Abstract

Coenzyme Q (Q) is a redox active lipid that is an essential component of the electron transport chain. Here, we show that steady state levels of Coq3, Coq4, Coq6, Coq7 and Coq9 polypeptides in yeast mitochondria are dependent on the expression of each of the other COQ genes. Submitochondrial localization studies indicate Coq9p is a peripheral membrane protein on the matrix side of the mitochondrial inner membrane. To investigate whether Coq9p is a component of a complex of Q-biosynthetic proteins, the native molecular mass of Coq9p was determined by Blue Native-PAGE. Coq9p was found to co-migrate with Coq3p and Coq4p at a molecular mass of approximately 1 MDa. A direct physical interaction was shown by the immunoprecipitation of HA-tagged Coq9 polypeptide with Coq4p, Coq5p, Coq6p and Coq7p. These findings, together with other work identifying Coq3p and Coq4p interactions, identify at least six Coq polypeptides in a multi-subunit Q biosynthetic complex.

INTRODUCTION

Coenzyme Q (or Q)1 is a key component of the electron transport chain. In mitochondria, Q carries electrons from Complexes I and II to Complex III. Nine genes, designated COQ1 through COQ9, have been identified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae as necessary for Q biosynthesis [1, 2]. Enzymatic functions for most of these gene products have been identified. Coq1p synthesizes the polyisoprenyl tail [3], Coq2p transfers it to 4-hydroxybenzoic acid [4]. Coq3p, Coq5p, Coq6p and Coq7p are responsible for a series of modifications to the benzoquinone ring to form Q [5-8]. The functional roles of Coq4p, Coq8p and Coq9p in Q biosynthesis are unknown. COQ8 was originally identified as ABC1 and thought to function as a chaperone for the bc1 complex but this has since been shown to be incorrect and that its only discernable role is in Q biosynthesis [9, 10].

Genetic studies have shown interdependence between the Q biosynthetic proteins, suggesting they exist in a multi-subunit complex in S. cerevisiae. Escherichia coli strains harboring mutations in the Q biosynthetic ubi genes tend to accumulate the biosynthetic intermediate preceding the blocked step [11]. In contrast, yeast strains with mutations in any gene from coq3 - coq9 accumulate an early intermediate of Q, 3-hexaprenyl-4-hydroxybenzoic acid (HHB) [1, 12]. Studies with these yeast mutants have shown that polypeptide levels of Coq3p, Coq4p and Coq6p are decreased when there is a mutation in any coq gene [13-15]. Recent studies have presented physical evidence that several of the Coq proteins associate in a large protein complex [16]. Size exclusion chromatography, Blue Native gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE), and co-precipitation of Coq4p with biotin-tagged Coq3p have indicated that Coq3p and Coq4p interact and are present in a protein complex of greater than 1,000 kDa. Coq7p also co-migrates with the Coq3p/Coq4p large molecular mass complex [17].

A newly identified gene, COQ9, has been shown to be necessary for Q biosynthesis [1]. The amino acid sequence of Coq9p defines a distinct, uncharacterized, conserved, single domain protein family (COG5590) [18]. High scoring homologs of Coq9 are readily identified in each of the represented eukaryotic genomes, and significant homologs are also present in some members of the alpha-proteobacteria. Coq9p has no clear homology to any proteins of known function and the role it plays in Q biosynthesis is unknown. ABC1/COQ8 was identified as a multicopy suppressor of a specific coq9 mutation, coq9-1 [1]. Leonard et al. [19] identified kinase sequence motifs in Abc1/Coq8p, and suggested that it may function as a protein kinase. The suppression of the coq9-1 mutation by multicopy ABC1/COQ8 suggests that Coq9p may interact with Abc1/Coq8p, perhaps as a substrate of Abc1/Coq8p. In this study we investigate the mechanism of this suppression and characterize the interactions of Coq9p with other yeast Coq proteins. While no interaction was detected between the HA-tagged form of Coq9 and Abc1/Coq8p, we find that Coq4p, Coq5p, Coq6p and Coq7p co-precipitate with the Coq9-HA polypeptide.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast Strains and Media

Yeast strain genotypes and sources are listed in Table 1. Media were prepared as described [20], and included YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% yeast peptone, 2% dextrose) and YPGal + 0.1% Dex (1% yeast extract, 2% yeast peptone, 2% galactose, 0.1% dextrose). 2% bacto agar was added for solid media. Media components were obtained from Difco, Fisher, and Sigma.

Table 1.

Genotype and Source of Yeast Strains

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| W303-1A | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 | R. Rothsteina |

| W303ΔCOQ9 | MAT α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq9::URA3 | [1] |

| W303ΔCOQ9/ST8 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq9::URA3 leu2::COQ9HA-LEU2 | [1] |

| C92/UL3 | MAT a leu2-3,122 ura3-1 coq9-1 | [1] |

| W303ΔCOQ1 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq1::LEU2 | [13] |

| W303ΔCOQ2 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq2::HIS3 | [4] |

| CC303 | MAT α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq3::LEU2 | [39] |

| W303ΔCOQ4 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq4::TRP1 | [15] |

| W303ΔCOQ5 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq5::HIS3 | [5] |

| W303ΔCOQ6 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq6::LEU2 | [6] |

| W303ΔCOQ7 | MAT α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq7::LEU2 | [40] |

| W303ΔABC1 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 abc1/coq8::HIS3 | [15] |

| W303ΔCOQ10 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq10::HIS3 | [31] |

| W303ΔATP2 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 atp2::LEU2 | [39] |

| CC304.1 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 cor1::HIS3 | [41] |

| JM43 | MAT α his4-580 leu2-3 leu2-112 trp1-289 ura3-52 | [42] |

Dr. Rodney Rothstein, Department of Human Genetics, Columbia University.

Sequencing of the coq9-1 Allele

A 5 ml YPD culture of the yeast strain C92/UL3 was grown overnight at 30°C. Genomic DNA was isolated with the Wizard Genomic DNA Kit (Promega). The COQ9 allele was amplified with the primers pCOQ9flankF (5′ CCCCACCCCCTTCGTAATGG 3′, -243 to -234 relative to the ATG of the COQ9 ORF) and pCOQ9flankR (5′ CATAAGGGACAAGCAGG 3′, +1028 to +1012). The amplified DNA was purified with the Qiagen Gel Extraction Kit. DNA sequencing was performed by the UCLA Sequencing and Genotyping Core.

Preparation of Whole Cell Lysates

Yeast whole cell lysates for analysis by SDS-PAGE were prepared as described [21].

Mitochondria Purification and Solubilization

Yeast cells were grown in YPGal + 0.1% Dex. Mitochondria were isolated and purified on nycodenz gradients as described [22]. Protein concentrations were determined by bicinchoninic protein assay (Pierce). For solubilization, mitochondria were sedimented by centrifugation (14,000 × g, 5 min) and resuspended to 10 μg/ul in solubilization buffer (2:1 digitonin:protein ratio, 50 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.4 mM Pefabloc SC (Sigma-Aldrich)). Mitochondria were incubated for 45 min at 4°C with periodic gentle mixing. Soluble supernatant and insoluble pellet materials were separated by high-speed centrifugation in an A-100/18 rotor pre-chilled at - 20°C (Beckman Airfuge, 100,000 × g, 20 min).

Sub-mitochondrial Localization of Coq9p

Mitochondria of wild-type yeast (JM43) grown in YPGal + 0.1% Dex were isolated and purified as described above. Sub-fractionation of purified mitochondria was performed by generating mitoplasts as described [23]. Mitochondria (3 mg protein) were suspended in five volumes of 20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4, and incubated on ice for 30 min. The mixture was then centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to separate the intermembrane space components (supernatant) from the mitoplasts (pellet).

The mitoplasts were sonicated (four 20-second pulses on ice slurry, 20% duty cycle, 2.5 output setting; Sonifier W350, Branson Sonic Power Co.), and then sedimented by centrifugation (100,000 × g, one hr at 4°C) to generate matrix (supernatant) and membrane (pellet) fractions. Alternatively, the mitoplasts were subjected to alkaline carbonate extraction [24] and the mixture was subjected to centrifugation as before to separate the peripheral membrane and matrix components (supernatant) from the integral membrane components (pellet). Equal aliquots of starting mitochondria, untreated mitoplasts, intermembrane space components and the pellet and supernatant fractions from either sonication or alkaline carbonate extraction were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis followed by immunoblot.

Proteinase K protection experiments were carried out as described in [25] with some modifications. Proteinase K was added from a freshly made concentrated stock solution (10 mg/ml) to mitochondria re-suspended in buffer C (0.6 M Sorbitol, 20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4; 0.3 mg protein/ml) to a final concentration of 100 μg protease/ml. For treatment of mitoplasts, the protease was present in the hypo-osmotic buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH7.4). When required, Triton X-100 and SDS were added to final concentrations of 1% and 0.5% (w/v), respectively. The protease-treated samples were incubated for 30 min at 4°C. To inactivate the Proteinase K, PMSF was added and the samples were treated with trichloroacetic acid (20% final concentration) at 60°C. The samples were subjected to centrifugation and the pellets resuspended in Thorner buffer [26]; equal aliquots were processed for electrophoresis as described above.

Gel Electrophoresis

SDS-polyacrylamide denaturing gels were prepared containing 13% acrylamide as described [27]. For BN-PAGE, nycodenz purified mitochondria (200 μg protein) were solubilized as described above. Blue Native gels containing 5 - 13.5% acrylamide in a linear gradient were prepared and subjected to electrophoresis as described [16, 28].

Immunoprecipitation of Coq9p-HA

Mitochondria (250 μg) were pelleted by centrifugation (14,000 × g, 5 min) and resuspended in 125 μl IP buffer (140.7 mM NaCl, 9.3 mM Na2HPO4 pH 7.4, 1X Complete protease inhibitor (EDTA-free, Roche), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 4 mg/ml digitonin). The sample was incubated on ice for 30 min and insoluble components were sedimented by high-speed centrifugation (100,000 × g, 20 min). A biotinylated monoclonal antibody recognizing the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope (500 ng, Roche, Clone 3F10, Catalog number 12158167001) was added to the soluble supernatant, and the sample was incubated on a rotating shaker overnight at 4°C. CaptAvidin agarose beads (200 μl of 50% slurry, Molecular Probes) were added and the sample was incubated 2 hr at 4°C. Control samples were similarly prepared with wild-type mitochondria and antisera, and also with mitochondria expressing the tagged protein but without antibody. The CaptAvidin agarose beads were washed twice with 200 μl of wash buffer (140.7 mM NaCl, 9.3 mM Na2HPO4 pH 7.4, 2 mg/ml digitonin, 1X Complete protease inhibitor (EDTA-free, Roche Diagnostics)). The beads were mixed with 100 μl of 0.2 M glycine, pH 3 to elute bound material, and then treated with hot SDS-PAGE sample buffer (2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 62.5 mM Tris-Cl pH 6.8, 100 mM DTT, 0.5 mg bromophenol blue; one min) in order to strip them of remaining material.

Generation of Antibodies

Polyclonal antisera were obtained from rabbits by a standard immunization protocol (Cocalico Biologicals, Inc., Reamstown, PA) and when necessary, the antisera was affinity purified as described [29]. The specificity of the antisera was determined by immunoblotting with purified mitochondria from W303-1A and the corresponding coq null yeast strains. Based on the mobility in the SDS-PAGE, the apparent molecular weight of the mature Coq2, Abc1/Coq8, and Coq9 polypeptides are about 30, 53, and 25 kDa respectively.

To generate antibodies against Coq2p, a 0.34kb DNA fragment consisting of the 5′ end of the COQ2 locus was amplified from the genomic DNA with the primers N-NdeI-Coq2 (5′ GGAATTCCATATGATGTTTATTTGGCAGAGAAAGAG 3′) and C-115-Coq2 (5′ GCGGATCCTCAAGCACCTTGCATCATGGC 3′). The N-NdeI-Coq2 primer contained an NdeI restriction site (underline) and +1 to +23 of the COQ2 ORF; the C-115-Coq2 primer contained a BamHI restriction site (double underline) and +328 to +345 of the COQ2 ORF. The amplified DNA product was digested with NdeI and BamHI, and was then ligated to the NdeI and BamHI cut expression vector pET-15b (Novagen) to generate pETCOQ2-115. The pETCOQ2-115 plasmid expressing the C-terminal truncated form of Coq2 polypeptide with a six-Histidine tag at the N-terminus was used to transform E. coli strain Rosetta™2 (DE3) pLysS (Novagen). The fusion protein was induced by 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (Fisher Biotech) at 30°C for 4 hr, and purified from the bacterial lysate under denaturing conditions (6 M Guanidine-HCl, pH 7.4) by Ni-NTA Superflow resin (Qiagen). A small aliquot of the purified 15-kDa His-Coq2-115 fusion protein was visualized by Coomassie staining.

In order to remove Guanidine-HCl, the purified protein was transferred into Slide-A-Lyzer Dialysis Cassette (PIERCE) after hydration of the membrane. The cassette was immersed in 2L of 1x PBS with 2% glycerol and 2 M urea (pH 7.4) and was incubated for 6 hr. After the dialysis step was performed 2 times, the purified protein was concentrated by Amicon Ultra-10,000 MWCO (MILLIPORE).

To generate antibodies against Abc1/Coq8p, a 1.5 kb segment of DNA containing the ORF of ABC1/COQ8 was amplified by PCR with the primers pPG8F (5′ CCGCTCGAGATGGTTACAAATATGGTGAAATTG 3′, +1 to +24 corresponding to the ABC1/COQ8 ATG) and pPG8R (5′ CCGCTCGAGTTAAACTTTATAGGCAAAAATCTC 3′, +1506 to +1483). The amplified DNA was digested with XhoI (underlined) and ligated into the XhoI site of the vector pET-15b (Novagen). The resulting plasmid, pETQ8, contained ABC1/COQ8 with a 6-His tag at its N-terminus. The fusion protein was over-expressed in the E. coli strain BL21(DE3)-RIL (Stratagene) and purified under denaturing conditions over metalchelating affinity beads charged with NiSO4 (Chelating Sepharose Fast Flow, GE Healthcare). The purified protein was subject to dialysis (5 mM Guanidine-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, pH 8.6, 40% glycerol) and the band corresponding to His-Abc1/Coq8p was eluted from a preparative SDS-PAGE gel [30] with 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% SDS.

To generate antibodies against Coq9p, a 0.78 kb fragment of DNA containing COQ9 was amplified by PCR with the primers N-NdeI-Coq9 (5′ GGAATTCCATATGATGCTTTGTCGCAATACTGCC 3′, +1 to +21 corresponding to the COQ9 ATG) and C-BamHI-Coq9 (5′ CGGGATCCTTAACCCCTAACTAATTGAG 3′, +783 to +764). The amplified DNA was digested with NdeI (underlined) and BamHI (double underlined). The digested DNA fragment was ligated into the NdeI and BamHI sites of the expression vector pET-15b. The resulting plasmid, pETCOQ9, expressed Coq9p with a 6-His tag at its N-terminus. The fusion protein was over-expressed in the E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Stratagene) and purified over Ni-NTA Superflow resin (Qiagen).

Immunoblot Analyses

Proteins were transferred from SDS-polyacrylamide gels to Immobilon-P polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore). Membranes were blocked and probed with primary antibodies in non-fat milk to yeast mitochondrial proteins at the following dilutions: Coq1p, 1:10,000; Coq2p, 1:1,000; Coq3p, 1:1,000; Coq4p, 1:1,000; Coq5p, 1:5,000; Coq6p, 1:250; Coq7p, 1:5,000; Abc1/Coq8p, 1:100; Coq9p, 1:1,000; Coq10p, 1:200; Idh1p, 1:5,000; Rip1p, 1:10,000; Cyt b2, 1:5,000; Cyt c1, 1:1,000; Atp2p, 1:2,000; Hsp60p, 1:10,000 and Mdh1p, 1:10,000. Secondary antibodies, goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse (Calbiochem) were used at 1:10,000 dilutions. Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce) was used for illumination.

RESULTS

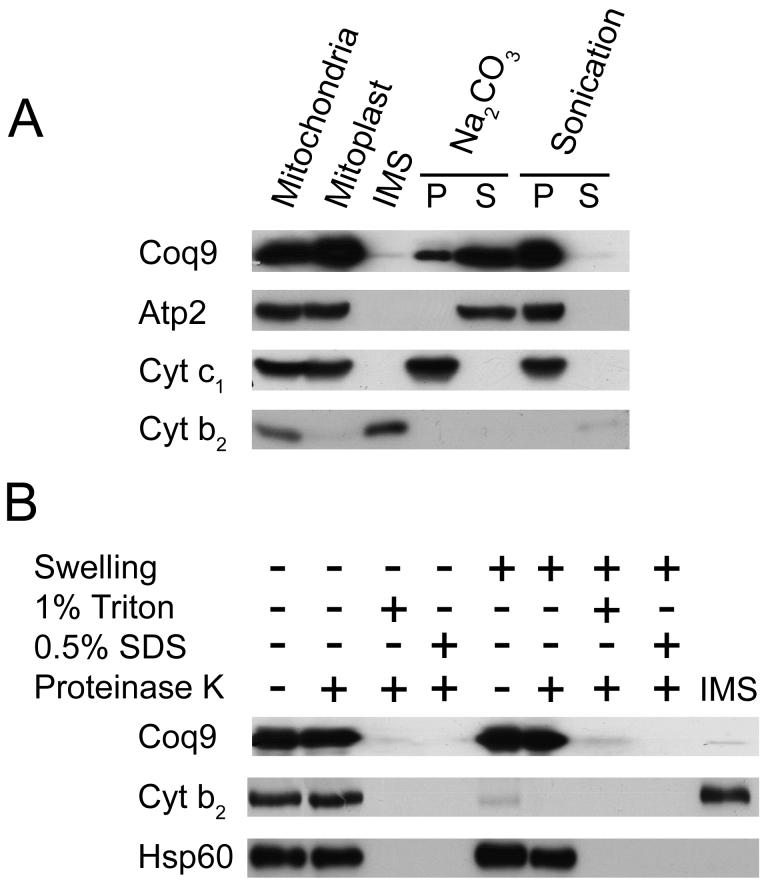

Coq9p is a peripheral membrane protein on the matrix side of the mitochondrial inner membrane

Studies of Coq9p fused to an HA tag have shown that it is localized to the inner membrane of mitochondria [1]. However, the degree of association with the inner membrane has not been examined. Moreover, it is important to determine the localization of the non-tagged Coq9 polypeptide. To investigate this, mitochondria were hypotonically shocked to generate mitoplasts. Mitoplasts were treated by sonication to separate membrane-associated proteins, or alkaline treated to extract peripheral membrane proteins. Coq9p remained with the membrane components after sonication and was released into the supernatant after alkaline treatment (Figure 1A). A proteinase K protection assay on purified mitochondria identified Coq9p as located on the matrix side of the inner mitochondrial membrane (Figure 1B). These data indicate Coq9p is a peripherally associated membrane protein on the matrix side of the mitochondrial inner membrane.

FIG. 1. Coq9p is peripherally associated to the inner mitochondrial membrane, facing toward the matrix side.

A) Mitochondria were subjected to hypotonic swelling and centrifugation to separate intermembrane space protein (IMS) and mitoplasts. The mitoplasts were either sonicated or treated with 0.1 M Na2CO3, pH 11.5, then separated via 100,000 × g centrifugation into pellet (P) or supernatant (S) fractions. B) Intact mitochondria or mitoplasts were treated with 100 μg/ml Proteinase K for 30 min on ice, in the presence or absence of detergent. Equal aliquots of pellets and TCA-precipitated soluble fractions were analyzed. Control polypeptide markers: (Atp2) β subunit of F1 ATPase, peripheral inner membrane; (Cyt b2) cytochrome b2, inter-membrane space; (Cyt c1) cytochrome c1, integral inner membrane; and (Hsp60), soluble matrix.

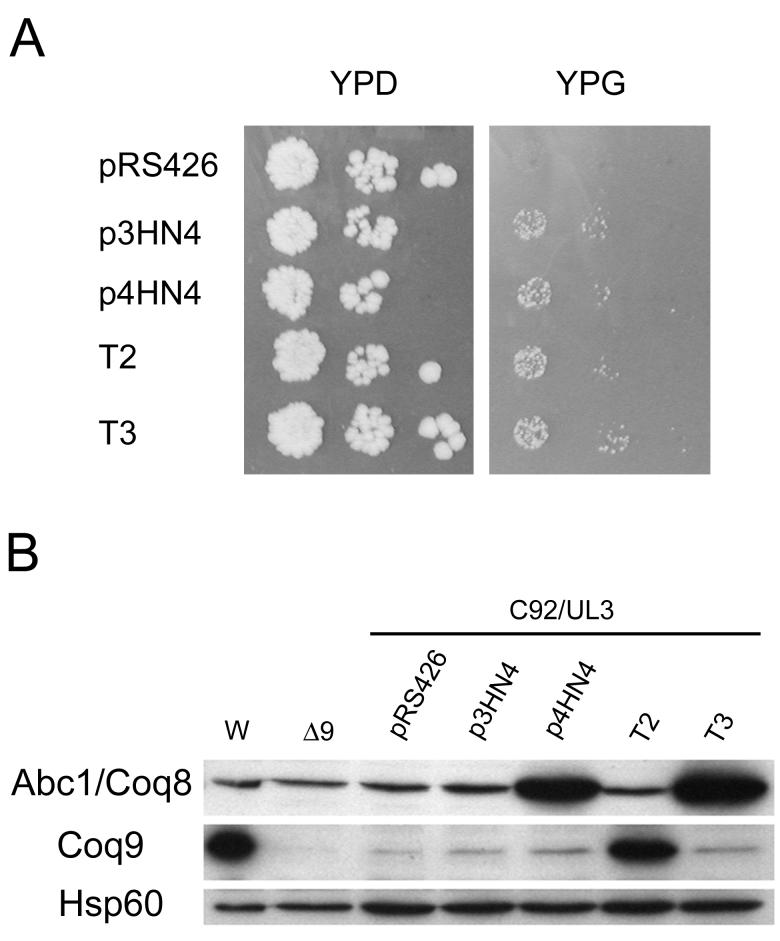

Identification of the mutation in coq9-1

The Q deficiency of the coq9-1 mutant was suppressed by the expression of ABC1/COQ8 in multicopy. The suppression was specific to the coq9-1 mutant strain as neither other coq9 mutants nor a coq9 null mutant were rescued by expression of ABC1/COQ8 [1]. Figure 2A shows that the coq9-1 mutant (C92/UL3) is rescued for growth on the nonfermentable carbon source YPG. Either multi- or low-copy plasmids containing the ABC1/COQ8 gene rescue, indicating that the suppression is effective at low copy. To examine the nature of this suppression, the coq9-1 allele was sequenced. Nucleotide sequencing identifies the mutation as a cytosine to thymine mutation at position +451. This results in a change of glutamine (CAA) at amino acid position 151 to a nonsense codon (TAA).

FIG. 2. Expression of ABC1/COQ8 on low- or multi-copy plasmids suppress yeast coq9-1 mutants.

A) The coq9-1 mutant, C92/UL3, is rescued for growth on the nonfermentable carbon source, glycerol, when transformed with ABC1/COQ8. The plasmids used were vector only (pRS426) or contained one of the following genes: ABC1/COQ8 (p3HN4, p4HN4 and T3) or COQ9 (T2). All plasmids are present in multicopy, except p3HN4, a low copy plasmid. B) Whole cell lysates of yeast (corresponding to 0.2 OD600nm) were analyzed by immunoblot with antisera against the indicated polypeptides. Cell lysates were prepared from W303-1A (W), W303ΔCOQ9 (Δ9) and the coq9-1mutant (C92/UL3) harboring the designated plasmids.

To investigate the suppression of the coq9-1 phenotype by ABC1/COQ8, whole cell lysates of coq9-1 yeast mutants harboring various plasmids were analyzed by immunoblot. Coq9p was detected at low levels in the C92/UL3 coq9-1 mutant, indicating read-through of the nonsense mutation. Expression of ABC1/COQ8 in the coq9-1 mutant did not significantly affect levels of Coq9p (Figure 2B). The data suggest that the suppression of coq9-1 by ABC1/COQ8 probably depends on a low level of the Coq9 polypeptide. However, the presence of Abc1/Coq8 does not serve to enhance steady state levels of Coq9p, and thus the suppression must operate independently of effects on read-through or steady state levels of Coq9p per se.

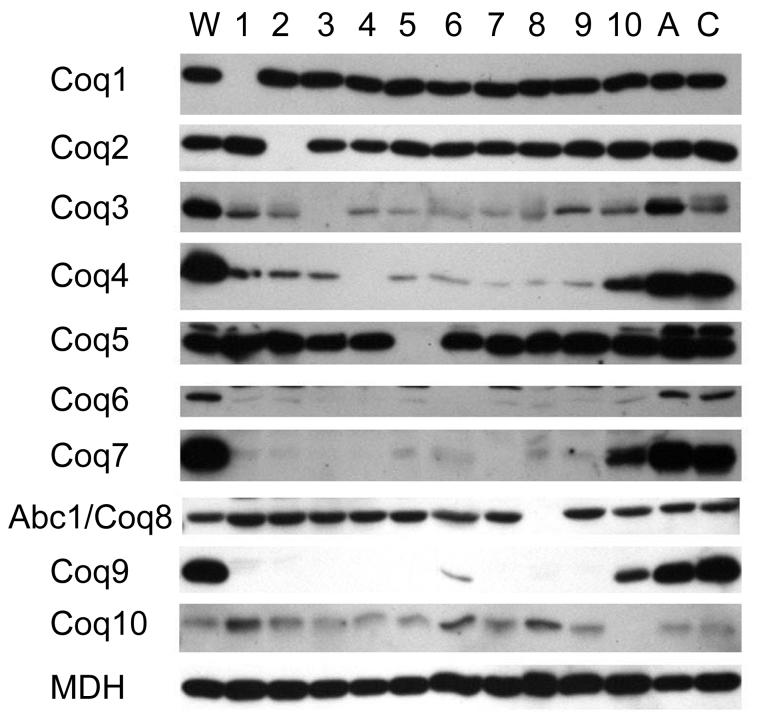

Coq9p steady state levels are diminished in coq mutants

Previous studies have investigated the effects of deletions in the COQ genes on the steady state protein levels of Coq1p, Coq3p, Coq4p, Coq5p and Coq6p [13-15]. In these studies, the steady state protein levels of Coq3p, Coq4p and Coq6p were decreased in yeast strains with deletions in the COQ genes, COQ1 - ABC1/COQ8. Recent evidence suggests that several Coq proteins form a complex and that Q or a Q biosynthetic intermediate may be a key component in maintaining its stability [13, 17]. To examine whether Coq2p, Coq7p, Abc1/Coq8p, Coq9p, or Coq10p, display a similar interdependence, mitochondria from coq1 - coq10 yeast mutant strains were prepared and analyzed on immunoblots with antisera against the Coq1 - Coq10 proteins (Figure 3). In the coq1 - coq9 mutant strains, Coq7p and Coq9p protein levels are dramatically decreased compared to wild-type mitochondria. This is similar to what has been observed for Coq3p, Coq4p and Coq6p. In contrast, steady state polypeptide levels of Coq1p, Coq2p, Coq5p, Abc1/Coq8p and Coq10p do not appear to be decreased in coq mutants. COQ10 encodes a protein that is not required for Q biosynthesis, but is required for function of Q in respiration and is believed to be involved in the transport or localization of Q [31]. The coq10 mutant has decreased levels of Coq3p, Coq4p, Coq6p, Coq7p and Coq9p relative to wild-type.

FIG. 3. Steady-state levels of the Coq proteins in mitochondria isolated from yeast strains harboring a deletion in one of the ten COQ genes, ATP2, or COR1.

Purified mitochondria (10 μg protein) were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Mitochondria were isolated from parental strain W303-1A (W), atp2 null mutant (A), cor1 null mutant (C) or from one of the indicated coq null mutant strains (1-10). Antibodies against malate dehydrogenase (MDH) were used to provide a control for equivalent loading.

In addition to strains with deletions in the coq1 - coq10 genes, strains with mutations in atp2 or cor1 were also examined. ATP2 encodes the β subunit of the F1 component of the mitochondrial ATP synthase and COR1 encodes a subunit of the bc1 complex. Although both are nuclear petite mutants, neither gene product is involved in Q biosynthesis. In the atp2 and cor1 mutants, each of the Coq polypeptides are present in an amount similar to wild-type, indicating that the decrease in polypeptide observed is specifically related to the loss of the COQ genes and is not a secondary effect of the loss of respiratory function.

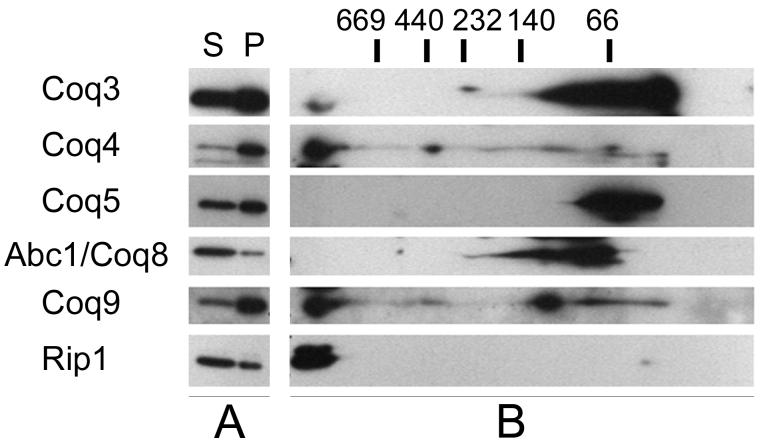

Coq9p co-localizes with other Coq polypeptides in a high molecular mass complex

Blue Native-PAGE was used to determine if Coq9p co-migrates with other Coq polypeptides under non-denaturing conditions. Wild-type mitochondria were solubilized with digitonin (Figure 4A) and separated under conditions that have been shown to preserve Coq proteins in high molecular mass complexes [16]. Digitonin-solubilized mitochondrial extracts were separated by Blue Native-PAGE, and sample lanes were then subjected to SDS-PAGE in a second dimension (Figure 4B). Immunoblot analyses shows Coq3p, Coq4p and Coq9p co-migrating at a molecular mass higher than the 669 kDa marker (Figure 4B). The migration of Coq3, Coq4 and Coq9 polypeptides correspond to that of Rip1, a component of the bc1 complex. Because Rip1 serves as a marker of respiratory supercomplexes in the mass range of 750 - 1000 kDa [32], we estimate that the mass of the complex containing Coq3, Coq4 and Coq9 as approximately 1 MDa. Coq5p and Abc1/Coq8p were not detected in the molecular mass range greater than 669 kDa.

FIG. 4. Coq9p co-migrates with Coq3p and Coq4p at high molecular mass in Blue Native-PAGE.

A) Solubility of Coq and Rip1 polypeptides were assessed by SDS-PAGE analysis. Purified wild-type mitochondria (200 μg protein) were solubilized with digitonin and subject to 100,000 × g centrifugation. (S) and (P) designate the supernatant and pellet of the digitonin-solubilized mitochondria, respectively. B) The digitonin-solubilized supernatant was subjected to 2-dimensional Blue Native gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting. Western blots were probed with antibodies against Coq3p, Coq4p, Coq5p, Abc1/Coq8p, Coq9p, and Rip1. Molecular mass standards are thyroglobulin (669 kD), ferritin (440 kD), catalase (232 kD), lactate dehydrogenase (140 kD) and bovine serum albumin (66 kD).

Coq4p, Coq5p, Coq6p and Coq7p co-precipitate with Coq9p-HA

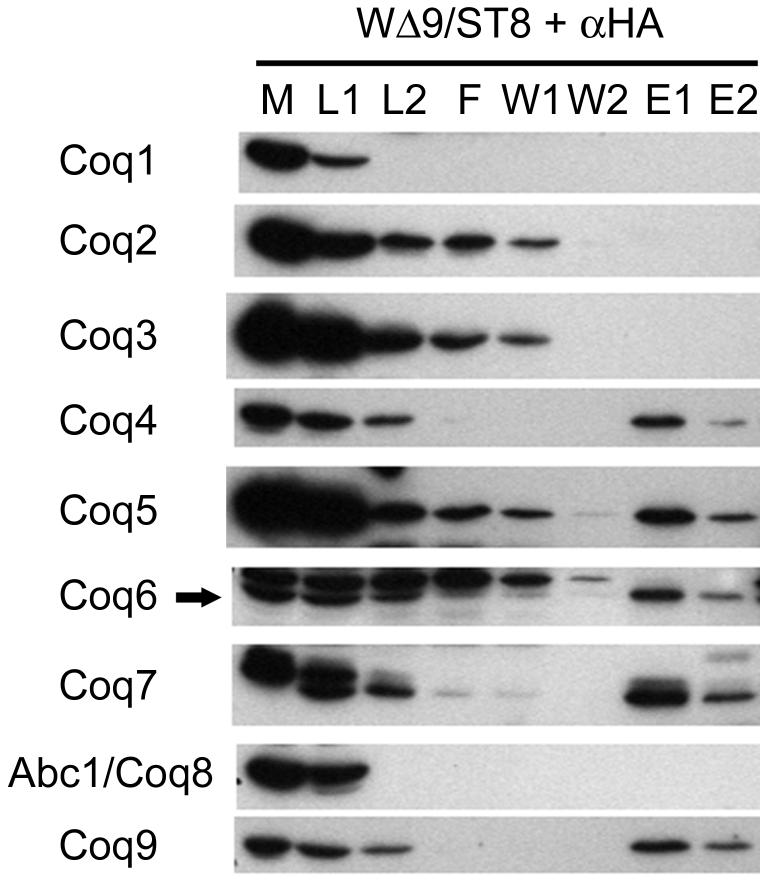

To identify interacting proteins, mitochondria were purified from a yeast strain expressing an integrated COQ9 gene with an HA tag and used for immunoprecipitation experiments. To the solubilized sample of mitochondria, a monoclonal anti-HA antibody conjugated to biotin was added. To precipitate the antibody and bound proteins, avidin-agarose beads were added. Antibodies to Coq9p were used to analyze the elutions from the avidin-agarose beads and verify immunoprecipitation of Coq9p. Western blots were probed with antibodies against Coq1p through Abc1/Coq8p. In the absence of the anti-body or the HA-tagged protein, no Coq proteins were visualized (data not shown). Coq4p, Coq5p, Coq6p and Coq7p were observed to co-precipitate with Coq9-HAp, whereas Coq1p, Coq2p, Coq3p and Abc1/Coq8p did not show evidence of co-immunoprecipitation (Figure 5). Coq1p and Abc1/Coq8p showed significant decreases in protein levels after the overnight incubation. This apparent proteolysis occurs despite the presence of protease inhibitors and incubation at low temperature.

FIG. 5. Coq4p, Coq5p, Coq6p and Coq7p co-immunoprecipitate with Coq9p-HA.

Digitonin-solubilized extracts of purified mitochondria from W303ΔCOQ9/ST8 (integrated COQ9 gene with an HA tag) were subjected to immunoprecipitation with monoclonal anti-HA antibodies conjugated to biotin, followed by addition of avidin-agarose beads. The agarose beads were washed twice before elution. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Purified mitochondria, (M); supernatant of solubilized mitochondria, (L1); samples after incubation with anti-HA antibodies, (L2); flowthrough, (F); washes 1 and 2, (W1/W2); elution with low pH buffer, (E1); and a second elution with SDS-PAGE sample buffer, (E2). 4% of the total protein content was loaded for each lane except for lanes E1 and E2, which represents 8% of total protein. Arrow indicates the Coq6 polypeptide.

DISCUSSION

COQ9 is the most recently identified gene that is required for Q biosynthesis in S. cerevisiae. Yeast mutants with null mutations in coq3 through coq9 accumulate HHB, the product of Coq2p and an early intermediate in the Q biosynthetic pathway [1]. This indicates that Coq9p must be acting in one or more of the steps required to convert HHB to Q. The lack of homology of Coq9p to characterized proteins makes it difficult to predict what biochemical function it may have. In order to learn more about Coq9 function, we have investigated the mechanism of suppression of a coq9-1 mutant by expression of ABC1/COQ8 (Figure 2A) and characterized several physical aspects of Coq9p. Nucleotide sequencing of the coq9-1 allele identified a nonsense mutation at Gln151. Immunoblot analyses of yeast cell lysates showed detectable full length Coq9 polypeptide, indicating a small amount of read-through of the nonsense mutation (Figure 2B). The coq9-1 mutant, when harboring plasmids expressing ABC1/COQ8, did not show increased levels of Coq9p. This indicates that the mechanism of suppression is not due to an increased level of read-through, but may be due to an increase in the amount of Abc1/Coq8p present. It is tempting to speculate that the Coq9 polypeptide may serve as a substrate of the putative kinase Abc1/Coq8, since this protein harbors kinase sequence motifs [19]. However, the mechanism of how Abc1/Coq8p is compensating for low levels of Coq9p is not known since no enzymatic activity of Abc1/Coq8p has been directly demonstrated.

Submitochondrial fractionation and proteinase K protection assays showed Coq9p is a peripheral membrane protein on the matrix side of the mitochondrial inner membrane (Figure 1). This localization is identical to the Coq proteins, Coq1p [13], Coq3p [33], Coq4p [34], Coq5p [14], Coq6p [6], Coq7p, 2 and Abc1/Coq8p.3 Immunoblot analyses of mitochondria show that Coq9p steady state protein levels are dramatically decreased by mutations in any of the other coq genes (Figure 3). The identical localization of Coq9p with other Q biosynthetic Coq proteins and the interdependence of Coq9p levels with other Coq proteins suggested that Coq9 might be a component of a Q biosynthetic protein complex.

In this study BN-PAGE separations of digitonin-solubilized mitochondrial extracts were performed to ascertain whether Coq9p migrated in the same high molecular mass complex as Coq3p and Coq4p (Figure 4B). BN-PAGE is a method of analyzing native molecular mass of proteins and has been used successfully to identify respiratory supercomplexes [32, 35]. A portion of Coq3p was present at a molecular mass greater than 669 kDa, but the majority of the polypeptide was located in a lower mass range between 66 kDa and 140 kDa. Coq4p and Coq9p were primarily present at the high mass range with Coq3p. Coq5p and Abc1/Coq8p were only detected in a lower molecular mass range between 66 kDa and 140 kDa. In the analysis of steady state protein levels in coq mutants, Coq5p and Abc1/Coq8p were not affected (Figure 3). One explanation for the absence of these polypeptides at higher molecular masses and for the independence of their steady state level from other coq mutations is that their interaction with the large protein complex is tenuous. Previous work has shown that in some cases the Coomassie dye used in BN-PAGE sample buffer can act as an anionic detergent and disrupt protein-protein interactions [36]; a similar phenomenon may be occurring here for Coq5p, since we have previously shown that Coq5p migrates as a complex of 669 kDa by size exclusion chromatography [16]. Alternatively, the absence of these polypeptides at high molecular weight may be due to poor solubility, perhaps another detergent, or altering conditions of pH and/or ionic strength might be important variables.

The interaction of Coq9p with other Coq proteins was investigated by immunoprecipitation of Coq9p-HA from digitonin-solubilized mitochondrial extracts. Antibodies against Coq proteins detected Coq4p, Coq5p, Coq6p and Coq7p co-precipitating in a specific manner with Coq9p-HA. Compared to the amount of Coq4p and Coq6p that associated with Coq9p, a smaller fraction of the total Coq5 polypeptide was associated with Coq9p. This is consistent with the hypothesis that the association of Coq5p with the other Coq proteins is less stable than the protein-protein interactions between the other Coq polypeptides. The results presented here suggest that Coq5p may be part of this protein complex that catalyzes Q biosynthesis. The co-precipitation results also corroborate the previous sizing experiments that show Coq4p, Coq5p, Coq6p and Coq7p migrate as a high molecular weight complex by BN-PAGE and/or gel filtration analysis [16, 17]. It was not possible to assess the association of Coq1p and Abc1/Coq8p with Coq9p by means of this immunoprecipitation experiments due to a unique susceptibility of Coq1p and Abc1/Coq8p to proteolysis in these extracts.

A Q biosynthetic complex would enhance catalytic efficiency and limit the release of potentially reactive Q intermediates. Quinones are capable of acting as electrophiles which can then modify other biological molecules, and may also be reduced by cellular reducing agents and in the process form semiquinone radicals which can generate superoxide [37, 38]. The desire to prevent the release of potentially reactive Q intermediates may explain why the steady state protein levels of some Coq proteins are decreased in coq mutants. In a coq mutant that is unable to complete Q biosynthesis, it might be favorable to degrade several Coq proteins and disrupt Q biosynthesis completely, rather than allow potentially dangerous intermediates to form.

Physical evidence that the Coq proteins form a complex was first shown by Marbois et al. in an analysis of Coq3p and Coq4p [16]. In that study, Coq3p and Coq4p were found to co-migrate in a molecular mass range of about 1 MDa. A physical interaction was shown by the co-immunoprecipitation of Coq4p and Coq3p fused to a biotin tag [16]. Given the association of Coq3 with Coq4, and their apparent co-migration by BN-PAGE (Figure 4B), it is curious that Coq3p was not detected in the immunoprecipitation of Coq9-HAp. In the BN-PAGE analysis, the proportion of Coq3p that is present in the large mass range is less than the amount of Coq3p present at the lower mass range. This may be an indication of a weak association with the complex. There are variations inherent in the experimental conditions between the native molecular mass determination and the immunoprecipitation experiments. It is also possible that the HA tag on Coq9 interfered with the capture of Coq3. Our studies of coq1 and coq7 yeast mutants suggest that Q or Q biosynthetic intermediates may have a role in maintaining steady state levels of some of the Coq polypeptides [13, 17], and hence complex formation. It is possible that a stable association of Coq9 with Coq3 during detergent isolations might require a higher concentration of Q or a Q-intermediate.

A limitation of the immunoblot detection of co-precipitating proteins is that the method demands a candidate polypeptide approach and the use of antisera. An alternative method of identifying co-eluting proteins is the separation of proteins in the elution by SDS-PAGE, followed by mass spectrometric analysis of protein bands. This method has the potential to identify novel polypeptide members of the Q biosynthetic complex. Identifying other partner proteins may provide additional clues to the functional role of Coq9p.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Alex Tzagoloff for generously providing us with the C92/UL3, W303ΔCOQ9 and W303ΔCOQ9/ST8 strains, the Coq10p antibody and for comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

- BN-PAGE

- Blue Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- HHB

- 3-hexaprenyl-4-hydroxybenzoic acid

- Q

- coenzyme Q or ubiquinone

U. C. Tran and C. F. Clarke, unpublished data

E. J. Hsieh and C. F. Clarke, unpublished data

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Johnson A, Gin P, Marbois BN, Hsieh EJ, Wu M, Barros MH, Clarke CF, Tzagoloff A. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:31397–31404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Turunen M, Olsson J, Dallner G. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1660:171–199. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ashby MN, Edwards PA. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:13157–13164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ashby MN, Kutsunai SY, Ackerman S, Tzagoloff A, Edwards PA. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:4128–4136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Barkovich RJ, Shtanko A, Shepherd JA, Lee PT, Myles DC, Tzagoloff A, Clarke CF. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:9182–9188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gin P, Hsu AY, Rothman SC, Jonassen T, Lee PT, Tzagoloff A, Clarke CF. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:25308–25316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Clarke CF, Williams W, Teruya JH. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:16636–16644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stenmark P, Grunler J, Mattsson J, Sindelar PJ, Nordlund P, Berthold DA. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:33297–33300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100346200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hsieh EJ, Dinoso JB, Clarke CF. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;317:648–653. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bousquet I, Dujardin G, Slonimski PP. Embo. J. 1991;10:2023–2031. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gibson F, Young IG. Methods Enzymol. 1978;53:600–609. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)53061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Poon WW, Do TQ, Marbois BN, Clarke CF. Mol. Aspects Med. 1997;18:S121–127. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(97)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gin P, Clarke CF. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:2676–2681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Baba SW, Belogrudov GI, Lee JC, Lee PT, Strahan J, Shepherd JN, Clarke CF. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:10052–10059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313712200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hsu AY, Do TQ, Lee PT, Clarke CF. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1484:287–297. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Marbois B, Gin P, Faull KF, Poon WW, Lee PT, Strahan J, Shepherd JN, Clarke CF. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:20231–20238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501315200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tran UC, Marbois B, Gin P, Gulmezian M, Jonassen T, Clarke CF. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:16401–16409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513267200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Cherukuri PF, DeWeese-Scott C, Geer LY, Gwadz M, He S, Hurwitz DI, Jackson JD, Ke Z, Lanczycki CJ, Liebert CA, Liu C, Lu F, Marchler GH, Mullokandov M, Shoemaker BA, Simonyan V, Song JS, Thiessen PA, Yamashita RA, Yin JJ, Zhang D, Bryant SH. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D192–196. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Leonard CJ, Aravind L, Koonin EV. Genome Res. 1998;8:1038–1047. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.10.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Burke D, Dawson D, Stearns T. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Course Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yaffe MP, Schatz G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:4819–4823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.15.4819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Glick BS, Pon LA. Methods Enzymol. 1995;260:213–223. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)60139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jonassen T, Proft M, Randez-Gil F, Schultz JR, Marbois BN, Entian KD, Clarke CF. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:3351–3357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jarosch E, Tuller G, Daum G, Waldherr M, Voskova A, Schweyen RJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:17219–17225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Glick BS, Brandt A, Cunningham K, Muller S, Hallberg RL, Schatz G. Cell. 1992;69:809–822. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90292-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kemp HA, Sprague GF., Jr. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:1750–1763. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1750-1763.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Laemmli UK. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Schagger H, von Jagow G. Anal. Biochem. 1991;199:223–231. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90094-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Pauli D, Tonka CH, Tissieres A, Arrigo AP. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:817–828. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Garfin DE. Methods Enzymol. 1990;182:425–441. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Barros MH, Johnson A, Gin P, Marbois BN, Clarke CF, Tzagoloff A. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:42627–42635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Schagger H, Pfeiffer K. Embo. J. 2000;19:1777–1783. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Poon WW, Barkovich RJ, Hsu AY, Frankel A, Lee PT, Shepherd JN, Myles DC, Clarke CF. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21665–21672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Belogrudov GI, Lee PT, Jonassen T, Hsu AY, Gin P, Clarke CF. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;392:48–58. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Arnold I, Pfeiffer K, Neupert W, Stuart RA, Schagger H. Embo. J. 1998;17:7170–7178. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Krause F. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:2759–2781. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].O’Brien PJ. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1991;80:1–41. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(91)90029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Rodriguez CE, Shinyashiki M, Froines J, Yu RC, Fukuto JM, Cho AK. Toxicology. 2004;201:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Do TQ, Schultz JR, Clarke CF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1996;93:7534–7539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Marbois BN, Clarke CF. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:2995–3004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Okada K, Kamiya Y, Zhu X, Suzuki K, Tanaka K, Nakagawa T, Matsuda H, Kawamukai M. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:5992–5998. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.5992-5998.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].McEwen JE, Ko C, Kloeckner-Gruissem B, Poyton RO. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:11872–11879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]