Abstract

Repression is associated in the literature with terms such as non-expression, emotional control, rationality, anti-emotionality, defensiveness and restraint. Whether these terms are synonymous with repression, indicate a variation, or are essentially different from repression is uncertain. To clarify this obscured view on repression, this paper indicates the similarities and differences between these concepts. Repression is the general term that is used to describe the tendency to inhibit the experience and the expression of negative feelings or unpleasant cognitions in order to prevent one’s positive self-image from being threatened (‘repressive coping style’). The terms self-deception versus other-deception, and socially related versus personally related repression refer to what is considered to be different aspects of repression. Defensiveness is a broader concept that includes both anxious defensiveness and repression; the essential difference is whether negative emotions are reported or not. Concepts that are sometimes associated with repression, but which are conceptually different, are also discussed in this paper: The act of suppression, ‘repressed memories,’ habitual suppression, concealment, type C coping pattern, type D personality, denial, alexithymia and blunting. Consequences for research: (1) When summarizing findings reported in the literature, it is essential to determine which concepts the findings represent. This is rarely made explicit, and failure to do so may lead to drawing the wrong conclusions (2) It is advisable to use scales based on different aspects of repression (3) Whether empirical findings substantiate the similarities and differences between concepts described in this paper will need to be shown.

Keywords: Repression, Defensiveness, Emotional control, Restraint, Self-deception, Type C, Denial, Alexithymia

Introduction

People differ in their tendency to openly show, or to hide their negative emotions. This is an important topic in behavioral medicine, since studies have shown that repression is a potential health risk factor for disorders as diverse as chronic pain (Beutler et al. 1986) and cancer (Jensen 1987; Weihs et al. 2000). Another reason why repression may be considered a relevant topic for research in this field is that the tendency to avoid expressing negative emotions (also labeled ‘repressive coping style’) is known to distort the assessment of a patient’s distress. As a result, this tendency to repress negative emotions may lead to making false conclusions. For instance, if patients report levels of distress similar to healthy individuals but show more repressive tendencies, they may in fact be more distressed. This repressive tendency may even influence the reporting of somatic symptoms and quality of life (Koller et al. 1999).

The possible influence of repression on disease development, health behavior and symptom reporting has been investigated in many studies. Summarizing the findings proves problematic, however, as authors use different labels for ‘repression-like’ concepts, such as repression, suppression, non-expression of negative emotions, emotional control, emotional inhibition, rationality, anti-emotionality, type C response style, defensiveness, restraint, concealment, type D personality, denial, alexithymia and blunting. It is unclear whether this array of terms actually refers to the same concept or altogether different concepts. For instance, is forgetting details of traumatic events (e.g., sexual abuse or war experiences) comparable to not wanting to show one’s emotions because of one’s preference to rationalize? Is the tendency to minimize one’s problems and to emphasize the positive aspects of experiences comparable to non-expression of negative emotions because one is afraid of personal confrontation? And yet in all these instances, the term repression is used.

The meanings of the various terms used in this field are defined below and an attempt is made to analyze their relationships on a conceptual level. This treatise does not discuss theories of repression and related constructs, but concerns the meaning of concepts. In our view, confusion exists more on the level of concepts than on the level of theories, and these theories are not very helpful in clarifying the conceptual confusion that exists. For instance, there is no theory that brings to notice that repression and concealment—whereas the literal meaning of these words may suggest overlap—refer to fundamentally different concepts. Nor is there any theory that alerts against the special use in some Behavioral Medicine texts of the term ‘denial’ in the sense of minimizing the seriousness of a disease and not as denial of negative emotional states in general (Brown et al. 2000; Butow et al. 1999, 2000; Greer et al. 1979). It is important to add here, that several terms in this field have been introduced not on the basis of theory, but during the process of developing a measurement method.

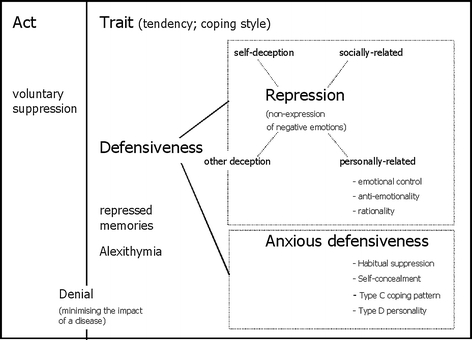

We make a distinction between those concepts that in our view are related to repression, and other concepts that are sometimes defined as similar to or related to repression, but are clearly different. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual network.

Fig. 1.

A conceptual diagram indicating which concepts fall under the headings of repression and anxious defensiveness, respectively, and which concepts are sometimes associated with, but theoretically different from defensiveness (voluntary suppression, repressed memories, denial and alexithymia)

Repression

Repression is the general term that is used to describe the tendency to inhibit the experience and the expression of negative feelings or unpleasant cognitions in order to prevent one’s positive self-image from being threatened. A typical example of a person with repressive tendencies would be a sociable and cheerful man who rarely complains about any misfortune including disease, and whose self-image is one of a positive-minded person who is in control of his life. When he encounters someone who discusses an emotional problem, he is inclined to quickly change the subject in an attempt to avoid entering a world of anxiety, sadness or worry, which would imply that he has lost control.

Other authors have presented comparable definitions, such as “Individuals who avoid focusing on ego-threatening material are termed repressors” (Ashley and Holtgraves 2003), or “repression can be defined as the avoidance of threatening information” (Baumeister and Cairns 1992). The motive of “preventing one’s positive self-image from being threatened” is added in order to exclude some forms of non-expression, namely those due to shyness, social phobia and introversion. Shy or social-phobic people fear social situations, which inhibits their emotional expression, whereas repressive people do not fear or avoid social situations. Another difference is that shyness, social phobia and introversion refer to non-expression of both negative and positive feelings, whereas repression refers only to non-expression of negative feelings.

We use the term ‘non-expression of negative emotions’ here as a synonym for repression. This term suggests perhaps a focus on expressive behavior only, but it actually refers to the inhibition of both emotional experiences and behaviors. An explicit restriction is made to negative emotions, rather than emotions in general. This asymmetry, implied in the definition of repression, is mirrored by empirical findings. A repressive tendency appears to be related to downplaying negative aspects rather than to overstating positive aspects of a person (Myers and Brewin 1996), and to a memory deficit for real life events associated with negative emotions but not for events associated with positive emotions (Davis 1987).

There is no reason to label repression as either positive or negative on a phenomenological level. Repressive people will generally not bother other people with their problems and may even facilitate social situations by their positive attitude (Furnham et al. 2003). Conversely, this coping style may impoverish intimate social interactions and may in the long run have a negative impact on the person’s own functioning, due to a lack of insight into their own psychological functioning, a decrease in the variety of their coping repertoire and overlooking signals that lead to seeking medical help in time. In the long term repression may have negative somatic consequences, including an increased risk of various disorders.

Below is first discussed a proposal by Weinberger to make a distinction between repression and anxious defensiveness (Weinberger et al. 1979; Weinberger 1990; Weinberger and Schwartz 1990). This distinction is useful for placing repression-like concepts under one of these two headings.

Defensiveness

Whereas most elements in this discussion can be approached on a merely conceptual level, the discussion of the concept of Defensiveness needs to be introduced by mentioning empirical findings. Weinberger (1990) makes a distinction between two types of defensiveness: He defines repression as scoring high on defensiveness but low on anxiety, and anxious defensiveness as scoring high on both defensiveness and distress self-report scales.1 In fact, Weinberger formed six groups, based on a tripartition of restraint scores and a dipartition of distress scores, but the remaining four groups are not relevant to this discussion. In an earlier publication he describes a more familiar division of defensiveness types based on a dipartition of social desirability scores and anxiety scores, which is comparable to his more recent division (Weinberger et al. 1979). The two groups appeared to be different on a number of personality variables. Compared to the other groups, the anxious defensive group scored low with respect to assertiveness, ability to express themselves in close relationships, sensitivity to their own needs and feelings, self-esteem and self-control. They also scored high on avoidant personality (shyness), dependency (emotional reliance on others and approval dependence), obsessive worrying, and (minor) physical illnesses. The repressive group, on the other hand, was characterized by high scores for intimacy, self-esteem, self-control (tendency to use self-management techniques), defensiveness and alexithymia2, while low on avoidant personality. These differences in a broad spectrum of personality traits indicate that the division into the two defensiveness groups is more than the product of an arithmetic procedure; it refers to a constellation of essential individual differences (Weinberger and Schwartz 1990).

Defensiveness, therefore, covers a broader category than repression. Defensiveness concerns different strategies to protect oneself against being hurt psychologically. One strategy is to behave—more or less anxiously—in a socially acceptable way, to be nice in order not to get hurt, and to avoid social confrontations. Another strategy is to inhibit thoughts about negative aspects of oneself, and to consider oneself as the social person one would rather be. The first condition, anxious defensiveness, includes the awareness of negative emotions, whereas the second condition, repression, denies these emotions.

Weinberger’s division into two forms of defensiveness is highly useful. If high levels of anxiety or other forms of distress are implied in the definition of a repression-like concept, one should place this concept under the heading of anxious defensiveness, rather than under the heading repression. On an empirical level, a low level of distress reporting in repression would be expected (negative relationship between repression and distress), and a relatively high level in anxious defensiveness (positive relation).

(Un)consciousness

Repression is a tendency that a person may be (partly) aware of, which in psychodynamic theories is referred to as suppression, or unaware of, referred to as repression in these theories. However, (un)consciousness is often not explicitly included in the definition of repression as a distinctive characteristic. To give some citations: “Repression can be defined as the avoidance of threatening information” (Baumeister and Cairns 1992, p. 853). “Repressors are individuals who habitually and efficiently control their emotions” (Boden and Dale 2001, p. 122). Some authors—on the contrary—stress the role of the unconscious: “Repressive-defensiveness is characterized by a non-conscious avoidance of threatening information” (King et al. 1992, p. 87). Repressive-defensiveness is defined here according to Weinberger’s operational definition of repression (Weinberger et al. 1979; see above). Quite confusing is that other authors, using a different term namely repressive coping but referring to the same operational definition of Weinberger, claim the opposite: “Repressive coping is thought to modulate the conscious experience of negative affect following the appraisal of threat” (Newton and Contrada 1992, p. 160). Most contemporary authors describe repression in terms of active cognitive processes, such as selective inattention and motivated forgetting rather than in terms of an unconscious defense mechanisms (Baumeister and Cairns 1992; Newton and Contrada 1992; Mendolia et al. 1996). The most explicit view on this comes from Erdelyi (1993, 2001), who states that empirical findings do not support any distinction between conscious and unconscious forms of emotional inhibition. He also uses an historical argument. Whereas many authors referred to Freud when discussing the difference between repression and suppression, this is—in Erdeleyi’s view—historically unwarranted, given that Freud used these terms interchangeably. The notion that repression must be unconscious is not Sigmund Freud’s, but his daughter’s, Anna Freud (1946).

If any distinction is made between suppression and repression, the focus is usually placed on processes, i.e. on time-limited cognitive acts. The distinction between conscious and unconscious forms of inhibition does seem possible and it is perhaps useful when applying it to acts, but this distinction is more difficult to apply to traits. The discussion below is about repression as a trait (‘repressiveness’). One may on occasion be aware of one’s tendency to inhibit the experience and expression of negative feelings, but most of the time be vaguely aware, and more often totally unaware of them.

Empirical findings indicate that repressors are often unaware, or at least not fully aware of their emotional avoidance style. As indicated below, repressors genuinely perceive themselves as being low in anxiety and are primarily self-deceivers. Another indication for the (mainly) unconscious character of repression is the repressor’s decreased ability to recall personal experiences associated with a negative affect. When memories are recalled by repressors, thus having become conscious, they are not processed more slowly than by the non-repressors (Davis 1987).

Self-deception and Other-deception

Expressing negative emotions may be deliberately avoided as part of the tendency to make a favorable impression on other people. This tendency is called impression management or, originally, other-deception. It is distinguishable from self-deception, in which case the person actually believes his or her positive self-reports (Paulhus 1984; Rogers and Kristjanson 2002).

Impression management is modestly and negatively related to reports of negative emotions and somatic symptoms, while a self-deceptive response style reduces symptom reporting above the effects of deliberate impression management (Linden et al. 1986). Given that underreporting negative emotions is the hallmark of repression, these findings seem to indicate that self-deception is closer to repression than impression management. Another characteristic of repression is a deficiency in the memory for emotional events (Furnham et al. 2003; Davis 1987). This deficiency appeared to be related to self-deception, but not to impression management (Ashley and Holtgraves 2003).

Two studies found that repressors scored high on both other-deception and self-deception questionnaires (Derakshan and Eysenck 1999; Furnham et al. 2002). The study of Derakshan and Eysenck (1999) also showed that repressors are more self-deceivers than other-deceivers. This was demonstrated with the so-called ‘bogus pipeline’ method, where participants are connected via electrodes to a piece of apparatus resembling a lie detector, which could allegedly detect whether they are telling the truth. Compared to a control condition, people are generally more willing to report truthfully about their emotional states when subjected to the bogus line condition, even if this report is seen as socially undesirable or embarrassing for that person. Repressors generally did not show any difference in anxiety scores between both conditions. This finding suggests that repressors genuinely perceive themselves as being low in anxiety. They are mainly self-deceivers, though the questionnaire data indicated that they also showed some tendency to present themselves deliberately in a socially desirable light. In another experiment, Baumeister and Cairns (1992) showed that repressors who privately received threatening feedback spent the least amount of time reading it, whereas repressors who received the same feedback publicly spent considerably more time reading it. Non-repressors were unaffected by the favorability of the evaluation (threatening or not) or the private versus public nature of the situation. These findings suggest that repressors abandon self-deceptive strategies in favor of impression management strategies in an attempt to invalidate the socially undesirable information about their personality.

Doubts have arisen about the validity of self-deception (SD) and other-deception (OD) scales, including the widely used Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding (BIDR) of Paulhus (1984). Studies have shown that the scores to SD and OD scales can be influenced by instructions (Stober et al. 2002; Pauls and Crost 2004), such as a fake good instruction (e.g. “Present yourself as much as possible in a favorable light”), a fake being competent instruction (e.g. “Present yourself as much as possible as being competent and self-confident”), or a fake social harmony instruction (e.g. “Present yourself as much as possible in an agreeable and conscientious light”). The SD and OD scores changed differently, dependent on the type of instruction. For instance, SD scores were most sensitive to the competence instruction and OD scores were most sensitive to the social harmony instruction (Pauls and Crost 2004). SD and OD were measured in this study with the widely used Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding. The authors of this study argue that this questionnaire does not so much measure SD and OD, as is generally believed, but more so overconfidence versus need for social harmony. This may imply that the question whether repression is predominantly associated with self-deception or other-deception cannot be answered with so-called SD and OD scales, but only with experimental designs such as applied in the studies of Derakshan and Eysenck (1999) and Baumeister and Cairns (1992).

What is the precise relationship between these two concepts and repression? The character of self-deception, i.e., believing one’s positive self-report, is completely compatible with the definition of repression. There is, however, no complete overlap between repression and impression management. An extreme form of impression management would be consciously trying to project a positive image towards others while being fully aware of one’s negative feelings and negative cognitions. This condition of other-deception without self-deception is not compatible with the description of repression. Because of this conceivable exception, other-deception is depicted in Fig. 1 as only partly overlapping with repression.

Different Aspects of Repression

Certain explanations of repression seem to emphasize the social aspect, whereas other explanations do not describe the repressive tendency as specifically socially related. For instance, Weinberger and Schwarz, who used the term ‘self-restraint’, state that it concerns ‘domains related to socialization and self-control and refers to repression of egoistic desires in the interest of long-term goals and relations with others’. The term ‘self-restraint’ also encompasses ‘tendencies to inhibit aggressive behavior, to exercise impulse control, to act responsibly, and to be considerate of others’ (Weinberger and Schwartz 1990, p. 382). To label such tendencies, the term ‘socially related repression’ would therefore seem appropriate. These tendencies may be part of the broader tendency to behave in a socially acceptable way, which should not be conceived as simply the need to follow external norms, but reflect a self-concept that depends on the approval of other people.

We suggest using the label ‘personally related repression’ for a second aspect of repression, which is not primarily socially related and may be defined as the general tendency to inhibit one’s expression of anxiety, depression, worry and anger, and not to let oneself be influenced by these negative feelings. This heading subsumes several concepts. Watson and Greer (1983) use the term emotional control and describe it as ‘the extent to which individuals report controlling their reactions when a particular emotion is experienced’, especially anger, anxiety and depressed mood. This description does not specifically suggest social determination. Rationality is another example and is described by Spielberger (1988) as ‘the extent to which an individual uses reason and logic as a general approach to coping with the environment’.

Empirical support for our proposed division was found in a study that applied a secondary factor analysis to investigate the interrelationships between various subscales of two repression questionnaires and three distress questionnaires (Giese-Davis and Spiegel 2001). The scales applied in this study were the three subscales of the Courtauld Emotional Control Scale (CECS) used to measure emotional control, the five subscales of the Weinberger Attitude Inventory (WAI), used to measure self restraint, and three distress questionnaires (POMS, CES-D and IES; four subscales in total). There is no reference to social situations in the items included in the CECS (Watson and Greer 1983). An example item is “When I feel afraid or worried, I smother my feelings”. Most of the items of in the WAI subscales (D. A. Weinberger, unpublished ) refer to social situations, such as the item “I think about other people’s feelings before I do something they might not like”. One would expect personally related repression scales (CECS) to load on one dimension and scales assessing socially related repression (WAI) on a second dimension (and the distress scales on a third dimension). The factor analysis yielded a four-factor solution, including (1) subscales of the CECS (2) WAI restraint scales (3) WAI defensiveness scales and (4) the distress scales. We cannot explain why the WAI repression scales loaded on two different factors. However, the finding that the CECS scales clustered in one factor and the WAI repression scales in two other factors, could be seen as support for our division into personally related and socially related repression.

Concepts Different from Repression

Concepts that are in our view different from repression are: the act of emotional suppression, repressed memories, habitual suppression, concealment, type C coping pattern, type D personality, denial, alexithymia and blunting. The first concept refers to an ‘act,’ whereas repression is discussed in this paper as a tendency or coping style. Four of these concepts—habitual suppression, concealment, type C coping style and type D personality should, in our view, be interpreted as types of anxious defensiveness rather than forms of repression. Our motive for discussing these ‘non-repression’ concepts is that the literature may suggest that these concepts are related to repression.

The Act of Voluntary Suppression of Emotionally Charged Material

In an experimental context people can be asked to refrain from showing emotional reactions, or to try not to think about an emotional condition. Suppression of emotional behavior or thoughts can also occur spontaneously in everyday life. Given that such acts can be performed incidentally, both by people high or low in repression, the act should be distinguished from the habitual response style. It cannot simply be assumed that the consequences of the act of emotional suppression are similar to the psychological and somatic concomitants of being an habitual repressor. For instance, in the long term emotional disclosure leads to a decrease in reported psychological and somatic symptoms (Smyth 1998). On the other hand, compared to non-repressors, habitual repressors also report less distress (Ward et al. 1988; Weinberger and Schwartz 1990; Weinberger, unpublished ; Swan et al. 1992; Tomaka et al. 1992; Bleiker et al. 1993). Therefore, the act of emotional expression as well as the response style of non-expression are both associated with low reported distress.

There is an area of research that studies the effects of inhibiting emotional behavior (Gross and Levenson 1993) and another area of research that is interested in the effect of thought suppression (Abramowitz et al. 2001). Participants in such studies are asked to refrain from emotional behavior, such as facial expressions, or not to think of a certain image. Gross uses the term ‘emotional suppression’ in the sense of an act and describes it as the conscious inhibition of behavioral signs of emotion, while being emotionally aroused (Gross and Levenson 1993).

Repressed Memories

Repressing memories of traumatic events concerns a complex of cognitions and emotions that is mainly limited to a certain theme or event, such as sexual abuse in childhood. This is different from repression, which concerns the tendency not to express negative emotions in general. Repression of memories is initiated by traumatic events, whereas repression is a habitual style applied in a variety of situations. Although repressing memories of traumatic events could lead to an habitual style of repression, or magnify an existing tendency to repression that does not undo the conceptual difference.

Strengthening of existing repressive tendencies in response to a traumatic condition was demonstrated in a study among women who were awaiting the outcome of diagnostic tests for breast cancer, which may be conceived as a traumatic event. An increase in the number of repressors was found after the diagnosis of breast cancer was made known to the patients, whereas no increase was found in women who appeared to be free of cancer (Kreitler et al. 1993).

In a series of studies, McNally presented evidence that those who believe they were sexually abused as children, but have no memory for these events (“repressed memories”) show a particular style of information processing, which is different from those who have never forgotten their childhood sexual abuse or have never been sexually abused (McNally 2001). Individuals with repressed memories exhibited symptoms of psychological distress, elevated levels of dissociation and absorption, superior forgetting abilities for trauma-related material and memory distortions. Most of these characteristics were also found in individuals who report having recalled long-forgotten episodes of childhood sexual abuse (“recovered memories”). These characteristics may reflect a propensity for repressing traumatic memories, a propensity for forming false memories of trauma, or a consequence of abuse itself (assuming it occurred). Anyhow, this personality profile relates to information processing distortions of trauma-related material, not to emotionally loaded material in general as found in repression. Moreover, the high distress scores of individuals with repressed memories are incompatible with the concept of repression.

Habitual Suppression

In later publications on emotion regulation, Gross shifted his attention from suppression as an act to the habitual use of suppression, which was described as a form of response modulation that involves inhibiting ongoing emotion-expressive behavior (John and Gross 2004). Inhibition of emotional experiences is not assumed, as is the case in the definition of repression. Gross even presumes that using suppression in everyday life might actually be associated with greater negative emotion experience. Acknowledging these characteristics, habitual suppression must come under the heading of anxious defensiveness.

Empirical findings indicate that habitual suppression is different from, and in some respects, the opposite of repression. Whereas habitual suppressors experience less positive and more negative emotions than other people (John and Gross 2004), repressors do not differ from other people with respect to the experience of positive emotions and they experience less negative emotions than non-repressors (Furnham et al. 2003). Moreover, habitual suppressors have a lower self-esteem and a less optimistic outlook (John and Gross 2004), whereas the opposite was found for repressors (Myers and Reynolds 2000).

Self-concealment

Larson and Chastain (1990) introduced the concept self-concealment as the trait version of the act of inhibition, studied by Pennebaker et al. 1990). The authors define self-concealment as a “predisposition to actively conceal from others personal information that one perceives as distressing or negative,” and they say that “self-concealed personal information is consciously accessible to the individual” (Larson and Chastain 1990, p. 440).

How is this concept related to repression? There are three gradual differences with repression: (1) Self-concealment concerns specific distressing secrets, whereas repression concerns negative feelings in general, although it should be said that there is a rather thin line between these two elements; (2) Self-concealment is explicitly a tendency towards voluntary and conscious inhibition, whereas repression is conceptualized as incorporating both unconscious and conscious coping strategies; (3) Self-concealment implies the awareness of distressing thought contents, whereas repression implies the inhibition to become fully aware of such thought contents. Especially this last aspect implies that self-concealment could be better placed under the heading anxious defensiveness, rather than repression.

Empirical findings support this supposed conceptual difference. While repression is often negatively related to distress reporting (Weinberger and Schwartz 1990; Weinberger, unpublished ; Swan et al. 1992; Tomaka et al. 1992; Bleiker et al. 1993; Gick et al. 1997; Vetere and Myers 2002), a positive association has been found between self-concealment and depression, anxiety and physical symptoms (Larson and Chastain 1990) and rumination (King et al. 1992). A negative relationship between self-concealment and repression (King et al. 1992; Ritz and Dahme 1996) has also been reported. In fact, (Ritz and Dahme 1996) found the lowest scores on the Self-Concealment scale (SCS; Larson and Chastain 1990) for repressors and the highest SCS scores among the (truly or defensive) high-anxious persons.

Type C Coping Style

The Type C concept was first introduced in 1980 in an abstract presented by Morris and Greer (1980), who considered this coping style as characteristic of cancer patients. The style was described as being emotionally contained, especially in stressful situations. Temoshok independently developed a similar concept, which included several elements (Kneier and Temoshok 1984), and described this coping style as ‘abrogating one’s own needs in favor of those of others, suppressing negative emotions, and being cooperative, unassertive, appeasing, and accepting. The Type C individual is considered nice, friendly and helpful to others, and rarely gets into arguments or fights... The Type C individual may be seen as chronically hopeless and helpless, even though this is not consciously recognized in the sense that the person basically believes that it is useless to express one’s needs... The Type C individual does not even try to express needs and feelings; these are hidden under a mask of normalcy and self-sufficiency’ (Temoshok 1987, pp. 558–560).

One of the repressive types, as distinguished by Weinberger and Schwartz (1990), in our view shows a remarkable resemblance to the Type C coping pattern. The characteristics mentioned for anxious defensiveness resemble the above-mentioned characteristics for individuals who use Type C coping. Both descriptions mention unassertiveness, low sensitivity to one’s own needs and feelings, abrogating one’s own needs in favor of others, emotional reliance on others, being cooperative, appeasing and accepting, and high levels of distress (obsessive worrying/ helplessness and hopelessness). Because of this similarity and the inclusion of helplessness and hopelessness in the description of this concept, the Type C response pattern seems closer to anxious defensiveness than repression.

Type D Personality

The term ‘Type D personality’ was introduced by Denollet (1997) to describe those people who are distressed, but who also inhibit the expression of emotions. Denollet developed this concept, while working in the field of cardiovascular disorders. It consists of a combination of two factors that seemed predictive for the development of coronary heart disease and hypertension. The first factor was high distress levels (anger, depression, anxiety and vital exhaustion) and the second factor was the inhibition of emotional expression. This second factor was specified as reflecting social inhibition (and introversion).

It is important to be aware that according to the description of the Type D person, the negative emotions of anger, anxiety, and depression are experienced consciously. Whereas repression and distress are often negatively related, a high level is implicated in the Type D personality. Type D persons are categorized as scoring high on distress and high on social inhibition (Denollet 2005). Therefore, the Type D personality style is explicitly the anxious defensive type.

Denial

Denial is conceived here as denying or minimizing the seriousness of a medical condition, not as denial of emotions or painful events as is commonly the case, and not as an unconscious defense against painful and overwhelming aspects of external reality, as described in psychoanalytic theory. The way denial is described in this paper—denial of diagnosis or denial of impact—is one of the several definitions quoted in the literature (Vos and Haes 2007; Moyer and Levine 1998). Greer et al. described denial in breast cancer as “apparent active rejection of any evidence about their diagnosis which might have been offered, including the evidence of breast removal, such as “it wasn’t serious, they just took off my breast as a precaution” (Greer et al. 1979, p. 786). Minimizing the impact of cancer is a milder and more realistic form of denial, and was measured in studies by Butow. (Butow et al. 1999, 2000; Brown et al. 2000). Our definition of denial indicates a clear conceptual difference between denial and repression. Repression does not specifically refer to the emotional consequences of a disease, but rather to negative emotions in general. A person might repress these emotions, while not denying the seriousness of the disease. Denial or minimizing can either be an act (an event-driven coping response) or it can reflect a habitual style of minimizing the seriousness of unpleasant events.

It is interesting that cancer studies showed opposite consequences of the two phenomena. In studies using a prospective, longitudinal design to investigate the role of psychological factors on the course of cancer, two studies found that repression predicted an unfavorable course (Jensen 1987; Weihs et al. 2000). Obversely, in four other studies denial or minimizing was found to predict a favorable course of cancer (Greer et al. 1979; Dean and Surtees 1989; Greer et al. 1990; Butow et al. 1999, 2000).

Alexithymia

The concept of alexithymia is derived from clinical observations of a cluster of specific cognitive characteristics among patients suffering from psychosomatic diseases, substance use disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorders (Nemiah et al. 1976; Bagby et al. 1997). It evolved into a theoretical construct, with the following salient features: (1) difficulty identifying feelings, (2) difficulty describing feelings, and (3) externally oriented thinking (Bagby et al. 1997).

Due to the difficulty of identifying feelings, one might assume that emotions are not expressed either. However, alexithymic persons should not be considered to be emotionally flat. Nemiah et al. reported a proneness to sudden outbursts of crying and anger in these persons, though they were unable to connect these behaviors with thoughts and fantasies (Nemiah et al. 1976). Corresponding to these observations, Sifneos reported that it was common for his patients to mention anxiety or to complain of depression (Sifneos 1967), although they used a limited vocabulary to describe their emotions. The emotions of alexithymic individuals appear to be rather diffuse, poorly differentiated and not well-represented. Taylor et al. concluded that alexithymia should be regarded not as a defense against distressing affects or fantasies, but rather as the reflection of an individual difference in the ability to process and regulate emotions cognitively (Taylor et al. 1997). They suggested that this construct is different from ‘other emotion-related constructs such as inhibition and the repressive-defensive coping style.’

The difference between alexithymia and repression is empirically supported. First, several studies have shown that the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS)—the most widely used and well-validated questionnaire for assessing alexithymic traits—appeared to be unrelated or negatively related with various measures of repression (King et al. 1992; Newton and Contrada 1994; Myers 1995; Linden et al. 1996; Taylor et al. 1997). Second, the TAS is unrelated (Linden et al. 1996), or positively related with self-reported distress (Taylor et al. 1997; Verissimo et al. 1998), whereas measures of repression are negatively related with distress.

Based on psychometric comparisons, alexithymia shows some correspondence to the sensitizing style of high-anxious persons, rather than the avoidant style of repressors. Repressive individuals often report that they are not upset despite objective evidence to the contrary, whereas alexithymic individuals acknowledge that they are upset, but have difficulty in specifying the nature of their distress.

Blunting

Miller (1987) distinguishes two types of individual differences in dealing with threatening stimuli. Monitors are those people who tend to seek information when coping with a threat, such as going to the dentist, being taken hostage or flying (information seekers), and blunters tend to avoid information when faced with a threat (distractors). There is some similarity between blunting and repression, as both repressors and high blunters avoid distressing information. Repressors avoid mainly personally relevant, emotionally loaded information. High blunters, on the contrary, avoid material about external conditions that people generally regard threatening. There is no implication in the definition that high blunters avoid expressing negative emotions because that would threaten their self-image, which is explicitly included in the description of repression.

Discussion

The way in which most people use the term ‘repression’ in an everyday context indicates that they generally understand what it actually refers to. Whether science was right to introduce the current assortment of subtle differences thus exposing the gross simplicity of society’s everyday use of the term, or whether science has ultimately entangled the term in a maze of unclear terminology is debatable. It is undebatable, however, that there is a lack of consensus about what repression is. The impression is that the many terms used in this field—repression, suppression, non-expression of negative emotions, emotional control, emotional inhibition, rationality, anti-emotionality, defensiveness and restraint—denote something similar to repression, but there is no certainty whether they can be considered synonymous, indicate a subtle variation of repression, or indicate an associated, but essentially different concept. One reason for this confusion is that definitions are rarely given, and that hardly ever is indicated how a new term relates to regularly used terms.

Repression has been defined as the tendency to inhibit—consciously or unconsciously—the experience and expression of negative emotions or unpleasant cognitions in order to prevent one’s positive self-image from being threatened. The term is used to describe an act, such as avoiding a specific memory, or a tendency or coping style (‘repressive coping style’). This paper deals with repression as a tendency or coping style. Terms whose definitions appear to agree with the definition of repression, which can therefore be considered synonyms of repression, are: non-expression of negative emotions, emotional inhibition, emotional control, anti-emotionality, rationality and self-restraint. Although these terms may all be subsumed under the heading repression, their definitions also suggest some differences concerning the motives for repression.

We tentatively made a difference between socially related and personally related repression (see Fig. 1). An example of socially related repression is ‘self-restraint’, which encompasses ‘tendencies to inhibit aggressive behavior, to exercise impulse control, to act responsibly, and to be considerate of others’ (Weinberger and Schwartz 1990, p. 382). An example of personally related repression is rationality, which is described as “the extent to which an individual uses reason and logic as a general approach to coping with the environment” (Spielberger 1988). In the first category, the tendency to inhibit the experience and expression of negative emotions in order to prevent one’s positive self-image from being threatened is (more) socially related, which reflects a self-concept that depends (more) on the approval of other people more so than personally related repression. Future research will show whether this distinction is useful or not. A study has indeed provided some empirical evidence for its validity, showing that restraint scales and emotional control scales loaded on different dimensions in a secondary factor analysis (Giese-Davis and Spiegel 2001).

By definition, repression implies (some degree of) self-deception, whereas repression may or may not include other-deception. Self-deception implies honestly believing one’s positive self-report. The overlap with repression is evident, given that “the inhibition of the experience of negative emotions or unpleasant cognitions in order to prevent one’s positive self-image from being threatened” implies self-deception. Other-deception is described as deliberately avoiding expression of negative emotions as part of the tendency to make a favorable impression on other people. Other-deception without self-deception, therefore, seems to be incoherent with the definition of repression.

Defensiveness is a broader concept than repression. Defensiveness concerns different strategies to protect oneself against being psychologically hurt, which include repression and anxious defensiveness (Weinberger and Schwartz 1990). This distinction was made on the basis of operational criteria. Although high levels of defensiveness characterize both forms, repressors report relatively low distress levels, whereas anxious defensive persons report relatively high distress levels. The division into the two defensiveness groups appears to be more than the product of an arithmetic procedure; it refers to a constellation of essential individual differences (Weinberger 1990). One essential difference concerns the two defensiveness groups’ association with distress.

We have also indicated which concepts, although sometimes associated with repression, are basically different from repression: voluntary suppression, repressed memories, habitual suppression, self-concealment, type C coping pattern, type D personality, denial, alexithymia and blunting. The first concept concerns an ‘act,’ whereas we have discussed repression as a tendency or coping style. Four of these concepts were placed under the heading anxious defensiveness, because their definitions imply experiencing high levels of negative emotions: Habitual suppression, self-concealment, type C coping style and type D personality.

Our conceptual analysis has motivated us to propose the following recommendations for future research: (1) In studies on the character and the consequences of repression one should ideally include measures of personally related and socially related repression, and—as a contrast—a measure of anxious defensiveness. (2) An acute distinction should be made when summarizing literature findings between repression and concepts that are related to, but essentially different from repression (3) Future research will need to show whether relationships between questionnaires substantiate the similarities and differences between the concepts described in this paper.

Our objective with this treatise on defensiveness-related concepts is to provide more clarity in this field. The next step in finding our way in the current maze of repression points to a review on defensiveness-related questionnaires.

Footnotes

In the publication under discussion, Weinberger used the term ‘restraint’ instead of ‘defensiveness’ and labeled this subgroup as ‘high distress—high restraint’ (Weinberger and Schwartz 1990, p. 409).

Weinberger’s et al. finding of a relationship between alexithymia and repression has been contradicted by other studies (see the later paragraph on alexithymia).

References

- Abramowitz, J. S., Tolin, D. F., & Street, G. P. (2001). Paradoxical effects of thought suppression: A meta-analysis of controlled studies. Clinical Psychological Review, 21, 683–703. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ashley, A., & Holtgraves, T. (2003). Repressors and memory: Effects of self-deception, impression management, and mood. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 284–296. [DOI]

- Bagby, R. M., Taylor, G. J., & Parker, J. D. A. (1997). The nomological domain of the alexithymia construct. In A. Vingerhoets, F. V. Bussel, & J. Boelhouwer (Eds.), The (non)expression of emotions in health and disease (pp. 95–102). Tilburg: Tilburg University Press.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Cairns, K. J. (1992). Repression and self-presentation: When audiences interfere with self-deceptive strategies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 851–862. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Beutler, L. E., Engle, D., Oro’-Beutler, M. E., Daldrup, R., & Meredith, K. (1986). Inability to express intense affect: A common link between depression and pain? Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology, 54, 752–759. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bleiker, E. M. A., Ploeg, H. M. V. D., Hendriks, J. H. C. L., Leer, J.-W. H., & Kleijn, W. C. (1993). Rationality, emotional expression and control: Psychometric characteristics of a questionnaire for research in psycho-oncology. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 37, 861–872. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Boden, J. M., & Dale, K. L. (2001). Cognitive and affective consequences of repressive coping. Current Psychology, 20, 122–137. [DOI]

- Brown, J. E., Butow, P. N., Culjak, G., Coates, A. S., & Dunn, S. M. (2000). Psychosocial predictors of outcome: Time to relapse and survival in patients with early stage melanoma. British Journal of Cancer, 83, 1448–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Butow, P. N., Coates, A. S., & Dunn, S. M. (1999). Psychosocial predictors of survival in metastatic melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 17, 2256–2263. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Butow, P. N., Coates, A. S., & Dunn, S. M. (2000). Psychosocial predictors of survival: Metastatic breast cancer. Annals of Oncology, 11, 469–474. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Davis, P. J. (1987). Repression and the inaccessibility of affective memories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 585–593. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dean, C., & Surtees, P. G. (1989). Do psychological factors predict survival in breast cancer? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 33, 561–569. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Denollet, J. (1997). Non-expression of negative emotions as a personality feature. In A. Vingerhoets, F. V. Bussel, & J. Boelhouwer (Eds.), The (non)expression of emotions in health and disease (pp. 181–192). Tilburg: Tilburg University Press.

- Denollet, J. (2005). DS14: Standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and Type D personality. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67, 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Derakshan, N., & Eysenck, M. W. (1999). Are repressors self-deceivers or other-deceivers? Cognition & Emotion, 13, 1–17. [DOI]

- Erdelyi, M. H. (1993). Repression: The mechanism and the defence. In D. M. Wegner & J. W. Pennebaker (Eds.), Handbook of mental control (pp. 126–148). Englewood Cliffs, NY: Prentice Hall.

- Erdelyi, M. H. (2001). Defense processes can be conscious or unconscious. The American Psychologist, 56, 761–762. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Freud, A. (1946). The ego and the mechanisms of defense. New York: International Universities Press.

- Furnham, A., Petrides, K. V., Sisterson, G., & Baluch, B. (2003). Repressive coping style and positive self-presentation. British Journal of Health Psychology, 8, 223–249. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Furnham, A., Petrides, K. V., & Spencer-Bowdage, S. (2002). The effects of different types of social desirability on the identification of repressors. Personality and Individual Differences, 33, 119–130. [DOI]

- Gick, M., Mcleod, C., & Hulihan, D. (1997). Absorption, social desirability, and symptoms in a behavioral medicine population. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 185, 454–458. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Giese-Davis, J., & Spiegel, D. (2001). Suppression, repressive-defensiveness, restraint, and distress in metastatic breast cancer: Separable or inseparable constructs? Journal of Personality, 69, 417–449. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Greer, S., Morris, T., & Pettingale, K. W. (1979). Psychological response to breast cancer: Effect on outcome. Lancet, 13, 785–787. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Greer, S., Morris, T., Pettingale, K. W., & Haybittle, J. L. (1990). Psychological response to breast cancer and 15-year outcome. Lancet, 335, 49–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gross, J. J., & Levenson, R. W. (1993). Emotional suppression: Physiology, self-report, and expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 970–986. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M. R. (1987). Psychobiological factors predicting the course of breast cancer. Journal Personality, 55, 317–342. [DOI] [PubMed]

- John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2004). Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of Personality, 72, 1301–1333. [DOI] [PubMed]

- King, L. A., Emmons, R. A., & Woodley, S. (1992). The structure of inhibition. Journal of Research in Personality, 26, 85–102. [DOI]

- Kneier, A. W., & Temoshok, L. (1984). Repressive coping reactions in patients with malignant melanoma as compared to cardiovascular disease patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 28, 145–155. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Koller, M., Heitmann, K., Kussmann, J., & Lorenz, W. (1999). Symptom reporting in cancer patients II: Relations to social desirability, negative affect, and self-reported health behaviors. Cancer, 86, 1609–1620. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kreitler, S., Chaitchik, S., & Kreitler, H. (1993). Repressiveness: Cause or result of cancer? Psycho-Oncology, 2, 43–54. [DOI]

- Larson, D. G., & Chastain, R. L. (1990). Self-concealment: Conceptualization, measurement, and health implications. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9, 439–455.

- Linden, W., Lenz, J. W., & Stossel, C. (1996). Alexithymia, defensiveness and cardiovascular reactivity to stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 41, 575–583. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Linden, W., Paulhus, D. L., & Dobson, K. S. (1986). Effects of response styles on the report of psychological and somatic distress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54, 309–313. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McNally, R. J. (2001). The cognitive psychology of repressed and recovered memories of childhood sexual abuse: Clinical implications. Psychiatric Annals, 31, 509–514.

- Mendolia, M., Moore, J., & Tesser, A. (1996). Dispositional and situational determinants of repression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 856–867. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Miller, S. M. (1987). Monitoring and blunting: Validation of a questionnaire to assess styles of information seeking under threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 345–353. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Morris, T., & Greer, S. (1980). A ‘Type C’ for cancer? Low trait anxiety in the pathogenesis of breast cancer. Cancer Detection Prevention, 3, Abstract 102.

- Moyer, A., & Levine, E. G. (1998). Clarification of the conceptualization and measurement of denial in psychosocial oncology research. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 20, 149–160. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Myers, L. B. (1995). Alexithymia and repression: The role of defensiveness and trait anxiety. Personality and Individual Differences, 19, 489–492. [DOI]

- Myers, L. B., & Brewin, C. R. (1996). Illusions of well-being and the repressive coping style. British Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 443–457. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Myers, L. B., & Reynolds, D. (2000). How optimistic are repressors? The relationship between repressive coping, controllability, self-esteem and comparative optimism for health-related events. Psychology and Health, 15, 677–687.

- Nemiah, J. C., Freyberger, H., & Sifneos, P. E. (1976). Alexithymia: A view of the psychosomatic process. In O. W. Hill (Ed.), Modern trends in psychosomatic medicine (pp. 430–439). London: Butterworths.

- Newton, T. L., & Contrada, R. (1992). Repressive coping and verbal-autonomic response dissociation: The influence of social context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 159–167. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Newton, T. L., & Contrada, R. J. (1994). Alexithymia and repression: Contrasting emotion-focused coping styles. Psychosomatic Medicine, 56, 457–462. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Paulhus, D. L. (1984). Two-component models of socially desirable responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 598–609. [DOI]

- Pauls, C. A., & Crost, N. W. (2004). Effects of faking on self-deception and impression management scales. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 1137–1151. [DOI]

- Pennebaker, J. W., Czajka, J. A., Cropanzano, R., & Richards, B. C. (1990). Levels of thinking. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16, 744–757. [DOI]

- Ritz, T., & Dahme, B. (1996). Repression, self-concealment and rationality/emotional defensiveness: The correspondence between three questionnaire measures of defensive coping. Personality and Individual Differences, 20, 95–102. [DOI]

- Rogers, M., & Kristjanson, L. J. (2002). The impact on sexual functioning of chemotherapy-induced menopause in women with breast cancer. Cancer Nursing, 25, 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sifneos, P. E. (1967). Clinical observations on some patients suffering from a variety of psychosomatic diseases. Acta Medicina Psychosomatica, 7, 1–10.

- Smyth, J. M. (1998). Written emotional expression: Effect sizes, outcome types and moderating variables. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 174–184. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C. D. (1988). The rationality/emotional defensiveness (R/ED) scale: Preliminary test manual. Tampa, Fl: University of South Florida.

- Stober, J., Dette, D. E., & Musch, J. (2002). Comparing continuous and dichotomous scoring of the balanced inventory of desirable responding. Journal of Personality Assessment, 78, 370–389. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Swan, G. E., Carmelli, D., Dame, A., Rosenman, R. H., & Spielberger, C. D. (1992). The Rationality/Emotional Defensiveness Scale-II. Convergent and discriminant correlational analysis in males and females with and without cancer. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 36, 349–359. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Taylor, G. J., Parker, J. D. A., & Bagby, R. M. (1997). Relationships between alexithymia and related constructs. In A. Vingerhoets, F. V. Bussel, & J. Boelhouwer (Eds.), The (non)expression of emotions in health and disease (pp. 103–114). Tilburg: Tilburg University Press.

- Temoshok, L. (1987). Personality, coping style, emotion and cancer: Towards an integrative model. Cancer Surveys, 6, 545–567. [PubMed]

- Tomaka, J., Blascovich, J., & Kelsey, R. M. (1992). Effects of self-deception, social desirability, and repressive coping on psychophysiological reactivity to stress. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 616–624. [DOI]

- Verissimo, R., Mota-Cardoso, R., & Taylor, G. (1998). Relationships between alexithymia, emotional control, and quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 67, 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vetere, A., & Myers, L. B. (2002). Repressive coping style and adult romantic attachment style: Is there a relationship? Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 799–807. [DOI]

- Vos, M. S., & Haes, J. C. J. M. D. (2007). Denial in cancer patients, an explorative review. Psycho-Oncology, 16, 12–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ward, S. E., Leventhal, H., & Love, R. (1988). Repression revisited: Tactics used in coping with a severe health threat. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 14, 735–746. [DOI]

- Watson, M., & Greer, S. (1983). Development of a questionnaire measure of emotional control. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 27, 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Weihs, K. L., Enright, T. M., Simmens, S. J., & Reiss, D. (2000). Negative affectivity, restriction of emotions, and site of metastases predict mortality in recurrent breast cancer. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 49, 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Weinberger, D. A. (1990). The construct validity of the repressive coping style. In J. L. Singer (Ed.), Repression and dissociation: Implications for personality, theory, psychopathology, and health (pp. 337–386). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Weinberger, D. A., & Schwartz, G. E. (1990). Distress and restraint as superordinate dimensions of self-reported adjustment: A typological perspective. Journal of Personality, 58, 381–417. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Weinberger, D. A., Schwartz, G. E., & Davidson, R. J. (1979). Low-anxious, high-anxious, and repressive coping styles: Psychometric patterns and behavioral and physiological responses to stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 88, 369–380. [DOI] [PubMed]