Abstract

We investigated the circumstances of building of the Civic Hospital in Split in the light of new archival evidence. The study necessitated a thorough review of the older historiography and previously unpublished archival sources kept in the State Archives in Venice and Zadar. The findings showed that construction of the hospital building finished in 1797, ie, five years later than officially cited. The topographical plan and the original project of the Split Civic Hospital were found, as well as the name of the project's author and the building supervisor. The data on the earliest efforts of Ergovac brothers to acquire land and building permission were corrected. The study revealed a recognizable pattern in the attitude of the authorities toward the establishment of a hospital at the end of 18th century.

The first mention of hospitals in Split (Spalato) can be traced back to the Middle Ages. These early establishments were shelters for the poor, aged, and disabled, rather than medical institutions in the modern sense of the word. Most of them were situated outside the city walls (1,2).

There have been a few comprehensive studies into the development of earliest medical institutions. The most recent one investigated the history of the church, confraternity, and hospital of Santo Spirito in Split from its beginnings to the 17th century, when the hospital was used as an institution for medical care of the Venetian military (3).

The hospital Santo Spirito in Sassia, Italy, was the model for medieval and early modern European hospitals, where the cure of the body was generally secondary to the care for the soul. In the Enlightenment period, the role of hospitals changed: these institutions became pivotal to the public provision of medical care. The most significant one from this period was certainly the Allgemeines Krankenhaus in Vienna, founded in 1784. Its establishment was closely preceded or followed by many similar, although more modest, projects throughout Europe (4). Yet, in comparison with Dubrovnik (Ragusa) or Zadar (Zara), not to mention larger European centers where the projects of building hospitals were far more expeditious, the city of Split in Southern Croatia lagged behind. During the 17th and early 18th centuries Split had only a few hospitals for the poor, few military hospitals, and provisory shelters used mainly in the times of plague or other epidemics, which were all in poor condition (5).

Building a new city hospital in Split therefore became a matter of considerable public interest, particularly when the initiative for the establishment of an institution for the care of the poor was taken over by a rich and highly esteemed citizen Ante Ergovac (5-7). Ergovac bequeathed 1000 zecchins for that purpose in his testament of January 3, 1783 M. V. (M.V., or More Veneto, was a Venetian way of writing dates. Every date of January and February marked with M. V. had to be moved into the next year. Thus, the testament of Ante Ergovac was written on January 3, 1784) (8). After his death, his brothers Frane and Petar were appointed the executors of his will. Although they tirelessly worked to realize the philanthropic idea of their brother, his charitable donation was not sufficient for the project to develop. The materialization of the idea depended on an intricate network of socio-political and administrative factors.

Bureaucratic entanglements

On June 16, 1785, Ergovac brothers appealed to the governor (Provveditore Generale) of Dalmatia and Albania, Francesco Falier, to grant them the permission to build the hospital for the poor and to donate the state land for this purpose. The brothers suggested that a location outside the city, northeast of the St. Arnir monastery, be used. They also proposed to set up a pawn-shop, the profit of which (6% interest rate on the 1500 zecchins capital) would be used to cover the costs of running the hospital (8). The count captain (conte capitano) of Split sent their application to the governor Falier on June 18, 1785 (9). The application was accompanied with a topographical plan of the building drafted by the public surveyor Petar Kurir on June 16, 1785. On the right-hand side of the plan, there is a description of the position of the building (10):

On June 16, 1785, in Spalato Regarding the command sent to the undersigned by the Serene Government in its supreme letter of the 15 of the current month, I went to the state land marked with the letter ‘A’ and located north-east of the St. Arnir Monastery. The plot of land is shown in this plan, with one corner on the south-east side of the picture A 36 feet away from the opposite corner of the bell-tower of St. Arnir; the south-west corner is 32 feet away from the opposite corner of the stone bench outside the Pistura Gate. The longest side of the rectangle on the picture A is 100 feet long on the north-east, and the shortest is 80 feet on the south-east. The total surface is 8,000 square feet. The land is in the free public disposition. Faithfully, Petar Kurir, public surveyor, swears

This application shows that the hospital project began in 1785 rather than a year later as stated in the historiography.

Just before the end of his mandate, on November 2, 1786, the governor Francesco Falier had sent a letter of support to the Senate for the application of Ergovac brothers (11). Previous historiography of the Civic Hospital in Split claimed that the governor approved the application of Ergovac brothers and that the municipal council donated them a parcel of land to erect a hospital (5-7). However, the fact was that neither the governor nor the municipal council had jurisdiction to either approve the application or grant the use of the land for hospital construction. The power over the state land lay in the hands of the supreme governing body, the Senate, as may be concluded from numerous key documents preserved in the State Archives in Venice and Zadar. Consequently, scholars failed to investigate further the complex circumstances and difficulties surrounding each phase of the Split hospital project.

On August 18, 1787, the Ergovac brothers had to reappeal to the authorities, but this time they guaranteed to cover all additional expenses of building the hospital. The pawn-shop was not mentioned, but they asked to be given the noble title of count (12). A new topographical plan of the hospital was drafted by the public surveyor Franjo Antun Kurir on November 22, 1787 (Figure 1). It was a copy of the previous one, except that it contained the parcel dimensions (13). On January 22, 1787 M. V. (January 22, 1788), the public surveyor Petar Kurir testified that building the hospital on the parcel inside the Corner fortification would not harm either public or private interests (14).

Figure 1.

Copy of the topographical plan with the description of the position of the future hospital building prepared by the public surveyor Franjo Antun Kurir on November 22, 1787 (13).

In 1789, the subsequent governor also expressed his supporting opinion on the project to the Senate (15). However, although seen as praiseworthy and necessary, the project proceeded no further. Finally, on the request of the Magistrate in charge of the state land (Magistrato sopra feudi), on August 30, 1790, Frane Ergovac swore on behalf of his brother and himself to erect a hospital that could accommodate 200 persons. Construction work was supposed to start immediately after the allocation of the parcel and approval of the noble titles. Frane Ergovac also promised to cover all expenses that exceeded 1000 zecchins bequeathed by his late brother and to purchase hospital beds (16).

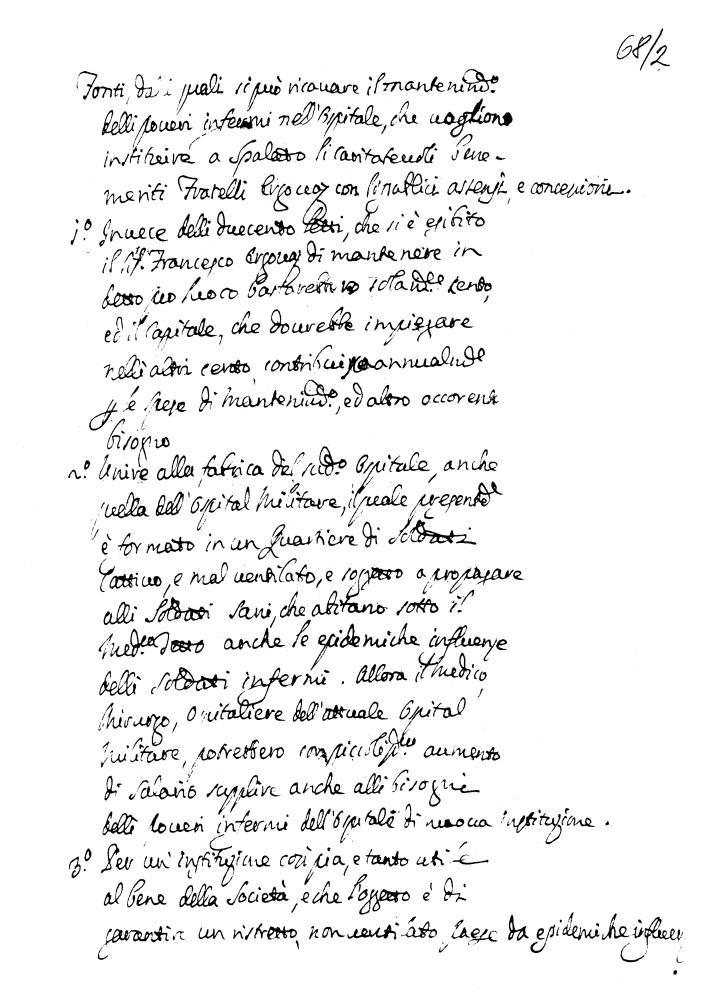

On September 1, 1790, the Magistrate sent a note to the Senate in which he expressed his support to all Ergovac’s requests (17). Eight days later, on September 9, 1790, the Senate responded favorably as far as granting of the title of count to Ergovac brothers was concerned, but requested a more detailed financial plan for the hospital project (18). The strategy of financing the future hospital, presented in a document kept in the State Archives in Zadar, discusses alternative ways of covering the inpatient expenses (Figure 2). The first way was to reduce the number of hospital beds from the promised 200 to 100. The money thus saved was to be redirected to the maintenance and other hospital expenses. The other way was to merge the future hospital with the Military Hospital, located in the army camps. The Military Hospital was housed in a dilapidated building with poor ventilation system, thereby contagion often spread from the sick to healthy soldiers who were accommodated in the hospital. However, the merging of the two hospitals would allow a physician-surgeon, or a military surgeon, to have higher salary and offer treatment to poor civilians as well as soldiers.

Figure 2.

Description of ways to cover the inpatient expenses in the Civic Hospital in Split (19).

The document further argued that such a hospital should be supported by the community, because it would be of use to everyone and would prevent further spreading of epidemics in the overcrowded city. Therefore, each citizen was to contribute for the hospital proportionally to their means, and the Jewish community was also to provide a modest annual contribution. The supreme government allowed Jews to keep shops throughout the city, so they were exposed to epidemics and contagion just as everybody else. For the benefit of the institution useful to everyone, the document continued, it would be fair if each owner of a market stall or shop would be taxed a small amount on a monthly basis. The confraternities were also to be taxed proportionally to their income. Lastly, potential sources of income were the citizens’ testaments. It was the duty of the city notary to remind and encourage the testators to make charitable bequests.

The document clearly reveals the basic attitude of the central government toward the establishment of a medical institution in Split. In their opinion, the financing of the new hospital belonged exclusively to the charitable domain (19). For the government, it was clearly not a project that merited allocation of the state funds. It is, therefore, not surprising that the city fathers of Split eventually informed the governor Angelo Diedo on December 10, 1790, that the municipal finance office could not afford to allot an annual sum for the hospital (20). Thus, the whole project was back at the beginning.

Years passed and the project remained at halt. Only new requests kept on arriving and the government kept on replying with further inquiries and increasingly difficult terms for the investors to meet. Yet, in spite of all that, the investors did not give up. They obliged themselves by another document not only to provide the means for the hospital building and beds for 200 persons, but also to deposit with the public authorities a capital of 1000 zecchins to be released in installments to pay for the maintenance of the hospital (21).

Project and vision of Split Civic Hospital

The story of the Civic Hospital in Split, from a philanthropic idea to its final erection, is revealing in several aspects. It shows how disease was understood in those times, as well as the means by which a group established the forms of assistance, and how it reacted to poverty and disease. The plan drafted by the public surveyor Franjo Antun Kurir on October 15, 1791, uncovers some of these aspects.

According to the plan, the first floor was intended for the healthy, whereas the second floor was reserved for the sick and the convalescent. The windows were equipped with iron bars, and the entrance was on the southern side of the building. Male and female patients were accommodated separately (22). In October 1791, the building supervisor Zuanne Midoleo estimated the basic construction costs of the hospital, supposed to accommodate 200 persons, at 1911 zecchins (23).

The hospital was intended primarily for the poor, whose treatment was fully subsidized. However, after the recovery, the poor could receive no further benefits except free accommodation. Thus, the income for its construction and operation was supposed to come from charitable bequests and public welfare funds. The hospital would employ medically-trained staff, with a professor making a diagnosis on admission and deciding on the treatment in agreement with the military surgeon. The surgeon, in addition to receiving his military salary, was to be paid extra by the city for the treatment of the poor civilians.

The abundant archival material that we reviewed contained numerous mentions of various potential sources of hospital income, such as the public treasury, contributions of the confraternities, and citizens’ wills with the encouragement of the city notary. These, along with the reduction of the number of hospital beds to 100, were used by the investors to open up some room for negotiations with the authorities, which lasted for many years.

Yet, only by the precise declaration of the investors that they were not only prepared to cover the expenses for building the hospital, but also guaranteed to allocate 1000 zecchins for its later running, the governor Angelo Diedo asked the Senate to speed up the decision on building of the hospital (24).

Criticism of the authorities with respect to hospitals was a common place of economic analysis in the 18th century (25). The sick in hospitals were seen as a double burden to the society: they could not provide for themselves while in hospital, thus the society provided for them (medical care, food, and accommodation). But while in hospital, the sick could not provide for their families, which were thereby left to even greater poverty. At the same time, hospitals as pestilential closed places favored the spread of diseases and created new ones. The patients were sex-segregated, but were not accommodated according to their diagnosis, which multiplied the diseases and increased expenses.

Erection of Split Civic Hospital in 1797

On the basis of the certified confirmation by the public surveyor Franjo Antun Kurir on May 17, 1794, that he had inspected the empty building plot inside the Corner fortification (26), marked with the letter “A” in the plan prepared by the public surveyor Petar Kurir on June 16, 1785 (10), we argue that the Civic Hospital in Split was neither erected in 1792 nor officially opened in 1794 as stated before. At that time, the hospital construction had not even begun.

What actually happened was that on August 30, 1794, after nine long years of tireless efforts, the Senate finally decided to allocate the parcel to build the hospital and to grant the requested titles of counts to Ergovac brothers. The brothers were bound to cover all construction expenses that exceeded the sum bequeathed by their late brother Ante, as well as all other expenses that they had guaranteed to pay. They also had to supervise the construction works, to make sure they were in accordance with the plan and for the intended purpose (27).

On August 8, 1796, governors in charge of the state land inscribed all members of Ergovac family in the Golden Book of Titles (Naslovnik). From that date on, they were legally allowed to use the title of count (28).

A document from the State Archives in Zadar, dated April 12, 1797, informs of the completion of the building works, full five years later than reported in the historiography. Right after that, the First Plan for the Organization and Management in 17 articles was composed (Figure 3 and web-extra) (29).

Figure 3.

The beginning of the First Plan for the Organization and Management of the Civic Hospital in Split, dated April 12, 1797 (29).

Discussion

This study necessitated a thorough review of the older historiography and an investigation of the previously unpublished archival sources, largely kept in the State Archives in Venice and Zadar. It illuminated the complex interplay of circumstances surrounding the foundation of the Civic Hospital in Split and the attitude of the authorities toward the new medical institution.

Our findings threw a new light on the history of the hospital and corrected factual errors in some of the older literature (1,5-7). Historiography mentions either the public surveyor Petar Kurir (1,5-7) or an unknown foreigner in the Venetian service (30) as the author of the hospital project. On the basis of the documents found in the State Archives in Venice, we argued that the hospital project was drafted by the public surveyor Franjo Antun Kurir on October 15, 1791.

The comparison of the original plan of the hospital with the later Split city maps showed that the final building had not entirely followed the plan (31,32). The hospital wing on the southern side was not erected, which resulted in the smaller number of beds than originally intended.

The realization of the philanthropic idea of establishing a Civic Hospital in Split conformed to the contemporary representations of such institutions. Care for the lower social strata had, from its beginning, an ambivalent character. On the one hand, it was characterized by charitable aspirations and on the other by the need to isolate the potential source of contagion – the poor, frequently accused of living in unsanitary conditions. Everyone in support of the hospital project used rhetoric firmly based in the following arguments: “It is obvious that Spalato lacks a public shelter for the ailing poor who lie on the city streets or mix with others in crowded, mostly underground dwellings. They die there in poverty and exhaustion, after having transmitted onto us the diseases that they have been struck with” (17).

At the end of the 18th century, the prevalent miasmatic-contagion concept of the disease causation dominated over the perception of disease as an individual and private problem. Disease was a phenomenon that required attention of the entire community. Yet, the development of such an attitude was extremely slow and gradual and did not influence much the main building or organizational strategy of the Civic Hospital in Split (Spalato). On the contrary, the vision of future hospital’s organization and medical care management, including intention to merge it with the Military Hospital, which pestilential character was eminent, proves that it was primarily the economic factor that influenced the decision makers, notwithstanding the dogmatic discourse on the nature of disease used mostly as an argument for creating such an institution.

The First Plan for the Organization and Management of the Civic Hospital in Split (translation by Tatjana Buklijaš)

To soothe the suffering of his neighbor, to help the unfortunate, has always been the work of the fellow man, and in particular of the late Ante Ergovac from Spalato. Touched by the poignant fate of the poor sick, who without help and shelter often collapsed exhausted by hardship on the city streets, as his last will he ordered to erect at the expense of the family a poorhouse, which would offer at least a charitable shelter to the poor sufferers, where physicians would provide care toward their recovery, where they would be given a bed to rest, and where the servants of God would supply comfort for their suffering lives. Such a charitable institution was established by the love of Frane and Petar Ergovac, his brothers, no less charitable than his last gracious will. The State gave to this good family a title, for their services to the humankind and to the Homeland, as they deserved to be specially satisfied by the supreme grace of the State, and also immediately supplied a suitable state land for this charitable deed, as a contribution from the state finances.

Building of the institution has now been completed and placed under the care of the respective Municipal Society, which we founded in order to prepare a Plan for running of the institution and for its better operation, as well as for the realization of certain incomes that should serve to help the patients, of which there will be many. We are now presenting the completed Plan, and in order to manage the poorhouse as well as possible, we are here giving the rules, ordered and completed under our rule and with our authority:

1. The charitable hospital erected outside the Spalato city gates at the expense of the founding family Ergovac is placed under the care and protection of the State.

2. Due to the current state of the hospital incomes, the charitable hospital will admit the poor only for a day or night hospitalization on the ground\floor, situated on the lateral side of the new building, men separate from women, the dying away from the beds of Ergovac brothers planned for the severely sick. Later, if the income increases, the poorhouse will admit the poor suffering from less severe conditions.

3. In relation to the first order, the priority will be given to the sick from this city, then its districts, then the province, then the rest of the Venetian State, and finally those from the subordinate lands who find themselves in the State.

4. Until an adequate income is found, offered to the hospital by the faithful who love their neighbor, charity will be permitted in the neighboring towns and used to support the poor who accidentally fall sick in the hospital, as well as for all other needs of the poorhouse. All uses of the charity that are not expressly authorized by the State authorities will be abolished.

5. The Society will appoint a curate, a pastor and a lay person: the first priest to provide spiritual care to the poor in the fear of the God. Rights of the parish priest will not be violated and the parish priest will not be relieved of his duties, which he must perform. The others are and will be there to offer services necessary to each of the sexes separately.

6. As for the burial of the poor who will die in the hospital, nothing can be added to the prescribed regulations, because this charitable service is for everyone conducted by a specific institution: pauper corpses are buried by a charitable confraternity from Spalato, known under the name of Good Death.

7. Care for the hospital should be assigned to the Lay Society which has been already founded. It will be composed of forty persons, selected by lot from the nobility, civil and merchant estates, among those who have that title at the moment, and the number should never increase, and one member can never take a place of another except in the case of death. These members will be received in the Society at least with two-third of votes and upon their receiving, each of them will supply a charitable contribution to the income of hospital, the amount of which he will decide for himself.

8. On the Feast day of St Lazarus, the managers will be elected from the members of the society, who will run the hospital. They will be elected for a period of one year, and they will perform their duties interchangeably for a period of one month. They will frequently visit the poorhouse, so that the poor do not lack the necessary merciful help.

9. It is the duty of the monthly manager to supply the hospital with all necessities. In the case of overloading the first among the elected manager should manage the income and, at the end of his mandate, compose a list of necessary goods for his successor and the notary, elected pro tempore with two-third of votes. One week after the Feast day of St Lazarus, all three managers should present a report on the hospital management to the congregated entire society membership.

10. A chest locked with three keys, one for each of the managers, will be kept in the hospital. This chest will be used to keep the money that belongs to the poorhouse. It will be open only with the agreement of all three and in the presence of at least two managers. If the managers fail to obey the articles 8, 9 and 10 of this decree, and that in our opinion will never happen, they will not be allowed to perform any of the hospital services.

11. In addition to the forty society members, the superiors will ask all gentlemen professors of medicine and surgery in Spalato and neighboring towns to take part in this charitable body, to offer help and professional care to the patients of the hospital, if their number is in accordance to the one prescribed in the preceding articles and in the article four. It would be appropriate for their help to be free of charge, or charitable, and we expect them to be faithfully ready to wait for the moment when the poorhouse will have sufficient income to adequately award them for their services. These will be organized in weekly shifts, starting with the oldest professor in the first week, while others will follow on weekly basis. At all other times, they must be free from other duties in the hospital or in the Hospital Society, in which they will always be able to take part with their vote. If a professor would like to continue treating a particular patient outside his shift, his successor will not be allowed to prevent him from doing so.

12. The prescribed number of forty current members is allowed to preside, vote and manage. Provided they have the majority of votes, the Hospital Society may also be joined by persons of both sexes, named Divoti, who will be expected to provide a charitable deed for the poor. The associated Divoti will contribute charity, at the amount they perceive sufficient, upon their joining the Society.

13. To avoid frequent decrees and orders, often harmful to the good management of the poorhouses: we order that no decision proposed by the Society may be valid or voted for unless it has the support of three-quarters of the membership. All decisions related to the addition of a new or deletion of the old articles in this Plan, must not be voted for unless previously read in front of the entire membership. The voting may follow eight days after the reading but the four-fifths majority will be required or, even if the decisions are approved by the membership, they will not be valid until confirmed by the Supreme Government in the Province. The Society Congregations must always have the approval of the local representative of the Supreme Government.

14. If a restless spirit finds itself in this charitable body and starts disrupting the harmony in the Society, a decision may be brought to strike him from the membership, which must be supported by the majority of votes and which he will have to accept.

15. As in all civic bodies in the City, members must give annual contribution in a certain amount, which under the title ‘osnova’ [basis] is then transferred to the respective civic institution, it will be the God-obeying duty of the current members and the associated Divoti to pay every year on the Feast day of St Lazarus to the managers of that month 12 Dalmatian liras per head, which will be used for the benefit of the hospital poor. Only professors of medicine and surgeons are released from paying that duty, because of the care that they will supply to the sick poor.

16. It is the duty of the city notaries and parish priests in Spalato and its district, in charge of testament-making in the city and its territory, to suggest to the testators to leave something for the benefit of the said hospital. If he fails to do so, he will have to pay himself 20 ducats in the bank notes used in the province, the sum which immediately will be transferred to the poorhouse funds. Spalato notary must inform the managers of the hospital of each will that contains any bequests to the hospital.

17. In order for this charitable institution to have a certain form, and to be able to provide help to the unfortunate, the articles of this regulation must be read on the day of the election to the duties in front of all members of the Society, so that they are clear to everyone. If they are not read, than they will not be legally valid.

These seventeen articles order all affairs of the Institution and the administration of the poorhouse and the Presiding Society. We accept the efforts of His Highness, the State representative of this jurisdiction, and three managers, to attentively supervise conformance with these regulations. We preserve the right to offer our advice, also about the project income fund, into which this Society must give us insight, as soon as all requested inquiries in this important article are exhausted.

In Zara, on April 12, 1797.

The plan of the foundation of the hospital, which has already been completed thanks to the great mercifulness of Ergovac brothers and the presiding Lay Society, to the attentive supervision of which it has been assigned, has deserved this duty because by accepting the spirit of the regulations it sought to determine the imagined regulations which were supposed to be included in this basic decree. In reply to Your Highness, I commend your efforts in ordering the managers to read this decree to all society members, and the subsequent inscription into the book of Your Regulations.

The goal of the established institution is to inspire charity in the society members, so that they never allow a lapse or neglect in respect, so that their care, together with that of the founders and under the protection of the state help, continually soothes the suffering of the people, who have the right to mutual love and brotherly help of their neighbors.

In Zara, on April 12, 1797 (29).

Acknowledgment

Dr Tatjana Buklijaš translated the historical documents into English.

References

- 1.Kraljević Lj, Boschi S, Sapunar D. A contribution to the history of health services in Split. Croat Med J. 1993;34:153–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gamulin S. Medicine in Split – historic background. Croat Med J. 2000;41:359–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benyovsky I, Buklijas T. The confraternity and the hospital of Santo Spirito in Split in the medieval and early modern period. Zbornik Tomislava Raukara. [in Croatian]. In press 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porter R. The greatest benefit to mankind: a medical history of humanity from antiquity to the present. London: Harper Collins Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keckemet D. Health and hospitals in Split till II World War [in Croatian]. In: Uglešić B, editor. 190 years of Split hospital [in Croatian]. Split: General Hospital in Split; 1984. p. 13-36. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keckemet D. Old Split hospital 1794-1964 [in Croatian]. Split: Novinsko-izdavačko poduzeće “Slobodna Dalmacija”-Split; 1964.

- 7.Keckemet D. Beginnings of the Split hospital [in Croatian]. In: Reic P, editor. 200 years of Split hospital (1794-1994) [in Croatian]. Split: Split University Hospital; 1994. p. 11-23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.State Archives in Venice. Application of Ergovac brothers [in Italian]. Provveditori da terra e da mar, b. 651.

- 9.State Archives in Venice. Telegraphic despatch by the count captain to the governor [in Italian]. Provveditori da terra e da mar, b. 651.

- 10.State Archives in Venice. Topographical plan of the public surveyor Petar Kurir on June 16, 1785 [in Italian]. Provveditori da terra e da mar b. 651 dis. 1.

- 11.State Archives in Venice. Telegraphic despatch by the governor Francesco Falier to the Senate n. 151 [in Italian]. Provveditori da terra e da mar, b. 651.

- 12.State Archives in Venice. Repeated application of Ergovac brothers [in Italian]. Collegio, Suppliche di fuori, filza 526, alla data 1787, ago.18.

- 13.State Archives in Zadar. Copy of the topographical plan from 1785 by the public surveyor Franjo Antun Kurir on November 22, 1787 [in Italian]. Generalni providur Angelo Diedo 1790-1792. Volume 5. Pozicija jedina. L. 1-69.

- 14.State Archives in Venice. Confirmation of the public surveyor Petar Kurir [in Italian]. Senato, Mar, filza 1231.

- 15.State Archives in Venice. Telegraphic despatch by the governor to the Senate on August 30, 1789 [in Italian]. Senato, Rettori, filza 411.

- 16.State Archives in Venice. Declaration of Frane Ergovac [in Italian]. Senato, Mar, filza 1231.

- 17.State Archives in Venice. Scripts of Governors in charge of the state land [in Italian]. Senato, Mar, filza 1231.

- 18.State Archives in Venice. Decision of the Senate on September 9, 1790 [in Italian]. Senato, Mar, reg. 244, cc. 261r-262r (cartulazione antica 60r-61r).

- 19.State Archives in Zadar. Sources of covering the expenses of patients' maintenance (in Italian). Generalni providur Angelo Diedo 1790-1792. Svežanj 5. Pozicija jedina. L. 1-69.

- 20.State Archives in Zadar. Letter of the Split city fathers to the governor Angelo Diedo (in Italian). Generalni providur Angelo Diedo 1790-1792. Svežanj 5. Pozicija jedina. L. 1-69.

- 21.State Archives in Venice. Declaration of Ergovac brothers [in Italian]. Provveditori da terra e da mar, b. 658.

- 22.State Archives in Venice. Plan of the Split Hospital made by the public surveyor Franjo Antun Kurir on October 15, 1791 [in Italian]. Provveditori da terra e da mar, b. 658 dis. 2.

- 23.State Archives in Venice. Expense-account for the construction by the building supervisor Zuanne Midoleo [in Italian]. Provveditori da terra e da mar, b. 658.

- 24.State Archives in Venice. Telegraphic despatch by governor to the Senate on May 8, 1792 [in Italian]. Provveditori da terra e da mar, b. 658.

- 25. Foucault M. The birth of the clinic. London: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.State Archives in Venice. Certified confirmation by the public surveyor Franjo Antun Kurir on May 17, 1794 [in Italian]. Senato, Rettori, filza 411.

- 27.State Archives in Venice. Decision of the Senate [in Italian]. Senato, Rettori, reg. 171, cc. 90r-91r = pp. 123-5: 1794, ago. 30.

- 28.State Archives in Venice. Registration of Ergovac family in the Golden book of titles [in Italian]. Provveditori sopra feudi, reg. 1060, pp. 312-4: 1796, ago. 8.

- 29 State Archives in Zadar. First Plan for the Organization and Management of the Civic Hospital in Split [in Italian] Generalni providur Andrea Querini 1795-1797. Book 1. L. 1-250.

- 30.Keckemet D.Projects of the Restorations of the Hospital in Split in 19 century [in Croatian]. Acta historiae medicinae stomatologiae pharmaciae medicinae veterinariae1987. 27:127-40 [Google Scholar]

- 31.City Museum of Split. Plan of Split by Vicko Andrić in 1819.

- 32.City Museum of Split. Plan of Split by Vicko Kurir in 1826.