Abstract

Zif268-like zinc fingers are generally regarded as independent DNA-binding modules that each specify three base pairs in adjacent, but discrete, subsites. However, crystallographic evidence suggests that a contact also can occur from the second helical position of one finger to the subsite of the preceding finger. Here we show for the three-finger DNA-binding domain of the protein Zif268, and a panel of variants, that deleting the putative contact from finger 3 can affect the binding specificity for the 5′ base in the adjoining triplet, which forms part of the binding site of finger 2. This finding demonstrates that Zif268-like zinc fingers can specify overlapping 4-bp subsites, and that sequence specificity at the boundary between subsites arises from synergy between adjacent fingers. This has important implications for the design and selection of zinc fingers with novel DNA binding specificities.

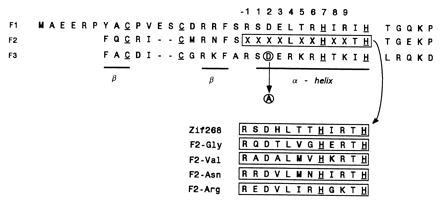

The first cocrystal structure of zinc fingers bound to DNA, that of the mouse transcription factor Zif268 DNA-binding domain, revealed that each of three zinc fingers occupies the major groove, wrapping around the DNA for almost one turn of the double-helix (1). Base specific contacts occur primarily from consecutive turns of the zinc finger α-helices to the guanine-rich strand of the DNA (Fig. 1a). Numbered relative to the first residue in each α-helix (position 1), residues in positions −1, 3, and 6 of each finger, respectively, make contacts with the 3′, middle, and 5′ positions of a 3-bp subsite. Hence, as is shown in Fig. 1a, Zif268 finger 2 may bind nucleotides G7, G6, and T5, whereas the corresponding triplet subsite of finger 3 is G4, C3, and G2. Thus the majority of interactions are with bases on one strand of the DNA, where the 5′-3′ direction runs antiparallel to the N-C direction of the bound protein.

Figure 1.

Interactions between the Zif268 DNA-binding domain and DNA. (a) Schematic diagram of modular recognition between the three zinc fingers of Zif268 and triplet subsites of an optimized DNA binding site, after ref. 2. Straight arrows indicate the stereochemical juxtapositioning of recognition residues with bases of the contacted G-rich DNA strand. Note that because the N-terminal finger contacts the 3′ end of the DNA and the C-terminal finger the 5′ end, binding to the G-rich strand is said to be antiparallel. (b) View of Zif268 finger 3 bound to DNA, showing the possibility of interaction with both DNA strands. Coordinates from ref. 1. (c) The potential hydrogen bonding network between bases on both strands of the DNA and positions −1 (Arg) and 2 (Asp) of finger 3 (1). (d) Schematic diagram of recognition between the three zinc fingers of Zif268 and an optimized DNA binding site including cross-strand interactions. Recognition contacts between Asp2 of each finger and the parallel DNA strand (shown by curly arrows) mean that each finger binds overlapping, 4-bp subsites.

However, the crystal structure also tentatively suggests a hydrogen bonding network at the interface of these subsites, which potentially couples contacts to G4 and T5. In particular, Arg −1 of finger 3 contacts G4, buttressed in this interaction by Asp2 of the same finger, which is in turn positioned to contact A5′—the complementary base to T5 on the parallel strand (Fig. 1 b and c). The H-bonding geometry for the latter interaction is not ideal and was therefore dismissed in the original Zif268 structure (1), but more favorable geometries have since been observed at the interface of subsites for fingers 1 and 2 of Zif268 in the refined structure (2). There is a similar cross-strand interaction in the cocrystal structure of the Drosophila protein Tramtrack with its cognate DNA, where the stereochemistry is favorable (3). Notwithstanding the structural information it was not clear whether the putative contacts from Zif268 to the parallel strand contribute to the specificity of the protein-DNA interaction. If so, this would require a redefinition of the binding subsites for each finger as shown in Fig. 1d.

Biochemical support for this interaction of Asp2 with the parallel DNA strand originated from zinc finger phage display selections (4). Specifically, a zinc finger library based on the DNA binding domain of Zif268 was constructed, in which the middle finger was randomized to generate variants that could bind different triplets. A number of fingers selected from this library were biased toward binding G and/or T at the 5′ position of their cognate triplets irrespective of the residue selected at position 6 (5). This suggested that a conserved residue from a different position was responsible for specificity. It was therefore proposed that the specificity derived from an interaction analogous to that seen in the crystal structures, namely a cross-strand contact from Asp2 in finger 3 to the amino groups at either adenine N6 or cytosine N4, which have similar stereochemistry (6).

To demonstrate that this is indeed the case, we have deleted the potential for the interaction from the third finger of Zif268-like proteins and observed specificity changes in the 5′ position of the middle triplet in the DNA binding site. The result shows that, contrary to the simple picture that zinc fingers of the Zif268-type recognize 3-bp subsites, such fingers can, in fact, specify overlapping, 4-bp subsites. Thus, while such zinc fingers are structurally modular, they are functionally synergistic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site-Directed Mutagenesis of Zif268 and Related Proteins.

Escherichia coli TG1 cells were transfected with fd phage displaying zinc fingers from previous phage selections. Colony PCR was performed with one primer containing a single mismatch to create the Asp to Ala change in finger 3. Cloning of PCR product in phage vector was as described previously (4). Briefly, the forward and backward PCR primers contained unique restriction sites for NotI or SfiI, respectively, and amplified an approximately 300-bp region encompassing three zinc fingers. PCR products were digested with SfiI and NotI to create cohesive ends and were ligated to 100 ng of similarly digested fd-Tet-SN vector. Electrocompetent TG1 cells were transformed with the recombinant vector. Single colonies of transformants were grown overnight in 2× TY (16 g/liter Bactotryptone/10 g liter Bactoyeast extract/5 g/liter NaCl) containing 50 μM ZnCl2 and 15 μg/ml tetracycline. Single-stranded DNA was prepared from phage in the culture supernatant and sequenced with Sequenase 2.0 (United States Biochemical).

Binding Site Signatures.

Procedures were as described previously (5). Briefly, 5′-biotinylated positionally randomized oligonucleotide libraries, containing Zif268 operator variants, were synthesized by primer extension as described. DNA libraries (2 pmol per well) were added to streptavidin-coated ELISA wells (Boehringer Mannheim) in PBS containing 50 μM ZnCl2 (PBS/Zn). Phage solution (overnight bacteria/phage culture supernatant solutions diluted 1:1 in PBS/Zn containing 4% Marvel, 2% Tween, and 20 μg/ml sonicated salmon sperm DNA) were applied to each well (50 μl per well). Binding was allowed to proceed for 1 hr at 20°C. Unbound phage were removed by washing six times with PBS/Zn containing 1% Tween, then washing three times with PBS/Zn. Bound phage were detected by ELISA with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-M13 IgG (Pharmacia Biotech) and quantitated using softmax 2.32 (Molecular Devices).

Determination of Apparent Equilibrium Dissociation Constants (Kd values).

Procedures were as described previously (5). Briefly, appropriate concentrations of 5′-biotinylated DNA binding sites were added to equal volumes of phage solution described above. Binding was allowed to proceed for 1 hr at 20°C. DNA was captured with streptavidin-coated paramagnetic beads (500 μg per well). The beads were washed six times with PBS/Zn containing 1% Tween, then three times with PBS/Zn. Bound phage were detected by ELISA with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-M13 IgG (Pharmacia Biotech) and quantitated using softmax 2.32 (Molecular Devices). Binding data were plotted and analyzed using Kaleidagraph (Abelbeck Software, Reading, PA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Alanine mutagenesis of the Asp2 in finger 3 was carried out on the wild-type Zif268 DNA-binding domain and four related peptides isolated from the phage display library (Fig. 2). The peptides were chosen for this experiment on the basis of the identity of the residue at position 6 of the middle finger. Peptide F2-Arg, which contains Arg at position 6 of finger 2, was chosen because it should specify 5′-G in the middle cognate triplet regardless of the mutation. On the other hand, the peptide F2-Gly with Gly at position 6 would be expected to lose all specificity at the 5′ position of the middle triplet after alanine mutagenesis in finger 3. The other two peptides analyzed, F2-Val and F2-Asn, with Val and Asn at position 6, respectively, were chosen because these particular residues might confer some alternative binding specificity after the constraint imposed by position 2 in finger 3 was removed by alanine mutagenesis (6, 7).

Figure 2.

The amino acid sequences of the three finger constructs used in this study, including wild-type Zif268 and four variants selected from a phage display library in which finger 2 was randomized. Boxed regions indicate the varied regions in each construct. The conserved zinc chelating residues of the zinc fingers are underlined. The aspartate in position 2 of finger 3 and the alanine to which it is mutated in this study are circled.

The DNA binding specificity of each middle finger was assessed before and after the alanine mutation in finger 3 by the binding site signature method (5). This procedure involves screening each zinc finger phage for binding to 12 DNA libraries, each based on the DNA binding site of Zif268 but containing one fixed and two randomized nucleotide positions in the middle triplet. Each of the possible 64 middle triplets is present in a unique combination of three of these positionally randomized libraries; for example, the triplet GAT would be found only in the GNN, NAN, and NNT libraries. Hence the pattern of binding to these reveals the sequence specificity of the middle finger.

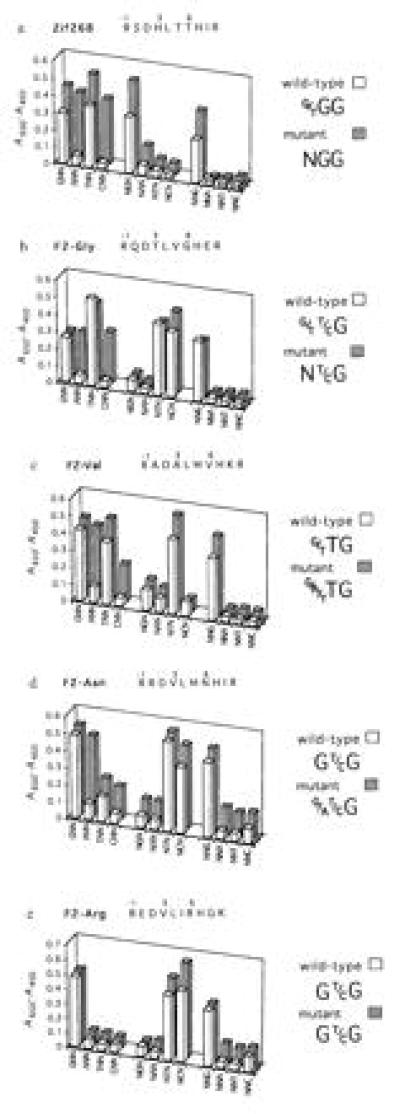

Fig. 3 shows that mutating Asp2 from finger 3 generally alters the pattern of acceptable bases, in the middle triplet, which is conventionally regarded as the binding site for finger 2. As would be expected, according to the hypothesis set out in the introduction, the mutation affects binding at the 5′ position, whereas the specificity at the middle and 3′ position remains unchanged.

Figure 3.

Binding site signatures of the middle finger before and after alanine mutagenesis in position 2 of finger 3. The ELISA signal (A450−A650) showing interaction of zinc finger phage with each positionally randomized DNA library is plotted vertically. From the pattern of binding to these libraries, one or a small number of binding sites can be read off and these are written on the right of the figure. Mutagenesis of position 2 in finger 3 can change the binding specificity for the middle triplet of the Zif268 binding site. In such cases, changes are noted for base 5, but not bases 6 and 7 of the DNA binding site (see Fig. 1a).

The mutation generally leads to a broadening of specificity, for instance in Zif268 where removal of Asp2 in finger 3 results in a protein that is unable to discriminate the 5′ base of the middle triplet (Fig. 3a). However, the expectation that a new 5′ base specificity for the mutants might correlate to the identity of position 6 in finger 2 is not borne out. For example, F2-Gly would be expected to lose sequence discrimination but, although specificity is adversely affected, a slight preference for T is discernible (Fig. 3b). Similarly, F2-Val and F2-Asn, which might have been expected to acquire specificity for one nucleotide, instead have their specificities altered by the mutation (Fig. 3 c and d)—the F2-Val mutant allows G, A, and T, but not C, and the F2-Asn mutant appears to discriminate against both pyrimidines. In the absence of a larger database it is not possible to deduce whether these apparent specificities are the result of amino acid-base contacts from position 6 of finger 2, and if so whether these are general interactions that should be regarded as recognition rules. The apparent discrimination of F2-Gly in particular suggests that this is unlikely to be the case, but rather that in these particular examples other mechanisms are involved in determining sequence bias.

In contrast to the loss of discrimination seen for the other four peptides, F2-Arg continues to specify guanine in the 5′ position of the middle triplet regardless of the mutation in finger 3 (Fig. 3e). In this case, the specificity is derived from the strong interaction between guanine and Arg6 in finger 2. This contact has been observed a number of times in zinc finger cocrystal structures (1, 3, 8) and is the only recognition rule that relates amino acid identity at position 6 to a nucleotide preference at the 5′ position of a cognate triplet (9). This interaction is compatible with, but not dependent on, a contact to the same base pair from Asp2 of the following finger (Fig. 1c). Recognition of this base pair thus can be synergistic, with the specificity potentially deriving from contacts contributed by two adjacent fingers.

This finding explains the restricted sequence specificity of fingers selected from phage display libraries based on Zif268 (5) and also may account for the failure to select zinc finger phage that bind to triplets with a 5′ cytosine or adenine (10, 11). Fig. 3 shows that Asp2 of Zif268 finger 3 specifically excludes adenine and cytosine from the 5′ position of the middle triplet. When this interaction is deleted, one or both of these bases become acceptable, although none of the peptides in this study were capable of specifying either nucleotide using an amino acid from position 6 or any other position in the middle finger. To determine whether this can be achieved, phage selections should be repeated using zinc finger libraries that are purged of the cross-strand contact or libraries of a randomized C-terminal finger.

Regardless of the outcome of these selections, but particularly if it emerges that residues in position 6 cannot directly specify nucleotides other than guanine, it will be essential to define any possible pairings of synergistic contacts that give rise to sequence specificity. Further, it will be of interest to determine whether any amino acids in position 2 can make nonsynergistic contacts to the triplet subsite of a neighboring finger, which by themselves confer sequence specificity to the 5′ position.

Preliminary modeling studies suggest that a number of amino acid residues other than aspartate may be able to make contacts to the parallel DNA strand. For instance, histidine in position 2 might make a cross-strand contact to G or T while maintaining the buttress to Arg −1. Interestingly, phage selections from randomized C-terminal finger libraries have yielded several fingers with His2, and Leu or Ser at position 1, which also may influence the binding specificity (12). The crystal structures of zinc finger-DNA complexes show that Ser2 is also capable of an analogous contact to the parallel DNA strand (8, 13). Because serine is present in about 60% of all zinc fingers (14) and can act as a donor or acceptor of a hydrogen bond, it would be surprising if this amino acid at position 2 was generally capable of contributing to the binding specificity. Rather, this contact probably stabilizes the protein-DNA complex and will be a useful device in the design of zinc finger proteins with high affinity for DNA (Y.C. and A.K., unpublished work). It also should be noted that Ser at position 2 has been observed in the Tramtrack structure to contact the 3′ base of a triplet in the antiparallel DNA strand, although this requires a deformation of the DNA (3).

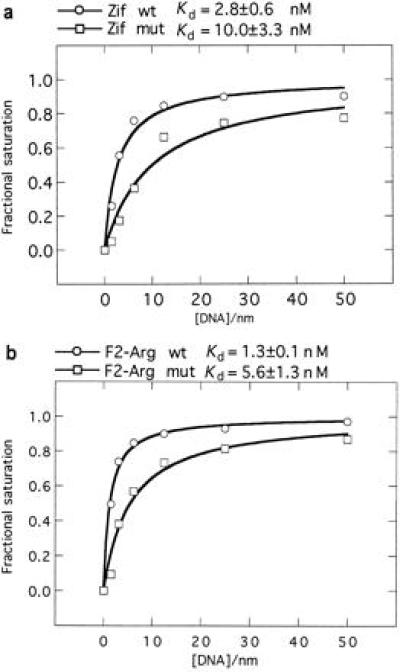

To determine the contribution of Asp2 in finger 3 to the binding strength, apparent equilibrium dissociation constants were determined for Zif268 and F2-Arg before and after the Ala mutation (Fig. 4). Both mutants show approximately a 4-fold reduction in affinity for their respective binding sites under the conditions used. The reduction was likely a direct result of abolishing cross-strand contacts from Asp2, rather than a consequence of changes in binding specificity at the 5′ position of the middle triplet, because the mutant Zif268 loses all specificity whereas F2-Arg registers no change in specificity. However, note that two stabilizing interactions are abolished: an intramolecular buttressing interaction with Arg −1 on finger 3 and the intermolecular contact with the secondary DNA strand. An independent comparison of wild-type Zif268 binding to its consensus binding site flanked by G/T or A/C also found a 5-fold reduction in affinity for those sites that are unable to satisfy a contact from Asp2 to the secondary DNA strand (15). While the effects of perturbations in the DNA structure cannot be discounted in this case, the results of both experiments would seem to suggest that the reduction in binding affinity results from loss of the protein-DNA contact. Nevertheless, the intramolecular contact between positions −1 and 2 in a zinc finger is a further level of synergy that may have to be taken into account before the full picture emerges, describing the possible networks of contacts that occur at the protein-DNA interface in the region of the overlapping subsites.

Figure 4.

Apparent equilibrium binding curves showing the effect of replacing Asp2 in finger 3 by Ala for (a) Zif268 DNA-binding domain (consensus binding site used: 5′-GCG TGG GCG-3′); and (b) F2-Arg construct (consensus binding site used: 5′-GCG GTG GCG-3′). wt, wild-type constructs; mut, mutant constructs.

CONCLUSION

Zinc fingers have the potential to specify overlapping, 4-bp subsites, such that the specificity at the subsite interface is mediated by two different residue positions from adjacent fingers.

The inter-finger synergism observed for Zif268-like zinc fingers has a parallel in the mode of binding of the DNA-binding domain from c-Myb, which contains two tandem modules each with a three-helix bundle structure (16). A comparison of the structures of c-Myb and Zif268 bound to DNA shows a similarity in the geometry of interaction between the recognition helices from the respective proteins and the major groove of DNA. However, the helices of c-Myb are much closer together and interact extensively with each other, leading to a 2-bp overlap between the binding sites of each domain. Adjacent zinc fingers are more widely spaced, but, nevertheless, the recognition helices are close enough to specify subsites that overlap by 1 bp as has been shown in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Fairall for critical comments on this manuscript and M. Moore for help with molecular modeling. This work was funded by the Medical Research Council.

ABBREVIATION

- F2

finger 2

References

- 1.Pavletich N P, Pabo C O. Science. 1991;252:809–817. doi: 10.1126/science.2028256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elrod-Erickson M, Rould M A, Nekludova L, Pabo C O. Structure. 1996;4:1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fairall L, Schwabe J W R, Chapman L, Finch J T, Rhodes D. Nature (London) 1993;366:483–487. doi: 10.1038/366483a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choo Y, Klug A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11163–11167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choo Y, Klug A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11168–11172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seeman N D, Rosenberg J M, Rich A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:804–808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.3.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki M. Structure. 1994;2:317–326. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim C, Berg J M. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:940–945. doi: 10.1038/nsb1196-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choo Y, Klug A. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rebar E J, Pabo C O. Science. 1994;263:671–673. doi: 10.1126/science.8303274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jamieson A C, Kim S-H, Wells J A. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5689–5695. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greisman H A, Pabo C O. Science. 1997;275:657–661. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pavletich N P, Pabo C O. Science. 1993;261:1701–1707. doi: 10.1126/science.8378770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs G. Ph.D. thesis. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smirnoff A H, Milbrandt J. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2275–2287. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogata K, Morikawa S, Nakamura H, Sekikawa A, Inoue T, Kanai H, Sarai A, Ishii S, Nishimura Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6428–6432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]