion A, Dolan P. Personal risk factors for first‐time low back pain. Spine 1999242497–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bureau of Labor Statistics Case and demographic characteristics for work‐related injuries and illnesses involving days away from work. Resource table 10: detailed occupation by selected parts of body affected. United States Department of Labor, 2002. http://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/case/ostbl277.pdf (accessed 27 June 2007)

- 14.WorkCover Corporation of South Australia Nurses' back injury claims 1999–2002. Adelaide, South Australia: WorkCover Corporation of South Australia, 2004

- 15.Lagerstrom M, Hansson T, Hagberg M. Work‐related low‐back problems in nursing. Scand J Work Environ Health 199824449–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hignett S. Intervention strategies to reduce musculoskeletal injuries associated with handling patients: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med 200360e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Tulder M, Assendelft W J J, Koes B.et al Method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group for Spinal Disorders. Spine 1997222323–2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C.et al Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine 2003281290–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karvonen M J, Jarvinen T, Nummi J. Seurantatutkimus sairaanhoitajien selkavaivoista follow‐up study on the back problems of nurses. Helsinki, Finland: Institute of Occupational Health, 1977

- 20.Knibbe J J, Friele R D. The use of logs to assess exposure to manual handling of patients, illustrated in an intervention study in home care nursing. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 199924445–454. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yassi A, Tate R, Cooper J E.et al Early intervention for back‐injured nurses at a large Canadian tertiary care hospital: an evaluation of the effectiveness and cost benefits of a two‐year pilot project. Occup Med 199545209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper J E, Tate R B, Yassi A.et al Effect of an early intervention program on the relationship between subjective pain and disability measures in nurses with low back injury. Spine 1996212329–2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper J E, Tate R B, Yassi A. Components of initial and residual disability after back injury in nurses. Spine 1998232118–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tate R B, Yassi A, Cooper J. Predictors of time loss after back injury in nurses. Spine 1999241930–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wigaeus Hjelm E, Hagberg M, Hellstrom S. Prevention of musculoskeletal disorders in nursing aides by physical training. In: Hagberg M, Hofmann F, Stossel U, et al eds. Occupational health for health care workers. Freiburg, Germany: Ecomed, 1992364–366.

- 26.Josephson M, Hagberg M, Hjelm E W. Self‐reported physical exertion in geriatric care. A risk indicator for low back symptoms? Spine 1996212781–2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horneij E, Hemborg B, Jensen I.et al No significant differences between intervention programmes on neck, shoulder and low back pain: a prospective randomized study among home‐care personnel. J Rehabil Med 200133170–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dehlin O, Berg S, Hedenrud B.et al Muscle training, psychological perception of work and low‐back symptoms in nursing aides. Scand J Rehabil Med 197810201–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dehlin O, Berg S, Andersson G B.et al Effect of physical training and ergonomic counseling on the psychological perception of work and on the subjective assessment of low‐back insufficiency. Scand J Rehabil Med 1981131–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gundewall B, Liljeqvist M, Hansson T. Primary prevention of back symptoms and absence from work. A prospective randomized study among hospital employees. Spine 199318587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smedley J, Trevelyan F, Inskip H.et al Impact of ergonomic intervention on back pain among nurses. Scand J Work Environ Health 200329117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hellsing A L, Linton S J, Andershed B.et al Ergonomic education for nursing students. Int J Nurs Stud 199330499–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linton S, Bradley L A, Jensen I.et al The secondary prevention of low back pain: a controlled study with follow‐up. Pain 198936197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allen S, Wilder K. Back belts pay off for nurses. Occup Health Saf 19966559–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wood D. Design and evaluation of a back injury prevention program within a geriatric hospital. Spine 19871277–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yassi A, Cooper J E, Tate R B.et al A randomized controlled trial to prevent patient lift and transfer injuries of health care workers. Spine 2001261739–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexandre N, de Moraes M, Correa Filho H.et al Evaluation of a program to reduce back pain in nursing personnel. Rev Saude Publica 200135356–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Best M. An evaluation of manutention training in preventing back strain and resultant injuries in nurses. Saf Sci 199725207–222. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burton A, Balague F, Cardon G.et al How to prevent low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 200519541–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Engkvist I. Evaluation of an intervention comprising a no lifting policy in Australian hospitals. Appl Ergon 200637141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nelson A, Matz M, Chen F.et al Development and evaluation of a multifaceted ergonomics program to prevent injuries associated with patient handling tasks. Int J Nurs Stud 200643717–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Josephson M, Lagerstrom M, Hagberg M.et al Musculoskeletal symptoms and job strain among nursing personnel: a study over a three year period. Occup Environ Med 199754681–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Poppel M, Hooftman W, Koes B. An update of a systematic review of controlled clinical trials on the primary prevention of back pain at the workplace. Occup Med (Lond) 200454345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maher C. A systematic review of workplace interventions to prevent low back pain. Aust J Physiother 200046259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Linton S, van Tulder M. Preventive interventions for back and neck pain problems: what is the evidence? Spine 200126778–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayden J, van Tulder M, Malmivaara A.et al Exercise therapy for treatment of non‐specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005(3)CD000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Hayden J, van Tulder M, Tomlinson G. Systematic review: strategies for using exercise therapy to improve outcomes in chronic low back pain. Ann Intern Med 2005142776–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferreira P, Ferreira M, Maher C.et al Specific stabilisation exercise for spinal and pelvic pain: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother 20065279–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Linton S. Occupational psychological factors increase the risk for back pain; a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil 20011153–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hartvigsen J, Lings S, Leboeuf‐Yde C.et al Psychosocial factors at work in relation to low back pain and consequences of low back pain: a systematic, critical review of prospective cohort studies. Occup Environ Med 200461e2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Tulder M, Jellema P, van Poppel M.et al Lumbar supports for prevention and treatment of low‐back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000(3)CD001823. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Ammendolia C, Kerr M, Bombardier C. Back belt use for prevention of occupational low back pain: a systematic review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 200528128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heymans M, van Tulder M, Esmail R.et al Back schools for non‐specific low‐back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004(4)CD000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Ostelo R, van Tulder M, Vlaeyen J.et al Behavioural treatment for chronic low‐back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005(1)CD002014. [DOI] [PubMed]