Abstract

Study Objectives:

To assess the effects of zolpidem and zaleplon on nocturnal sleep and breathing patterns at altitude, as well as on daytime attention, fatigue, and sleepiness.

Design:

Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial.

Setting:

3 day and night alpine expedition at 3,613 m altitude.

Participants:

12 healthy male trekkers.

Procedure:

One week spent at 1,000 m altitude (baseline control), followed by 3 periods of 3 consecutive treatment nights (N1-3) at altitude, to test 10 mg zolpidem, 10 mg zaleplon, and placebo given at 21:45.

Measures:

Sleep from EEG, actigraphy and sleep logs; overnight arterial saturation in oxygen (SpO2) from infrared oximetry; daytime attention, fatigue and sleepiness from a Digit Symbol Substitution Test, questionnaires, and sleep logs; acute mountain sickness (AMS) from the Lake Louise questionnaire.

Results:

Compared to baseline control, sleep at altitude was significantly impaired in placebo subjects as shown by an increase in the amount of Wakefulness After Sleep Onset (WASO) from 17 ± 8 to 36 ± 13 min (P<0.05) and in arousals from 5 ± 3 to 20 ± 8 (P<0.01). Slow wave sleep (SWS) and stage 4 respectively decreased from 26.7% ± 5.8% to 20.6% ± 5.8% of total sleep time (TST) and from 18.2% ± 5.2% to 12.4% ± 3.1% TST (P<0.05 and P<0.001, respectively). Subjects also complained from a feeling of poor sleep quality combined with numerous O2 desaturation episodes. Subjective fatigue and AMS score were increased. Compared to placebo control, WASO decreased by ~6 min (P<0.05) and the sleep efficiency index increased by 2% (P<0.01) under zaleplon and zolpidem, while SWS and stage 4 respectively increased to 22.5% ± 5.4% TST (P<0.05) and to 15.0% ± 3.4% TST (P<0.0001) with zolpidem only; both drugs further improved sleep quality. No adverse effect on nighttime SpO2, daytime attention level, alertness, or mood was observed under either hypnotic. AMS was also found to be reduced under both medications.

Conclusions:

Both zolpidem and zaleplon have positive effects on sleep at altitude without adversely affecting respiration, attention, alertness, or mood. Hence, they may be safely used by climbers.

Citation:

Beaumont M; Batéjat D; Piérard C; Van Beers P; Philippe M; Léger D; Savourey G; Jouanin JC. Zaleplon and zolpidem objectively alleviate sleep disturbances in mountaineers at a 3,613 meter altitude. SLEEP 2007;30(11):1527-1533.

Keywords: Polysomnography, sleep quality, control of breathing, hypobaric hypoxia, zolpidem, zaleplon, cognitive performance

INTRODUCTION

MOUNTAIN CLIMBERS EXPOSED TO HIGH ALTITUDE OFTEN SHOW POOR SLEEP QUALITY (I.E., SLEEP FRAGMENTATION, INCREASED LIGHT SLEEP, DECREASED slow wave and REM sleep1,2). Concurrently, respiration is disturbed by periodic breathing with apneic episodes and subsequent swings in arterial saturation in oxygen (SpO2). Periodic breathing may also be the cause of frequent arousals.3 Conversely, arousal from sleep may induce ventilation instability.4 Poor sleep quality may adversely affect daytime mental performance and motor function,5 and sleepiness may enhance risk for potential hazards.

Hypnotic drugs are commonly used by climbers to relieve poor sleep at high altitude levels. By reducing the frequency of arousals, the use of hypnotic drugs may further reduce the extent of periodic breathing. Benzodiazepines such as loprazolam (1 mg) and temazepam (10 mg) have been studied in trekkers during high-altitude expeditions.2,6,7 In healthy subjects exposed one night at a simulated altitude of 4,000 meters, non-benzodiazepines such as zolpidem (10 mg) and zaleplon (10 mg) have also been found to bear positive effects on sleep quality without adverse impact on nighttime ventilation or cognitive performance the following morning.8

The present study was designed to assess the safety and effectiveness on sleep of zolpidem and zaleplon in subjects exposed to an altitude of 3,613 m over 3 nights of rest and 2 days of cognitive and physical activity in the Alps. Zaleplon and zolpidem may prove even more beneficial than temazepam as hypnotic agents for use among mountain climbers due to a shorter duration of cognitive impairment; indeed, as opposed to temazepam, zaleplon, and zolpidem exhibit a faster elimination rate (half-life of zaleplon and zolpidem 1 h and 2.4 h vs. 8.4 h for temazepam).9–11

METHODS

Study Design

A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, cross-over design was used. The protocol was approved by the ethical committee and registered at the French Ministry of Health. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject, in keeping with legal requirements.

Subjects

A homogeneous group involving 12 healthy male trainees (age: 22.2 ± 0.6 years, body height: 177.5 ± 1.3 cm; body weight: 69.5 ± 0.8 kg; body mass index 22.1 ± 0.6 kg/m2) volunteered for this study. All underwent thorough medical and biological examination prior to the experiment. They completed the questionnaire designed by Horne and Östberg12 to ensure that they were neither “morning” nor “evening” types. The volunteers had no record history of sleep disorders, addiction, or neurological or psychiatric disorders. They were all nonsmokers and reported caffeine consumption <3 cups of coffee/day. None of the subjects underwent any medical treatment at the time of our experiment.

Medication

Medication was conditioned by the Central Pharmacy of the Armed Forces in hard gelatine capsules containing the test substances (zolpidem 10 mg, zaleplon 10 mg, or placebo). The dose of each active treatment was that recommended by the manufacturers for adult patients, i.e., 10 mg of zaleplon (not marketed in France) and 10 mg of zolpidem.

Measures

Nighttime Sleep and Ventilation Parameters

Sleep architecture was assessed through polysomnographic recordings, including electroencephalography (EEG), electro-oculography of each eye and chin electromyography using Embla numerical recorders (Resmed SA, Saint Priest, France). Sleep was analyzed from the EEG signals, according to standard criteria13 by a member of our research team who had no knowledge of the medication administered to the subjects. The following variables were calculated: amount of wakefulness after sleep onset (WASO), sleep period time (time from falling asleep to last awakening), total sleep time (TST: difference between sleep period and WASO), sleep efficiency index (TST/time in bed) and sleep onset latency (time from lights out to the 1st episode of stage 2 sleep). Besides WASO, sleep fragmentation was assessed by scoring EEG arousals defined as wakefulness episodes of 3-15 sec.13

Objective evaluation of sleep was also carried out through continuous wrist actigraphy.14 Subjects wore a piezoelectric accelerometer (Actiwatch, Cambridge Neurotechnology Ltd, Cambridge, England) on the nondominant wrist throughout the night. This device provided us with the opportunity to measure time spent in bed, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and sleep latency. There is a solid correlation between sleep parameters estimated by actimetry and those estimated by polysomnography.15 Actimetry is proposed as a useful tool to measure the impact of insomnia treatments.15

Sleep was subjectively evaluated through sleep logs completed after wake-up phase. Sleep log questions bore on such items as: sleep latency (<15 min, 15-30 min, 30-45 min, > 45 min), awakenings, and sleep periods (noted on a 24-h scale with a precision of 15 min), sleep quality (light, intermediate, deep), dream quality (pleasant, unpleasant), wake up quality (very easy to very difficult), and subjective appraisal of sleep duration (sufficient or not).

Ventilation was assessed on account of arterial saturation in oxygen (SpO2) measured by continuous arterial pulse oximetry. Oxygen desaturation events determined as drops in SpO2 > 4% below baseline were also taken into account to reflect the high altitude-related level of periodic breathing.16

Daytime Measurements

Attention capacity was measured with the digit symbol substitution test (DSST).17 It consisted in substituting figures by symbols on 10 sheets, at the rate of 20 figures per line, 6 lines per sheet. The correspondence between figures and symbols was the same for a given sheet but was different from sheet to sheet to avoid any training effect. Subjects were given 1 min to fill in one sheet. The number of right substitutions was assessed: the higher the number of right answers, the higher the attention rate.

The level of subjective fatigue was assessed using the Samn-Perelli questionnaire which was scored as follows: 2 points for a “better than” answer, 1 point for a “same as” answer, and 0 points for a “worse than” answer. Scores ranged from 0 (extremely fatigued) to 20 (extremely alert).18,19

Sleepiness was measured using the sleepiness scale of the Karolinska Institute,20 which produced a score on a scale from 1 (very alert) to 9 (very sleepy). Mood (alertness, calmness, and contentedness) was assessed from the 16 items of the Bond and Lader visual analogue scale.21 The occurrence of acute mountain sickness was assessed by way of the Lake Louise questionnaire.22

Experimental Protocol

The subjects were housed and trained over 5 days at the Military School of High Mountain, Chamonix, France (altitude: 1,000 m, barometric pressure: 898 hPa), and their routines were identical. During this period, they were familiarized with the experimental tests and measurements. The Chamonix altitude of 1,000 m requires no physiological adjustment in young healthy subjects and tests performed there were considered as baseline control. To become accustomed to the EEG recording procedure, subjects were fitted with EEG electrodes during the 5 consecutive nights: only the data of the last baseline control night, however, were recorded, to avoid the first-night effect.23 This reference week was followed by 3 periods of 3 treatment nights and following days spent at the altitude of 3,613 meters (barometric pressure: 649 hPa). Such altitude was reached by the subjects within a few hours so that no process of adjustment to altitude could occur. The nights were spent in a hut (“Cosmiques” hut) in the French Alps and the days were dedicated to various mountain activities. The 3 treatment periods were separated by at least 7 days of wash-out spent in the baseline control environmental conditions in Chamonix. Drugs under scrutiny were given orally in random order using a double-blind, cross-over design. Within one treatment period, a given subject received the same medication over the 3 nights.

During the experimental nights (between 19:00 and 21:00) subjects were fitted with EEG electrodes that were stuck on the skull using collodion. At 21:00, they completed the Lake Louise questionnaire and they were equipped with the actigraph, the SpO2 finger probe, and the oronasal thermosensor. They were given the medication (zolpidem, zaleplon, or placebo) at 21:45. Lights were switched off at 22:00; a signal was recorded on the tape recorders of the subjects to document the beginning of time in bed. Sleep and ventilatory parameters were recorded at the same time for all subjects until 05:00, wake-up time. Equipment was then removed and the subjects were asked to complete sleep logs and the Lake Louise questionnaire before having breakfast. From 06:00 to 06:30, the volunteers underwent DSST and completed Karolinska, Samn-Perelli, and Bond and Lader scales (morning session). Subsequently, the subjects underwent trekking throughout the day and came back to the hut at 17:00. One hour later, all scales and DSST were completed again (evening session).

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome for our study was sleep quality determined by the amount of slow wave sleep (known for its positive impact on recovery) and by the amount of sleep fragmentation (number of arousals and amount of wakefulness after sleep onset). Indeed, the high altitude-related decreased SWS and increased sleep fragmentation as factors of daytime sleepiness and impaired cognitive performance are well documented. The secondary outcomes were the parameters reflecting high altitude related periodic breathing (number of decreased SpO2 events, averaged SpO2), scores of daytime fatigue, sleepiness, mood and attention, as well as the score of acute mountain sickness.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of different variables was carried out from means of successive nights or days for each drug period spent at altitude, except for scores of acute mountain sickness.

The normality of all variables was checked using Skewness and Kurtosis tests. If the distribution of variables was non-Gaussian, a logarithmic transformation was applied. Subsequently a linear mixed model with treatment as fixed effect, baseline control as covariate and subject as random effect was performed. Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison adjustment was used for treatment comparisons at high altitude. In case of non-Gaussian distribution, comparisons between treatments were done with Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

The comparison between baseline control and high altitude levels was carried out with paired t-Test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test in keeping with the distribution of variables.

The rejection level in statistical tests was equal to 5%.

All statistical analyses were made with SAS software (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Sleep and Ventilatory Data (Polysomnography and Actigraphy)

Effect of Altitude on Sleep and Ventilatory Parameters

Sleep architecture was significantly influenced at altitude level. Main sleep and respiratory parameters are presented in Table 1. In comparison with EEG recordings from the baseline control night, sleep under placebo at high altitude was fragmented, as demonstrated by a significant increase in the number of 3-sec to 15-sec arousals from 5 ± 3 to 20 ± 10 (P <0.0001) and in WASO from 17 ± 8 to 36 ± 13 min (P <0.0001), while the sleep efficiency index significantly decreased from 94% ± 8% to 91% ± 4% (P <0.01). A substantial decrease in sleep onset latency was also found (P < 0.0001). Looking at sleep architecture, SWS occurred 13 min earlier (P <0.0001) and decreased from 26.7% ± 5.8% to 20.6% ± 5.8% TST (P <0.0001).

Table 1.

Sleep Architecture and Ventilation Parameters (Means ± SEMs)

| Parameters | Baseline control | Altitude + placebo | Altitude + zaleplon | Altitude + zolpidem |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep onset latency, min | 14 ± 1 | 2 ± 1*** | 3 ± 1*** | 3 ± 2*** |

| Sleep period time, min | 406 ± 1 | 418 ± 1*** | 417 ± 1*** | 416 ± 2*** |

| WASO, min | 17 ± 8 | 36 ± 13*** | 30 ± 13 § | 29 ± 15 § |

| TST, min | 381 ± 31 | 381 ± 15 | 388 ± 11 | 387 ± 10 |

| Sleep efficiency index, % | 94 ± 8 | 91 ± 4** | 93 ± 3 §§ | 93 ± 3 §§ |

| Stage 1, % TST | 7.4 ± 2.6 | 9.1 ± 3.3* | 7.7 ± 2.8 §§ | 7.8 ± 2.7 §§ |

| Stage 2, % TST | 47.6 ± 6.1 | 51.4 ± 8.1 | 52.4 ± 7.3 | 53.2 ± 6.7 |

| Stage 4, % TST | 18.2 ± 5.0 | 12.4 ± 4.1** | 13.1 ± 4.2*** | 15.0 ± 3.9 §§§/$$ |

| SWS, min | 101 ± 20 | 77 ± 21** | 81 ± 23 | 86 ± 22 §§ |

| SWS (1st half), min | 76 ± 16 | 58 ± 19** | 65 ± 19§§ | 72 ± 17 §§§/$$ |

| SWS (2nd half), min | 25 ± 7 | 20 ± 7 | 16 ± 6 | 15 ± 9 |

| Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep, % TST | 18.3 ± 4.2 | 18.9 ± 4.1 | 19.0 ± 5.0 | 16.6 ± 7.2 |

| SWS latency, min | 33 ± 11 | 20 ± 18*** | 18 ± 13*** | 19 ± 15*** |

| REM sleep latency, min | 99 ± 48 | 86 ± 27 | 80 ± 15 | 100 ± 13 |

| Sleep quality (scored in arbitrary units) | 6.7 ± 0.3 | 6.2 ± 0.9** | 6.6 ± 0.8 §§ | 6.5 ± 0.8 §§ |

| Subjective SEI (%) | 96 ± 5 | 89 ± 13** | 94 ± 11 § | 93 ± 12 § |

| Mean SpO2, % | 96 ± 1 | 83 ± 3*** | 84 ± 2*** | 82 ± 4*** |

| Lowest SpO2, % | 90 ± 0 | 70 ± 6*** | 69 ± 6*** | 70 ± 7*** |

| 4% O2 desaturation events per hour of sleep | 0 ± 0 | 10 ± 12*** | 12 ± 11*** | 10 ± 6*** |

| Number of arousals | 5 ± 3 | 20 ± 10*** | 18 ± 12*** | 19 ± 11*** |

Abbreviations: see text. Statistics: significant difference from baseline control data: *, **, *** (P<0.05, P<0.01, P<0.0001, respectively); significant difference from altitude + placebo: §, §§, §§§ (P<0.05, P<0.01, P<0.0001, respectively); significant difference from altitude + zaleplon: $$ (P<0.01). Primary outcomes are shown in bold font.

Sleep fragmentation at altitude level was associated with numerous episodes of O2 desaturation events (about 10/h sleep) reflecting the occurrence of periodic breathing episodes. The mean and lowest SpO2 values at altitude were significantly lower than baseline control throughout the altitude period.

Sleep logs confirmed the detrimental impact of altitude over sleep (Table 1). Subjects felt that their sleep was of poor quality (P <0.01) and the sleep efficiency index was also subjectively decreased (P <0.01).

Effect of Zolpidem and Zaleplon on Sleep and Ventilatory Patterns at Altitude Level

Both zolpidem and zaleplon had significant positive effects on sleep at altitude (Table 1). Sleep fragmentation was significantly reduced: with respect to placebo controls, WASO decreased by 6 min with zaleplon (df: 2, F: 3.46, P <0.05) and zolpidem (df: 2, F: 3.46, P <0.05), while the sleep efficiency index increased by 2.5% under both agents (df: 2, F: 5.20, P <0.01). Furthermore, actigraphy showed a significant decrease in the number of wrist movements with zaleplon and zolpidem (P <0.01, P <0.05, respectively), providing further evidence for reduced sleep fragmentation. However, neither zaleplon nor zolpidem reduced the number of arousals. Sleep onset latency under either drug was as low as the value obtained under placebo.

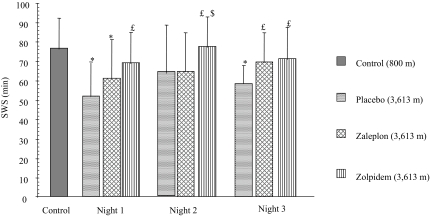

Looking at sleep architecture with respect to placebo control, SWS duration was significantly lengthened by zolpidem (+9.2%, df: 2, F: 4.09, P <0.01). To take into account the pharmacokinetics of either drug, statistics were also conducted on the basis of half-night periods (1st half: 22:00-01:30; 2nd half: 01:30-05:00). SWS was increased with zolpidem by 24% compared with placebo (df: 2, F: 17.32, P <0.0001) and by 12% compared to zaleplon (df: 2, F: 3.76, P <0.01) during the 1st half-night only (Figure 1, Table 1).

Figure 1.

SWS duration (mean values ± SEMs) in baseline control (1,000 m) and altitude conditions (placebo control, zaleplon and zolpidem) along the first half (22:00-01:30) for each night. *: significant difference from baseline control condition, P<0.05; £ and $: significant difference from altitude + placebo and from altitude + zaleplon conditions respectively, P<0.05.

Subjects expressed a significant positive effect of zaleplon and zolpidem on subjective sleep quality and sleep efficiency (P <0.01, Table 1).

Neither zolpidem nor zaleplon influenced respiratory parameters at altitude. Compared to placebo control, the O2 desaturation events per hour of sleep and the mean or lowest SpO2 were not significantly affected by either drug (n.s.; table 1).

Subjective Fatigue, Attention, Sleepiness and Mood (Table 2)

Table 2.

Subjective Fatigue, Attention Level, Sleepiness and Mood (Means ± SEMs) Assessed by the Samn-Perelli Questionnaire, the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST), the Karolinska Institute Sleepiness Scale and the Bond and Lader Visual Analogue Scale

| Parameters | Baseline control | Altitude + placebo | Altitude + zaleplon | Altitude + zolpidem | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective fatigue | M | 11 ± 3 | 7 ± 3*** | 8 ± 3** | 8 ± 3** |

| E | 10 ± 2 | 11 ± 3 | 11 ± 4 | 10 ± 4 | |

| Attention level | M | 130 ± 25 | 147 ± 30** | 153 ± 31** | 155 ± 33** |

| E | 151 ± 32 | 162 ± 31** | 169 ± 33** / § | 170 ± 32** / § | |

| Sleepiness | M | 3 ± 1 | 5 ± 1 | 5 ± 2 | 5 ± 1 |

| E | 5 ± 2 | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | |

| Mood | |||||

| Alertness | M | 61 ± 12 | 54 ± 13 | 58 ± 16 | 58 ± 12 |

| E | 85 ± 13 | 76 ± 14* | 71 ± 20* | 72 ± 16* | |

| Contentedness | M | 73 ± 14 | 68 ± 14 | 70 ± 16 | 66 ± 15 |

| E | 83 ± 17 | 77 ± 17 | 79 ± 14 | 74 ± 18 | |

| Calmness | M | 76 ± 14 | 74 ± 14 | 77 ± 13 | 69 ± 13 |

| E | 63 ± 12 | 64 ± 22 | 65 ± 20 | 64 ± 20 |

For each item, morning (06:00-06:30) and evening (17:30-18:00) values are shown on upper (M) and lower (E) lines.

Statistics: significant difference from baseline control data: *, **, *** (P<0.05, P<0.01, P<0.0001, respectively); significant difference from altitude + placebo: §, (P<0.05).

Comparisons between altitude and baseline control conditions exhibited the negative impact of altitude on subjective fatigue (P <0.0001) in the morning and on alertness (P <0.05) in the evening, under all treatment conditions. Considering the attention capacity, the digit symbol substitution test showed an increased level in all altitude conditions compared to baseline control (P <0.01) with a more marked effect under both hypnotics compared with placebo control in the evening (df: 129, F: 3.68, P <0.05).

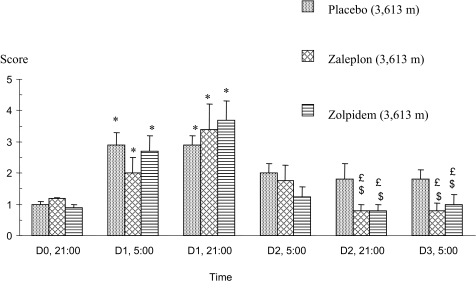

Tolerance to Altitude

The Lake Louise questionnaire—filled out at 05:00 just after wake-up and at 21:00 before going to bed—revealed headaches and tiredness in the three drug groups during the first day (D1) spent at 3,613 m (Figure 2), providing evidence of the occurrence of an acute mountain sickness at its first degree. This may be accounted for by the fast ascent to the hut of subjects not yet adjusted to the environment.

Figure 2.

Score obtained with the Lake Louise questionnaire used to assess the occurrence of acute mountain sickness at 3,613 m of altitude. *: significant difference from the data obtained before taking the medications after the arrival at 3,613 m of altitude (D0, 21:00); £: significant difference from the maximal score obtained on D1 at 21:00; $: significant difference vs. placebo control at the same time; P<0.05. Scores are mean values ± SEMs.

Scores significantly decreased the following days in subjects who were given either hypnotic drug as opposed to placebo.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to objectively evaluate the efficacy of zaleplon and zolpidem on sleep using polysomnography, and to assess the potential unwanted effects of these medications on cognitive functions in healthy trekkers exposed to real high mountain conditions throughout three days and nights.

The main findings of our current experiment stand as follows:

The hypnotics, particularly zolpidem, do improve sleep quality (less amount of WASO, better sleep efficiency, greater amount of slow wave sleep, i.e. of recovery sleep) at high altitude without any additional impairment in respiration.

Despite positive effects on sleep, cognitive functions were not found to be improved by either drug, except attention level in the evening. Nevertheless, no single unwanted side effect of either medication was observed on daytime alertness, wakefulness, or mood.

Acute mountain sickness was further relieved under zaleplon and zolpidem intake after the first night spent at altitude.

Our placebo control subjects presented the sleep disturbances that are classically observed at high altitude2,6: increased light sleep and poor deep sleep with frequent arousals and intra-sleep wakefulness episodes associated with numerous O2 arterial desaturation events, providing evidence of an instability of breathing control.4

A major finding rests with the fact that sleep fragmentation (WASO) observed at altitude proved significantly reduced; further, sleep efficiency (total sleep time/time in bed) significantly increased with either hypnotic compared to placebo, while latency to sleep was shortened in all altitude conditions. The same effects of 10 mg zaleplon and 10 mg zolpidem on sleep have already been demonstrated in previous studies performed in conditions not conducive to sleep, such as noise.24,25 At a simulated altitude of 4,000 meters, we also demonstrated a significantly decreased latency to sleep with zolpidem or zaleplon as well as a trend towards a decreased amount of WASO. Nicholson et al. also reported shortened latency and increased sleep efficiency with low-dose temazepam in the Himalayas providing evidence for a better sleep stability at altitude under hypnotics2.

Unlike zaleplon, zolpidem resulted in a significant increase in SWS at altitude. However, zaleplon is characterized by its very short half-life time (1.1 h) so that positive effects on sleep may be observed early after the intake and may be masked within the whole night. To check this hypothesis, statistical analysis was also run by half-night. The effect of zaleplon on SWS was found significantly positive on the first half of the night but remained less marked than with zolpidem. It is difficult to discuss the beneficial effect of zaleplon and zolpidem on sleep in healthy subjects exposed to high altitude in relation to those of other hypnotics such as benzodiazepines: to our knowledge, no previous study has been performed in real environmental conditions using objective tools for sleep measurement such as polysomnography. However, Dubowitz found a subjective improvement of sleep quality under temazepam at a 5,300-m altitude.7

The issue remains to establish whether the positive effects of either drug on sleep involve alterations in respiratory control or not. Hypnotics drugs such as benzodiazepines may affect ventilation control at moderate altitude26 and depress motor nerve input to upper airway muscles, and therefore cause worsening of sleep related breathing disorders.27 These potentially detrimental effects on respiration require specific attention, because SpO2 is already much reduced at altitude (lowest SpO2 at 3,613 m is between 67%-72%). The number of O2 desaturation events was not decreased under zolpidem or zaleplon, but on the other hand, none of the respiratory parameters were significantly impaired by either drug, confirming that the use of such medication at high altitude is safe, in keeping with previous findings.8,28

Despite positive effects on sleep, cognitive functions were not found to be improved by either hypnotic compared with placebo, except for the attention level in the evening, when the subjects returned from their field assignment. In fact, no cognitive improvement was expected under hypnotic drugs at altitude because most of these cognitive functions were at the same level as in baseline control, which implies that they were not impaired by altitude hypoxia. Indeed, our young, healthy, and well-trained subjects were committed to a classic military assignment and exhibited an increased attention capacity even under placebo. On the other hand, considering the short half-life time of the hypnotics used, no negative residual effect of these medications was expected since they were administered at 21:45 and performance assessment was launched the following morning at 06:00.

AMS was observed in all subjects from the first night of each stay at altitude level because our subjects climbed to an intermediate altitude of 2,400 m using the cable car; subsequently, they trekked easily to the final altitude of 3,600 m given their good training level. A slower ascent might have been accompanied by less AMS. Nevertheless, the fast ascent profile of our protocol magnified the beneficial effects of either hypnotic that was found to alleviate AMS. Because AMS was not decreased with time spent in placebo control conditions, the positive effects of hypnotics on AMS can be attributed to their pharmacological properties and not to a hypothetical process of adjustment to altitude.

In conclusion, zolpidem and zaleplon induced beneficial effects on abnormal sleep architecture observed in trekkers during three nights spent at an altitude of 3,613 meters. Such positive effects on sleep were obtained without any impairment on ventilation. Furthermore, acute mountain sickness was found to be alleviated under either drug. These results suggest that climbers may safely use both drugs. There was no evidence for an improvement of cognitive functions or mood in our young and well-trained militaries at altitude level, despite an improved sleep efficiency index under zaleplon or zolpidem. It would be interesting to perform further studies in less-trained subjects, such as tourists.

Therefore, the important finding of our study resulted in the subsequent claim: zolpidem or zaleplon might alleviate altitude-related sleep disturbances without any detrimental effects on ventilation throughout a period of three days spent at high altitude in real environmental conditions. So, either hypnotic might safely reduce the main complain from climbers at high altitude.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Staff and the trainees of the Military School of High Mountain (EMHM), Chamonix, France, for their helpful assistance. We wish to extend our thanks to Marc Enslen, NESTEC SA, for performing the statistical analysis of the study, and to Frances Ash-Béracochéa for her helpful assistance in reviewing the English writing of the manuscript.

This study was supported by a grant from Sanofi-Aventis Group, Paris, France.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

This study was supported by a grant from Sanofi-Aventis Group, Paris, France. The authors did not receive any income from this company and are all appointed by the French Government and work in governmental institutions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anholm JD, Powles AC, Downey R, 3rd, et al. Operation Everest II: arterial oxygen saturation and sleep at extreme simulated altitude. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:817–26. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.4_Pt_1.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicholson AN, Smith PA, Stone BM, Bradwell AR, Coote JH. Altitude insomnia: studies during an expedition to the Himalayas. Sleep. 1988;11:354–61. doi: 10.1093/sleep/11.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanly PJ, Millar TW, Steljes DG, Baert R, Frais MA, Kryger MH. Respiration and abnormal sleep in patients with congestive heart failure. Chest. 1989;96:480–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khoo MCK, Gottschalk A, Pack A. Sleep-induced periodic breathing and apnea: a theoretical study. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70:2014–24. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.5.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Downey R, Bonnet MH. Performance during frequent sleep disruption. Sleep. 1987;10:354–63. doi: 10.1093/sleep/10.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldenberg F, Richalet J-P, Onnen I, Antezana AM. Sleep apneas and high altitude newcomers. Int J Sports Med. 1992;13(suppl 1):S34–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubowitz G. Effect of temazepam on oxygen saturation and sleep quality at high altitude: randomised placebo controlled crossover trial. BMJ. 1998;316(7131):587–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7131.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaumont M, Goldenberg F, Lejeune D, Marotte H, Harf A, Lofaso F. Effect of zolpidem on sleep and ventilatory patterns at simulated altitude of 4,000 meters. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1864–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.6.8665047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holm KJ, Goa KL. Zolpidem. An update of its pharmacology, therapeutic efficacy and tolerability in the treatment of insomnia. Drugs. 2000;59:865–89. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059040-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh JK, Fry J, Richardson GS, Scharf MB, Vogel GW. Short-term efficacy of zaleplon in older patients with chronic insomnia. Clin Drug Investig. 2000;20:143–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanger DJ, Morel E, Perrault G. Comparison of the pharmacological profiles of the hypnotic drugs zaleplon and zolpidem. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;313:35–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00510-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horne J, Östberg D. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int J Chronobiol. 1976;4:97–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. Washington: US Government Printing Office; 1968. A manual of standardized terminology. Techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reid K, Dawson D. Correlation between wrist activity monitor and electrophysiological measures of sleep in a simulated shiftwork environment for younger and older subjects. Sleep. 1999;22:378–85. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vallières A, Morin C. Actigraphy in the assessment of insomnia. Sleep. 2003;26:902–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.7.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitson D, Stradling J. Autonomic markers of arousal during sleep in patients undergoing investigation for obstructive sleep apnoea, their relationship to EEG arousals, respiratory events and subjective sleepiness. J Sleep Res. 1998;7:53–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1998.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borland RG, Rogers AS, Nicholson AN, Pascoe PA, Spencer MB. Performance overnight in shiftworkers operating a day-night schedule. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1986;57:241–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walters J, Hampton S, Ferns G, Skene D. Effect of menopause on melatonin and alertness rhythms investigated in constant routine conditions. Chronobiol Int. 2005;22:859–82. doi: 10.1080/07420520500263193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicholson AN, Handford ADF, Turner C, Stone BM. Studies on performance and sleepiness with the H-1-antihistamine, desloratadine. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2003;74:809–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee K, Hicks G, Nino-Murcia G. Validity and reliability of a scale to assess fatigue. Psychiatry Res. 1991;36:291–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90027-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bond A, Lader MH. The use of analogue scales in rating subjective feelings. Br J Clin Psychol. 1974;47:211–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burgess K, Johnson P, Edwards N, Cooper J. Acute mountain sickness is associated with sleep desaturation at high altitude. Respirology. 2004;9:485–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2004.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agnew HW, Webb WB, Williams RL. The first night effect: an EEG study of sleep. Psychophysiology. 1966;2:263–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1966.tb02650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parrino L, Terzano M. Arousals and sleep instability. Effects of zolpidem on the cyclic alternating pattern (CAP) In: Freeman H, Puech A, Roth T, editors. Zolpidem: an update on its pharmacological properties and therapeutic place in the management of insomnia. Paris, France: Elsevier; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone BM, Turner C, Mills SM, et al. Noise-induced sleep maintenance insomnia: hypnotic and residual effects of zaleplon. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53:196–202. doi: 10.1046/j.-5251.2001.01520.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Röggla G, Moser B, Röggla M. Effect of temazepam on ventilatory response at moderate altitude. BMJ. 2000;320(7226):56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guilleminault C. Benzodiazepines, breathing and sleep. Am J Med. 1990;88:25s–28s. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90282-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beaumont M, Batéjat D, Coste O, et al. Effects of zolpidem and zaleplon on sleep, respiratory patterns and performance at a simulated altitude of 4,000 m. Neuropsychobiology. 2004;49:154–62. doi: 10.1159/000076723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]