Abstract

Previous research from our laboratory has implicated the basolateral amygdala (BLA) complex in the acquisition and consolidation of cue-cocaine associations, as well as extinction learning, which may regulate the long-lasting control of conditioned stimuli (CS) over drug-seeking behavior. Given the well established role of NMDA glutamate receptor activation in other forms of amygdalar-based learning, we predicted that BLA-mediated drug-cue associative learning would be NMDA receptor dependent. To test this hypothesis, male Sprague-Dawley rats self-administered i.v. cocaine (0.6 mg/kg/infusion) in the absence of explicit CS pairings (2-h sessions, 5 days), followed by a single 1-h classical conditioning (CC) session, during which they received passive infusions of cocaine discretely paired with a light+tone stimulus complex. Following additional cocaine self-administration sessions in the absence of the CS (2-h sessions, 5 days) and extinction training sessions (no cocaine or CS presentation, 2-h sessions, 7 days), the ability of the CS to reinstate cocaine-seeking on three test days was assessed. Rats received bilateral intra-BLA infusions (0.5 μl/hemisphere) of vehicle or the selective NMDA receptor antagonist, 2-amino-5-phosphonovalerate (AP-5), immediately prior to the CC session (acquisition), immediately following the CC session (consolidation), or immediately following reinstatement testing (consolidation of conditioned-cued extinction learning). AP-5 administered before or after CC attenuated subsequent CS-induced reinstatement, whereas AP-5 administered immediately following the first two reinstatement tests impaired the extinction of cocaine-seeking behavior. These results suggest that NMDA receptor-mediated mechanisms within the BLA play a crucial role in the consolidation of drug-CS associations into long-term memories that, in turn, drive cocaine-seeking during relapse.

Keywords: amygdala, NMDA, glutamate, cocaine, relapse, reinstatement

Introduction

One of the most significant problems for the long-term treatment of drug dependence is the high propensity of users to relapse to drug-seeking and drug-taking behaviors following prolonged periods of abstinence from drug use (Dackis and O'Brien, 2001; Wagner and Anthony, 2002). Of particular note, abstinent cocaine users often report intense drug craving when exposed to stimuli that have been previously associated with the drug of abuse (Childress, Hole, Ehrman, Robbins, McLellan, and O'Brien, 1993; Ehrman, Robbins, Childress, and O'Brien, 1992; Volkow, Wang, Telang, Fowler, Logan, Childress, Jayne, Ma, and Wong, 2006). Through the process of associative learning, previously neutral stimuli acquire incentive motivational value when repeatedly paired with drug use, and encounters with these conditioned stimuli (CS) may serve as environmental triggers of relapse to cocaine use (Wallace, 1989). Similarly, exposing animals to CS following withdrawal from chronic cocaine self-administration will robustly reinstate drug-seeking as measured by responding on a previously cocaine-paired lever (de Wit and Stewart, 1981; Meil and See, 1996; Shaham, Shalev, Lu, De Wit, and Stewart, 2003). The reinstatement model of relapse has not only allowed for the testing of compounds that may prevent relapse in abstinent drug users (Feltenstein, Altar, and See, 2007; Heidbreder, 2005), but has provided a model for extensive exploration of the neural circuitry that underlies conditioned cues and their role in relapse (Kruzich and See, 2001; Meil and See, 1997; Neisewander, Baker, Fuchs, Tran-Nguyen, Palmer, and Marshall, 2000; Weiss, Maldonado-Vlaar, Parsons, Kerr, Smith, and Ben-Shahar, 2000).

One neural substrate of particular interest in the study of cue-induced relapse is the basolateral complex of the amygdala (BLA). Using brain imaging techniques, a number of studies have noted an increase in amygdala activity when abstinent cocaine users are presented with drug-associated cues or drug-related imagery (Bonson, Grant, Contoreggi, Links, Metcalfe, Weyl, Kurian, Ernst, and London, 2002; Breiter, Gollub, Weisskoff, Kennedy, Makris, Berke, Goodman, Kantor, Gastfriend, Riorden, Mathew, Rosen, and Hyman, 1997; Childress, Mozley, McElgin, Fitzgerald, Reivich, and O'Brien, 1999; Grant, London, Newlin, Villemagne, Liu, Contoreggi, Phillips, Kimes, and Margolin, 1996; Kilts, Gross, Ely, and Drexler, 2004; Kilts, Schweitzer, Quinn, Gross, Faber, Muhammad, Ely, Hoffman, and Drexler, 2001). Consistent with these findings, studies in rodent models using excitotoxic lesions (Meil and See, 1997) or reversible pharmacological inactivation (Grimm and See, 2000; Kantak, Black, Valencia, Green-Jordan, and Eichenbaum, 2002; McLaughlin and See, 2003) have shown the importance of the BLA in the expression of conditioned-cued reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. However, in contrast to the fairly extensive studies of amygdalar substrates of fear conditioning (Davis, Rainnie, and Cassell, 1994; LeDoux, 2000), the role of the BLA in the acquisition and consolidation of drug-cue memories has only recently begun to be explored.

In order to assess the dynamic process of stimulus-cocaine associative learning, we developed a paradigm whereby stimuli are discretely paired with i.v. cocaine infusions during a classical conditioning session in rats with prior cocaine self-administration experience (Kruzich, Congleton, and See, 2001; See, 2005). Based on a single session, these stimuli will later reinstate drug-seeking long after their initial presentation and after prolonged withdrawal from cocaine. Using this procedure, we have demonstrated that sodium channel blockade with tetrodotoxin (Kruzich and See, 2001), a muscarinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist (See, McLaughlin, and Fuchs, 2003), or dopamine receptor antagonists (Berglind, Case, Parker, Fuchs, and See, 2006) within the BLA disrupt the acquisition of cocaine-stimulus associations, as evidenced by attenuation of conditioned-cued reinstatement. More recently, we have also applied this appetitive learning paradigm to demonstrate that the BLA is important in the consolidation of cocaine-cue associative learning, since neuronal inactivation after the classical conditioning session attenuated subsequent conditioned-cued reinstatement (Fuchs, Feltenstein, and See, 2006b). Thus, the BLA is not only important during the expression of reinstatement of drug-seeking, but also for the acquisition and consolidation of cocaine-cue associations that can maintain cocaine-seeking during relapse.

The BLA has a large concentration of glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (Monaghan and Cotman, 1985) and a substantial amount of evidence suggests these receptors are critical for the formation of learned associations. For example, microinfusions of NMDA receptor antagonists (e.g., AP-5 or MK-801) into the BLA have been found to inhibit both the initial acquisition (Goosens and Maren, 2003; Lee and Kim, 1998; Maren, Aharonov, Stote, and Fanselow, 1996; Walker, Paschall, and Davis, 2005) and extinction (Lee and Kim, 1998; Lee, Milton, and Everitt, 2006) of conditioned fear behaviors. Similar effects have been noted for the acquisition (Ferry and Di Scala, 2000; Hatfield and Gallagher, 1995; Liang, Hon, and Davis, 1994) and consolidation (Ferry and Di Scala, 2000; Liang et al., 1994) of associative learning in other tasks, including the inhibitory avoidance task and taste-potentiated odor aversion. AP-5 administration into the BLA has also been found to inhibit the acquisition of learning in appetitive tasks, such as appetitive instrumental learning (Baldwin, Holahan, Sadeghian, and Kelley, 2000) and discriminative approach behaviors to an appetitive CS (Burns, Everitt, and Robbins, 1994). While our laboratory has previously shown that NMDA receptors in the BLA are not necessary for the expression of conditioned-cued reinstatement (See, Kruzich, and Grimm, 2001), it is unknown whether NMDA receptors are involved in the formation of CS-cocaine associations. Thus, the current study examined whether NMDA receptor antagonism in the BLA would impair the acquisition and/or consolidation of stimulus-reward associations and conditioned-cued extinction learning in an animal model of relapse.

Methods and Materials

Subjects

Male, Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 32, initial weight 250-275 g; Charles River, Wilmington, MA, USA) were individually housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium on a 12-h reverse light-dark cycle (lights off 6 AM-6 PM). Animals were given water ad libitum and were maintained on 25 g of standard rat chow (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) per day for the duration of each experiment. Rats were acclimated to handling and allowed to adapt for a minimum of three days prior to the start of the experiment. Housing and care of the rats were carried out in accordance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Rats” (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources on Life Sciences, National Research Council, 1996).

Lever response training

Rats were trained to lever press in standard self-administration chambers (30 × 20 × 20 cm) linked to a computerized data collection program (MED-PC, Med Associates, Inc., St. Albans, VT, USA). The chambers were equipped with two retractable levers, a white stimulus light above each lever, a food pellet dispenser between the levers, a tone generator (ENV-223HAM, Med Associates), and a house light on the wall opposite the levers. Each chamber was contained within a sound-attenuating cubicle equipped with a ventilation fan. Forty-eight hours prior to surgery, rats were food deprived overnight and trained to lever press along a fixed ratio (FR) 1 schedule of reinforcement (45 mg pellets; Noyes, Lancaster, NH, USA) during a 15-h overnight training session in the absence of explicit conditioned stimulus (CS) presentation (i.e., active lever presses resulted in the delivery of a food pellet only). Lever presses on an inactive lever were recorded, but had no programmed consequence. Following lever response training, food dispensers were permanently removed from the test chambers.

Surgery

Rats were anesthetized using a mixture of ketamine hydrochloride and xylazine (66 and 1.33 mg/kg, respectively, IP) followed by equithesin (0.5 ml/kg with a solution of 9.72 mg/ml pentobarbital sodium, 42.5 mg/ml chloral hydrate, and 21.3 mg/ml magnesium sulfate heptahydrate dissolved in a 44% propylene glycol, 10% ethanol solution, IP). Surgical procedures were conducted using aseptic techniques. Catheters were constructed using previously described methods (Fuchs, Evans, Parker, and See, 2004) and consisted of external guide cannulae with screw-type connectors (Plastics One, Inc., Roanoke, VA, USA), Silastic tubing (10 cm; ID = 0.64 mm; OD = 1.19 mm; Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA), prolite polypropylene monofilament mesh (2 cm diameter, Atrium Medical Corporation, Hudson, NH, USA), and cranioplastic cement. A small incision was made on the back and chest of the rat 5 mm above the area where the jugular vein enters the rib cage. The external guide cannula exited from the incision on the rat's back and the open end of the Silastic tubing was passed subcutaneously to the area of the jugular vein. The free end of the tubing was inserted 33 mm into the right jugular vein and secured with 4.0 silk sutures. Both incisions were sutured with 4.0 sterile surgical thread.

Immediately after the catheter surgery, the rats were placed into a stereotaxic instrument (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA). Bilateral stainless-steel guide cannulae (26 gauge, Plastics One, Inc.) were aimed 2 mm dorsal to the BLA (-2.7 mm AP, ± 5.0 mm ML, -6.6 mm DV) using standard stereotaxic procedures. Three small screws and cranioplastic cement secured the guide cannulae to the skull. Stylets (Plastics One, Inc.) were placed into the guide cannulae and catheter to prevent occlusions. To maintain catheter patency, catheters were flushed once daily for 4 days after surgery with 0.1 ml each of an antibiotic solution of cefazolin (100 mg/ml; Schein Pharmaceuticals, Florham Park, NJ, USA) dissolved in heparinized saline (70 U/ml; Elkins-Sinn, Cherry Hill, NJ, USA) and heparinized saline. For the duration of the experiment, each subject then received 0.1 ml of heparinized saline (10 U/ml) immediately prior to self-administration sessions and the cefazolin and 70 U/ml heparinized saline regimen following each session. To verify catheter patency, rats occasionally received a 0.12 ml infusion of methohexital sodium (10.0 mg/ml IV; Eli Lilly and Co., Indianapolis, IN, USA), a short-acting barbiturate that produces a rapid loss of muscle tone when administered intravenously.

Cocaine self-administration and classical conditioning

Fig.1 illustrates the phases of training and testing, and when the microinfusions occurred. Rats self-administered cocaine (cocaine hydrochloride dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline; cocaine provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) during daily 2-h sessions according to an FR 1 schedule of reinforcement. At the start of each session, the catheter was connected to a liquid swivel (Instech, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA) via polyethylene 20 tubing that was encased in steel spring leashes (Plastics One, Inc.). The swivels were suspended above the self-administration chamber and were connected to infusion pumps (model PHM-100, Med-Associates). The house light signaled the initiation of the session and remained illuminated throughout the entire session. Lever presses on the active lever resulted in a 2-s activation of the infusion pump (0.6 mg/kg cocaine per 50 μl infusion) in the absence of explicit CS presentation (i.e., active lever presses resulted in the delivery of cocaine only). After each infusion, responses on the active lever had no consequences during a 20-s time-out period. During the sessions, responses on the inactive lever were recorded, but had no programmed consequences. Daily self-administration sessions continued until each rat had obtained the initial self-administration criterion of five sessions with at least ten infusions per session.

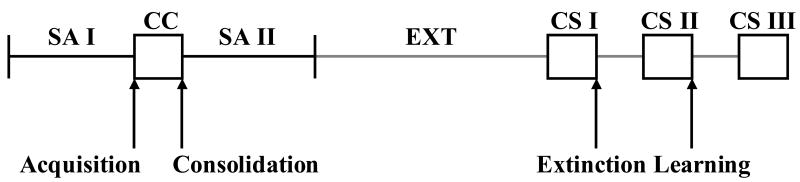

Figure 1.

Schematic representing the phases of cocaine self-administration training (SA I and II), the classical conditioning session (CC), extinction (EXT), and CS reinstatement testing (CS I, II, and III). Arrows indicate when the bilateral intra-BLA microinfusions occurred. Animals in the acquisition and consolidation groups received their microinfusions immediately prior to and following the CC session, respectively, and underwent a single CS test. Animals in the consolidation of extinction learning group all received vehicle treatment at the time of the CC session (either at acquisition or consolidation) and then received subsequent microinfusions (either AP-5 or vehicle) immediately after each of the first two reinstatement tests.

Twenty-four hours after the last day of initial cocaine self-administration training, rats underwent a single 1-h classical conditioning (CC) session in the self-administration chamber. During this session, rats received passive infusions (i.e., levers were retracted) of cocaine and simultaneous 5-s presentations of a stimulus complex, consisting of activation of the stimulus light above the active lever and the tone generator (78 dB, 4.5 kHz). The number of pairings equaled the mean number of cocaine infusions earned during the first hour of the preceding two self-administration days as calculated for each individual rat.

CS-induced reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking

To investigate the role of NMDA receptors in the BLA in the acquisition and consolidation of CS-cocaine associations, rats received bilateral intra-BLA microinfusions (0.5 μl/hemisphere) of the selective NMDA receptor antagonist d-AP-5 (Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO, USA) immediately prior to (0, 3, or 10 μg) or immediately following (0 or 3 μg) the CC session, respectively. The vehicle consisted of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Injection cannulae (33 gauge, Plastics One, Inc.) were inserted to a depth of 2 mm past the tip of the guide cannulae and remained in place for 2 min during the infusion and for 1 min both before and after the infusion.

After the CC session, rats underwent 5 additional days of cocaine self-administration sessions in the absence of explicit CS presentation. Subsequently, rats underwent daily 2-h extinction training, during which responses on both levers were recorded, but had no programmed consequences. Once the extinction criterion was reached (i.e., a minimum of seven extinction sessions with ≤ 25 active lever responses per session for 2 consecutive days), CS-induced reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior was assessed. During the 2-h reinstatement test session, responses on the active lever resulted in a 5-s presentation of the light + tone stimulus complex, followed by a 20-s time out, in the absence of cocaine reinforcement.

In our recent study, administration of TTX immediately following the first CS reinstatement test prevented the extinction of cocaine-seeking behavior on a subsequent reinstatement test (Fuchs et al., 2006b), suggesting that the BLA also plays an important role in conditioned-cued extinction memory consolidation. To investigate the role of NMDA receptors in the BLA in CS extinction memory consolidation, rats that had previously received vehicle treatment at the time of the CC session (either at acquisition or consolidation) were assigned to receive bilateral intra-BLA microinfusions (0.5 μl/hemisphere) of AP-5 (3 μg) or vehicle immediately after each of the first two reinstatement tests. Daily 2-h extinction sessions occurred between each reinstatement test to criterion.

Histology and data analysis

After all testing was completed, rats were transcardially perfused with PBS and 10% formaldehyde solution. The brains were dissected and stored in 10% formaldehyde solution prior to sectioning. Using a vibratome (Technical Products International, St. Louis, MO, USA), brains were sectioned in the coronal plane (75 μm thickness), mounted on gelatin-coated slides, and stained for Nissl substance with cresyl violet (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA). The sections were examined under a light microscope using 10x magnification. The most ventral point of the microinjector tips were mapped onto schematics of the appropriate plates using a rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 1997). Analyses of active and inactive lever responding and cocaine intake during self-administration, number of CC pairings, and lever responses during extinction and CS reinstatement testing were conducted using one- or two-way repeated measures ANOVA and one-way ANOVA or t tests, where appropriate.

Results

Cocaine self-administration, classical conditioning, and extinction

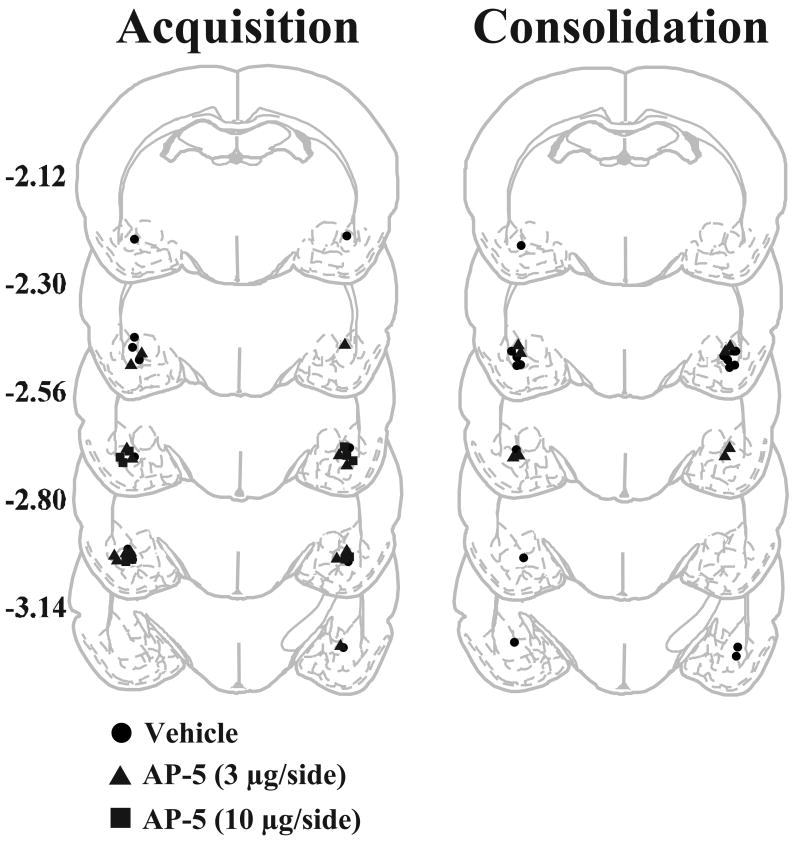

Schematic representations of the most ventral point of bilateral BLA injection cannulae for animals in the acquisition-vehicle (n = 6), acquisition-3 μg AP-5 (n = 6), acquisition-10 μg AP-5 (n = 5), consolidation-vehicle (n = 9) and consolidation-3 μg AP-5 (n = 6) groups are indicated in Fig. 2. Data for active and inactive lever responding are shown across the various experimental phases for the acquisition (Fig. 3) and consolidation (Fig. 4) groups. Both groups of rats readily acquired cocaine self-administration, responded preferentially on the active lever, and displayed stable lever responding and cocaine intake by the end of the first five days of self-administration. Data analyses failed to reveal any significant pre-existing treatment group differences in active or inactive lever responding or daily cocaine intake for animals in the acquisition group (F 2,14 = 0.70-1.32, P = 0.30-0.51). Similar analyses for animals in the consolidation group also revealed no significant treatment group differences in active or inactive lever responding or cocaine intake (t 13 = 0.16-0.83, P = 0.42-0.87). Following the first phase of cocaine self-administration, all animals underwent a 1-h CC session. No significant differences in the number of CS-cocaine pairings (mean ± SEM) were noted for animals in the acquisition (vehicle = 10.50 ± 2.25, 3μg AP-5 = 13.00 ± 1.92, 10 μg AP-5 = 13.80 ± 0.7, F 2,14 = 0.86, P = 0.44) or the consolidation (vehicle = 14.67 ± 1.95, 3 μg AP-5 = 10.83 ± 1.49, t 13 = 1.43, P = 0.18) groups. Moreover, data analyses failed to reveal any significant treatment group differences in active or inactive lever responding or cocaine intake during the second phase of cocaine self-administration training, nor were any treatment group differences found for active or inactive lever responding at the end of extinction training for animals in the acquisition (F 2,14 = 0.34-1.49, P = 0.26-0.72) or the consolidation groups (t 13 = 0.59-1.53, P = 0.15-0.57).

Figure 2.

Coronal sections (adapted from Paxinos and Watson, 1986) with graphical representations of cannula tip placements in the BLA. Numbers to the left of the sections indicate A/P distance from bregma in mm.

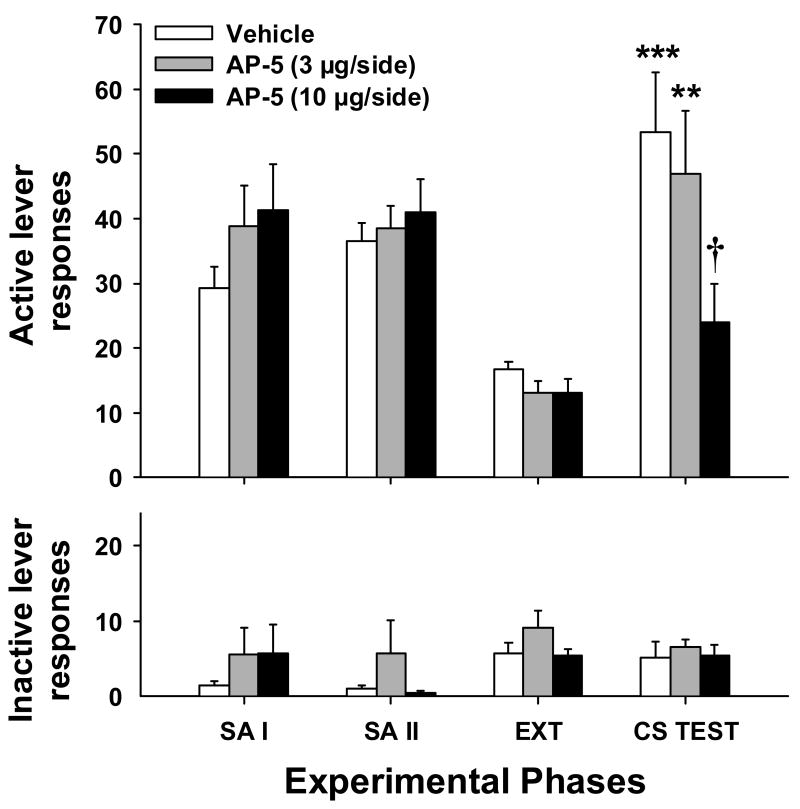

Figure 3.

Mean (±SEM) active (top panel) and inactive (bottom panel) lever responses for the last 2 days of self-administration (SA) phases I and II, extinction (EXT), and during the CS reinstatement test. Animals received bilateral intra-BLA infusions of vehicle or AP-5 immediately prior to the CC session (acquisition). Significant differences are indicated as compared to extinction levels (***P < 0.005; **P < 0.01) or vehicle (†P < 0.05).

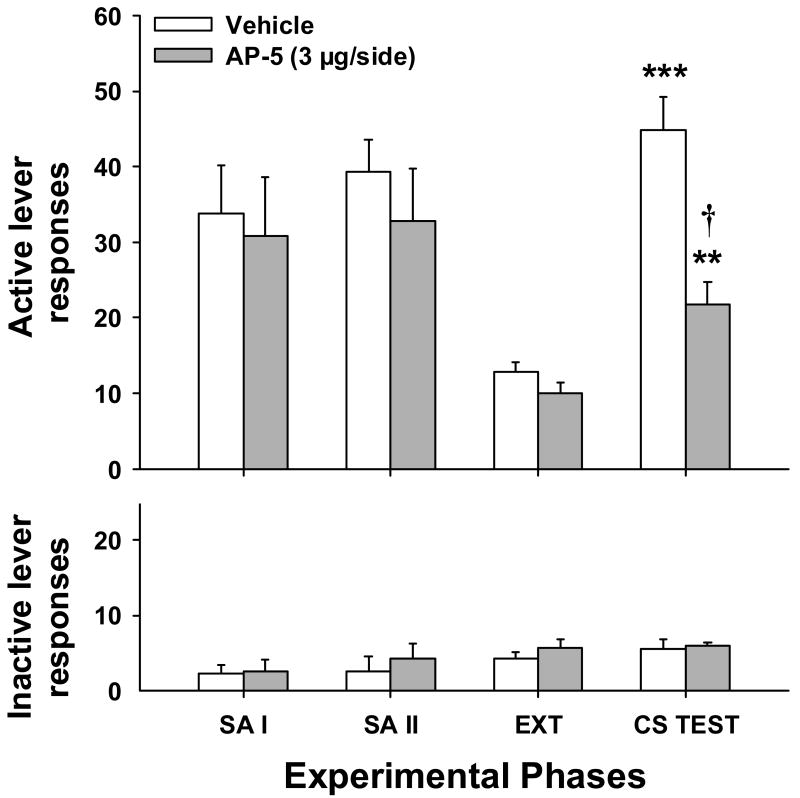

Figure 4.

Mean (±SEM) active (top panel) and inactive (bottom panel) lever responses for the last 2 days of self-administration (SA) phases I and II, extinction (EXT), and during the CS reinstatement test. Animals received bilateral intra-BLA infusions of vehicle or AP-5 immediately after the CC session (consolidation). Significant differences are indicated as compared to extinction levels (***P < 0.005; **P < 0.01) or vehicle (†P < 0.05).

CS reinstatement testing

Following extinction training, exposure to the cocaine-paired CS led to a selective increase in responding on the previously drug-paired lever, an effect that was dose-dependently attenuated by pre-CC infusions of AP-5 in the BLA (Fig. 3). Active lever responding during the conditioned-cued reinstatement test was significantly increased over extinction in the vehicle-treated (t 10 = 3.96, P < 0.005) and the 3 μg AP-5 (t 10= 3.36, P < 0.01) groups, but did not significantly differ from extinction level responding for animals in the 10 μg AP-5 group (t 8= 1.75, P = 0.12). Compared to the vehicle group, animals that received 10 μg AP-5 (t 9= 2.56, P < 0.05), but not 3 μg AP-5 (t 10= 0.48, P = 0.64), showed a significant attenuation in CS-induced reinstatement. Finally, there were no significant group differences in inactive lever responding during reinstatement testing for animals in the acquisition groups.

As seen in Fig. 4, vehicle-treated animals in the consolidation group showed a significant increase in active lever responding, relative to extinction responding, during the CS reinstatement test (t 13 = 6.90, P < 0.001). Moreover, this effect was attenuated when AP-5 (3 μg) was selectively infused into the BLA (t 13 = 3.83, P < 0.005). Although significantly reduced relative to the vehicle group, CS-reinstatement was not completely abolished, since AP-5 treated rats did show higher responding over extinction levels (t 10 = 3.70, P < 0.005). There were also no significant group differences in inactive lever responding during CS reinstatement testing for animals in the consolidation groups.

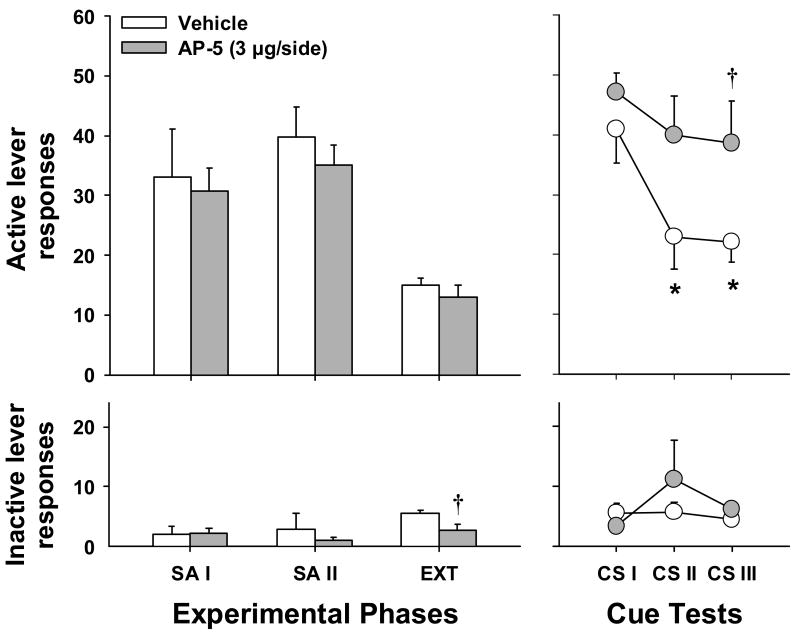

CS extinction memory consolidation

Fig. 5 shows active and inactive lever responding for animals assigned to receive post-CS reinstatement testing infusions of vehicle (n = 7) or AP-5 (n = 6). Statistical analyses showed no significant pre-existing treatment group differences in active lever responding or cocaine intake during cocaine self-administration, extinction, or the first CS reinstatement test (t 11 = 0.27-0.90, P = 0.39-0.80). Moreover, no significant differences in the number of CS-cocaine pairings (mean ± SEM) were noted (vehicle = 14.71 ± 2.52, 3 μg AP-5 = 11.83 ± 1.97, t11 = 0.88, P = 0.40). Similar analyses for inactive lever responding only revealed a modest, but significant difference between these groups at the end of extinction training (t 11 = 2.78, P < 0.05). A two-way repeated measures ANOVA on the CS reinstatement data revealed main effects for group (F1,11 = 5.02, P < 0.05) and test (F 2,22= 6.78, P = 0.005). The group x test interaction was not significant. Further one-way repeated measures ANOVA for each group showed a significant test effect for animals that received vehicle (F 2,12 = 11.03, P < 0.005), but not AP-5 (F 2,10 = 0.81, P = 0.47). For animals in the vehicle group, post-hoc comparisons of subsequent tests to CS test 1 revealed a significant decrease in active lever responding on both the second (t 12 = 2.29, P < 0.05) and third (t 12 = 2.81, P < 0.05) tests. Relative to extinction responding, rats that received intra-BLA vehicle infusions exhibited extinction learning across tests, as seen by a significantly higher level of active lever responding on the first CS-reinstatement test (t 12 = 4.43, P < 0.001), but not on subsequent tests (t 12 = 0.91-1.66, P = 0.12-0.38). In contrast, rats that received intra-BLA infusions of AP-5 immediately after the CS-reinstatement test maintained significantly higher responding over extinction levels (t 10 = 2.93-8.89, P < 0.001-0.05). Relative to vehicle-treatment, intra-BLA infusions of AP-5 just after the previous test led to significantly greater active lever responding on the last CS-reinstatement test (t 11 = 2.23, P < 0.05). Finally, no significant group differences in inactive lever responding were seen during CS-reinstatement testing or intervening extinction days.

Figure 5.

LEFT: Mean (±SEM) active (top panel) and inactive (bottom panel) lever responses for the last 2 days of self-administration (SA) phases I and II and extinction (EXT). All animals received vehicle during the initial CC session. RIGHT: Mean (±SEM) active (top panel) and inactive (bottom panel) lever responses during the three CS reinstatement tests. Animals received bilateral intra-BLA infusions of vehicle or AP-5 immediately after the first and second CS tests. Significant differences are indicated as compared to CS I (*P < 0.05) or vehicle (†P < 0.05).

Discussion

Previous research has implicated the BLA in the process of neutral stimuli acquiring incentive-motivational properties when paired with reward (Cador, Robbins, and Everitt, 1989; Everitt, Parkinson, Olmstead, Arroyo, Robledo, and Robbins, 1999; Hatfield, Han, Conley, Gallagher, and Holland, 1996; Whitelaw, Markou, Robbins, and Everitt, 1996). As we have previously demonstrated (Fuchs et al., 2006b), exposure to CS-cocaine pairings during a single 1-h CC session subsequently led to robust reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior (i.e., increased responding on the previously cocaine-paired lever) in vehicle-treated animals. Intra-BLA blockade of NMDA receptors by AP-5 at the time of either acquisition or consolidation significantly disrupted cocaine-CS associative learning as seen by the decrease in conditioned-cued reinstatement, although disruption of acquisition required a higher concentration of AP-5. When given immediately following a series of CS-reinstatement tests, AP-5 also attenuated the extinction of CS-induced cocaine-seeking behavior that normally occurs following exposure to non-reinforced CS presentations (i.e., the consolidation of CS-no cocaine associations). Thus, the current results show that NMDA receptor mediated activity in the BLA plays an important role in the associative learning of environmental stimuli relevant to cocaine-seeking behavior.

The current results are consistent with our previous work, which found that post-CC session inactivation of the BLA by the Na+-channel blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX) led to an attenuation of CS-induced reinstatement (Fuchs et al., 2006b). Although not an appetitive task, similar results have been noted for inhibition of memory formation of inhibitory avoidance via post-training intra-amygdala infusions of NMDA receptor antagonists (Jerusalinsky, Ferreira, Walz, Da Silva, Bianchin, Ruschel, Zanatta, Medina, and Izquierdo, 1992; Liang et al., 1994). These effects were dose- and time-dependent, in that AP-5 administered ≥ 90 min after training had no effect of memory retention. Further support for the role of the BLA in memory consolidation comes from studies examining the administration of protein synthesis inhibitors. In one such study, intra-BLA administration of protein synthesis (anisomycin) or protein kinase A (Rp-cAMPS) inhibitors immediately after training led to a significant dose-dependent reduction in Pavlovian fear conditioning (Schafe and LeDoux, 2000), and these effects were time-dependent, since administration 6 h after conditioning had no effects.

While we anticipated that NMDA receptors would be important in cocaine-cue associative learning, the differences in the dose of AP-5 required to disrupt acquisition vs. consolidation were unexpected (i.e., a higher dose of AP-5 was required when administered prior to CC to achieve a significant reduction in drug-seeking during cue-induced reinstatement). It is possible that this difference may have resulted from changes in neural activity that occurred in the presence of cocaine during the acquisition phase, specifically dopamine-mediated mechanisms in associative learning via cocaine-induced elevated DA levels. Previous research has indicated a significant increase in extracellular DA in the amygdala, including the lateral and basal nuclei, during exposure to psychostimulants (Harmer, Hitchcott, Morutto, and Phillips, 1997; Young and Rees, 1998). This enhancement in DA activity during the time of CC could have potentiated drug-CS associative learning, even in the presence of AP-5. In support of this possibility, we have previously found a potentiation of cue-induced reinstatement following intra-BLA infusions of d-amphetamine (Ledford, Fuchs, and See, 2003). Furthermore, we have shown that either a dopamine D1 receptor antagonist (SCH23390) or a dopamine D2/3 receptor antagonist (raclopride) administered prior to the CC session attenuated the later expression of conditioned-cued reinstatement (Berglind et al., 2006). It is also possible that the higher dose of AP-5 was effective when given immediately prior to the CC session in that its effects carried over to the consolidation phase. That is, while the 3 μg dose of AP-5 may have been metabolized and/or removed over the course of the 1-h CC session, the 10 μg dose may have remained active after the conclusion of the session, thus inhibiting the consolidation of drug-CS associative learning. Alternatively, the higher dose of AP-5 could have had non-specific effects independent of learning. Indeed, higher doses of NMDA antagonists have been known to produce sensorial disturbances (Tan, Kirk, Abraham, and McNaughton, 1989; Tang and Ho, 1988). Similar to the current results, intra-accumbens infusions of AP-5 in a passive avoidance learning task produced only a modest dose-dependent effect when given prior to training, while the same doses produced greater effects when administered at the time of consolidation (De Leonibus, Costantini, Castellano, Ferretti, Oliverio, and Mele, 2003). In a morphine conditioned place preference paradigm, administration of a protein synthesis inhibitor (anisomycin) that was effective at preventing memory consolidation had no effect when given prior to training (Robinson and Franklin, 2007), suggesting that different processes may be involved in memory acquisition versus consolidation. Future studies should investigate the roles of different glutamate receptor subtypes during these various stages of drug-CS associative learning.

Based on previous amygdalar learning paradigms, it is likely that AP-5 disrupts cocaine-cue associative learning by attenuation of NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation (LTP). This hypothesis is supported by studies in which intra-BLA infusions of AP-5 impaired the acquisition, but not the expression, of approach behaviors to an appetitive CS (Burns et al., 1994) and appetitive instrumental behaviors (Baldwin et al., 2000). LTP is a neuronal model of learning that has been demonstrated to occur in vitro (Chapman and Bellavance, 1992; Chapman, Kairiss, Keenan, and Brown, 1990) and in vivo (Clugnet and LeDoux, 1990; Maren and Fanselow, 1995) in the BLA, and appears to require the activation of NMDA receptors (Gean, Chang, Huang, Lin, and Way, 1993; Huang and Kandel, 1998; Maren and Fanselow, 1995), although there are some exceptions (Chapman and Bellavance, 1992).

Consistent with the effect we previously found with tetrodotoxin (Fuchs et al., 2006b), intra-BLA infusions of AP-5 administered immediately after the CS reinstatement tests inhibited subsequent conditioned-cued extinction learning, presumably by preventing the consolidation of new information about the changed value of the CS (i.e., CS-no drug associations). These effects are similar to anisomycin-induced prevention of incentive learning in the amygdala related to the reduction of a food reward when given immediately after a series of devaluation sessions (Wang, Ostlund, Nader, and Balleine, 2005), and the prevention of extinction of cocaine-seeking behavior in a context-induced reinstatement model of relapse (Fuchs, Eaddy, Su, and Bell, 2006a). Contrary to short-term memories, the consolidation of long-term extinction memories appears to be an NMDA receptor-mediated event (Santini, Muller, and Quirk, 2001), as supported by a series of studies using fear-conditioning paradigms in which intra-BLA NMDA receptor blockade produced long-term deficits in extinction of conditioned-freezing (Lee and Kim, 1998; Lee et al., 2006) and fear-potentiated startle (Falls, Miserendino, and Davis, 1992) behaviors. Moreover, overexpression of an NMDA receptor subunit (NR2B) has been found to enhance extinction learning in mice (Tang, Shimizu, Dube, Rampon, Kerchner, Zhuo, Liu, and Tsien, 1999), an effect further validated by studies that have shown facilitation of extinction learning in animals that received systemic (Botreau, Paolone, and Stewart, 2006; Lee et al., 2006) or intra-BLA infusions (Lee et al., 2006) of the partial NMDA receptor agonist, d-cycloserine.

According to the “trace dominance” hypothesis (Dudai, 2004; Nader, 2003), re-exposure to the CS alone can lead to 2 opposing processes: the “reconsolidation” of the original CS-US memory (i.e., reminder learning) and the consolidation of CS-no US memories (i.e., extinction learning). These processes are thought to occur simultaneously (Debiec, LeDoux, and Nader, 2002; Eisenberg, Kobilo, Berman, and Dudai, 2003); however, which of the two processes dominates depends on a number of factors. When exposure is limited, the CS produces internal reinforcement by it's own conditioned reinforcing properties and “reconsolidation” of the original CS-US memory is thought to dominate (Eisenhardt and Menzel, 2007). However, continuous exposure to the CS in the absence of external reinforcement (i.e., the US) results in extinction learning becoming stronger, while the reminder memory becomes simultaneously weakened. Given this proposed interaction, it can be hypothesized that the administration of amnesic agents at different time points would lead to different outcomes, such that the inhibition of “reminder learning” would result in the CR decreasing, whereas the inhibition of “extinction learning” would result in the opposite (i.e., the CR is maintained). In support of this theory, intra-BLA infusions of antisense oligodeoxynucleotides that target the protein Zif268 following brief re-exposure (15 min) to a cocaine-paired CS prevented the ability of the CS to facilitate the acquisition of new cocaine-seeking behavior (Lee, Di Ciano, Thomas, and Everitt, 2005), consistent with an inhibition of reconsolidation. In a direct temporal comparison, intra-BLA infusions of anisomycin immediately after 15 min of re-exposure to a previously drug-paired context attenuated context-induced subsequent reinstatement of cocaine-seeking, whereas the same treatment after 120 min of re-exposure led to the opposite effect (i.e., continued reinstatement over subsequent tests), indicating time-dependent inhibition of reconsolidation or consolidation of extinction learning, respectively (Fuchs et al., 2006a). Thus, future studies should examine the temporal role of the BLA in the consolidation and reconsolidation of drug-stimulus associative learning, as well as any putative interactions among these competing processes.

Along with previous studies, the current results suggest a fundamental role of the amygdala in a number of stages of drug-cue associative learning. While it is impossible to intervene in the initial acquisition and consolidation of the drug-cue associations that play a critical role in both ongoing drug-seeking behavior and relapse (Gawin, 1991), various possibilities exist for the utilization of drugs that either inhibit the reconsolidation of drug-CS associations, or facilitate the consolidation of extinction learning (i.e., CS-no drug associations). While extinction therapy has been shown to attenuate conditioned responses to previously drug-paired stimuli (O'Brien, Childress, McLellan, and Ehrman, 1992), its effectiveness to date appears fairly limited. Thus, the administration of adjunctive pharmacotherapies that modulate glutamate receptors (e.g., d-cycloserine), in combination with behaviorally-based therapies, may prove especially beneficial for reducing the impact of drug-paired environmental stimuli to precipitate drug craving and relapse.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alisha Henderson for excellent technical assistance. This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants DA010462 (RES) and DA07288 (MWF), and NIH grant C06 RR015455.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baldwin AE, Holahan MR, Sadeghian K, Kelley AE. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-dependent plasticity within a distributed corticostriatal network mediates appetitive instrumental learning. Behav Neurosci. 2000;114:84–98. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglind WJ, Case JM, Parker MP, Fuchs RA, See RE. Dopamine D1 or D2 receptor antagonism within the basolateral amygdala differentially alters the acquisition of cocaine-cue associations necessary for cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. Neuroscience. 2006;137:699–706. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonson KR, Grant SJ, Contoreggi CS, Links JM, Metcalfe J, Weyl HL, Kurian V, Ernst M, London ED. Neural systems and cue-induced cocaine craving. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:376–386. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botreau F, Paolone G, Stewart J. d-Cycloserine facilitates extinction of a cocaine-induced conditioned place preference. Behav Brain Res. 2006;172:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiter HC, Gollub RL, Weisskoff RM, Kennedy DN, Makris N, Berke JD, Goodman JM, Kantor HL, Gastfriend DR, Riorden JP, Mathew RT, Rosen BR, Hyman SE. Acute effects of cocaine on human brain activity and emotion. Neuron. 1997;19:591–611. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns LH, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Intra-amygdala infusion of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist AP5 impairs acquisition but not performance of discriminated approach to an appetitive CS. Behav Neural Biol. 1994;61:242–250. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(05)80007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cador M, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Involvement of the amygdala in stimulus-reward associations: interaction with the ventral striatum. Neuroscience. 1989;30:77–86. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman PF, Bellavance LL. Induction of long-term potentiation in the basolateral amygdala does not depend on NMDA receptor activation. Synapse. 1992;11:310–318. doi: 10.1002/syn.890110406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman PF, Kairiss EW, Keenan CL, Brown TH. Long-term synaptic potentiation in the amygdala. Synapse. 1990;6:271–278. doi: 10.1002/syn.890060306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress AR, Hole AV, Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ, McLellan AT, O'Brien CP. Cue reactivity and cue reactivity interventions in drug dependence. NIDA Res Monogr. 1993;137:73–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress AR, Mozley PD, McElgin W, Fitzgerald J, Reivich M, O'Brien CP. Limbic activation during cue-induced cocaine craving. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:11–18. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clugnet MC, LeDoux JE. Synaptic plasticity in fear conditioning circuits: induction of LTP in the lateral nucleus of the amygdala by stimulation of the medial geniculate body. J Neurosci. 1990;10:2818–2824. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-08-02818.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis CA, O'Brien CP. Cocaine dependence: a disease of the brain's reward centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;21:111–117. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Rainnie D, Cassell M. Neurotransmission in the rat amygdala related to fear and anxiety. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:208–214. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leonibus E, Costantini VJ, Castellano C, Ferretti V, Oliverio A, Mele A. Distinct roles of the different ionotropic glutamate receptors within the nucleus accumbens in passive-avoidance learning and memory in mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:2365–2373. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Stewart J. Reinstatement of cocaine-reinforced responding in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1981;75:134–143. doi: 10.1007/BF00432175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debiec J, LeDoux JE, Nader K. Cellular and systems reconsolidation in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2002;36:527–538. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudai Y. The neurobiology of consolidations, or, how stable is the engram? Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:51–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ, Childress AR, O'Brien CP. Conditioned responses to cocaine-related stimuli in cocaine abuse patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;107:523–529. doi: 10.1007/BF02245266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg M, Kobilo T, Berman DE, Dudai Y. Stability of retrieved memory: inverse correlation with trace dominance. Science. 2003;301:1102–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1086881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt D, Menzel R. Extinction learning, reconsolidation and the internal reinforcement hypothesis. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;87:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Parkinson JA, Olmstead MC, Arroyo M, Robledo P, Robbins TW. Associative processes in addiction and reward. The role of amygdala- ventral striatal subsystems. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:412–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falls WA, Miserendino MJ, Davis M. Extinction of fear-potentiated startle: blockade by infusion of an NMDA antagonist into the amygdala. J Neurosci. 1992;12:854–863. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-00854.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, Altar CA, See RE. Aripiprazole blocks reinstatement of cocaine seeking in an animal model of relapse. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:582–590. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry B, Di Scala G. Basolateral amygdala NMDA receptors are selectively involved in the acquisition of taste-potentiated odor aversion in the rat. Behav Neurosci. 2000;114:1005–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs R, Eaddy J, Su ZI, Bell G. Basolateral amygdala involvement in consolidation and reconsolidation processes relevant to drug context-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. Nueropsychopharmacology. 2006a;31:S202. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Evans KA, Parker MP, See RE. Differential involvement of orbitofrontal cortex subregions in conditioned cue-induced and cocaine-primed reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6600–6610. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1924-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Feltenstein MW, See RE. The role of the basolateral amygdala in stimulus-reward memory and extinction memory consolidation and in subsequent conditioned-cued reinstatement of cocaine seeking. Eur J Neurosci. 2006b;23:2809–2813. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawin FH. Cocaine addiction: psychology and neurophysiology. Science. 1991;251:1580–1586. doi: 10.1126/science.2011738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gean PW, Chang FC, Huang CC, Lin JH, Way LJ. Long-term enhancement of EPSP and NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission in the amygdala. Brain Res Bull. 1993;31:7–11. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90003-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosens KA, Maren S. Pretraining NMDA receptor blockade in the basolateral complex, but not the central nucleus, of the amygdala prevents savings of conditional fear. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:738–750. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.4.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant S, London ED, Newlin DB, Villemagne VL, Liu X, Contoreggi C, Phillips RL, Kimes AS, Margolin A. Activation of memory circuits during cue-elicited cocaine craving. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:12040–12045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm JW, See RE. Dissociation of primary and secondary reward-relevant limbic nuclei in an animal model of relapse. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:473–479. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer CJ, Hitchcott PK, Morutto SL, Phillips GD. Repeated damphetamine enhances stimulated mesoamygdaloid dopamine transmission. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;132:247–254. doi: 10.1007/s002130050342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield T, Gallagher M. Taste-potentiated odor conditioning: impairment produced by infusion of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist into basolateral amygdala. Behav Neurosci. 1995;109:663–668. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.109.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield T, Han JS, Conley M, Gallagher M, Holland P. Neurotoxic lesions of basolateral, but not central, amygdala interfere with Pavlovian second-order conditioning and reinforcer devaluation effects. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5256–5265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05256.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder C. Novel pharmacotherapeutic targets for the management of drug addiction. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;526:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Kandel ER. Postsynaptic induction and PKA-dependent expression of LTP in the lateral amygdala. Neuron. 1998;21:169–178. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerusalinsky D, Ferreira MB, Walz R, Da Silva RC, Bianchin M, Ruschel AC, Zanatta MS, Medina JH, Izquierdo I. Amnesia by post-training infusion of glutamate receptor antagonists into the amygdala, hippocampus, and entorhinal cortex. Behav Neural Biol. 1992;58:76–80. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(92)90982-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantak KM, Black Y, Valencia E, Green-Jordan K, Eichenbaum HB. Dissociable effects of lidocaine inactivation of the rostral and caudal basolateral amygdala on the maintenance and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1126–1136. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-01126.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilts CD, Gross RE, Ely TD, Drexler KP. The neural correlates of cue-induced craving in cocaine-dependent women. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:233–241. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilts CD, Schweitzer JB, Quinn CK, Gross RE, Faber TL, Muhammad F, Ely TD, Hoffman JM, Drexler KP. Neural activity related to drug craving in cocaine addiction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:334–341. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruzich PJ, Congleton KM, See RE. Conditioned reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior with a discrete compound stimulus classically conditioned with intravenous cocaine. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:1086–1092. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.115.5.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruzich PJ, See RE. Differential contributions of the basolateral and central amygdala in the acquisition and expression of conditioned relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledford CC, Fuchs RA, See RE. Potentiated reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior following D-amphetamine infusion into the basolateral amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1721–1729. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Kim JJ. Amygdalar NMDA receptors are critical for new fear learning in previously fear-conditioned rats. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8444–8454. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08444.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Di Ciano P, Thomas KL, Everitt BJ. Disrupting reconsolidation of drug memories reduces cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuron. 2005;47:795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Milton AL, Everitt BJ. Reconsolidation and extinction of conditioned fear: inhibition and potentiation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10051–10056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2466-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang KC, Hon W, Davis M. Pre- and posttraining infusion of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists into the amygdala impair memory in an inhibitory avoidance task. Behav Neurosci. 1994;108:241–253. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S, Aharonov G, Stote DL, Fanselow MS. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in the basolateral amygdala are required for both acquisition and expression of conditional fear in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:1365–1374. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.6.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S, Fanselow MS. Synaptic plasticity in the basolateral amygdala induced by hippocampal formation stimulation in vivo. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7548–7564. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07548.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin J, See RE. Selective inactivation of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and the basolateral amygdala attenuates conditioned-cued reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meil WM, See RE. Conditioned cued recovery of responding following prolonged withdrawal from self-administered cocaine in rats: an animal model of relapse. Behav Pharmacol. 1996;7:754–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meil WM, See RE. Lesions of the basolateral amygdala abolish the ability of drug associated cues to reinstate responding during withdrawal from self-administered cocaine. Behav Brain Res. 1997;87:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)02270-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan DT, Cotman CW. Distribution of N-methyl-D-aspartate-sensitive L-[3H]glutamate-binding sites in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1985;5:2909–2919. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-11-02909.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader K. Memory traces unbound. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:65–72. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(02)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisewander JL, Baker DA, Fuchs RA, Tran-Nguyen LT, Palmer A, Marshall JF. Fos protein expression and cocaine-seeking behavior in rats after exposure to a cocaine self-administration environment. J Neurosci. 2000;20:798–805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00798.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien CP, Childress AR, McLellan AT, Ehrman R. Classical conditioning in drug-dependent humans. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;654:400–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb25984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Compact 3. Academic Press; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MJ, Franklin KB. Effects of anisomycin on consolidation and reconsolidation of a morphine-conditioned place preference. Behav Brain Res. 2007;178:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini E, Muller RU, Quirk GJ. Consolidation of extinction learning involves transfer from NMDA-independent to NMDA-dependent memory. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9009–9017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-09009.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafe GE, LeDoux JE. Memory consolidation of auditory pavlovian fear conditioning requires protein synthesis and protein kinase A in the amygdala. J Neurosci. 2000;20:RC96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-j0003.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See RE. Neural substrates of cocaine-cue associations that trigger relapse. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;526:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See RE, Kruzich PJ, Grimm JW. Dopamine, but not glutamate, receptor blockade in the basolateral amygdala attenuates conditioned reward in a rat model of relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;154:301–310. doi: 10.1007/s002130000636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See RE, McLaughlin J, Fuchs RA. Muscarinic receptor antagonism in the basolateral amygdala blocks acquisition of cocaine-stimulus association in a model of relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuroscience. 2003;117:477–483. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00665-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Shalev U, Lu L, De Wit H, Stewart J. The reinstatement model of drug relapse: history, methodology and major findings. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168:3–20. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S, Kirk RC, Abraham WC, McNaughton N. Effects of the NMDA antagonists CPP and MK-801 on delayed conditional discrimination. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1989;98:556–560. doi: 10.1007/BF00441959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang AH, Ho PM. Both competitive and non-competitive antagonists of N-methyl-D-aspartic acid disrupt brightness discrimination in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;151:143–146. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90705-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YP, Shimizu E, Dube GR, Rampon C, Kerchner GA, Zhuo M, Liu G, Tsien JZ. Genetic enhancement of learning and memory in mice. Nature. 1999;401:63–69. doi: 10.1038/43432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, Childress AR, Jayne M, Ma Y, Wong C. Cocaine cues and dopamine in dorsal striatum: mechanism of craving in cocaine addiction. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6583–6588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1544-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner FA, Anthony JC. From first drug use to drug dependence; developmental periods of risk for dependence upon marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:479–488. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DL, Paschall GY, Davis M. Glutamate receptor antagonist infusions into the basolateral and medial amygdala reveal differential contributions to olfactory vs. context fear conditioning and expression. Learn Mem. 2005;12:120–129. doi: 10.1101/lm.87105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace BC. Psychological and environmental determinants of relapse in crack cocaine smokers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1989;6:95–106. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(89)90036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SH, Ostlund SB, Nader K, Balleine BW. Consolidation and reconsolidation of incentive learning in the amygdala. J Neurosci. 2005;25:830–835. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4716-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F, Maldonado-Vlaar CS, Parsons LH, Kerr TM, Smith DL, Ben-Shahar O. Control of cocaine-seeking behavior by drug-associated stimuli in rats: effects on recovery of extinguished operant-responding and extracellular dopamine levels in amygdala and nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4321–4326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitelaw RB, Markou A, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Excitotoxic lesions of the basolateral amygdala impair the acquisition of cocaine-seeking behaviour under a second-order schedule of reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;127:213–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, Rees KR. Dopamine release in the amygdaloid complex of the rat, studied by brain microdialysis. Neurosci Lett. 1998;249:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00390-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]