Abstract

Aim

To assess whether alterations in the K-ras, p53, and DPC4 genes are present in pancreatitis, a potential precancerous condition that can progress to pancreatic adenocarcinoma. To investigate the alterations occurring at hot spots of K-ras (exon 1), p53 (exons 5 and 7), and DPC4 (exons 8, 10 and 11).

Methods

In 10 patients with acute and 22 with chronic pancreatitis, without pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN), DNA was isolated from paraffin embedded tissue samples. The extracted DNA was analyzed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis, and DNA sequencing.

Results

In acute pancreatitis samples no mutations were found in any of the investigated genes. In 7 out of 22 samples of chronic pancreatitis nucleotide substitution at exon 1 of K-ras (five at codon 12 and two at codon 13) were found. No mutations in p53 (exons 5 and 7) were detected. Two samples had nucleotide substitutions at exons 8 and 11 of DPC4, introducing STOP signal and change in the amino acid sequence, respectively. One chronic pancreatitis sample displayed simultaneous mutations in K-ras (exon 1, codon 12) and DPC4 (exon 8, codon 358).

Conclusion

Mutations of K-ras and Dpc4 genes can accumulate already in non-malignant, inflammatory pancreatic tissue, suggesting its applicability in monitoring of further destruction of pancreatic tissue and progression into malignancy.

Pancreatitis is an inflammatory disease of the pancreas, characterized by the progressive tissue destruction, leading both to exocrine and endocrine insufficiency. Acute pancreatitis can manifest as a benign condition with minimal abdominal pain and hyperamylasemia, or can have a fulminate course due to the development of infective pancreatic necrosis and multisystem organ failure (1).

On the other hand, chronic pancreatitis is characterized by the progressive destruction of pancreatic parenchyma and its replacement by variable amounts of fibrous tissue (2). A characteristic histological profile displays a fibrosis in association with the foci of inflammatory cells, the regions of acinar cell degradation, and the areas of ductal cell proliferation (3).

Diagnosing pancreatitis at an early stage is a clinical challenge, because the frequency of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in patients with pre-existing chronic pancreatitis is significantly higher than in the general population. It has been shown that chronic pancreatitis increases the risk of developing pancreatic cancer 10 to 20 times (4). Progression model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma at the molecular level shows that it always harbors K-ras, p53, and p16 alterations, and also mutations in the DPC4 (deleted in pancreatic cancer gene, locus 4) (5-7). In contrast to pancreatic cancer, the molecular mechanism responsible for acute and chronic pancreatitis is poorly understood. Some improvement has been made with the discovery of the genetic nature of hereditary pancreatitis (8,9). The studies of molecular alterations occurring in acute and chronic pancreatitis have mainly included the investigation of alterations in cationic trypsinogen gene, K-ras, p53, or cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene (CFTR) (8,10-14).

Since pancreatitis represents a precancerous state in a considerable number of cases, we assumed that the alterations in more than one gene could be associated with the genetic basis of the disease and the genes involved in the development of pancreatic adenocarcinoma could be mutated already in pancreatitis. Therefore, in collected tissue samples of acute and chronic pancreatitis, we investigated the alterations occurring at hot spots of three different genes (K-ras, p53, DPC4) which are members of different signaling pathways.

Material and methods

Patients and genomic DNA preparation

Postmortem pancreatitis samples were obtained from 10 patients with acute pancreatitis and 22 patients with chronic pancreatitis between 1998 and 2003. For the purposes of this study, the samples were retrieved from the archival tissue files of the Zagreb University Hospital Center, Department of Pathology. Histological sections cut from 10% buffered formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks were routinely stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Diagnosis of acute and chronic pancreatitis without pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) was confirmed by the same pathologist (J. J. R.) for all samples.

Paraffin-embedded sections (4 µm) were fixed to the slides, and 2-3 sections were used for one-step DNA extraction by TaKaRa DEXPAT TM (TaKaRa Bio Europe, Inc, Gennevilliers, France) according to manufacturer's instructions. Three separate DNA extracts were prepared from each paraffin embedded block.

Polymerase chain reactions

Genomic DNA from the sections was amplified by polymerase chain reactions (PCR) in a final reaction volume of 25 µL containing lx HotMaster Taq Buffer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), 50 µmol/L of each dNTP (Eppendorf), 5 pmol of forward and reverse primers, 1 U HotMaster Taq DNA polymerase (Eppendorf), and 2.5 µL of extracted DNA (50-100 ng).

PCR was performed under conditions of an initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 minutes, 30-40 cycles consisted of denaturation (30 seconds at 94°C), annealing (30 seconds at 51-58°C, depending on the primer) and elongation step (30 seconds at 72°C), and a final extension step at 72°C for 7 minutes. Reactions were performed in a BioSystems Thermocycler 2700 (Applied BioSystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Each PCR batch was tested three times and always included a blank to which no DNA had been added, to ensure that no contamination of samples had occurred. Sequences of primers designed for PCR reaction are listed in Table 1. The PCR products were visualized in ethidium bromide-stained 3% agarose gel.

Table 1.

Mutational analysis of three genes in 22 chronic pancreatitis tissue samples

| Gene | Codon | Primer sequences |

No. of mutated samples | Type of mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 8→3 8 | ||||

|

K-ras |

12 |

ACTGAATATAAACTTGTGGTAGTTGGACCT, TCAAAGAATGGTCCTGGACC, TAATATGTCGACTAAAACAAGATTTACCTC |

5 |

GGT>GAT, TGT, GTT, GCT or GAT |

|

K-ras |

13 |

ACTGAATATAAACTTGTGGTAGTTGGCCCTGGT, ACTCATGAAAATGGTCAGAGAACCTTTAT, TCAAAGAATGGTCCTGCACC |

2 |

GGC>GAC,TGC or GAC |

|

p53 |

175 |

TGTTCACTTGTGCCCTGACT, CAGCCCTGTCGTCTCTCC |

0 |

- |

|

p53 |

248 |

CCTCATCTTGGGCCTGT, CCAGGGGTCAGCGGCAAGCA |

0 |

- |

|

DPC4 |

358 |

CTCCTGAGTATTGGTGTTCC, CTTGCTCTCTCAATGGCTTC |

1* |

c.1203G>T |

|

DPC4 |

412 |

TTGCGTCAGTGTCATCGACAA, GATAGCTGGAGCTATTCCAC |

0 |

- |

| DPC4 | 539 | TCTGTCAGCTGCTGCTGGAA, GGTTGTGGGTCTGCAATCGG | 1 | c.1744T>G |

*Sample also positive to K-ras/12 mutation.

All pancreatitis samples were screened for mutation within coding region by two analyses: PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (RFLP) for detection of previously documented mutation based on restriction site, and PCR-single strand conformation polymorphism analysis (SSCP) for searching for other mutations in the analyzed samples.

PCR-RFLP

PCR-RFLP analysis was used in order to detect mutations in the hot spots of K-ras (codons 12 and 13), p53 (codons 175 and 248), and DPC4 (codons 358, 412, and 493) genes.

Two PCR amplification rounds were performed for mutational analysis at exon 1 of the K-ras gene (15). PCR products were digested with Bst NI (New England BioLabs Inc., Frankfurt, Germany) for testing mutation at codon 12, and with Bgl I (BioLabs) for revealing mutation at codon 13, under the reaction conditions recommended by the supplier.

p53 mutations were identified using PCR amplification, followed by restriction with Cfo (BioLabs) enzyme (exon 5, codon 175), and with MspI (BioLabs) enzyme (exon 7, codon 248).

The screen for mutation in the DPC4 gene involved exons 8 (codon 358), 10 (codon 412), and 11 (codon 493), under the same conditions as published in our previous study (16).

RFLP products of analyzed genes were separated on Spreadex EL 300 or EL 400 gels (Elchrom Scientific, Cham, Switzerland). A 6 µL of restriction mixture, together with 1 µL of loading buffer (Eppendorf) were loaded onto gel, which was subsequently stained with Sybr Gold (Molecular Probes, Leiden, Netherlands) for 30 minutes, destained in distilled water, and analyzed on UV transilluminator at 254 nm.

PCR-SSCP

All specimens of pancreatitis tissue were screened for other mutations within the coding region of K-ras (exon 1), p53 (exons 5 and 7), and DPC4 (exons 8, 10 and 11) by PCR-SSCP analysis.

A 5 µL of PCR product was mixed with 7 µL of formamide with 10 mmol/L NaOH. The mixture was heated at 95°C for 5 minutes and then immediately placed on ice. Samples were separated by electrophoresis in 8% polyacrylamide gels at +4°C. The gels were silver stained.

Sequence analysis of PCR products

PCR product of the sample which revealed aberrant PCR-SSCP pattern was directly re-amplified from the Spreadex EL 1200 gel and then purified using a QIAquick column (QIAGEN Companies, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One microgram of purified PCR product in volume of 50 µL was sequenced by ABI PRISM Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction FS Kit and an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Results

K-ras

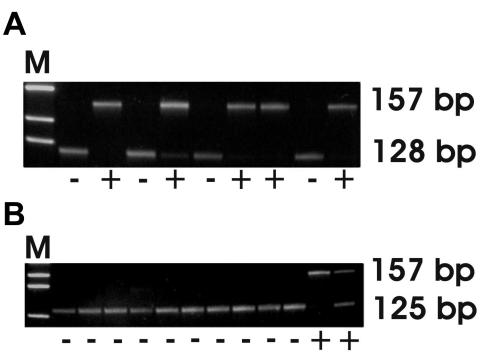

PCR-RFLP analysis of exon 1 of the K-ras showed nucleotide substitution at codon 12 in 5 samples (Figure 1A) and at codon 13 in 2 samples of chronic pancreatitis (Figure 1B). One sample with mutation at codon 12 of K-ras was also positive to DPC4 mutation (Table 1). None of the samples had patterns showing aberrant SSCP variants.

Figure 1.

K-ras gene profile (exon 1) of chronic pancreatitis samples after RFLP analysis. A, 157 bp fragment represents mutation (+) at codon 12 and 128 bp fragment represents wild type allele (-). B, 157 bp fragment represents mutation (+) at codon 13 and 125 bp fragment represents wild type (-) allele. M – molecular weight DNA marker IX (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany).

p53

PCR-RFLP analysis of the p53 gene revealed no mutations at exon 5 (codon 175) and exon 7 (codon 248) in all 32 pancreatitis samples (Table 1). Moreover, no aberrant profile in PCR-SSCP analysis of these samples was detected.

DPC4

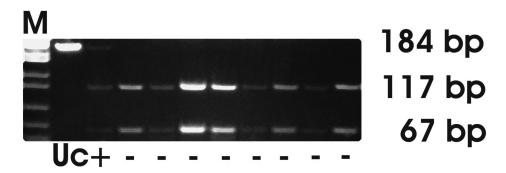

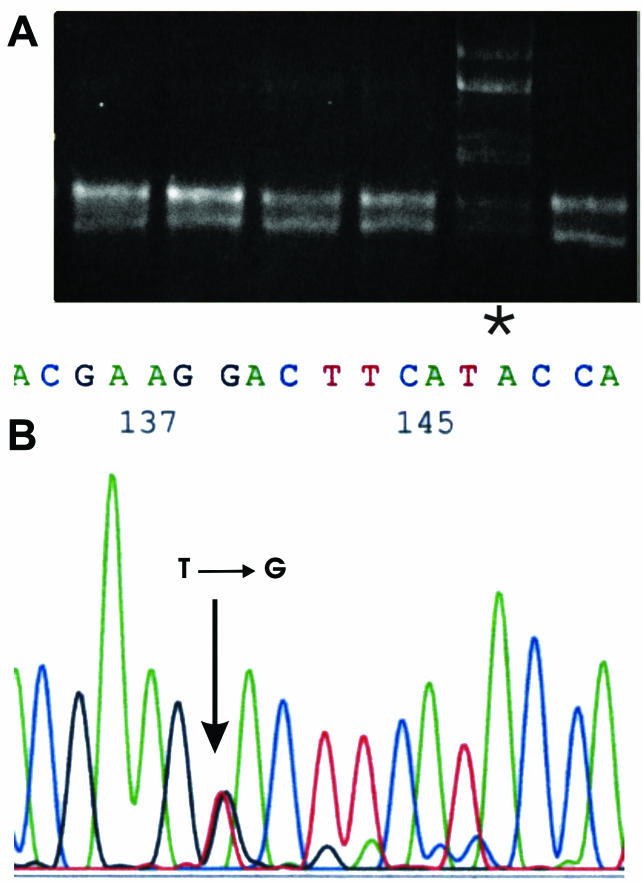

A single chronic pancreatitis sample showed the nucleotide substitution GGA→TGA, introducing STOP signal instead of Gly at exon 8 (Figure 2). The same sample also had a mutation at codon 12 of the K-ras gene (Table 1). Additional PCR-SSCP analysis of DPC4 indicated the presence of a mutation in another sample of chronic pancreatitis (Figure 3A). Sequence analysis confirmed that indication, revealing GTA→GGA substitution at exon 11 (codon 539) which causes a change in the amino acid sequence (Val→Gly) (Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

DPC4 gene profile (exon 8) of chronic pancreatitis samples after RFLP analysis. Mutant allele (+) lacks Mnl l restriction site at codon 358, resulting with 184 bp fragment and wild type allele (-) is cut by Mnl l at codon 358 resulting with 117 bp and 67 bp fragments. M – molecular weight DNA marker M3 (Elchrom Scientific); uc – uncut PCR product.

Figure 3.

DPC4 gene mutation (exon 11) in one chronic pancreatitis sample. A, PCR-SSCP analysis of the DNA fragment (asterisk indicates abberant SSCP pattern). B, Sequence analysis of the same DNA fragment points out single nucleotide substitution at codon 539.

Discussion

This study presents the evidence of alterations in K-ras and DPC4 genes, but not in p53 gene, in paraffin embedded tissue samples of chronic pancreatitis. Inflammation within the pancreatic ducts could cause alterations in numerous genes that belong to different pathways (17). We speculate that the mutations we observed could be involved in malignant transformation and therefore mark pre-malignant pancreatic state.

The analysis performed on acute pancreatitis samples showed the absence of mutations at any analyzed locus of all tested genes. This finding is consistent with the fact that most cases of acute pancreatitis recover without long-term sequel, with only a minority of cases progressing to chronic pancreatitis (1,18,19). The time to accumulate mutations due to inflammation is thus shortened, and cells are destroyed rather than altered.

Of all genes tested in this study, K-ras exhibited the highest frequency of mutations in chronic pancreatitis samples; 5 samples (23%) were positive in the codon 12 and 2 (9%) in the codon 13. These results were not unexpected because the presence of K-ras mutation is not rare in patients with chronic pancreatitis, as validated by several groups, which found K-ras mutations in 39% (20), 28% (21), or 34% (22) of patients with chronic pancreatitis. These data indicate that K-ras alterations could be taken as a risk factor for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, although the sequence of events and the time required for conversion to an established malignancy is very hard to define. In contrast to our results, two groups came to the conclusion that this mutation is exceedingly uncommon within the paraffin-embedded pancreatitis specimens. They demonstrated the total absence of K-ras (codons 12 and 13) mutations in samples of chronic pancreatitis (2,12).

Furthermore, we also analyzed the p53 gene at mutational hot spots, exon 5 and 7. No p53 gene mutations were discovered in the analyzed pancreatitis samples, which is consistent with prior observations that these mutations occur in chronic pancreatitis tissues only occasionally (11,23), in contrast to pancreatic carcinomas, where the occurrence is almost 50% (23-25). On the other hand, our results are in opposition to those obtained by one research group (12) presenting the evidence for early occurrence of p53 (exons 5-9) mutations in chronic pancreatitis. Eight of 80 samples displayed alterations in p53 detected by PCR-SSCP analysis and confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. The authors suggested that mutations in p53 could also occur at an early stage of pancreatic disease, without morphological evidence of pancreatic cancer, as has been found in benign or precancerous lesions in other human tissues, such as hyperplastic prostatic epithelium (26) and fibroadenoma of the breast (27). The accumulated data suggest that we should continue to investigate some additional exons of p53 in a larger series of patients with chronic pancreatitis.

In this study, we also focused on the DPC4 gene, whose protein mediates signals from the family of ligands of transforming growth factor-β signaling pathway (28). In 2 of 22 examined samples, mutations in C-terminal region of DPC4 were found. One sample revealed nucleotide substitution at codon 358 (exon 8) which is incorporated into the mutation cluster region of the gene (29), and another sample had a single nucleotide substitution at codon 539 (exon 11). This is an interesting finding because previous molecular studies showed that inactivating mutation of the DPC4 gene is a late genetic change in the multistep progression model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas contributing to tumor progression (30-33). Mutations occurring at the exons of DPC4 gene have never been found in pancreatitis tissues. One chronic pancreatitis sample in our study displayed simultaneous mutations in K-ras (codon 12) and DPC4 (exon 8) genes. To our knowledge, only one group detected coinciding alterations of K-ras and DPC4 genes in non-tumoral pancreatic disease (34). But in that study, pancreatic juice of patients with chronic pancreatitis was sampled and only codon 12 of K-ras was analyzed.

Our study demonstrated that DPC4 mutations might be present already in non-malignant tissue such as that of chronic pancreatitis, which is considered to have a potential for malignant transformation. The significance of these mutations and their consequences should be clarified in the future. Nevertheless, the finding of mutated DPC4 in chronic pancreatitis suggests an involvement of mutation in the progression of the disease toward malignancy.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the Croatian Ministry for Sciences and Technology; grants No. 098-0982464-2460 and 098-0982464-2508. The authors thank Ms Marina Marš for excellent technical assistance.

References

- 1.Bradley EL., III A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, GA, USA. September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg. 1993;128:586–90. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420170122019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsiang D, Friess H, Buchler MW, Ebert M, Butler J, Korc M. Absence of K-ras mutations in the pancreatic parenchyma of patients with chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1997;173:242–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiMagno MJ, DiMagno EP. Chronic pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2004;20:444–51. doi: 10.1097/00001574-200409000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrow B, Sugiyama Y, Chen A, Uffort E, Nealon W, Mark Evers B. Inflammatory mechanisms contributing to pancreatic cancer development. Ann Surg. 2004;239:763–9. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000128681.76786.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hruban RH, Goggins M, Parsons J, Kern SE. Progression model for pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2969–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowgill SM, Muscarella P. The genetics of pancreatic cancer. Am J Surg. 2003;186:279–86. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(03)00226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maitra A, Adsay NV, Argani P, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, De Marzo A, Cameron JL, et al. Multicomponent analysis of the pancreatic adenocarcinoma progression model using a pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia tissue microarray. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:902–12. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000086072.56290.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitcomb DC, Gorry MC, Preston RA, Furey W, Sossenheimer MJ, Ulrich CD, et al. Hereditary pancreatitis is caused by a mutation in the cationic trypsinogen gene. Nat Genet. 1996;14:141–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitcomb DC, Somogyi L. Lessons from hereditary pancreatitis. Croat Med J. 2001;42:484–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kubrusly MS, Cunha JE, Bacchella T, Abdo EE, Jukemura J, Penteado S, et al. Detection of K-ras point mutation at codon 12 in pancreatic diseases: a study in a Brazilian casuistic. JOP. 2002;3:144–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casey G, Yamanaka Y, Friess H, Kobrin MS, Lopez ME, Buchler M, et al. p53 mutations are common in pancreatic cancer and are absent in chronic pancreatitis. Cancer Lett. 1993;69:151–60. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(93)90168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gansauge S, Schmid RM, Muller J, Adler G, Mattfeldt T, Beger HG. Genetic alterations in chronic pancreatitis: evidence for early occurrence of p53 but not K-ras mutations. Br J Surg. 1998;85:337–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luttges J, Diederichs A, Menke MA, Vogel I, Kremer B, Kloppel G. Ductal lesions in patients with chronic pancreatitis show K-ras mutations in a frequency similar to that in the normal pancreas and lack nuclear immunoreactivity for p53. Cancer. 2000;88:2495–504. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000601)88:11<2495::aid-cncr10>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choudari CP, Imperiale TF, Sherman S, Fogel E, Lehman GA. Risk of pancreatitis with mutation of the cystic fibrosis gene. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1358–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nollau P, Moser C, Weinland G, Wagener C. Detection of K-ras mutations in stools of patients with colorectal cancer by mutant-enriched PCR. Int J Cancer. 1996;66:332–6. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960503)66:3<332::AID-IJC11>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popovic Hadzija M, Radosevic S, Kovacevic D, Lukac J, Hadzija M, Spaventi R, et al. Status of the DPC4 tumor suppressor gene in sporadic colon adenocarcinoma of Croatian patients: identification of a novel somatic mutation. Mutat Res. 2004;548:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss FU, Simon P, Mayerle J, Kraft M, Lerch MM. Germline mutations and gene polymorphism associated with human pancreatitis. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2006;35:289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberg W, Tenner S. Acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1198–208. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404283301706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balthazar EJ. Acute pancreatitis: assessment of severity with clinical and CT evaluation. Radiology. 2002;223:603–13. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2233010680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arvanitakis M, Van Laethem JL, Parma J, De Maertelaer V, Delhaye M, Deviere J. Predictive factors for pancreatic cancer in patients with chronic pancreatitis in association with K-ras gene mutation. Endoscopy. 2004;36:535–42. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Queneau PE, Adessi GL, Thibault P, Cleau D, Heyd B, Mantion G, et al. Early detection of pancreatic cancer in patients with chronic pancreatitis: diagnostic utility of a K-ras point mutation in the pancreatic juice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:700–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan L, McFaul C, Howes N, Leslie J, Lancaster G, Wong T, et al. Molecular analysis to detect pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in high-risk groups. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:2124–30. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Talar-Wojnarowska R, Gasiorowska A, Smolarz B, Romanowicz-Makowskal H, Strzelczyk J, Janiak A, et al. Comparative evaluation of p53 mutation in pancreatic adenocarcinoma and chronic pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:608–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scarpa A, Capelli P, Mukai K, Zamboni G, Oda T, Iacono C, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinomas frequently show p53 gene mutations. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:1534–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rozenblum E, Schutte M, Goggins M, Hahn SA, Panzer S, Zahurak M, et al. Tumor-suppressive pathways in pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1731–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kallakury BV, Jennings TA, Ross JS, Breese K, Figge HL, Fisher HA, et al. Alteration of the p53 locus in benign hyperplastic prostatic epithelium associated with high-grade prostatic adenocarcinoma. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1994;3:227–32. doi: 10.1097/00019606-199412000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millikan R, Hulka B, Thor A, Zhang Y, Edgerton S, Zhang X, et al. p53 mutations in benign breast tissue. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2293–300. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.9.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–84. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Song J, Parmiagiani G, Yeo CJ, Hruban RH, Kern SE. Missense mutations of MADH4: characterization of the mutational hot spot and functional consequences in human tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1597–604. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilentz RE, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Argani P, McCarthy DM, Parsons JL, Yeo CJ, et al. Loss of expression of Dpc4 in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: evidence that DPC4 inactivation occurs late in neoplastic progression. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2002–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inoue H, Furukawa T, Sunamura M, Takeda K, Matsuno S, Horii A. Exclusion of SMAD4 mutation as an early genetic change in human pancreatic ductal tumorigenesis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2001;31:295–9. doi: 10.1002/gcc.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luttges J, Galehdari H, Brocker V, Schwarte-Waldhoff I, Henne-Bruns D, Kloppel G, et al. Allelic loss is often the first hit in the biallelic inactivation of the p53 and DPC4 genes during pancreatic carcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1677–83. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64123-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Del Chiaro M, Boggi U, Presciuttini S, Bertacca L, Croce C, Mosca I, et al. Genetics of pancreatic cancer: where are we now? Where are we going? JOP. 2005;6(1) Suppl:60–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costentin L, Pages P, Bouisson M, Berthelemy P, Buscail L, Escourrou J, et al. Frequent deletions of tumor suppressor genes in pure pancreatic juice from patients with tumoral or nontumoral pancreatic diseases. Pancreatology. 2002;2:17–25. doi: 10.1159/000049443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]