Abstract

tfoX (sxy) is a regulatory gene needed to turn on competence genes. Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans has a tfoX gene that is important for transformation. We cloned this gene on an IncQ plasmid downstream of the inducible tac promoter. When this plasmid was resident in cells of A. actinomycetemcomitans and tfoX was induced, the cells became competent for transformation. Several strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans, including different serotypes, as well as rough (adherent) and isogenic smooth (nonadherent) forms were tested. Only our two serotype f strains failed to be transformed. With the other strains, we could easily get transformants with extrachromosomal plasmid DNA when closed circular, replicative plasmid carrying an uptake signal sequence (USS) was used. When a replicative plasmid carrying a USS and cloned DNA from the chromosome of A. actinomycetemcomitans was linearized by digestion with a restriction endonuclease or when genomic DNA was used directly, the outcome was allelic exchange. To facilitate allelic exchange, we constructed a suicide plasmid (pMB78) that does not replicate in A. actinomycetemcomitans and carries a region with two inverted copies of a USS. This vector gave allelic exchange in the presence of cloned and induced tfoX easily and without digestion. Using transposon insertions in cloned katA DNA, we found that as little as 78 bp of homology at one of the ends was sufficient for that end to participate in allelic exchange. The cloning and induction of tfoX makes it possible to transform nearly any strain of A. actinomycetemcomitans, and allelic exchange has proven to be important for site-directed mutagenesis.

Keywords: periodontitis, pathogen, USS, allelic exchange, site-directed mutagenesis, competence

1. INTRODUCTION

Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobe of the Pasteurellaceae family that is found in the oral cavity (Henderson et al., 2003; Fine et al., 2006; Norskov-Lauritsen and Kilian, 2006). It is believed to cause localized aggressive periodontitis (LAP), a severe form of periodontal disease of adolescents, and several types of extraoral infections, including infective endocarditis, abscesses, meningitis, pneumonia, septicemia, urinary tract infections, and vertebral osteomyelitis (Zambon, 1985; Haffajee and Socransky, 1994; Slots, 1999; Henderson et al., 2003; Paturel et al., 2004; Fine et al., 2006). Fresh clinical isolates show a small, wrinkled (rough) colony form (Fine et al., 1999; Henderson et al., 2003; Kachlany et al., 2001a). The bacteria are known to produce several virulence factors, including a leukotoxin and a cytolethal distending toxin, and they adhere to solid surfaces and cells (Taichman and Wilton, 1981; Kolodrubetz et al., 1989; Lally et al., 1989; Eastcott et al., 1990; Mangan et al., 1991; Fives-Taylor et al., 1999; van Winkelhoff and Slots, 1999; Kachlany et al., 2001a; Narayanan et al., 2002; Henderson et al., 2003; Rose et al., 2003; Paturel et al., 2004; Rhodes et al., 2005; Diaz et al., 2006; Fine et al., 2005, 2006; Smith and Bayles, 2006). Clinical isolates autoaggregate and secrete long, bundled pili (Flp fibrils) (Holt et al., 1980; Scannapieco et al., 1987; Rosan et al., 1988; Inoue et al., 1998; Kachlany et al., 2001b; Henderson et al., 2003; Fine et al., 2006). In vitro A. actinomycetemcomitans can produce rare, stable, nonadherent, and nonaggregative genetic variants that form smooth, large colonies and fail to produce Flp fibrils (Wyss, 1989; Inouye et al., 1990; Fine et al., 1999, 2006; Kachlany et al., 2000, 2001a; Henderson et al., 2003).

Powerful genetic tools have contributed to the study of A. actinomycetemcomitans. The three natural methods for gene transfer (transformation, conjugation, and transduction) have all been observed in A. actinomycetemcomitans (Tϕnjum et al., 1990; Goncharoff et al., 1993; Willi et al., 1997; Galli et al., 2001). We previously developed an efficient method for conjugation-based transposon-insertion mutagenesis (Thomson et al., 1999) that allowed us to isolate three independent mutations in the catalase gene (katA) of A. actinomycetemcomitans (Thomson et al., 1999) and in genes involved in non-specific adherence (Kachlany et al., 2000, 2001b; Planet et al., 2003). For the latter, we identified the tad (tight adherence) locus, which encodes a novel secretion system responsible for the synthesis, assembly, and secretion of bundled type IVb pili, termed Flp fibrils (Kachlany et al., 2001a).

In this report we are concerned with transformation in A. actinomycetemcomitans and its utility as a genetic tool. Haemophilus influenzae is a Gram-negative bacterium that, like A. actinomycetemcomitans, is in the Pasteurellaceae family, and transformation has been well-studied in this organism (Smith et al., 1981; Lorenz and Wackernagel, 1994; Dubnau, 1999; Chen and Dubnau, 2004; Chen et al., 2005; Cameron and Redfield, 2006). Transformation probably involves binding of DNA to the cell surface and the formation of linear DNA in the periplasm that is then transported into the cytoplasm and recombined with the host genome. In H. influenzae there is evidence that double-stranded DNA is first taken up into structures known as “transformasomes” and that a single strand of DNA is transported across the inner membrane into the cytoplasm in a 3' to 5' direction, while the other strand is degraded (Concino and Goodgal, 1982; Barany et al., 1983; Kahn, et al., 1983; Dubnau, 1999).

Several genes are known to affect transformation in H. influenzae (Caster et al., 1970; Caster and Smith, 1972; Notani et al., 1972; Concino and Goodgal, 1982; Kooistra et al., 1983; Barouki and Smith, 1985, 1986; Tomb et al., 1989, 1991; Larson and Goodgal, 1991; Chandler, 1992; Dorocicz et al., 1993; Clifton et al., 1994; Gwinn et al., 1996, 1997, 1998; Chandler and Smith, 1996; Karudapuram and Barcak, 1997; Dougherty and Smith, 1999; Dubnau, 1999; Ma and Redfield, 2000; Chen and Dubnau, 2004; VanWagoner et al., 2004; Redfield et al., 2005, 2006; Cameron and Redfield, 2006; Smeets et al., 2006). The cAMP-CRP (cyclic-AMP receptor protein) complex helps to promote their expression and induce competence (the ability to take up and incorporate DNA) (Chandler, 1992; Redfield et al., 2005; Cameron and Redfield, 2006). Induction of competence in H. influenzae also requires the product of the tfoX (sxy) gene (Redfield, 1991; Williams et al., 1994; Zulty and Barcak, 1995; Redfield et al., 2005). TfoX helps CRP bind a non-canonical CRP site (CRP-S) to turn on the genes of the competence regulon (Redfield et al., 2005; Cameron and Redfield, 2006). The TfoX protein of H. influenzae itself does not seem to bind DNA, but to interact with CRP (Macfadyen, 2000; Redfield et al., 2005). Plasmids containing the tfoX gene make H. influenzae cells constitutively competent (Williams et al., 1994; Zulty and Barcak, 1995).

Many species of bacteria are known to develop competence in nature (Lorenz and Wackernagel, 1994; Dubnau, 1999), including A. actinomycetemcomitans (Tϕnjum et al., 1990), whose natural transformation is not understood. Currently natural transformation in A. actinomycetemcomitans appears to be strain-specific and is too low to be useful in many genetic studies (Wang et al., 2002; unpublished results). In some naturally transformable bacteria, competence is induced transiently during growth, whereas in others, it seems to be constitutive. Gram-positive bacteria, like the well-studied bacteria Bacillus subtilis and Streptococcus pneumoniae, and some Gram-negative bacteria, like Acinetobacter species (Dubnau, 1999; Chen and Dubnau, 2004) and Legionella pneumophila (X Charpentier and HA Shuman, personal communication), are able to take up DNA non-specifically. In contrast, some Gram-negative bacteria, such as H. influenzae, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and N. gonorrhoeae, take up their own DNA preferentially (Sisco and Smith, 1979; Goodman and Scocca, 1988; Smith et al., 1999; Bakkali et al., 2004; Hamilton and Dillard, 2006; Redfield et al., 2006). This specificity arises from the presence of Uptake Signal Sequences (USSs), also called DNA Uptake Sequences (DUSs), that occur frequently in their genomes (Smith et al., 1999; Dubnau, 1999; Chen and Dubnau, 2004; Redfield et al., 2006). In H. influenzae, the core USS is a 9-bp sequence, whereas in A. pleuropneumoniae, also in the Pasteurellaceae, the 9-bp sequence is different (Bakkali et al., 2004; Redfield et al., 2006). In Neisseria spp, the core USS is a 10-bp sequence that is distinct (Kroll et al., 1998). We were the first to report that the A. actinomycetemcomitans genome has numerous copies of a sequence identical to the 9-bp core USS of H. influenzae, and we predicted that the sequence is part of a USS, important to transformation in A. actinomycetemcomitans (Thomson et al., 1999). Experimental evidence indicates that the function of the sequence is indeed in transformation, as predicted (Wang et al., 2002, 2006; this work). Other studies have been concerned with the presence of USSs in the genomes of the Pasteurellaceae and the functional structure, origin, lineage, and evolutionary significance of the USSs (Bakkali et al., 2004; Redfield et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006).

H. influenzae-like transformation genes occur in the genome of A. actinomycetemcomitans (Wang et al., 2006; Cameron and Redfield, 2006; MK Bhattacharjee and DH Figurski, unpublished results), which is consistent with the ability of this organism to undergo natural transformation. In A. actinomycetemcomitans, genes also involved in the formation of a type IV pilus-like system, distinct from those that are responsible for Flp fibrils, are thought to be required for transformation (Wang et al., 2003). Although transformation of A. actinomycetemcomitans has been used for genetic studies (Tϕnjum et al., 1990; Sreenivasan et al., 1991; Sato et al., 1992; Kolodrubetz and Kraig, 1994; Wang et al., 2002; Fujise et al., 2004), transformation is not frequent enough or it requires specific strains. Importantly, the methods do not work on most of the strains that we have tested (data not shown).

We report here a general and efficient method for the transformation and site-directed mutagenesis of A. actinomycetemcomitans based on its tfoX gene. We show that nearly all strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans, including those with different serotypes, can be transformed. Transformation occurs with circular or linear DNA containing a USS when the cloned tfoX gene of A. actinomycetemcomitans is in trans on a plasmid and induced. Without the cloned tfoX, no transformants are recovered. Transformation with genomic DNA from A. actinomycetemcomitans results in allelic exchange with chromosomal DNA. Because there are more copies per μg of DNA, it is easier to get allelic exchange with cloned A. actinomycetemcomitans DNA either on a replicative plasmid that has been linearized or on a suicide plasmid. For best results, the plasmid should also contain a region with a USS. We also show that circular replicative plasmids containing a USS readily give transformants in which the plasmid replicates extrachromosomally.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Bacterial strains and culture conditions

For our experiments we used nalidixic acid-resistant (Nalr) versions of the strains, which are listed in footnote 1 of Table 1. A. actinomycetemcomitans was grown in AAGM (A. actinomycetemcomitans Growth Medium) with added bicarbonate in screw cap tubes (broth) or in a 10% CO2 atmosphere (agar), as described (Fine et al., 1999). Nalr mutants of A. actinomycetemcomitans strains were obtained by selection on AAGM plates containing 20 μg/ml nalidixic acid (Nal). Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Ausubel et al., 1989) with aeration or on LB agar. For A. actinomycetemcomitans, kanamycin (Km) was used at a final concentration of 40 μg/ml; streptomycin, at 20 μg/ml; and chloramphenicol (Cm), at 2 μg/ml; for E. coli, Km was used at 50 μg/ml; and Cm, at 50 μg/ml. Where indicated, isopropyl-β–D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added at the specified concentration. All strains used are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids (Sections 2.1, 2.3).

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| A. actinomycetemcomitans1 | ||

| Aa307 | Rough clinical isolate, serotype c | Haubek et al., 1995 |

| Aa1394 | Y4N katA2::IS903ϕkan, serotype b; Kmr, Nalr | Thomson et al., 1999 |

| Aa1395 | Y4N katA3::IS903ϕkan, serotype b; Kmr, Nalr | Thomson et al., 1999 |

| CU1000 | Rough clinical isolate, serotype f | Fine et al., 1999 |

| CU1060 | Spontaneous smooth variant of CU1000, serotype f | Fine et al., 1999 |

| DF2200 | Rough clinical isolate, serotype a | Kaplan et al., 2002 |

| IDH781 | Rough clinical isolate, serotype d | Haubek et al., 1995 |

| IDH1705 | Rough clinical isolate, serotype e | Haubek et al., 1995 |

| NJ9100 | Rough clinical isolate, serotype f | Kaplan et al., 2002 |

| Y4 | Smooth strain, serotype b | ATCC2 |

| E. coli | ||

| Top10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) ΔlacX74 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG (ϕ80lacZΔM15) |

Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1-TOPO | Cloning vector with 3′-T overhangs for ligation of Taq-amplified PCR products; Kmr, Apr | Invitrogen |

| pJAK12 | Broad-host-range IncQ expression vector, derivative of pMMB67HE with Ωfragment insertion in bla; lacIq, tacp, Mob+3; Smr |

J.A. Kornacki |

| pJAK13 | Same as pJAK12 with polylinker in opposite orientation | J.A. Kornacki |

| pJAK17 | Broad-host-range IncQ expression vector, derivative of pMMB67HE with Ωcat insertion in bla; lacIq, tacp, Mob+; Cmr |

J.A. Kornacki |

| pMB7 |

tfoX from A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4 cloned into pJAK17; Cmr |

This work |

| pMB8 |

tfoX from A. actinomycetemcomitans CU1000 cloned into pJAK17; Cmr |

This work |

| pMB22 | Y4 katA2::IS903ϕkan cloned into pJAK13 (Aa1394; Fig. 2A); Kmr; Smr |

This work |

| pMB40 |

katA region with two inverted copies of the USS in pJAK12 (Fig. 2B); Smr |

This work |

| pMB78 |

katA region with two inverted copies of the USS in pUC19 (Fig. 2B); Apr |

This work |

| pMB79 | Y4 katA3::IS903ϕkan cloned into pMB78; Kmr; Apr | This work |

| pMB88 | Promoterless katA from Y4 cloned into pMB78; Apr | This work |

| pMB89 - 93 | EZ::TN<KAN-2> at various positions in katA of pMB88 (Fig. 2C); Kmr; Apr |

This work |

| pUC19 | Cloning vector; ColE1 origin of replication; Apr | New England Biolabs |

A spontaneous Nalr mutant of each strain was isolated and used for all transformation studies. These strains are indicated with ‘N’ at the end and have the formal names shown in parenthesis: Aa307N (MB1230), CU1000N (CU1000N), CU1060N (CU1060N), DF2200N (MB1228), IDH781N (MB1220), IDH1705N (MB1221), NJ9100N (MB1259) and Y4N (Y4N).

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

Mob+, The plasmid is not self-transmissible in conjugation, but can be mobilized.

2.2 DNA Procedures

Genomic DNA was prepared according to a published procedure (Ausubel et al., 1989). Plasmid DNA was isolated using plasmid Miniprep kits (Qiagen). Amplification of DNA by PCR was done with Taq DNA polymerase, according to the manufacturer's (Qiagen) recommendations. Oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by Sigma. Restriction endonucleases and phage T4 DNA ligase were used as directed by the manufacturer (New England Biolabs). Separation of DNA by electrophoresis in gels has been described (Ausubel et al., 1989). Nucleotide sequences were determined by the Columbia University DNA sequencing facility using a Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems Automated DNA Sequencer 373A.

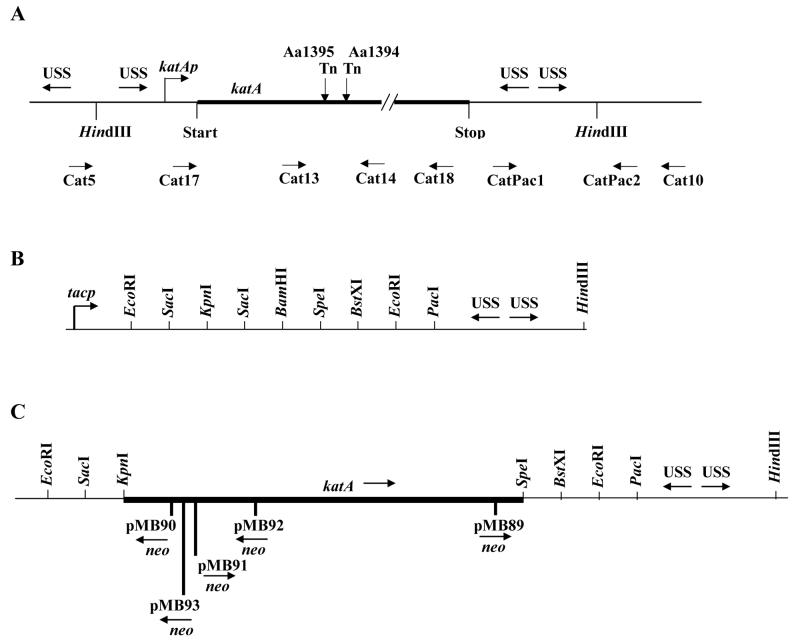

2.3 Plasmids

The broad-host-range, mobilizable IncQ plasmids, pJAK12, pJAK13, and pJAK17 (a gift from J. Kornacki) contain lacIq and tacp and are based on pMMB67HE and pMMB67EH (Fürste et al., 1986) where the selective markers interrupt the ampicillin-resistance gene. They and their derivatives were introduced into strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans by conjugative transfer with an oriT mutant of the IncP plasmid RK2, as described previously (Thomson et al., 1999). All plasmids are listed in Table 1. Constructed plasmids were made as follows. pMB7 and pMB8. The tfoX gene (Fig. 1) was amplified from A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4N and CU1000N by PCR, respectively, using primers TfoX up (5′- TAAAAAGCTTCCTGAAGGATTTAATTATGACAACGG-3′), which overlaps the first translational start, and TfoX dn (5′-GGTGGGATCCAAATGAAAAAACGCTCAATAGAGCGG-3′). The primers included the sequences for HindIII and BamHI restriction sites, respectively, at their 5′-ends. The PCR product was digested with HindIII and BamHI, then cloned into HindIII- and BamHI-cleaved pJAK17. When circular IncQ plasmids were used to transform cells, the resident tfoX+ plasmid was not selected and was lost by incompatibility. When digested plasmid or non-IncQ DNA (e.g., genomic DNA) was used, the resident tfoX+ plasmid and any incoming IncQ plasmid, was readily lost after one overnight because IncQ plasmids are unstable in A. actinomycetemcomitans in the absence of selection (unpublished results). pMB22. The mutated catalase gene (katA2::IS903ϕkan) of Aa1394 (Thomson et al., 1999) was amplified by PCR using primers Cat5 up (5′-ATCGCCGGTTTCGTGAAAGTC-3′) and Cat10 dn (5′-TGACCTGCTGCAAGTGTCTGA-3′). The PCR product was digested with HindIII, which cuts internally at two HindIII sites flanking the katA gene in the chromosome, and then cloned at the HindIII site of pJAK13. Clones were screened for the orientation in which the tac promoter of pJAK13 is present upstream of the katA promoter. The cloned DNA contains a mutated katA structural gene with its intact promoter, one copy of the USS upstream, and two inverted copies of the USS downstream (Fig. 2A). pMB40. The region containing two inverted copies of the USS downstream of katA was amplified by PCR using primers CatPac1 up (5′-CCTTAATTAATACGGAATTGGCAAACGCC-3′) and CatPac2 dn (5′- CCTTAATTAACACTATAATTTGGTGAATTTC-3′), which include sequences for restriction sites for PacI, and then cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO, following the manufacturer's (Invitrogen) recommendations. The PCR product contained one HindIII site close to the USS region. Clones were screened for the orientation of the insert, in which the USS region was flanked by HindIII sites, one from the PCR product and one from the vector. A HindIII–KpnI fragment was cloned into HindIII- and KpnI-cleaved pJAK12 to give pMB40. Its polylinker region contains the following sites in sequence: EcoRI, SacI, KpnI, SacI, BamHI, SpeI, BstXI, EcoRI, PacI, inverted USS repeats, and HindIII (Fig. 2B). pMB78. The HindIII-KpnI fragment of pMB40 that contains the inverted USS repeats from katA was cloned into HindIII- and KpnI-cleaved pUC19 to give pMB78, which contains the same order of restriction sites and USSs in the polylinker region as pMB40 (Fig. 2B). pMB79. A promoterless katA gene from Y4N katA3::IS903ϕkan (Aa1395) (Thomson et al., 1999) was amplified using primers Cat17 up (5′-CTTTTTGCTGGTACCTATAATTTCTGTC-3′) and Cat18 dn (5′-GGTTGTGACTAGTAATCTTCGTCG-3′) (Fig. 2A), which contain sequences for KpnI and SpeI sites, respectively. After digestion, the resulting KpnI-SpeI fragment was cloned into KpnI- and SpeI-digested pMB78. pMB88. A promoterless katA gene from Y4N was amplified using primers Cat17 up and Cat18 dn and cloned into pMB78, following the same procedure as described for the construction of pMB79. pMB89-pMB94. Isolated pMB88 DNA was subjected to in vitro transposon mutagenesis with EZ::TN<KAN-2> (Epicenter), using the manufacturer's recommendations. E. coli Top10 competent cells were transformed with the resulting library of pMB88 EZ::TN<KAN-2> mutants, all of which contained an expressed Km-resistance gene (neo) that occurs in the transposon. Km-resistant (Kmr) colonies were screened for those that contained the transposon inserted in the cloned katA gene. The positions and orientations of the insertions (Fig. 2C) were determined by PCR using two sets of primers, each of which contained one primer at one of the two ends of the neo gene (from Epicenter) and one in the vector.

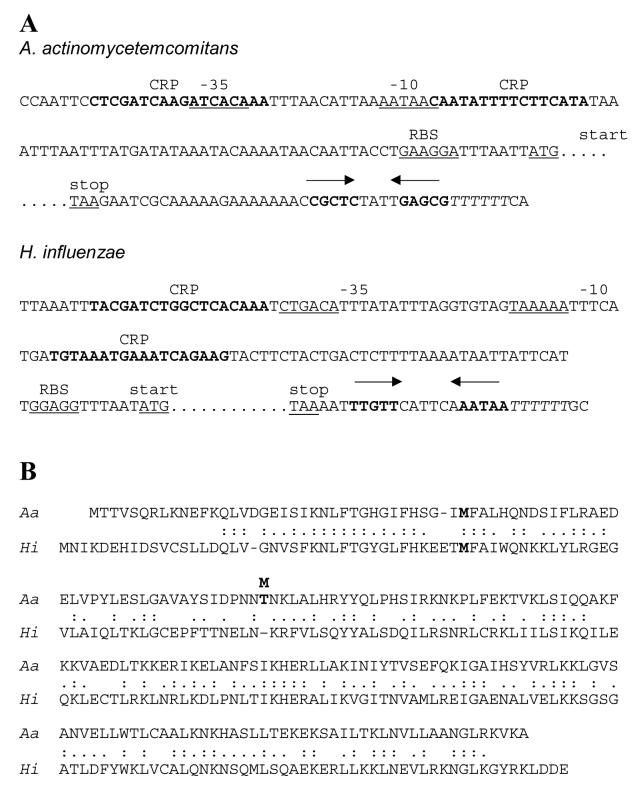

Fig 1.

Comparison of the tfoX regions of A. actinomycetemcomitans and H. influenzae (Section 2.3). A. Nucleotide sequences of the regions upstream and downstream of the tfoX structural gene, which is delimited by “start” and “stop,” from A. actinomycetemcomitans HK1651 (Roe et al., 2006) and H. influenzae Rd (Zulty and Barcak, 1995). Potential ribosome-binding sites (RBS) and CRP-binding sites (CRP) are indicated. σ70-like promoter sequences are marked by “−35” and “−10.” The inverted repeat sequences that can serve as potential intrinsic terminators are shown by convergent arrows. They are followed by six T's shown in italics. The potential CRP and terminator sequences are in bold. Potential RBS, −35, −10, start, and stop sequences are underlined. B. Alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences of the TfoX proteins. Aa is A. actinomycetemcomitans; Hi, H. influenzae. Identical (:) and similar (.) amino acids are indicated. At position 73 the bold 'M' (CU1000) above the bold 'T' (Y4 and HK1651) indicates the amino acid difference in TfoX from CU1000.

Fig 2.

Molecular genetic maps (Section 2.3). A. Map of the katA region of A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4N (not to scale) (Thomson et al., 1999) showing uptake signal sequences (USS), positions of transposon IS903ϕkan (Tn) insertions in strains Aa1394 and Aa1395, and the names, positions, and orientations of the primers used for PCR (arrows). B. Relative positions of the tac promoter (tacp), restriction sites, and the USSs in pMB40. The order of restriction sites and the USSs is the same in pMB78. C. Positions and orientations of the EZ::TN<KAN-2> transposon in pMB89, pMB90, pMB91, pMB92 and pMB93. The arrow below each indicates the direction of neo, which arbitrarily orients the transposon.

2.4 Transformations

E. coli Top10 cells (Invitrogen) were transformed according to the manufacturer. Competent cells of A. actinomycetemcomitans smooth (nonadherent) strains were made as follows. A. actinomycetemcomitans strains containing the cloned tfoX gene of Y4N or CU1000N were streaked onto plates supplemented with Cm and incubated at 37°C for 3-4 days. Individual colonies were then inoculated into 5-10 ml of AAGM broth containing 2 μg/ml Cm and grown at 37°C overnight. We added Cm to the growth medium to select for the tfoX+ plasmid. The overnight culture was used to inoculate (1:100) 10 ml of fresh AAGM broth containing Cm. The culture was grown for 3-4 hr at 37°C or until an A600 reading of 0.1-0.2. TfoX expression was induced by adding 1 mM IPTG, and the culture was grown for another 1 hr at 37°C. Although the optima (Table 2) were found to be 0.2 mM IPTG and an A600 of 0.6, the conditions used routinely were adequate and more convenient. The A600 was measured and the cells were pelleted at 7K rpm for 5 min in a Sorvall SS34 rotor. The cells were resuspended in the appropriate volume of the same medium with IPTG to give a final A600 reading of 1.0.

TABLE 2.

| Induction | ||||||

| mM IPTG | 0 (1.8)3 | 0.02 (10.4) | 0.10 (8.0) | 1.0 (7.0) | ||

| Absorbance | ||||||

| A600 | 0.071 (0.72) | 0.205 (6.6) | 0.393 (7.1) | 0.628 (25.2) | 0.830 (10.7) | 1.017 (4.9) |

| Amount of transforming DNA | ||||||

| μg genomic DNA | 0 (0) | 5 (1.3) | 10 (1.2) | 20 (7.1) | 30 (6.1) | 50 (3.1) |

Transformation was done as described in Materials and Methods (Section 2.4), except for one variable in each experiment as indicated. An equal number of cells was used for each transformation. DNA was genomic DNA from Y4N katA3::IS903ϕkan.

Y4N(pMB7) was transformed; Y4N without pMB7 gave no transformants.

Numbers in parentheses indicate transformants/μg DNA.

Competent cells of A. actinomycetemcomitans rough (adherent) strains were transformed as follows. Ten ml AAGM broth containing Cm was inoculated with a fresh colony from an AAGM plate (with Cm) and grown overnight at 37°C. The overnight culture of A. actinomycetemcomitans was supplemented with 1 mM IPTG and incubated at 37°C for 1 hr. (See the above note about the optima from Table 2.) The cells were scraped from the walls of the tube with a sterile wooden dowel (Fisher) and pelleted at 7K rpm for 5 min in a Sorvall SS34 rotor. One ml of the supernatant was saved for later use. Clumps of cells were resuspended in 20-50 μl of the saved broth and disrupted with a disposable mortar and pestle (ISC Bioexpress). The cells were then resuspended in the remainder of the saved supernatant. To obtain single cells, the suspension was centrifuged in an Eppendorf microfuge for 5 sec to remove debris and remaining clumps, and the supernatant was filtered through a 5 μm filter (Fisher). The filtrate contained mostly single cells, as seen under a microscope. This filtration step to obtain single cells is only required for calculating transformation efficiencies.

For transforming both adherent and nonadherent strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans, 20 μg genomic DNA or 0.1 μg of DNA from pUC19-based plasmids (pUC19, pMB78, pMB79, pMB89-93) or 0.5 μg of DNA from pJAK13-based plasmids (pJAK13, pMB22, pMB40) in a small volume of buffer (1-5 μl) was added to 100 μl of competent cells (nonadherent or adherent) and incubated at 37°C for 2-4 hr. Transformants were selected by spreading transformed cells on AAGM plates containing the appropriate antibiotic.

3. RESULTS

3.1 The tfoX (sxy) gene of A. actinomycetemcomitans

A search of the A. actinomycetemcomitans genome database (Cameron and Redfield, 2006; Roe et al., 2006; MK Bhattacharjee and DH Figurski, data not shown) revealed the presence of a tfoX-like gene (coordinates 385359-384727), whose product has 41% amino acid identity with that from H. influenzae (Fig. 1). The tfoX gene of A. actinomycetemcomitans shares many properties with the tfoX gene from H. influenzae (Zulty and Barcak, 1995). It has two potential ribosome-binding sites and can give a protein of 24.0 kDa, which is similar to what is observed in H. influenzae. The pIs of the predicted TfoX proteins are 9.5 for H. influenzae and 9.8 for A. actinomycetemcomitans. The tfoX gene of H. influenzae is regulated by CRP. Based on the E. coli consensus sequence for CRP-binding (Harrison and Aggarwal, 1990), we identified two potential CRP-binding sites in the upstream region of tfoX from A. actinomycetemcomitans. We do not know if either is functional, but there is evidence that cAMP can affect transformation in A. actinomycetemcomitans (Wang et al., 2002). Also upstream of the tfoX-coding sequence in A. actinomycetemcomitans is a σ70-like promoter sequence. Downstream, as in H. influenzae, is an inverted repeat sequence with the potential to form a stem-loop structure followed by several uridine residues, a characteristic feature of factor-independent transcription terminators (Platt, 1981).

3.2 tfoX-dependent transformation of A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4N

The tfoX gene from A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4N was cloned onto an IncQ tacp expression plasmid to test production of competence in Y4N after induction of the cloned gene with IPTG. Transformations were done with genomic DNA from the katA insertion mutant strain Y4N katA3::IS903ϕkan (Aa1395, Fig. 2A) (Thomson et al., 1999). Kmr transformants were selected and screened for their inability to show catalase activity (Thomson et al., 1999). When tfoX was in trans and induced, Y4N could be transformed easily (Tables 2 and 3). No transformants were seen in the absence of cloned tfoX. The low level of transformation in the absence of inducer, IPTG, (Table 2) is probably due to the leaky nature of the tac promoter. The number of transformants increased upon induction of the cloned tfoX gene with a low level of IPTG (0.02 mM), but showed a slight decrease at higher levels of IPTG (0.1 mM and above), the reason for which is not known. In terms of absorbance, maximum competence was reached at A600 of 0.6 and decreased significantly thereafter (Table 2). The transformation efficiency also increased with increasing amounts of transforming DNA and reached a maximum at 20 μg of total genomic DNA (Table 2). For routine transformations, we used about 20 μg of genomic DNA.

TABLE 3.

Transformation of various strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans with genomic DNA.

|

Transformants/μg DNA1 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Colony Phenotype2 |

Serotype | Resident Plasmid |

katA3::IS903ϕkan3 | tadE::IS903ϕkan4 |

| DF2200N | R | a | pMB7 | 111.8 | 1.8 |

| Y4N | S | b | vector5 | 0 | 0 |

| Y4N | S | b | pMB7 | 5.9 | 0 |

| Aa307N | R | c | pMB7 | 7.6 | ND6 |

| IDH781N | R | d | pMB7 | 120.9 | 0.8 |

| IDH781N (Single Cells) |

R | d | pMB7 | 2573.3 | ND |

| IDH1705N | R | e | pMB7 | 23.8 | 0 |

| IDH1705N | S7 | e | pMB7 | 0.16 | ND |

| CU1000N8 | R | f | pMB7 | 0 | 0 |

| CU1060N8 | S | f | pMB7 | 0 | 0 |

| NJ9100N | R | f | pMB7 | 0 | ND |

Transformation was done as described in Materials and Methods (Section 2.4). Transformants were selected on AAGM plates containing kanamycin.

S: smooth; R: rough.

Genomic DNA from Y4N katA3::IS903ϕkan.

Genomic DNA from CU1000N tadE::IS903ϕkan.

Vector (pJAK17) control for all other strains gave no transformants.

ND, not determined.

A spontaneous smooth variant of IDH1705N with the formal name MB1221.

The same results were obtained with pMB8 as the resident plasmid.

3.3 Transformation of recent clinical isolates

To transform adherent strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans, we tested the competence of Nalr derivatives of several recent clinical isolates (Table 1). Nearly all of the isolates, of varying serotypes, could be transformed when the cloned tfoX gene of A. actinomycetemcomitans strains Y4N or CU1000N was present in the cells (Table 3; data not shown). Although strains DF2200N (serotype a) and IDH781N (serotype d) transformed at about 20-times higher efficiency than Y4N, some gave lower efficiencies. There was no apparent correlation of transformation efficiency with serotype (except possibly for serotype f, see below). Rough (adherent) cells were transformed at higher efficiency than their isogenic smooth (nonadherant) variants (compare the rough and smooth strains of IDH1705N, Table 3). We have shown before that rough A. actinomycetemcomitans can form large clumps, each of which can contain millions of cells (Kachlany et al., 2000). Consistent with that observation, we found that the transformation efficiencies of the rough strains can be even higher with single cells. When single cells of rough A. actinomycetemcomitans IDH781N were prepared and used, a 20-fold increase in transformation efficiency was observed (Table 3). We postulated that either all cells in a clump may not be accessible to the transforming DNA or that each clump may contain several transformants, but only give rise to a single colony.

Serotype f strains (CU1000N and NJ9100N) did not transform (Table 3), not even when single cells were used (data not shown), while strains of all other serotypes gave transformants. One possible reason for the inability to yield transformants is restriction-modification. To test this possibility, we used genomic DNA from a random library of IS903ϕkan insertion mutants made in the serotype f strain CU1000N (Thomson et al., 1999). Because the mutants came directly from a serotype f strain, they should all be modified and not be subject to restriction by that strain. While we could obtain transformants in strains of other serotypes, we were never able to obtain transformants in our serotype f strains. This result shows that the lack of transformation in serotype f strains is not due to restriction-modification.

3.4 Transformation is helped by a USS

Most of the A. actinomycetemcomitans strains that could be easily transformed with genomic DNA for katA::IS903ϕkan could rarely be transformed for tadE::IS903ϕkan. katA has four flanking USSs (Fig. 2A). tadE is a gene well within the tad locus (Kachlany et al. 2000); no USSs were found in a search of the 14-kb tad locus sequence from strains HK1651 (Roe et al., 2006) or CU1000 (Planet et al., 2003).

Only the two highly competent strains, DF2200N and IDH781N, gave tadE::IS903ϕkan transformants, but at a 100-fold lower efficiency than katA::IS903ϕkan. The few tadE::IS903ϕkan transformants that we obtained may have arisen by using a USS present outside the tad locus. The closest USS is 3.0 kb downstream of the Km-resistance gene (kan) from the IS903ϕkan insertion in tadE.

3.5 Transformation with plasmid DNA

We tested if plasmid DNA can be used to transform A. actinomycetemcomitans and replicate. An IncQ broad host-range plasmid is known to replicate in A. actinomycetemcomitans (Goncharoff et al., 1993; Table 4). We found that extrachromosomal pMB22 plasmid DNA could be recovered after transformation (data not shown) and that the presence of a USS was important (e.g., compare pJAK13 with pMB40, Table 4), although occasionally one or two transformants were seen with pJAK13, which does not have a USS. pMB22 is a derivative of pJAK13 that has katA::IS903ϕkan and three USSs (Table 1; Fig. 2A). Circular pMB22 plasmid DNA transformed DF2200N(pMB7) at high efficiency (Table 4). The transformants were both Km- and streptomycin-resistant, as expected for the complete plasmid. pMB22 extrachromosomal DNA could be isolated from the transformants (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Allelic exchange after transformation with IncQ Plasmid DNA.

| Strain1 | Colony Phenotype2 |

Transforming DNA3 |

Relevant Features |

Transformants4 /μg DNA |

Catalase Phenotype5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF2200N | R | pJAK13 | Vector, circular | 0 | ND |

| DF2200N | R | pMB40 | 2 USS, circular | 1.7 × 104 | + |

| DF2200N | R | pMB22 |

katA3::IS903ϕkan 3 USS, circular |

5.1 × 102 | + |

| DF2200N | R | pMB22 + PstI |

katA3::IS903ϕkan 3 USS, linear |

1.7 × 102 | − |

| Y4N | S | pJAK13 | Vector, circular | 0 | ND |

| Y4N | S | pMB22 |

katA3::IS903ϕkan 3 USS, circular |

3.0 | + |

| Y4N | S | pMB22 + PstI |

katA3::IS903ϕkan 3 USS, linear |

6.0 | − |

Both strains contained the plasmid pMB7 and were transformed as described in Materials & Methods (Section 2.4).

S, smooth; R, rough

0.5 μg plasmid DNA was used for each transformation.

Transformants were selected on AAGM plates containing kanamycin for pMB22 or streptomycin for pJAK13 and pMB40.

+ indicates that all transformants tested showed catalase activity; − indicates that all transformants tested did not show catalase activity; ND, not done. All Y4N transformants were tested; 30 DF2200N transformants were tested for each different DNA. Allelic exchange was confirmed by PCR (see text).

3.6 Allelic exchange

pMB22 DNA digested with PstI gave a similar number of transformants as did the corresponding circular DNA. This result is similar to what was observed for circular and linear plasmid DNA in H. influenzae by Gromkova and Goodgal (1981), but different from transformation of chemically-competent E. coli, in which transformation with linear plasmid DNA is about 1000-fold less efficient than transformation with circular plasmid DNA (Shigekawa and Dower, 1988).

The different forms of plasmid gave different products. When the transformation was done with digested (linear) katA-mutant plasmid pMB22, all the resulting A. actinomycetemcomitans transformants tested were catalase-negative, while those obtained with undigested (circular) pMB22 DNA were all catalase-positive. This can happen if, after entering the cell, the linear DNA does not recircularize but undergoes allelic exchange with the chromosome. In contrast, circular pMB22 DNA probably replicates as an extrachromosomal plasmid, and the chromosomal katA remains intact. As evidence for this hypothesis, circular pMB22 plasmids could be isolated from the catalase-positive (circular plasmid DNA) transformants (data not shown). Allelic exchange with the chromosome in the catalase-negative (linearized plasmid DNA) transformants was confirmed by PCR, using primers Cat13 up and Cat14 dn that flank the IS903ϕkan insertion (Fig. 2A). Transformants arising from undigested (circular) plasmid DNA gave two bands that corresponded to the wild-type katA gene present in the chromosome and the mutated katA gene on the plasmid. Transformants arising from digested (linearized) plasmid DNA gave only one PCR product that corresponded to katA::IS903ϕkan. These results indicate allelic exchange with the chromosome from transformation with linear plasmid DNA.

Transformation with IncQ plasmids is useful for studies in which a replicating plasmid is needed. To get allelic exchange easily, we constructed a suicide vector, a pUC19 derivative (pMB78) that cannot replicate in A. actinomycetemcomitans (Galli et al., 1996) and has two inverted copies of the USS in the polylinker (Table 1; Fig. 2B).

A promotorless mutant katA from Y4N katA3::IS903ϕkan (Aa1395) was cloned into pMB78 to give pMB79 (Table 1). Both undigested (circular) and digested (linear) pMB79 gave Kmr transformants (Table 5). Because the cloned katA DNA lacks the katA promoter (Fig. 2A), expression of Kmr indicated that kan was expressed from the chromosomal katA promoter after homologous recombination with the chromosome. This arrangement was confirmed by PCR. All 30 transformants tested in each experiment were catalase-negative and 10/10 tested gave only one PCR product that corresponded to the mutant katA (data not shown). The absence of a PCR product that corresponded to the wild type katA gene indicated that double homologous recombination took place to replace the intact chromosomal katA gene.

TABLE 5.

Transformation with a suicide vector.1

| Transforming DNA2 | Relevant Features | Transformants/μg DNA |

|---|---|---|

| pUC19 | Vector circular plasmid DNA |

0 |

| pMB78 | 2 USS circular plasmid DNA |

0 |

| pMB79 |

katA3::IS903ϕkan, 2 USS, circular plasmid DNA |

2.9 × 104 |

| pMB79 + SpeI |

katA3::IS903ϕkan, 2 USS, linear plasmid DNA |

1.1 × 105 |

| pMB79 + KpnI |

katA3::IS903ϕkan, 2 USS, linear plasmid DNA |

2.3 × 105 |

| Y4N katA3::IS903ϕkan | katA3::IS903ϕkan genomic DNA | 5.0 × 102 |

DF2200N(pMB7) was transformed as described in Materials and Methods (Section 2.4). Transformants were selected on AAGM plates containing kanamycin.

0.1 μg DNA for plasmids; 20 μg DNA for genomic DNA.

When pMB79 was digested with KpnI, the cloned katA DNA remained adjacent to the USSs. When the plasmid was digested with SpeI, the cloned katA DNA and the USS region were at the two ends of the linear DNA. Both digested plasmid DNAs could transform and undergo allelic exchange indistinguishably (Table 5). On a molar basis for a particular gene, transformation and allelic exchange with genomic DNA was about as efficient as that with digested plasmid DNA carrying the cloned gene (Table 5).

3.7 Homology sufficient for allelic exchange

The plasmids pMB89, pMB90, pMB91, pMB92, and pMB93 were made by in vitro insertions of EZ::TN<KAN-2> (a derivative of Tn5) at different positions in katA in pMB88 (Table 1; Fig. 2C), which contains a promoterless katA gene. The plasmids were digested with KpnI or SpeI and used to transform A. actinomycetemcomitans DF2200N(pMB7). Transformants were selected by the Kmr from the transposon insertions, then screened for loss of catalase activity to indicate allelic exchange with the chromosome. We observed an orientation effect. When the neo gene of the EZ::TN<KAN-2> insertion mutants was in the same direction as katA, transformants were abundant (Table 6), but there were fewer transformants when the insertion was in the opposite orientation. The different insertions also allowed us to test how little homologous sequence at an end of the transposon allowed allelic exchange to occur. We found that 78 bp of homology at one end still allowed that end to participate in allelic exchange (see pMB89, Table 6). Whether 78 bp of homology is sufficient at both ends of the transforming DNA could not be ascertained from this experiment.

TABLE 6.

Homology sufficient at one end for allelic exchange.

| Plasmid | Homology (bp) beyond the two ends of the transposon1 |

Relative orientation2 |

Transformants3/μg DNA |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear DNA |

Circular DNA | ||||

| KpnI cut | SpeI cut | ||||

| pMB89 | 1318, 78 | + | 1.3 × 105 | 6.6 × 104 | 3.0 × 104 |

| pMB90 | 170, 1226 | − | 2.2 × 103 | 3.2 × 103 | 5.0 × 102 |

| pMB91 | 288, 1108 | + | 6.2 × 104 | 1.2 × 105 | 4.0 × 104 |

| pMB92 | 481, 915 | − | 5.7 × 103 | 1.5 × 103 | 5.0 × 102 |

| pMB93 | 275, 1121 | − | 9.0 × 102 | 7.0 × 102 | 1.0 × 103 |

Homology beyond the two ends of the transposon was determined by sequencing outwards from the ends of the transposon.

+ indicates katA and neo are oriented in the same direction; − indicates they are oriented in opposite directions. The orientations were determined by sequencing outwards from either end of the transposon.

DF2200N(pMB7) was transformed as described in Materials and Methods (Section 2.4). All transformants tested had replaced the wild type katA gene (chromosomal) with a mutant gene (plasmid-borne), as determined by PCR.

4. DISCUSSION

A. actinomycetemcomitans has a tfoX gene, which, when cloned and induced, can make almost any strain of A. actinomycetemcomitans competent for transformation. Only our two serotype f strains failed to give any transformants. High transformation efficiency also requires a nearby USS, and it works in the polylinker of the plasmid suicide vector that we constructed. A USS has been shown to be important for transformation in A. actinomycetemcomitans (Wang et al., 2002, 2006). The use of linearized replicative plasmid DNA, circular suicide plasmid DNA, or genomic DNA readily yields transformants that have undergone allelic exchange with the chromosome. (One of the ends of the incoming DNA can have as little as 78 bp of homology.) The use of plasmid DNA to get allelic exchange has been helpful for site-directed mutagenesis of chromosomal genes (see, e.g., Kaplan et al., 2004; Fine et al., 2005; Rhodes et al., 2005; Perez et al., 2006). Transformation with undigested replicative plasmid DNA can yield A. actinomycetemcomitans strains that carry an extrachromosomal plasmid. Like allelic exchange, transformation to give extrachromosomal plasmid is most efficient if the plasmid carries a USS.

The maximum transformation efficiency we obtained for A. actinomycetemcomitans was for single cells. We disrupted clumps of cells with a disposable mortar and pestle before adding the DNA for routine transformation experiments. While transformation was improved, this method is not efficient for making single cells quantitatively.

To express TfoX in different strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans, we cloned tfoX from A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4N and CU1000N into an IncQ vector and put them under the control of the inducible tac promoter. One amino acid difference occurs at position 73, which is Thr in Y4N tfoX and Met in CU1000N tfoX (Fig. 1B). Both genes worked equally well in our transformation procedure. Because we were able to transform nearly all strains we tested (Table 3), these strains very likely have all the necessary genes for natural transformation, as has been described for A. actinomycetemcomitans HK1651 (Cameron and Redfield, 2006). It remains to be seen whether the induction of the resident chromosomal tfoX gene in strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans can increase the natural transformation efficiency, but we believe it would. The ability to be transformed may be a general property of A. actinomycetemcomitans, except maybe in serotype f strains. The failure to transform serotype f strains CU1000N and NJ9100N is not due to restriction-modification (Section 3.3). We cannot ascertain at present whether serotype f strains are not competent or whether they transform in our method at a level below what we can detect (about 1 transformant in 109 cells). The presence or absence of complete sets of transformation genes in the genomes of these strains would be an important clue.

Development of competence in bacteria is usually tightly regulated (Dubnau, 1999; Chen and Dubnau, 2004; Sexton and Vogel, 2004), but it is not yet known what signals competence in A. actinomycetemcomitans. The environmental signal for the development of competence in H. influenzae is not known either, but an increase in adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP) level triggers the expression of the early competence gene tfoX (Wise et al., 1973; Dorocicz et al., 1993; Redfield et al., 2005). The TfoX protein then activates other competence genes (the competence regulon) through CRP at CRP-S sites (Redfield et al., 2005; Cameron and Redfield, 2006). Competence of A. actinomycetemcomitans D7S can be stimulated by cAMP (Wang et al., 2002), but added cAMP did not significantly increase competence in the various A. actinomycetemcomitans strains we used here with cloned tfoX (MK Bhattacharjee, unpublished results). One possible explanation for this observation is that the cells have enough cAMP in these growth conditions to accommodate the increase in TfoX that results from induction of the cloned gene. This possibility would bypass a requirement for the addition of exogenous cAMP to increase transformation efficiency. A similar result was reported for cloned tfoX on a plasmid in H. influenzae (Zulty and Barcak, 1995).

In our method for making competent A. actinomycetemcomitans, we observed that both circular and digested plasmids were able to transform (Tables 4 and 5), but they led to different outcomes. Incoming circular DNA is linearized by the transformation process; but, because there is a resident IncQ plasmid (with tfoX), we may be selecting recombinants in which the linear incoming plasmid has recombined with the homologous resident plasmid to form a cointegrate that is resolved to give two IncQ monomeric plasmids (Gryczan et al., 1980). Regardless, the ease of obtaining allelic exchange in A. actinomycetemcomitans has important applications in creating site-specific mutations. We and others are currently using this approach to make mutations in several regions of interest in the chromosome.

5. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Robert Chang for his help at the beginning of this work. We are particularly grateful to Brenda Perez and Scott Kachlany for discussions about the work and to Sarah Clock, Mladen Tomich, and Paul Planet for their comments on the manuscript. DH Figurski also deeply appreciates the help of Saul Silverstein and Aaron Mitchell. This work was supported by NIH grant R01 DE014713 to DH Figurski.

Abbreviations

- A600

absorbance of light at wavelength 600 nm

- AAGM

A. actinomycetemcomitans Growth Medium

- bp

base pairs

- C

Centigrade

- cAMP

adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- Cm

chloramphenicol

- CRP

cAMP receptor protein, also called the catabolite activator protein

- CRP-S

non-canonical CRP binding-site recognized by CRP in the presence of TfoX

- EZ::TN<KAN-2>

derivative of Tn5 used for mutagenesis in vitro

- hr

hour(s)

- Inc

plasmid incompatibility group

- IPTG

isopropyl-β–D-thiogalactopyranoside

- IS903ϕkan

artificial transposon based on Tn903

- K

x 1000

- Km

kanamycin

- kan

gene of Tn903 for kanamycin-resistance

- katA

catalase gene of A. actinomycetemcomitans

- kb

kilobase pair(s)

- lacIq

E. coli mutation that results in high level of LacI repressor

- LAP

localized aggressive periodontitis

- LB

Luria-Bertani medium

- min

minute(s)

- ml

milliliter(s)

- mM

millimolar

- Nal

nalidixic acid

- neo

gene of Tn5 for kanamycin-resistance

- ORF

open reading frame

- oriT

origin of transfer

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- r

resistant

- rpm

rotations per minute

- s

sensitive

- sec

second(s)

- tacP

tac promoter

- tfo

transformation

- tad

tight adherence

- μg

microgram(s)

- μl

microliter(s)

- μm

micrometer(s) or micron(s)

- USS

uptake signal sequence

- ::

insertion

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

6. REFERENCES

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons. Inc.; New York, N.Y.: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bakkali M, Chen TY, Lee HC, Redfield RJ. Evolutionary stability of DNA uptake signal sequences in the Pasteurellaceae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:4513–4518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306366101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barany F, Kahn ME, Smith HO. Directional transport and integration of donor DNA in Haemophilus influenzae transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1983;80:7274–7278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.23.7274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouki R, Smith HO. Reexamination of phenotypic defects in rec-1 and rec-2 mutants of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. J. Bacteriol. 1985;163:629–634. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.2.629-634.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouki R, Smith HO. Initial steps in Haemophilus influenzae transformation. Donor DNA binding in the com10 mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:8617–8623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AD, Redfield RJ. Non-canonical CRP sites control competence regulons in Escherichia coli and many other gamma-proteobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6001–6014. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caster JH, Goodgal SH. Competence Mutant of Haemophilus influenzae with abnormal Ratios of Marker Efficiencies in Transformation. J. Bacteriol. 1972;112:492–502. doi: 10.1128/jb.112.1.492-502.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caster JH, Postel EH, Goodgal SH. Competence mutants: isolation of transformation-deficient strains of Haemophilus influenzae. Nature. 1970;227:515–517. doi: 10.1038/227515a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MS. The gene encoding cAMP receptor protein is required for competence development in Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:1626–1630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MS, Smith RA. Characterization of the Haemophilus influenzae topA locus: DNA topoisomerase I is required for genetic competence. Gene. 1996;169:25–31. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00777-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen I, Dubnau D. DNA uptake during bacterial transformation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:241–249. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen I, Christie PJ, Dubnau D. The ins and outs of DNA transfer in bacteria. Science. 2005;310:1456–1460. doi: 10.1126/science.1114021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton SW, McCarthy D, Roe BA. Sequence of the rec-2 locus of Haemophilus influenzae: homologies to comE-ORF3 of Bacillus subtilis and msbA of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1994;146:95–100. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90840-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concino MF, Goodgal SH. DNA-binding vesicles released from the surface of a competence-deficient mutant of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 1982;152:441–450. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.1.441-450.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz R, Ghofaily LA, Patel J, Balashova NV, Freitas AC, Labib I, Kachlany SC. Characterization of leukotoxin from a clinical strain of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Microb. Pathog. 2006;40:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorocicz IR, Williams PM, Redfield RJ. The Haemophilus influenzae adenylate cyclase gene: cloning, sequence, and essential role in competence. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:7142–7149. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7142-7149.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty BA, Smith HO. Identification of Haemophilus influenzae Rd transformation genes using cassette mutagenesis. Microbiology. 1999;145:401–409. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-2-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubnau D. DNA uptake in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1999;53:217–244. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastcott JW, Taubman MA, Smith DJ, Holt SC. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans mitogenicity for B cells can be attributed to lipopolysaccharide. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 1990;5:8–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1990.tb00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine DH, Furgang D, Schreiner HC, Goncharoff P, Charlesworth J, Ghazwan G, Fitagerald-Bocarsly P, Figurski DH. Phenotypic variation in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans during laboratory growth: implications for virulence. Microbiology. 1999;145:1335–1347. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine DH, Velliyagounder K, Furgang D, Kaplan JB. The Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans autotransporter adhesin Aae exhibits specificity for buccal epithelial cells from humans and old world primates. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:1947–1953. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.1947-1953.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine DH, Kaplan JB, Kachlany SC, Schreiner HC. How we got attached to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: A model for infectious diseases. Periodontol. 2000. 2006;42:114–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fives-Taylor PM, Meyer DH, Mintz KP, Brissette C. Virulence factors of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Periodontol. 2000. 1999;20:136–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujise O, Lakio L, Wang Y, Asikainen S, Chen C. Clonal distribution of natural competence in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2004;19:340–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.2004.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürste JP, Pansegrau W, Frank R, Blöcker H, Scholz P, Bagdasarian M, Lanka E. Molecular cloning of the plasmid RP4 primase region in a multi-host-range tacP expression vector. Gene. 1986;48:119–131. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli DM, Polan-Curtain JL, LeBlanc DJ. Structural and segregational stability of various replicons in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Plasmid. 1996;36:42–48. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli DM, Chen J, Novak KF, Leblanc DJ. Nucleotide sequence and analysis of conjugative plasmid pVT745. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:1585–1594. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.5.1585-1594.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncharoff P, Yip JK, Wang H, Schreiner HC, Pai JA, Furgang D, Stevens RH, Figurski DH, Fine DH. Conjugal transfer of broad-host-range incompatibility group P and Q plasmids from Escherichia coli to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect. Immun. 1993;61:3544–3547. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3544-3547.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SD, Scocca JJ. Identification and arrangement of the DNA sequence recognized in specific transformation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988;85:6982–6986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromkova R, Goodgal S. Uptake of plasmid deoxyribonucleic acid by Haemophilus. J. Bacteriol. 1981;146:79–84. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.1.79-84.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryczan T, Contente S, Dubnau D. Molecular cloning of heterologous chromosomal DNA by recombination between a plasmid vector and a homologous resident plasmid in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1980;177:459–467. doi: 10.1007/BF00271485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwinn ML, Yi D, Smith HO, Tomb JF. Role of the two-component signal transduction and the phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems in competence development of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:6366–6368. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6366-6368.1996. Erratum in J. Bacteriol. 179, 567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwinn ML, Stellwagen AE, Craig NL, Tomb JF, Smith HO. In vitro Tn7 mutagenesis of Haemophilus influenzae Rd and characterization of the role of atpA in transformation. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:7315–7320. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7315-7320.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwinn ML, Ramanathan R, Smith HO, Tomb JF. A new transformation-deficient mutant of Haemophilus influenzae Rd with normal DNA uptake. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:746–748. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.746-748.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Microbial etiological agents of destructive periodontal diseases. Periodontol. 2000. 1994;5:78–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1994.tb00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton HL, Dillard JP. Natural transformation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: from DNA donation to homologous recombination. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;59:376–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison SC, Aggarwal AK. DNA recognition by proteins with the helix-turn-helix motif. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1990;59:933–969. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.004441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubek D, Poulsen K, Asikainen S, Kilian M. Evidence for absence in northern Europe of especially virulent clonal types of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Clinical Microbiol. 1995;33:395–401. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.395-401.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson B, Nair SP, Ward JM, Wilson M. Molecular pathogenicity of the oral opportunistic pathogen Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;57:29–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt SC, Tanner AC, Socransky SS. Morphology and ultrastructure of oral strains of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Haemophilus aphrophilus. Infect. Immun. 1980;30:588–600. doi: 10.1128/iai.30.2.588-600.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Tanimoto I, Ohta H, Kato K, Murayama Y, Fukui K. Molecular characterization of low-molecular-weight component protein, Flp, in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans fimbriae. Microbiol. Immunol. 1998;42:253–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1998.tb02280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye T, Ohta H, Kokeguchi S, Fukui K, Kato K. Colonial variation and fimbriation of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1990;57:13–17. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90405-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn ME, Barany F, Smith HO. Transformasomes: specialized membranous structures that protect DNA during Haemophilus transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1983;80:6927–6931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.22.6927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachlany SC, Planet PJ, Bhattacharjee MK, Kollia E, DeSalle R, Fine DH, Figurski DH. Nonspecific adherence by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans requires genes widespread in bacteria and archaea. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:6169–6176. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.21.6169-6176.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachlany SC, Planet PJ, DeSalle R, Fine DH, Figurski DH. Genes for tight adherence of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: from plaque to plague to pond scum. Trends Microbiol. 2001a;9:429–437. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachlany SC, Planet PJ, DeSalle R, Fine DH, Figurski DH, Kaplan JB. flp-1, the first representative of a new pilin gene subfamily, is required for non-specific adherence of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Mol. Microbiol. 2001b;40:542–554. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JB, Schreiner HC, Furgang D, Fine DH. Population structure and genetic diversity of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans strains isolated from localized juvenile periodontitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002;40:1181–1187. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.4.1181-1187.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JB, Velliyagounder K, Ragunath C, Rohde H, Mack D, Knobloch JK, Ramasubbu N. Genes involved in the synthesis and degradation of matrix polysaccharide in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:8213–8220. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.24.8213-8220.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karudapuram S, Barcak GJ. The Haemophilus influenzae dprABC genes constitute a competence inducible operon that requires the product of the tfoX (sxy) gene for transcriptional activation. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:4815–4820. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4815-4820.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodrubetz D, Dailey T, Ebersole J, Kraig E. Cloning and expression of the leukotoxin gene from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect. Immun. 1989;57:1465–1469. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.5.1465-1469.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodrubetz D, Kraig E. Transposon Tn5 mutagenesis of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans via conjugation. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 1994;9:290–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1994.tb00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooistra J, van Boxel T, Venema G. Characterization of a conditionally transformation-deficient mutant of Haemophilus influenzae that carries a mutation in the rec-1 gene region. J. Bacteriol. 1983;153:852–860. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.2.852-860.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll JS, Wilks KE, Farrant JL, Langford PR. Natural genetic exchange between Haemophilus and Neisseria: intergeneric transfer of chromosomal genes between major human pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:12381–12385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lally ET, Golub EE, Kieba IR, Taichman NS, Rosenbloom J, Rosenbloom JC, Gibson CW, Demuth DR. Analysis of the Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin gene. Delineation of unique features and comparison to homologous toxins. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:15451–15456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson TG, Goodgal SH. Sequence and transcriptional regulation of com101A, a locus required for genetic transformation in Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:4683–4691. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4683-4691.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz MG, Wackernagel W. Bacterial gene transfer by natural genetic transformation in the environment. Microbiol. Rev. 1994;58:563–602. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.563-602.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Redfield RJ. Point mutations in a peptidoglycan biosynthesis gene cause competence induction in Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:3323–3330. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.12.3323-3330.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfadyen LP. Regulation of competence development in Haemophilus influenzae. J. Theor. Biol. 2000;207:349–359. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan DF, Taichman NS, Lally ET, Wahl SM. Lethal effects of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin on human T lymphocytes. Infect. Immun. 1991;59:3267–3272. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3267-3272.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan SK, Nagaraja TG, Chengappa MM, Stewart GC. Leukotoxins of gram-negative bacteria. Vet. Microbiol. 2002;84:337–356. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(01)00467-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norskov-Lauritsen N, Kilian M. Reclassification of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Haemophilus aphrophilus, Haemophilus paraphrophilus and Haemophilus segnis as Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans gen. nov., comb. nov., Aggregatibacter aphrophilus comb. nov. and Aggregatibacter segnis comb. nov., and amended description of Aggregatibacter aphrophilus to include V factor-dependent and V factor-independent isolates. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006;56:2135–2146. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notani NK, Setlow JK, Joshi VR, Allison DP. Molecular basis for the transformation defects in mutants of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 1972;110:1171–1180. doi: 10.1128/jb.110.3.1171-1180.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paturel L, Casalta JP, Habib G, Nezri M, Raoult D. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans endocarditis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2004;10:98–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez BA, Planet PJ, Kachlany SC, Tomich M, Fine DH, Figurski DH. Genetic analysis of the requirement for flp-2, tadV, and rcpB in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:6361–6375. doi: 10.1128/JB.00496-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planet PJ, Kachlany SC, Fine DH, DeSalle R, Figurski DH. The Widespread Colonization Island of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:193–198. doi: 10.1038/ng1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt T. Termination of transcription and its regulation in the tryptophan operon of E. coli. Cell. 1981;24:10. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfield RJ. sxy-1, a Haemophilus influenzae mutation causing greatly enhanced spontaneous competence. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:5612–5618. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.18.5612-5618.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfield RJ, Cameron AD, Qian Q, Hinds J, Ali TR, Kroll JS, Langford PR. A novel CRP-dependent regulon controls expression of competence genes in Haemophilus influenzae. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;347:735–747. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfield RJ, Findlay WA, Bosse J, Kroll JS, Cameron AD, Nash JH. Evolution of competence and DNA uptake specificity in the Pasteurellaceae. BMC Evol. Biol. 2006;6:82–96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes ER, Tomaras AP, McGillivary G, Connerly PL, Actis LA. Genetic and functional analyses of the Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans AfeABCD siderophore-independent iron acquisition system. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:3758–3763. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3758-3763.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe BA, Najar FZ, Gillaspy A, Clifton S, Ducey T, Lewis L, Dyer DW. Actinobacillus Genome Sequencing Project. 2006 [online.] http://www.genome.ou.edu/act.html.

- Rosan B, Slots J, Lamont RJ, Listgarten MA, Nelson GM. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans fimbriae. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 1988;3:58–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1988.tb00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Meyer DH, Fives-Taylor PM. Aae, an autotransporter involved in adhesion of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans to epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:2384–2393. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2384-2393.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Takamatsu N, Okahashi N, Matsunoshita N, Inoue M, Takehara T, Koga T. Construction of mutants of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans defective in serotype b-specific polysaccharide antigen by insertion of transposon Tn916. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1992;138:1203–1209. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-6-1203. Erratum in J. Gen. Microbiol. 138, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scannapieco FA, Millar SJ, Reynolds HS, Zambon JJ, Levine MJ. Effect of anaerobiosis on the surface ultrastructure and surface proteins of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (Haemophilus actinomycetemcomitans) Infect. Immun. 1987;55:2320–2323. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2320-2323.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton JA, Vogel JP. Regulation of hypercompetence in Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:3814–3825. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.12.3814-3825.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisco KL, Smith HO. Sequence-specific DNA uptake in Haemophilus transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1979;76:972–976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.2.972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slots J. Addressing antimicrobial resistance threats. Aust. Endod. J. 1999;25:12–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.1999.tb00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets LC, Becker SC, Barcak GJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Bitter W, Goosen N. Functional characterization of the competence protein DprA/Smf in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006;263:223–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HO, Danner BB, Deich RA. Genetic transformation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1981;50:41–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.000353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HO, Gwinn ML, Salzberg SL. DNA uptake signal sequences in naturally transformable bacteria. Res. Microbiol. 1999;150:603–616. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(99)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JL, Bayles DO. The contribution of cytolethal distending toxin to bacterial pathogenesis. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;32:227–248. doi: 10.1080/10408410601023557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreenivasan PK, LeBlanc DJ, Lee LN, Fives-Taylor P. Transformation of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans by electroporation, utilizing constructed shuttle plasmids. Infect. Immun. 1991;59:4621–4627. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4621-4627.1991. Erratum in 1992 Infect. Immun. 60, 1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taichman NS, Wilton JM. Leukotoxicity of an extract from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans for human gingival polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Inflammation. 1981;5:1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00910774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson VJ, Bhattacharjee MK, Fine DH, Derbyshire KM, Figurski DH. Direct selection of IS903 transposon insertions by use of a broad-host-range vector: isolation of catalase-deficient mutants of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:7298–7307. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.23.7298-7307.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomb JF, Barcak GJ, Chandler MS, Redfield RJ, Smith HO. Transposon mutagenesis, characterization, and cloning of transformation genes of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:3796–3802. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3796-3802.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomb JF, el-Hajj H, Smith HO. Nucleotide sequence of a cluster of genes involved in the transformation of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Gene. 1991;104:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90457-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tϕnjum T, Bukholm G, Bϕvre K. Identification of Haemophilus aphrophilus and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans by DNA-DNA hybridization and genetic transformation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990;28:1994–1998. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.1994-1998.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanWagoner TM, Whitby PW, Morton DJ, Seale TW, Stull TL. Characterization of three new competence-regulated operons in Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:6409–6421. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.19.6409-6421.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Winkerhoff AJ, Slots J. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis in nonoral infections. Periodontol. 2000. 1999;20:122–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Goodman SD, Redfield RJ, Chen C. Natural transformation and DNA uptake signal sequences in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:3442–3449. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.13.3442-3449.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Shi W, Chen W, Chen C. Type IV pilus gene homologs pilABCD are required for natural transformation in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Gene. 2003;312:249–255. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00620-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Orvis J, Dyer D, Chen C. Genomic distribution and functions of uptake signal sequences in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Microbiology. 2006;152:3319–3325. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willi K, Sandmeier H, Kulik EM, Meyer J. Transduction of antibiotic resistance markers among Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans strains by temperate bacteriophages Aaϕ23. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1997;53:904–910. doi: 10.1007/s000180050109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams PM, Bannister LA, Redfield RJ. The Haemophilus influenzae sxy-1 mutation is in a newly identified gene essential for competence. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:6789–6794. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.6789-6794.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise EM, Alexander SP, Powers M. Adenosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate as a regulator of bacterial transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1973;70:471–474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss C. Selected low-cohesion variants of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Haemophilus aphrophilus lack distinct antigens recognized by human antibodies. Arch. Microbiol. 1989;151:133–136. doi: 10.1007/BF00414427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambon JJ. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1985;12:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulty JJ, Barcak GJ. Identification of a DNA transformation gene required for com101A+ expression and supertransformer phenotype in Haemophilus influenzae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:3616–3620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]