Abstract

Age-related changes in carbonylation of mitochondrial proteins were determined in mitochondria from the flight muscles of Drosophila melanogaster. Reactivity with antibodies against (i) adducts of dinitrophenyl hydrazone (DNP), commonly assumed to react broadly with derivatized carbonyl groups, (ii) malondialdehyde (MDA) or (iii) hydroxynonenal (HNE), was compared at five different ages of flies. MDA and HNE are carbonyl-containing products of lipid peroxidation, which can form covalent adducts with proteins. Specific objectives were to address the following inter-related issues: (1) what are the sources of adducts involved in protein carbonylation in mitochondria during aging; (2) is carbonylation by different adducts detectable solely by the DNP antibodies, as assumed widely; (3) can the adducts formed by lipid peroxidation products in vivo, be used as markers for monitoring age-associated changes in oxidative damage to proteins. The total amounts of immunoreactive proteins, detected by all three antibodies, were found to increase with age; however, the immunodensity of individual reactive bands and the magnitude of the increases were variable, and unrelated to the relative abundance of a protein. While some protein bands were strongly immunopositive for all three antibodies, others were quite selective. The amounts of high molecular weight cross-linked proteins (>200 kDa) increased with age. In general, the anti-HNE antibody reacted with more protein bands compared to the anti-MDA or -DNP antibody. The results suggest that sources of the carbonyl-containing protein adducts vary and no single antibody reacts with all of them. Overall, the results indicate that HNE shows robust age-associated increases in adductation with mitochondrial proteins, and is a good marker for monitoring protein oxidative damage during aging.

Keywords: Carbonylation, hydroxynonenal, malondialdehyde, oxidative stress, aging, Drosophila melanogaster, antibodies

INTRODUCTION

A primary manifestation of the aging process is the progressive loss in the functional competence of various physiological systems, which diminishes the ability to maintain homeostasis, with a consequent exponential rise in the rate of mortality [1, 2]. Although a cause-and-effect relationship has yet to be firmly established, a pro-oxidizing shift in the cellular redox state and progressive accumulation of macromolecular oxidative damage, are often postulated to underlie the age-associated attrition in the maximal capacity of physiological systems (reviewed in [3–6]). Mitochondria are often implicated in the causation of oxidative stress and senescent changes because: (i) their inner membrane is the primary site of generation of superoxide anion radical, a progenitor of an array of downstream reactive oxygen species (ROS) [7, 8]; (ii) mitochondrial respiratory activity, particularly the ADP-stimulated state 3 rate of oxygen consumption, declines in the aged organisms [9, 10]; and (iii) mitochondria themselves undergo an age-associated increase in macromolecular oxidative damage, which has been experimentally demonstrated to lead to an increase in rates of mitochondrial ROS generation [11] and a decline in respiratory activity [12].

Although virtually all types of macromolecules undergo oxidative damage in vivo, protein damage is thought to have direct physiological consequences due to their role as bio-catalysts. Attacks by ROS on proteins can cause a variety of structural modifications including, formation of disulfide cross-links, methionine sulfoxide, dityrosine cross-links, nitrotyrosine, and carbonyls [3, 13]. The addition of carbonyl groups is a ubiquitous and well-characterized post-translational modification. Protein carbonylation can occur by at least three different mechanisms (reviewed in [3, 14, 15]): (i) metal-catalyzed oxidation (MCO), which introduces carbonyls in to the side-chains of certain amino acids; (ii) reactions with lipid peroxidation products containing aldehyde functional groups, such as HNE and MDA, and (iii) interaction between glycine residues and sugars (glycation) or their oxidation products (glycoxidation). Membrane proteins are thought to be particularly susceptible to modification by the products of lipid peroxidation, because of the presence of the polyunsaturated fatty acids in the phospholipid bilayer, whereas glycation tends to be largely restricted to the extracellular proteins [16].

It is now well established that the amount of carbonylated protein in tissue homogenates of different species increases during aging [15, 17]. In initial studies, where amounts of protein carbonyls, derivatized with DNPH, were measured spectrophotometrically, it was estimated that >10% of the protein in tissue homogenates of aged organisms was carbonylated [3]. It was also inferred from such data that carbonylation was a ubiquitous and random process. However, later studies, initially conducted in this laboratory, involving immunoblotting with anti-DNP antibodies, indicated that protein carbonylation during aging largely targets specific proteins and is not a random occurrence [18, 19]. Since carbonylation can potentially affect protein catalytic activity, it is of interest to understand the mechanisms of carbonylation, particularly the intracellular sources of the carbonyl adducts, e.g. whether they are formed by MCO or are products of lipid peroxidation, such as MDA and HNE. This issue is also of practical importance as it is presently unclear whether anti-DNP antibody, which is most commonly used for the localization of carbonylated proteins is indeed versatile and specific enough to react with different carbonyl-containing epitopes, including MDA and HNE.

Another important issue concerning anti-DNP antibodies is that their use for quantification of carbonylated proteins has been widely reported to yield erratic results. For instance, while some studies have found aging-related increases in protein carbonyl content [4, 11, 17], others reported the absence of such increases (e.g. see [20] and references therein). Some of the reported limitations of this technique include artifactual formation of carbonyls during tissue handling, batch-to-batch variation in specificity of commercially available antibodies and alterations in the electrophoretic and electrofocusing mobility of DNPH-derivatized proteins compared to underivatized samples. Such variations can complicate quantitative comparisons between immunoblots. The reliability of the DNP-based carbonyl assays has been repeatedly questioned and caution advised in the interpretation of data [21]. Accordingly, in this study the patterns of protein carbonylation were investigated in mitochondria from the flight muscles of Drosophila melanogaster at different ages, using antibodies against DNP, MDA or HNE. The main aim was to compare the different immunoprobes to localize carbonylated proteins in mitochondria during aging.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Chemicals

Sources of the various chemicals were: 2,4-Dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH), Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO); anti-HNE antibodies, Alpha Diagnostics (San Antonio, TX); anti-MDA antibodies, Academy Bio-Medical Company Inc., (Houston, TX); anti-porin antibodies, Mitosciences (Eugene, OR); polyclonal rabbit anti-dinitrophenyl (DNP) antibodies, Zymed (San Francisco, CA); ECL plus Western blotting detection system, Amersham Biosciences, (Arlington Heights, IL); horse radish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies, Pierce (Rockford, IL). All other chemicals used were of the highest purity available commercially.

Animals

Larvae of y w Drosophila melanogaster were raised on a standard mixture of agar, cornmeal, and yeast as described previously [22]. After eclosion, flies were anaesthetized with a gentle stream of CO2, and grouped in batches of twenty-five. They were subsequently maintained at 25°C under constant light. Studies were conducted on male flies.

Isolation of mitochondria and detection of DPN, HNE and MDA modified proteins

Mitochondria were isolated from thoracic flight muscles, as described previously [10, 22]. Briefly, thoraces from 200 flies were excised using a razor blade and gently pounded in a chilled mortar, containing 300–400 μl of ice-cold isolation buffer (0.32M sucrose, 10 mM EDTA and 10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.3), to which 2% (w/v) BSA (fatty acid content 0.003%) had been added. The brei was filtered through Spectra/Mesh® nylon (pore size=10μm). After centrifugation for 10 min at 2200 g, the pellet was rinsed briefly in BSA-free isolation buffer, resuspended in 500 μl of the BSA-free buffer and stored at −80°C until used.

To detect protein carbonyls (C=O) immunochemically with anti-DNP antibodies, mitochondrial samples were treated with dinitrophenyl hydrazine (DNPH) according to the methods of Levine [23] and resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% v/v), as described by Laemmli [24], and transferred onto PVDF membrane at 4°C overnight. The blots were then incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-DNP antibodies, diluted at 1:5,000 in TBS-T containing 5% fat-free milk. The membranes were subsequently treated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies at 1:10,000 dilution in TBS-T overnight at 4°C. Immunostained proteins were visualized using ECL-Plus Western blotting detection reagent. HNE and MDA blots were processed identically but without the DNPH derivatization. Following SDS–PAGE separation, gels were stained with Coomassie to visualize total protein loading onto the gels. The amount of protein in a specific band was quantified densitometrically on dried SDS–PAGE gels. Total protein amounts were determined prior to gel loading using the sodium BCA (bicinchoninic acid) protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL), according to the manufacturers instructions. Band intensity data were statistically analyzed by pair-wise comparisons to the youngest samples by Student’s t-tests on Microsoft Excel 2002 software. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Immunoblotting controls

Anti-porin monoclonal antibodies (Mitosciences, Eugene, OR), at a concentration of 1:10000, were always used to check protein loading and blotting. Primary and secondary antibodies were tested for specificity with immuno-blots performed in the presence or absence of each antibody.

RESULTS

Life spans of the y w flies under conditions similar to those in this study have been reported previously (e.g. see [25], amongst many others). Typically, the average life span is about 70 days and the maximum around 100 days. Samples were taken from flies ranging from 15 to 60 days of age.

Comparison of protein amounts at different ages

Initially, aliquots of flight muscle mitochondrial proteins from 15-, 22-, 30-, 45- and 60-day-old-flies were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie in order to ascertain whether the levels of proteins, indicated by densities of the various bands, were altered during aging (Fig. 1). Although the separation by SDS-PAGE cannot adequately resolve the low-abundance proteins, information about the potential age-related changes in the densities of the readily visible bands is deemed essential for the comparisons of western blots at different ages. Nonetheless, no notable age-related differences in the densities of protein bands in Coomassie stained gels were apparent (Fig. 1A).

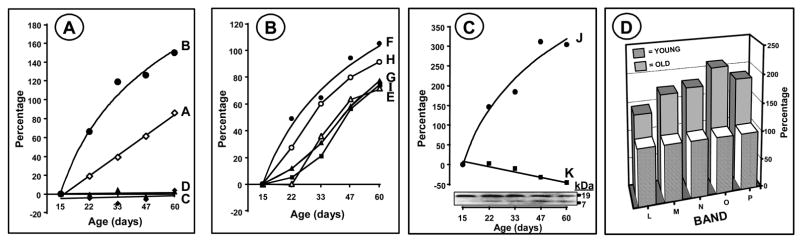

Figure 1. Immunological determination of MDA-, HNE- and DNP-modified mitochondrial proteins from the flight muscles Drosophila melanogaster (15-, 22-, 30-, 45- and 60-day-old-flies).

DNPH treated total mitochondrial proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto PVDF membrane. HNE-and MDA-modified proteins were detected immunochemically, as described in Materials and Methods. Panel A shows Coomassie stained proteins; Panel B, immunolabelling with anti-MDA proteins; Panel C, immunolabelling with anti-HNE proteins Panel D, immunochemical detection of DNPH derivatized proteins; Panels E, F and G show MDA, HNE and DNP total reactive quantities respectively. Panel G shows means of data obtained from duplicate western analyses.

Epitope specificity of the antibodies

An important criterion used for comparisons between the three antibodies was the Signal-to-Noise ratio (SNR). As shown in Fig. 1A-D, the SNR was relatively high, which (i) permitted the identification of distinct immunopositive bands with all of the three antibodies, and (ii) established the age-related variations in the immunodensities of different protein bands. However, it needs to pointed out that immunoblot analysis is essentially a semi-quantitative analytical technique, which is potentially vulnerable to several complicating factors, including the batch-to-batch variation in titer and epitope specificity. In particular, the anti-DNP antibodies seem to be quite problematic for quantitative comparisons, and also to be less specific compared to the antibodies against HNE and MDA adducts. The blots shown here are from experiments where the conditions were rigorously controlled. The differences in immunoreactivity of protein bands with anti-DNP antibodies, between successive ages, were found to be relatively subtle; however, distinct differences were discernable between the 15- and 60-day-old flies.

Age-related changes in levels of proteins with MDA-adducts

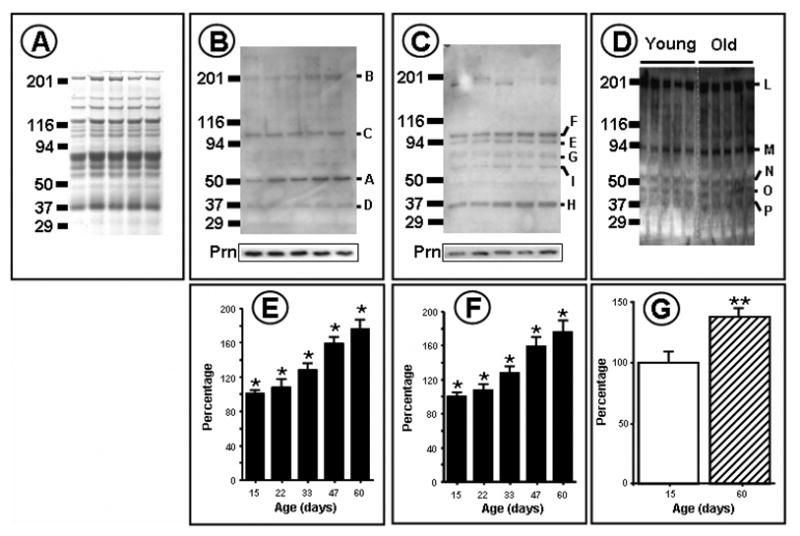

Mitochondrial proteins from flight muscles of 15-, 22-, 30-, 45- and 60-day-old flies were resolved by SDS-PAGE and processed for western analysis using anti-MDA antibodies (Figs. 1 and 2). Comparison of the combined density of the immunopositive proteins indicated that there was a progressive age-associated increase of ~110% in the total amount immunoreactivity between 15- and 60- days of age. Four distinct protein bands, labeled A–D (Fig. 2), were found to exhibit positive immunostaining at all of the five ages, but only two, A (~60 kDa) and B (~200 kDa), showed an age-related increase in immunodensity. The other two, C (~100 kDa) and D (~37 kDa), did not. The age-associated increase in the density of bands A and B was nearly linear, but different in magnitude, being ~85% in A and ~150% in B.

Figure 2. Immunochemical quantitation of individual HNE, MDA and DNP-protein bands from mitochondria from 15-, 22-, 30-, 45- and 60-day-old flies.

Panel C is based on duplicate western blots; D is from a typical immunoblot, where n= 5; other data are average of triplicate western analyses.

Age-related changes in amounts of proteins with HNE-adducts

Comparison of western blots of the mitochondrial proteins, using anti-HNE antibodies, was made between 15-, 22-, 33-, 47- and 60-day-old flies. During 15 and 60 days of age, the combined densities of the various immunoreactive proteins showed a progressive increase of ~80%. Seven distinct immunoreactive bands, ranging from 7 to 100 kDa in MW, were consistently observed at all the five ages. Two bands, J (~7 kDa) and K (~19 kDa), were designated as “minor”, because compared to the others they had relatively low levels of protein (Fig. 1A), however, the largest increase, per unit of protein in the band, occurred in the ~19 kDa “minor” band, J (Fig. 2C). All of the protein bands that were reactive with HNE-antibody, except one (K), showed an age-related increase in immunodensity, ranging from 65% to 200%.

Comparison of mitochondrial protein carbonyls between 15- and 60-day-old flies using anti-DNP antibodies

Anti-DNP antibodies are widely assumed to react with protein carbonyls originating from various sources, including MCO, HNE or MDA. To determine whether the protein bands showing positive immunoreactivity with anti-MDA and anti-HNE antibodies also react with anti-DNP antibodies, a comparison was made between 15 and 60 day-old-flies. All of the five protein bands, detected by anti-DNP antibodies, labeled L, M, N, O, and P, showed age-related increases in immunodensity, ranging from ~41% in band L (~200 kDa), ~71% in band M (~90 kDa), ~77% in band N (~50 kDa), ~107% in band O (~40 kDa) and ~83% in band P (~37 kDa). Comparatively, more protein bands reacted with HNE-antibodies and also showed an age-related increase in immunodensity than with anti-DNP or anti-MDA antibodies. The rank order of the percent increase in total immunoreactivity was anti-MDA > anti-HNE > anti-DNP.

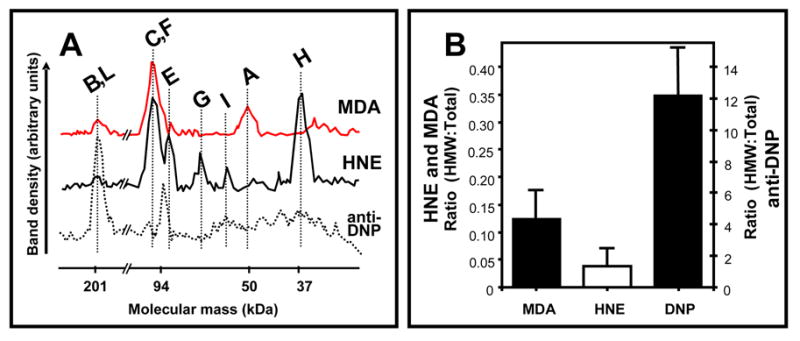

Comparison of levels of high molecular weight proteins with DNP HNE, and MDA adducts

One consequence of ROS attacks on proteins is inter-molecular cross-linking. As shown in Fig. 3B, the ratios of high-molecular-weight (HMW) to total immunoreactivity of the various proteins increased with age, with the rank order anti-DPN> anti-MDA>anti-HNE antibody.

Figure 3. Typical profile plots of immunoreactivity from Western analyses of MDA, HNE and anti-DNP post-translational modifications in Drosophila melanogaster mitochondrial proteins (A). Comparison of the ratio of high molecular weight (HMW) to Total immunostaining for HNE, MDA and anti-DNP protein modifications in Drosophila mitochondria (B).

Proteins were resolved and analyzed as described in “Materials and Methods”. ImageJ was used to determine the coordinates for individual profiles. Data are from typical samples of 33 day old D. melanogaster mitochondria, with the exception of the C=O bar in panel B, which compares 15 and 60 day-old-flies. Vertical bars represent standard error of the mean.

Densities of individual immunopositive bands are not dependent on their protein levels

An important issue in the localization of proteins that are targets of oxidative modifications is whether the intensity of the immunostaining is dependent upon the relative abundance of the specific proteins or on the frequency of the adducts. The former will favor the concept of random damage, while the latter would imply selectivity of the damage. A comparison of staining intensities of various bands, obtained by Coomassie blue staining, with those of western blots indicated that there was no obvious correspondence between them (compare the 116 kD band in Figs.1 and 3). This is consistent with the concept that protein oxidative damage during aging is not dependent upon the relative amount of a specific protein.

DISCUSSION

A novel feature of this study is that it compared the age-related pattern of carbonylation of mitochondrial proteins using three different antibodies, namely anti-DNP, anti-MDA and anti-HNE, which either localize epitopes solely comprised of carbonyl groups on the side chains of particular amino acid residues (anti-DNP), or recognize a larger epitope that contains carbonyl groups (anti-MDA and anti-HNE). Based on the historical view gained from the literature, our initial expectation was that the anti-DNP antibody would broadly react with the various carbonyl-containing protein bands. The results indicated that while the total amount of protein, reacting positively with of the three antibodies increased with age, the specific protein bands were not identical. A relatively greater variety of mitochondrial proteins showed reactivity with HNE, than with anti-DNP antibody. The patterns of HNE- and MDA-positive bands were also different from each other, suggesting that such adducts are formed with specific proteins. Thus on the basis of this study it may be suggested that multiple immunoprobes should be used for the localization of carbonylated proteins.

Carbonylation of proteins has been shown to arise by at least three different mechanisms: (i) by metal-catalyzed oxidation (MCO), (ii) by reaction with lipid peroxidation end-products containing aldehyde functional groups, such as HNE and MDA, and (iii) by interaction between glycine residues and sugars (glycation) or their oxidation products (glycoxidation). It has been suggested that MCO may the dominant mechanism for the carbonylation of soluble proteins in vivo [3, 15]. Early studies on the quantification of carbonylated proteins were based on derivatization of carbonyl groups with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) to hydrazone, followed by spectrophotometric detection of the resultant DNP-protein [26]. It was estimated that up to 30% of the protein from cells of old organisms versus 10% in the young may be carbonylated. Another concept also prevalent in the early literature was that oxidative damage to macromolecules, including proteins, was ubiquitous and random, as the reactions with free radicals are usually non-enzymatic in nature. However, later studies indicated that spectrophotometric estimates of the relative abundance of carbonylated proteins may be an overestimate, resulting from the presence of unreacted DNPH and nonprotein carbonyls [17–19]. More relevantly, studies involving immunological detection of DNP-proteins, where the proteins in the homogenate are electrophoretically separated, indicated that carbonylation was a selective phenomenon, whereby relatively few proteins showed positive immunoreaction with DNP-antibodies. Mitochondrial aconitase and adenine nucleotide translocase in the housefly were among the first proteins identified to exhibit an age-associated increase in carbonylation during aging [18, 19]. Later studies have considerably augmented this list, e.g. see [27]. Results of this study accord with the concept that protein carbonylation during aging is a selective rather than a ubiquitous or random phenomenon. For instance, a comparison of the Coomassie blue stained gels (Fig. 1A) with those stained immunologically (Figs.1B–D) demonstrates that only some of the bands observed in the former exhibit immunoreactivity in the latter.

A pertinent issue is: what is the physiological significance of protein carbonylation? Carbonyl groups are chemically reactive and act thermodynamically and kinetically as targets for nucleophilic attacks and the formation of Schiff bases with amines, which leads to protein cross-linking [28]. It is apparent from Fig. 3 that cross-linking of proteins indeed occurs in mitochondria during aging. MDA seems to be involved in the formation of a higher proportion of high molecular weight (>200 kDa) proteinaceous material than HNE, suggesting that the dialdehydic nature of MDA may be relatively more efficient in forming protein cross-links. On the other hand, anti-DNP immunoreactivity was also apparent in proteins with molecular weights of >200 kDa (Fig. 3). Cross-linking can block access to protease cleavage sites, thereby decreasing the rate of turnover and leading eventually to protein insolubility [29]. Another factor that may also contribute to the accumulation of cross-linked proteins is that activity of multicatalytic proteases tends to decline during aging [30]. Whatever the underlying factors may be, accumulation of cross-linked proteins has been widely hypothesized to be potentially cytotoxic.

Although it was initially widely held that carbonylation leads to a loss in protein catalytic activity, our recent studies on mitochondria from mouse heart and skeletal muscles have indicated that the presence of an oxidative modification in a protein is not an a priori evidence of loss of protein function. Similarly the absence of an age-associated increase in immunoreactivity does not suggest that there may be no further loss of protein function [31]. For instance, in mouse heart and kidney mitochondria, aconitase, very long chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase (VLCAD), the β-polypeptide of the mitochondrial F1 complex of ATP synthase, and the E2 component of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex were identified to exhibit MDA modification. Although there was no age-related increase in the amount of the MDA-modified proteins, aconitase and ATP synthase showed an age-related decrease in activity, while VLCAD and α-ketoglutarage dehydrogenase did not. Such data suggest that no assumptions about the loss of function of an oxidatively modified protein can be made solely based on the demonstration of carbonylation, without actual measurement of the specific activity. Data presented in this study form our initial characterization of targeted proteins for oxidative damage in Drosophila mitochondria, with subsequent aims being protein identification and determination of possible functional alterations.

In conclusion, results of this study indicate that mitochondrial proteins in Drosophila undergo a notable degree of carbonylation, particularly by forming adducts with lipid peroxidation products, 4HNE and MDA. These changes were selective and of sufficient magnitude to be potential indicators of oxidative stress.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the grant RO1 AG7657 from National Institute on Aging-National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Strehler BL. Time, Cells, and Aging. Academic Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comfort A. The Biology of Senescence. Elsevier; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stadtman ER. Protein oxidation and aging. Science. 1992;257:1220–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1355616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sohal RS, Weindruch R. Oxidative stress, caloric restriction, and aging. Science. 1996;273:59–63. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finkel T. Oxidant signals and oxidative stress. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:247–254. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Droge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boveris A, Cadenas E. In: Production of superoxide in mitochondria, in Superoxide Dismutase, II. Oberley LW, editor. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1982. pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chance B, Sies H, Boveris A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:527–605. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sastre J, Pallardo FV, Garcia de la Asuncion J, Vina J. Mitochondria, oxidative stress and aging. Free Radical Biol Med. 2000;32:189–198. doi: 10.1080/10715760000300201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferguson M, Mockett RJ, Shen Y, Orr WC, Sohal RS. Age-associated decline in mitochondrial respiration and electron transport in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem J. 2005;390:501–511. doi: 10.1042/BJ20042130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sohal RS, Dubey A. Mitochondrial oxidative damage, hydrogen peroxide release and aging. Free Radical Biol Med. 1994;16:621–626. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hillered L, Ernster L. Respiratory activity of isolated rat brain mitochondria following in vitro exposure to oxygen radicals. J Cerebr Blood F Met. 1983;3:207–214. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1983.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dean RT, Fu S, Stocker R, Davies MJ. Biochemistry and pathology of radical-mediated protein oxidation. Biochem J. 1997;324:1–18. doi: 10.1042/bj3240001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esterbauer H, Schaur RJ, Zollner H. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenol, malondialdehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radical Biol Med. 1991;11:81–128. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stadtman ER. Metal ion-catalyzed oxidation of proteins: biochemical mechanism and biological consequences. Free Radical Biol Med. 1990;9:315–325. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee AT, Cerami A. Role of glycation in aging. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1992;663:63–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb38649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sohal RS. Role of oxidative stress and protein oxidation in the aging process. Free Radical Biol Med. 2002;33:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00856-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan LJ, Sohal RS. Mitochondrial adenine nucleotide translocase is oxidatively modified during aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12896–12901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.12896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan LJ, Levine RL, Sohal RS. Oxidative damage during aging targets mitochondrial aconitase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11168–11172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies SMK, Poljak A, Duncan MW, Smythe GA, Murphy MP. Measurements of protein carbonyls, ortho- and meta-tyrosine and oxidative phosporylation complex activity in mitochondria from young and old rats. Free Radical Biol Med. 2001;31:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00576-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halliwell B, Whiteman M. Measuring reactive species and oxidative damage in vivo and in cell culture: how should you do it and what do the results mean? Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:231–255. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mockett RJ, Orr WC, Sohal RS. Overexpression of Cu,ZnSOD and MnSOD in transgenic Drosophila. Methods Enzymol. 2002;349:213–220. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)49336-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine R, Wehr N, Williams JA, Stadtman ER, Shacter E. Determination of carbonyl groups in oxidized proteins. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;99:15–24. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-054-3:15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rebrin I, Bayne ACV, Mockett RJ, Orr WC, Sohal RS. Free aminothiols, glutathione redox state and protein mixed disulphides in aging Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem J. 2004;382:131–136. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine RL, Garland D, Oliver CN, Amici A, Climent I, Lenz AG, Ahn BW, Shaltiel S, Stadtman E. Determination of carbonyl content in oxidatively modified proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:464–478. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86141-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi J, Forster MJ, McDonald SR, Weintraub ST, Carroll CA, Gracy RW. Proteomic identification of specific oxidized proteins in ApoE-knockout mice: relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radical Biol Med. 2004;36:1155–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friguet B, Stadtman ER, Szweda LI. Modification of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Formation of cross-linked protein that inhibits the multicatalytic protease. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21639–21643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Portero-Otin M, Pamplona R, Ruiz MC, Cabiscol E, Prat J, Bellmunt MJ. Diabetes induces an impairment in the proteolytic activity against oxidized proteins and a heterogeneous effect in nonenzymatic protein modifications in the cytosol of rat liver and kidney. Diabetes. 1999;48:2215–2220. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.11.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shringarpure R, Davies KJ. Protein turnover by the proteasome in aging and disease. Free Radical Biol Med. 2002;32:1084–1089. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00824-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yarian CS, Rebrin I, Sohal RS. Aconitase and ATP synthase are targets of malondialdehyde modification and undergo an age-related decrease in activity in mouse heart mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;330:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]