Abstract

Pointing by monkeys, apes, and human infants is reviewed and compared. Pointing with the index finger is a species-typical human gesture, although human infants exhibit more whole-hand pointing than is commonly appreciated. Captive monkeys and feral apes have been reported to only rarely “spontaneously” point, although apes in captivity frequently acquire pointing, both with the index finger and with the whole hand, without explicit training. Captive apes exhibit relatively more gaze alternation while pointing than do human infants about 1 year old. Human infants are relatively more vocal while pointing than are captive apes, consistent with paralinguistic use of pointing.

By 14 months of age, most humans exhibit the capacity to obtain the visual attention of another being and to redirect that individual’s attention to distal objects, locations, or events of interest by pointing (Adamson & Bakeman, 1991; Bates, Camaioni, & Volterra, 1975; Butterworth, 1998). For many years, this capacity was widely considered to be a uniquely human trait (Butterworth & Grover, 1988; Donald, 1991; Werner & Kaplan, 1963). Pointing, by virtue of its referential function, has been characterized as a kind of behavioral stepping-stone to symbolic reference (Bates et al., 1975; Butterworth, 1998). The production and comprehension of pointing in humans may provide a bridge between words and their referents, helping children to associate a particular verbal label with a particular object (Horne & Lowe, 1996). Scrutiny of pointing by humans’ nearest living relatives, apes and monkeys, may have considerable relevance to understanding the evolution of communicative skills in contexts of joint attention to distal objects or events. Yet, no systematic comparative review of pointing behavior by primates, including humans, exists (see Krause, 1997, for review of rearing history effects on pointing).

The development of communicative pointing with outstretched fingers by apes occurs commonly in captivity. Several reports also exist of pointing by monkeys. To date, as listed in Table 1, pointing has been reportedly exhibited by at least 15 captive monkeys, 83 captive apes, and 1 feral ape (Veà & Sabater-Pi, 1998), including New World monkeys (Cebus apella), Old World monkeys (Macaca mulatta, M. fuscata), and representatives of all four great ape species, including orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus), gorillas (Gorilla gorilla), bonobos (Pan paniscus), and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Although the majority of pointing reported in the literature is emitted in the presence of human observers, there are several reports of pointing used as a communicative gesture between apes (de Waal, 1982; Savage-Rumbaugh, 1986; Savage-Rumbaugh, Wilkerson, & Bakeman, 1977; Tomasello, George, Kruger, Farrar, & Evans, 1985; Veà & Sabater-Pi, 1998). That pointing by apes is communicative is established by the effects of audience on pointing by apes: They do not point, or point much less frequently, when an observer is absent or looking away from the pointing individual (Call & Tomasello, 1994; Krause & Fouts, 1997; Leavens, Hopkins, & Bard, 1996). Similar audience effects have been reported for capuchin monkeys (Mitchell & Anderson, 1997) and rhesus monkeys (Blaschke & Ettlinger, 1987).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Pointing by Apes and Monkeys

| Species and study | N | Point to self | Point to other social agent | Point to distal food | Point to distal location, object, or event | Rearing history | Attention-getting? | Alternate gaze? | Index finger? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cebus apella (capuchin monkey) | |||||||||

| Mitchell & Anderson, 1997 | 3 | X | (W, C)/(H, M)/NL? | X | X | ||||

| Macaca mulatta (rhesus macaque) | |||||||||

| Blaschke & Ettlinger, 1987 | 4 | X | ?/?/NL? | No | |||||

| Povinelli, Parks, & Novak, 1992a | 4 | X | ?/?/NL? | ||||||

| Hess, Novak, & Povinelli, 1993 | 1 | X | ?/?/NL? | ||||||

| Macaca fuscata (Japanese macaque) | |||||||||

| Silberberg & Fujita, 1996a | 3 | X | ?/?/NL? | ||||||

| Pongo pygmaeus (orangutan) | |||||||||

| Furness, 1916 | 1 | X | W/M/L | n/a | |||||

| Miles, 1990 | 1 | X | X | X | X | C/D/L | X | X | X |

| Gómez & Teixidor, 1992 | 1 | X | X | W/D/NL | No | X | |||

| Call & Tomasello, 1994 | 1* | X | X | C/(M, D)/(L, NL) | X | X | |||

| Gorilla gorilla (gorilla) | |||||||||

| Patterson, 1978 | 1 | X | X | X | X | C/D/L | |||

| Pan paniscus (bonobo) | |||||||||

| Savage-Rumbaugh, Wilkerson, & Bakeman, 1977b | 3 | X | X | W/M/NL | X | X | ? | ||

| Savage-Rumbaugh, 1984, 1986 | 1 | X | X | C/D/L | X | X | |||

| Veà & Sabater-Pi, 1998b | 1 | X | Feral | X | X | Xc | |||

| Pan troglodytes (chimpanzee) | |||||||||

| Furness, 1916 | 1 | X | W/M/L | n/a | |||||

| Kellogg & Kellogg, 1933 | 1 | X | X | X | C/H/L | X | X | X | |

| Hayes & Hayes, 1954 | 1 | X | C/H/L | X | |||||

| Gardner & Gardner, 1971 | 1 | X | X | X | W/H/L | X | |||

| Terrace, 1979 | 1 | X | X | X | C/H/L | X | |||

| Woodruff & Premack, 1979 | 4 | X | X | W/N/NL | X | ||||

| Fouts, Hirsch, & Fouts, 1982 | 1 | X | X | X | C/N?/L | X | X | ||

| de Waal, 1982b | 1+ | X | ?/?/NL | X | X | ||||

| Tomasello, George, Kruger, Farrar, & Evans, 1985b | 1 | X | C/N/NL | n/a | X | ||||

| Savage-Rumbaugh, 1986b | 2 | X | C/H/L | X | X | ||||

| Boysen & Berntson, 1989 | 1 | X | X | C/H/NL | |||||

| Povinelli, Nelson, & Boysen, 1990 | 3* | X | X | ?/?/NL | |||||

| Leavens, Hopkins, & Bard, 1996 | 3 | X | X | X | C/(M, N)/NL | X | X | X | |

| Krause & Fouts, 1997 | 2 | X | X | C/H/L | X | X | X | ||

| Whiten, in press | 1 | X | C/H/L | X | |||||

| Leavens & Hopkins, 1998 | 50* | X | (C, ?)/(M, N)/NL | X | X | X | |||

| Total | 99+ |

Note. Blank cells indicate the behavior was not reported. Asterisks denote studies that included some individuals also reported to point in previous studies listed; thus, the number reported above reflects the number of individuals first reported to point in marked studies, not the total number of pointing individuals in these marked studies. X = the behavior occurred at least once in the study cited; W = caught in the wild; C = born in captivity; H = home-reared by humans (includes some laboratory settings); M = mother-reared (includes adoptive conspecific mothers); NL = non-language-trained; ? = indeterminable or unknown; L = language-trained; n/a = not applicable; D = initially mother-reared, then human-reared; N = nursery-reared.

Authors used terms reach and point interchangeably.

Pointing reported in these studies was during communication between apes; all other studies involved pointing by apes or monkeys for human observers.

Pointing involved extension of index and ring fingers.

Intentional communication, as denned by developmental researchers, is behaviorally indexed by (a) “attention-getting” behaviors; (b) gaze alternation between an observer and a distal object or event of interest; and (c) persistence until reward, or goal directedness (Bard, 1992; Bates et al., 1975; Sugarman, 1984). Attention-getting behaviors and either gaze monitoring of an addressee or gaze alternation between an addressee and a distal object or event of interest are commonly reported as accompanying pointing behavior in apes. Among monkeys, a rhesus monkey has been reported to vocalize while pointing (Blaschke & Ettlinger, 1987), and a capuchin monkey has been reported to point with gaze monitoring of an experimenter (Mitchell & Anderson, 1997). Leavens et al. (1996) reported measures of persistence in nonhumans that point. They found that 3 chimpanzee subjects exhibited more additional points after an initial point had not been reinforced with delivery of the indicated food items than after the initial point had been reinforced with delivery of the food items. By these objective criteria, then, pointing by apes, and possibly some monkeys, is characterized as an intentionally communicative gesture.

As noted by Call and Tomasello (1994), the vast majority of pointing by apes is reported to be “spontaneous”; that is, it develops in the absence of explicit training to point. There have been two reports of spontaneous pointing by monkeys: a capuchin monkey and a rhesus monkey (Hess, Novak, & Povinelli, 1993; Mitchell & Anderson, 1997). Perhaps because pointing, per se, has not received experimental scrutiny until quite recently—reports being generally descriptive or anecdotal in nature—it has been widely held that monkeys and apes do not point (e.g., Petitto, 1988) and that chimpanzees do not point with the index finger (e.g., Povinelli & Davis, 1994). Because pointing has been defined with reference to human (Homo sapiens) behavior, a review of the development of pointing in humans is warranted. These behaviors are then compared with pointing by chimpanzees, because chimpanzees constitute, by far, the most studied captive ape with respect to their pointing behavior (Table 1). This review reveals several previously unappreciated patterns: (a) Young humans frequently point with the whole hand, (b) chimpanzees often point with the index finger, (c) chimpanzees exhibit more gaze alternation while pointing than do young humans, and (d) young humans are more vocal while pointing than are chimpanzees.

“Reaching” as a Social Gesture

Pointing in humans has typically been defined as the extension of the index finger (only), with flexion of the remaining fingers into the (sometimes) pronated palm and concomitant extension of the arm (e.g., Butterworth & Grover, 1988; Franco & Butterworth, 1996; Leung & Rheingold, 1981; O’Neill, 1996). Arm or finger extensions that do not meet these four criteria in human studies (or three criteria in which palm orientation is not taken into consideration; e.g., Leung & Rheingold, 1981) are classified as either “reaches” or “indicative gestures” (Franco & Butterworth, 1996; O’Neill, 1996). In contrast to the relatively standard definition of the prototypical human point (or “canonical pointing”; Butterworth, 1998, p. 180), no clear consensus exists in the human developmental literature as to how one distinguishes a “reach” from an indicative gesture. Table 2 lists a representative sample of definitions of “reaching” by human infants and several definitions of gestures in studies that differentiate reaching from indicating. Comparison of these definitions renders the conclusion that, in studies of gesture use by human infants, reaching and indicating are not uniformly distinguished. For example, Blake, McConnell, Horton, and Benson (1992) defined a reach as “arm is extended, palm usually down, hand open and fingers straight” (p. 135), and O’Neill (1996) defined an indicate as a “whole hand point with all fingers extended” (p. 664).

Table 2.

Definitions of Reaching and Indicating in Human Infant Studies

| Gesture | Definition |

|---|---|

| Reach | “An arm extension towards a toy which gave the impression of being intentional [i.e., was accompanied by visual fixation of object]” (Murphy & Messer, 1977, p. 344) |

| Reach | “Extensions of the arm toward a stimulus object with a closed or open hand while looking at it” (Leung & Rheingold, 1981, p. 216) |

| Reach | “Extensions of the arm with hand open” (Masur, 1983, p. 97) |

| Reach | “Arm is extended, palm usually down, hand open and fingers straight.… This reach is for something out of reach” (Blake, McConnell, Horton, & Benson, 1992, p. 135) |

| Reach-out | “Arm extended, hand open, directed towards person or object” (Blake, O’Rourke, & Borzellino, 1994, p. 197) |

| Reaching | “Arm extended with palm held downward in a grasping posture” (Franco & Wishart, 1995, p. 166) |

| Reaching | “The arm is extended with the palm of the hand in a downward, open-handed reaching posture” (Franco & Butterworth, 1996, p. 314) |

| Reaching | “Arm extended with repetitive flexing of fingers” (D. K. O’Neill, personal communication, May 27, 1998) |

| Indicating | “Arm extended but with no conventional pointing posture of the hand—e.g., arm extended with little finger extended or with fingers clenched” (Franco & Wishart, 1995, p. 166) |

| Indicating | [=arm point] “The arm is extended towards the target while the hand assumes various postures (e.g., hand held with all fingers extended, or fingers tightly clenched)” (Franco & Butterworth, 1996, p. 314) |

| Indicates | “Whole hand point with all fingers extended” (O’Neill, 1996, p. 664) |

Pointing and putative “reaching” are quite similar in functional terms. For example, Leung and Rheingold (1981) reported that in their landmark study of 48 human infants from 10 to 17 months of age, “reaching” and pointing did not substantially differ in terms of the behavioral concomitants of these gestures: (a) visual monitoring by the infants of their mothers while pointing or reaching and (b) vocalizations while gesturing. In fact, vocalizations or looks to the mothers accompanied 86% and 94% of “reaches” and points, respectively. Leung and Rheingold described reaching as a “social gesture” (p. 218). Masur (1983) reported that in her longitudinal study of 4 infants from 8 to 18 months of age, the onset of concomitant gaze alternation (“dual-directional signaling”) was roughly simultaneous for the three categories of gestures, including pointing, showing objects, and “open-handed reaches.” Strikingly, in a study that included 12 human infants who were about 1 year old, Blake, O’Rourke, and Borzellino (1994) reported that “reach-out” gestures, which were defined as reaches toward out-of-reach items (see Table 2), were by far the most common gestures elicited to out-of-reach milk (87% of gestures) whereas only 3% of gestures in this context comprised points with the index finger. In that same study, approximately equal percentages of reach-outs (31%) and index-finger points (34%) were directed toward distant objects viewed from a window. Murphy and Messer (1977) observed that their infant subjects’ “behavior while using both types of gesture [reaches and canonical points] showed no apparent functional differences” (p. 347). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that a considerable proportion of arm and simultaneous multiple-finger extensions displayed by human infants are communicative in function. This important functional distinction is recognized by those researchers who distinguish “indicatives” as a class of communicative behavior (e.g., Franco & Butterworth, 1996; Franco & Wishart, 1995; O’Neill, 1996). For example, Franco and Butterworth (1996) remarked that “in the second year of life … reaching is accompanied by looks to the social partner … [and] both pointing and reaching have acquired the status of intentional gestures” (p. 311). Putative “reaches” in young humans, after about 1 year of age, do not appear to be actual attempts to grasp objects when those objects are clearly out of reach.

In summary, what have heretofore been widely termed reaches by human infants are frequently communicative gestures. We refer to these gestures as “whole-hand points” and consider them a subcategory of a general category of indicating behavior that we might term indicatives. In accordance with this terminology, pointing with the index finger is also a subcategory of indicative gestures. By describing the gestures in terms of both their structure and function, comparison across studies both within and between species will be facilitated. Although the term reach has a dual meaning, (a) to stretch out or extend and (b) to touch or grasp, its common use in the latter sense suggests that the term reach is more appropriately reserved for actual attempts at prehension.

The Structure of Pointing in Comparative Perspective

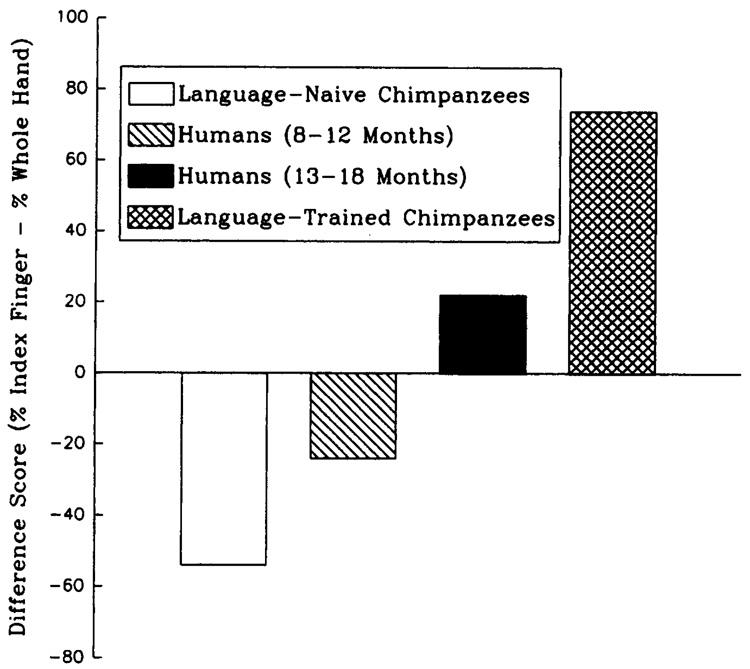

Figure 1 depicts the relative percentage of finger extensions involving the index finger, compared with the percentage of finger extensions involving the whole hand, in human infants and apes. Data from human studies were limited to those in which reaches or indicative gestures were defined in terms of extended fingers (rather than repetitive grasping motions or some other indicative gesture) and then were lumped across studies by age class. As can be seen in Figure 1, laboratory chimpanzees exhibit the least and the most reliance on index-finger extensions among the groups compared. Prima facie, there is an association of greater reliance on pointing with the index finger among those subjects (older human infants and language-trained chimpanzees) who have greater linguistic competence. However, these groups also have more experience in face-to-face interactions with adult humans, irrespective of their linguistic competence. Language-trained apes experience a multitude of relatively unique rearing circumstances, compared with other laboratory-reared apes, and it remains ambiguous whether language training, per se, or some correlate of language training may account for the differences in the preferred form of pointing seen between the two chimpanzee samples depicted in Figure 1. This pattern of data does serve to refute a widespread belief that humans point relatively more often with the index finger than do nonhumans in experimental contexts. Clearly, it depends on the particular group of chimpanzees studied. The factor of species alone cannot account for the number of fingers extended in experimental contexts.

Figure 1.

Ratio of index-finger to whole-hand extensions to objects distal to both interactants in apes and humans, irrespective of whether the objects were food or toys, expressed as a difference score. Negative numbers reflect a majority of whole-hand extensions, whereas positive numbers reflect a preponderance of index-finger extensions. Data sources: language-naive chimpanzees: Leavens et al. (1996) and a reanalysis of data reported by Leavens and Hopkins (1998; index-finger points and whole-hand points); humans (8–12 months): Blake et al. (1994; prepoints, reaches, and points for the conditions; object out of reach and point to object included; all other gestures and conditions excluded), Franco and Butterworth (1996; points and reaches), and Masur (1983; points and reaches); humans (13–18 months): Franco and Butterworth (1996; points and reaches) and Masur (1983; points and reaches); and language-trained chimpanzees: Krause and Fouts (1997, Experiments 1 and 2 combined; index-finger points and whole-hand points).

Because so many of the chimpanzee pointing gestures reported by Krause and Fouts (1997) were with the index finger, it is no longer tenable to suggest that morphological considerations play a central role in the number of fingers extended during pointing by apes. The claim by Povinelli and Davis (1994) that chimpanzees do not point with the index finger and that this may be attributable to morphological differences in the hands of chimpanzees and humans is not consistent with the data summarized in Figure 1. This is not to suggest that there are no meaningful morphological differences in pointing between apes and humans. Chimpanzee and human hands, for example, differ strikingly in many features (the phalanges are more curved in chimpanzees, the thumbs are positioned more proximally in chimpanzees, etc.). However, chimpanzees do frequently point with their index fingers, and any putative species difference in the number of fingers extended while pointing is not evident in Figure 1. This suggests that pointing with the index finger is related to as yet unknown variables in the rearing histories of chimpanzees.

Several studies have noted that the proportion of gestures that are canonical points tends to increase whereas the proportion of reaches or indicatives tends to remain relatively constant in human samples from younger than 1 year of age to approximately 2 years of age (Franco & Butterworth, 1996; Leung & Rheingold, 1981; Locke, Young, Service, & Chandler, 1990). This difference in developmental patterns implies a different functional basis for the two gestures in young humans. In the human populations studied, it may be the case that pointing with the whole hand is associated with requestive functions and that canonical pointing becomes preferentially associated with paralinguistic functions (cf. Franco & Butterworth, 1996).

Audience Effects on Pointing

To unambiguously demonstrate the communicative function of putative “reaches” in humans, it would be necessary simply to compare the frequency of “reaches” to desirable but obviously out-of-reach objects in the presence versus the absence of a communicative interactant. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of such studies of audience effects on whole-hand points in humans. Franco and Butterworth (1990, as cited in Butterworth, 1998) reported that the production of canonical pointing in their sample of human infants was dependent on the presence of an observer. Similar studies could be performed that include noncanonical points (e.g., whole-hand points) in the scoring procedure.

An alternative design would manipulate the attentional status of the caregiver or interactant and measure the frequency and type of gesture emitted in different attentional contexts. Bakeman and Adamson (1986) reported that, beginning at approximately 12 months of age in infants, mothers’ attention facilitated the relative incidence of canonical pointing in their infants, compared with a condition in which the mothers were inattentive to the infants. More recently, O’Neill (1996) reported that 2-year-olds exhibited more canonical pointing and other indicative gesturing (including pointing with the whole hand) when their parents were ignorant of (had not seen) the hidden location of target items, compared with when these same parents were knowledgeable about (had seen) the location of these target items. If human infants exhibit the same magnitude of audience effects while gesturing with both index-finger and whole-hand points, then the communicative function of the latter would be demonstrated.

There are three extant studies of audience effects on pointing (with the index finger and with all fingers extended) by apes. Call and Tomasello (1994) reported that 2 orangutans pointed less often when the experimenter was facing away or absent than when the experimenter was facing them. In their study, 1 of the orangutans pointed primarily with his index finger, whereas the other pointed primarily with her whole hand. Leavens et al. (1996) reported that 99% of the index-finger and whole-hand points emitted by 3 chimpanzees occurred in the presence of a human observer. Krause and Fouts (1997) reported that 99% of the points emitted by their 2 chimpanzee subjects were emitted only after the experimenter had turned to face them. As noted above, these 2 chimpanzees pointed primarily with their index fingers. Thus, the presence or attentional status of the observer exerted a controlling influence on the pointing of these 7 ape subjects. Therefore, the data for apes and human infants are very similar with respect to the facilitative effects of audience factors on pointing behavior.

Similar audience effects also have been well established for a suite of gestures, other than pointing, exhibited by chimpanzees. Tomasello, Call, Nagell, Olguin, and Carpenter (1994) reported that no purely visual signals were emitted by 8 chimpanzees to individuals who were not attending to (i.e., looking at) the signaler. Therefore, sensitivity to the attentional status of an observer is a common element in the use of gestures by chimpanzees.

A different kind of audience effect was reported by Woodruff and Premack (1979). They found that 2 of their 4 chimpanzee subjects eventually refrained from indicating (with a variety of behaviors, including pointing) a baited container in the presence of a “competitive” experimenter, who reliably failed to deliver the indicated food. The 2 remaining chimpanzees came to reliably indicate the unbaited container in the presence of the competitive experimenter (i.e., came to exhibit deceptive pointing). Similar audience effects were found in a systematic replication of Woodruff and Premack’s study using capuchin monkeys as subjects (Mitchell & Anderson, 1997). In this replication, 2 capuchins refrained from indicating a baited container, and 1 capuchin eventually pointed deceptively (i.e., to the unbaited container) in the presence of a competitive experimenter. As reviewed by Mitchell and Anderson, deceptive pointing in human children is not common before 4 years of age.

Audience effects on index-finger and whole-hand pointing by monkeys and apes, then, are experimentally well established. As noted by Bates et al. (1975) and many subsequent researchers, canonical pointing by humans first develops without reference to the attentional status of an observer and later becomes integrated into a pattern of behavior that is characterized by visual monitoring of other social agents (especially primary caretakers) in the immediate environment. That is, pointing in human infants is at first not subject to audience effects and then gradually becomes under the control of factors related to visual attention in their caretakers and other individuals in their environments. The developmental course of this sensitivity to audience factors in apes and monkeys has received very little study (but see Miles, 1990).

Pointing as a Social Gesture

At approximately 1 year of age, pointing is exhibited by more than half of the human infants in most studies of pointing, and the relative incidence of pointing in such studies is an increasing function from 8 to about 18 months of age, with striking agreement across studies (Figure 2A; Blake et al., 1994; Franco & Butterworth, 1996; Lempers, 1979; Leung & Rheingold, 1981). Typically, after a period of time in which finger and arm extensions are directed toward objects in a noncommunicative fashion (i.e., without concomitant gaze orientation toward social agents, such as caregivers), pointing begins to be integrated into a pattern of behavior in which successive visual orienting is exhibited toward social agents and the object of the point (Figure 2B). This visual-orienting behavior is generally characterized in two ways: (a) as looks to the caregiver (“visual monitoring”; Leung & Rheingold, 1981; “visual checking”; e.g., Franco & Butterworth, 1996) and (b) as successive looks between an object or event and a social agent (“gaze alternation”; e.g., Bates, O’Connell, & Shore, 1987; “dual-directional signaling”; Masur, 1983; “social referencing”; e.g., Dickstein & Parke, 1988). As is evident in Figure 2B, the majority of infants studied exhibit some form of visual monitoring of adults with their pointing near the beginning of their 2nd year of life.

Figure 2.

The development of pointing in humans. The proportions of infants who pointed in several large-scale studies are depicted. Open symbols denote pointing without regard to the visual attention of caretakers, whereas filled symbols denote pointing with concomitant visual orienting to caretakers. The width of the open rectangles marks the youngest and oldest samples in which at least 50% of the participants exhibited pointing (A) or communicative pointing (B). The study by Desrochers et al. (1995) was quasi-longitudinal, whereas the remaining studies were cross-sectional.

One also can ask what proportion of gestures are accompanied by gaze alternation in human and nonhuman samples. In a longitudinal study by Masur (1983), gaze alternation accompanied none of the pointing gestures emitted by the 4 infants between 8 and 12 months of age, and gaze alternation accompanied 33% of the points these same 4 infants exhibited from 13 to 18 months of age. Leung and Rheingold (1981) reported that visual monitoring of the mothers was exhibited during 38% of the points (and 45% of the reaches) emitted by their 48 young infants from 9 to 17 months of age. Franco and Butterworth (1996) reported that their 8 youngest infants (12 months old) exhibited visual checking during 47% of their pointing gestures (and 31% of their reaching gestures).

In contrast, laboratory chimpanzees exhibit relatively high rates of gaze alternation between experimenters and food while pointing toward the food. Leavens et al. (1996) reported that a 14-year-old chimpanzee named Clint exhibited gaze alternation during 76% of his pointing gestures. Krause and Fouts (1997) reported that their 2 adult chimpanzee subjects exhibited gaze alternation while pointing during 97 of 100 experimental trials. Data reported by Leavens and Hopkins (1998) were reanalyzed in terms of gestures (rather than gesturing individuals, as originally reported): 90% of the points exhibited by their subjects (from 3 to 56 years of age) were accompanied by gaze alternation. A cebus monkey studied by Mitchell and Anderson (1997) exhibited a high rate of looking at the experimenter while pointing to a baited container (68% of trials). A recent report of pointing in a wild bonobo also described gaze alternation between human observers and other bonobos by an individual who was pointing at the human observers (Veà & Sabater-Pi, 1998).

Clearly, captive apes in several gestural studies exhibited higher levels of gaze alternation between distal food objects and human interactants than did several samples of relatively young human infants between distal, usually nonfood, items and human interactants. This pattern of visual-orienting behavior while gesturing is cardinally definitive of intentional communication in humans (Bates et al., 1975; Terrace, 1985; Tomasello, 1995). The comparison across taxa suggests that these visual-orienting behaviors are common attributes of nonverbal referential communication in humans, apes, and perhaps monkeys as well.

Pointing as a Paralinguistic Gesture in Humans

Human infants appear to be more vocal while pointing than are captive apes. Across human studies (i.e., treating each report as an independent data point), the mean percentage of gestures accompanied by vocalizations is 82% (Dobrich & Scarborough, 1984: 77%; Franco & Butterworth, 1996: 76%; Leung & Rheingold, 1981: 88%; Masur, 1983: 82%; Zinober & Martlew, 1985: 85%). In contrast, the mean percentage of gestures accompanied by vocalizations in two studies of chimpanzees was 31% (Leavens & Hopkins, 1998: 38%; Leavens et al., 1996: 24%). Two of the human infant studies, however, reported the percentage of vocalizations that were recognizably linguistic. Calculations based on their published data revealed that Masur (1983) and Zinober and Martlew (1985) found that 59% (age range: 8–18 months) and 41% (age range 10–21 months), respectively, of the deictic (referential) gestures they studied were accompanied by vocalizations that could not be confidently identified as linguistic. Hence, a considerable portion (approximately 50%) of human infant pointing is accompanied by linguistically ambiguous vocalizations from approximately 8 to 21 months of age.

As noted by Butterworth (1998), pointing frequently accompanies naming behavior in humans, especially human infants and their primary caretakers. This behavior has no obvious corollary in the communication of non-language-trained apes. Hence, pointing by humans serves both requestive and declarative functions (Bates et al., 1975) but seems to be restricted to requestive domains for language-naive apes (e.g., Butterworth, 1998; Gómez, Sarriá, & Tamarit, 1993).

Pointing by language-trained apes does, apparently, sometimes serve declarative functions. For example, Chantek, a sign-language-trained orangutan, was reported to point in both instrumental and declarative contexts; he pointed “to bring his caregiver’s attention to [an] object or simply to acknowledge its presence” (Miles, 1990, p. 525). Another example is that of private signing by sign-language-trained chimpanzees, who point to pictures in books and name the depicted objects (Krause, 1997). Pointing by apes, then, can expand beyond requestive contexts, given unusual training histories, especially language training (cf. Terrace, 1985). Language-trained apes do appear to use pointing as a paralinguistic gesture to disambiguate the targets of particular signed communicative acts (e.g., Krause & Fouts, 1997; Miles, 1990; Patterson, 1978). However, this paralinguistic use of pointing does not entail increased vocal output, presumably because language-trained apes typically learn sign languages or other visually based languages, such as Yerkish (Rumbaugh, 1976).

In summary, pointing, particularly with the index finger, is a stereotyped, species-typical gesture in humans; apes, however, commonly adopt pointing behavior when they are raised in captivity. A considerable, but unspecified, portion of human infants’ gestural behavior that is commonly referred to as reaching is communicative in function and should not be confused with direct attempts to grasp unattainable objects. Pointing by apes and some monkeys, like pointing by humans, is accompanied by visual monitoring of a communicative interactant, or gaze alternation between these communicative interactants and the referents of the points. Apes are less vocal while pointing than are human infants, even when specifically linguistic human vocalizations are taken into account.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants RR-00165 and NS-29574 and a University-Wide Graduate School Assistantship from the University of Georgia. The Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center is fully accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

We thank Kim A. Bard, Sarah T. Boysen, George Butterworth, Josep Call, Juan-Carlos Gómez, Mark A. Krause, H. Lyn Miles, and Daniella K. O’Neill for numerous insightful discussions of pointing.

Contributor Information

David A. Leavens, Department of Psychology, University of Georgia and Living Links Center, Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center, Emory University

William D. Hopkins, Department of Psychology, Berry College and Living Links Center, Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center, Emory University.

References

- Adamson LB, Bakeman R. The development of shared attention during infancy. Annals of Child Development. 1991;8:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Adamson LB. Infants’ conventionalized acts: Gestures and words with mothers and peers. Infant Behavior and Development. 1986;9:215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Bard KA. Intentional behavior and intentional communication in young free-ranging orangutans. Child Development. 1992;62:1186–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates E, Camaioni L, Volterra V. Performatives prior to speech. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1975;21:205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Bates E, O’Connell B, Shore C. Language and communication in infancy. In: Osofsky JD, editor. Handbook of infant development. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 1987. pp. 149–203. [Google Scholar]

- Blake J, McConnell S, Horton G, Benson N. The gestural repertoire and its evolution over the second year. Early Development and Parenting. 1992;1:127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Blake J, O’Rourke P, Borzellino G. Form and function in the development of pointing and reaching gestures. Infant Behavior and Development. 1994;17:195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Blaschke M, Ettlinger G. Pointing as an act of social communication in monkeys. Animal Behaviour. 1987;35:1520–1523. [Google Scholar]

- Boysen ST, Berntson GG. Numerical competence in a chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1989;103:23–31. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.103.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth G. What is special about pointing? In: Simion F, Butterworth G, editors. The development of sensory, motor, and cognitive capacities in early infancy: From perception to cognition. Hove, England: Psychology Press/Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth G, Grover L. The origins of referential communication in human infancy. In: Weiskrantz L, editor. Thought without language. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1988. pp. 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Call J, Tomasello M. Production and comprehension of referential pointing by orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1994;108:307–317. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.108.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole RF., Jr . The ontogeny of pointing in young children. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 1974. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Desrochers S, Morissette P, Ricard M. Two perspectives on pointing in infancy. In: Moore C, Dunham PJ, editors. Joint attention: Its origins and role in development. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1995. pp. 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- de Waal FBM. Chimpanzee politics: Power and sex among apes. New York: Harper & Row; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein S, Parke RD. Social referencing in infancy: A glance at fathers and marriage. Child Development. 1988;59:506–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb01484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrich W, Scarborough HS. Form and function in early communication: Language and pointing gestures. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1984;38:475–490. doi: 10.1016/0022-0965(84)90090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald M. Origins of the modern mind: Three stages in the evolution of culture and cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fouts RS, Hirsch AD, Fouts DH. Cultural transmission of a human language in a chimpanzee mother–infant relationship. In: Fitzgerald HE, Mullins JA, Gage P, editors. Child nurturance: Studies of development in primates. New York: Plenum Press; 1982. pp. 159–193. [Google Scholar]

- Franco F, Butterworth G. Pointing and social awareness: Declaring and requesting in the second year. Journal of Child Language. 1996;23:307–336. doi: 10.1017/s0305000900008813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco F, Wishart JG. Use of pointing and other gestures by young children with Down syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1995;100:160–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness WH. Observations on the mentality of chimpanzees and orangutans; Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society; 1916. pp. 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner BT, Gardner RA. Two-way communication with an infant chimpanzee. In: Schrier AM, Stollnitz F, editors. Behavior of nonhuman primates: Modern research trends. Vol. 4. New York: Academic Press; 1971. pp. 117–183. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez JC, Sarriá E, Tamarit J. The comparative study of early communication and theories of mind: Ontogeny, phylogeny, and pathology. In: Baron-Cohen S, Tager-Flusberg H, Cohen D, editors. Understanding other minds: Perspectives from autism. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 397–426. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez JC, Teixidor P. Theory of mind in an orangutan; Paper presented at the 14th Congress of the International Primatological Society; Strasbourg, France. 1992. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Hayes KJ, Hayes C. The cultural capacity of chimpanzee. Human Biology. 1954;26:288–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess J, Novak MA, Povinelli DJ. “Natural pointing” in a rhesus monkey, but no evidence of empathy. Animal Behaviour. 1993;46:1023–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Horne PJ, Lowe CF. On the origins of naming and other symbolic behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1996;65:185–241. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1996.65-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg WN, Kellogg LA. The ape and the child: A study of early environmental influence upon early behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Krause MA. Comparative perspectives on pointing and joint attention in children and apes. International Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1997;10:137–157. [Google Scholar]

- Krause MA, Fouts RS. Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) pointing: Hand shapes, accuracy, and the role of eye gaze. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1997;111:330–336. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.111.4.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavens DA, Hopkins WD. Intentional communication by chimpanzees: A cross-sectional study of the use of referential gestures. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:813–822. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavens DA, Hopkins WD, Bard KA. Indexical and referential pointing in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1996;110:346–353. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.110.4.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lempers JD. Young children’s production and comprehension of nonverbal deictic behaviors. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1979;135:93–102. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1979.10533420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lempers JD, Flavell ER, Flavell JH. The development in very young children of tacit knowledge concerning visual perception. Genetic Psychology Monographs. 1977;95:3–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung EHL, Rheingold HL. Development of pointing as a social gesture. Developmental Psychology. 1981;17:215–220. [Google Scholar]

- Locke A, Young A, Service V, Chandler P. Some observations on the origins of the pointing gesture. In: Volterra V, Erting CJ, editors. From gesture to language in hearing and deaf children. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1990. pp. 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Masur EF. Gestural development, dual-directional signaling, and the transition to words. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 1983;12:93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Miles HL. The cognitive foundations for reference in a signing orangutan. In: Parker ST, Gibson KR, editors. “Language” and intelligence in monkeys and apes: Comparative developmental perspectives. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 511–539. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RW, Anderson JR. Pointing, withholding information, and deception in capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1997;111:351–361. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.111.4.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, Messer DJ. Mothers, infants and pointing: A study of a gesture. In: Schaffer HR, editor. Studies in mother–infant interaction. London: Academic Press; 1977. pp. 325–354. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill DK. Two-year-old children’s sensitivity to a parent’s knowledge state when making requests. Child Development. 1996;67:659–677. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson FG. Linguistic capabilities of a lowland gorilla. In: Peng FCC, editor. Sign language and language acquisition in man and ape: New dimensions in comparative pedolinguistics. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1978. pp. 161–201. [Google Scholar]

- Petitto L. “Language” in the prelinguistic child. In: Kessel F, editor. Development of language and language researchers. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 187–222. [Google Scholar]

- Povinelli DJ, Davis DR. Differences between chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and humans (Homo sapiens) in the resting state of the index finger: Implications for pointing. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1994;108:134–139. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.108.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povinelli DJ, Nelson KE, Boysen ST. Inferences about guessing and knowing by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1990;104:203–210. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.104.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povinelli DJ, Parks KA, Novak MA. Role reversal by rhesus monkeys, but no evidence of empathy. Animal Behaviour. 1992;43:269–281. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaugh DM. Language learning by a chimpanzee: The Lana Project. New York: Academic Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Savage-Rumbaugh ES. Pan paniscus and Pan troglodytes: Contrast in preverbal communicative competence. In: Susman RL, editor. The pygmy chimpanzee: Evolutionary biology and behavior. New York: Plenum Press; 1984. pp. 395–413. [Google Scholar]

- Savage-Rumbaugh ES. Ape language: From conditioned response to symbol. New York: Columbia University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Savage-Rumbaugh ES, Wilkerson BJ, Bakeman R. Spontaneous gestural communication among conspecifics in the pygmy chimpanzee (Pan paniscus) In: Bourne GH, editor. Progress in ape research. New York: Academic Press; 1977. pp. 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg A, Fujita K. Pointing at smaller food amounts in an analogue of Boysen and Berntson’s (1995) procedure. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1996;66:143–147. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1996.66-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman S. The development of preverbal communication: Its contributions and limits in promoting the development of language. In: Schiefelbusch RL, Pickar J, editors. The acquisition of communicative competence. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1984. pp. 23–67. [Google Scholar]

- Terrace HS. Nim. New York: Washington Square Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Terrace HS. In the beginning was the “name.”. American Psychologist. 1985;40:1011–1024. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.40.9.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M. Joint attention as social cognition. In: Moore C, Dunham PJ, editors. Joint attention: Its origins and role in development. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1995. pp. 103–130. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M, Call J, Nagell K, Olguin R, Carpenter M. The learning and use of gestural signals by young chimpanzees: A trans-generational study. Primates. 1994;35:137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M, George BL, Kruger AC, Farrar MJ, Evans A. The development of gestural communication in young chimpanzees. Journal of Human Evolution. 1985;14:175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Veà JJ, Sabater-Pi J. Spontaneous pointing behaviour in the wild pygmy chimpanzee (Pan paniscus) Folia Primatologica. 1998;69:289–290. doi: 10.1159/000021640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner H, Kaplan B. Symbol formation: An organismic-developmental approach to language and the expression of thought. New York: Wiley; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Whiten A. Chimpanzee cognition and the question of meta-representation. In: Sperber D, editor. [a book on metarepresentation] Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff G, Premack D. Intentional communication in the chimpanzee: The development of deception. Cognition. 1979;7:333–362. [Google Scholar]

- Zinober B, Martlew M. Developmental changes in four types of gesture in relation to acts and vocalizations from 10 to 21 months. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1985;3:293–306. [Google Scholar]