Abstract

Rumination is a serious problem demonstrated by some people with developmental disabilities, but previous research has not included a functional analysis and has rarely compared intervention methods during the assessment process. We conducted functional analyses with 2 children who displayed postmeal rumination and subsequently evaluated a supplemental feeding intervention following meals. Results showed that noncontingent food or liquid presentation effectively reduced rumination with both children.

Keywords: rumination, functional analysis, antecedent intervention, developmental disabilities

Rumination is the repetitive regurgitation, chewing, and reswallowing of previously ingested food, resulting in malnutrition, decreased resistance to disease, dehydration, esophagitis, and tooth decay (Rast, Johnston, Drum, & Conrin, 1981). Rumination sometimes occurs reflexively due to a medical condition (e.g., gastrointestinal distress), but frequently it is under the control of operant mechanisms. In particular, rumination may be automatically reinforced by the sensory consequences from reingesting food or stimulation to the mouth and throat. Accordingly, recent research has addressed an automatic reinforcement hypothesis by manipulating food quantity, composition, and presentation during and following meals (Dudley, Johnson, & Barnes, 2002; Heering, Wilder, & Ladd, 2003). However, previous research on rumination has not included a preintervention functional analysis and has infrequently compared different intervention methods. The purpose of the present study was to conduct functional analyses with 2 children who exhibited postmeal rumination; subsequently, we evaluated assessment-derived interventions.

Method

Participants and Setting

Participants were 2 children who attended a residential school for students with developmental disabilities. Alex was a 14-year-old boy who did not speak and had been diagnosed with global developmental delay. Tom was an 11-year-old boy, also nonverbal, who had a diagnosis of autism and mental retardation. Both participants had a lengthy history of rumination that occurred intermittently during the day but was most frequent 30 to 60 min after meals.

Measurement

Functional analyses (20 min) and intervention evaluations (15 to 20 min) were conducted individually with Alex and Tom in a room containing a table, two or three chairs, and session-specific materials. One session was scheduled each weekday 10 min after lunch. A therapist was present during all sessions. Rumination (upward movement of the throat, puffing of cheeks, swishing tongue, gurgling sounds) was measured by an in-room observer using 10-s partial-interval recording. During food and liquid conditions (described below), appropriate consumption could be differentiated from rumination by a chewing motion and clearly visible swallowing.

Interobserver agreement was assessed by having a second person record rumination simultaneously with the primary observer during 63% of functional analyses and 38% of intervention evaluations with Alex, and 40% of functional analyses and 33% of intervention evaluations with Tom. Interobserver agreement (interval-by-interval agreements divided by agreements plus disagreements and multiplied by 100%) averaged 91% (range, 74% to 100%) for functional analyses and 89% (range, 67% to 100%) for intervention evaluations with Alex. For Tom, agreement averaged 95% (range, 88% to 100%) for functional analyses and 97% (range, 95% to 100%) for intervention evaluations.

Procedure and Experimental Design

Functional Analysis

The functional analysis consisted of four conditions (attention, escape, play, no interaction) implemented in a multielement design (Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, & Richman, 1982/1994). Each condition was presented in a 5-min segment ordered randomly per session. In the attention condition, the therapist read a magazine and did not interact with the participant. When rumination occurred, the therapist made a disapproving statement (e.g., “stop that”). In the escape condition, the therapist presented a receptive labeling task (Alex) or an object identification task (Tom) approximately every 30 s. Contingent on rumination, the therapist removed the task and ceased interacting with the participants for 15 s. In the play condition, the therapist provided the participant with continuous access to a standing mirror (Alex) or picture books (Tom) and did not interact with him. (The mirror and picture books were judged to be preferred objects by direct-care staff familiar with Alex and Tom.) Finally, in the no-interaction condition, the therapist sat at a distance from the participant and did not interact with him.

Intervention Evaluation

The effects of intervention were evaluated using a multielement design with Alex and a combined multielement and reversal design with Tom. During each session, the therapist sat beside the participant and, other than the procedures described below, did not interact with him. To judge whether intervention was influenced by the presence of preferred stimuli, Alex had continuous access to the standing mirror during sessions (stimuli present) but picture books were omitted with Tom (stimuli absent).

Alex

Intervention 1 sessions (15 min) included noncontingent presentation of a food or liquid item on a fixed-time (FT) 30-s schedule. The food items were either one Cheez-It® cracker or one 10th of a Nutri-Grain® bar, and the liquid items were 1 oz of fruit juice or water. These food and liquid items were selected because Alex readily consumed them (based on observation and reports by direct-care staff preceding the study). In addition, a control condition, identical to that conducted during the functional analysis, was included. During Intervention 2, the therapist presented only the fruit juice on the FT 30-s schedule, but the amount was reduced to 0.5 oz and the session duration was extended to 30 min. We included this phase to determine if intervention fading (reducing fluid amount and increasing session duration) influenced the results obtained with the most effective consumable stimulus.

Tom

Intervention evaluations (20 min) included noncontingent presentation of a food or liquid item on an FT 30-s schedule and a third condition of continuous access to a chew ring. The food item was one third of a pretzel, and the liquid item was 1 oz of fruit punch. The food and liquid items were selected because Tom readily consumed them (based on observation and reports of direct-care staff preceding the study). The chew ring was a circular infant teething ring that the therapist presented to Tom when the session began. Baseline sessions were identical to the no-interaction condition of the functional analysis (the therapist was present but preferred stimuli and interaction were not provided).

Results and Discussion

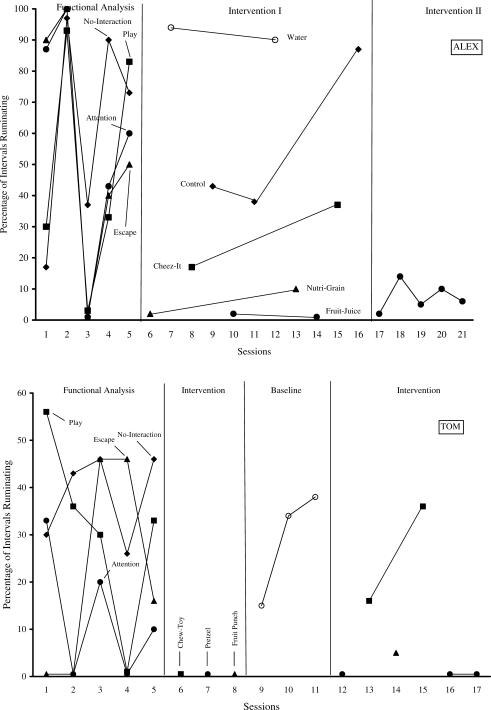

Figure 1 shows the percentage of intervals in which rumination was recorded during functional analyses and intervention evaluations. For Alex, rumination occurred at moderate to high levels across functional analysis conditions: attention (M = 62%), escape (M = 50%), play (M = 46%), and no interaction (M = 64%). Results from the Intervention 1 evaluation showed that rumination was lowest when he consumed fruit juice (M = 0.5%), followed by the Nutri-Grain® bar (M = 5.5%), Cheez-It® cracker (M = 25%), and water (M = 92%). During control conditions, rumination averaged 56%. When Intervention 2 was initiated (a reduced amount of fruit juice was presented and session duration was increased), average rumination was 7.2%.

Figure 1.

Percentage of intervals with rumination during functional analyses and intervention evaluations for Alex (top) and Tom (bottom).

For Tom, rumination occurred at moderate to high levels across conditions, with the highest levels occurring during the no-interaction condition (M = 38%) relative to attention (M = 13%), escape (M = 22%), and play (M = 33%). During the first three sessions of the intervention evaluation, Tom did not demonstrate rumination with food, liquid, or the chew ring. Rumination increased when intervention was withdrawn, averaging 29%. When the intervention was reimplemented, rumination was 5% during one session with liquid, averaged 27% during two sessions with the chew ring, and was 0% during three sessions with food.

As noted, the present research is the first to incorporate a preintervention functional analysis of rumination. Because results of the functional analysis for both participants showed moderate to high levels of rumination across conditions and rumination was not differentially high during social test conditions, these findings suggest that rumination was maintained by automatic reinforcement. We acknowledge that because the functional analyses featured rapidly alternating 5-min segments, it is possible that the undifferentiated outcomes were due to a lack of discrimination among conditions and not automatic reinforcement. These results might have been clarified by either conducting an extended series of no-interaction sessions or having discriminative stimuli associated with each condition. In addition, the control condition of the functional analysis differed from typical methodology because noncontingent attention was not presented (Iwata et al., 1982/1994).

Our brief intervention evaluation was similar to a competing-items assessment, a procedure that has been used to identify items that may compete with problem behavior that is not socially mediated (Piazza et al., 1998). The sessions were time efficient, ensuring that a lengthier course of intervention would not incorporate ineffective stimuli. For Alex, presenting fruit juice on a noncontingent FT schedule eliminated rumination during the initial intervention phase. The two food conditions (Cheez-It® and Nutri-Grain® bar) also reduced rumination relative to control. The alternative liquid (water) was ineffective. In the second intervention when fruit juice was offered exclusively, rumination increased only slightly from the preceding phase, perhaps because the quantity of fruit juice was reduced and session length was increased.

The first intervention with Tom demonstrated that food, liquid, and a chew ring eliminated rumination. During baseline, rumination increased to levels observed during the no-interaction condition of the functional analysis. In a replication phase, rumination remained absent when food was presented, increased slightly with liquid, and recovered to baseline levels with the chew ring. We included the chew ring condition to compare food and liquid with a stimulus that could not be consumed. One interpretation is that the chew ring initially had a novelty effect that diminished with repeated exposure, whereas food and liquid had a more sustained reductive effect.

Although the supplemental feeding intervention was effective, the mechanism of change is unclear. The food and liquid items may have induced satiation or provided sensory stimulation similar to rumination (reinforcer substitutability). During intervention sessions, Alex readily consumed the two food items and fruit juice but ingested the water infrequently. Observation also confirmed that Tom consistently accepted the food and liquid items and intermittently mouthed the chew ring. Unfortunately, we did not measure rumination following intervention sessions to determine whether consumption simply delayed the behavior. Finally, the presence of a preferred stimulus with Alex and the absence of a preferred stimulus with Tom did not appear to influence intervention.

Our research had several limitations: The preference assessment was limited to staff judgment, the evaluation was restricted to the lunch meal, the intervention was not extended throughout the day, and there was no formal measurement of procedural fidelity. Further study of supplemental feeding interventions for rumination also would benefit from more objective measurement of food and liquid consumption. For example, in this study the participants were given standard-portion lunch meals prepared at school, but the amount they ate was not measured. Clearly, presession food consumption could influence rumination and the effectiveness of the intervention procedures we evaluated. Acknowledging these constraints, it appears that supplemental feeding can reduce postmeal rumination and may be dependent on the type of food and liquid given. Additional research should continue to examine the contribution of brief functional analyses, procedural parameters (e.g., quantity and schedule of presentation), and maintenance evaluation while treatment is systematically withdrawn.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted at the May Center for Child Development.

References

- Dudley L.L, Johnson C, Barnes S. Decreasing rumination using a starchy food satiation procedure. Behavioral Interventions. 2002;17:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Heering P.W, Wilder D.A, Ladd C. Liquid rescheduling for the treatment of rumination. Behavioral Interventions. 2003;18:199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A, Dorsey M.F, Slifer K.J, Bauman K.E, Richman G.S. Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:197–209. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197. (Reprinted from Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 2, 3-20, 1982) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza C.C, Fisher W.W, Hanley G.P, LeBlanc L.A, Worsdell A.S, Lindauer S.E, et al. Treatment of pica through multiple analyses of its reinforcing functions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:165–189. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rast J, Johnston J.M, Drum C, Conrin J. The relation of food quantity to rumination behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1981;14:121–130. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1981.14-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]