Abstract

Aim

To assess the effectiveness of the long-term group psychotherapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in war veterans on the basis of clinical picture of PTSD, associated neurotic symptoms, and adopted models of psychological defense mechanisms.

Methods

Prospective cohort study involved 59 war veterans who participated in dynamic-oriented supportive group psychotherapy for five years. The groups met once a week for 90 minutes. Forty-two veterans finished the program. The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale structured interview was used to assess the intensity of PTSD. Crown-Crisp Index was used to evaluate other neurotic symptoms, and Life Style Questionnaire was used to assess the defense mechanisms. The assessments were done at the beginning of psychotherapy, after the second, and after the fifth year of treatment. Comorbid diagnoses, hospitalizations, and outpatient clinic treatments were also recorded.

Results

Long-term group psychotherapy reduced the intensity of PTSD symptoms in our patients (the difference between Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale score at the beginning and the end of treatment, F = 9.103, P = 0.001). Other neurotic symptoms and the characteristic profile of defense mechanisms did not change significantly during the course of treatment. Predominant defense mechanisms were projection (M = 82.0 ± 14.4) and displacement (M = 69.0 ± 16.8). None of the symptoms or defense mechanisms present at the beginning of the treatment changed significantly after two or five years of treatment. The number of diagnosed major depressive episodes, which increased after the second year of psychotherapy, decreased by the end of treatment.

Conclusion

Psychotherapy can reduce the intensity of PTSD symptoms, but the changes in the personality of veterans with PTSD are deeply rooted. Traumatic experiences lead to the formation of rigid defense mechanisms, which cannot be significantly changed by long-term group psychotherapy.

A traumatic experience greatly changes the perception of inner and outer world in a patient with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (1). Feelings of deep isolation, alienation, helplessness, and distrust, together with interpersonal problems and socially dysfunctional behavior, are the main psychological components of PTSD (1). Group psychotherapy, therefore, has the central role in the integrated psychiatric treatment of patients with PTSD (2).

Since 1980, when the term “posttraumatic stress disorder” was introduced in psychiatric nomenclature, numerous studies have been conducted to establish the most appropriate psychotherapeutic methods for treating this disorder (3). Although recent guidelines recommend cognitive-behavioral approach, it seems that this type of therapy cannot be successfully applied in all war veterans, especially not in those with chronic PTSD (2-5). Deeply rooted changes in personality, which disturb biological, psychological, and social equilibrium, require long-term therapy. The corrective emotional experience and the feeling of security in a therapeutic group setting strengthen the healthy parts of the self, and neutralize and reintegrate the destructive ones (6). Dynamic-oriented group therapy is commonly used because the number of patients who need psychological help is relatively high, the availability of group therapists is limited, and the range of indications for this type of therapy is broad (2).

After the 1991-1995 war in Croatia, the number of war veterans asking for psychiatric help has been increasing. In the first encounters with these patients, psychiatrists prescribed psychopharmaceuticals more often than short psychotherapeutic interventions. However, they soon realized that PTSD symptoms were recurring after an initial improvement and that the disorder had a strong and lasting impact on the patients' professional, social, and family life. It was obvious that initially applied treatment methods could not successfully meet veterans’ needs for continuous and accessible mental health care. A more comprehensive and effective psychotherapeutic approach had to be adopted (6,7).

Our aim was to assess the effectiveness of long-term group psychotherapy in the treatment of war veterans with PTSD by evaluating the clinical picture of PTSD, associated neurotic symptoms, and adopted models of psychological defense mechanisms after two and five years of treatment.

Participants and methods

Participants

All war veterans who sought outpatient psychotherapy treatment at the Psychiatric Department of Split University Hospital between April and December 1997 were eligible for the study. A detailed screening procedure was performed to identify the veterans with PTSD, as defined in the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (8). For this purpose, clinical interview and patients’ medical records were used, including the findings of a psychiatrist and a psychologist and intelligence test results. Veterans aged between 25 and 60 years and diagnosed with PTSD, which occurred due to traumatic experiences during their service in the Croatian Army, were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were central nervous system disease, alcoholism, drug addiction, acute psychosis, and below-average intelligence. Data on participants' intelligence were obtained from their medical records.

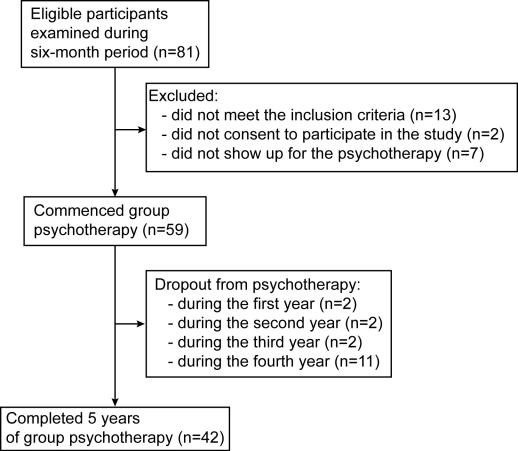

We examined a total of 81 war veterans (Figure 1). Thirteen of them did not meet the inclusion criteria: the diagnosis of PTSD was not confirmed in 5 veterans, one veteran was a drug addict, 3 had acute psychosis, 2 were older than 60 years, and 2 had below-average intelligence. Two veterans refused to participate and 7 never came to group psychotherapy.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study participants.

Fifty-nine veterans with PTSD began the psychotherapy treatment. All were men with a mean age (±standard deviation) of 43.0 ± 7.1 years; most of them were in the 35-40 age group. Majority (n = 34) had high school education (10-12 years of school). Two-thirds were married and almost half of them had 3-4 years of war experience (Table 1). Eight veterans had traumatic experiences in childhood (victims of child abuse or experienced a life-threatening situation) and 2 had a traumatic experience after the war (death of a child).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of 59 war veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder who started five-year group psychotherapy program at the Split University Hospital, Croatia

| No. of

veterans in group psychotherapy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | completed 5-y program (n = 42) | dropped out (n = 17) | P (χ2 test) |

| Age group (y): | |||

| 30-35 | 6 | 4 | 0.103 |

| 35-40 | 15 | 2 | |

| 40-45 | 7 | 7 | |

| 45-50 | 10 | 4 | |

| >50 | 4 | 0 | |

| Education: | |||

| primary school | 4 | 3 | 0.912 |

| high school | 34 | 13 | |

| university | 4 | 1 | |

| Marital status: | |||

| married | 28 | 11 | 0.960 |

| single | 11 | 5 | |

| divorced | 3 | 1 | |

| Duration of the war experience (y): | |||

| <3 | 11 | 11 | 0.016 |

| 3-4 | 20 | 5 | |

| >4 | 11 | 1 | |

All veterans gave their oral informed consent to participate in the study. Forty-two veterans completed the whole course of 5-year treatment, whereas 17 quit psychotherapy at different phases of the treatment, mostly during the fourth year (Figure 1).

The veterans who finished the treatment and those who dropped out did not differ significantly in their demographic characteristics. However, a significant difference was found in the duration of their war experience, with those having longer combat experience staying in the program (Table 1).

Group psychotherapy

We used homogenous, long-term psychodynamically-oriented supportive group psychotherapy (1). The veterans were divided into seven semi-open groups, three with 9 participants each and four with 8 participants each. The groups met once a week for 90 minutes. The sessions were conducted by three psychiatrists and a psychologist educated in group psychotherapy and experienced in working with war veterans.

The goal of our psychotherapeutic work was to relieve the symptoms, help veterans to develop more mature adaptation mechanisms, and stimulate the reparation of discontinued and fragmented self to support personality integration and reintegration of the veterans into family and society (1).

Therapists aimed to establish trust, security, and reciprocity in the group and to stimulate the development of group therapeutic factors – psychoeducation, universality, hope, altruism, acceptance, self-discovering, disclosure of the traumatic experience, and interpersonal learning. Techniques that were used in the group combined the supportive and dynamic approach (1).

Although it was difficult to distinguish clearly between particular phases of the group work, three basic phases in the development of these groups could be recognized.

First phase. At the beginning of the group psychotherapy, the main goal was to establish basic security and trust in both the group and the therapist. This phase lasted between one and two years. The emphasis was put on supportive and psychoeducational techniques. The group sessions were conducted in an active, facilitating, and stimulating way, focusing on healthy parts of the personality. Interventions aimed at fostering these processes combined “pragmatic” and “here-and-now” approach. The level of confrontation was low to medium. The most frequent conversation topics in the group were PTSD symptoms and their significance in the everyday life, the problems of social reintegration, and dissatisfaction with the current reception of veterans in the society.

Second phase. During this phase, which lasted approximately from the middle of the second until the end of the fourth year, a higher level of group cohesion was achieved. Mutual trust and closeness increased. In this phase, the supportive approach was partly retained, but the emphasis was on psychodynamic techniques. Therapists encouraged group members to recall the traumatic experiences as accurately as possible and discover their affective meaning. The emphasis was put on the integration of the experiences within self by putting them into the context of pre- and posttraumatic events. Disclosure of traumatic experiences, associated with feelings of guilt and other emotions, threatened the previously achieved inner equilibrium.

Third phase. In the last phase of the group development (the fifth year), the goal was to work through newly formed concepts and integrate them within the self. These concepts provided a fresh view of the traumatic event and affirmation of the patient's adaptive capacity. This capacity depended on the pre-traumatic personality structure and the existent social support. In this phase, the role of the therapist was to stimulate the adoption of more mature adaptive patterns and encourage an active involvement of veterans into the community. Main topics of interest in the group discussions were related to family issues. Veterans were increasingly optimistic and they felt the need to make their time meaningful and creative.

Methods

We used a structured interview to collect the data on demographic characteristics, traumatic experiences in childhood, traumatic experiences during group psychotherapy treatment, comorbid diagnoses, and hospital and outpatient treatment.

The symptoms in veterans were assessed by a psychiatrist who led one of the groups, using Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (9), and by a psychologist using Crown-Crisp Experiential Index (10) and Life Style Questionnaire (11). There were 59 veterans evaluated at the beginning, 55 after two, and 42 after five years of psychotherapy.

Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale is a structured clinical interview that targets diagnostic criteria for PTSD outlined in the Fourth Edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; ref. 9). Each symptom is presented as a sum of its intensity and frequency in the last month. The Scale has good metric characteristics, high reliability and good validity, in comparison to other instruments, which makes it the method of choice for the assessment of PTSD (9,12).

Crown Crisp Experiential Index is used to assess neurotic symptoms and measure changes after a certain intervention (11). It is an objective instrument, which satisfactorily meets two basic psychometric criteria: reliability and validity.

Life Style Questionnaire and Defense Mechanisms was adapted from the Life Style Index (13). It is based on Plutchnik's theory of eight primary emotions and eight basic defense mechanisms, which are crucial for keeping those emotions under control. The Life Style Questionnaire and Defense Mechanisms meet the criteria of required reliability and validity (13).

Statistical analysis

Variables were evaluated descriptively (mean±standard deviation) and dependent samples were analyzed with repeated measures ANOVA and t test. Differences between pairs of measurements (the first and the second, the first and the third, and the second and the third) were calculated with t test, whereas differences between demographic characteristics of veterans who completed the therapy and those who dropped out were assessed with χ2 test. SPSS statistical software, version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The level of significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

The most prevalent lifetime comorbid diagnoses were personality disorder, diagnosed in 6 veterans, and alcohol abuse, diagnosed in 5 veterans. Comorbid disorders were assessed for a six-month period before the interview. In that period, 4 participants were hospitalized and 7 were treated in the psychiatric outpatient clinic. After two years of psychotherapy, 13 participants needed in-hospital treatment. Four of them developed major depressive disorder and 3 had problems with drug abuse. The veterans who quit the group psychotherapy spent less then three years on the front line than those who finished the therapy (Table 1). In the last phase of psychotherapy, none of the participants had major depressive disorder, one had problems with alcohol, one with illegal drugs abuse, and 2 received in-hospital treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comorbid psychiatric disorders and hospitalizations of 42 war veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder who completed five-year group psychotherapy program at the Split University Hospital, Croatia

| No. of veterans | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| psychotherapy |

||||

| Disorder | before the war | at the beginning | after 2 y | after 5 y |

| Major depressive disorder | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Suicide attempt | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Anxiety disorder | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Personality disorder | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Abuse of alcohol | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Abuse of illegal drugs | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Psychotic disorder | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| No. of hospitalized patients | 0 | 4 | 13 | 2 |

| No. of patients treated in a day hospital | 0 | 7 | 16 | 3 |

| Total | 15 | 27 | 52 | 15 |

Symptoms of PTSD according to DSM-IV criteria

The symptoms of reenactment of traumatic experience, as defined in the group B of DSM-IV criteria, were most pronounced after the second year of psychotherapy and least pronounced at the end of the treatment (Table 3). The symptoms listed in the group B of DSM-IV criteria and scores B at the beginning of the treatment were significantly different from those after two and five years of treatment. Score B was significantly lower after five years of psychotherapy than at the beginning or after two years of treatment.

Table 3.

Changes in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in 42 war veterans who underwent five-year group psychotherapy program at the Split University Hospital, Croatia

| CAPS*

score (mean±SD) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| psychotherapy |

||||

| Symptom† | baseline | after 2 y | after 5 y | P |

| B1 – intrusive recollections | 5.9 ± 1.7 | 6.1 ± 1.4 | 4.0 ± 2.5‡ | <0.001 |

| B2 – distressing dreams | 5.6 ± 2.0 | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 3.7 ± 2.9‡ | <0.001 |

| B3 – acting or feeling as if event were recurring | 3.7 ± 2.3 | 4.0 ± 2.0 | 2.1 ± 1.9‡ | <0.001 |

| B4 – psychological distress at exposure to cues | 4.3 ± 2.4 | 4.3 ± 2.0 | 2.8 ± 2.2‡ | <0.001 |

| B5 – physiological reactivity on exposure to cues | 4.1 ± 2.4 | 4.0 ± 2.0 | 2.7 ± 2.2‡ | <0.001 |

| B score | 23.7 ± 8.3 | 24.4 ± 6.1 | 15.3 ± 9.2‡ | <0.001 |

| C6 – avoidance of thoughts or feelings | 4.1 ± 2.7 | 4.3 ± 2.5 | 4.5 ± 2.1 | 0.736 |

| C7 – avoidance of activities, places or people | 4.0 ± 2.6 | 3.8 ± 2.4 | 3.7 ± 2.3 | 0.649 |

| C8 – inability to recall important aspect of trauma | 1.4 ± 2.0 | 1.5 ± 2.0 | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 0.305 |

| C9 – diminished interest in activities | 5.6 ± 2.2 | 5.3 ± 2.0 | 4.7 ± 2.0 | 0.069 |

| C10 – detachment or estrangement | 4.7 ± 2.4 | 4.6 ± 2.0 | 4.4 ± 2.0 | 0.741 |

| C11 – restricted range of affect | 3.6 ± 2.8 | 3.5 ± 2.7 | 3.0 ± 2.5 | 0.299 |

| C12- – sense of foreshortened future | 4.3 ± 2.6 | 3.9 ± 2.4 | 4.3 ± 2.1 | 0.048 |

| C score | 27.8 ± 10.8 | 27.0 ± 9.5 | 26.3 ± 10.2 | 0.464 |

| D13 – difficulty falling or staying asleep | 5.8 ± 2.1 | 5.8 ± 1.6 | 4.2 ± 2.4 | 0.002 |

| D14 – irritability or outbursts of anger | 5.7 ± 2.1 | 5.5 ± 2.2 | 4.3 ± 1.9 | 0.005 |

| D15 – difficulty concentrating | 5.1 ± 2.2 | 5.1 ± 2.5 | 4.1 ± 2.3 | 0.035 |

| D16 – hypervigilance | 4.1 ± 2.8 | 3.7 ± 2.8 | 3.5 ± 2.8 | 0.048 |

| D17 – exaggerated startle response | 3.1 ± 2.7 | 3.0 ± 2.6 | 2.4 ± 2.2 | 0.201 |

| D score | 23.4 ± 9.1 | 23.6 ± 8.1 | 18.4 ± 8.4 | 0.001 |

| Total score | 74.6 ± 21.7 | 74.8 ± 18.4 | 60.2 ± 21.8‡ | 0.001 |

*CAPS – Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; PTSD – posttraumatic stress disorder.

†According to the Fourth Edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (9).

‡Significantly different from both the baseline values and values after 2 years (repeated measures ANOVA, post hoc t test for dependent samples with Bonferroni's correction).

In the group C of the criteria, which includes symptoms of avoidance and emotional rigidity, six out of seven symptoms did not significantly change after two and five years of psychotherapy (Table 3). The intensity of symptom C9 (diminished interest in important activities) significantly changed after two and five years of psychotherapy. The value of the symptom C9 was significantly lower at the beginning of treatment than after two and five years of psychotherapy. This difference was not found after Bonferroni correction was applied (Table 3).

The intensity of some symptoms in the group D of the criteria, characterized by increased excitation, was significantly reduced at the end of treatment (Table 3). Difficulties in falling or staying asleep (D13), irritability or outbursts of anger (D14), difficulties with concentration (D15), and hypervigilance (D16) significantly changed after two and five years of psychotherapy. The last symptom, exaggerated startle response, had lower value at the end of the treatment, but the observed difference was not statistically significant.

Mean total sum of symptoms from the group D of the criteria was significantly different after two and five years of psychotherapy (Table 3). The total D score was lower after five years of psychotherapy than at the beginning or after two years of treatment, but the difference was not significant after Bonferroni’s correction was applied.

The total Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale score was significantly lower at the end of treatment than at the beginning or after two years of psychotherapy (Table 3).

Other neurotic symptoms

Scores on anxiety, phobia, somatization, and depression scales were high at the beginning and after the second and fifth year of group psychotherapy. Obsession and hysteria scores were normal at the beginning of treatment, two years later, and at the end of treatment (Table 4). Neither of these scales showed statistical difference in the intensity at the three assessment periods.

Table 4.

Changes in neurotic symptoms of 42 war veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder who completed five-year group psychotherapy program at the Split University Hospital, Croatia

| Crown-Crisp Experiential Index Score (mean±SD) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| psychotherapy | ||||

| Neurotic symptoms | baseline | after 2 y | after 5 y | P |

| Anxiety | 13.0 ± 2.0 | 12.8 ± 1.7 | 12.48 ± 2.6 | 0.178 |

| Phobic | 8.6 ± 3.5 | 8.4 ± 3.2 | 8.1 ± 3.1 | 0.493 |

| Obsession | 9.8 ± 2.8 | 9.5 ± 2.6 | 9.4 ± 2.5 | 0.483 |

| Somatization | 13.1 ± 2.7 | 13.0 ± 2.7 | 12.5 ± 3.3 | 0.398 |

| Depression | 11.5 ± 2.5 | 11.6 ± 2.7 | 11.0 ± 3.3 | 0.620 |

| Hysterias | 3.2 ± 2.6 | 4.1 ± 2.4 | 3.5 ± 2.3 | 0.228 |

Defense mechanisms

At the very beginning of the psychotherapeutic treatment, projection and displacement were predominant defense mechanisms. After the long-term group psychotherapy, there were no major changes in these mechanisms. The results obtained at the self-assessment interview confirmed our observations.

The predominant defense mechanism at the beginning of the study was projection (M = 82.0 ± 14.4). Projection scores remained almost unchanged after two and five years of psychotherapy (Table 5). The second defense mechanism was displacement, which was present at the beginning of the treatment almost as much (M = 69.0 ± 16.8) as two years later (M = 68.6 ± 15.2). Although its intensity at the end of treatment was somewhat lower (M = 65.7 ± 10.0), the difference was not statistically significant. Regression and intellectualization were used almost equally at the beginning and at the end of the treatment. The mean regression score was M = 58.9 ± 11.0 at the beginning, M = 56.5 ± 11.7 after two years, and M = 56.1 ± 14.8 at the end of the treatment. Although there was a difference between the regression scores, it was not statistically significant (Table 5). Intellectualization was used less often at the end of treatment, but not significantly (Table 5). The least often used defense mechanisms at all three assessments were compensation and negation.

Table 5.

Changes in defense mechanisms in 42 war veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder who completed five-year group psychotherapy program at the Split University Hospital, Croatia

| Life

Style Questionnaire. Score (mean±SD) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| psychotherapy |

||||

| Defense mechanisms | baseline | after 2 y | after 5 y | P |

| Reactive formation | 50.0 ± 20.1 | 50.0 ± 10.0 | 48.5 ± 19.8 | 0.840 |

| Denial | 37.4 ± 16.1 | 36.7 ± 16.4 | 38.5 ± 19.3 | 0.811 |

| Regression | 58.9 ± 11.0 | 56.5 ± 11.7 | 56.1 ± 14.8 | 0.328 |

| Repression | 54.8 ± 17.6 | 50.6 ± 18.1 | 46.4 ± 20.9 | 0.070 |

| Compensation | 28.2 ± 18.1 | 28.6 ± 17.7 | 27.1 ± 16.1 | 0.817 |

| Projection | 82.1 ± 14.4 | 80.5 ± 13.4 | 80.1 ± 15.3 | 0.759 |

| Intellectualization | 56.4 ± 19.2 | 54.7 ± 19.0 | 52.5 ± 20.2 | 0.449 |

| Displacement | 69.0 ± 16.8 | 68.6 ± 15.2 | 65.7 ± 10.0 | 0.551 |

Discussion

Our study showed that long-term group psychotherapy led to a reduction in symptoms of PTSD in war veterans, whereas other neurotic symptoms and the characteristic profile of defense mechanisms remained unchanged.

The limitations of the study were a small sample size and high dropout rate. The design of study did not allow us to assess therapeutic effects of group psychotherapy on each individual participant or have an insight into the details of group dynamics. Furthermore, the groups were led by different psychotherapists, which could cause differences between the groups in group dynamics and consequently compromise the homogeneity of applied therapeutic technique. However, if we were to remove this shortcoming by assessing the effects of the group psychotherapy performed by a single psychotherapist, the number of included participants would be even smaller. There was also a problem of having no control group, a frequent problem in psychotherapy, since it is very difficult to find a group that would match the patients in all relevant characteristics.

There were patients who received psychopharmacological treatment during group therapy and were hospitalized for 1 day to 2 months, some more than once. This poses the question of a possible influence of medications and hospital treatment on the improvement of clinical picture of PTSD. These problems were described in other studies investigating the effects of psychotherapy in traumatized patients (14).

We could not identify studies similar to this one. Most of the studies were descriptive reports on group functioning with an emphasis on the group dynamics (14). However, the literature provides detailed descriptions of how supportive or psychodynamic homogenous psychotherapeutic groups work (3,5,15-18).

The results we obtained were different at different assessment periods. Deterioration in the clinical picture after the second year of psychotherapy may be related to the functioning of the groups. During the second year of psychotherapy, patients’ trust in the group and closeness among the group members increased. Emotional climate of security and confidence created in this way stimulates and catalyzes the disclosure of traumatic events and evokes the feelings of guilt and shame. Facing disturbing memories and related destructive feelings disrupts the already established intrapsychic equilibrium. In these critical moments of psychotherapeutic process, psychiatric hospitalization has a beneficial effect. In the final year of treatment, the number of hospitalizations among veterans included in our study considerably decreased: only two were hospitalized.

Research has shown that all symptoms in cases of very disturbing PTSD images persist for a long time, whereas symptoms of intrusion, avoidance, and emotional numbness in cases of less disturbing PTSD images decrease (19). Therefore, it is not clear whether improvements in the clinical picture result from the treatment or are part of the “natural course of the disorder.”

Although we observed beneficial effects of group psychotherapy on reducing anxiety and depression, the results of self-evaluation scales showed no change in the levels of these neurotic symptoms, which were high from the beginning. Despite the high scores on the anxiety and depression scale, the diagnosis of major depressive disorder was relatively rare. High levels of anxiety and depression are in accordance with the published literature (20,21), but it may be possible that sensitivity of the applied diagnostic instrument was not high enough. This indicates the importance of parallel use of other instruments for assessing anxiety and depression. Also, the relative ineffectiveness of psychotherapy in the treatment of neurotic symptoms and their aggravation may be a consequence of the veterans’ wish to obtain secondary gain, ie, to retain their pension and disability status, which was subject to revisions at that time (22). Changes in the regulations on veterans’ rights and the complex process of acquiring pension and disability status can provoke a retraumatization in veterans, which may also be responsible for the observed lack of improvement.

In the beginning of the therapy, we noticed that our groups of veterans were very regressive, which was also shown by other authors (6). The predominant defense mechanisms were the most immature mechanisms: projection, displacement, and regression. The mature mechanism of compensation was least dominant.

Immature mechanisms protect traumatized person's ego from regressive and autistic parts of personality activated by a traumatic event. By projection, threatening and frightening objects are kept outside self. Besides regression and projection, frequent defense mechanisms are splitting, idealization, undoing, and projective identification, but these were not the subject of our investigation (23,24).

We could not use more elaborate instruments for assessment of defense mechanisms, such as Defense Style Questionnaire, because they have not been used and validated for Croatian population. A study evaluating 7 different methods for assessing the defense functioning, including Life Style Questionnaire and Defense Mechanisms, did not find a single instrument superior to others that could serve as the “gold standard” (25).

Low level of compensation indicates the inability to complete the process of mourning for the lost good object. Although the control over regressive and bad parts of self is established, good inner objects do not yet seem to be satisfactory restituted and reintegrated, and self-esteem is not increased. High levels of anxiety, phobia, and depression, which remained unchanged during therapy in veterans in our study, support this observation.

One of the reasons for the psychotherapy’s inadequate success in adopting the mature defense mechanisms is the negative influence of group homogeneity factor, which increases members’ dependence on the group (6). In this way, the group becomes and remains a transitional object toward the outer world. Instead of resolving members’ dependence on the group, long-term psychotherapy often maintains it by inhibiting the use of the mature defense mechanisms.

Future studies should focus on increasing the efficacy of this psychotherapeutic technique by using valid and comprehensive assessment instruments and by comparing its efficacy with that of other techniques used in the same groups of patients.

Our study showed that changes in the personality of veterans with PTSD were deeply rooted and that traumatic experiences leading to a formation of a rigid model of defense functioning cannot be easily influenced by group psychotherapy. However, this method can reduce the intensity of PTSD symptoms and thus increase the veterans’ quality of life and improve their adaptation to family and society. The most important effect of the group psychotherapy is the improvement in the functioning of the social self. Therefore, we can say that group psychotherapy plays an important role in the integral approach of the treatment of chronic PTSD.

References

- 1.Willson JP, Friedman MJ, Lindy JD, editors. Treating psychological trauma and PTSD. New York, London: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marmar CR. An Integrated approach for treating posttraumatic stress. In: Pynoos RS, editor. Posttraumatic stress disorder. A clinical review. Lutherville: The Sidran Press; 1994. p. 99-132. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shalev AY, Bonne O, Eth S. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a review. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:165–82. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199603000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon SD, Johnson DM. Psychosocial treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a practice-friendly review of outcome research. J Clin Psychol. 2002;58:947–59. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.PTSD Treatment Guidelines Task Force Guidelines for treatment of PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13:539–88. doi: 10.1023/A:1007802031411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gregurek R. Countertransference problems in the treatment of a mixed group of war veterans and female partners of war veterans. Croat Med J. 1999;40:493–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kozaric-Kovacic D, Kocijan-Hercigonja D, Jambrosic A. Psychiatric help to psychotraumatized persons during and after war in Croatia. Croat Med J. 2002;43:221–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. The ICD 10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Clinical Descriptions and the Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneve: WHO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. fourth ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crown S, Crisp AH. Manual of the Crown-Crisp Experiential Index. London: Hodder and Stoughton; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamovec T, Bele-Potočnik Ž, Boben D. Revised Questionnaire of Life Style and Defense Mechanisms (according to Kellerman) [in Slovenian]. Ljubljana: Produktivnost, Centar za psihodiagnostička sredstva; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henigsberg N, Folnegovic-Smalc V, Moro Lj. Stressor characteristics and post-traumatic stress disorder symptom dimensions in war victims. Croat Med J. 2001;42:543–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plutchik R. A general psychoevolutionary theory of emotion. In: Plutchik R, Kellerman H, editors. Emotions: theory, research and experience. Vol. 1. Theories of emotion. New York (NY): Academic Press; 1980. p. 3-33. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koller P, Marmar CR, Kanas N. Psychodynamic group treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. Int J Group Psychother. 1992;42:225–46. doi: 10.1080/00207284.1992.11490687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munley PH, Bains DS, Frazee J, Schwartz LT. Inpatient PTSD treatment: a study of pretreatment measures, treatment dropout, and therapist ratings of response to treatment. J Trauma Stress. 1994;7:319–25. doi: 10.1007/BF02102952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scurfield R, Kenderdine S, Pollard R. Inpatient treatment for war-related post-traumatic stress disorder: initial findings on a longer-term outcome study. J Trauma Stress. 1990;3:185–202. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson DR, Rosenheck R, Fontana A, Lubin H, Charney D, Southwick S. Outcome of intensive inpatient treatment for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:771–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Foy DW, Shea MT, Hsieh FY, Lavori PW, et al. Randomized trial of trauma-focused group therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: results from a Department of Veterans affairs cooperative study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:481–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McFarlane AC, Yehuda R. Resilience, vulnerability, and the course of posttraumatic reactions. In: Van der Kolk BA, Mc Farlane AC, Weisaeth L, editors. Traumatic stress: effects of overwhelming experience on mind, body and society. New York, London: Guilford Press; 1996. p. 155-81. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozaric-Kovacic D, Hercigonja DK, Grubisic-Ilic M. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in soldiers with combat experiences. Croat Med J. 2001;42:165–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brady KT, Killeen TK, Brewerton T, Lucerini S. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(Suppl 7):22–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kozaric-Kovacic D, Bajs M, Vidosic S, Matic A, Alegic Karin A, Peraica T. Change of diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder related to compensation-seeking. Croat Med J. 2004;45:427–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Punamaki RL, Kanninen K, Qouta S, El-Sarraj E. The role of psychological defenses in moderating between trauma and post-traumatic symptoms among Palestinian men. Int J Psychol. 2002;37:286–96. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emery PE, Emery OB. The defense process in posttraumatic stress disorders. Am J Psychother. 1985;39:541–52. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1985.39.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guldberg CA, Hoglend P, Perry JC. Scientific methods for assessing psychological defenses. Nord J Psychiatry. 1993;47:435–46. [Google Scholar]