Abstract

Background

Particulate matter <10 μm (PM10) from fossil fuel combustion is associated with an increased prevalence of respiratory symptoms in children and adolescents. However, the effect of PM10 on respiratory symptoms in young children is unclear.

Methods

The association between primary PM10 (particles directly emitted from local sources) and the prevalence and incidence of respiratory symptoms was studied in a random sample cohort of 4400 Leicestershire children aged 1–5 years surveyed in 1998 and again in 2001. Annual exposure to primary PM10 was calculated for the home address using the Airviro dispersion model and adjusted odds ratios (ORS) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each μg/m3 increase.

Results

Exposure to primary PM10 was associated with the prevalence of cough without a cold in both 1998 and 2001, with adjusted ORs of 1.21 (1.07 to 1.38) and 1.56 (1.32 to 1.84) respectively. For night time cough the ORs were 1.06 (0.94 to 1.19) and 1.25 (1.06 to 1.47), and for current wheeze 0.99 (0.88 to 1.12) and 1.28 (1.04 to 1.58), respectively. There was also an association between primary PM10 and new onset symptoms. The ORs for incident symptoms were 1.62 (1.31 to 2.00) for cough without a cold and 1.42 (1.02 to 1.97) for wheeze.

Conclusion

In young children there was a consistent association between locally generated primary PM10 and the prevalence and incidence of cough without a cold and the incidence of wheeze which was independent of potential confounders.

Keywords: children, particulates, air pollutants, vehicle emissions

There is now a consensus that exposure to particulate matter from the combustion of fossil fuels with a 50% cut off aerodynamic diameter of 10 μm (PM10) exacerbates a range of respiratory conditions in children.1,2 Young children may be especially vulnerable to adverse effects of PM10 since they have a higher minute ventilation relative to lung size,1 a higher prevalence of respiratory symptoms,3 and exhibit qualitative differences in lung growth.4 Indeed, associations between PM10 and respiratory symptoms have been observed in the few studies that have focused on young children. Braun‐Fahrländer et al5 were the first to report an association between the 6 week average concentration of total suspended particulate matter and an increased incidence of coughing episodes in a panel study of preschool children. In a cohort study, Brauer et al6 estimated exposure in the home to PM2.5 in children aged 2 years of age and found a positive but non‐significant association with wheeze and dry cough at night. Using the same methodology, Gehring et al7 found no association between PM10 and parent reported wheeze in children aged 1 and 2 years. To date, no cohort study has examined the association between locally generated PM10 and respiratory symptoms over the whole preschool age range. The benefits of local initiatives aimed at reducing emissions (such as congestion charging) in this vulnerable group are therefore unclear.

PM10 may be categorised either by chemical composition, size (ultrafine to coarse), or origin, with the latter classifying “primary” PM10 as particles emitted directly from combustion sources and “secondary” PM10 as particles formed from the oxidation of sulphur and nitrogen dioxides in the atmosphere.8 In UK cities, direct primary emission of PM10 from local traffic is the most important determinant of variations in individual exposure.9,10,11 Indeed, the proximity of the home to main roads has been used as a marker of individual exposure to the complex mix of gases, volatile organic compounds, and particles emitted by traffic.12,13,14,15 However, distance from the road does not take into account prevailing wind direction or differences in the mix and density of vehicles on main roads. In contrast, dispersion models calculate both the generation of primary PM10 from local sources and its dispersion into adjacent areas, adjusting for wind direction and other meteorological parameters.16,17,18 For example, Leicester City Council (UK) along with several other European cites has, since 1998, used dispersion modelling for traffic planning.19,20

In this study we aimed to determine the association between locally generated primary PM10, calculated using a dispersion model, and the prevalence and incidence of parent reported respiratory symptoms in young children. Respiratory symptom data from a cohort of preschool children surveyed in 1998 and again in 2001 were linked to modelled exposure to locally generated primary PM10 at their home addresses, and evidence for a dose‐response relationship was sought after adjusting for a number of potential confounding factors.

Methods

Study population

A cohort of 4400 children aged 1–5 years was recruited in 1998 from a random sample of the Leicestershire Health Authority Child Health Database. Parents or guardians were sent a respiratory symptom questionnaire in 1998 and again in 2001. On each occasion, two repeat mailings of non‐responders were subsequently sent out at 6 week intervals. The study was approved by the Leicestershire Health Authority ethics committee. Data from a subgroup of children surveyed in 1998 have previously been used in a study of the changing prevalence of preschool wheeze.3

Exposure assessment

Exposure to locally generated primary PM10 was assessed using the Indic‐Airviro dispersion model Version 2.2 (Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute, Norrköping, Sweden). The Leicester City Council's pollution control group uses Airviro to calculate spatial variations in “total” PM10.20 To calculate annual “total” PM10, the concentration of locally emitted “primary” PM10 is first calculated for 50×50 m grids. A uniform concentration, representing “secondary” and “coarse” PM10 imported from other counties (for example, 9.28 μg/m3 for 2001), is then added to the primary PM10 output. In the present study the “primary” output of the model was used since it reflects the variation in PM10 exposure within Leicestershire. The model does not use actual PM10 measurements; rather, it models primary PM10 emissions for roads using traffic flow data and then applies real time wind speed/direction to these data to calculate how these emissions are blown into neighbouring areas. For road emissions the model divides roads into >3500 stretches between main junctions.20 Airviro calculates the concentration of primary PM10 emitted from each road by drawing on a database of updated information on the type of vehicle journeys, average daily traffic flows, speeds, and vehicular mix. Dispersion of emissions is calculated using data of the actual meteorological conditions present at the time.20 To calculate annual exposure of the home address to locally generated primary PM10 (μg/m3), we entered the home coordinates (Address‐point database, Ordnance Survey, Southampton, UK) into the model and obtained 8760 hourly data points for the relevant 50×50 metre grid. The 1998 output was further adjusted to take into account vehicle emission factors updated in 1999. Change of home address during the survey period was identified using the Leicestershire Health Authority Child Health Database which included both the date of move and the new address. Since the Airviro provided hourly concentrations, we could adjust for the date of the move. The model could not be used for the edges of Leicestershire since the number and type of cars on roads in neighbouring counties was not available. For longitudinal exposure assessment, the mean of the 1998 and 2001 exposures was used.

Questionnaire data

Three questions were chosen a priori to derive the primary outcome variables:

“Did your child usually have a cough apart from colds in the last 12 months?” (cough without a cold);21

“In the last 12 months has your child had a dry cough at night, apart from a cough associated with a cold or a chest infection?” (night time cough);3

“Has your child had wheezing or whistling in the chest in the last 12 months?” (current wheeze).3

Covariates were selected from the same questionnaire, either because they were considered to be risk factors of lower respiratory symptoms in children or because they could influence the association between respiratory symptoms and pollution exposure within the cohort.6 Since the spatial distribution of social deprivation and levels of air pollution are closely correlated in the UK,22 we decided a priori not to include a spatially associated measure of deprivation (such as the Townsend score) in the analysis, but adjusted instead for non‐spatial individual measures of socioeconomic status including maternal and paternal education, overcrowding, and single parenthood.

Statistical analysis

The questionnaire data were double entered into EpiInfo software (Version 6.04b, US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA). Subsequent analyses were carried out using SAS Version 8.2 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and S‐plus Version 6.1 (Seattle, WA, USA). Binomial generalised linear models with the logistic link were used in the model examining the association between the primary response variables and local PM10. Exposures were entered both as categorical and linear terms into the model and quadratic and cubic terms were also tested. Using likelihood ratio tests to compare the fit of these different models, none of the alternative models performed better than a linear model. Furthermore, as spatial correlation is a concern in this type of analysis, variograms were used to check both for the responses themselves and the residuals from the models for spatial correlation. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each μg/m3 increase in local primary PM10. Stratified models and interaction tests were used to assess if the effect of PM10 was stronger in children not going to nursery or daycare centres, and in children not exposed to environmental tobacco smoke.

Results

The response rate from parents was 77.7% (3410/4400) in 1998 and 60.8% (2580/4245) in 2001. Between April 1997 and April 2001, 1265 children had moved address once, 438 twice, and 230 more than twice. The mean annual exposure to locally generated PM10 was calculated for 3045 children whose parents responded in 1998, and for 2303 in 2001. Both surveys showed a high prevalence of parent reported respiratory symptoms: for 1998 and 2001, respectively, the prevalence of cough without a cold was 25% and 25%, night time cough 31% and 29%, and current wheeze 25% and 14%. The prevalence of selected characteristics of the study group is shown in table 1.

Table 1 Prevalence of selected characteristics of the study population surveyed in 1998 and in 2001.

| Variable | n* | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in 1998 survey (years)† | ||

| 1.0–1.99 | 1085 | 25 |

| 2.0–2.99 | 1099 | 25 |

| 3.0–3.99 | 1113 | 25 |

| 4.0–4.99 | 1102 | 25 |

| Boys | 2304 | 52 |

| Girls | 2095 | 48 |

| Mother has asthma | 554 (3203) | 17 |

| Coal heating in the home | ||

| 1998 | 203 (3410) | 6 |

| 2001 | 199 (2735) | 7 |

| Smoking by household member in the home | ||

| 1998 | 1144 (3382) | 34 |

| 2001 | 793 (2543) | 31 |

| Either parent continued education past 16 years of age | 1986 (3012) | 66 |

*Number of children (total of replies in each category).

†A total of 4400 children were selected for the survey in 1998.

Other covariates examined were preterm birth, breast feeding, father with asthma, gas cooking, presence of pets, number of cigarettes smoked by mother, overcrowding, single parenthood, and diet.

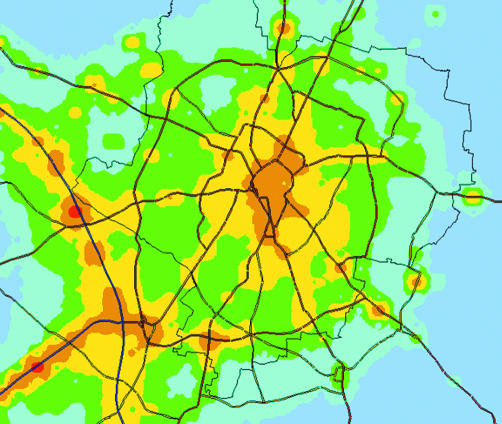

The output of Airviro confirmed that primary PM10 was increased along local emission sources such as main roads (fig 1). Overall, the annual mean (25–75th percentile) primary PM10 concentration for the cohort was 1.47 (0.73–1.93) μg/m3 in 1998 and 1.33 (0.8–1.84) μg/m3 in 2001.

Figure 1 Map of annual mean total PM10 for Leicester calculated using the Airviro dispersion model. The spectrum ranges from blue (low) to green, yellow, orange and red (high). These spatial differences are due to differences in locally generated primary PM10. Areas of high exposure and heavily used roads. © Crown copyright Ordnance Survey, all rights reserved (NC/01/504).

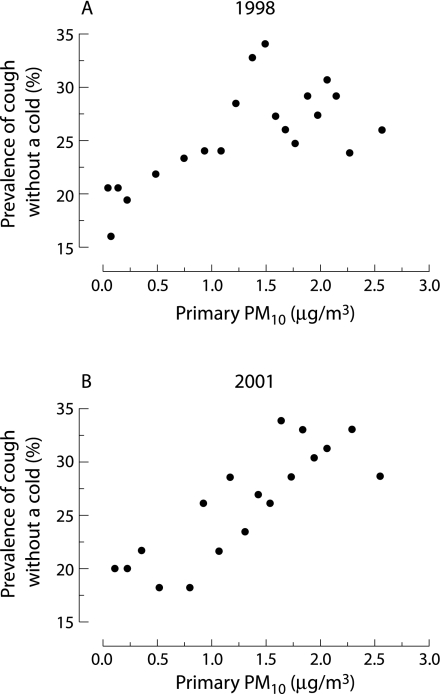

After adjusting for confounders, exposure to locally generated PM10 was associated with an increased prevalence of cough without a cold in both the 1998 and 2001 surveys (table 2), with evidence of a dose‐response effect (fig 2). For prevalence of night time cough the ORs were slightly lower in both surveys. Current wheeze was not associated with PM10 before adjusting for confounders (table 2). After adjustment there was a positive association in 2001 (table 2). The effect of PM10 on health outcomes did not depend on whether or not children were exposed to environmental tobacco smoke or went to nursery care (all interaction tests with p>0.1).

Table 2 Association between mean annual exposure of the home address to locally generated primary PM10 and prevalence of respiratory symptoms in young children.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR† | 95% CI | n‡ | OR† | 95% CI | n‡ | |

| Cough without a cold | ||||||

| 1998 | 1.22 | 1.10 to 1.36 | 2567 | 1.21 | 1.07 to 1.38 | 2164 |

| 2001 | 1.46 | 1.27 to 1.68 | 2301 | 1.56 | 1.32 to 1.84 | 1756 |

| Night time cough | ||||||

| 1998 | 1.11 | 1.01 to 1.23 | 2579 | 1.06 | 0.94 to 1.19 | 2174 |

| 2001 | 1.25 | 1.09 to 1.43 | 2318 | 1.25 | 1.06 to 1.47 | 1771 |

| Current wheeze | ||||||

| 1998 | 0.99 | 0.89 to 1.10 | 2584 | 0.99 | 0.88 to 1.12 | 2175 |

| 2001 | 1.09 | 0.93 to 1.30 | 2331 | 1.28 | 1.04 to 1.58 | 1774 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

*Adjusted for confounding variables in table 1.

†Per μg/m3 increase in locally generated primary PM10.

‡Number of responses.

Figure 2 Scatterplots of the relationship between annual exposure to locally generated PM10 at the home address expressed as μg/m3 and prevalence of cough without a cold surveys undertaken in (A) 1998 and (B) 2001 of a random stratified sample of 1–5 year old children in Leicestershire, UK. Each data point represents five centiles of unadjusted data sorted by exposure (n = 128 in 1998 and n = 115 in 2001).

We analysed the association between mean exposure to PM10 from 1998 to 2001 and incident symptoms in children who were initially asymptomatic (table 3). There was a strong association between PM10 and adjusted incident cough without a cold, and somewhat weaker associations with incident wheeze and incident night cough (table 3). Analysis by age did not show evidence for an effect modification, with adjusted ORs for cough without a cold of 1.51 (1.12 to 2.04) in children aged 1–2.99 years and 1.71 (1.26 to 2.31) in children aged 3–4.99 years. For night cough, the ORs for younger and older children were 1.24 (0.94 to 1.66) and 1.14 (0.83 to1.55) respectively, and for wheeze 1.43 (0.91 to 2.26) and 1.39 (0.86 to 2.25). We found no association between PM10 and persistence of symptoms in children who were symptomatic in 1998 (data not shown), but statistical power for this analysis was very low (numbers of children in the adjusted models for persistence of symptoms were n = 406 for cough without a cold, n = 466 for night cough, and n = 221 for wheeze).

Table 3 Association between exposure of the home address to locally generated primary PM10 and incident cough and wheeze (defined as not present in the 1998 survey and present in the 2001 survey versus no symptoms in both surveys).

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR† | 95% CI | n‡ | OR† | 95% CI | n‡ | |

| Cough without a cold | 1.68 | 1.39 to 2.03 | 1479 | 1.62 | 1.31 to 2.00 | 1287 |

| Night time cough | 1.21 | 1.00 to 1.46 | 1382 | 1.19 | 0.96 to 1.47 | 1191 |

| Wheeze | 1.22 | 0.92 to 1.62 | 1533 | 1.42 | 1.02 to 1.97 | 1319 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

*Adjusted for confounding variables in table 1.

†Per μg/m3 increase in locally generated primary PM10.

‡Number of responses.

Discussion

Using a dispersion model to estimate differences in exposure of homes of young children to locally generated primary PM10, we found a strong association between exposure and the prevalence and incidence of cough without a cold and night cough which was independent of potential confounders. Furthermore, there was clear evidence for a dose‐response relationship. The evidence for an association between primary PM10 and the prevalence and incidence of current wheeze was less consistent. These data are compatible with a German cohort study which estimated PM exposure at the home address of children at 1 year of age and reported ORs of 1.43 for cough without infection and 1.39 for dry cough at night for each 1.5 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5.7 Our study extends these data by showing that the association with cough is present across the preschool age range. By 2001 some of the children in our cohort had reached school age. In this older age group the published evidence for an association between PM10 and cough is conflicting. The 12 Community Southern California cohort study23 found no association between PM10 and cough. In contrast, Braun‐Fahrländer et al24 reported a strong significant association between PM10 and both chronic and nocturnal dry cough in a cross sectional survey of 4470 Swiss children aged 6–15 years. Further surveys of the Leicester cohort should help to clarify whether this association continues throughout childhood.

Although we found that PM10 was associated with the prevalence of cough without a cold, and there was a strong association with incident cough in children who were asymptomatic in the 1998 survey, we did not assess whether this type of cough affected the quality of life of children and their parents. However, preschool cough is not necessarily a trivial condition, as indicated by a recent study of Leicestershire general practitioners which reported that preschool children attending with “non‐asthmatic” cough suffered significant sleep disruption and decreased activity levels.25 Unfortunately, we did not have the information to quantify children with cough into groups of different severity.

The association between modelled PM10 exposure and wheeze was inconsistent between surveys—that is, while there was no association with prevalent wheeze in 1998, there was evidence for an association with prevalent wheeze in 2001. Similarly, there is no consistency in the published studies on PM10 and prevalence of wheezing disorders in children. On the one hand, Nicolai et al26 reported an increased prevalence of current wheeze (adjusted OR 1.66) in children aged 9–11 years living within 50 metres of roads with high traffic flows, and Venn et al12 found an increased prevalence of wheeze in a subgroup of a UK cohort of children aged 4–11 years living within 150 metres of a main road. On the other hand, other population based cohort studies have found no significant effect of PM10 on current wheeze.6,23,24,27 Indeed, the most recent study of young school age children28 found no association between living near a main road and the prevalence of asthma. In preschool children, Edwards et al29 reported that children admitted to hospital with asthma were more likely to live in areas of high traffic flow (compared with those admitted for non‐respiratory reasons), and it is possible that parent reported wheeze is an imprecise descriptor of preschool asthma. Alternatively, modelled local primary PM10 may not reflect the size or composition of particles that upregulate cellular mechanisms associated with wheeze. However, we did find an association between primary PM10 and new onset (incident) wheeze in 2001, which supports the speculation that early exposure to PM10 may play a causal role in the development of asthma, especially in children with a genetic predisposition to attenuated antioxidant defences.30 Further study of our cohort will be required to establish if new onset wheezing in the 2001 survey is atopic asthma, and if it is associated with mutations in the genes involved in the induction of pulmonary antioxidant defence.30

There are important limitations to our study. Although PM10 is a biologically plausible mediator of health effects,31 causation cannot be assumed. Fossil fuel particles do, however, penetrate into the airways of children. In a previous study we found aggregates of carbonaceous nanoparticles (<0.01 μm2) in alveolar macrophages from healthy infants and children living in Leicestershire.32 There is debate about the size fraction of PM10 responsible for health effects, with speculation that nanoparticles are the most damaging.31 In European cities where traffic is the major source of PM10, there is a close correlation between nanoparticle number and PM10 concentration.33 It is therefore likely that modelled primary PM10 reflects exposure to traffic associated nanoparticles, but not necessary to larger “coarse” particles (PM2.5–10) which are mostly derived from soil and sea salts.30

A second limitation of the study is that there may be an unrecognised confounding variable with a high spatial correlation with traffic pollution, especially one associated with poor socioeconomic status. Indeed, compatible with UK data,22 we found a significant correlation between modelled exposure to primary PM10 and Townsend score (r = 0.41 in 1998, and r = 0.45 in 2001, p<0.0001). Thus, adjusting our data for a spatial measure of deprivation would have resulted in an underestimation of the effect of PM10. For example, the association between PM10 exposure and cough without a cold in 2001 fell from 1.56 to 1.42 (1.18 to 1.72) when the Townsend score was included as a confounding variable.

Thirdly, we did not estimate the effect of “imported” PM10 blown into Leicestershire from other counties and countries. Imported particles may also affect respiratory health, but we could not detect this since concentrations would be close to uniform over the spatial area of the cohort over a 12 month period. Fourthly, although Airviro performs well in modelling the spatial distribution of traffic associated carbon monoxide16 which in turn is a valid marker for traffic associated PM10,34 we did not validate modelled data by direct measurement. Finally, any estimate of PM10 at the home address can only approximate individual exposure. We did not record time‐activity data, but had recorded whether children attended a nursery. The strength of association between PM10 and the health outcomes did not differ whether or not the children went to nursery care. One explanation is that the total time spent in nursery per week is negligible compared with the time spent at or around home in this age group.

In summary, in a cohort of young children we found a consistent association between exposure to locally emitted primary PM10 and the prevalence and incidence of cough without a cold and night time cough, and incidence of wheeze. We conclude that a reduction in locally generated primary PM10 may have significant health benefits in young children, and that linking paediatric cohort data to pollution dispersion models may help in planning local air quality initiatives.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Catherine Mallon, Adrian Russell and Neil Cooper of the Leicester City Council for the Airviro analysis, Adrian Brooke for helpful discussions, and Tony Davies of Leicestershire Health for help in accessing the Leicestershire Health Authority Child Health Database.

Footnotes

Nevil Pierse was supported by a grant from the UK Department of Health (number 0020014). Claudia Kuehni was supported the Swiss National Science Foundation (PROSPER grant number 3233‐069348 and 3200‐069349, and SNF grant 823B ‐ 046481). Recruitment of the cohort and initial data collection was funded by a research grant from Trent NHS Executive (Trent Research Scheme, RBF number 98XX3). Support was also provided by Medisearch (UK) and University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust Department of Research and Development.

Competing interests: none declared.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Environmental Health Air pollutants, outdoor. In: Etzel RA, Balk SJ, eds. Pediatric environmental health. EIR Grove, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 200369–86.

- 2.Kunzli N, Kaiser R, Medina S.et al Public‐health impact of outdoor and traffic‐related air pollution: a European assessment. Lancet 2000356795–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuehni C E, Davis A, Brooke A M.et al Are all wheezing disorders in very young (preschool) children increasing in prevalence? Lancet 20013571821–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeltner T B, Burri P H. The postnatal development and growth of the human lung. II. Morphology. Respir Physiol 198767269–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun‐Fahrlander C, Ackermann‐Liebrich U, Schwartz J.et al Air pollution and respiratory symptoms in preschool children. Am Rev Respir Dis 199214542–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brauer M, Hoek G, van Vliet P.et al Air pollution from traffic and the development of respiratory infections and asthmatic and allergic symptoms in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20021661092–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gehring U, Cyrys J, Sedlmeir G.et al Traffic‐related air pollution and respiratory health during the first 2 yrs of life. Eur Respir J 200219690–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holman C. Sources of air pollution. In: Holgate S, Samet JM, Koren HS, et al, eds. Air pollution and health. London: Academic Press, 1999115–148.

- 9.Brauer M, Hoek G, van Vliet P.et al Estimating long‐term average particulate air pollution concentrations: application of traffic indicators and geographic information systems. Epidemiology 200314228–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu Y, Hinds W C, Kim S, Sioutas C. Concentration and size distribution of ultrafine particles near a major highway. J Air Waste Manag Assoc 2002521032–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hitchins J, Morawska L, Wolff W.et al Concentrations of submicrometre particles from vehicle emissions near a major road. Atmos Environ 20003451–59. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venn A J, Lewis S A, Cooper M.et al Living near a main road and the risk of wheezing illness in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20011642177–2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilhelm M, Ritz B. Residential proximity to traffic and adverse birth outcomes in Los Angeles County, California, 1994–1996. Environ Health Perspect 2003111207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J J, Smorodinsky S, Lipsett M.et al Traffic‐related air pollution near busy roads: the East Bay Children's Respiratory Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004170520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venn A, Lewis S, Cooper M.et al Local road traffic activity and the prevalence, severity, and persistence of wheeze in school children: combined cross sectional and longitudinal study. Occup Environ Med 200057152–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukherjee P, Viswanathan S. Carbon monoxide modeling from transportation sources. Chemosphere 2001451071–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukherjee P, Viswanathan S, Cheng C L. Modeling mobile source emissions in presence of stationary sources. J Hazard Mater 20007623–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellander T, Berglind N, Gustavsson P.et al Using geographic information systems to assess individual historical exposure to air pollution from traffic and house heating in Stockholm. Environ Health Perspect 2001109633–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anon Heathier Environment through Abatement of Vehicle Emission and Noise: Final Report. Available at http://heaven.rec.org/Deliverables/HEAVEN‐Final%20ReportFull.pdf (accessed January 2006)

- 20.Pollution Control Group Leicester air quality review and assessment 2000. Final report. Available at http://www.leicester.gov.uk/index.asp?pgid = 1486 (accessed January 2006)

- 21.Luyt D K, Burton P R, Simpson H. Epidemiological study of wheeze, doctor diagnosed asthma, and cough in preschool children in Leicestershire. BMJ 19933061386–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pye S, Stedman J, Adams M.et alFurther analysis of NO2 and PM10 air pollution and social deprivation. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, The National Assembly of Wales, and Department of the Environment in Northern Ireland 2001. Available at http://www.aeat.co.uk/netcen/airquality/reports/strategic policy/2001 socialdeprivation_v4.pdf (Accessed January 2006)

- 23.Peters J M, Avol E, Navidi W.et al A study of twelve Southern California communities with differing levels and types of air pollution. I. Prevalence of respiratory morbidity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999159760–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun‐Fahrländer C, Vuille J C, Sennhauser F H.et al Respiratory health and long‐term exposure to air pollutants in Swiss schoolchildren. Am J Respir Crit. Care Med 19971551042–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hay A D, Wilson A, Fahey T.et al The duration of acute cough in pre‐school children presenting to primary care: a prospective cohort study. Fam Pract 200320696–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicolai T, Carr D, Weiland S K.et al Urban traffic and pollutant exposure related to respiratory outcomes and atopy in a large sample of children. Eur Respir J 200321956–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dockery D W, Speizer F E, Stram D O.et al Effects of inhalable particles on respiratory health of children. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989139587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis S A, Antoniak M, Venn A J.et al Secondhand smoke, dietary fruit intake, road traffic exposures, and the prevalence of asthma: a cross‐sectional study in young children. Am J Epidemiol 2005161406–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edwards J, Walters S, Griffiths R K. Hospital admissions for asthma in preschool children: relationship to major roads in Birmingham, United Kingdom. Arch Environ Health 199449223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nel A. Atmosphere. Air pollution‐related illness: effects of particles, Science 2005308804–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donaldson K, MacNee W. Potential mechanisms of adverse pulmonary and cardiovascular effects of particulate air pollution (PM10). Int J Hyg Environ Health 2001203411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bunn H J, Dinsdale D, Smith T.et al Ultrafine particles in alveolar macrophages from normal children. Thorax 200156932–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pekkanen J, Timonen K L, Ruuskanen J.et al Effects of ultrafine and fine particles in urban air on peak expiratory flow among children with asthmatic symptoms. Environ Res 19977424–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ebelt S, Brauer M, Cyrys J.et al Air quality in postunification Erfurt, East Germany: associating changes in pollutant concentrations with changes in emissions. Environ Health Perspect 2001109325–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]