Abstract

Autophagy, a cellular process of cytoplasmic degradation and recycling, is induced in Drosophila larval tissues during metamorphosis, potentially contributing to their destruction or reorganization. Unexpectedly, we find that flies lacking the core autophagy regulator Atg7 are viable, despite severe defects in autophagy. Although metamorphic cell death is perturbed in Atg7 mutants, the larval–adult midgut transition proceeds normally, with extended pupal development compensating for reduced autophagy. Atg7−/− adults are short-lived, hypersensitive to nutrient and oxidative stress, and accumulate ubiquitin-positive aggregates in degenerating neurons. Thus, normal levels of autophagy are crucial for stress survival and continuous cellular renewal, but not metamorphosis.

[Keywords: Autophagy, Atg7, Drosophila, longevity, metamorphosis, neurodegeneration]

Autophagy is a general term for the degradation of self-material in lysosomes. During the course of the main pathway, macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy), an isolation membrane appears that envelops random portions of the cytoplasm. Sealing of the edges results in a unique double-membrane vesicle called an autophagosome, which will then fuse with a lysosome to deliver its contents for degradation and reuse. This process is controlled by a core group of ∼20 conserved autophagy-related (Atg) genes first identified in yeast (Klionsky et al. 2003). Among these, the ubiquitin-related proteins Atg8 and Atg12 and their E1- and E2-like processing enzymes are essential for autophagosome formation.

As in yeast, targeted disruption of Atg genes in mouse and Drosophila models results in a block of starvation-induced autophagy and causes an accelerated loss of viability under starvation conditions (Scott et al. 2004; Komatsu et al. 2005; Hara et al. 2006). In addition, Atg gene knockouts in these animal models have been shown to result in post-embryonic lethality even in the presence of optimal nutrients, suggesting that in higher eukaryotes, autophagy has evolved to serve additional functions beyond starvation survival. Indeed, recent reports showed that basal autophagy plays an essential role in protein quality control in mammals, by continuously degrading misfolded or damaged proteins (Komatsu et al. 2005, 2006; Hara et al. 2006), and prevents metabolic stress-induced genome instability and tumor progression (Mathew et al. 2007). During development, high levels of autophagy may also contribute to some forms of programmed cell death, as in the case of degenerating larval tissues during insect metamorphosis (Butterworth and Forrest 1984; Neufeld 2004; Penaloza et al. 2006).

We previously reported that mutations in Drosophila Atg1 cause a strong inhibition of autophagy and result in lethality at the pupal stage of development (Scott et al. 2004, 2007). However, because Atg1 homologs in other species have been found to participate in nonautophagic processes (Tomoda et al. 2004; Ogura and Goshima 2006; Zhou et al. 2007), it is unclear whether the lethality of these mutants stems from defects in autophagy or whether this may reflect other functions of Atg1. Here we report the generation of null mutations in Atg7, which encodes the single E1-like enzyme required for activation of both Atg8 and Atg12. Surprisingly, despite severely reduced levels of autophagy, Atg7 mutant flies are fully viable and fertile, and no major morphological defects are observed during metamorphosis. Emerging mutant adults are hypersensitive to stress and have a reduced life span, potentially due to accumulation of ubiquitin-positive aggregates in degenerating neurons.

Results and Discussion

Generation of Atg7 deletions

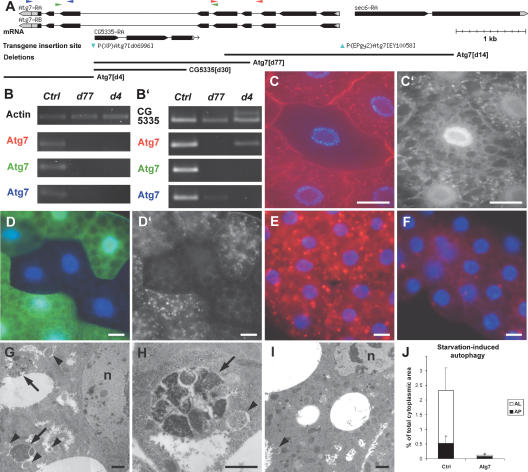

Several P-element insertions are available in the genomic region of Atg7, located in the intron between exons 6 and 7, and upstream of or downstream from the gene (Fig. 1A; data not shown). All of these lines yielded viable adults when crossed to the deletion-bearing line Df(2R)Pu66, and none of them showed a noticeable effect on starvation-induced autophagy (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Atg7 is required for starvation-induced autophagy in the fat body. (A) The genomic region of Atg7. The two P-element insertions used to generate deletions (blue arrowheads), and four deletions are shown. (B,B′) Atg7 mRNA expression was analyzed by RT–PCR in control and mutant third instar larvae. (B) No product is seen after 25 amplification cycles in Atg7 mutants, indicating strongly reduced Atg7 expression. (B′) Thirty cycles reveal the expression of C-terminal Atg7 sequences in Atg7d77 and N-terminal sequences in Atg7d4 larvae. As expected, deleted parts are not expressed in the mutants. See A for Atg7 primer locations. (C–D′) Starvation-induced autophagy is severely impaired in Atg7d4 mutant fat body clones, as shown by GFP-Atg8a labeling (C′) and Lysotracker Red staining (D′). Mutant cells are marked by lack of myrRFP (red, C) and GFP (green, D) expression, respectively. (E–J) Atg7d77 larval fat bodies show a strongly reduced autophagy in response to starvation. Very little Lysotracker staining is seen in Atg7d77 mutant fat bodies (F), while controls accumulate numerous Lysotracker-positive dots (E). Transmission EM reveals many autophagosomes (arrowheads) and autolysosomes (arrows) in control (G,H), but not in Atg7d77 fat body cells following a 3-h starvation (I). J shows a morphometric evaluation of EM images. (AP) Autophagosome; (AL) autolysosome. Error bars represent standard deviation. Bars: C–F, 10 μm; G–I, 1 μm. (B,E,G,H,J) Control: CG5335d30/Atg7d14. (B) Atg7d4: Atg7d4/Atg7d14. (B,F,I,J) Atg7d77: Atg7d77/Atg7d14. (C) FRT42D Atg7d4/CgGAL4 UAS-GFP-Atg8a FRT42D UAS-myrRFP. (D) FRT42D Atg7d4/UAS-2XeGFP FRT42D fb-GAL4.

As previously identified mutations in Drosophila Atg genes with a strong autophagy-defective phenotype were lethal (Scott et al. 2004), we initially screened for lethal lines after remobilization of the P-element Atg7EY10058, located 73 bases upstream of the predicted Atg7 transcription start site. Of the lethal lines recovered, two groups of deletions could be identified. The first contained deletions extending from the original P-element insertion site into a neighboring gene, Sec6 (data not shown). Lines in the second group had deletions extending into both Atg7 and Sec6, as in the case of Atg7d14 (Fig. 1A), which removes the transcription and translation start sites and the majority of the Atg7 coding region, resulting in a presumptive null allele. As existing Sec6 mutations described earlier were lethal (Murthy et al. 2005), we concluded that the lethality of these deletion lines could be ascribed to lack of Sec6 function. Our failure to identify any Atg7-specific events among these lethal deletions suggested that Atg7 might not be an essential gene. This was confirmed by remobilization of a second P-element located in the intron between exons 6 and 7 of Atg7. None of the recovered 54 lines that lost this element were lethal. We identified three groups of deletions based on sequence data. The first group, represented by Atg7d4, removed the last three exons of Atg7; the second group included deletions that removed most of CG5335, a gene located in the intron of Atg7 as in the case of CG5335d30; the third group consisted of deletions that completely removed CG5335 and part of Atg7, as in the case of Atg7d77, which lacks exons 5 and 6 and most of exon 4 (Fig. 1A). As these exons code for the E1-like domain of Atg7 that is required for its enzymatic activity, we concluded that Atg7d77 is a likely null allele. As expected, the Atg7d77 and Atg7d4 deletions very strongly interfered with Atg7 expression. No product could be detected by RT–PCR for the sequences removed by these deletions, respectively, and mRNA levels for the remaining portions were also very strongly reduced in both cases (Fig. 1B).

In the experiments below, we refer to Atg7d77/Atg7d14 animals as Atg7d77 or simply Atg7 mutants (homozygous mutant for Atg7, heterozygous for Sec6 and CG5335), and we use flies of the genotype CG5335d30/Atg7d14 as control (heterozygous for Atg7, Sec6, and CG5335). Most tests were repeated using flies of the genotypes Atg7d77/Df(2R)Pu66 and CG5335d30/Df(2R)Pu66, with similar results (Supplementary Table 1).

Atg7 is required for starvation-induced autophagy

To assess the role of fly Atg7 in autophagy, we stained larval fat bodies with Lysotracker Red, a vital dye used for the detection of acidic organelles including autolysosomes. We also monitored the intracellular localization of GFP-Atg8a, a widely used marker of autophagosomes. In control animals, starvation leads to accumulation of both Lysotracker Red-positive vesicles and GFP-Atg8a-positive punctate structures (Scott et al. 2004). The number of such structures was severely reduced in Atg7d4 homozygous mutant fat body cell clones (Fig. 1C,D). Similarly, starvation failed to induce punctate Lysotracker staining in fat bodies of Atg7d77 mutant larvae (Fig. 1E,F).

We used transmission electron microscopy (EM) to quantify the autophagy defect seen in Atg7d77 mutants. Following 3 h of starvation, many autophagosomes and autolysosomes were observed in control larval fat body cells (Fig. 1G,H). Atg7 mutants exhibited a strong reduction of these autophagic structures (Fig. 1I). Morphometric analysis revealed that autophagosomes occupied 0.53% and autolysosomes 1.79% of the cytoplasm in controls, whereas the volume ratio was 0.08% and 0.04% in Atg7 mutant fat body cells, respectively (Fig. 1J). Together, these results indicate that cells lacking Atg7 function are severely impaired in their ability to induce autophagy in response to starvation.

Atg7 is required for developmental autophagy in the larval midgut

At the onset of metamorphosis, autophagy is induced to high levels in larval tissues including the fat body, midgut, and salivary glands, and has been suggested to participate in the elimination of these tissues by programmed cell death events that take place during metamorphosis (Butterworth and Forrest 1984; Neufeld 2004; Penaloza et al. 2006). Accordingly, we observed numerous GFP-Atg8-positive punctate structures in the midgut gastric caeca of control larvae at the wandering stage, just prior to the onset of pupariation (Fig. 2A). Atg7 mutant gastric caeca showed a strong decrease of GFP-Atg8 dots (Fig. 2B), confirming that Atg7 is required for developmental as well as starvation-induced autophagy. Our EM studies also showed numerous autophagosomes and autolysosomes in control larval midguts, and the number and size of these structures were strongly reduced in mutant cells (Fig. 2C,D). Morphometric analysis revealed that autophagosomes occupied 0.95% and autolysosomes 3.22% of the cytoplasm in controls, whereas the volume ratio was 0.17% and 0.42% in Atg7 mutant midgut cells, respectively (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

Atg7 is required for developmental autophagy and apoptotic DNA fragmentation in the midgut. (A–E) Developmental autophagy defects in Atg7d77 mutant larval midguts. (A) Developmental autophagy results in punctate GFP-Atg8a localization in control midguts. (B) Atg7d77 mutant midguts show a more uniform GFP-Atg8a signal with very few dots. Ultrastructural analysis reveals numerous autophagosomes and autolysosomes in control (C), but not in mutant midguts (D). E shows a morphometric evaluation of EM images; labels as in Figure 1. (F–M) Adult epithelium is formed normally in Atg7d77 mutants during metamorphosis. (F,G) The larval midgut is composed mostly of large, polyploid cells, with intercalated small, diploid imaginal cells in control and mutant animals at the time of puparium formation (white prepupal stage). (H–K) The adult epithelium is formed from proliferating imaginal cells by 5 h RPF, accompanied by shortening and thickening of the entire midgut (note increased diameter in cross-section between F–H or G–I), and shedding of the larval cell layer into the lumen (dark cell masses in H,I). (I) Although appearing less condensed at this time, larval cells of Atg7 mutants are also shed into the lumen. (J,K) Formation of the adult midgut epithelium (ae) proceeds normally in both control and mutant animals. Aberrant structures reminiscent of protein aggregates were seen in the apical area of mutant midgut cells at 5 h RPF (M), in the region where control cells accumulated numerous large autolysosomes (L). TUNEL staining of white prepupal midguts reveals defects in DNA fragmentation in dying Atg7d77 larval cells (O), when compared with the robust nuclear staining seen in controls (N). Bars: A,B,F–I, 10 μm; C,D,J–M, 1 μm; N,O, 200 μm. (A,C,E,F,H,J,L,N) Control: CG5335d30/Atg7d14. (B,D,E,G,I,K,M,O) Atg7d77: Atg7d77/Atg7d14.

Loss of autophagy delays the death of larval midgut cells but causes no major developmental defects

We next asked whether the reduced autophagy in Atg7 mutant midguts influences their elimination during metamorphosis. During the prepupal stage, the larval midgut shrinks and is shed into the lumen of the forming adult midgut. We observed neither major defects in adult epithelium formation nor elimination of the larval midgut in Atg7 mutants (Fig. 2F–K; see also Supplementary Fig. 1). Shrinkage and elimination of gastric caeca were similar in control and Atg7 animals, and shedding of degenerating larval epithelium into the lumen of the forming adult midgut was completed by 16 h RPF (relative to puparium formation) as well (Supplementary Fig. 1). Interestingly, aberrant structures reminiscent of protein aggregates were observed in the apical region of mutant midgut cells at 5 h RPF, in the area where control cells accumulated numerous large autolysosomes (Fig. 2L,M).

Despite the apparently normal progression of midgut remodeling during metamorphosis, DNA fragmentation indicative of cell death that is readily detected in control midguts at the time of puparium formation was greatly reduced in Atg7 mutants (Fig. 2N,O). In addition, we observed an ∼4-h increase in the average time required to complete metamorphosis in Atg7 mutants (Fig. 3A). Although modest, this extension of the pupal period was highly significant (P < 10−20). We therefore conclude that normal levels of autophagy contribute to the timely progression through metamorphosis but are not essential for the extensive cell elimination and remodeling that occurs at this important stage of development.

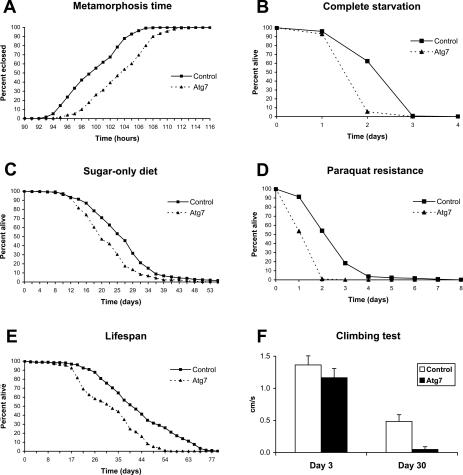

Figure 3.

Atg7 mutants show delayed metamorphosis, shorter life span, and stress sensitivity. Atg7d77 mutants eclose later than age-matched controls (A), and emerging adults die faster than control flies on complete starvation (B) or if fed a sugar-only diet (C). (D) Including 30 mM paraquat in the medium to induce oxidative stress also kills mutants faster than controls. Atg7d77 mutants show a reduced life span (E), and 30-d-old mutant flies score poorly in a climbing test relative to controls (−90.4% change, P < 10−15), while they perform almost as well as control flies at day 3 (−14.6% change, P = 0.00004) (F). (All panels) Control: CG5335d30/Atg7d14; Atg7d77: Atg7d77/Atg7d14.

Atg7 mutants are hypersensitive to nutrient and oxidative stress and have a reduced life span

As Atg7 mutants were fully viable (Supplementary Fig. 2A), we were able to investigate the role of autophagy in adult functions such as stress responses and aging. Under conditions of complete starvation or a sugar-only diet, Atg7 mutants displayed an accelerated lethality compared with control flies (Fig. 3B,C), consistent with a conserved role for autophagy in promoting starvation survival by recycling cytoplasmic constituents. Previous studies in cultured mammalian cells have suggested that autophagy may protect against oxidative damage by targeting damaged macromolecules and organelles for elimination (Cuervo et al. 2005). To test whether autophagy contributes to oxidative stress resistance in an organismal context, we measured the survival of age-matched Atg7 mutant and control flies treated with agents that induce oxidative stress. Atg7 mutants were hypersensitive to paraquat treatments, dying at a twofold faster rate than controls (Fig. 3D). Similar results were observed using hydrogen peroxide (Supplementary Fig. 2B). In addition, loss of Atg7 resulted in a reduced life span under normal conditions (Fig. 3E; see Supplementary Table 2 for detailed statistical analysis of survival curves). Atg7 mutant flies also displayed a significant age-dependent decline in climbing performance tests (Fig. 3F), an established measure of nervous system function (Martinez et al. 2007). Together, these results indicate the importance of autophagy in stress survival and longevity, potentially through elimination and recycling of damaged cellular components generated in response to induced oxidative stress or during normal aging, thus promoting constant cellular renewal.

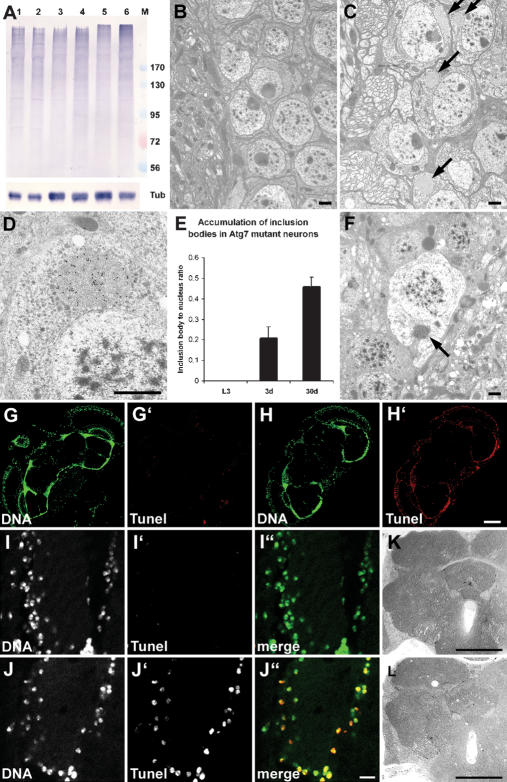

Progressive neuronal degeneration in Atg7 mutants

The age-related decline of nervous system function in Atg7 mutants suggested that the loss of autophagy in these flies leads to a neurodegenerative phenotype. Previous studies of Atg5 and Atg7 mutant mice reported an accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and progressive neurodegeneration in these animals (Hara et al. 2006; Komatsu et al. 2006). We found that ubiquitinated proteins also accumulated in aged Atg7 mutant fly head extracts, suggesting that protein aggregates form in the CNS (Fig. 4A). Ultrastructural analysis confirmed the presence of inclusion bodies in neurons of mutant, but not control fly brains (Fig. 4B,C). Immunoelectron microscopy further revealed that these aberrant structures are ubiquitin positive (Fig. 4D). The number of inclusion bodies increased over time in neurons of Atg7 mutant brains: Larval neurons never contained such structures, whereas they were readily observed in 3-d-old adults, with the highest numbers in 30-d-old adults (Fig. 4E). Accumulation of these ubiquitin-positive aggregates was associated with a progressive neurodegeneration, as dead neurons were readily identified in Atg7 mutant brains (Fig. 4F). Also, most brain cells of aged Atg7 mutants showed extensive DNA fragmentation (Fig. 4H,J), whereas we observed no TUNEL labeling in controls (Fig. 4G,I). Neurodegeneration was also revealed by moderate vacuolization of 30-d-old mutant brains, compared with controls (Fig. 4K,L). As expected, we detected no DNA fragmentation in control or Atg7 mutant brains at 3 d after eclosion (data not shown), but the presence of inclusion bodies in mutants may account for the slight decrease in climbing performance at this time. Interestingly, other tissues like indirect flight muscles were largely unaffected by the mutation, and overall ommatidial morphology was also similar to controls (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 4.

Ubiquitinated proteins accumulate in Atg7 mutant brains, associated with progressive neurodegeneration. (A) A Western blot shows accumulation of ubiquitinated high-molecular-weight proteins in aging Atg7d77 fly heads. No difference is seen between control (lane 1) and mutant (lane 2) late L3 larval samples. Accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins is already visible in 3-d-old Atg7d77 adult head extracts (lane 4, cf. control in lane 3), and becomes very obvious by day 30 (lane 6, cf. control in lane 5). Numbers next to the marker (M) refer to molecular weights in kilodaltons. β-Tubulin is shown as a loading control. (B–F) Electron micrographs reveal the presence of inclusion bodies in 30-d-old Atg7d77 (arrows in C), but not in control neurons (shown in B). (D) Immunoelectron microscopy confirms that these inclusion bodies contain ubiquitinated proteins. E shows progressive accumulation of aberrant protein aggregates in Atg7d77 mutants: No inclusion bodies are seen in late third instar larval brains, while they appear in neurons of 3-d-old males, and further accumulate by age 30 d. (F) Dead neurons are readily identified in 30-d-old mutant brains, many still containing ubiquitin-positive inclusion bodies in the degenerating cytoplasm (arrow). (G–J) TUNEL staining of horizontal brain sections shows widespread DNA fragmentation in Atg7d77 brains. (H,J) Most cells show DNA fragmentation in 30-d-old Atg7d77 brains, (G,I) while no staining is seen in controls. Moderate vacuolization is seen in 30-d-old Atg7d77 mutant brains (L), while no sign of degeneration is observed in controls (K). Bars: B–F, 1 μm; I,J, 10 μm; G,H,K,L, 150 μm. (B,G,I,K) Control: CG5335d30/Atg7d14. (C,D,F,H,J,L) Atg7d77: Atg7d77/Atg7d14.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that normal levels of autophagy are not required for viability in Drosophila and that the massive induction of autophagy that takes place during metamorphosis is not a prerequisite for the complex tissue rearrangements characteristic of this stage of development. These results also imply that lethality of previously described mutations in other Drosophila autophagy-related genes may stem from their roles in other essential processes. Consistent with this, we recently showed that the lethality of Atg1 mutants can be partially rescued by expression of a kinase-defective form of the Atg1 protein that inhibits starvation-induced autophagy (Scott et al. 2007), suggesting that one or more essential functions of Atg1 may be independent of autophagy. The identification of viable mutations in Drosophila Atg8a also supports this conclusion (Scott et al. 2007). Alternatively, the viability of Atg7 mutants may reflect a less severe disruption or a qualitative difference in autophagy compared with other Atg mutants. Analysis of null mutations in additional Atg genes will further clarify this issue.

The role of autophagy in cell death has not been fully resolved. Although autophagy is generally considered a prosurvival cellular defense pathway, elevated levels of autophagy have been shown to cause cell death, at least under certain experimental conditions (Kroemer and Jaattela 2005; Pattingre et al. 2005; Scott et al. 2007). Our results provide in vivo evidence supporting a dual role for autophagy in cell death. During metamorphosis, extremely high autophagic activity in larval tissues such as the midgut epithelium precedes DNA fragmentation and cell death. Mutation of Atg7 results in a marked decrease of autophagy and an inhibition of DNA fragmentation, suggesting that autophagy contributes to the normal cell death process in this case. As reported earlier, this cell death defect does not interfere with adult midgut epithelial development, which drives morphogenetic events during midgut reconstruction in Drosophila (Lee et al. 2002). In contrast to the case in these larval tissues, loss of Atg7 activity in the adult brain leads to DNA fragmentation and neuronal cell death, suggesting that autophagy acts to maintain neuronal health and prevent cell death in these cells. Our findings thus suggest that the net effect of autophagy on cell survival in vivo is dependent on both cell type and level of autophagic induction. Better understanding of the regulation of autophagy and identification of relevant substrates may provide new insight into neurodegenerative diseases and aging.

Materials and methods

P-element excisions and mutant fat body cell clones were generated as described earlier (Scott et al. 2007). Three- to five-day-old males were treated as follows: For complete starvation and the sugar-only diet, a paper towel soaked in water or 20% sucrose solution was placed in vials. Additional liquid was added as needed, and dead flies were counted daily. Paraquat or H2O2 was stirred into the food at a final concentration of 30 mM or 1%, respectively, and dead flies were counted daily. For life-span analysis, newly eclosed males were transferred to fresh food every 2–3 d, and dead flies were counted. Climbing assays were performed as described (Martinez et al. 2007). See the Supplemental Material for additional procedures.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sarolta Pálfia and Mariann Saródy for the excellent technical help, and BDSC and DSHB for providing flies and reagents. This work was supported by grants NIH RO1 GM62509 (to T.P.N.), MEDICHEM 1/047 NKFP, and RKC-06/OMFB-00598/2007 (to M.S.). G.J. is a Bólyai Fellow.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1600707

References

- Butterworth F.M., Forrest E.C., Forrest E.C. Ultrastructure of the preparative phase of cell death in the larval fat body of Drosophila melanogaster. Tissue Cell. 1984;16:237–250. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(84)90047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo A.M., Bergamini E., Brunk U.T., Droge W., Ffrench M., Terman A., Bergamini E., Brunk U.T., Droge W., Ffrench M., Terman A., Brunk U.T., Droge W., Ffrench M., Terman A., Droge W., Ffrench M., Terman A., Ffrench M., Terman A., Terman A. Autophagy and aging: The importance of maintaining ‘clean’ cells. Autophagy. 2005;1:131–140. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.3.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T., Nakamura K., Matsui M., Yamamoto A., Nakahara Y., Suzuki-Migishima R., Yokoyama M., Mishima K., Saito I., Okano H., Nakamura K., Matsui M., Yamamoto A., Nakahara Y., Suzuki-Migishima R., Yokoyama M., Mishima K., Saito I., Okano H., Matsui M., Yamamoto A., Nakahara Y., Suzuki-Migishima R., Yokoyama M., Mishima K., Saito I., Okano H., Yamamoto A., Nakahara Y., Suzuki-Migishima R., Yokoyama M., Mishima K., Saito I., Okano H., Nakahara Y., Suzuki-Migishima R., Yokoyama M., Mishima K., Saito I., Okano H., Suzuki-Migishima R., Yokoyama M., Mishima K., Saito I., Okano H., Yokoyama M., Mishima K., Saito I., Okano H., Mishima K., Saito I., Okano H., Saito I., Okano H., Okano H., et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky D.J., Cregg J.M., Dunn W.A., Emr S.D., Sakai Y., Sandoval I.V., Sibirny A., Subramani S., Thumm M., Veenhuis M., Cregg J.M., Dunn W.A., Emr S.D., Sakai Y., Sandoval I.V., Sibirny A., Subramani S., Thumm M., Veenhuis M., Dunn W.A., Emr S.D., Sakai Y., Sandoval I.V., Sibirny A., Subramani S., Thumm M., Veenhuis M., Emr S.D., Sakai Y., Sandoval I.V., Sibirny A., Subramani S., Thumm M., Veenhuis M., Sakai Y., Sandoval I.V., Sibirny A., Subramani S., Thumm M., Veenhuis M., Sandoval I.V., Sibirny A., Subramani S., Thumm M., Veenhuis M., Sibirny A., Subramani S., Thumm M., Veenhuis M., Subramani S., Thumm M., Veenhuis M., Thumm M., Veenhuis M., Veenhuis M., et al. A unified nomenclature for yeast autophagy-related genes. Dev. Cell. 2003;5:539–545. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M., Waguri S., Ueno T., Iwata J., Murata S., Tanida I., Ezaki J., Mizushima N., Ohsumi Y., Uchiyama Y., Waguri S., Ueno T., Iwata J., Murata S., Tanida I., Ezaki J., Mizushima N., Ohsumi Y., Uchiyama Y., Ueno T., Iwata J., Murata S., Tanida I., Ezaki J., Mizushima N., Ohsumi Y., Uchiyama Y., Iwata J., Murata S., Tanida I., Ezaki J., Mizushima N., Ohsumi Y., Uchiyama Y., Murata S., Tanida I., Ezaki J., Mizushima N., Ohsumi Y., Uchiyama Y., Tanida I., Ezaki J., Mizushima N., Ohsumi Y., Uchiyama Y., Ezaki J., Mizushima N., Ohsumi Y., Uchiyama Y., Mizushima N., Ohsumi Y., Uchiyama Y., Ohsumi Y., Uchiyama Y., Uchiyama Y., et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol. 2005;169:425–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M., Waguri S., Chiba T., Murata S., Iwata J., Tanida I., Ueno T., Koike M., Uchiyama Y., Kominami E., Waguri S., Chiba T., Murata S., Iwata J., Tanida I., Ueno T., Koike M., Uchiyama Y., Kominami E., Chiba T., Murata S., Iwata J., Tanida I., Ueno T., Koike M., Uchiyama Y., Kominami E., Murata S., Iwata J., Tanida I., Ueno T., Koike M., Uchiyama Y., Kominami E., Iwata J., Tanida I., Ueno T., Koike M., Uchiyama Y., Kominami E., Tanida I., Ueno T., Koike M., Uchiyama Y., Kominami E., Ueno T., Koike M., Uchiyama Y., Kominami E., Koike M., Uchiyama Y., Kominami E., Uchiyama Y., Kominami E., Kominami E., et al. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441:880–884. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G., Jaattela M., Jaattela M. Lysosomes and autophagy in cell death control. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:886–897. doi: 10.1038/nrc1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.Y., Simon C.R., Woodard C.T., Baehrecke E.H., Simon C.R., Woodard C.T., Baehrecke E.H., Woodard C.T., Baehrecke E.H., Baehrecke E.H. Genetic mechanism for the stage- and tissue-specific regulation of steroid triggered programmed cell death in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 2002;252:138–148. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez V.G., Javadi C.S., Ngo E., Ngo L., Lagow R.D., Zhang B., Javadi C.S., Ngo E., Ngo L., Lagow R.D., Zhang B., Ngo E., Ngo L., Lagow R.D., Zhang B., Ngo L., Lagow R.D., Zhang B., Lagow R.D., Zhang B., Zhang B. Age-related changes in climbing behavior and neural circuit physiology in Drosophila. Dev. Neurobiol. 2007;67:778–791. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R., Kongara S., Beaudoin B., Karp C.M., Bray K., Degenhardt K., Chen G., Jin S., White E., Kongara S., Beaudoin B., Karp C.M., Bray K., Degenhardt K., Chen G., Jin S., White E., Beaudoin B., Karp C.M., Bray K., Degenhardt K., Chen G., Jin S., White E., Karp C.M., Bray K., Degenhardt K., Chen G., Jin S., White E., Bray K., Degenhardt K., Chen G., Jin S., White E., Degenhardt K., Chen G., Jin S., White E., Chen G., Jin S., White E., Jin S., White E., White E. Autophagy suppresses tumor progression by limiting chromosomal instability. Genes & Dev. 2007;21:1367–1381. doi: 10.1101/gad.1545107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy M., Ranjan R., Denef N., Higashi M.E., Schupbach T., Schwarz T.L., Ranjan R., Denef N., Higashi M.E., Schupbach T., Schwarz T.L., Denef N., Higashi M.E., Schupbach T., Schwarz T.L., Higashi M.E., Schupbach T., Schwarz T.L., Schupbach T., Schwarz T.L., Schwarz T.L. Sec6 mutations and the Drosophila exocyst complex. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:1139–1150. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld T.P. Role of autophagy in developmental cell growth and death: Insights from Drosophila. In: Klionsky D.J., editor. Autophagy. Landes Bioscience; Georgetown, TX: 2004. pp. 224–232. [Google Scholar]

- Ogura K., Goshima Y., Goshima Y. The autophagy-related kinase UNC-51 and its binding partner UNC-14 regulate the subcellular localization of the Netrin receptor UNC-5 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 2006;133:3441–3450. doi: 10.1242/dev.02503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattingre S., Tassa A., Qu X., Garuti R., Liang X.H., Mizushima N., Packer M., Schneider M.D., Levine B., Tassa A., Qu X., Garuti R., Liang X.H., Mizushima N., Packer M., Schneider M.D., Levine B., Qu X., Garuti R., Liang X.H., Mizushima N., Packer M., Schneider M.D., Levine B., Garuti R., Liang X.H., Mizushima N., Packer M., Schneider M.D., Levine B., Liang X.H., Mizushima N., Packer M., Schneider M.D., Levine B., Mizushima N., Packer M., Schneider M.D., Levine B., Packer M., Schneider M.D., Levine B., Schneider M.D., Levine B., Levine B. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell. 2005;122:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penaloza C., Lin L., Lockshin R.A., Zakeri Z., Lin L., Lockshin R.A., Zakeri Z., Lockshin R.A., Zakeri Z., Zakeri Z. Cell death in development: Shaping the embryo. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2006;126:149–158. doi: 10.1007/s00418-006-0214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott R.C., Schuldiner O., Neufeld T.P., Schuldiner O., Neufeld T.P., Neufeld T.P. Role and regulation of starvation-induced autophagy in the Drosophila fat body. Dev. Cell. 2004;7:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott R.C., Juhasz G., Neufeld T.P., Juhasz G., Neufeld T.P., Neufeld T.P. Direct induction of autophagy by atg1 inhibits cell growth and induces apoptotic cell death. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomoda T., Kim J.H., Zhan C., Hatten M.E., Kim J.H., Zhan C., Hatten M.E., Zhan C., Hatten M.E., Hatten M.E. Role of Unc51.1 and its binding partners in CNS axon outgrowth. Genes & Dev. 2004;18:541–558. doi: 10.1101/gad.1151204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Babu J.R., da Silva S., Shu Q., Graef I.A., Oliver T., Tomoda T., Tani T., Wooten M.W., Wang F., Babu J.R., da Silva S., Shu Q., Graef I.A., Oliver T., Tomoda T., Tani T., Wooten M.W., Wang F., da Silva S., Shu Q., Graef I.A., Oliver T., Tomoda T., Tani T., Wooten M.W., Wang F., Shu Q., Graef I.A., Oliver T., Tomoda T., Tani T., Wooten M.W., Wang F., Graef I.A., Oliver T., Tomoda T., Tani T., Wooten M.W., Wang F., Oliver T., Tomoda T., Tani T., Wooten M.W., Wang F., Tomoda T., Tani T., Wooten M.W., Wang F., Tani T., Wooten M.W., Wang F., Wooten M.W., Wang F., Wang F. Unc-51-like kinase 1/2-mediated endocytic processes regulate filopodia extension and branching of sensory axons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:5842–5847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701402104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]