Abstract

While cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in heart failure (HF) patients, the fundamental mechanisms for the efficacy of CRT are poorly understood. The lack of understanding of these basic mechanisms represents a significant barrier to our understanding of the pathogenesis of HF and potential recovery mechanisms. Our purpose was to determine cellular mechanisms for the observed improvement in chronic HF after CRT. We used a canine model of chronic nonischemic cardiomyopathy. After 15 months, dogs were randomized to continued RV tachypacing (untreated HF) or CRT for an additional 9 months. Six minute walk tests, echocardiograms, and electrocardiograms were done to assess the functional response to therapy. Left ventricular (LV) midmyocardial myocytes were isolated to study electrophysiology and intracellular calcium regulation. Compared to untreated HF, CRT improved HF-induced increases in LV volumes, diameters and mass (p<0.05). CRT reversed HF-induced prolongations in LV myocyte repolarization (p<0.05) and normalized HF-induced depolarization (p<0.03) of the resting membrane potential. CRT improved HF-induced reductions in calcium (p<0.05). CRT did not attenuate the HF-induced increases in LV interstitial fibrosis. Using a translational approach in a chronic HF model, CRT significantly improved LV structure; this was accompanied by improved LV myocyte electrophysiology and calcium regulation. The beneficial effects of CRT may be attributable, in part, to improved LV myocyte function.

Keywords: Heart failure, cardiac resynchronization, action potential, calcium

Introduction

Heart Failure (HF) is defined as an inability of the heart to support the metabolic and physiologic needs of the body (Ventura-Clapier et al., 2004). This syndrome is often a progressive disease, which includes changes in physiology, cellular biology and neurohormonal regulation irrespective of the initial etiology (Francis, 2001). Newly diagnosed HF patients have a mortality rate of 10% a year, and if hospital admission is warranted, the one year mortality rate may be close to 30% (Patterson and Adams, Jr. 1993). Although there have been many significant advances in HF medical therapy, this disease state is a major concern and its incidence continues to rise in the US while most other forms of heart disease are in decline. There is clearly a need to better define the key mechanisms of HF progression in order to develop improved therapeutic strategies.

A hallmark feature of chronic HF progression in humans and animal models is the time-dependent adaptation of myocardium, leading to changes in cardiac myocyte performance or survival, and changes in myocardial tissue composition. Specifically, ventricular chamber dilation, and myocyte hypertrophy are all well recognized features of cardiac adaptations in HF (Dhalla et al., 2006), and can be considered favorable adaptations for acute increases in cardiac demand, but are also likely contributors to progressive pump failure which may be deleterious over the long term. Long-term or chronic-progressive HF (CPHF) has been less extensively studied in controlled large animal studies. Cumulative evidence, now suggests that spatial as well as temporal signaling will have a significant impact on long-term patient outcomes, but chronic large animal studies remain difficult and often cost-prohibitive. The scarcity of such information represents a fundamental gap in our knowledge base, precluding our scientific understanding of cellular mechanisms in HF patients.

Therapies shown to provide long term efficacy in CPHF typically reduce or reverse one or more cardiac remodeling features (e.g., decreased chamber dimension, reduction in hypertrophy), and it is clear that cardiac tissue characteristics, rather than hemodynamic endpoints, are better predictors of long term therapeutic value for chronic HF (Frigerio and Roubina, 2005). Recent evidence suggests that cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) with bi-ventricular pacing results in improved left ventricular ejection fraction, New York Heart Association class, exercise capacity, and quality of life (Berger et al., 2005; Rao et al., 2007). Findings of the COMPANION and CARE HF trials indicate that CRT reduces all-cause mortality and hospitalization in HF patients (Epstein, 2005; Leclercq and Daubert, 2003). CRT can also improve cardiac structure and function (e.g., decreased LV diameter, and increased ejection fraction), suggesting that it elicits favorable effects on remodeling mechanisms contributing to HF progression (Bristow et al., 2004; Cleland et al., 2005; Rivera and Bristow, 2005). This phenomenon of ‘reverse remodeling’ elicited in many patients receiving CRT therapy is now well-documented, but the specific cellular mechanisms that contribute to the observed clinical gains have not been identified.

We have recently established a dog model of nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy which involves chronic RV tachypacing for over one year, leading to sustained reductions in LV contractility, ventricular dilation and hypertrophy, and ventricular dyssynchrony. Prolongation of in vivo repolarization and impaired exercise capacity were also observed (Nishijima et al., 2005). Currently, no previous reports have described an animal preparation for mechanistic studies of CRT in vivo. Since this large animal model of HF mimics the patient population most appropriate to receive CRT (decreased ejection fraction with an intraventricular conduction delay), we postulated that it would be appropriate for CRT investigations. Here we tested the hypothesis that this established canine model of CPHF would be useful for the study of CRT-induced reverse remodeling effects. We investigated potential mechanisms of CRT effects in vivo and ex vivo, with a specific focus on mechanisms known to be altered in HF patients (LV performance, chamber dilation, hypertrophy, and fibrosis). In addition to tissue-level adaptations during HF, numerous studies have documented alterations within myocytes, particularly with respect to cellular electrophysiology and intracellular calcium handling. We therefore examined the effects of chronic CRT on these aspects of myocyte function to test the hypothesis that CRT elicits favorable effects on myocyte action potentials and calcium handling.

Materials and Methods

Animal model and study design

All animal procedures were approved by the Ohio State University Institutional Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee and conform to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). A total of 11 dogs were investigated in this study (ages 1.5 – 3 years; weights 20-33 kg), using methods we have previously described (Nishijima et al., 2005). All dogs were initially verified to have normal cardiac function by examination by a veterinary cardiologist, followed by ECG (Biopac, MP100 software, Biopac Systems Inc, Santa Barbara, CA), 2-D and M-mode echocardiograms (GE Vivid 7) during butorphanol (0.5 mg kg-1 intramuscularly) sedation. These procedures were conducted during normal sinus rhythm.

A cohort of 7 dogs were initially enrolled in the study, wherein initial baseline measurements were collected, followed by a sequential continuous pacing of the RV for 15 months, leading to a stable and reproducible dilated cardiomyopathy. Pacing was performed at: 180 bpm for 2 weeks, 200 bpm for 6 weeks, 180 bpm for 2 months, 160 bpm for 6 months, then 120 bpm thereafter to achieve and maintain stable, clinically moderate LV dysfunction (i.e., increased respirations, cardiomegaly, mitral regurgitation, and left ventricular fractional shortening of less than 12%), as previously reported (Nishijima et al., 2005). This pacing paradigm has been found to result in stable, minimally reversible LV dysfunction. Notably, the final rate of 120 bpm is within the normal canine daily heart rate range (Hamlin et al., 1967).

After HF was established for 15 months via RV tachypacing, animals were randomized to receive either continued RV pacing (fixed rate of 120bpm, n=4) or CRT by biventricular pacing (fixed rate of 120bpm, n=3) for an additional 9 months (i.e., a total duration of 24 months). At the conclusion of the study, animals were sacrificed and cardiac tissues were rapidly collected for tissue and myocyte studies. An additional 4 dogs were also included as controls, these dogs were studied in vivo and sacrificed in parallel.

Biventricular pacemakers were implanted via a left lateral hemithoracotomy (the 5th intercostal space) and pericardiotomy. The heart was exposed and a left ventricular pacing lead (Medtronic) was sutured to the epicardium (posterior-lateral wall), and the chest incision was closed. A bipolar intravenous atrial pacing lead (Medtronic) was inserted through the jugular vein into the right atrium for atrial endocardial pacing. The pacing leads used for chronic RV pacing were also used for CRT with a upgraded generator (Insync III 8042 pacemaker, Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN). CRT was initiated (by pacing the right atrium, right ventricular endocardium, and left ventricular epicardium) to attenuate LV segmental wall dysynchrony. Atrioventricular (AV) delays were set at 90 ms, 100 ms, and 110 ms, and optimized using established criteria.. RV-LV delays were set at 12 ms, 4 ms and 4 ms, respectively, based on optimization by tissue velocity imaging to minimize mid-ventricular LV dysynchrony.

In vivo cardiac performance

Exercise tolerance

Serial six minute walk tests (6MWT) were done as previously described in a non-sedated canines (Boddy et al., 2004). All dogs were conditioned to the protocol, prior to baseline data acquisition.

Echocardiography and Tissue Doppler Imaging

Two-dimensional, M-mode, and tissue doppler echocardiography (GE Vivid-7 Echocardiograph System, 3-MHz sector transducer) were performed on sedated dogs on a customized table. M-mode and 2-dimensional images were obtained to quantify and estimate LV cardiac size, LV systolic, diastolic function and LV mass. Data were obtained during brief periods where the pacemaker was inactivated. All measurements were made in triplicate and averaged by a single-blinded investigator. Internal controls were used to verify reproducibility of echocardiographic and electrocardiogram measurements.

Tissue Doppler imaging was obtained from apical 4- and 2-chamber image planes, optimized for the LV inlet using GE Vivid-7 tissue analysis software. Segmental wall motion analysis was performed at mid- ventricular LV to assess dyssynchrony of the septum and lateral free wall. Each sample volume was anchored to the tissue and tracked during the cardiac cycle and sample size volume approximated diastolic thickness. The time (ms) from the onset of the QRS to the peak, early systolic velocity was determined for each segment to determine dyssynchronous activation, where dyssynchrony = [(QRS onset to maximum systolic movement)septal − (QRS onset to maximum systolic movement)lateral].

Electrocardiograms

Butorphanol sedation (0.5 mg/kg, intramuscular) was administered to minimize motion artifact. Data were obtained during brief periods where the pacemaker was inactivated. Electrocardiograms were recorded using a physiologic data acquisition system (MP100, Biopac Systems), at a rate of 2000 Hz. The QT interval was rate corrected using Fridericia’s formula (Hamlin et al., 2003). Measurements were averaged from 6 consecutive cycles.

Myocardial Interstitial Fibrosis

Left ventricular anterior free wall was formalin fixed and embedded in paraffin using standard procedures, and sectioned at 5 microns thickness. Tissue sections were then stained with Masson’s trichrome and automated digital image analysis methods were used to determine the prevalence of interstitial fibrosis as previously described (Mihm et al., 2001; Mihm et al., 2001). These approaches provided objective and reproducible endpoints with minimal operator involvement, with intra-observer and inter-observer variability less than 3% for each parameter (Mihm et al., 2001).

Isolated Myocyte Investigations

After completing the in vivo phase of the study, ventricular myocytes were isolated using established protocols (Kubalova et al., 2005). This typically yielded ~70% quiescent myocytes with sharp margins. The myocytes were incubated at room temperature in a buffer containing (in mM) NaCl 118, KCl 4.8, MgCl2 1.2, KH2PO4 1.2, glutamine 0.68, glucose 10, pyruvate 5, CaCl2 1, along with 1 μmol l-1 insulin, and 1% BSA until use. Only quiescent myocytes with sharp margins and clear striations were used for electrophysiologic studies.

Myocyte Action Potentials

Myocytes were placed in a laminin coated chamber and superfused with bath solution containing (in mM): 135 NaCl, 5 MgCl2, 5 KCl, 10mM Glucose, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 5mM HEPES, pH 7.40 with NaOH; at a temperature of 36 ± 0.5°C. Borosilicate glass micropipettes were filled with pipette solution containing (in mM): 100 K+-aspartate, 40 KCl, 5 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 5 HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. Perforated whole cell patch clamp (using amphotericin B) was used to minimize alterations in intracellular milieu. Recordings were made with an Axon 200b amplifier using pClamp (v.8) software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA).

Myocyte Calcium Measurements

All calcium measurements were made using previously described methods (Kubalova et al., 2005). Action potential recordings were performed with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, USA) and pClamp (9.2) software. The resting membrane potential was clamped at -75 mV and cells were stimulated at a frequency of 0.5 Hz. The external solution contained (in mmol/L) NaCl 140, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 1.0, MgCl2 0.5, HEPES 10, and glucose 5.6, pH 7.3. Patch pipettes were filled with a solution that contained (in mmol/L) K-aspartate 90, KCl 50, Na2ATP 3, MgCl2 3.5, HEPES 10, and Fluo-3 K+-salt 0.05, pH 7.3 Experiments were performed at 20-23 °C.

Intracellular Ca imaging was performed using an Olympus Fluoview 1000 laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with an Olympus 60 × 1.4 N.A. oil objective. Fluo-3 was excited by the 488-nm line of an argon-ion laser, and the fluorescence was acquired at wavelengths >510 nm in the line-scan mode of the confocal system at the rate of 2 ms per scan.

Statistical comparisons

Comparisons of sequential measurements from corresponding baseline values were made using paired t-tests, whereas comparisons between treatment groups were made by unpaired t-tests or ANOVA followed by Student-Neuman-Keuls post-tests where appropriate.

Results

Shown in Table 1 are physiological changes induced by 15 months of continuous RV tachypacing in dogs, leading to stable and reproducible HF. Similar to previous reports the tachypacing protocol produced significant reductions in LV contractility, and evidence of chamber dilation and hypertrophy, and dyssynchrony at the mid-ventricular level. There were no elevations in Troponin C, Troponin I, or C-reactive protein (data not shown).

Table 1.

Description of Heart Failure Dogs Prior to Randomization

| Baseline | RV tachypacing

15 months |

|

|---|---|---|

| LV FS (%) | 37.0±1.0 | 12.9±1.1* |

| LV End diastolic volume (ml) | 68 ± 4 | 178 ± 54* |

| LV End systolic volume (ml) | 22 ± 2 | 129 ± 14* |

| LV mass (g) | 110 ± 10 | 218 ± 17* |

| QRS (ms) | 53 ± 2 | 76 ± 3* |

| QTc (ms) | 259 ± 7 | 278 ± 5* |

| Mid-ventricular dyssynchrony (ms) | 15.3 ± 4.4 | 46.4 ± 15* |

| 6 minute walk test (m) | 514 ± 102 | 388 ± 149* |

Mean ± SEM, n=7.

, Significant difference from corresponding baseline values.

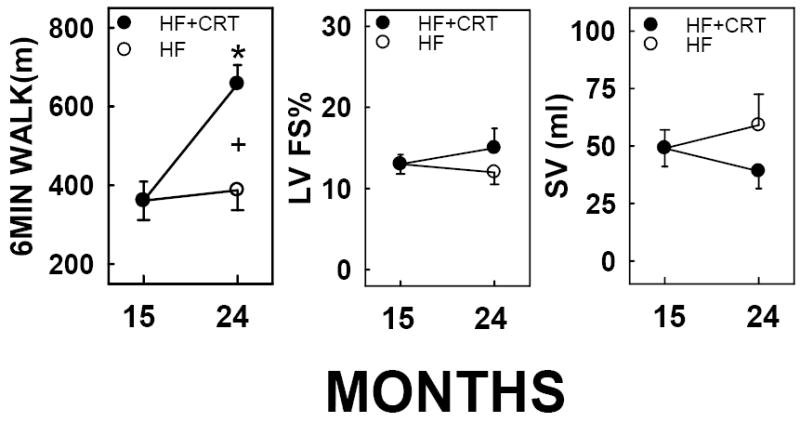

After establishing HF via RV tachypacing for 15 months, dogs were randomized to receive either continued single lead RV pacing (120bpm) or CRT (120bpm), for an additional 9 months (from months 15 to 24). Shown in Figure 1 are the effects of single lead pacing (untreated HF) versus CRT (biventricular pacing-treated HF) on in vivo exercise capacity and LV performance. Dogs with untreated HF had a stable degree of exercise tolerance, corresponding to a 6 minute walk test of approximately 400 meters (Figure 1 left panel, open circles) during months 15-24. In contrast, CRT implantation resulted in significant improvement in 6 minute walk distance when compared to the pre-randomization period and when compared to the HF control at 24 months (Figure 1 left panel, closed circles, p<0.05 using pair-wise comparisons from 15 to 24 months). This degree of physical performance was similar to results observed for normal control dogs of similar age (data not shown). In contrast to improvements in exercise duration following 9 months of CRT, left ventricular FS% and LV stroke volume were not statistically different between treatment groups (Figure 1, middle and right panels). QRS complex duration and QTc (Fridericia correction) were also not different between treatment groups (data not shown).

Figure 1. Improved exercise duration following CRT in HF dogs.

Single lead pacing was performed from months 0-15 and at 15 months randomized to receive CRT (120bpm), or continued single lead pacing (120bpm), until 24 months. Mean ± SEM shown, n=3-7. *, statistically different from corresponding pre-randomization measurement at month 15; +, statistically significant difference between treatments at 24 months (p<0.05).

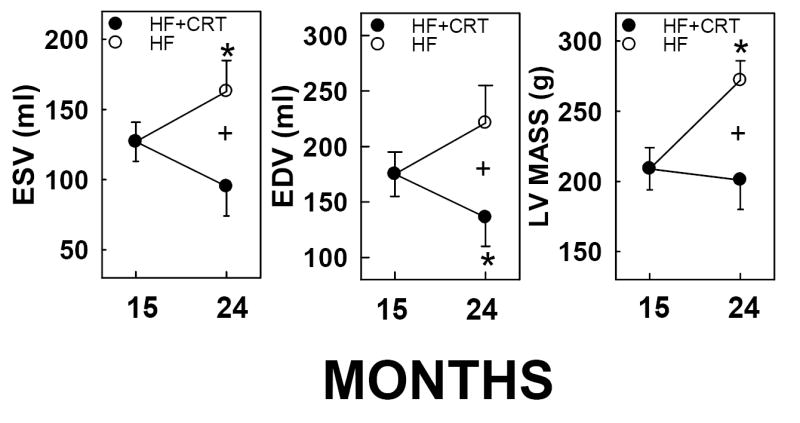

Shown in Figure 2 are comparisons of LV structure in untreated HF dogs versus CRT-treated HF dogs during the 9 month treatment period. Dogs with untreated HF had significant increases in LV volumes during systole and diastole, as well as increased LV mass (Figure 2, open circles, p<0.05 using pair-wise comparisons from 15 to 24 months). In contrast to the progressive LV dilation and hypertrophy in the untreated HF group, CRT caused significant reductions in these parameters from 15 to 24 months when comparing the treatment groups at 24 months.

Figure 2. Regression of LV hypertrophy and dilation induced by CRT in HF dogs.

Single lead pacing was performed from months 0-15 and at 15 months randomized to receive CRT (120bpm), or continued single lead pacing (120bpm), until 24 months. Mean ± SEM shown, n=3-7. *, statistically different from corresponding pre-randomization measurement at month 15; +, statistically significant difference between treatments at 24 months (p<0.05).

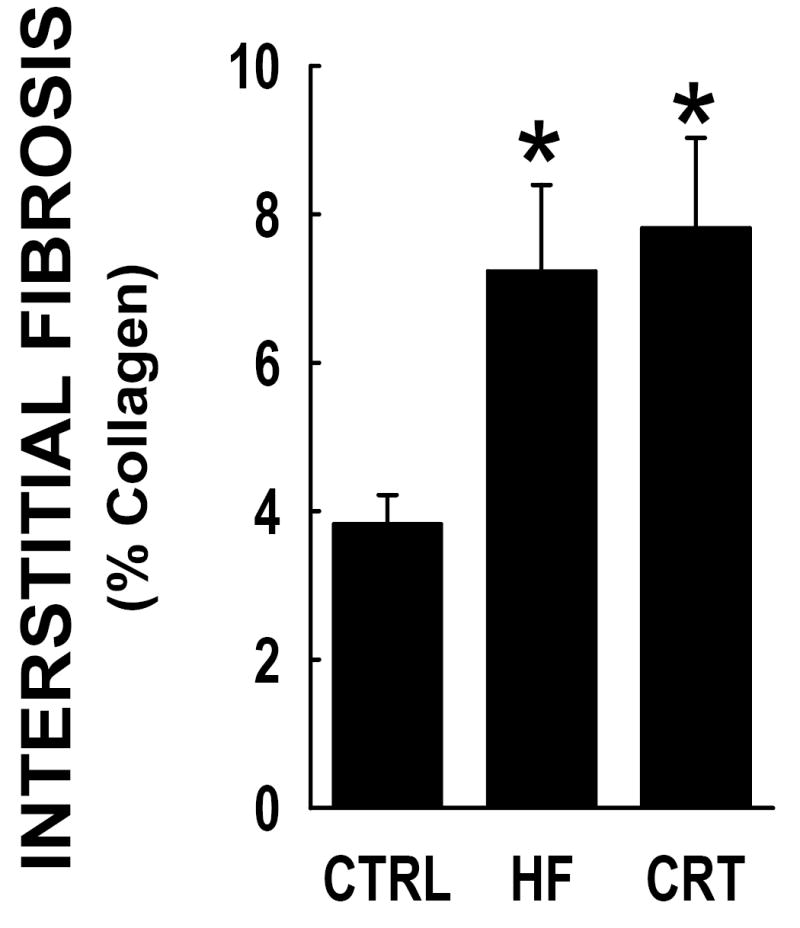

Figure 3 shows comparisons of interstitial fibrosis in anterior LV myocardium from controls, untreated HF dogs, or CRT-treated HF dogs. Full thickness myocardium was collected at 24 months in the HF dogs and compared to identical tissue sites from age-matched normal control dogs. In normal control myocardium the prevalence of interstitial matrix ranged from 2-4%, whereas the prevalence of interstitial fibrosis was approximately doubled in both HF groups (p<0.05); no difference between treatment groups was observed.

Figure 3. Interstitial fibrosis in LV was not reversed by CRT in HF dogs.

Anterior LV myocardium was collected at 24 months from normal control dogs (CTRL), single lead RV tachypaced (HF) or CRT from months 15 to 24. Percent of fibrosis determined by Masson’s Trichrome staining and automated image analysis. Each group represents n=59 LV tissue sampling sites. The HF dogs demonstrated a significant increase from the CTRL dog myocardium, whereas there was no statistical significant change in the observed fibrosis between the HF and the CRT tissues. *, statistically different from controls.

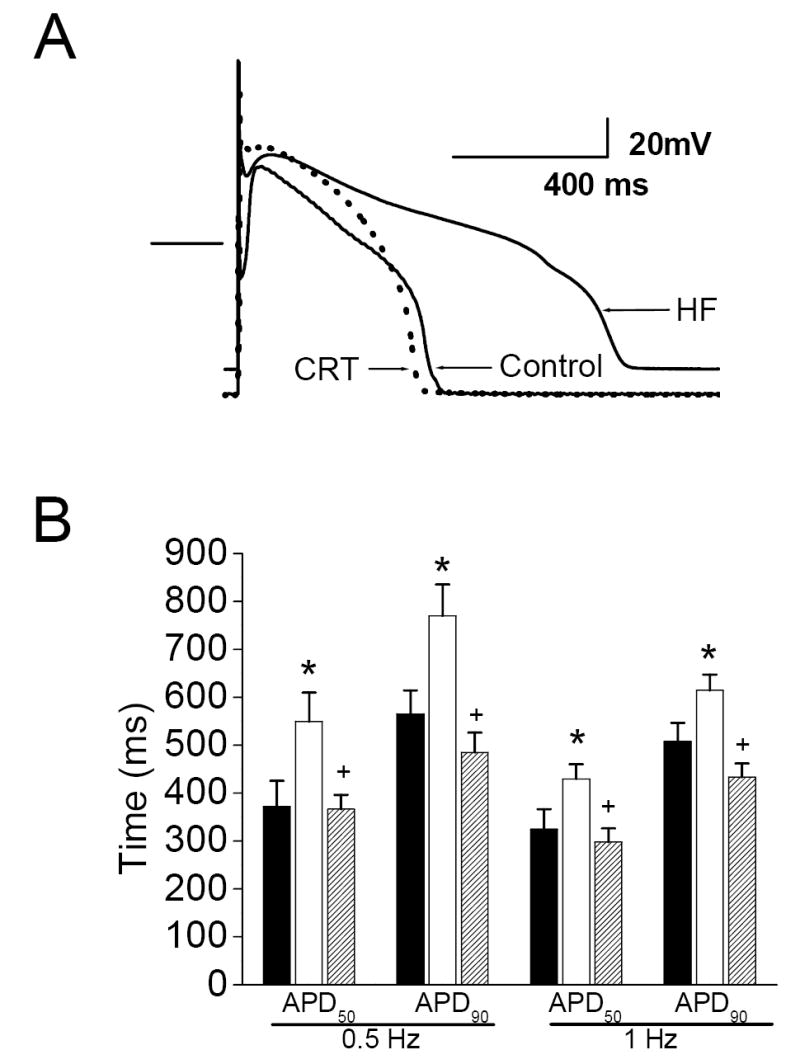

Shown in Figure 4 are comparisons of isolated cardiac myocyte action potentials from normal control dogs and both untreated HF or CRT-treated HF dogs. Dogs with untreated HF had significant increases in action potential duration at both 50% (APD50) and 90% (APD90) repolarization, when compared to myocytes from control dogs. These differences were observed at 0.5 Hz and 1.0 Hz. In contrast, myocytes isolated from HF dogs receiving CRT were found to have APDs that were not different from control, and significantly shorter than those in the untreated HF group. A significant reduction in the resting membrane potential was also observed in myocytes from the HF dogs compared to controls (-75.8 ± 1.3 mV vs. -79.4 ± 0.9 mV, respectively, p<0.03), whereas the resting potential in the CRT myocytes did not differ from controls (-76.9 ± 0.7 mV).

Figure 4. Ventricular myocyte repolarization is improved by CRT.

Left: A representative action potential from each group, recorded at 1 Hz. The bar indicates the zero current line. B. Action potential duration is prolonged after chronic HF, and restored toward normal after CRT (black bars: controls; red bars: HF; green bars: CRT; 6-9 cells per group). *- p<0.05 vs. Control, +- p<0.05 vs. HF.

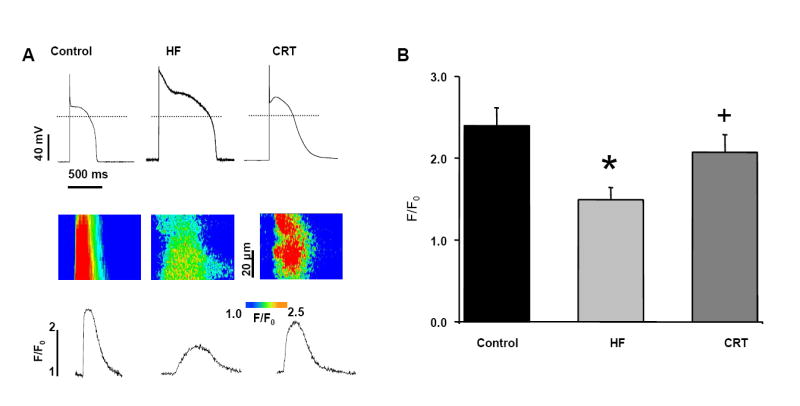

Figure 5 shows comparisons of intracellular calcium regulation from cardiac myocytes of normal control dogs and those receiving continuous single lead RV tachypacing (HF) or CRT. During periodic stimulation at 0.5 Hz, there was a prolongation of the APD (consistent with data reported in Figure 4) accompanied by a decrement in calcium transient amplitude in the untreated HF group (P<0.05). In contrast, the CRT group receiving CRT demonstrated a significant recovery in the calcium transient amplitude compared to the untreated HF group (P<0.05); CRT restored the calcium transient amplitude to levels which were not different from controls.

Figure 5. Action potential- induced calcium release is improved after CRT.

A. Representative images of action potentials (top) and simultaneous recordings of confocal line-scan images of Ca transients (middle) along with their spatial averages (bottom). Cardiac myocytes were stimulated with frequency 0.5 Hz. The dashed line indicates zero current. B. Averages of Ca transient amplitudes induced by periodic stimulation 0.5 Hz. n=10 from five control hearts; n=8 cells from four untreated HF hearts; n=5 from three CRT-treated HF hearts. *P < 0.05 compared to control; +P<0.05 vs. HF.

DISCUSSION

Of the five million Americans with CPHF, it is estimated that greater than 25% may qualify for CRT, with an average procedural cost of $40,000. These resources will be expended without the mechanism(s) of reverse-remodeling of CRT having been clearly elucidated. Additionally, for unknown reasons, some patients respond remarkably well with CRT, while others have only modest or no improvement. To address these issues, we have established an animal model of chronic HF that mimics key features of the human HF(Nishijima et al., 2005), importantly the animal size permits us to evaluate CRT. Others have successfully used the canine right ventricular tachypacing model of HF (endorsed by the NIH as a standard nonischemic model), but in most previous reports others have employed a much higher pacing rate (200+bpm) for a shorter duration (2-4months), leading to a HF that is largely reversible after stopping the pacing stimulus (Kaab et al., 1996; Patel et al., 2000; Spragg et al., 2005). In our previous report, we showed that utilizing a ‘physiologically relevant’ pacing rate in dogs (120bpm), and extending the pacing duration far beyond that previously reported (10 months), we observed a more severe and more permanent form of HF than previous models using shorter pacing durations. In this study, we extended the pacing duration to 24 months, to allow for comparisons of single lead RV tachypacing (untreated HF) versus CRT treatment from months 15 to 24. Using this approach, we were able to investigate the influences of CRT at the organism, myocardial tissue, and isolated myocyte levels, relative to control dogs, and time-matched HF dogs studied in parallel.

As expected from our earlier work, the HF group had a constant degree of LV contractile dysfunction and exercise intolerance (Figure 1) from months 15 to 24. During this interval, however, we observed increases in LV ESV, EDV, and mass, demonstrating that progressive pathological remodeling proceeded (Figure 2). Increased prevalence of interstitial fibrosis was also observed in the HF dogs at 24 months when compared to control dog myocardium (Figure 3). Thus, the classical triad of pathological remodeling in HF (dilation, hypertrophy, and fibrosis) was present in this chronic large animal preparation.

The LV dysfunction and organ remodeling observed in HF dogs were also associated with impaired isolated myocyte repolarization and impaired excitation-contraction coupling compared to control myocytes. These findings are consistent with previous reports in various animal models, and consistent with the concept that impaired repolarization and calcium handling are common features of myocytes during chronic HF (Kaab et al., 1996; Pak et al., 1997; Tomaselli et al., 1994). We have previously reported that at shorter pacing durations in this canine model there is a substantial reduction in calcium transient amplitude and intra-SR calcium stores, which are attributable to an increase in diastolic calcium leak from the calcium release channels (ryanodine receptors) (Kubalova et al., 2005). Here we found similar evidence at 24 months, confirming that during non-ischemic cardiomyopathy and HF, abnormal calcium sequestration and/or release at the sarcoplasmic reticulum are key contributors to impaired myocyte excitation-contraction coupling.

Several CRT clinical trials have reported improvements in functional endpoints, such as 6MWT, New York Heart Association Classification, and quality of life (Abraham et al., 2002; Higgins et al., 2000; Linde et al., 2002). The improvement in LV dimensions and ejection fraction have been more variable between trials, than the more consistent findings of improvements in functional class and exercise capacity (Abraham et al., 2002; Bonanno et al., 2004; Rivera and Bristow, 2005). In our model, CRT caused an improvement in 6MWT, a method we had previously validated in chronic canine HF, and the 6MWT is an endpoint accepted by the American Food and Drug Administration for human HF trials (Boddy et al., 2004; Nishijima et al., 2005). A recent review of outcome measures in human clinical trials validated the 6MWT as a robust measure of improvement, despite its known limitations (Olsson et al., 2005). Notably, in previous studies, the 6MWT did not necessarily show concordance with echocardiographic indices of cardiac function (there was only 50% concordance with improved ejection fraction) (Olsson et al., 2005). This clinical discrepancy between exercise tolerance and LV contractility was mimicked in our dog model, since 6MWT was nearly doubled after nine months of CRT in HF dogs but FS% and stroke volume were statistically unchanged. In light of improvements in LV chamber dimensions (end systolic and diastolic dimensions) and LV mass, it is possible that gains in myocardial efficiency or improvements in diastolic perfusion may play a role in the enhanced exercise capacity.

Although CRT caused favorable influences on LV mass and chamber size, CRT had no impact on the extent of interstitial fibrosis in this HF model. This observation is consistent with clinical experience and suggests that some aspects of cardiac remodeling can be reversed (dilation, hypertrophy), whereas others (such as fibrosis) may not be. In light of this evidence it is possible that the extent of preexisting fibrosis within the ventricular myocardium could define the potential benefit derived from CRT therapy. In addition, these data would suggest that myocyte recovery is distinctly different from tissue remodeling, and that the observed clinical improvement during CRT is likely due to unique alterations in myocyte signaling and/or physiology, rather than fibrosis regression.

Coupled with favorable improvements caused by CRT observed in vivo, there were also significant improvements in cardiac myocyte E-C coupling ex vivo (same myocytes). For example, CRT reversed the action potential prolongation observed in HF, and resulted in action potential durations that did not differ from normal control myocytes. We also found a restabilization of the diastolic membrane potential subsequent to CRT. Our findings also support the concept that CRT has a direct impact on intracellular myocyte calcium handling, and that the clinical and/or functional gains observed in vivo may be mediated by improved calcium handling. The data from this study also suggest a potential role for improved calcium regulation at the sarcoplasmic reticulum, or more specifically a reduction in ryanodine receptor ‘leak’ during CRT, since this specific abnormality was previously reported in this chronic HF (Kubalova et al., 2005)

This report provides the first translational-evidence that HF-induced abnormalities in the integrated electrophysiologic response to stimulation (the action potential) and excitation-contraction coupling can be reversed or attenuated with CRT. These data suggest that CRT contributes to improved in vivo function, in part, through improved myocyte function, specifically in modulation of SR calcium release. This specific intra-myocyte effect on cytosolic calcium could potentially be responsible for much of the effects observed in vivo, since impaired calcium release during HF results in contractile dysregulation is known to result in activation of hypertrophic signaling in cardiac myocytes (Wilkins and Molkentin, 2004) and contribute to myocardial stiffness and metabolic inefficiency.

A few limitations exist in this study. No “sham” CRT group was used, rather a continued RV pacing group was used as the control. All HF dogs and CRT dogs were maintained at a fixed heart rate of 120 bpm. This heart rate is well within the daily range in normal dogs (Hamlin et al., 1967). We have previously reported that this heart rate is sufficient to maintain a stable impairment of LV function, after months of RV tachypacing (Nishijima et al., 2005). It is possible that the heart rate of 120 bpm may have attenuated the CRT-induced reverse remodeling in our dogs, compared to what may occur in humans with a normal heart rate. However, heart rate is a critical determinant of cardiomyopathy in this model, necessitating a matched heart rate for the two groups. This heart failure model is a non-ischemic (minimally reversible) cardiomyopathy model, and it is unknown if our observations would extend to an ischemic cardiomyopathy population or to true “end-stage” heart failure. Moreover, our treated animals were managed with CRT alone, and any potential interactions or synergies between pharmacologic HF therapies and CRT were not addressed. Due to technical limitations with the placement of the LV pacing lead, we placed the lead on the posterior-lateral epicardium of the left ventricle. The majority of patients have the LV pacing lead placed via the coronary sinus. Our methodology utilized in these experiments did ultimately replicate the site used in most HF patients (posterior-lateral LV wall), but activation was initiated epicardially. While the epicardial lead placement does not replicate the site used in the majority of patients, we note that this approach is used in a subset of patients with difficult lead placements. Most importantly, either approach to lead placement results in electrical activation of the LV epicardium and similar gains in ventricular synchrony.

Conclusion

These studies show that that the dog model or HF is appropriate for mechanistic investigations of CRT and recapitulates the phenomenon of reverse remodeling described in heart failure patients. Our observations suggest that in vivo function and myocyte calcium regulation are linked, not only during the development of heart failure, but also during reverse remodeling, and that CRT may directly modulate myocyte excitation-contraction coupling. In the future it may be possible to further elucidate specific signaling mechanisms which are linked to myocyte contractile performance and a change in functional parameters. Additional studies will be required to further elucidate the mechanistic causes of improved in vivo function during CRT, and will provide further insights into which aspects of heart failure pathogenesis are reversible either through improved ventricular synchrony or by yet undiscovered signaling mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures:

Abraham: Medtronic: consultant and research grants

Feldman: Medtronic: consultant and research support

Supported in part by grants from the NIH: HL084498 (D.S.F.), HL074045 and HL063043 (S.G.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abraham WT, Fisher WG, Smith AL, Delurgio DB, Leon AR, Loh E, Kocovic DZ, Packer M, Clavell AL, Hayes DL, Ellestad M, Trupp RJ, Underwood J, Pickering F, Truex C, McAtee P, Messenger J. Cardiac resynchronization in chronic heart failure. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(24):1845–1853. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger T, Hanser F, Hintringer F, Poelzl G, Fischer G, Modre R, Tilg B, Pachinger O, Roithinger FX. Effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy on ventricular repolarization in patients with congestive heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiololgy. 2005;16(6):611–617. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2005.40496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddy KN, Roche BM, Schwartz DS, Nakayama T, Hamlin RL. Evaluation of the six-minute walk test in dogs. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 2004;65(3):311–313. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2004.65.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno C, Ometto R, Pasinato S, Finocchi G, La Vecchia L, Fontanelli A. Effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy on disease progression in patients with congestive heart failure. Italian Heart Journal. 2004;5(5):364–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J, Krueger S, Kass DA, De Marco T, Carson P, DiCarlo L, DeMets D, White BG, DeVries DW, Feldman AM. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350(21):2140–2150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland JG, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D, Kappenberger L, Tavazzi L. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352(15):1539–1549. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhalla NS, Dent MR, Tappia PS, Sethi R, Barta J, Goyal RK. Subcellular remodeling as a viable target for the treatment of congestive heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2006;11(1):31–45. doi: 10.1177/107424840601100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein AE. New insights into cardiac resynchronization therapy. Clinical Cardiology. 2005;28(11 Suppl 1):I45–I50. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960281308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis GS. Pathophysiology of chronic heart failure. American Journal of Medicine. 2001;110(Suppl 7A):37S–46S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigerio M, Roubina E. Drugs for left ventricular remodeling in heart failure. American Journal of Cardiology. 2005;96(12A):10L–18L. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin RL, Olsen I, Smith CR, Boggs S. Clinical relevancy of heart rate in the dog. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1967;151(1):60–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins SL, Yong P, Sheck D, McDaniel M, Bollinger F, Vadecha M, Desai S, Meyer DB. Biventricular pacing diminishes the need for implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy. Ventak CHF Investigators. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2000;36(3):824–827. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00795-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaab S, Nuss HB, Chiamvimonvat N, O’Rourke B, Pak PH, Kass DA, Marban E, Tomaselli GF. Ionic mechanism of action potential prolongation in ventricular myocytes from dogs with pacing-induced heart failure. Circulation Research. 1996;78(2):262–273. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubalova Z, Terentyev D, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Nishijima Y, Gyorke I, Terentyeva R, da Cunha DN, Sridhar A, Feldman DS, Hamlin RL, Carnes CA, Gyorke S. Abnormal intrastore calcium signaling in chronic heart failure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science U S A. 2005;102(39):14104–14109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504298102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq C, Daubert JC. Cardiac resynchronization therapy is an important advance in the management of congestive heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 2003;14(9 Suppl):S27–S29. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.14.s9.9.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde C, Leclercq C, Rex S, Garrigue S, Lavergne T, Cazeau S, McKenna W, Fitzgerald M, Deharo JC, Alonso C, Walker S, Braunschweig F, Bailleul C, Daubert JC. Long-term benefits of biventricular pacing in congestive heart failure: results from the MUltisite STimulation in cardiomyopathy (MUSTIC) study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;40(1):111–118. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihm MJ, Coyle CM, Schanbacher BL, Weinstein DM, Bauer JA. Peroxynitrite induced nitration and inactivation of myofibrillar creatine kinase in experimental heart failure. Cardiovascular Research. 2001;49(4):798–807. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00307-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihm MJ, Yu F, Carnes CA, Reiser PJ, McCarthy PM, Van Wagoner DR, Bauer JA. Impaired myofibrillar energetics and oxidative injury during human atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2001;104(2):174–80. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishijima Y, Feldman DS, Bonagura JD, Ozkanlar Y, Jenkins PJ, Lacombe VA, Abraham WT, Hamlin RL, Carnes CA. Canine nonischemic left ventricular dysfunction: a model of chronic human cardiomyopathy. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2005;11(8):638–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JH, Adams KF., Jr Pathophysiology of heart failure. Pharmacotherapy. 1993;13(5 Pt 2):73S–81S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson LG, Swedberg K, Clark AL, Witte KK, Cleland JG. Six minute corridor walk test as an outcome measure for the assessment of treatment in randomized, blinded intervention trials of chronic heart failure: a systematic review. European Heart Journal. 2005;26(8):778–793. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak PH, Nuss HB, Tunin RS, Kaab S, Tomaselli GF, Marban E, Kass DA. Repolarization abnormalities, arrhythmia and sudden death in canine tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1997;30(2):576–584. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel HJ, Pilla JJ, Polidori DJ, Pusca SV, Plappert TA, Sutton MS, Lankford EB, Acker MA. Ten weeks of rapid ventricular pacing creates a long-term model of left ventricular dysfunction. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2000;119(4 Pt 1):834–841. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(00)70021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao RK, Kumar UN, Schafer J, Viloria E, De Lurgio D, Foster E. Reduced ventricular volumes and improved systolic function with cardiac resynchronization therapy: a randomized trial comparing simultaneous biventricular pacing, sequential biventricular pacing, and left ventricular pacing. Circulation. 2007;115(16):2136–2144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.634444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera DA, Bristow MR. Cardiac resynchronization--a heart failure perspective. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology. 2005;10(4 Suppl):16–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2005.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spragg DD, Akar FG, Helm RH, Tunin RS, Tomaselli GF, Kass DA. Abnormal conduction and repolarization in late-activated myocardium of dyssynchronously contracting hearts. Cardiovascular Research. 2005;67(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli GF, Beuckelmann DJ, Calkins HG, Berger RD, Kessler PD, Lawrence JH, Kass D, Feldman AM, Marban E. Sudden cardiac death in heart failure. The role of abnormal repolarization. Circulation. 1994;90(5):2534–2539. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.5.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura-Clapier R, Garnier A, Veksle V. Energy metabolism in heart failure. Journal of Physiology. 2004;555(1):1–13. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.055095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins BJ, Molkentin JD. Calcium-calcineurin signaling in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;322(4):1178–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]