Abstract

Aims

To assess parental understanding and memorisation of the information given when seeking for consent to their child's participation to clinical research, and to identify the factors of significant influence on parents' decision making process.

Methods

Sixty eight parents who had been approached for enrolling their child in a clinical oncology or HIV study were asked to complete an interview. Their understanding was measured by a score which included items required to obtain a valid consent according to French legislation.

Results

Items that were best understood by parents were the aims of the study (75%), the risks (70%), the potential benefits to their child (83%), the potential benefits to other children (70%), the right to withdraw (73%), and voluntariness (84%). Items that were least understood were the procedures (44%), the possibility of alternative treatments (53%), and the duration of participation (39%). Less than 10% of the parents had understood all these points. Ten parents (15%) did not remember that they had signed up for a research protocol. Thirty three parents (48%) reported no difficulty in making their decision. Twenty four parents (38%) declared that they made their decision together with the investigator; 26 (41%) let the physician decide. Fifty four parents (78%) felt that the level of information given was satisfactory.

Conclusion

There was an apparent discrepancy between parents' evaluation of the adequacy of the information delivered and evaluation of their understanding and memorisation. The majority of parents preferred that the physician take as much responsibility as possible in the decision making process.

Keywords: informed consent, pediatric clinical trial, parents' understanding, parents' decision making process

There is still an overwhelming need to test safety and efficacy of curative and preventive therapies in paediatric populations. Results from studies in adults do not provide sufficient or appropriate information and cannot be extrapolated to children. For many years, children have been “therapeutic orphans” and have been denied the benefits of clinical research.1,2,3,4 Recently, the need for research involving children has been recognised, and action has been taken at the federal level in the USA to address both the need for paediatric research and the protection of the welfare and rights of children as research subjects.5

Informed consent is a cornerstone of efforts to protect human subjects from research risks. Many questions persist regarding its application in the context of paediatrics. At the most fundamental level is an existential question: “Can informed consent exist for paediatric research?”. For adults, the informed consent process represents an exchange of information between doctor and patient. This process is more complicated in paediatric trials as a third party is involved. The geometry of paediatric ethics is best understood as a triangle with the child on the top and the parent(s) and clinician‐investigator at the base to act as support. In addition to this difference, paediatric ethics requires that the best interests of the child take precedence over the concept of autonomy. In other words, the question of who decides, so important in adult ethics, is less important in paediatric ethics than the question of what decision is best for the child?

It is imperative that parents are given sufficient information to make an informed choice in decision making. Although it is every investigator's goal to satisfy the sample size requirements of their study in the shortest period of time, recruitment practices must ensure that all eligible subjects are fully informed and that their individual rights to self‐determination or the rights of their surrogate to protect are preserved.6

Unfortunately, little is known about the understanding of the parents and the process by which they make the decisions to enrol their child in a clinical trial. Much of the research in the area of informed consent has attended to a single aspect of informed consent: the informed consent form approved by the National Consultative Bioethics Committee.7

Our objective was to assess how parents who had (or had not) given informed consent for their children to participate in an HIV or oncology clinical trial, evaluated the information delivered, understood and remembered this information, and made their decision.

Methods

The study population included parents (or guardians) who had been approached to allow their child to participate in clinical trials between January 2002 and May 2003. The study was conducted in three hospitals in France where children were treated for either a cancer or an HIV infection: Curie Institute (Paris), Necker Enfants Malades Hospital (Paris), and Timone Hospital (Marseille).

Regardless of whether the parents had consented or not to allow their child to participate in a clinical trial, the parents were invited by their referent doctor to complete an interview. Parents who agreed to participate were interviewed by a paediatrician trained in clinical research and ethical aspects of clinical research, either during the child's inpatient admission in the paediatric hospital or in the outpatient clinic. This latter choice was made in order to both minimise parents' travel and maximise participation. The interviewer was the same paediatrician during the whole study and was involved neither in the care of the child nor in the clinical trial performed in the three hospitals. At the beginning of the interview, parents were informed that their answers would be kept confidential and would not affect the care of their child in any way. The interview was audiotaped with parents' agreement. The interviewer was allowed to clarify questions and prompt the parents for additional information, but did not offer any specific information on the studies.

The interview was organised in a semi‐structured manner and conducted into two parts: understanding and memorisation of the informed consent, and factors influencing parents' choice.

At the beginning of the interview, parents were asked about the clarity (“yes” or “no”) and completeness of the information they received from the investigator (“I would like to get your impression on how well you think the clinical research study was explained to you. How did you find the sum of information provided: adequate, too much, not enough?” and about their knowledge concerning legislation for clinical trials).

The interview was designed to determine the parents' understanding of nine items required by French and European legislation to be included in the informed consent document (study purpose, methodology of the protocol, risks, direct and indirect potential benefits, the right to withdraw, duration of participation, possibility of alternative treatments, voluntariness).8,9,10 The parents' levels of understanding of these individual items were scored for each item after the interview comparing the written transcription of the interview to the informed consent forms. Scores of 1 or 0 were assigned for each item based on whether the parents had a complete (1) or incomplete (0) understanding of these items. A global score was calculated, ranging from 0 to 9, which was the sum of the scores for each item).

The items and the corresponding questions during the interview were as follows:

Study purpose (What was the purpose of the study?)

Protocol design and procedures (What have the investigators done to your child for this study?)

Risks (What were the possible risks or discomforts associated with the study?)

Direct benefits (Describe the possible benefits to your child as a result of this research)

Indirect benefits (Describe the possible benefits to other children as a result of this research)

The right to withdraw (Could you change your mind about the study and stop the protocol once you had agreed to allow your child to participate?)

Duration of participation (What was the approximate length of time that your child was involved in the study?) This item was scored 1 if the difference between the interview and the protocol was less than 30% of the exact response

Alternative treatments or procedures (If you did not allow your child to participate in the study, was an alternative treatment possible?)

Voluntariness (Was your child's participation in the study based on voluntariness?).

Parents' recollection of their decision making process was explored using the following questions:

“Was your decision difficult to make?”

“Who made the decision of whether your child entered the clinical study or not?”. “Did your child participate to the decision making process?”

“What was most important in order to make your decision?”

“Regarding the relationship with the doctor asking for your consent, what was the critical issue?”.

The following items were also recorded: type of disease (cancer or HIV), type of clinical trial (interventional or observational), time elapsed between consent and date of the interview, child's age, geographic origin, people interviewed (father or mother or guardian), and the child's and parents' previous experience as a research subject.

Statistical analyses were performed using NCSS. Descriptive statistics were calculated for sociodemographic details and parents' answers. Comparisons of quantitative data were performed using unpaired t test. Logistic regression analysis was used to correlate parents' understanding and expected influencing factors. Data were expressed as percentages, mean (SD). Significance was accepted at the 5% level (p < 0.05).

Results

Seventy one parents whose child's participation had been sought for a clinical trial for either a malignant disease (n = 42) or an HIV infection (n = 29) were approached for interview. Of these, 68 (96%) agreed to be interviewed: 63 (89%) had consented to allow their child to participate in the clinical trial (consenters), and 5 (7%) had declined their child's participation (non‐consenters). Of the three parents who did not accept to be interviewed, two alleged their lack of time as the reason for no participation and one did not remember being approached for a study.

The majority of the parents were European (n = 59, 87%); others were African (n = 7, 10%) or Asian (n = 2, 3%). The interview was performed with the mother (n = 43, 63%), the father (n = 8, 12%), both the mother and the father (n = 15, 22%), or the legal guardian (n = 2, 3%). Fifty five parents (81%) were in two‐parent homes, whereas 13 (19%) were single‐parents. The duration of the interview was 27.3 (13.4) minutes and ranged between 10 and 75 minutes. The age of the children at the time of the interview ranged from 4.5 to 18 years (8.9 (5.36) years). Consent had been sought between 21 days and 2 years before the date of the interview (14.0 (10.4) months). Thirteen of the children (19%) had been enrolled in an observational study and 55 (81%) in an interventional one, including 3 (4.4%) in a phase I, 14 (20.6%) in a phase II, 14 (20.6%) in a phase III (randomised clinical trial), and 24 (35.3%) in a phase IV (post‐marketing) study (with blood sampling).

Understanding and memorisation

Ten parents (15%) did not remember that they had signed up for a research protocol.

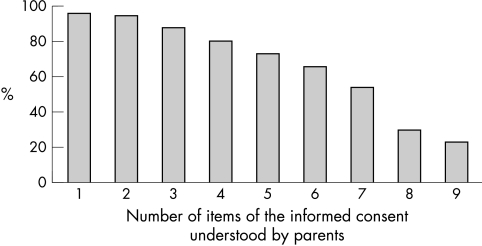

Sixty four parents (94%) understood at least one of the nine items (fig 1) and 15 parents (21%) had full understanding of all the items required by the legislation to be included in the informed consent document.

Figure 1 Cumulative number of items of the informed consent understood by parents.

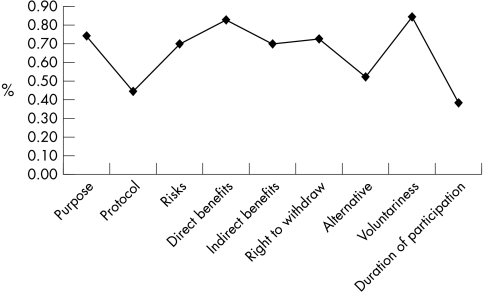

Items that were best understood were the aims (n = 51, 75%), the risks (n = 47, 70%), the potential benefits to their child (n = 56, 83%), the potential benefits to other children (n = 47, 70%), their right to withdraw (n = 49, 73%), and voluntariness (n = 57, 84%). Items that were least understood were the procedures (n = 30, 44%), the possibility of alternative treatments (n = 36, 53%) and the duration of participation (n = 27, 39%) (fig 2).

Figure 2 Items of the informed consent understood by parents.

Several factors were found to be significantly associated with better understanding. They included parents' impression of clearness of the pointed out information (5.1 (2.6) v 6.5 (2.2); p = 0.03); the type of study (interventional more than observational ones; 6.3 (2.5) v 4.2 (2.6); p = 0.01); and the absence of reported difficulty in the decision making process (7.0 (1.8) v 5.9 (2.5); p = 0.05). There was a trend for a better understanding when informed consent was sought some time after the diagnosis was made rather than at the same time (6.5 (2.3) v 5.4 (2.8); p = 0.07).

Understanding and memorisation was not influenced by the geographic origin, the type of disease, whether or not the child had a previous experience as a research participant, and the age of the child.

The time elapsed between the study proposal to the parents and the interview for the present study was not related to the understanding and memorisation.

Fifty four parents (78%) thought that the level of information given was adequate, 11 (16%) that they were given too much information, and only 3 (6%) that they were not informed enough. Fifty parents (74%) felt that the information was clear. Fifty six parents (83%) declared they had never received information concerning the legislation for clinical trials before their child was sick. These three factors were not shown to be related to the parents' levels of understanding

Parents' decision making process

Thirty three parents (48%) reported no difficulty in making their decision. Several factors were found to be significantly associated with the difficulty for the parent to consent to their child's participation in a research study. These included the feeling of unclearness of the information provided (χ2 = 6.47; p = 0.01), poor understanding (χ2 = 3.54; p = 0.05), consent sought at time of diagnosis (χ2 = 24.9; p < 0.0001), type of disease (cancer) (χ2 = 21.3; p < 0.0001), and poor confidence in their physician (χ2 = 4.46; p = 0.03).

In only 9 cases (14%) did parents declare that they had made the final decision of participation of their child to the clinical trial on their own. Twenty four parents (38%) declared that they had made the decision together with the investigator, and 26 (41%) let the physician decide for them. In one case (2%), the parents declared that the child had taken the final decision. Thirty four parents (50%) said that their child participated in the decision. The most frequent reasons were: “because he (she) is primarily involved” (n = 12, 18%), and “for better acceptance of his (her) illness” (n = 7, 10%). The other parents said that their child did not participate and their most frequent reasons alleged were: “it's too hard for him (her)” (n = 20, 30%), and “he (she) doesn't know his (her) real diagnosis” (n = 5, 7%).

In the present study, parents reported that they chose to enrol their child in a study for a variety of reasons. The most frequent reasons were the hope that their child would receive the most advanced treatments available (n = 26, 38%), and also the confidence they placed in the medical team (n = 13, 19%). Twenty parents (29%) felt obliged to participate because they thought there was no available therapeutic alternative.

The main requirement the parents spontaneously had about the investigator who sought for their consent was confidence on him (her) (n = 47, 69%), and the main expectation from him (her) was the listening to parents (n = 5, 8%).

We did not find any influence on the decision making process of the geographic origin, of whether or not the child had a previous experience as a research participant, and the age of the child.

Discussion

Our results showed that strict adherence to informed consent procedures does not guarantee full comprehension of basic items included in the informed consent forms.

Although there are some available data on the understanding of information provided when seeking for consent from adult subjects, there are few data regarding the understanding of the parents acting as proxies for the enrolment of their children in research. In a study performed by paediatric anaesthesiologists,11 70%, 57%, and 53% of parents had full understanding of risks, benefits to their child, and procedures, respectively. In our study, 70%, 83%, and 44% of parents had full understanding of these items. In another study, Van Stuijvenberg and colleagues12 showed that only 45% of parents approached for permission to enrol their child in a randomised, placebo controlled trial of ibuprofen syrup to prevent recurrent febrile seizures were aware of five of six major trial characteristics (study aim, right to withdraw, risks, randomisation, reasons for signing up, chances of placebo). This difference may have to do with the severity and or chronicity of the disease. Snowdon and colleagues13 showed that parents of neonates enrolled in a randomised trial had poor understanding of the nature of the trial, and many had no perception that randomisation would occur.

There was an apparent discrepancy between parents' feeling of adequacy of the information provided and the evaluation of their understanding. It may be possible that parents understand enough about the research to make an informed decision, in line with their perceptions, but could still be judged deficient in their knowledge according to the legal criteria. Tait and colleagues14 have evidenced that parents prioritised items/issues for seeking consent differently than investigators: parents ranked the risks and potential benefits to their child as the two most important items they needed to understand before making a decision regarding their child's participation in a research study for paediatric anaesthesiology. In our study, the possibility of receiving the most advanced available treatments appeared to be the first motivation for the parents to give their consent. When interpreting these results, we must take into account that they were based on relatively high risk diseases. As such, they may not be able to be generalised to studies involving low risk benefit profiles. However, these findings show that informed consent does not adequately serve as a universal model for parental permission.

Before the final quarter of the 20th century, traditional medical ethics had been based on a model that assumed beneficent paternalism. The concept of autonomy and the ideal of patients' control on medical decisions gained prominence in the latter part of the century, and has been more widely embraced in America than in other countries. The rise of autonomy has now completely transformed expectations and medical practice, and informed consent has been used as the mean for performing this change. Rather than patients trusting doctors to make good decisions on their behalf, the new model requires that patients become active participants in medical decisions. This concept is more difficult to apply to paediatric clinical trials. As the majority of the parents do not want to share the decision making with the children, the investigator could be faced with a dilemma: a conflict between “respect for autonomy” of the parents who do not want to share the decision with the child and respect for autonomy of the children as requested by European and US legislation.

What is already known on this topic

Much of the research in the area of informed consent has attended to a single aspect of informed consent: the informed consent form approved by the National Consultative Bioethics Committee

Little is known about the understanding of the parents and the process by which they make the decisions to enrol their child in a clinical trial

Increasing efforts must be accomplished to improve the informed consent process in order to accommodate not only the moral principle of autonomy, but also the competing moral principles of beneficence, non‐maleficience, and justice.15 A better balance between these principles may in fact be more conversant with the societal mandate, which allows the exposure of some members of society to calculated risks as research subjects in exchange for the real or potential benefits of medical progress to the community as a whole. Because consent without understanding has ethical and legal implications, investigators must make every effort to enhance understanding, so the rights of the research subject are protected to ensure that parents have sufficient information and understanding to formulate a preference for participation. Perceived clarity of the information by the parents, type of study, and time lag between diagnosis and interview for informed consent may influence understanding.11 During the first few days after the diagnosis of a life threatening disease is made, parents are very shocked and anxious; the time lag was often very limited and their ability to take a decision decreased.16,17,18,19

In conclusion, European and US regulations require that disclosure to prospective research participants includes items such as the risks and benefits of the research, available alternatives to study participation, and the fact that participants have the right to withdraw from the trial at any time. A discrepancy could exist between the understanding by the parents of the informed consent and their level of satisfaction concerning the quality of information received during the informed consent process. Trust and quality of the relationship between parents and investigators appear to be the main values required by the parents before giving their consent. A written, signed and dated informed consent form reviewed by several Institutional Review Boards and independent committees is not sufficient to be sure that the decision of parents to give their consent is based on objective knowledge. A limitation of this study is that parents have been drawn from a single European country. It could be interesting to compare these results with the results obtained in the USA as the principle of autonomy has been more widely embraced in American medicine than in other countries.

What this study adds

A written, signed and dated informed consent form reviewed by several Institutional Review Boards and independent committees is not sufficient to be sure that the decision of parents to give their consent is based on objective knowledge

Trust and quality of the relationship between parents and investigators appear to be the main values required by the parents before giving their consent

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the parents who agreed to participate and thereby made this work possible.

Footnotes

Funding: this work was supported in part by the “Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale”, laboratory “Sanofi‐Synthelabo”, and INSERM (CRES)

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Dahlquist G. Pediatric research is necessary. The children must be guaranteed with a complete protection. Lakartidningen 20041012238–2239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen G. Therapeutic orphans, pediatric victims? The Best Pharmaceuticals for Child Act and existing pediatric human subject protection. Food Drug Law J 200358661–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wendler D, Forster H. Why we need legal standards for pediatric research. J Pediatr 2004144150–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shevell M I. Ethics of clinical research in children. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2002946–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Pediatric Exclusivity Provision January 2001. Status Report to Congress. http://www.fda.gov/cder/pediatric/reportcong01.pdf:8‐18

- 6.Gill D, Crawley F P, LoGiudice M.et al Ethics Working Group of the Confederation of European Specialists in Pediatrics. Guidelines for informed consent in biomedical research involving paediatric populations as research participants. Eur J Pediatr 2003162455–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paasche‐Orlow M K, Taylor H A, Brancati F L. Readability standards for informed‐consent forms as compared with actual readability. N Engl J Med 2003348721–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Loi Huriet‐Serusclat (loi n° 88‐1138 du 20.12.1988, J.O. du 22.12.1988, loi n° 94‐630 du 25.07.1994, J.O. du 26.07.1994, loi n° 98‐535 du 1er juillet 1998, JO du 2 juillet 1998, ordonnance n° 2000‐548 du 15 juin 2000, JO du 22 juin 2000)

- 9. Procédure de codécision: deuxième lecture (A5‐0349/2000). Résolution législative du Parlement européen relative à la position commune du Conseil en vue de l'adoption de la directive du Parlement européen et du Conseil concernant le rapprochement des dispositions législatives, réglementaires et administratives des Etats membres relatives à l'application de bonnes pratiques cliniques dans la conduite d'essais cliniques de médicaments à usage humain (8878/1/2000‐C5‐0424/2000‐1997/0197(COD)). http://www3.europarl.eu.int/omk

- 10. Loi du 4 mars 2002 relative aux droits des malades et à l'amélioration du système de santé. (Loi n° 2002‐303 du 04 mars 2002, JO du 05 mars 2002)

- 11.Tait A R, Voepel‐Lewis T, Malviya S. Do they understand? (Part I) Parental consent for children participating in clinical anesthesia and surgery research. Anesthesiology 200398603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Stuijvenberg M, Suur M H, de Vos S.et al Informed consent, parental awareness, and reasons for participating in a randomised controlled study. Arch Dis Child 199879120–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snowdon C, Garcia J, Elbourne D. Making sense of randomization; responses of parents of critically ill babies to random allocation of treatment in a clinical trial. Soc Sci Med 1997451337–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tait A R, Voepel‐Lewis T, Robinson A.et al Priorities for disclosure of the elements of informed consent for research: a comparison between parents and investigators. Paediatric Anaesthesia 200212332–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beauchamp T L, Childress J F.Principles of biomedical ethics, 5th edn. New York: Oxford University Press 2001

- 16.Simon C, Eder M, Raiz P.et al Informed consent for pediatric leukemia research: clinician perspectives. Cancer 200192691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dahlquist L M, Czyzewski D I, Copeland K G.et al Parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer: anxiety, coping, and marital distress. J Pediatr Psychol 199318365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grossman S A, Paintadosi S, Covahey C. Are informed consent forms that describe clinical oncology research protocols readable by most patients and their families? J Clin Oncol 1996122211–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamprill J. Every‐day ethics: paediatric clinical trials. Spead‐read 1, 2. 2001. http://www.speadread.com