In an attempt to reconstruct the function of the last leprosarium in Croatia, situated in the little town of Metković in the Neretva valley, we used local folk tales and compared them with different data sources, such as register of deaths in the Roman Catholic parishes in Metković and the nearby village of Vidonje, archived local newspapers, building documents, and different artifacts from the beginning of the 20th century. We identified individuals and families who were treated in the leprosarium during its existence from 1905, when it was built, until 1925, when it was closed down.

We analyzed why the Neretva river valley was chosen for the isolation of lepers. It seems that the geographical position of the region, close to the endemic seat of the disease in the neighboring Bosnia, was more important for the decision to build the leprosarium than the incidence of leprosy or some recent outbreak of the disease in Croatia. Building of leprosariums, such as this one in Metković, was a part of tradition of separating lepers from human community. This was considered as a socially and medically justified behavior in a time when it was not possible to identify the cause of leprosy and apply the proper treatment.

During centuries, leprosy has been a phenomenon which exceeded exclusive meaning of its pathological entity. At the theurgic level, the disease appeared as the symbol of moral degeneration. Because of that it was mainly cured by clerical caritas, outside the competence of the medical profession. The actual transition from religious to medical competence in the framework of contemporary concept of Hansen’s disease was gradual, and in all its phases was burdened with the seal of stigma of a bygone time (1,2).

This chronic granulomatous infection caused by Mycobacterium leprae, with different clinical manifestations that depend on the immune response of the host, was brought to Europe by Greek soldiers on their return from Asia in the 3rd century before Christ (1,3). In the 7th and 8th century, the number of lepers steadily increased, while in the 13th century, during the Crusade wars, it rose to pandemic proportions. In that time a great number of leprosariums was built all over Europe. Croatia was not an exception, with the oldest leprosarium documented in Dubrovnik in 1272 (4). In the 15th and 16th century, leprosy abated and became a very rare disease for reasons that are still a matter of debate. However, it came back in the 17th century during the Ottoman Empire expansion to the Balkan Peninsula. In Bosnia and Herzegovina it rose to epidemic proportions and reached the border of the former Dubrovnik Republic, today the southern Croatian border (5). Not enough records were preserved that can help us build the entire picture of leprosy in that time. The available information is mainly related to the measures of isolation, in most cases in the statutes of Croatian medieval towns and communes. Other sources are testaments and estate inheritance given to the lepers by wealthy individuals, found in the notary documents and scarce written documents of isolated patients that could be found till the middle of the 20th century in Croatia.

Here we present the information on the last leprosarium in Croatia, which was established near the town of Metković in 1905, when leprosy did not pose a particular danger to the domestic population anymore. We analyzed the circumstances of its foundation, with the presumption that the geographical site of this region and the vicinity of the endemic locus in nearby Bosnia were more important for its foundation than the frequency of the disease or the outbreak of new cases of leprosy in Croatia.

The choice of the Neretva river valley with its metaphoric name “doomed by God,” as the leprosy isolation location well depicts the concept of moral stigma that was for centuries attributed not only to leprosy but also to the regions marked by underdevelopment, poverty, and diseases, which made them a place of choice for building leprosariums.

Although this was one of the last leprosariums in Europe, preserved records about it are exceptionally poor and cannot be found even in the major archive institutions such as Public Record Offices in Zadar and Dubrovnik, Public Record Office of the Ministry of the interior of Republic of Austria and Public Record Office of the Republic of Hungary. Therefore, we based our work on the rare preserved documentation, mostly from the Register of Deaths in Roman Catholic parishes in Metković and in the nearby village of Vidonje, contents of local newspaper, as well as from the local oral tradition, building documentation, and secondary sources.

Valley of Neretva river «Doomed by God»

Reports related to leprosy in Croatia at the end of 19th century and in the first decades of the 20th century are mainly about the sporadic cases of the disease, especially on the Croatian coast, island of Krk, Vis, and middle Dalmatia and are mostly published in the journal Liječnički Vjesnik (5,6). The disease was linked with the poor hygienic conditions of the impoverished population. Bonetić, for example, describes two cases of the disease in coastal Croatia, and clearly points to poor social and hygienic conditions as factors in the transmission of the illness (6). Constant fear of leprosy described in literature was also noticeable in the columns of Croatian physicians in the first part of the 20th century (7). There is an impressive article about a mother from the island of Krk, who was hiding her child during the day and bringing it home during the night in order to save him from frightened local people (8). We can also find cases when people with amputated extremities were stigmatized as lepers, as well as cases of runaways from the imposed isolation (9,10). The discovery of the etiology of leprosy in the last decades of the 19th century could not resolve all the diagnostic doubts. Therefore, there were still some misdiagnosed patients, most frequently with Mal de Meleda, genetic disease typical for the inhabitants of the island of Mljet (11). In the time when the leprosarium was built in Metković, there were 317 registered cases of leprosy in the neighboring Bosnia and Herzegovina, while in the whole of Croatia there were only 17 registered cases during the 20th century (5,12).

Neretva river valley is today the western part of Croatian Dubrovačko-neretvanska County. The lower part of the river basin has had great geostrategic importance even since the antiquity (Figure 1). It is a border territory between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina with the town of Metković which, thanks to the merchant trade, became its economic, cultural, and administrative center. This valley had provoked fear among Dalmatian population ever since the medieval times and was given the name of “Neretva doomed by God.” The first written record of this expression is found in the travelogue “Viaggio in Dalmatia” from 1774 by Italian priest Alberto Fortis (13).

Figure 1.

Geographical position of the Neretva valley, with the town of Metković – Leprosarium position.

Describing his two-week visit to this region, Fortis, among other things, quotes Giuseppe Puiatti (1701-1760), a doctor from Korčula, and the professor at Padua University, who in his work “De Morbido Naroniano Tractatus,” writes about frightening living-conditions in the Neretva region affected by malaria, pointing out that there even birds frequently fall dead from the evaporation of polluted air. Fortis did not know where the expression “Narenta maledetta da dio” (Neretva doomed by God) came from, but he said that it became a proverb among Dalmatian population because of hard conditions of living in that region (13).

Neretva valley was under west-European health, administrative, and military jurisdiction since the Middle Age: first under the Venetian rule (1694-1797) followed by Austria (1797-1806), France (1806-1814), and finally Austro-Hungarian monarchy (1814-1918).

While public health measures in the Neretva region were based on European tradition, health conditions in the neighboring country of Bosnia and Herzegovina were totally different. It is well known that the European medical practice and public health measures came in Bosnia and Herzegovina at the time of Austro-Hungarian rule. Before that, health care availability was selective and dependent on the national and religious background. Better to say, it was established only for the Ottoman army and officers. For the civil population, especially Christians, medical care was unavailable and living conditions were difficult. This was the reason why Bosnia and Herzegovina, under Ottoman rule, was the source of different infectious diseases (14). Franciscans priests were the main caregivers and used their own translations of the west-European medical textbooks for treating the sick (15-18).

On the other side of the border in Neretva valley, in Croatia, the population lived in hard economic, social, and health conditions, in hunger and misery at the beginning of the 20th century. According to the well-known concept of physiology of poverty, hard work and lack of food lead to insufficient nutrition and alcoholism, at that time the common habit in the lower part of Neretva region, which caused further increase in poverty and malnutrition. The combination of these factors lead to the diminished immunity and increased incidence of serious lethal diseases such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, typhus, dysentery, and malaria (19). Tuberculosis frequently attacked lepers because of their impaired immune system. Poor living conditions and continuous close contact with the diseased led to the formation of the endemic areas of leprosy. One of these was formed in the village of Vidonje some 10 km from Metković.

Poverty, ignorance among the underprivileged, proximity of Bosnia and Herzegovina, geostrategic location on the main roads, as well as the existence of the smaller endemic seat of leprosy in the village of Vidonje were probably sufficient reasons for the foundation of the leprosarium. The basis for this conclusion can be found in the article “Leprosarium” in Dalmatian gazette “Smotra” published for the opening of the leprosarium. Here we can find data about spreading of leprosy during the Ottoman conquest of this territory, the number of leprosy cases in Dalmatia, the way leprosy spread through the region, and the importance of isolation of the diseased in this leprosarium. In 1905, there were altogether seven cases of leprosy in Dalmatia. “That day in Leprosarium there were four patients from the village of Vidonje, while a notification was sent to other districts to send their cases as soon as possible” (20).

Opening of the last leprosarium on the territory of Croatia

The leprosarium was opened on March 15, 1905 and this event was well covered in contemporary newspapers, showing the significance of the newly opened institution for the public (Figure 2). Dr Karl Vipauc (1851-1950), who was the regional health supervisor for Dalmatia, personally supported the foundation of the leprosarium in Metković (21). Beside Dr Vipauc, the head of the district, Dr Josip Grioni, was also present at the opening ceremony.

Figure 2.

Opening ceremony of the leprosarium on March 15, 1905.

On that occasion, “Narodni list” (People’s Gazette) in the article titled “Lepers,” wrote: “We received the following letter from Metković on March 23: We cannot speculate that our report in your magazine made up the mind of the authorities to bring the lepers from Vidonje to the new hospital but it certainly hastened their decision. Soon after the article in “Narodni list,” our regional health supervisor Dr Vipauc hurried to settle those poor souls in a comfortable shelter. A stubborn patient Ivan Sentić chose to stay in the district detention rather than move to the new leprosarium with his mother and brother. County doctor Dr Ljubić was going around the mountains and rocky canyons of Vidonje to decontaminate flats and burn the clothes left by those poor lepers. In the new hospital they are taking good care of the lepers, keeping them clean and well fed, that we should all be proud about” (22).

One should notice specific irony as well as cynicism of the unknown reporter, who calls the leprosarium a “hospital.” From the criticism directed at those who had still not arrived to the leprosarium, it is obvious that the isolation of lepers had incited great public interest. Good conditions in the leprosarium are specifically mentioned, trying to clear the public from the guilt of excommunication of the diseased for a lifetime. As we can see on the photograph taken at the opening ceremony, the diseased and their companions were put in front and all the distinguished guests were behind and aside at a safe distance.

The leprosarium was situated in the region called Pavlovača, some 2 km from the town of Metković and above the main road connecting Metković and Dubrovnik. In front of the building was an unpaved cascade terrace serving as an open daily lounge with a wonderful view over the Neretva valley, its delta, and the surrounding mountains. It was built at the altitude of some 50 m above the sea level, surrounded by a beautiful forest, protecting the building from the cold north winds. Since they were settled on the rocky terrain, the foundations and walls were built from the pieces of rock bound with mortar in the building manner traditional for that time. The leprosarium consisted of two one-story buildings, the bigger one of 115.60 m2 and the smaller one of 61.59 m2 (Figure 3). The facade and inside walls were plastered, traces of which can be seen today on the ruins of the buildings. The smaller building was covered with a double-row wooden roof, while the bigger one had a multiple-row wooden roof completed with the traditional half-round roof tiles. Behind the bigger building, there was a lavatory with a separate entrance from the outside. The lepers were allowed to grow vegetables for their personal needs.

Figure 3.

Ground plan of the remains of the leprosarium.

Mr Petar Vuica (died in 1956) was in charge of regular daily control and care for the patients, while the health care was provided by the local physician, Dr Šime Ljubić. Inside the complex, the local priest, don Luko Gabrić (1835-1918), sometimes performed the holy mass. In the private collection we find the tweezers that he used to present the sacrament of Holy communion to the lepers, avoiding direct contact with them (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Tweezers which were used by the priest during the Holy mass to give the communion to the lepers.

Residents of “The Lepers’ Houses”

To reconstruct the details about the isolated lepers we analyzed the data from newspapers, literature, and from the Register of Deaths in Roman Catholic parishes of Metković and Vidonje (Table 1). Altogether, there were eight persons isolated in the leprosarium during its existence, most likely the members of three families (Sentić, Ilić, and Milinković).

Table 1.

Known patient data with outcome of the disease among lepers from the Metković leprosarium

| No | Name | Sex | Status | Source | Reference | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Matija Milinković |

F |

patient |

book text |

25 |

unknown |

| 2 |

Milinković |

F |

escort |

book text |

25 |

unknown |

| 3 |

Matija Sentić |

F |

patient |

register |

22 |

died 1922 |

| 4 |

Ivan Sentić |

M |

patient |

newspaper article, (Neumann) |

25, 24 |

unknown |

| 5 |

Bartul Sentić |

M |

escort |

newspaper article |

21 |

emigrated to the USA |

| 6 |

Bartul Crnčević |

M |

patient |

register |

23 |

died 1917 |

| 7 |

Ilić |

F |

patient |

book text |

25 |

unknown |

| 8 | Ilić | F | escort | book text | 25 | unknown |

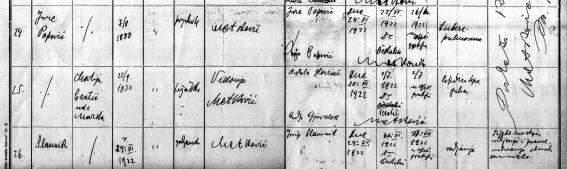

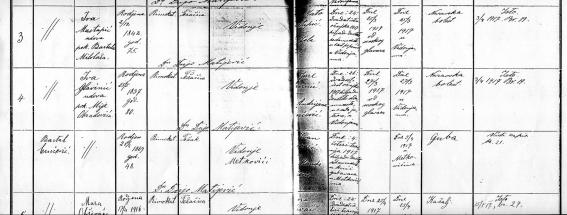

The most complete record we could find was for Matija Sentić, born in 1856. There are written data about her death on June 30, 1922. She was buried the day after, on July 1, at the local district cemetery in Metković. The local priest, Leonard Bajić, performed the funeral service and the leprosy was stated as the cause of death (23) (Figure 5). In the Registry of Deaths of Vidonje parish, we found the evidence for Bartul Crnčević, born in 1869, who died in the lepers' house in Metković on April 4, 1917, and was buried the day after. The funeral service was performed by the local priest Luigi Donelli (24) (Figure 6). For the rest of the isolates we could not find the data in the Registers of Births, Deaths, and Marriages in the parishes of Metković and Vidonje, so we completed the records with the data collected from newspaper articles.

Figure 5.

Photocopy of Register of the Deaths, with the name of late Matija Sentić.

Figure 6.

Photocopy of Register of the Deaths, with the name of late Bartul Crnčević.

Two members of the Sentić family were affected by the leprosy. Ivan Sentić was a sailor, who was most likely infected during his journey to China. He was persistent in refusing to stay in the leprosarium. His mother was also affected by the disease, while her second son Bartul stayed with them although he was not ill, and he later emigrated to the USA (22). The name of Ivan Sentić can be found in the Neumann’s memorandum about the health conditions in Dalmatia in 1906, addressed to the Prime Minister (25).

At the same time, Radovan Jerković, a priest from the lower Neretva region also wrote about the recently opened leprosarium, mentioning the name of Matija Milinković, a leper from the village of Vidonje, who was isolated in the leprosarium, accompanied by her healthy mother. He also mentioned two persons with the surname Ilić, a sick daughter and her healthy mother, who came later to the leprosarium from the island of Vis (26). Peričić wrote, without mentioning the name, about a leper from the village of Vidonje who escaped from Metković because he could not stand the isolation any more. He came to Zadar in 1904 to make a complaint to the authorities but he was of course immediately arrested (10).

Leprosarium was active until 1925 when, after the gradual natural decrease in the number of isolates, it was closed and the rest of the patients were transferred to the leprosarium of the country hospital in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

After the last lepers left, the building was disinfected. The Inspectorate of the National Ministry of Health in Split gave the complex to the Metković district for the isolation of acute infectious diseases. At first, the government of Metković district made a firm commitment to convert the leprosarium into a “solitary place” for isolation of the acutely ill, but unfortunately the estimated expenses were too high for the local authorities, so they gave up the contract (19).

After that, the complex was neglected and left to slowly dilapidate. After the closing of the leprosarium, no single case of leprosy was documented, so it could be concluded that in 1925 leprosy was eradicated in southern Croatia. Today as a reminder of the last leprosarium in Croatia, we have only the ruins surrounded with the dense vegetation and the toponym “Lepers’ houses,” well rooted in the local population (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Remains of the “Lepers’ houses.”

Discussion

The last leprosarium in south Croatia served as the starting point for our study of leprosy in south of Croatia at the beginning of the 20th century. It also confirmed the usual pattern of behavior towards this disease, which was firmly rooted in the minds of people ever since the medieval times. Leprosarium, with its local name “Lepers’ houses,” built in Metković in 1905, tells us much about the perception of leprosy, the isolation and fear of the infection, regular presence of the local priest, and almost formal need for medical care. On the other hand, rapid development of bacteriology at that time gradually changed the view on lepers' isolation. Still there was some insecurity about a differential diagnosis of leprosy, as can be seen in the case of Mal de Meleda, which was sometimes misdiagnosed as leprosy (11). As Peričić noticed in 1937 (10), the role of medical profession, although present much stronger than before, was confined to the identification of the diseased, according to the knowledge of the clinical picture and isolation.

At the end of the 19th century, the strongest supporter of the isolation of lepers was Isidor Neumann (1832-1906) who, as an authorized expert, visited Dalmatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina on three separate occasions. In his Memorandum addressed to the Prime-minister in 1906, he warned the authorities, with high concern, on the endemic loci of leprosy in Dalmatia. He urged that military doctors should control civil ones for effective documentation and isolation of all infectious diseases. The isolation should be in one place, and the government should guarantee the support for the families from which the main family provider was removed (25). In the case of the Metković leprosarium, the main role of medical practitioners was in organizing and founding the institution, while their role in the medical treatment of the isolates was not recorded, since it could not have been of great importance in the times when specific therapy has not yet been discovered.

References

- 1.Rea HT, Modlin LR. Leprosy. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI. Fitzpatrick′s dermatology in general medicine, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2003. p. 2306. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winkle S. Cultural history of plagues[in German]. Dusseldorf/Zurich: Artemis and Winkler; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yens DA, Asters DJ, Teitel A. Subcutaneous nodules and joint deformity in leprosy; case report and review. J Clin Rheumatol. 2003;9:181–6. doi: 10.1097/01.RHU.0000073593.65503.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grmek MD. Leprosy [in Croatian]. In: Medicinska enciklopedija vol 4 Zagreb: Leksikografski zavod; 1968. p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prastalo Z. Leprosy of respiratory tract (lecture on the 1. ENT congress) Lijec Vjesn. 1932;54:12. [in Croatian]. - [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonetic N. Cases of leprosy in Hrvatsko Primorje. Lijec Vjesn. 1931;53:789–92. [in Croatian]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fatovic-Ferencic S, Buklijas T. The image of a leper (?): a paradigm of hidden fears of contagious diseases (exemplified in a wall painting of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:447–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vukas A. The leper focus in one village on Krk island. Lijec Vjesn. 1940;62:259–60. [in Croatian]. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cajkovac J. Lepra tuberoanaesteica. Lijec Vjesn. 1939;61:315–17. [in Croatian]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pericic B. About one leper focus in the Middle Dalmatia. Lijec Vjesn. 1937;62:264–6. [in Croatian]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fatovic-Ferencic S, Holubar K. Mal de Meleda: from legend to reality. Dermatology. 2001;203:7–13. doi: 10.1159/000051695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanimirovic A, Skerlev M, Gacina P, Beck T, Stipic T, Basta-Juzbasic A. Leprosy in Croatia in the twentieth century. Lepr Rev. 1995;66:318–23. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19950036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fortis A. Traveling through Dalmatia [in Croatian]. Split: Marjan Tisak; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masic I. Development of health care services in Bosnia-Herzegovina during the Ottoman empire. Med Arh. 1991;45:127–32. [In Croatian]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masic I. The first hospital facilities in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Med Arh. 2004;58:127–32. [in Croatian]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arslanagic-Mutevelic N. 100 years of dermatovenereology in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Med Arh. 1994;48:197–200. [in Croatian]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grujic M. Development of internal medicine since the establishment of the Regional Hospital in Sarajevo from 1894 until today. Med Arh. 1994;48:183–5. [in Croatian]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konjhodzic F. From the regional hospital to the Clinical Center in Sarajevo – 100 years of work and development. Med Arh. 1994;48:163–6. [in Croatian]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juric I. The economic and merchant development of the harbour of Metković 1850-1918 [in Croatian]. Metković: Matica hrvatska; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leprosarium [in Croatian]. Smotra Dalmatinska. 1905 Apr 1; Sect. Dalmatinske vijesti (col. 3 and 4).

- 21.Sirovica S. The last protomedic of Dalmatia during Austro-Hungary Monarchy Dr. Karl Vipauc [in Croatian]. Šibenik: Štampa; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The leprouses [in Croatian]. Narodni list. 1905 Mar 29; p. 3. (col. 2).

- 23.The register of the Roman Catholic parish of Metković – the book of deceased (1902-1923) [in Croatian]. volume 7, p. 178.

- 24.The register of parish of Vidonje (1917) [in Croatian]. p. 104.

- 25.Neumann J. Memorandum. Lijec Vjesn. 1930;32:132–8. [in German]. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vidovic M. Rev. Radovan Jerkovic – life and work [in Croatian]. Metković: Matica hrvatska; 2000. [Google Scholar]