Abstract

Fanconi anemia (FA) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by congenital abnormalities, progressive bone marrow failure, and cancer susceptibility. FA cells are hypersensitive to DNA crosslinking agents. FA is a genetically heterogeneous disease with at least 11 complementation groups. The eight cloned FA proteins interact in a common pathway with established DNA-damage-response proteins, including BRCA1 and ATM. Six FA proteins (A, C, E, F, G, and L) regulate the monoubiquitination of FANCD2 after DNA damage by crosslinking agents, which targets FANCD2 to BRCA1 nuclear foci containing BRCA2 (FANCD1) and RAD51. Some forms of hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] are implicated as respiratory carcinogens and induce several types of DNA lesions, including DNA interstrand crosslinks. We have shown that FA-A fibroblasts are hypersensitive to both Cr(VI)-induced apoptosis and clonogenic lethality. Here we show that Cr(VI) treatment induced monoubiquitination of FANCD2 in normal human fibroblasts, providing the first molecular evidence of Cr(VI)-induced activation of the FA pathway. FA-A fibroblasts demonstrated no FANCD2 monoubiquitination, in keeping with the requirement of FA-A for this modification. We also found that Cr(VI) treatment induced significantly more S-phase-dependent DNA double strand breaks (DSBs), as measured by γ-H2AX expression, in FA-A fibroblasts compared to normal cells. However, and notably, DSBs were repaired equally in both normal and FA-A fibroblasts during recovery from Cr(VI) treatment. While previous research on FA has defined the genetic causes of this disease, it is critical in terms of individual risk assessment to address how cells from FA patients respond to genotoxic insult.

Keywords: Carcinogen, Chromium, DNA interstrand crosslinks, Double strand breaks, Fanconi anemia, Genotoxin, H2AX, Homologous recombination, Human lung cells

1. Introduction

Fanconi anemia (FA) is a rare autosomal recessive disease characterized by congenital abnormalities, progressive bone marrow failure, and cancer susceptibility [1-4]. Acute myelogenous leukemia is the most common cancer in FA patients, although these patients are extremely likely to develop head and neck, gynecological, and/or gastrointestinal squamous cell carcinomas [1,5-7]. FA cells are hypersensitive to DNA crosslinking agents such as diepoxybutane, cisplatin, and mitomycin C (MMC) [2,4,8].

FA is a genetically heterogeneous disease with at least 11 complementation groups (A, B, C, D1, D2, E, F, G, I, J, and L) [9-11]. The eight cloned FA proteins (A, C, D1, D2, E, F, G, and L) interact in a common pathway and with established DNA-damage-response proteins, including BRCA1 and ATM [12-17]. In response to DNA damage and during normal DNA replication, six of the FA proteins (A, C, E, F, G, and L) assemble into a multisubunit nuclear complex, required for the activation (monoubiquitination) of the FANCD2 protein, which targets FANCD2 to BRCA1 nuclear foci containing BRCA2 (FANCD1) and RAD51 [10,11,18-21]. Inactivating mutations in any of these six proteins leads to inactivation of the complex and loss of FANCD2 monoubiquitination and targeting to nuclear foci [19,21-23]. Also, the FANCD2 protein is phosphorylated by ATM after ionizing radiation, thus contributing to the S-phase checkpoint [24,25].

Certain hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] compounds are well-established human carcinogens for which adverse health effects are usually associated with occupational exposure [26]. Epidemiological studies carried out in the U.K., Europe, Japan and the U.S. have consistently shown that workers in the chromate production industry have an elevated risk of respiratory disease, perforation of the nasal septum, development of nasal polyps, and lung cancer [27,28]. Ishikawa et al. [29] have reported that “hot spots” of particulate Cr accumulation at the bifurcations of the bronchi of chromate workers were present for more than 15 years after cessation of employment. The main environmental health concerns stem from the deposition of Cr in industrial waste either in the form of dissolved Cr released to surface waters or chromate slag used in landfills [30]. Cr as an atmospheric pollutant is generated by ferrochrome production, ore refining, refractory processing, combustion of fossil fuels, cement production, wearing of brake linings, welding and incineration of all types [30,31]. Environmental and occupational exposure to chromate continues to loom large as a major public health issue.

Epidemiologic, animal, and in vitro cell studies have consistently shown that particulate Cr(VI) compounds are the most relevant toxic and carcinogenic species [32]. Soluble Cr(VI) compounds are genotoxic and can induce gene mutations, sister chromatid exchanges, and chromosomal aberrations [33-35]. The structural DNA damage that results from Cr exposure is well-documented and includes Cr-monoadducts to both DNA bases and sugar-phosphate backbone, strand breaks, oxidized bases, DNA-protein crosslinks, abasic sites, Asc-Cr(VI) ternary adducts and DNA-Cr-DNA interstrand crosslinks (ICLs) [36-44] (for review, see [45]). The structural damage may lead to DNA and RNA polymerase arrest [46,47], mutagenesis [48-50], and/or altered gene expression [51-53] (reviewed in [45]). Moreover, we have recently shown that Cr(VI) induces S-phase-dependent DNA double strand breaks (DSBs), which are believed to be a consequence of ICL repair [54]. It is now well established that the mutagenic and transforming actions of Cr(VI) are only observed under dose/time treatment regimens which evoke some cellular toxicity (reviewed in [45]).

We have previously shown that FA-A cells are hypersensitive to Cr(VI)-induced apoptotic cell death and clonogenic lethality [55]. In the present study, we demonstrated Cr-induced monoubiquitination of FANCD2, thus providing the first molecular evidence of Cr(VI)-induced activation of the FA pathway. Moreover, we found that Cr(VI) induces a three- to four-fold increase in S-phase-dependent DSB formation, consistent with their Cr(VI) hypersensitivity, and presumably as a consequence of ICL repair. Finally, our data indicated that DSB repair was not compromised in FA-A cells, since the majority of DSBs were repaired in both FA-A and normal cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

CNTRL cells (Coriell Cell Repositories GM03349C, Camden, NJ) are normal human skin fibroblasts which were isolated from a 10-year-old black male. FA-A cells (Coriell Cell Repositories GM01309, Camden, NJ) are Fanconi anemia complementation group A human skin fibroblasts which were isolated from a 12-year-old black male. Both CNTRL and FA-A cells were maintained in MEM Eagle-Earle media (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Inc., Logan, UT), 2X essential and nonessential amino acids, vitamins, and 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). Cells were incubated in a 95% air, 5%CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37 °C.

2.2. Chromium preparation

Sodium chromate (Na2CrO4·4H2O) (J.T. Baker Chemical Company, Phillipsburg, NJ) was dissolved in double distilled water and sterilized through a 0.2 μm filter before use.

2.3. FANCD2 Western blot

Cells were seeded at 2 × 106 cells/150 mm dish and incubated for 24 h. The cells were treated with 0, 1, 3, or 6 μM Cr(VI) for 24 h. After 24 h, the cells were rinsed twice with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated for an additional 0, 4, 8, or 24 h in complete media. The cells were then harvested by gentle scraping in PBS containing phosphatase inhibitors (50 mM NaF and 1 mM NaOV). The cells were then lysed and sonicated in TGN buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Tween 20, 0.2% NP 40, 50 mM glycerophosphate, 10% glycerol, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM NaOV, 2 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 mM phenyl-methylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 mM dithiothreitol]. The cell lysates were clarified by microcentrifugation, and the supernatant fractions were saved. The proteins were resolved on 5% SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The membranes were probed with mouse monoclonal FANCD2 (FI17) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) primary antibody, which detects both unubiquitinated (S) and monoubiquitinated (L) FANCD2 isoforms, followed by HRP-linked secondary antibody (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The secondary antibody was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA) and Hyperfilm ECL (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The relative protein expression was analyzed by densitometry. The ratio of monoubiquitinated FANCD2 to unubiquitinated FANCD2 was determined for each treatment and divided by its vehicle control.

2.4. Immunostaining with γ-H2AX

Cells were seeded at 8 × 103 cells/well in 8-well chamber slides (Nunc Lab Tec, Fisher Scientific) and incubated for 24 h. The cells were treated with either 6 μM Cr(VI) or 100 ng/ml neocarzinostatin (NCS) for 1 h. After treatment, the cells were fixed with 100% methanol and were incubated overnight with a 1:500 dilution of a monoclonal antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), which specifically recognizes H2AX when it is phosphorylated at serine 139 (γ-H2AX), as previously described [54]. The cells were then incubated with goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1000 dilution), conjugated to Texas Red (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The cells were viewed with an Olympus BX-60 epi-fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY), configured with an Evolution MP digital CDD camera (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) and a Texas Red filter cube with excitation at 520-550 nm. Image-Pro Plus v4.5 software was used.

2.5. Flow cytometry with propidium iodide and γ-H2AX double staining

Cells were seeded at 1 × 106/100 mm dish and incubated for 24 h. The cells were treated with 0, 3, or 6 μM Cr(VI) for 3 h or 100 ng/ml NCS as a positive control for 30 min. After treatment, the cells were harvested and fixed with methanol. After fixation, the cells were incubated overnight with a monoclonal γ-H2AX antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) at a 1:500 dilution. The cells were then stained with goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1000 dilution), and conjugated to Alexa-488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The cells were also stained with propidium iodide (PI, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and analyzed with a FACSort flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Excitation was at 488 nm, and the emission filters used were 530 nm for Alexa-488 and 620 nm for PI. The PI fluorescence signal (fluorescence pulse-area versus pulse-width) was used to exclude doublets and aggregates from analysis [56].

3. Results

3.1. Kinetics of Cr(VI)-induced FANCD2 activation

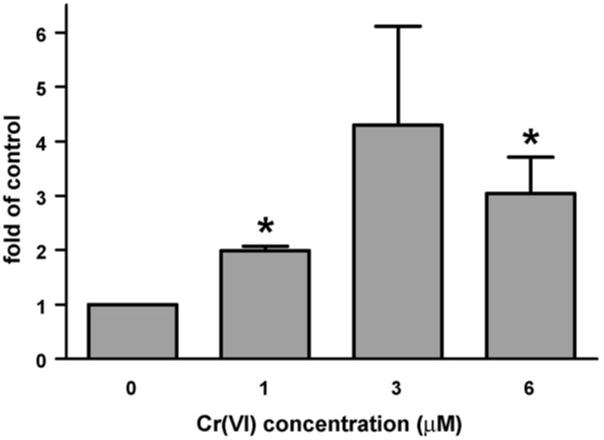

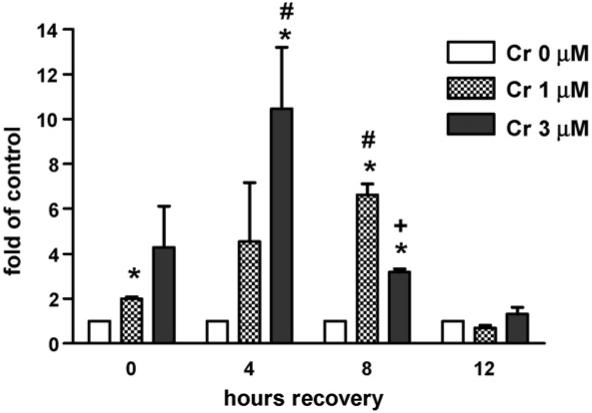

To determine if FANCD2 was activated (monoubiquitinated) by Cr(VI), normal human fibroblasts (CNTRL) were treated with 0, 1, 3, or 6 μM Cr(VI) for 24 h, followed by 0, 4, 8, or 24 h recovery periods. Total cellular extracts were immunoblotted to detect both FANCD2 isoforms. The ratio of monoubiquitinated (L) FANCD2 to unubiquitinated (S) FANCD2 was determined for each treatment and normalized to its vehicle control, i.e., in the absence of Cr(VI). Immediately after the 24 h treatment, Cr(VI) induced an increase in FANCD2 activation, which was two- and three-fold significantly higher than the control for 1 and 6 μM Cr(VI), respectively (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 2, after 1 and 3 μM Cr(VI) treatment, respective FANCD2 activation persisted (6.6- and 2.7-fold of control) until at least 8 h recovery. However, FANCD2 was de-ubiquitinated by 12 h recovery. The ratio of mono/un-ubiquitinated FANCD2 was significantly increased after 1 and 3 μM Cr(VI) exposure at 4 and 8 h post-recovery, when compared to the respective levels at 0 h post-recovery. Moreover, 1 μM Cr(VI) induced a significantly higher level of monoubiquitinated FANCD2 when compared to 3 μM Cr(VI) at 8 h post-recovery. In keeping with the requirement of FA-A in this modification, FA-A fibroblasts demonstrated no FANCD2 monoubiquitination after Cr(VI) exposure, as indicated by the total lack of an immunoreactive band corresponding to monoubiquitinated FANCD2 (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

The FA pathway is activated upon Cr(VI) treatment in normal cells. Activation (monoubiquitination) of FANCD2 in CNTRL cells after 24 h exposure to increasing concentrations of Cr(VI). CNTRL cells were exposed to 0, 1, 3, or 6 μM Na2CrO4 for 24 h. Total cellular extracts of CNTRL cells were immunoblotted to detect both FANCD2 isoforms. The ratio of monoubiquitinated FANCD2 to unubiquitinated FANCD2 was detemined for each treatment and divided by its vehicle control, i.e., in the absence of Cr(VI). Data represent the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05 by ANOVA) relative to vehicle control.

Fig. 2.

The kinetics of FANCD2 activation (monoubiquitination) in CNTRL cells after 24 h exposure to increasing concentrations of Cr(VI). CNTRL cells were exposed to 0, 1, or 3 μM Na2CrO4 for 24 h. After 24 h, the CNTRL cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated for an additional 0, 4, 8, or 24 h in complete media. Samples were analyzed for FANCD2 activation by Western blot. Data are expressed as fold of vehicle control (in the absence of Cr(VI)), and represent the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05 by ANOVA) relative to vehicle control. #Respective statistically significant difference (P < 0.05 by ANOVA) relative to 0 h post-recovery. +Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05 by ANOVA) between 1 and 3 μM Cr(VI).

3.2. Cr(VI)-induced DSB formation in both CNTRL and FA-A cells

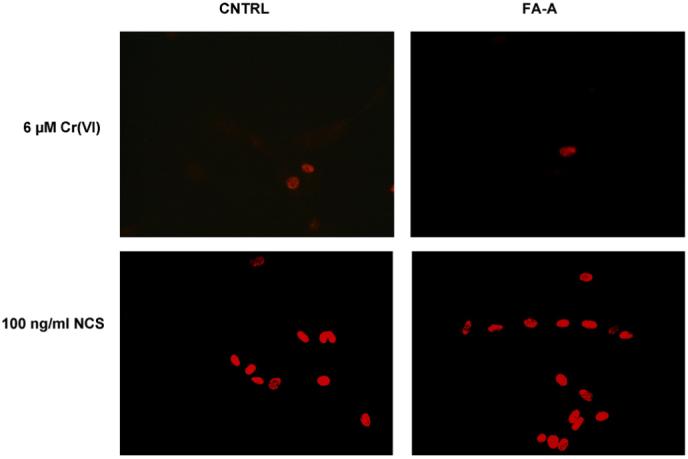

We have previously shown, in human lung fibroblasts, that Cr(VI) does not directly cause DSBs, but that DSBs are formed during S-phase, presumably as a consequence of the ICL repair [54]. To determine if the FA-A cells were deficient in the removal of the DSBs, we visualized DSBs using immunostaining with γ-H2AX. CNTRL and FA-A cells were treated with 6 μM Cr(VI) or 100 ng/ml NCS (a radiomimetic agent) for 1 h and probed with an antibody to γ-H2AX. As previously shown [54], γ-H2AX staining was observed in both Cr(VI)- and NCS-treated CNTRL and FA-A cells (Fig. 3). In both CNTRL and FA-A cells, γ-H2AX staining was restricted to a fraction of the Cr(VI)-treated cells, whereas all cells treated with NCS exhibited γ-H2AX staining. In the absence of either Cr(VI) or NCS treatment, less than 1% of cells exhibited γ-H2AX staining. These results indicate that DNA DSBs are generated to a similar extent in both CNTRL and FA-A cells after Cr(VI)-treatment.

Fig. 3.

Cr(VI) and NCS-induced γ-H2AX expression. CNTRL and FA-A cells were treated with 6 μM Cr(VI) or 100 ng/ml NCS for 1 h. The cells were fixed and incubated with an antibody against γ-H2AX. The cells were then incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated to Texas Red and viewed by fluorescence microscopy.

3.3. Cr(VI)-induced DSBs are S-phase specific

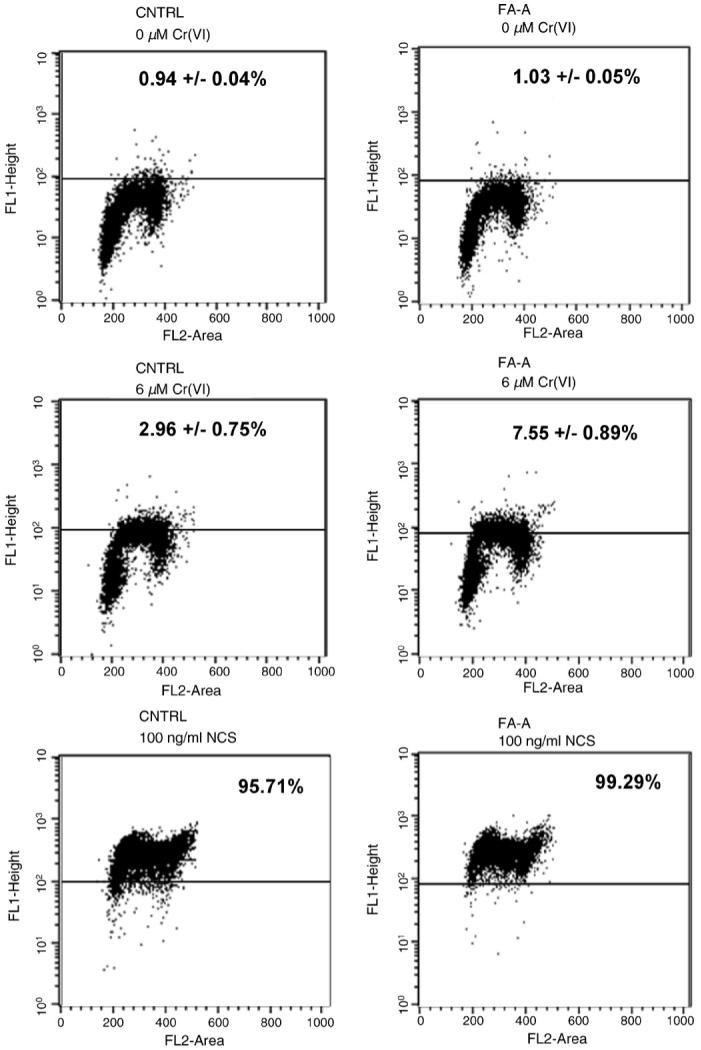

To characterize the cell cycle dependence of the Cr(VI)-induced DSBs, we studied Cr(VI)-induced γ-H2AX production by flow cytometry in the presence of PI staining. CNTRL and FA-A cells were treated with 6 μM Cr(VI) for 3 h or 100 ng/ml NCS for 30 min and were then doubly stained for γ-H2AX and PI. The dose of NCS used in this study, 100 ng/ml, was equitoxic with 6 μM Cr(VI) exposure, as analyzed by clonogenic lethality (data not shown). As indicated by PI fluorescence (Fig. 4), only S-phase CNTRL cells were γ-H2AX positive after Cr(VI) treatment, as we have previously shown [54]. Similarly, Cr(VI)-induced DSBs in FA-A cells were also restricted to the S-phase population. Exposure to 6 μM Cr(VI) induced a significant increase in S-phase-dependent γ-H2AX, which was significantly higher in the FA-A cells as compared to the control cells. In contrast, when cells were treated with 100 ng/ml NCS, γ-H2AX was equally distributed in all cell cycle phases in both CNTRL and FA-A cells.

Fig. 4.

Cr(VI)-induced S-phase specific γ-H2AX expression. CNTRL and FA-A cells were treated with 6 μM Cr(VI) for 3 h or 100 ng/ml NCS for 30 min. The cells were fixed and incubated with an antibody against γ-H2AX, followed by incubation with a secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa-488. The cells were then stained with PI and analyzed using a FACSort flow cytometer. Dot plots show γ-H2AX expression (y-axis) as an indication of DNA DSBs and PI fluorescence (x-axis) as an indication of DNA content. Numbers indicate the average ± S.E. percentage from three independent experiments of γ-H2AX positive cells after Cr(VI), and of one experiment after NCS treatment.

3.4. Cr(VI)-induced DSBs are repaired by FA-A cells

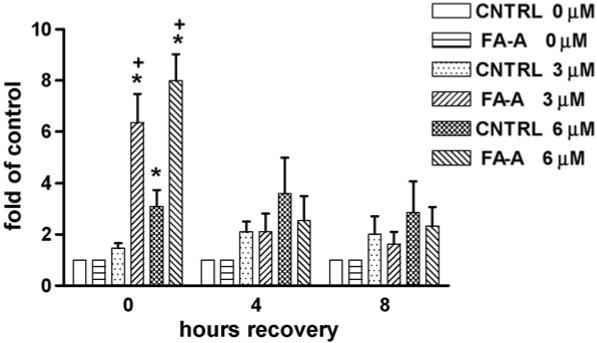

CNTRL and FA-A cells were treated with 0, 3, or 6 μM Cr(VI) for 3 h or 100 ng/ml NCS for 30 min, followed by 0, 4, or 8 h recovery periods. Flow cytometry was performed with γ-H2AX and PI double staining. Immediately after 3 and 6 μM Cr(VI) exposure, the number of γ-H2AX positive cells was 1.5- and 3.1-fold of control for CNTRL, respectively (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the respective 6.4- and 8-fold increase in γ-H2AX positive FA-A cells was significantly higher than that in CNTRL cells. The observed γ-H2AX positive cells were again restricted to S-phase during the recovery period after Cr(VI) exposure (data not shown). However, after 4 and 8 h recovery from Cr(VI) treatment, there were no longer any significant differences in γ-H2AX positive cells compared to untreated cells in either CNTRL or FA-A cells.

Fig. 5.

Repair kinetics of Cr(VI)-induced, S-phase specific DSBs. CNTRL and FA-A cells were treated with 0, 3, or 6 μM Cr(VI) for 3 h. The cells were fixed and incubated with an antibody against γ-H2AX, followed by incubation with a secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa-488. The cells were then stained with PI and analyzed using a FACSort flow cytometer. Data are expressed as fold of vehicle control, i.e., in the absence of Cr(VI), and represent the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05 by ANOVA) relative to vehicle control. +Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05 by Student’s t-test) between CNTRL and FA-A cells at equal treatment.

4. Discussion

FA cells are known to be hypersensitive to DNA crosslinking agents [2,4,8]. FANCD2 activation (monoubiquitination) has been demonstrated in response to known DNA crosslinkers, cisplatin and mitomycin C [11,24]. Photoactivated 4′-hydroxymethyl-4,5′,8-trimethylpsoralen, a potent inducer of ICLs, has also been shown to activate FANCD2 [57]. The current study provides the first molecular evidence of Cr(VI)-induced activation of the FA pathway. The monoubiquitinated FANCD2-L isoform (FANCD2-Ub) has only been observed in control or complemented FA cells that are more resistant to mitomycin C [1]. These findings indicate that the FA complex, and the subunits therein, including FA-A, are required for the conversion of FANCD2 to FANCD2-Ub. We have previously shown that FA-A cells are hypersensitive to Cr(VI) [55]. The activation of the FA pathway by Cr(VI) in CNTRL cells indicates that the FA pathway is involved in the recognition/repair of Cr(VI)-induced DNA damage, while the lack of FANCD2 monoubiquitination in FA-A cells is consistent with the requirement of FA-A in this modification [19,21-23]. Indeed, this finding is of particular significance because the clinical prognosis of FA patients is related in part to environmental factors [58,59], and Cr(VI) is an environmentally relevant genotoxin.

FA proteins localize to chromatin and the nuclear matrix following treatment with mitomycin C [60]. It has been shown that FANCD2 interacts with FANCD1/BRCA2 in a stable chromatin complex [61,62]. Monoubiquitination is required for FANCD2 association with damaged chromatin as well as for BRCA2 foci formation and chromatin complex formation [62,63]. We observed an increase in FANCD2 monoubiquitination after 24 h Cr(VI) exposure, which was somewhat enhanced during the recovery period following Cr(VI) removal. This is consistent with a recent report indicating that FANCD2 monoubiquitination corresponded with ICL repair, and increased expression of FANCD2-Ub was observed, in a time-dependent fashion, 4-24 h after removal of the crosslinking agent [57]. A recent study has shown that the de-ubiquitination enzyme, USP1, is a novel component of the FANCD2 pathway, and proposed that FANCD2 is de-ubiquitinated when cells recommence cycling after a DNA damage insult [64]. We have previously shown in dermal fibroblasts that at a concentration of 1 μM, Cr(VI) induces cell cycle arrest at predominantly G1/S and G2/M transitions, while S-phase arrest is only seen at much higher concentrations [56]. Moreover, Cr-induced growth arrest is prolonged in these cells, lasting from 8 to 10 days. Therefore, it is unlikely that de-ubiquitination is signaled by entry into the cell cycle, since these cells would still be arrested.

H2AX is a member of the histone H2A family, and is rapidly phosphorylated at serine 139 in response to ionizing radiation [65-67]. Phosphorylated H2AX is referred to as γ-H2AX. γ-H2AX is thought to be critical for recognition and repair of DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) and is required for the recruitment of the RAD50/MRE11/NBS1 complex to sites of DSBs [68-70]. We have previously shown that treatment with Cr(VI) induced DSBs, consistent with its ability to activate ATM [54,56]. Moreover, Cr(VI)-induced DSB formation was similar as assessed by both comet assay (neutral conditions) and by γ-H2AX expression. We have also shown previously, as well as in the present study, that Cr-induced DSBs are indirect and are formed only in S-phase, presumably as a consequence of the removal of the ICLs, and/or of collapsed replication forks [54]. It has been recently shown that FA cells, exposed to a potent inducer of ICLs, were fully proficient in the sensing and incision of ICLs as well as in the subsequent formation of DSBs [57]. Indeed, in the present study, we found that Cr(VI) induces S-phase-dependent DSBs in FA-A cells. Moreover, FA-A cells were several folds more sensitive to Cr-induced DSB formation, in keeping with their previously reported hypersensitivity to Cr-induced apoptosis and clonogenic lethality [55].

The FA pathway appears to be involved in homologous recombination repair (HRR) [71]. Cr(VI) is a potent inducer of recombination in mammalian cells [72]. In S. cerevisiae, members of the RAD52 epistasis group are indispensable for successful meiotic and mitotic recombination [73]. We have previously shown that rad52 yeast are hypersensitive to Cr(VI)-induced lethality, suggesting that HRR is required for processing of potentially lethal genetic lesions, and/or rescue of collapsed replication forks resulting from Cr-induced DNA damage [74,75]. This is consistent with the observed S-phase-dependent induction of DSBs by Cr(VI) in our present and previous studies [54]. Intriguingly, the FA pathway, and monoubiquitination of FANCD2, does not appear to be involved in repair of Cr(VI)-induced DSBs, as shown by the similar level of S-phase-associated γ-H2AX expression in both CNTRL and FA-A cells at 4 and 8 h after recovery from Cr(VI) treatment. Since FA-A cells were hypersensitive to Cr-induced DSB formation, the rate of repair was therefore potentially faster in these cells, compared to normal fibroblasts. The role of FA proteins and FANCD2 monoubiquitination in HRR is not completely clear [71]. FANCD2 monoubiquitination is required to promote HRR [24]. However, while FA proteins promote HRR, they are apparently not essential to the process [76]. This is in contrast to BRCA2, which is required for HRR [77]. Thus, the role of FANCD2-Ub has been proposed to facilitate BRCA2 recruitment [71]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that FANCD2 promotes a subpathway of HRR, potentially independent of rad51 [78]. A recent report has demonstrated the ability of FANCD2 to directly bind both Holliday junction DNA and double strand DNA ends; however the role of this process in DNA repair remains unclear [79]. The data in the present study is in agreement with these findings, and raises the question of the fidelity of DSB repair after Cr(VI) exposure in FA-A cells.

In summary, our data suggest that Cr(VI) activates the FA pathway and FANCD2 monoubiquitination. Moreover, the results indicate that FA cells are hypersensitive to Cr-induced S-phase-dependent DSBs, although the FA pathway does not appear to be required for DSB repair. One could speculate that the repair mechanism of Cr(VI)-induced DSBs that is active in the FA-A cells may result in incomplete or incompetent repair, related to the markedly enhanced sensitivity of these cells to Cr-induced death. These findings are particularly relevant in addressing the response of FA patients to genotoxic carcinogens known to induce FA-sensitive DNA lesions.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, NIH ES 05304 and ES 09961 (to S.R.P.)

References

- [1].D’Andrea AD, Grompe M. The Fanconi anaemia/BRCA pathway. Nat. Rev., Cancer. 2003;3:23–34. doi: 10.1038/nrc970. [Review, 120 refs] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fujiwara Y. Defective repair of mitomycin C crosslinks in Fanconi’s anemia and loss in confluent normal human and xeroderma pigmentosum cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1982;699:217–225. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(82)90110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zhen W, Evans MK, Haggerty CM, Bohr VA. Deficient gene specific repair of cisplatin-induced lesions in Xeroderma pigmen-tosum and Fanconi’s anemia cell lines. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:919–924. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.5.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rosselli F, Briot D, Pichierri P. The Fanconi anemia pathway and the DNA interstrand cross-links repair. Biochimie. 2003;85:1175–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Alter BP. Cancer in Fanconi anemia, 1927-2001. Cancer. 2003;97:425–440. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rosenberg PS, Greene MH, Alter BP. Cancer incidence in persons with Fanconi anemia. Blood. 2003;101:822–826. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Van Waes C. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in patients with Fanconi anemia. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2005;131:640–641. doi: 10.1001/archotol.131.7.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rey JP, Scott R, Muller H. Induction and removal of interstrand crosslinks in the ribosomal RNA genes of lymphoblastoid cell lines from patients with Fanconi anemia. Mutat. Res. 1993;289:171–180. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(93)90067-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Joenje H, Oostra AB, Wijker M, di Summa FM, van Berkel CG, Rooimans MA, Ebell W, van Weel M, Pronk JC, Buchwald M, Arwert F. Evidence for at least eight Fanconi anemia genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;61:940–944. doi: 10.1086/514881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Levitus M, Rooimans MA, Steltenpool J, Cool NF, Oostra AB, Mathew CG, Hoatlin ME, Waisfisz Q, Arwert F, de Winter JP, Joenje H. Heterogeneity in Fanconi anemia: evidence for 2 new genetic subtypes. Blood. 2004;103:2498–2503. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Meetei AR, de Winter JP, Medhurst AL, Wallisch M, Waisfisz Q, van de Vrugt HJ, Oostra AB, Yan Z, Ling C, Bishop CE, Hoatlin ME, Joenje H, Wang W. A novel ubiquitin ligase is deficient in Fanconi anemia. Nat. Genet. 2003;35:165–170. doi: 10.1038/ng1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Strathdee CA, Gavish H, Shannon WR, Buchwald M. Cloning of cDNAs for Fanconi’s anaemia by functional complementation. Nature. 1992;358:434. doi: 10.1038/358434a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Foe JR, Rooimans MA, Bosnoyan-Collins L, Alon N, Wijker M, Parker L, Lightfoot J, Carreau M, Callen DF, Savoia A, Cheng NC, van Berkel CG, Strunk MH, Gille JJ, Pals G, Kruyt FA, Pronk JC, Arwert F, Buchwald M, Joenje H. Expression cloning of a cDNA for the major Fanconi anaemia gene. FAA, Nat. Genet. 1996;14:488. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].de Winter JP, Leveille F, van Berkel CG, Rooimans MA, van Der WL, Steltenpool J, Demuth I, Morgan NV, Alon N, Bosnoyan-Collins L, Lightfoot J, Leegwater PA, Waisfisz Q, Komatsu K, Arwert F, Pronk JC, Mathew CG, Digweed M, Buchwald M, Joenje H. Isolation of a cDNA representing the Fanconi anemia complementation group E gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;67:1306–1308. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9297(07)62959-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].de Winter JP, Rooimans MA, van Der WL, van Berkel CG, Alon N, Bosnoyan-Collins L, de Groot J, Zhi Y, Waisfisz Q, Pronk JC, Arwert F, Mathew CG, Scheper RJ, Hoatlin ME, Buchwald M, Joenje H. The Fanconi anaemia gene FANCF encodes a novel protein with homology to ROM. Nat. Genet. 2000;24:15–16. doi: 10.1038/71626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].de Winter JP, Waisfisz Q, Rooimans MA, van Berkel CG, Bosnoyan-Collins L, Alon N, Carreau M, Bender O, Demuth I, Schindler D, Pronk JC, Arwert F, Hoehn H, Digweed M, Buchwald M, Joenje H. The Fanconi anaemia group G gene FANCG is identical with XRCC9. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:281–283. doi: 10.1038/3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Timmers C, Taniguchi T, Hejna J, Reifsteck C, Lucas L, Bruun D, Thayer M, Cox B, Olson S, D’Andrea AD, Moses R, Grompe M. Positional cloning of a novel Fanconi anemia gene, FANCD2. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:241–248. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Garcia-Higuera I, Taniguchi T, Ganesan S, Meyn MS, Timmers C, Hejna J, Grompe M, D’Andrea AD. Interaction of the Fanconi anemia proteins and BRCA1 in a common pathway. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:249–262. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Garcia-Higuera I, Kuang Y, Naf D, Wasik J, D’Andrea AD. Fanconi anemia proteins FANCA, FANCC, and FANCG/XRCC9 interact in a functional nuclear complex. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999;19:4866–4873. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].de Winter JP, van Der WL, de Groot J, Stone S, Waisfisz Q, Arwert F, Scheper RJ, Kruyt FA, Hoatlin ME, Joenje H. The Fanconi anemia protein FANCF forms a nuclear complex with FANCA, FANCC and FANCG. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:2665–2674. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.18.2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Medhurst AL, Huber PA, Waisfisz Q, de Winter JP, Mathew CG. Direct interactions of the five known Fanconi anaemia proteins suggest a common functional pathway. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:423–429. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Grompe M, D’Andrea A. Fanconi anemia and DNA repair. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2253–2259. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.20.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Waisfisz Q, de Winter JP, Kruyt FA, de Groot J, van Der WL, Dijkmans LM, Zhi Y, Arwert F, Scheper RJ, Youssoufian H, Hoatlin ME, Joenje H. A physical complex of the Fanconi anemia proteins FANCG/XRCC9 and FANCA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:10320–10325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Taniguchi T, Garcia-Higuera I, Xu B, Andreassen PR, Gregory RC, Kim ST, Lane WS, Kastan MB, D’Andrea AD. Convergence of the Fanconi anemia and ataxia telangiectasia signaling pathways. Cell. 2002;109:459–472. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00747-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Taniguchi T, Garcia-Higuera I, Andreassen PR, Gregory RC, Grompe M, D’Andrea AD. S-phase-specific interaction of the Fanconi anemia protein, FANCD2, with BRCA1 and RAD51. Blood. 2002;100:2414–2420. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].IARC . IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Vol. 49. 1990. Chromium, Nickel and Welding; pp. 1–648. [Erratum: in IARC Monogr Eval Carcinogen Risks Hum 51 (1991) 483] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Plunkett ER. Handbook of Industrial Toxicology. Chemical Publishing; New York, NY: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cassarett and Doull’s Toxicology. Maxwell-MacMillan-Pergamon; New York, NY: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ishikawa Y, Nakagawa K, Satoh Y, Kitagawa T, Sugano H, Hirano T, Tsuchiya E. “Hot spots” of chromium accumulation at bifurcations of chromate workers’ bronchi. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2342–2346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gochfeld M. Setting the research agenda for chromium risk assessment. Environ. Health Perspect. 1991;92:3–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.91923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fishbein L. Sources, transport and alterations of metal compounds: an overview. I. Arsenic, beryllium, cadmium, chromium, and nickel. Environ. Health Perspect. 1981;40:43–64. doi: 10.1289/ehp.814043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].International Agency for Research on Cancer . Monographs on the evaluation of the carcinogenic risk to humans. Vol. 49. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: 1990. Chromium, Nickel and Welding; pp. 1–648. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Leonard A, Lauwerys RR. Carcinogenicity and mutagenicity of chromium. Mutat. Res. 1980;76:227–239. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(80)90018-4. [Review, 63 refs] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Cohen MD, Kargacin B, Klein CB, Costa M. Mechanisms of chromium carcinogenicity and toxicity. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1993;23:255–281. doi: 10.3109/10408449309105012. [Review, 340 refs] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].De Flora S, Bagnasco M, Serra D, Zanacchi P. Genotoxicity of chromium compounds. A review. Mutat. Res. 1990;238:99–172. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(90)90007-x. [Review, 257 refs] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sugden KD, Martin BD. Guanine and 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine-specific oxidation in DNA by chromium(V) Environ. Health Perspect. 2002;110(Suppl 5):725–728. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s5725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sugden KD, Campo CK, Martin BD. Direct oxidation of guanine and 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine in DNA by a high-valent chromium complex: a possible mechanism for chromate genotoxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14:1315–1322. doi: 10.1021/tx010088+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Miller CA, III, Costa M. Characterization of DNA-protein complexes induced in intact cells by the carcinogen chromate. Mol. Carcinogen. 1988;1:125–133. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940010208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Standeven AM, Wetterhahn KE. Chromium (VI) toxicity: uptake, reduction, and DNA damage. J. Am. Cell. Toxicol. 1989;8:1275–1283. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Singh J, Mclean JA, Pritchard DE, Montaser A, Patierno SR. Sensitive quantitation of chromium-DNA adducts by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry with a direct injection high-efficiency nebulizer. Toxicol. Sci. 1998;46:260–265. doi: 10.1006/toxs.1998.2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Xu J, Manning FC, Patierno SR. Preferential formation and repair of chromium-induced DNA adducts and DNA-protein crosslinks in nuclear matrix DNA. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:1443–1450. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.7.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Xu J, Bubley GJ, Detrick B, Blankenship LJ, Patierno SR. Chromium(VI) treatment of normal human lung cells results in guanine-specific DNA polymerase arrest, DNA-DNA cross-links and S-phase blockade of cell cycle. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:1511–1517. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.7.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Singh J, Bridgewater LC, Patierno SR. Differential sensitivity of chromium-mediated DNA interstrand crosslinks and DNA-protein crosslinks to disruption by alkali and EDTA. Toxicol. Sci. 1998;45:72–76. doi: 10.1006/toxs.1998.2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bridgewater LC, Manning FC, Patierno SR. Base-specific arrest of in vitro DNA replication by carcinogenic chromium: relationship to DNA interstrand crosslinking. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:2421–2427. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.11.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Singh J, Carlisle DL, Pritchard DE, Patierno SR. Chromium-induced genotoxicity and apoptosis: relationship to chromium carcinogenesis (review) Oncol. Rep. 1998;5:1307–1318. doi: 10.3892/or.5.6.1307. [Review, 84 refs] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Bridgewater LC, Manning FC, Woo ES, Patierno SR. DNA polymerase arrest by adducted trivalent chromium. Mol. Carcinogen. 1994;9:122–133. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940090304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Manning FC, Xu J, Patierno SR. Transcriptional inhibition by carcinogenic chromate: relationship to DNA damage. Mol. Carcinogen. 1992;6:270–279. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940060409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Patierno SR, Banh D, Landolph JR. Transformation of C3H/10T1/2 mouse embryo cells to focus formation and anchorage independence by insoluble lead chromate but not soluble calcium chromate: relationship to mutagenesis and internalization of lead chromate particles. Cancer Res. 1988;48:5280–5288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Patierno SR, Landolph JR. Soluble vs insoluble hexavalent chromate. Relationship of mutation to in vitro transformation and particle uptake. Biol. Trace Element Res. 1989;21:469–474. doi: 10.1007/BF02917290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Zhitkovich A, Song Y, Quievryn G, Voitkun V. Non-oxidative mechanisms are responsible for the induction of mutagenesis by reduction of Cr(VI) with cysteine: role of ternary DNA adducts in Cr(III)-dependent mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 2001;40:549–560. doi: 10.1021/bi0015459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Tully DB, Collins BJ, Overstreet JD, Smith CS, Dinse GE, Mumtaz MM, Chapin RE. Effects of arsenic, cadmium, chromium, and lead on gene expression regulated by a battery of 13 different promoters in recombinant HepG2 cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2000;168:79–90. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Wetterhahn KE, Hamilton JW. Molecular basis of hexavalent chromium carcinogenicity: effect on gene expression. Sci. Total Environ. 1989;86:113–129. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(89)90199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Hamilton JW, Kaltreider RC, Bajenova OV, Ihnat MA, McCaffrey J, Turpie BW, Rowell EE, Oh J, Nemeth MJ, Pesce CA, Lariviere JP. Molecular basis for effects of carcinogenic heavy metals on inducible gene expression. Environ. Health Perspect. 1998;106(Suppl 4):1005–1015. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106s41005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ha L, Ceryak S, Patierno SR. Generation of S phase-dependent DNA double strand breaks by Cr(VI) exposure: involvement of ATM in Cr(VI) induction of {gamma}-H2AX. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:2265–2274. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Vilcheck SK, O’Brien TJ, Pritchard DE, Ha L, Ceryak S, Fornsaglio JL, Patierno SR. Fanconi anemia complementation group A cells are hypersensitive to chromium(VI)-induced toxicity. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002;110(Suppl 5):773–777. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s5773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Ha L, Ceryak S, Patierno SR. Chromium (VI) activates ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) protein: requirement of ATM for both apoptosis and recovery from terminal growth arrest. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:17885–17894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210560200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Rothfuss A, Grompe M. Repair kinetics of genomic interstrand DNA cross-links: evidence for DNA double-strand break-dependent activation of the Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:123–134. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.123-134.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Futaki M, Yamashita T, Yagasaki H, Toda T, Yabe M, Kato S, Asano S, Nakahata T. The IVS4 + 4 A to T mutation of the Fanconi anemia gene FANCC is not associated with a severe phenotype in Japanese patients. Blood. 2000;95:1493–1498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Gillio AP, Verlander PC, Batish SD, Giampietro PF, Auerbach AD. Phenotypic consequences of mutations in the Fanconi anemia FAC gene: an International Fanconi Anemia Registry study. Blood. 1997;90:105–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Qiao F, Moss A, Kupfer GM. Fanconi anemia proteins localize to chromatin and the nuclear matrix in a DNA damage- and cell cycle-regulated manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:23391–23396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Wang X, D’Andrea AD. The interplay of Fanconi anemia proteins in the DNA damage response. DNA Rep. (Amst.) 2004;3:1063–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Wang X, Andreassen PR, D’Andrea AD. Functional interaction of monoubiquitinated FANCD2 and BRCA2/FANCD1 in chromatin. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:5850–5862. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5850-5862.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Matsushita N, Kitao H, Ishiai M, Nagashima N, Hirano S, Okawa K, Ohta T, Yu DS, McHugh PJ, Hickson ID, Venkitaraman AR, Kurumizaka H, Takata M. A FancD2-monoubiquitin fusion reveals hidden functions of Fanconi anemia core complex in DNA repair. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:841–847. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Nijman SM, Huang TT, Dirac AM, Brummelkamp TR, Kerkhoven RM, D’Andrea AD, Bernards R. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP1 regulates the Fanconi anemia pathway. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Thatcher TH, Gorovsky MA. Phylogenetic analysis of the core histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:174–179. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.2.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].West MH, Bonner WM. Histone 2A, a heteromorphous family of eight protein species. Biochemistry. 1980;19:3238–3245. doi: 10.1021/bi00555a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Rogakou EP, Pilch DR, Orr AH, Ivanova VS, Bonner WM. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:5858–5868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Celeste A, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Kruhlak MJ, Pilch DR, Staudt DW, Lee A, Bonner RF, Bonner WM, Nussenzweig A. Histone H2AX phosphorylation is dispensable for the initial recognition of DNA breaks. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:675–679. doi: 10.1038/ncb1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Furuta T, Takemura H, Liao ZY, Aune GJ, Redon C, Sedelnikova OA, Pilch DR, Rogakou EP, Celeste A, Chen HT, Nussenzweig A, Aladjem MI, Bonner WM, Pommier Y. Phosphorylation of histone H2AX and activation of Mre11, Rad50, and Nbs1 in response to replication-dependent DNA double-strand breaks induced by mammalian DNA topoisomerase I cleavage complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:20303–20312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Paull TT, Rogakou EP, Yamazaki V, Kirchgessner CU, Gellert M, Bonner WM. A critical role for histone H2AX in recruitment of repair factors to nuclear foci after DNA damage. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:886–895. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00610-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Thompson LH, Hinz JM, Yamada NA, Jones NJ. How Fanconi anemia proteins promote the four Rs: replication, recombination, repair, and recovery. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2005;45:128–142. doi: 10.1002/em.20109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Helleday T, Nilsson R, Jenssen D. Arsenic[III] and heavy metal ions induce intrachromosomal homologous recombination in the hprt gene of V79 Chinese hamster cells. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2000;35:114–122. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2280(2000)35:2<114::aid-em6>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Sung P, Trujillo KM, Van Komen S. Recombination factors of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. 2000;451:257–275. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].O’Brien TJ, Fornsaglio JL, Ceryak S, Patierno SR. Effects of hexavalent chromium on the survival and cell cycle distribution of DNA repair-deficient S. cerevisiae. DNA Rep. 2002;1:617–627. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].O’Brien TJ, Ceryak S, Patierno SR. Complexities of chromium carcinogenesis: role of cellular response, repair and recovery mechanisms. Mutat. Res. 2003;533:3–36. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Nakanishi K, Yang YG, Pierce AJ, Taniguchi T, Digweed M, D’Andrea AD, Wang ZQ, Jasin M. Human Fanconi anemia monoubiquitination pathway promotes homologous DNA repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:1110–1115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407796102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Moynahan ME, Pierce AJ, Jasin M. BRCA2 is required for homology-directed repair of chromosomal breaks. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:263–272. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Yamamoto K, Hirano S, Ishiai M, Morishima K, Kitao H, Namikoshi K, Kimura M, Matsushita N, Arakawa H, Buer-stedde JM, Komatsu K, Thompson LH, Takata M. Fanconi anemia protein FANCD2 promotes immunoglobulin gene conversion and DNA repair through a mechanism related to homologous recombination. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:34–43. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.34-43.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Park WH, Margossian S, Horwitz AA, Simons AM, D’Andrea AD, Parvin JD. Direct DNA binding activity of the Fanconi anemia D2 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:23593–23598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503730200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]